Differential Associations of Vitamin D Metabolites with Adiposity and Muscle-Related Phenotypes in Korean Adults: Results from KNHANES 2022–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Measurement of Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations

2.3. Measurements of Body Composition Parameters

2.4. Definition of Body Composition Phenotypes

2.5. Other Variables

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population According to Vitamin D Status

3.2. Associations Between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and Body Composition Parameters

3.3. Associations Between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and Body Composition Phenotype

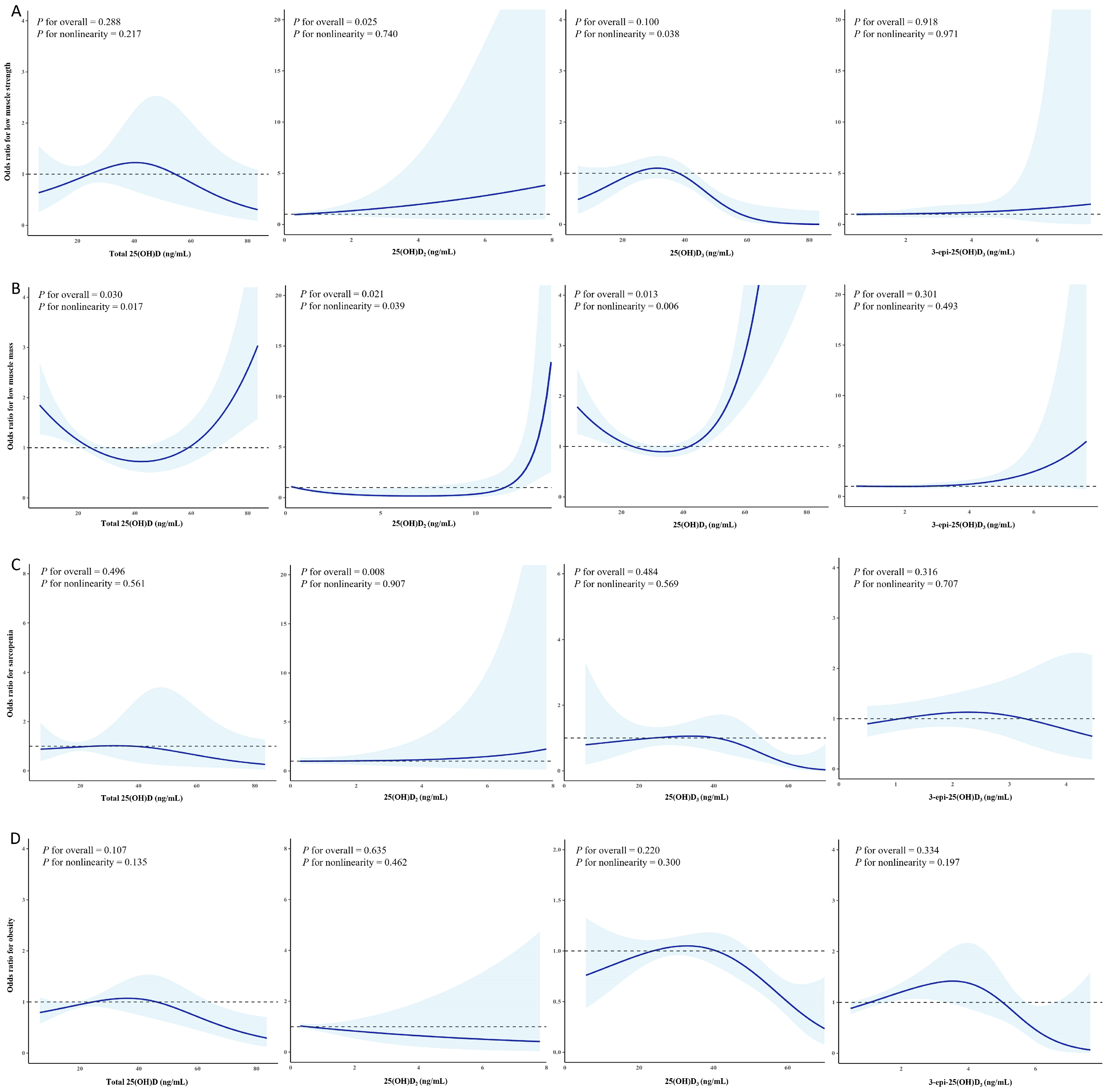

3.4. Non-Linear Relationship Between Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations and Body Composition Phenotype

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASM | Appendicular skeletal muscle mass |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3 | 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 |

| HGS | Handgrip strength |

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| 25(OH)D2 | 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 |

| 25(OH)D3 | 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 |

| KNHANES | The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| WC | Waist circumference |

References

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeland, I.J.; Ayers, C.R.; Rohatgi, A.K.; Turer, A.T.; Berry, J.D.; Das, S.R.; Vega, G.L.; Khera, A.; McGuire, D.K.; Grundy, S.M.; et al. Associations of visceral and abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue with markers of cardiac and metabolic risk in obese adults. Obesity 2013, 21, E439–E447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutcher, S.H.; Dunn, S.L.; Gail Trapp, E.; Freund, J. Regional adiposity distribution and insulin resistance in young Chinese and European Australian women. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2011, 71, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.R.; Chandler-Laney, P.C.; Brock, D.W.; Lara-Castro, C.; Fernandez, J.R.; Gower, B.A. Fat distribution, aerobic fitness, blood lipids, and insulin sensitivity in African-American and European-American women. Obesity 2010, 18, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsukawa, Y.; Misumi, M.; Kim, Y.M.; Yamada, M.; Ohishi, W.; Fujiwara, S.; Nakanishi, S.; Yoneda, M. Body composition and development of diabetes: A 15-year follow-up study in a Japanese population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.T.; Zeng, Q.T.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhou, S.P. Association between relative muscle strength and cardiometabolic multimorbidity in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Acta Diabetol. 2025; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zohily, B.; Al-Menhali, A.; Gariballa, S.; Haq, A.; Shah, I. Epimers of Vitamin D: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, K.R.; Cruzat, V.; Carlessi, R.; Newsholme, P. Mechanisms of vitamin D action in skeletal muscle. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2019, 32, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.-J. Vitamin D Enhancement of Adipose Biology: Implications on Obesity-Associated Cardiometabolic Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argano, C.; Mirarchi, L.; Amodeo, S.; Orlando, V.; Torres, A.; Corrao, S. The Role of Vitamin D and Its Molecular Bases in Insulin Resistance, Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Disease: State of the Art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzik, K.P.; Kaczor, J.J. Mechanisms of vitamin D on skeletal muscle function: Oxidative stress, energy metabolism and anabolic state. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 119, 825–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, J.J.; Nakhuda, A.; Deane, C.S.; Brook, M.S.; Wilkinson, D.J.; Phillips, B.E.; Philp, A.; Tarum, J.; Kadi, F.; Andersen, D.; et al. Overexpression of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) induces skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Mol. Metab. 2020, 42, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, S.E.; Bass, J.J.; Fujita, S.; Wilkinson, D.; Hewison, M.; Atherton, P.J. The Vitamin D/Vitamin D receptor (VDR) axis in muscle atrophy and sarcopenia. Cell. Signal. 2022, 96, 110355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimaleswaran, K.S.; Berry, D.J.; Lu, C.; Tikkanen, E.; Pilz, S.; Hiraki, L.T.; Cooper, J.D.; Dastani, Z.; Li, R.; Houston, D.K.; et al. Causal relationship between obesity and vitamin D status: Bi-directional Mendelian randomization analysis of multiple cohorts. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckey, R.C.; Cheng, C.Y.S.; Slominski, A.T. The serum vitamin D metabolome: What we know and what is still to discover. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 186, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathmann, F.G.; Sadilkova, K.; Laha, T.J.; LeSourd, S.E.; Bornhorst, J.A.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Jack, R. 3-epi-25 hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are not correlated with age in a cohort of infants and adults. Clin. Chim. Acta 2012, 413, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, J.C.; Bradley, J.; Reddy, G.S.; Ray, R.; Wood, R.J. 1 alpha,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 analogs with minimal in vivo calcemic activity can stimulate significant transepithelial calcium transport and mRNA expression in vitro. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996, 329, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Seo, J.D.; Lee, K.; Roh, E.Y.; Yun, Y.M.; Lee, Y.W.; Cho, S.E.; Song, J. Multicenter comparison of analytical interferences of 25-OH vitamin D immunoassay and mass spectrometry methods by endogenous interferents and cross-reactivity with 3-epi-25-OH-vitamin D(3). Pract. Lab. Med. 2024, 38, e00347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouzid, M.; Karaźniewicz-Łada, M.; Pawlak, K.; Burchardt, P.; Kruszyna, Ł.; Główka, F. Measurement of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D2, 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in population of patients with cardiovascular disease by UPLC-MS/MS method. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2020, 1159, 122350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.; Jin, F.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, Z. No independent association between dietary calcium/vitamin D and appendicular lean mass index in middle-aged women: NHANES cross-sectional analysis (2011–2018). Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T.; Inazu, T.; Mizuno, S.; Tominaga, N.; Toda, M.; Toyama, N.; Kawahara, C.; Suzuki, G. Anti-sarcopenic effects of active vitamin D through modulation of anabolic and catabolic signaling pathways in human skeletal muscle: A randomized controlled trial. Metabolism 2025, 168, 156240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Lorente, H.; Ni, J.; Babio, N.; García-Arellano, A.; Romaguera, D.; Martínez, J.A.; Estruch, R.; Sánchez, V.M.; Vidal, J.; Fitó, M.; et al. Dietary vitamin D intake and changes in body composition over three years in older adults with metabolic syndrome. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2025, 29, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Gong, M.; Mao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, W.; Qiu, L.; Huang, X.; Cao, Z.; et al. Analytical performance evaluation and optimization of serum 25(OH)D LC-MS/MS measurement. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2025, 63, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.E.; Han, J.; Chun, G.; Choi, R.; Lee, S.G.; Park, H.D. Assessment of Serum 3-Epi-25-Hydroxyvitamin D(3), 25-Hydroxyvitamin D(3) and 25-Hydroxyvitamin D(2) in the Korean Population With UPLC-MS/MS. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2025, 12, e70098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, S.A.; Camara, J.E.; Burdette, C.Q.; Hahm, G.; Nalin, F.; Kuszak, A.J.; Merkel, J.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Williams, E.L.; Popp, C.; et al. Interlaboratory comparison of 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays: Vitamin D Standardization Program (VDSP) Intercomparison Study 2—Part 2 ligand binding assays—Impact of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(2) and 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) on assay performance. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.P.; David Cheng, T.Y.; Tsai, S.P.; Chan, H.T.; Hsu, H.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Eriksen, M.P. Are Asians at greater mortality risks for being overweight than Caucasians? Redefining obesity for Asians. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.W.; Chou, M.Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 300–307.e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare; The Korean Academy of Medical Sciences; The Korean Academy of Family Medicine. Alcohol Drinking. Available online: https://health.kdca.go.kr/healthinfo/biz/health/main/mainPage/main.do (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intake for Korean; The Korean Nutrition Society: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, S.; Lankila, H.; Koivunen, K.; Hakamäki, M.; Sipilä, S.; Portegijs, E.; Rantanen, T.; Laakkonen, E.K. Vitamin D sufficiency and its relationship with muscle health across the menopausal transition and aging: Finnish cohorts of middle-aged women and older women and men. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 79, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, R.; Isanejad, M.; Davies, I.G.; Mazidi, M. Genetically Determined Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Is Associated with Total, Trunk, and Arm Fat-Free Mass: A Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2022, 26, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pergola, G.; Martino, T.; Zupo, R.; Caccavo, D.; Pecorella, C.; Paradiso, S.; Silvestris, F.; Triggiani, V. 25 Hydroxyvitamin D Levels are Negatively and Independently Associated with Fat Mass in a Cohort of Healthy Overweight and Obese Subjects. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2019, 19, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.R.; Tripkovic, L.; Hart, K.H.; Lanham-New, S.A. Vitamin D deficiency as a public health issue: Using vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 in future fortification strategies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieman, D.C.; Gillitt, N.D.; Shanely, R.A.; Dew, D.; Meaney, M.P.; Luo, B. Vitamin D2 supplementation amplifies eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage in NASCAR pit crew athletes. Nutrients 2013, 6, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanely, R.A.; Nieman, D.C.; Knab, A.M.; Gillitt, N.D.; Meaney, M.P.; Jin, F.; Sha, W.; Cialdella-Kam, L. Influence of vitamin D mushroom powder supplementation on exercise-induced muscle damage in vitamin D insufficient high school athletes. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G. Extrarenal vitamin D activation and interactions between vitamin D2, vitamin D3, and vitamin D analogs. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2013, 33, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.J.; Taylor, R.L.; Reddy, G.S.; Grebe, S.K. C-3 epimers can account for a significant proportion of total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in infants, complicating accurate measurement and interpretation of vitamin D status. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 91, 3055–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.E.; Van Rompay, M.I.; Gordon, C.M.; Goodman, E.; Eliasziw, M.; Holick, M.F.; Sacheck, J.M. Investigation of the C-3-epi-25(OH)D(3) of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) in urban schoolchildren. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, M.G.; Siu-Caldera, M.L.; Weiskopf, A.; Vouros, P.; Cross, H.S.; Peterlik, M.; Reddy, G.S. Differentiation-related pathways of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol metabolism in human colon adenocarcinoma-derived Caco-2 cells: Production of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxy-3epi-cholecalciferol. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 241, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekimoto, H.; Siu-Caldera, M.L.; Weiskopf, A.; Vouros, P.; Muralidharan, K.R.; Okamura, W.H.; Uskokovic, M.R.; Reddy, G.S. 1alpha,25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3: In vivo metabolite of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in rats. FEBS Lett. 1999, 448, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.J.; Ritter, C.; Slatopolsky, E.; Muralidharan, K.R.; Okamura, W.H.; Reddy, G.S. 1Alpha,25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3, a natural metabolite of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, is a potent suppressor of parathyroid hormone secretion. J. Cell. Biochem. 1999, 73, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Chen, M.W.; Peng, C.R.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, D. Association between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and asthma: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018. J. Asthma 2025, 62, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Vitamin D Status | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deficient | Non-Deficient | |||

| N | 2612 | 811 | 1801 | - |

| Total 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 24.2 ± 0.2 | 15.8 ± 0.1 | 28.9 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D2 (ng/mL) | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.5 ± 0.01 | 0.6 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D3 (ng/mL) | 23.7 ± 0.2 | 15.3 ± 0.1 | 28.3 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (ng/mL) | 1.1 ± 0.01 | 0.7 ± 0.01 | 1.3 ± 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 52.2 ± 0.7 | 47.7 ± 1.0 | 54.6 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Sex (females, %) | 51.3 | 47.0 | 53.2 | 0.001 |

| Household income (low, %) | 22.4 | 21.2 | 22.9 | 0.600 |

| Current smoking (%) | 14.4 | 18.8 | 12.4 | <0.001 |

| Heavy drinking (%) | 28.5 | 32.9 | 26.3 | 0.003 |

| Aerobic exercise (yes, %) | 44.9 | 46.6 | 44.2 | 0.200 |

| Resistance exercise (yes, %) | 29.0 | 28.4 | 29.3 | 0.803 |

| Energy intake (kcal/day) | 1761.9 ± 16.0 | 1824.3 ± 31.5 | 1728.8 ± 18.6 | 0.010 |

| Energy from | ||||

| Carbohydrate (%) | 60.3 ± 0.3 | 59.8 ± 0.6 | 60.5 ± 0.4 | 0.259 |

| Fat (%) | 23.7 ± 0.3 | 24.2 ± 0.5 | 23.5 ± 0.3 | 0.172 |

| Protein (%) | 16.0 ± 0.1 | 16.0 ± 0.2 | 16.0 ± 0.1 | 0.957 |

| Fiber intake (g/day) | 25.7 ± 0.4 | 25.2 ± 0.6 | 26.0 ± 0.4 | 0.259 |

| Medical history (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 15.9 | 14.9 | 16.3 | 0.246 |

| Hypertension | 33.7 | 30.7 | 35.1 | 0.130 |

| Dyslipidemia | 32.0 | 27.9 | 33.9 | 0.003 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 85.0 ± 0.2 | 85.9 ± 0.4 | 84.5 ± 0.3 | 0.006 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 0.1 | 24.7 ± 0.2 | 24.2 ± 0.1 | 0.007 |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 33.6 ± 0.3 | 34.4 ± 0.4 | 33.2 ± 0.4 | 0.021 |

| Fat mass (kg) | ||||

| Total | 19.3 ± 0.2 | 20.0 ± 0.3 | 18.9 ± 0.2 | 0.002 |

| Trunk | 9.9 ± 0.1 | 10.3 ± 0.2 | 9.7 ± 0.1 | 0.002 |

| Limbs | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 8.2 ± 0.1 | 0.003 |

| Lean mass (kg) | ||||

| Total | 47.6 ± 0.3 | 48.9 ± 0.4 | 47.0 ± 0.3 | 0.001 |

| Trunk | 27.9 ± 0.1 | 28.5 ± 0.2 | 27.5 ± 0.2 | 0.001 |

| Limbs | 19.8 ± 0.1 | 20.4 ± 0.2 | 19.4 ± 0.2 | 0.001 |

| ASM (kg/m2) | 7.1 ± 0.02 | 7.2 ± 0.04 | 7.1 ± 0.02 | 0.003 |

| Low muscle strength (%) | 7.5 | 6.2 | 8.2 | 0.325 |

| Low muscle mass (%) | 19.5 | 16.9 | 20.6 | 0.126 |

| Sarcopenia (%) | 4.1 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 0.193 |

| Obesity (%) | 36.6 | 38.7 | 35.6 | 0.138 |

| Total 25(OH)D | 25(OH)D2 | 25(OH)D3 | 3-epi-25(OH)D3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | ||

| Unadjusted | Waist circumference (cm) | −0.087 | <0.001 | −0.002 | 0.154 | −0.085 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.575 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.313 | <0.001 | −0.007 | 0.051 | −0.306 | <0.001 | −0.004 | 0.210 | |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | −0.120 | <0.001 | −0.006 | <0.001 | −0.114 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.024 | |

| Fat mass (kg) | |||||||||

| Total | −0.160 | <0.001 | −0.002 | 0.201 | −0.157 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.083 | |

| Trunk | −0.298 | <0.001 | −0.005 | 0.126 | −0.293 | <0.001 | −0.006 | 0.127 | |

| Limbs | −0.325 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.438 | −0.322 | <0.001 | −0.008 | 0.055 | |

| Lean mass (kg) | |||||||||

| Total | −0.147 | <0.001 | −0.006 | <0.001 | −0.141 | <0.001 | −0.004 | 0.001 | |

| Trunk | −0.268 | <0.001 | −0.010 | 0.001 | −0.258 | <0.001 | −0.007 | 0.002 | |

| Limbs | −0.309 | <0.001 | −0.012 | <0.001 | −0.297 | <0.001 | −0.009 | <0.001 | |

| ASM (kg/m2) | −1.280 | <0.001 | 0.052 | 0.001 | −1.228 | <0.001 | −0.031 | 0.005 | |

| Adjusted | Waist circumference (cm) | −0.058 | 0.011 | −0.001 | 0.459 | −0.057 | 0.013 | −0.0004 | 0.784 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.154 | 0.006 | −0.002 | 0.487 | −0.151 | 0.007 | −0.004 | 0.333 | |

| Handgrip strength (kg) | 0.118 | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.073 | 0.123 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.121 | |

| Fat mass (kg) | |||||||||

| Total | −0.115 | 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.281 | −0.113 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.182 | |

| Trunk | −0.195 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.210 | −0.191 | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.199 | |

| Limbs | −0.284 | <0.001 | −0.003 | 0.421 | −0.280 | <0.001 | −0.007 | 0.153 | |

| Lean mass (kg) | |||||||||

| Total | 0.062 | 0.040 | −0.001 | 0.747 | 0.063 | 0.038 | 0.003 | 0.131 | |

| Trunk | 0.104 | 0.051 | −0.0002 | 0.953 | 0.105 | 0.051 | 0.004 | 0.239 | |

| Limbs | 0.135 | 0.041 | −0.003 | 0.551 | 0.138 | 0.037 | 0.008 | 0.064 | |

| ASM (kg/m2) | 0.195 | 0.461 | −0.014 | 0.497 | 0.209 | 0.432 | 0.017 | 0.361 | |

| Unadjusted | p | Model 1 | p | Model 2 | p | Model 3 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total 25(OH)D | ||||||||

| Low muscle strength | 1.033 (1.015−1.051) | <0.001 | 1.009 (0.990−1.029) | 0.369 | 0.989 (0.960−1.019) | 0.476 | 0.988 (0.958−1.019) | 0.433 |

| Low muscle mass | 1.025 (1.013−1.037) | <0.001 | 1.008 (0.995−1.021) | 0.228 | 1.009 (0.992−1.026) | 0.287 | 1.009 (0.992−1.026) | 0.301 |

| Sarcopenia | 1.035 (1.017−1.054) | <0.001 | 1.009 (0.989−1.029) | 0.370 | 0.985 (0.946−1.025) | 0.457 | 0.985 (0.948−1.025) | 0.458 |

| Obesity | 0.978 (0.967−0.989) | <0.001 | 0.981 (0.970−0.993) | 0.002 | 0.987 (0.972−1.002) | 0.082 | 0.989 (0.974−1.004) | 0.133 |

| 25(OH)D2 | ||||||||

| Low muscle strength | 1.269 (1.081−1.490) | 0.004 | 1.164 (1.014−1.337) | 0.031 | 1.266 (1.056−1.518) | 0.011 | 1.279 (1.055−1.552) | 0.013 |

| Low muscle mass | 1.175 (1.030−1.339) | 0.016 | 1.101 (0.986−1.230) | 0.088 | 1.116 (0.903−1.378) | 0.308 | 1.128 (0.913−1.393) | 0.262 |

| Sarcopenia | 1.346 (1.107−1.636) | 0.003 | 1.224 (1.037−1.444) | 0.017 | 1.424 (1.166−1.739) | 0.001 | 1.418 (1.162−1.732) | 0.001 |

| Obesity | 0.948 (0.838−1.073) | 0.400 | 0.975 (0.872−1.090) | 0.653 | 0.922 (0.743−1.143) | 0.456 | 0.942 (0.759−1.169) | 0.589 |

| 25(OH)D3 | ||||||||

| Low muscle strength | 1.030 (1.011−1.049) | 0.002 | 1.007 (0.987−1.027) | 0.516 | 0.986 (0.957−1.017) | 0.369 | 0.985 (0.955−1.016) | 0.333 |

| Low muscle mass | 1.024 (1.012−1.036) | <0.001 | 1.007 (0.994−1.020) | 0.294 | 1.009 (0.991−1.026) | 0.329 | 1.008 (0.991−1.025) | 0.346 |

| Sarcopenia | 1.030 (1.012−1.049) | 0.001 | 1.004 (0.985−1.024) | 0.650 | 0.978 (0.937−1.020) | 0.294 | 0.978 (0.939−1.019) | 0.295 |

| Obesity | 0.978 (0.967−0.989) | <0.001 | 0.981 (0.970−0.993) | 0.002 | 0.987 (0.972−1.002) | 0.091 | 0.989 (0.974−1.004) | 0.143 |

| 3-epi-25(OH)D3 | ||||||||

| Low muscle strength | 1.490 (1.199−1.850) | <0.001 | 1.247 (0.949−1.640) | 0.113 | 1.073 (0.696−1.653) | 0.749 | 1.045 (0.681−1.604) | 0.839 |

| Low muscle mass | 1.159 (1.001−1.343) | 0.049 | 0.999 (0.854−1.170) | 0.993 | 1.121 (0.896−1.404) | 0.317 | 1.166 (0.935−1.454) | 0.173 |

| Sarcopenia | 1.321 (1.070−1.632) | 0.010 | 1.048 (0.805−1.363) | 0.729 | 0.801 (0.462−1.391) | 0.431 | 0.796 (0.469−1.350) | 0.397 |

| Obesity | 0.949 (0.824−1.092) | 0.464 | 0.970 (0.839−1.122) | 0.683 | 1.004 (0.838−1.202) | 0.967 | 0.961 (0.798−1.157) | 0.675 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.-H.; Jeong, Y.; Son, S.-W.; Kim, H.-N. Differential Associations of Vitamin D Metabolites with Adiposity and Muscle-Related Phenotypes in Korean Adults: Results from KNHANES 2022–2023. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17183013

Kim S-H, Jeong Y, Son S-W, Kim H-N. Differential Associations of Vitamin D Metabolites with Adiposity and Muscle-Related Phenotypes in Korean Adults: Results from KNHANES 2022–2023. Nutrients. 2025; 17(18):3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17183013

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Se-Hong, Yuji Jeong, Seok-Won Son, and Ha-Na Kim. 2025. "Differential Associations of Vitamin D Metabolites with Adiposity and Muscle-Related Phenotypes in Korean Adults: Results from KNHANES 2022–2023" Nutrients 17, no. 18: 3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17183013

APA StyleKim, S.-H., Jeong, Y., Son, S.-W., & Kim, H.-N. (2025). Differential Associations of Vitamin D Metabolites with Adiposity and Muscle-Related Phenotypes in Korean Adults: Results from KNHANES 2022–2023. Nutrients, 17(18), 3013. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17183013