Cross-Sectional Study on the Influence of Religion on the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food in Spanish Schoolchildren in North Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Subjects

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Blood Pressure

2.4. Dietary Intake

2.5. Anthropometric Measurements

2.6. Other Variables

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Physical Characteristics of Participating Students

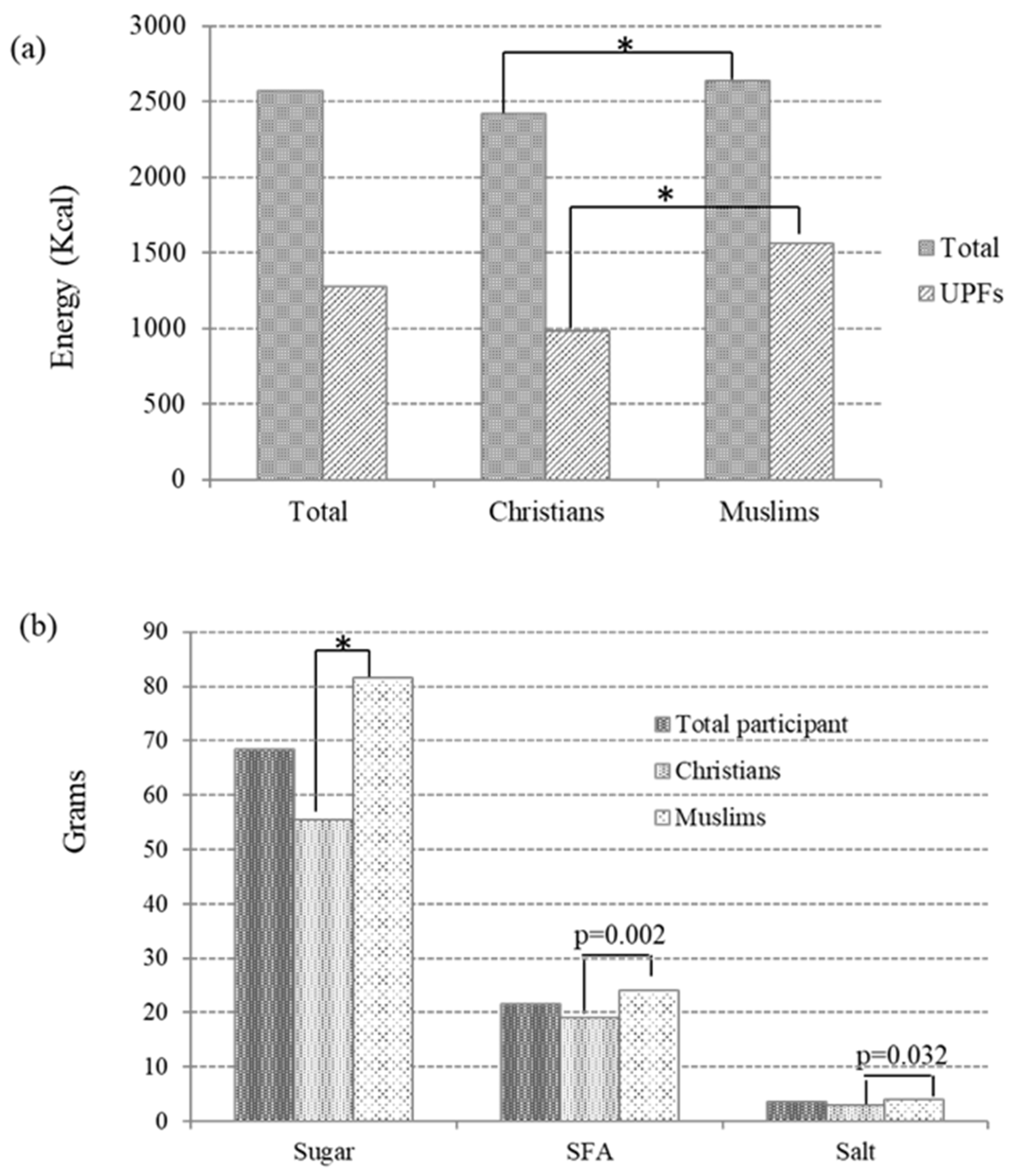

3.2. Schoolchildren Consuming Ultra-Processed Food (UPF) According to Sex and Religious Group

3.3. Data on Energy and Key Nutrients Derived from the Ingestion of Ultra-Processed Food (UPF)

3.4. Frequency of Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food (UPF) Among Christian and Muslim Schoolchildren

3.5. Influence of Religious Groups on the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food (UPF)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, A. Is the world converging to a ‘Western diet’? Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangelosi, G.; Palomares, S.M.; Pantanetti, P.; De Luca, A.; Biondini, F.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Mancin, S.; Sguanci, M.; Petrelli, F. COVID-19, Nutrients and Lifestyle Eating Behaviors: A Narrative Review. Diseases 2024, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebreiro, C.; Aballay, L.R.; Ponce, S.; Niclis, C. Hábitos de consumo y actividad física en adolescentes durante el aislamiento por COVID-19. Rev. Salud Pública 2023, 28, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejeda-Manzanera, J.; Rodrigo-Vega, M. Hábitos de alimentación y calidad de dieta en estudiantes universitarios de magisterio en relación a su adherencia a la dieta mediterránea. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2021, 95, e1–e14. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.; Tschirley, D.; Liverpool-Tasie, L.S.O.; Awokuse, T.; Fanzo, J.; Minten, B.; Vos, R.; Dolislager, M.; Sauer, C.; Dhar, R.; et al. The processed food revolution in African food systems and the double burden of malnutrition. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 28, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, L.G.; Martinez Steele, E.; Canella, D.S.; Monteiro, C.A. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and associated sociodemographic factors in the USA between 2007 and 2012: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdán, E.; Romero, M.C. Conocimientos y consumo de bebidas azucaradas en estudiantes del nivel secundario de un establecimiento educativo de Argentina. Rev. Española Nutr. Comunitaria 2020, 26, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.; Machado, P.; Santos, T.; Sievert, K.; Backholer, K.; Hadjikakou, M.; Russell, C.; Huse, O.; Bell, C.; Scrinis, G.; et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez, C.; Escalante, A.; Huerta, J.; Villarreal, M.E. Efectos de la frecuencia de consumo de alimentos ultraprocesados y su asociación con los indicadores del estado nutricional de una población económicamente activa en México. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2021, 48, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, M.; Costabile, G.; Testa, R.; D’Abbronzo, G.; Nettore, I.C.; Macchia, P.E.; Giacco, R. Ultra-Processed Foods and Human Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Prado, S.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; Montero-Alonso, M.Á.; Perona, J.S.; González-Jiménez, E. Assessing the Impact of Religion and College Life on Consumption Patterns of Ultra-Processed Foods by Young Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Jacoby, E. Public Health Nutrition special issue on ultra-processed foods. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, S.; Buoncristiano, M.; Gelius, P.; Abu-Omar, K.; Pattison, M.; Hyska, J.; Duleva, V.; Musić Milanović, S.; Zamrazilová, H.; Hejgaard, T.; et al. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep Duration of Children Aged 6–9 Years in 25 Countries: An Analysis within the WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI) 2015–2017. Obes. Facts 2021, 14, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN). Estudio ENE-COVID: Situación Ponderal de la Población Infantil y Adolescente en España; Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición—Ministerio de Consumo: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calero Bernal, M.L.; Varela Aguilar, J.M. Diabetes tipo 2 infantojuvenil. Rev. Clínica Española 2018, 218, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo Ramos, J.J. Educación para la salud. Nutrición y gastronomía en las ciudades autónomas de Melilla y Ceuta. Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Diego Cordero, R.; Guerrero Rodríguez, M. La influencia de la religiosidad en la salud: El caso de los hábitos saludables/no saludables. Cult. los Cuid. Rev. Enfermería Humanidades 2018, 22, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STROBE. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Declaración de Helsinki. Available online: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracion-de-helsinki-de-la-amm-principios-eticos-para-las-investigaciones-medicas-en-seres-humanos/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Pickering, T.G.; Hall, J.E.; Appel, L.J.; Falkner, B.E.; Graves, J.; Hill, M.N.; Jones, D.W.; Kurtz, T.; Sheps, S.G.; Roccella, E.J. Recommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement in Humans and Experimental Animals. Circulation 2005, 111, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos Suarez, V.; Rubio Mañas, J.; Sanchidrián Fernández, R.; Robledo de Dios, T. Spanish National dietary survey on children and adolescents. EFSA Support. Publ. 2015, 12, 900E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.M.; Elbusto-Cabello, A.; Alberdi-Albeniz, M.; De la Presa-Donado, A.; Gómez-Pérez de Mendiola, F.; Portillo-Baquedano, M.P.; Churruca-Ortega, I. New pre-coded food record form validation. Rev. Española Nutr. Humana Dietética 2014, 18, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfell-Jones, M.; Olds, T.; Stewart, A. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment; ISAK: Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco-Parra, C.L.; Domínguez-Espinosa, A.D.C. Diseño y validación de la Escala de Actitud Religiosa. Rev. Psicol. 2014, 23, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Health Organization Healthy Diet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017.

- Lane, M.M.; Gamage, E.; Du, S.; Ashtree, D.N.; McGuinness, A.J.; Gauci, S.; Baker, P.; Lawrence, M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Srour, B.; et al. Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ 2024, 384, e077310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Mokhtari, O.; Anzid, K.; Hilali, A.; Cherkaoui, M.; Mora-Urda, A.I.; Montero-López, M.d.P.; Levy-Desroches, S. Impact of migration on dietary patterns and adherence to the Mediterranean diet among Northern Moroccan migrant adolescents in Madrid (Spain). Med. J. Nutrition Metab. 2020, 13, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, J.; Sundar Budhathoki, S.; Niraula, S.R.; Pandey, S.; Thakur, N.; Pokharel, P.K. Prehypertension and its predictors among older adolescents: A cross-sectional study from eastern Nepal. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0001117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, D.S.; Kabir, Z.; Revathi Devi, K.; Peter, P.S.; Das, B.C. Gender differences in central obesity: Implications for cardiometabolic health in South Asians. Indian Heart J. 2020, 72, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli, E.; Schochat, T.; Korzets, Z.; Tekesmanova, D.; Bernheim, J.; Golan, E. Prehypertension and Obesity in AdolescentsA Population Study. Am. J. Hypertens. 2006, 19, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Jeong, S.I.; Kim, S.H. Obesity and hypertension in children and adolescents. Clin. Hypertens. 2024, 30, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nyaga, U.F. Cardiovascular disease prevention should start in early life. BMC Glob. Public Health 2023, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, S.; Kumari, C. Impact of junk food on adolescent body image and well-being. Int. J. Home Sci. 2024, 10, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S. Association of Unhealthy Food Practices with Nutritional Status of Adolescents. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2021, 33, 25766–25778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reales-Moreno, M.; Tonini, P.; Escorihuela, R.M.; Solanas, M.; Fernández-Barrés, S.; Romaguera, D.; Contreras-Rodríguez, O. Ultra-Processed Foods and Drinks Consumption Is Associated with Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Española de Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutrición (AESAN). Estrategia NAOS. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/web/nutricion/seccion/estrategia_naos.htm (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Sandri, E.; Sguanci, M.; Cantín Larumbe, E.; Cerdá Olmedo, G.; Werner, L.U.; Piredda, M.; Mancin, S. Plant-Based Diets versus the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Their Socio-Demographic Determinants in the Spanish Population: Influence on Health and Lifestyle Habits. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero Ferreiro, C.; Cancelas Navia, P.; Lora Pablos, D.; Gómez de la Cámara, A. Geographical and Temporal Variability of Ultra-Processed Food Consumption in the Spanish Population: Findings from the DRECE Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valizadeh, P.; Wen Ng, S. Promoting Healthier Purchases: Ultraprocessed Food Taxes and Minimally Processed Foods Subsidies for the Low Income. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar. PLAN de Colaboración para la Mejora de la Composición de los Alimentos y Bebidas y Otras Medidas 2017–2020. Available online: https://www.aesan.gob.es/AECOSAN/docs/documentos/nutricion/DOSSIER_PLAN_2017_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Osei-Kwasi, H.; Mohindra, A.; Booth, A.; Laar, A.; Wanjohi, M.; Graham, F.; Pradeilles, R.; Cohen, E.; Holdsworth, M. Factors influencing dietary behaviours in urban food environments in Africa: A systematic mapping review. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 2584–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Trenholm, J.; Rahman, A.; Pervin, J.; Ekström, E.-C.; Rahman, S. Sociocultural Influences on Dietary Practices and Physical Activity Behaviors of Rural Adolescents—A Qualitative Exploration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Males (n = 233) | Females (n = 357) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 590) | Christians (n = 86) | Muslims (n = 147) | Christians (n = 106) | Muslims (n = 251) | ||

| Age (years) | 15.65 ± 0.73 | 15.88 ± 0.72 | 15.67 ± 0.76 * | 15.63 ± 0.69 | 15.56 ± 0.72 | |

| Height (cm) | 166.74 ± 9.33 | 174.31 ± 7.60 | 175.07 ± 7.07 | 161.20 ± 6.78 | 161.60 ± 6.09 | |

| Weight (kg) | 63.18 ± 14.13 | 70.89 ± 16.98 | 67.01 ± 15.44 | 59.69 ± 10.78 | 59.77 ± 11.77 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.72 ± 4.65 | 23.75 ± 6.47 * | 21.77 ± 4.40 | 22.93 ± 3.99 | 22.83 ± 4.23 | |

| Nutritional status: | ||||||

| Low weight | 82 (13.9) | 8 (9.3) | 36 (24.5) * | 7 (6.6) | 31 (12.4) | |

| Normal weight | 347 (58.8) | 51 (59.3) | 75 (51.0) | 69 (65.1) | 152 (60.6) | |

| Overweight | 117 (19.8) | 17 (19.8) * | 28 (19.0) | 24 (22.6) | 48 (19.1) | |

| Obesity | 44 (7.5) | 10 (11.6) * | 8 (5.4) | 6 (5.7) | 20 (8.0) | |

| WC (cm) | 74.24 ± 10.62 | 79.28 ± 11.27 | 75.43 ± 10.46 | 71.77 ± 8.99 | 72.87 ± 10.50 | |

| HC (cm) | 98.25 ± 35.40 | 107.46 ± 8.38 * | 95.40 ± 10.93 | 96.51 ± 10.55 | 97.49 ± 12.00 | |

| WHR | 0.771 ± 0.130 | 0.80 ± 0.11 | 0.79 ± 0.9 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 076 ± 0.15 | |

| Waist-to-height ratio | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.06 | |

| Fat Mass (Kg) | 14.58 ± 9.03 | 12.26 ± 9.60 | 9.96 ± 8.10 | 17.12 ± 10.04 | 17.01 ± 7.54 | |

| Lean Mass (Kg) | 48.54 ± 9.95 | 58.65 ± 9.20 | 56.53 ± 8.75 | 43.13 ± 5.24 | 42.67 ± 5.34 | |

| Muscle Mass (Kg) | 46.56 ± 16.02 | 55.00 ± 9.67 | 53.74 ± 8.31 | 40.94 ± 4.98 | 41.84 ± 20.76 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 114.97 ± 15.74 | 124.20 ± 18.84 | 119.02 ± 15.98 | 115.73 ± 13.15 | 109.12 ± 12.95 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 70.67 ± 10.45 | 72.71 ± 10.72 | 70.26 ± 11.22 | 71.98 ± 10.66 | 69.66 ± 9.70 | |

| MBP | 92.82 ± 11.06 | 98.46 ± 12.13 | 94.64 ± 11.30 | 93.86 ± 9.92 | 89.39 ± 9.86 | |

| Blood pressure classification: | ||||||

| Normal | 537 (91.0) | 67 (34.4) | 128 (65.5) | 103 (30.1) | 239 (69.9) * | |

| Prehypertensive | 36 (6.1) | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | 0 | 10 (100) * | |

| Hypertensive | 17 (2.9) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 3 (60.0) | 2 (40) | |

| Males (n = 233) | Females (n = 357) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 590) | Christians (n = 86) | Muslims (n = 147) | Christians (n = 86) | Muslims (n = 147) | |

| Industrial juices | 214 (36.3) | 20 (23.3) | 64 (43.5) ** | 22 (20.8) | 108 (43.0) ** |

| Sweetened beverages | 149 (25.3) | 21 (24.4) | 42 (28.6) | 14 (13.2) | 72 (28.7) ** |

| Milkshakes | 147 (24.9) | 12 (14.0) | 40 (27.2) ** | 13 (12.3) | 82 (32.8) ** |

| Industrial pastries | 147 (24.9) | 16 (18.6) | 41 (27.9) | 14 (13.2) | 76 (30.3) ** |

| Sweets | 143 (24.2) | 11 (12.8) | 26 (17.7) | 18 (17.0) | 88 (35.1) ** |

| Chocolate | 149 (25.3) | 16 (18.6) | 39 (26.7) | 14 (13.2) | 80 (31.9) ** |

| Potato chips (bag) | 77 (13.1) | 8 (9.3) | 16 (10.9) | 7 (6.6) | 46 (18.3) ** |

| Salty snacks | 87 (14.7) | 4 (4.7) | 21 (14.3) * | 8 (7.5) | 46 (18.3) ** |

| Industrial sauces | 188 (31.9) | 20 (23.3) | 59 (40.1) * | 18 (17.0) | 91 (36.4) ** |

| Sausages (fresh or cooked) | 35 (5.9) | 3 (3.5) | 7 (4.8) | 7 (6.6) | 18 (7.2) |

| Sausages | 111 (18.8) | 24 (27.9) ** | 20 (13.7) | 26 (24.5) * | 41 (16.3) |

| Hamburgers | 54 (9.2) | 5 (5.8) | 12 (8.2) | 11 (10.4) | 26 (10.4) |

| All (n = 590) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 590) | Christians (n = 192) | Muslims (n = 398) | |

| Industrial juices | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 5 (4) ** |

| Sweetened beverages | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | 4 (4) * |

| Milkshakes | 4 (4) | 3 (4) | 5 (4) ** |

| Industrial pastries | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) ** |

| Sweets | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) ** |

| Chocolate | 4 (4) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) ** |

| Potato chips (bag) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) ** |

| Salty snacks | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 5 (2) ** |

| Industrial sauces | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) ** |

| Sausages (fresh or cooked) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Sausages | 4 (3) | 4 (3) | 3 (4) * |

| Hamburgers | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) |

| Ultra-Processed Products | n | % | OR | 95% IC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial juices | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 376 | 63.7 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 214 | 36.3 | 2.700 ** | 1.830–4.037 | |

| Sugared beverages | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 441 | 74.7 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 149 | 25.3 | 1.824 * | 1.76–2.757 | |

| Milkshakes | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 442 | 75.0 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 147 | 25.0 | 2.925 ** | 1.850–4.748 | |

| Industrial pastries | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 443 | 75.1 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 147 | 24.9 | 2.217 ** | 1.440–3.510 | |

| Sweets | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 447 | 75.8 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 143 | 24.2 | 2.197 ** | 1.437–3.541 | |

| Chocolate | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 440 | 74.7 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 149 | 25.3 | 2.272 ** | 1.482–3.606 | |

| Potato chips (bag) | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 513 | 86.9 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 77 | 13.1 | 2.176 * | 0.630–2.140 | |

| Salty snacks | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 503 | 85.3 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 87 | 14.7 | 3.431 ** | 1.844–6.579 | |

| Industrial sauces | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 401 | 68.1 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 188 | 31.9 | 2.508 ** | 1.635–3.704 | |

| Sausages (fresh or cooked) | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 555 | 94.1 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 35 | 5.9 | 1.184 | 0.574–2.594 | |

| Sausages | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 479 | 81.2 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 111 | 18.8 | 0.511 | 1.071–1.530 | |

| Hamburgers | |||||

| Low consumption < 1 | 536 | 90.8 | 1 | ||

| High consumption > 1 | 54 | 9.2 | 1.117 | 0.630–2.140 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohatar-Barba, M.; González-Jiménez, E.; López-Olivares, M.; Fernández-Aparicio, Á.; Schmidt-RioValle, J.; Enrique-Mirón, C. Cross-Sectional Study on the Influence of Religion on the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food in Spanish Schoolchildren in North Africa. Nutrients 2025, 17, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020251

Mohatar-Barba M, González-Jiménez E, López-Olivares M, Fernández-Aparicio Á, Schmidt-RioValle J, Enrique-Mirón C. Cross-Sectional Study on the Influence of Religion on the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food in Spanish Schoolchildren in North Africa. Nutrients. 2025; 17(2):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020251

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohatar-Barba, Miriam, Emilio González-Jiménez, María López-Olivares, Ángel Fernández-Aparicio, Jacqueline Schmidt-RioValle, and Carmen Enrique-Mirón. 2025. "Cross-Sectional Study on the Influence of Religion on the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food in Spanish Schoolchildren in North Africa" Nutrients 17, no. 2: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020251

APA StyleMohatar-Barba, M., González-Jiménez, E., López-Olivares, M., Fernández-Aparicio, Á., Schmidt-RioValle, J., & Enrique-Mirón, C. (2025). Cross-Sectional Study on the Influence of Religion on the Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food in Spanish Schoolchildren in North Africa. Nutrients, 17(2), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17020251