Healthy Diets Are Associated with Weight Control in Middle-Aged Japanese

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Metrics

2.3. Data Analysis

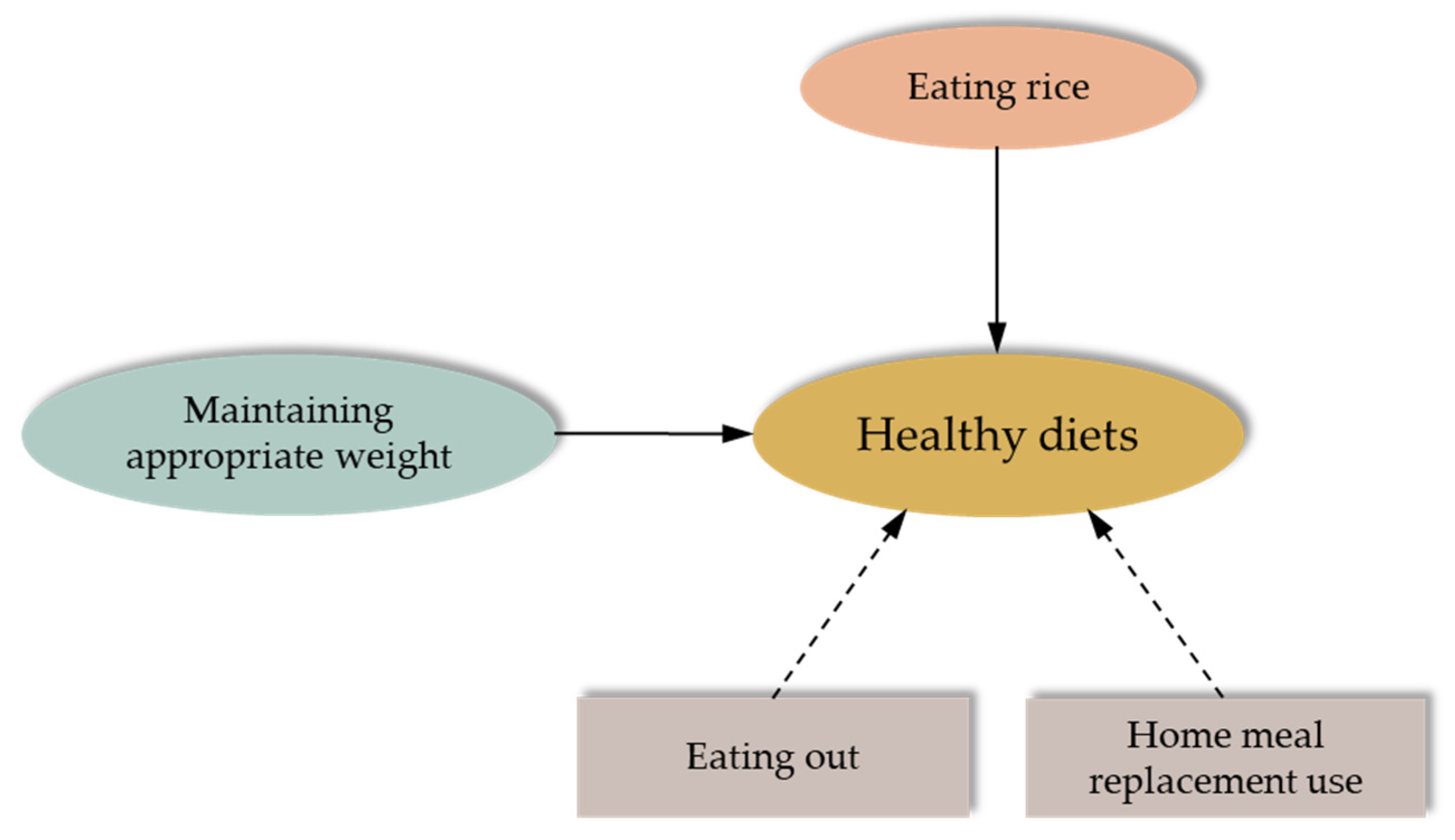

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCD | non-communicable disease |

| BMI | body mass index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| GFI | goodness-of-fit index |

| AGFI | adjusted goodness-of-fit index |

| CFI | comparative fit index |

| RMSEA | root mean square error of approximation |

| AIC | Akaike’s information criterion |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- GBD. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okunogbe, A.; Nugent, R.; Spencer, G.; Powis, J.; Ralston, J.; Wilding, J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: Current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Kibayashi, E.; Nakade, M. Dietary salt restriction practices contribute to obesity prevention in middle-aged and older Japanese adults. Nutrients 2025, 17, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, K.; Takemi, Y.; Eto, K.; Iwama, N. Association of vegetable intake with dietary behaviors, attitudes, knowledge, and social support among the middle-aged Japanese population. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 2018, 65, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, S.; Nagata, C.; Nakamura, K.; Fujii, K.; Kawachi, T.; Takatsuka, N.; Shimizu, H. Diet based on the Japanese food Guide spinning top and subsequent mortality among men and women in a General Japanese population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurotani, K.; Akter, S.; Kashino, I.; Goto, A.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Sasazuki, S.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S.; Japan Public Health Center based Prospective Study Group. Quality of diet and mortality among Japanese men and women: Japan public health center based prospective study. BMJ 2016, 352, i1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiike, N.; Hayashi, F.; Takemi, Y.; Mizoguchi, K.; Seino, F. A new food Guide in Japan: The Japanese food Guide spinning top. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Ministry of Agriculture. Forestry and Fisheries; The Fourth Basic Program for Shokuiku Promotion (Provisional Translation). 2021. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syokuiku/attach/pdf/kannrennhou-30.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Mekary, R.A.; Giovannucci, E.; Cahill, L.; Willett, W.C.; van Dam, R.M.; Hu, F.B. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in older women: Breakfast consumption and eating frequency. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, M.; Yatsuya, H.; Hilawe, E.H.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Chiang, C.; Otsuka, R.; Toyoshima, H.; Tamakoshi, K.; Aoyama, A. Breakfast skipping is positively associated with incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: Evidence from the Aichi Workers’ Cohort Study. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 25, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, H.; Gan, Y.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Tong, X.; Lu, Z. Breakfast skipping and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3013–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Iso, H.; Sawada, N.; Tsugane, S.; JPHC Study Group. Association of breakfast intake with incident stroke and coronary heart disease: The Japan Public Health Center–Based Study. Stroke 2016, 47, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, A.R.; Powles, J.W. Fruit and vegetables, and cardiovascular disease: A review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainio, H.; Weiderpass, E. Fruit and vegetables in cancer prevention. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 54, 111–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batres-Marquez, S.P.; Jensen, H.H.; Upton, J. Rice consumption in the United States: Recent evidence from food consumption surveys. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horikawa, H.; Akamatsu, R.; Taniguchi, T. Relationships between Rice Consumption, Dietary Habits, and Health among Adults according to Age. Eiyougakuzashi 2011, 69, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibayashi, E.; Nakade, M.; Morooka, A. Dietary habits and health awareness in regular eaters of well-balanced breakfasts (consisting of shushoku, shusai, and Fukusai). Eiyougakuzashi 2020, 78, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2015. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/h27-houkoku.html (accessed on 5 August 2025). (In Japanese)

- Overcash, F.; Reicks, M. Diet quality and eating practices among Hispanic/Latino men and women: NHANES 2011–2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyōgo Prefectural Government. The Hyogo Diet Survey. 2016. Available online: https://web.pref.hyogo.lg.jp/kf17/kf17/28shokuseikatu-jittaichousa.html (accessed on 5 August 2025). (In Japanese)

- Statistics Bureau of Japan. Population Census of Japan. 2015. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/index.html (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan. 2016. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/h28-houkoku.html (accessed on 5 August 2025). (In Japanese)

- Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare; Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. Ethical Guidelines for Life Sciences and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2021. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/001077424.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025). (In Japanese)

- Kibayashi, E.; Nakade, M.; Morooka, A. Association of a Healthy Dietary Habit with Dietary Attitudes for Lifestyle Disease Prevention and with Health Behavior. Eiyougakuzashi 2022, 80, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, H. Covariance Structure Analysis Structural Equation Modeling, Amos ed.; Tokyo Tosho Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2007. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.O.; Chun, O.K.; Obayashi, S.; Cho, S.; Chung, C.E. Is consumption of breakfast associated with body mass index in US adults? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 1373–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; McNaughton, S.A.; Cleland, V.J.; Crawford, D.; Ball, K. Health, behavioral, cognitive, and social correlates of breakfast skipping among women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods. J. Nutr 2013, 143, 1774–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines; Japan. 2000. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/japan/en/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Sanjyonishi, S. Sanetaka Koki, Bottom of Vol. 5; Takahashi, R., Ed.; Zokugunshoruiju-kanseikai, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1963. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamashina, T. Tokikuni Kyoki, No. 4: Shiryo Sanshu; Toyoda, T., Itakura, H., Eds.; Zokugunshoruiju-kanseikai, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 1977. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, H. Tairyo-Ko Nikki, No. 4: Shiryo Sanshu; Bunko, S., Nagayama, N., Eds.; Yagi-Shoten, Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2012. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Najjar, R.S.; Feresin, R.G. Plant-based diets in the reduction of body fat: Physiological effects and biochemical insights. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tackling NCDs: ‘Best Buys’ and Other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259232 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

| Items | Interval Scale | Score (Points) |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy diets | ||

| Having a well-balanced meal at least twice daily | ||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 4 | |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 3 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 2 | |

| 1 day/week or fewer | 1 | |

| Eating breakfast regularly | ||

| 6 or 7 days/week | 4 | |

| 4 or 5 days/week | 3 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 2 | |

| 1 day/week or fewer | 1 | |

| Number of vegetable dishes daily | ||

| 5 dishes or more | 5 | |

| 4 dishes | 4 | |

| 3 dishes | 3 | |

| 2 dishes | 2 | |

| 1 dish or fewer | 1 | |

| Maintaining appropriate weight | ||

| Control of energy intake | ||

| Daily | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 3 | |

| Not very often | 2 | |

| Never | 1 | |

| Restriction of salt intake | ||

| Daily | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 3 | |

| Not very often | 2 | |

| Never | 1 | |

| Control of fat intake | ||

| Daily | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 3 | |

| Not very often | 2 | |

| Never | 1 | |

| Control of sugar intake | ||

| Daily | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 3 | |

| Not very often | 2 | |

| Never | 1 | |

| Use of nutritional fact labels | ||

| Always | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 3 | |

| Not very often | 2 | |

| Rarely | 1 | |

| Regular exercise | ||

| Always | 4 | |

| Sometimes | 3 | |

| Used to, but not currently | 2 | |

| Never | 1 | |

| Other items that potentially relate to healthy diets | ||

| Frequency of eating rice | ||

| Breakfast | 7 days/week | 5 |

| 5 or 6 days/week | 4 | |

| 3 or 4 days/week | 3 | |

| 1 or 2 days/week | 2 | |

| 0 days/week | 1 | |

| Lunch | 7 days/week | 5 |

| 5 or 6 days/week | 4 | |

| 3 or 4 days/week | 3 | |

| 1 or 2 days/week | 2 | |

| 0 days/week | 1 | |

| Dinner | 7 days/week | 5 |

| 5 or 6 days/week | 4 | |

| 3 or 4 days/week | 3 | |

| 1 or 2 days/week | 2 | |

| 0 days/week | 1 | |

| Eating out frequency | ||

| At least twice daily | 7 | |

| Once daily | 6 | |

| 4 to 6 days/week | 5 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 4 | |

| 1 day/week | 3 | |

| 1–3 days/month | 2 | |

| Not at all | 1 | |

| Frequency of home meal replacement (ready-to-eat food) use | ||

| At least twice daily | 7 | |

| Once daily | 6 | |

| 4 to 6 days/week | 5 | |

| 2 or 3 days/week | 4 | |

| 1 day/week | 3 | |

| 1–3 days/month | 2 | |

| Not at all | 1 |

| Characteristics | Total | Men | Women | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 577 | n = 255 | n = 322 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Age | |||||||

| 40–49 years | 305 | 52.9 | 132 | 51.8 | 173 | 53.7 | 0.64 † |

| 50–59 years | 272 | 47.1 | 123 | 48.2 | 149 | 46.3 | |

| Living arrangement | |||||||

| Living alone | 25 | 4.3 | 13 | 5.1 | 12 | 3.7 | 0.83 ‡ |

| Married couple | 95 | 16.5 | 42 | 16.5 | 53 | 16.5 | |

| Parent(s) and children | 352 | 61.0 | 158 | 62.0 | 194 | 60.2 | |

| 3- or 4-generation household | 99 | 17.2 | 40 | 15.7 | 59 | 18.3 | |

| Other | 6 | 1.0 | 2 | 0.8 | 4 | 1.2 | |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | |||||||

| <18.5 | 44 | 7.6 | 10 | 3.9 | 34 | 10.6 | <0.001 † |

| ≥18.5 and <25 | 396 | 68.6 | 163 | 63.9 | 233 | 72.4 | |

| ≥25 | 137 | 23.7 | 82 | 32.2 | 55 | 17.1 | |

| Healthy Diets and Related Factors | Men, n = 255 | Women, n = 322 | Interaction (Sex × Age) | Sex | Age Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40–49 Years | 50–59 Years | 40–49 Years | 50–59 Years | ||||||

| n = 132 | n = 123 | n = 173 | n = 149 | ||||||

| Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | ||||||

| SD | SD | SD | SD | ||||||

| Healthy diets | F = 0.220 | F = 14.019 | Men < Women | F = 6.766 | 40–49 < 50–59 | ||||

| Total score (3–13 points) | 8.5 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 9.6 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | ||

| 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 2.0 | p = 0.64 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.010 | |||

| Maintaining appropriate weight | F = 1.012 | F = 49.308 | Men < Women | F = 6.048 | 40–49 < 50–59 | ||||

| Total score (6–24 points) | 13.2 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 16.1 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | ||

| 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.2 | p = 0.32 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.014 | |||

| Frequency of eating rice | F = 0.229 | F = 5.466 | Men > Women | F = 1.277 | |||||

| Total score (3–15 points) | 10.1 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 9.8 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | ||

| 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 | p = 0.63 | p = 0.020 | p = 0.26 | |||

| Eating out frequency | F = 1.233 | F = 23.801 | Men > Women | F = 0.146 | |||||

| Score (1–7 points) | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | ||

| 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | p = 0.28 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.70 | |||

| Frequency of home meal replacement use | F = 0.026 | F = 0.364 | F = 0.215 | ||||||

| Score (1–7 points) | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | df = 1, 573 | ||

| 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | p = 0.87 | p = 0.55 | p = 0.64 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kibayashi, E.; Nakade, M. Healthy Diets Are Associated with Weight Control in Middle-Aged Japanese. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3174. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193174

Kibayashi E, Nakade M. Healthy Diets Are Associated with Weight Control in Middle-Aged Japanese. Nutrients. 2025; 17(19):3174. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193174

Chicago/Turabian StyleKibayashi, Etsuko, and Makiko Nakade. 2025. "Healthy Diets Are Associated with Weight Control in Middle-Aged Japanese" Nutrients 17, no. 19: 3174. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193174

APA StyleKibayashi, E., & Nakade, M. (2025). Healthy Diets Are Associated with Weight Control in Middle-Aged Japanese. Nutrients, 17(19), 3174. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17193174