A Review of Food-Related Social Media and Its Relationship to Body Image and Disordered Eating

Abstract

1. Introduction

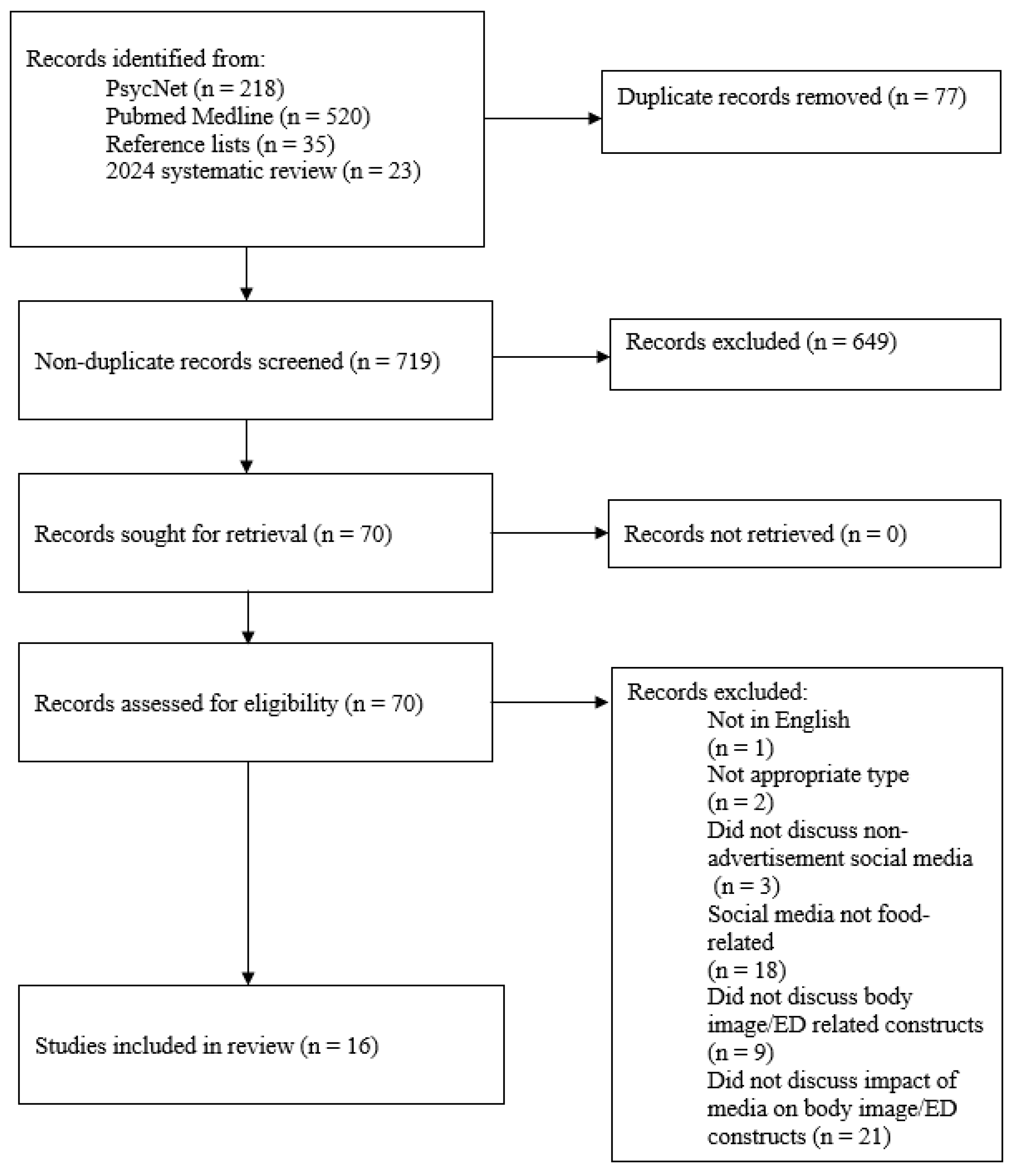

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Studies

3.2. Correlational Studies

3.3. Quasi-Experimental Studies

| Author, Year (Country) | Study Design | Participant Characteristics | Media Type | Outcome(s) | Overall Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bissonnette-Maheux et al., 2015 [26] (Canada) | Qualitative | n= 33; mean age = 44; 100% female; 100% white; 30% family income between $20,000–$49,999 | Healthy eating blogs, written by registered dietician | NA | Two of six groups discussed guilt about eating habits after having read the blogs. |

| Strand and Gustafsson, 2020 [20] (Sweden) | Qualitative | n = 1316 social media comments | Mukbang videos | NA | A total of 150 out of 1316 (11.4%) comments discussed increased dietary restriction; 75/1316 (5.7%) discussed overeating. |

| von Ash et al., 2023 [27] (USA) | Correlational | n = 264; mean age = 33.7; 49% female; 40% white | Mukbang videos (viewing frequency, time spent viewing, mukbang addiction) | Body dissatisfaction; shape/weight overevaluation; dietary restraint | Viewing frequency (β = 0.11, f2 = 0.02), time spent viewing (β = −2.05, f2 = 0.02) and addiction (β = −1.28, f2 = 0.08) related to body dissatisfaction. Viewing frequency (β = −0.33) and addiction (βs ≥ 0.28, 0.03 ≤ f2 ≥ 0.13) related to various binging and/or purging symptoms; time spent viewing related to overevaluation of shape and weight (β = 2.77, f2 = 0.06). Correlations between other variables not significant. |

| Kircaburun et al., 2021 [28] (Turkey) | Correlational | n = 140; mean age = 21.7; 66% female | Mukbang videos | Disordered eating symptomology | Mukbang addiction related to more symptoms of disordered eating (β = 0.43, r = 0.24, p < 0.01). |

| Jeong et al., 2024 [30] (South Korea) | Quasi-experimental | n = 50,455; 100% adolescents; 49% female; generally middle class | Mukbang and cookbang videos | Eating behaviors; body shape perception; body image distortion | Boys viewing mukbangs each day tended to believe their bodies were smaller, while girls tended to believe bodies were larger. More boys found to have body image distortion at higher mukbang viewing frequencies. |

| Wu et al., 2022 [29] (Australia) | Correlational | n = 269; mean age = 20.7; 100% women; 84.8% white | Clean eating content on Instagram | Compulsive exercise; athletic-ideal internalization; thin-ideal internalization; drive for thinness; disordered eating symptomology; body dissatisfaction | Posting related to compulsive exercise (rs ≥ 0.24) and athletic ideal internalization (rs ≥ 0.24), but not thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness, or bulimia nervosa symptoms (rs ≤ 0.10). Viewing related to all outcomes (rs ≥ 0.13). |

| Allen et al., 2018 [33] (Australia) | Quasi-experimental | n = 762; median age = 27; 100% female; 87% white | Clean eating blogs | Dietary restraint | Individuals following guidance of blogs reported higher dietary restraint than individuals who did not (F(2729) = 26.93; p ≤ 0.01). |

| Al-Bisher and Al-Otaibi, 2022 [34] (Saudi Arabia) | Quasi-Experimental | n = 1092; mean age = 23; 100% female | Nutrition information on various social media sites | Eating concerns | Those who: spent 30–60 min searching for nutrition content on social media (OR = 1.09; p = ≤ 0.05) preferred to learn about nutrition through dieticians on social media (OR = 1.17; p ≤ 0.001) or were more interested in social media related to dieting/dietary supplements (OR = 0.87; p < 0.001) and had a higher likelihood of eating concerns. |

| Abu Alwafa and Badrasawi, 2023 [35] (Palestine) | Quasi-Experimental | n = 905; mean age = 20; 100% female | Nutrition advice from model and celebrity social media accounts | Body appreciation | Body appreciation negatively related to taking the food-related guidance on celebrity social media channels (ES = 0.23, p = 0.01). |

| Caner et al., 2022 [32] (Turkey) | Quasi-Experimental | n = 1363; mean age = 15.9; 63.8% girls; 63.4% perceived “normal” family income | Nutrition/diet content on influencer accounts | Emotional eating | Following these influencers was related to more emotional eating and social appearance anxiety than following other types of influencers (Kruskal–Wallis H Test value ≤ 10.66, ps ≤ 0.03). |

| Tazeoglu and Kuyulu Bozdogan, 2022 [31] (Turkey) | Quasi-Experimental | n = 1160; mean age = 21.8; 52.2% female | Food videos | Eating-related guilt | More women (72.8%) than men (38.9%) said that they feel guilty about eating something directly following watching a video (p = 0.01). |

| Kinkel-Ram et al., 2022 [36] (USA) | Experimental | Sample 1: n = 222; mean age = 18.9; 100% women; 85.9% white. Sample 2: n = 214; mean age = 19.3; 100% female; 71.1% white | Photos of low-calorie food | Body image; intent for disordered eating | Viewing low-calorie food photos promoted more intention for disordered eating than viewing travel photos amongst women in midwestern US sample: F(1217) = 323.37, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.03). Neither sample demonstrated differences in body image across the two conditions (ps > 0.15). |

| Zeeni et al., 2024 [37] (Lebanon) | Experimental | n = 63; mean age = 22; 68.3% female | “Junk” food Instagram photos | Food craving | Browsing photos on Instagram resulted in greater food craving for salty, savoury, and fatty foods (ts ≥ 2.93, ps ≤ 0.005, 0.47 ≥ ds ≤ 0.70) than browsing control accounts. No differences in body image (t = 1.38, p = 0.17, d = 0.18) or cravings for sweet foods (t =2.0, p = 0.052, d = 0.29). |

| Fiuza and Rodgers, 2023 [38] (USA) | Experimental | n = 421; mean age = 19.5; 100% women | Diet culture-related TikTok videos (for or against diet culture) | Weight/shape satisfaction; intuitive eating; body appreciation; restriction; exercise urges | Diet video condition promoted lower weight and shape satisfaction compared to condition against diet culture (F(2, 392) = 5.05, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.03). Condition against diet culture promoted more body appreciation compared to neutral video condition (F(2, 393) = 3.09, p = 0.05, partial η2 = 0.02). Video against diet culture promoted more intuitive eating compared to the neutral video condition (F(2, 392) = 4.29, p = 0.01, partial η2 = 0.02). No significant differences amongst conditions for restriction or exercise urge scores. |

| Drivas et al., 2024 [39] (USA) | Experimental | n = 316; mean age = 19.8; 62.7% women; 75.6% white | “What I Eat in a Day” videos | Body appreciation; body satisfaction; diet intentions | Video type (i.e., viewing higher calorie days) indirectly and positively impacted body appreciation and diet intentions, indirectly negatively impacted body dissatisfaction. |

| Neter et al., 2018 [40] (Israel) | Experimental | n = 165; mean age = 25.7; 84.8% female | Food porn featured in a travel vlog | Food cravings | Those who viewed vlogs with food porn did not report different levels of craving than those who watched travel vlogs without food porn (F(1162) = 0.77; p = 0.38). |

3.4. Experimental Studies

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodin, J.; Siberstein, L.; Striegel-Moore, R. Women and weight: A normative discontent. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1984, 32, 267–307. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, D.A.; Jafary, A.M.; Gruys, K.; Daniels, E.A. Surveys and the Epidemiology of Body Image Dissatisfaction. In Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance; Cash, T.F., Ed.; Elsevier Science & Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 766–774. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, L.; Fallon, E.A.; Redding, C.A. Prevalence of body dissatisfaction among United States adults: Review and recommendations for future research. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brechan, I.; Kvalem, I.L. Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eat. Behav. 2015, 17, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawijit, Y.; Likhitsuwan, W.; Ludington, J.; Pisitsungkagarn, K. Looks can be deceiving: Body image dissatisfaction relates to social anxiety through fear of negative evaluation. IJAMH Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2019, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prnjak, K.; Hay, P.; Mond, J.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Lonergan, A.; Mitchison, D. The distinct role of body image aspects in predicting eating disorder onset in adolescents after one year. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2021, 130, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Altabe, M.; Tantleff-Dunn, S. Exacting Beauty: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment of Body Image Disturbance; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Saipoo, A.N.; Vahedi, Z. A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, J.V.; Mills, J.S. The effects of active social media engagement with peers on body image in young women. Body Image 2019, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markey, C.H.; August, K.J.; Gillen, M.M.; Rosenbaum, D.L. An examination of youths’ social media use and body image: Considering TikTok, Snapchat, and Instagram. J. Media Psychol. Theor. Methods Appl. 2024; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe-Calverley, E.; Grieve, R. Do the metrics matter? An experimental investigation of Instagram influencer effects no mood and body dissatisfaction. Body Image 2021, 36, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaznavi, J.; Taylor, L.D. Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of #thinspiration images on popular social media. Body Image 2015, 14, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Boepple, L.; Thompson, J.K. A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 49, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignard, N.A.L.; Jarry, J.L. The “Little Red Riding Hood Effect:” Fitspiration is just as bad as thinspiration for women’s body satisfaction. Body Image 2021, 36, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladwig, G.; Tanck, J.A.; Quittkat, H.L.; Vocks, S. Risks and benefits of social media trends: The influence of “fitspiration”, “body positivity”, and text-based “body neutrality” on body dissatisfaction and affect in women with and without eating disorders. Body Image 2024, 50, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prichard, I.; Kavanagh, E.; Mulgrew, K.E.; Lim, M.S.C.; Tiggemann, M. The effect of Instagram #fitspiration images on young women’s mood, body image, and exercise behaviour. Body Image 2020, 33, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis, A.; Carrà, G.; Calogero, R.; Fida, R.; Clerici, M.; Zanetti, M.A.; Riva, G. The developmental effects of media-ideal internalization and self-objectification processes on adolescents negative body-feelings, dietary restraint, and binge eating. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 25, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.; Thornton, L.; De Choudhury, M.; Teevan, J.; Bulik, C.M.; Levinson, C.A.; Zerwas, S. Facebook use and disordered eating in college-aged women. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, S.; Castle, D.; Cunningham, M.; Murray, S.B.; Bastian, B.; Barlow, F.K. How does exposure to thinspiration and fitspiration relate to symptom severity among individuals with eating disorders? Evaluation of a proposed model. Body Image 2018, 27, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, M.; Gustafsson, S.A. Mukbang and disordered eating: A netnographic analysis of online eating broadcasts. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2020, 44, 586–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versace, F.; Frank, D.W.; Stevens, E.M.; Deweese, M.M.; Guindani, M.; Schembre, S.M. The reality of “food porn”: Larger brain responses to food-related cues than to erotic images predict cue-induced eating. Psychophysiol 2018, 56, e13309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejova, Y.; Abbar, S.; Haddadi, H. Fetishizing food in digital age: #foodporn around the world. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Cologne, Germany, 17–20 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carrote, E.R.; Vella, A.M.; Lim, M.C.S. Predictors of “liking” three types of health and fitness-related content on social media: A cross-sectional study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.V. Interactive effects of Instagram foodies’ hastagged #foodporn and peer users’ eating disorder on eating intention, envy, parasocial interaction, and online friendships. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. Index 2018, 21, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Kemps, E.; Prichard, I. Digging into digital buffets: A systematic review of eating-related social media content and its relationship with body image and eating behaviours. Body Image 2024, 48, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissonnette-Maheux, V.; Provencher, V.; Lapointe, A.; Dugrenier, M.; Dumas, A.A.; Pluye, P.; Straus, S.; Gagnon, M.P.; Desroches, S. Exploring women’s beliefs and perceptions about healthy eating blogs: A qualitative study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Ash, T.; Huynh, R.; Deng, C.; White, M.A. Associations between mukbang viewing and disordered eating behaviors. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 56, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircaburun, K.; Yurdagul, C.; Kuss, D.; Emirtekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Problematic mukbang watching and its relationship to disordered eating and internet addiction: A pilot study among emerging adult mukbang watchers. Int. J. Ment. Health 2021, 19, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Harford, J.; Petersen, J.; Prichard, I. “Eat clean, train mean, get lean”: Body image and health behaviours of women who engage with fitspiration and clean eating imagery on Instagram. Body Image 2022, 42, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Lee, E.; Han, G. Association between mukbang and cookbang viewing and body image perception and BMI in adolescents. JHPN J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazeoglu, A.; Kuyulu Bozdogan, F.B. The effect of watching food videos on social media on increased appetite and food consumption. Nutr. Clin. Diet. Hosp. 2022, 42, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Caner, N.; Sezer Efe, Y.; Başdaş, Ö. The contribution of social media addiction to adolescent LIFE: Social appearance anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 8424–8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.; Dickinson, K.M.; Prichard, I. The dirt on clean eating: A cross sectional analysis of dietary intake, restrained eating and opinions about clean eating among women. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bisher, M.M.; Al-Otaibi, H.H. Eating concerns associated with nutritional information obtained from social media among Saudi young females: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Alwafa, R.; Badrasawi, M. Factors associated with positive body image among Palestinian university female students, cross-sectional study. Health Psychol. Behav. 2023, 11, 2278289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinkel-Ram, S.S.; Staples, C.; Rancourt, D.; Smith, A.R. Food for thought: Examining the relationship between low calorie density foods in Instagram feeds and disordered eating symptoms among undergraduate women. Eat. Behav. 2022, 47, 101679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeni, N.; Abi Kharma, J.; Malli, D.; Khoury-Malhame, M.; Mattar, L. Exposure to Instagram junk food content negatively impacts mood and cravings in young adults: A randomized controlled trial. Appetite 2024, 195, 107209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiuza, A.; Rodgers, R.F. The effects of brief diet and anti-diet social media videos on body image and eating concerns among young women. Eat. Behav. 2023, 51, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drivas, M.; Simone Reed, O.; Berndt-Goke, M. #WhatIEatInADay: The effects of viewing food diary TikTok videos on young adults’ body image and intent to diet. Body Image 2024, 49, 101712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neter, E. The Effect of Exposure to Food in Social Networks on Food Cravings and External Eating. Doctoral Dissertation, Astar Tavor-Ruppin Academic Centre, Emek Hefer, Israel, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison process. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seekis, V.; Bradley, G.L.; Duffy, A.L. Appearance-related social networking sites and body image in young women: Testing an objectification-social comparison model. PWQ Psychol. Women Q. 2020, 44, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Want, S.C.; Botres, A.; Vahedi, Z.; Middleton, J.A. On the cognitive (in)efficiency of social comparisons with media images. Sex Roles 2015, 73, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roorda, B.A.; Cassin, S.E. A Review of Food-Related Social Media and Its Relationship to Body Image and Disordered Eating. Nutrients 2025, 17, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020342

Roorda BA, Cassin SE. A Review of Food-Related Social Media and Its Relationship to Body Image and Disordered Eating. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020342

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoorda, Bethany A., and Stephanie E. Cassin. 2025. "A Review of Food-Related Social Media and Its Relationship to Body Image and Disordered Eating" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020342

APA StyleRoorda, B. A., & Cassin, S. E. (2025). A Review of Food-Related Social Media and Its Relationship to Body Image and Disordered Eating. Nutrients, 17(2), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020342