Talking About Weight with Children: Associations with Parental Stigma, Bias, Attitudes, and Child Weight Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

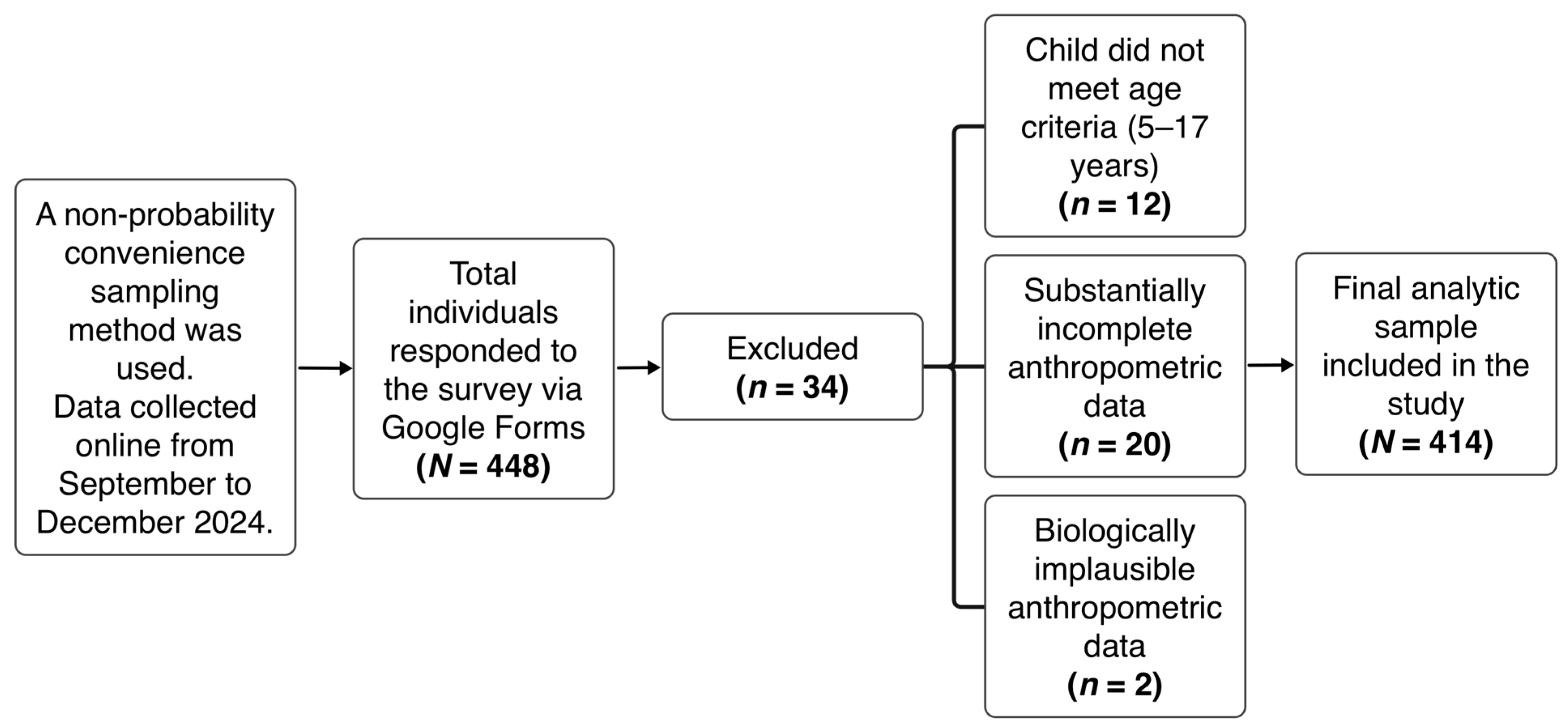

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data and Measurement

2.2.1. Demographics

2.2.2. Anthropometrics

2.2.3. Parental Health and Weight Conversations

2.2.4. Parental Weight Comments

2.2.5. Experienced Weight Stigma

2.2.6. Internalized Weight Bias

2.2.7. Antifat Attitudes (AFA)

2.2.8. Universal Measure of Bias (UMBFAT)

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Child Characteristics

3.3. Parental Communication, Stigma, Bias, and Attitude Measures

3.4. Differences in Parental Communication by Child Weight Status

3.5. Bivariate Correlations Between Parental Psychological Factors, Communication Patterns, and Relevant Parent/Child Characteristics

3.6. Predictors of Parental Weight and Health Communication

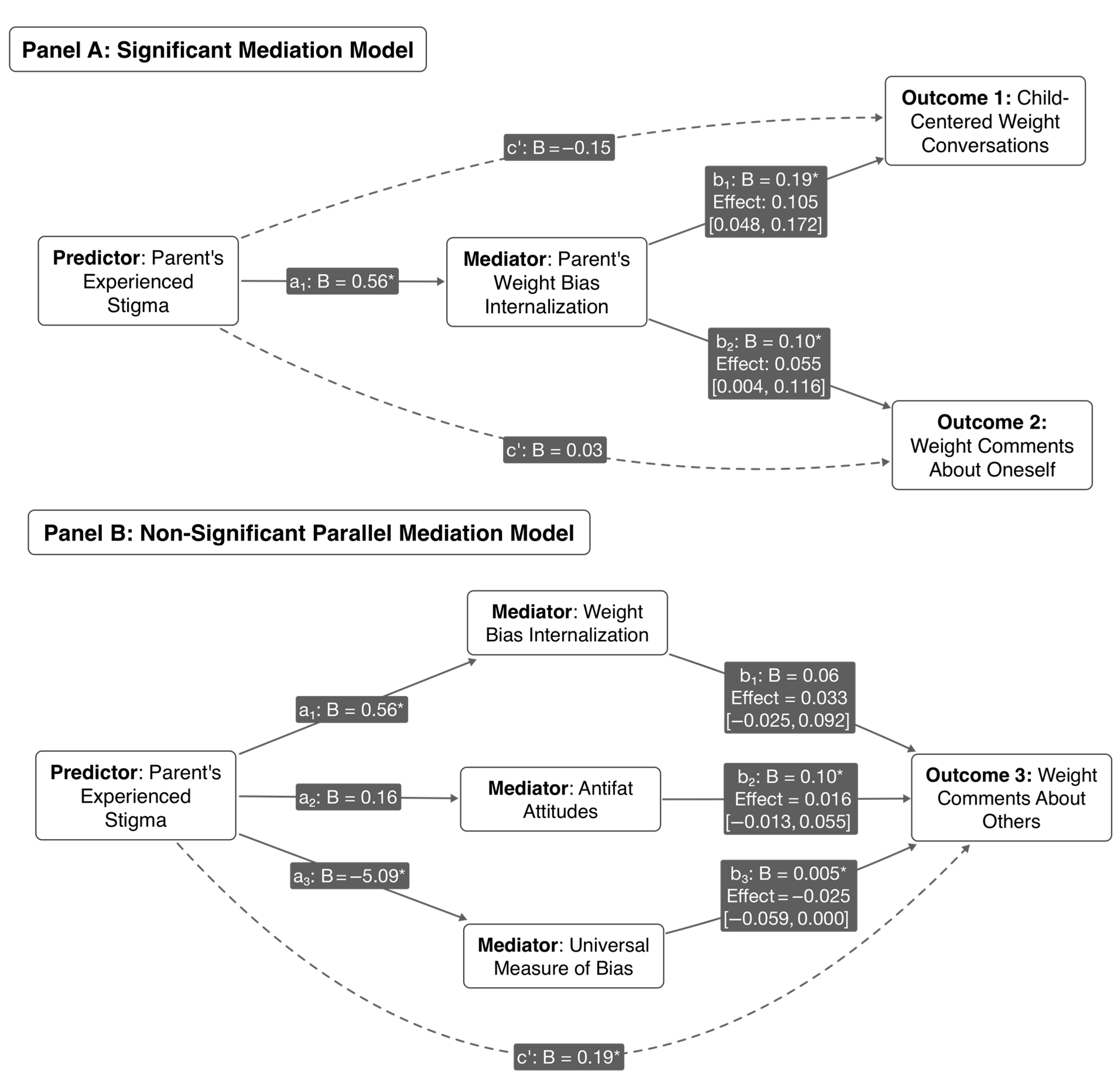

3.7. Mediation Analyses: The Role of Internalized Weight Bias and Attitudes

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings and Interpretations

4.2. The Nuanced Role of Stigma, Bias, and Health Communication

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Implications for Practice

4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- World Obesity Federation. Romania|World Obesity Federation Global Obesity Observatory. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/country/romania-178/ (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Institutul Național de Sănătate Publică. Evaluarea StărII de Sănătate COPII—EHES Raport (Child Health Assessment—EHES Report). Available online: https://www.insmc.ro/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/EHES-01-9535-V9.0_Final.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Serbin, L.A.; Hubert, M.; Hastings, P.D.; Stack, D.M.; Schwartzman, A.E. The influence of parenting on early childhood health and health care utilization. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014, 39, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanos-Nanclares, A.; Zazpe, I.; Santiago, S.; Marin, L.; Rico-Campa, A.; Martin-Calvo, N. Influence of Parental Healthy-Eating Attitudes and Nutritional Knowledge on Nutritional Adequacy and Diet Quality among Preschoolers: The SENDO Project. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, L.; Flores-Barrantes, P.; Moreno, L.A.; Manios, Y.; Gonzalez-Gil, E.M. The Influence of Parental Dietary Behaviors and Practices on Children’s Eating Habits. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Hilbert, A. Interaction Effects of Child Weight Status and Parental Feeding Practices on Children’s Eating Disorder Symptomatology. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Gil, J.F.; Victoria-Montesinos, D.; Gutierrez-Espinoza, H.; Jimenez-Lopez, E. Family Meals and Social Eating Behavior and Their Association with Disordered Eating among Spanish Adolescents: The EHDLA Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoli, M.; Scotto Rosato, M.; Cipriano, A.; Napolano, R.; Cotrufo, P.; Barberis, N.; Cella, S. Affect, Body, and Eating Habits in Children: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callender, C.; Velazquez, D.; Adera, M.; Dave, J.M.; Olvera, N.; Chen, T.A.; Alford, S.; Thompson, D. How Minority Parents Could Help Children Develop Healthy Eating Behaviors: Parent and Child Perspectives. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, J.M.; Vander Weg, M.W. Investigating the relationship between parental weight stigma and feeding practices. Appetite 2020, 149, 104635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Tang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Min, K.; Su, F.; Wang, J.; Liao, W.; Yan, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. How Parenting and Family Characteristics Predict the Use of Feeding Practices among Parents of Preschoolers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Beijing, China. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, K.A.; Uy, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Fisher, J.O.; Berge, J.M. A qualitative exploration into momentary impacts on food parenting practices among parents of pre-school aged children. Appetite 2018, 130, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.M.; Tate, A.; Trofholz, A.; Loth, K.; Miner, M.; Crow, S.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Examining variability in parent feeding practices within a low-income, racially/ethnically diverse, and immigrant population using ecological momentary assessment. Appetite 2018, 127, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler, J.; Schmidt, R.; Poulain, T.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Hilbert, A. Stability, Continuity, and Bi-Directional Associations of Parental Feeding Practices and Standardized Child Body Mass Index in Children from 2 to 12 Years of Age. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.L.; Hoeft, K.S.; Takayama, J.I.; Barker, J.C. Beliefs and practices regarding solid food introduction among Latino parents in Northern California. Appetite 2018, 120, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.A.; Staton, S.; Morawska, A.; Gallegos, D.; Oakes, C.; Thorpe, K. A comparison of maternal feeding responses to child fussy eating in low-income food secure and food insecure households. Appetite 2019, 137, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yong, C.; Xi, Y.; Huo, J.; Zou, H.; Liang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Lin, Q. Association between Parents’ Perceptions of Preschool Children’s Weight, Feeding Practices and Children’s Dietary Patterns: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lydecker, J.A.; Riley, K.E.; Grilo, C.M. Associations of parents’ self, child, and other “fat talk” with child eating behaviors and weight. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Imani, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Su, J.A.; Latner, J.D.; Marshall, R.D.; Pakpour, A.H. A prospective study on the link between weight-related self-stigma and binge eating: Role of food addiction and psychological distress. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potzsch, A.; Rudolph, A.; Schmidt, R.; Hilbert, A. Two sides of weight bias in adolescent binge—eating disorder: Adolescents’ perceptions and maternal attitudes. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.A.; Ria-Searle, B.; Jansen, E.; Thorpe, K. What’s the fuss about? Parent presentations of fussy eating to a parenting support helpline. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.M.; Fertig, A.R.; Trofholz, A.; de Brito, J.N. Real-time predictors of food parenting practices and child eating behaviors in racially/ethnically diverse families. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eeden, A.E.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Risk factors in preadolescent boys and girls for the development of eating pathology in young adulthood. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1147–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Wertheim, E.H.; Damiano, S.R.; Paxton, S.J. Maternal influences on body image and eating concerns among 7- and 8-year-old boys and girls: Cross—Sectional and prospective relations. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Lessard, L.M.; Foster, G.D.; Cardel, M.I. A Comprehensive Examination of the Nature, Frequency, and Context of Parental Weight Communication: Perspectives of Parents and Adolescents. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.J.; Haycraft, E. Parental body dissatisfaction and controlling child feeding practices: A prospective study of Australian parent-child dyads. Eat. Behav. 2019, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.R.; Berge, J.M.; Larson, N.; Loth, K.A.; Wall, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parent-child health- and weight-focused conversations: Who is saying what and to whom? Appetite 2018, 126, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarychta, K.; Banik, A.; Kulis, E.; Boberska, M.; Radtke, T.; Chan, C.K.Y.; Luszczynska, A. Parental Depression Predicts Child Body Mass via Parental Support Provision, Child Support Receipt, and Child Physical Activity: Findings From Parent/Caregiver—Child Dyads. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, J.; Downing, K.L.; Tang, L.; Campbell, K.J.; Hesketh, K.D. Associations between maternal concern about child’s weight and related behaviours and maternal weight-related parenting practices: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwiejczyk, L.; Mehta, K.; Scott, J.; Tonkin, E.; Coveney, J. Characteristics of Effective Interventions Promoting Healthy Eating for Pre-Schoolers in Childcare Settings: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayine, P.; Selvaraju, V.; Venkatapoorna, C.M.K.; Geetha, T. Parental Feeding Practices in Relation to Maternal Education and Childhood Obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Rosso, S.; Nicklaus, S.; Ducrot, P.; Schwartz, C. Information seeking of French parents regarding infant and young child feeding: Practices, needs and determinants. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 879–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozma-Petrut, A.; Filip, L.; Banc, R.; Mirza, O.; Gavrilas, L.; Ciobarca, D.; Badiu-Tisa, I.; Heghes, S.C.; Popa, C.O.; Miere, D. Breastfeeding Practices and Determinant Factors of Exclusive Breastfeeding among Mothers of Children Aged 0–23 Months in Northwestern Romania. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makela, I.; Koivuniemi, E.; Vahlberg, T.; Raats, M.M.; Laitinen, K. Self-Reported Parental Healthy Dietary Behavior Relates to Views on Child Feeding and Health and Diet Quality. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Body Mass Index-For-Age (BMI-For-Age). Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/growth-reference-data-for-5to19-years/indicators/bmi-for-age (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Berge, J.M.; MacLehose, R.F.; Loth, K.A.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Parent-adolescent conversations about eating, physical activity and weight: Prevalence across sociodemographic characteristics and associations with adolescent weight and weight-related behaviors. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudney, E.V.; Himmelstein, M.S.; Puhl, R.M. The role of weight stigma in parental weight talk. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.W.; Bucchianeri, M.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Mother-reported parental weight talk and adolescent girls’ emotional health, weight control attempts, and disordered eating behaviors. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.; Sarda, V. Framing messages about weight discrimination: Impact on public support for legislation. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.L.; Puhl, R.M. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: Validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image 2014, 11, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Himmelstein, M.S.; Quinn, D.M. Internalizing Weight Stigma: Prevalence and Sociodemographic Considerations in US Adults. Obesity 2018, 26, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C.S. Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.R.; Rosen, L.H. Predicting anti-fat attitudes: Individual differences based on actual and perceived body size, weight importance, entity mindset, and ethnicity. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2015, 20, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latner, J.D.; O’Brien, K.S.; Durso, L.E.; Brinkman, L.A.; MacDonald, T. Weighing obesity stigma: The relative strength of different forms of bias. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 1145–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. The PROCESS macro for SPSS, SAS, and R. Available online: https://www.processmacro.org/index.html (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Yourell, J.L.; Doty, J.L.; Beauplan, Y.; Cardel, M.I. Weight-Talk Between Parents and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Relationships with Health-Related and Psychosocial Outcomes. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2021, 6, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, L.M.; Puhl, R.M.; Foster, G.D.; Cardel, M.I. Parental Communication About Body Weight and Adolescent Health: The Role of Positive and Negative Weight-Related Comments. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahill, L.; Mitchison, D.; Morrison, N.M.V.; Touyz, S.; Bussey, K.; Trompeter, N.; Lonergan, A.; Hay, P. Prevalence of Parental Comments on Weight/Shape/Eating amongst Sons and Daughters in an Adolescent Sample. Nutrients 2021, 13, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eli, K.; Neovius, C.; Nordin, K.; Brissman, M.; Ek, A. Parents’ experiences following conversations about their young child’s weight in the primary health care setting: A study within the STOP project. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatham, R.E.; Mixer, S.J. Cultural Influences on Childhood Obesity in Ethnic Minorities: A Qualitative Systematic Review. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2020, 31, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahill, L.; Touyz, S.; Morrison, N.; Hay, P. Parental appearance teasing in adolescence and associations with eating problems: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haqq, A.M.; Kebbe, M.; Tan, Q.; Manco, M.; Salas, X.R. Complexity and Stigma of Pediatric Obesity. Child. Obes. 2021, 17, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.M.; Flint, S.W.; Clare, K.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Rothwell, E.R.; Bould, H.; Howe, L.D. Demographic, socioeconomic and life-course risk factors for internalized weight stigma in adulthood: Evidence from an English birth cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 40, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menor-Rodriguez, M.J.; Cortes-Martin, J.; Rodriguez-Blanque, R.; Tovar-Galvez, M.I.; Aguilar-Cordero, M.J.; Sanchez-Garcia, J.C. Influence of an Educational Intervention on Eating Habits in School-Aged Children. Children 2022, 9, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeau, K.; Carbonneau, N.; Pelletier, L. Family members and peers’ negative and positive body talk: How they relate to adolescent girls’ body talk and eating disorder attitudes. Body Image 2022, 40, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidstrup, H.; Brennan, L.; Hindle, A.; Kaufmann, L.; de la Piedad Garcia, X. Internalised Weight Stigma Mediates Relationships Between Perceived Weight Stigma and Psychosocial Correlates in Individuals Seeking Bariatric Surgery: A Cross-sectional Study. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 3675–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pudney, E.V.; Puhl, R.M.; Halgunseth, L.C.; Schwartz, M.B. An Examination of Parental Weight Stigma and Weight Talk Among Socioeconomically and Racially/Ethnically Diverse Parents. Fam. Community Health 2024, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Himmelstein, M.S. Weight Bias Internalization Among Adolescents Seeking Weight Loss: Implications for Eating Behaviors and Parental Communication. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrig, A.; Schmidt, R.; Mansfeld, T.; Sander, J.; Seyfried, F.; Kaiser, S.; Stroh, C.; Dietrich, A.; Hilbert, A. Depressive Symptoms among Bariatric Surgery Candidates: Associations with Stigmatization and Weight and Shape Concern. Nutrients 2024, 16, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerend, M.A.; Sutin, A.R.; Terracciano, A.; Maner, J.K. The role of psychological attribution in responses to weight stigma. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, C.M.; Miller, H.N.; Brooks, T.L.; Mo-Hunter, L.; Steinberg, D.M.; Bennett, G.G. Designing Ruby: Protocol for a 2-Arm, Brief, Digital Randomized Controlled Trial for Internalized Weight Bias. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e31307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K.E.; Hart, L.M.; Paxton, S.J. Confident Body, Confident Child: Outcomes for Children of Parents Receiving a Universal Parenting Program to Promote Healthful Eating Patterns and Positive Body Image in Their Pre-Schoolers-An Exploratory RCT Extension. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Lessard, L.M.; Foster, G.D.; Cardel, M.I. Parent—child communication about weight: Priorities for parental education and support. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffoul, A.; Williams, L. Integrating Health at Every Size principles into adolescent care. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2021, 33, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Ramos, J.; Mendoza-Munoz, M.; Castillo-Paredes, A.; Galan-Arroyo, C. Influence of Parental Perception of Child’s Physical Fitness on Body Image Satisfaction in Spanish Preschool Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, L.N.; Hart, L.M.; Butel, F.E.; Roberts, S. Child health nurse perceptions of using confident body, confident child in community health: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.C.; Walczak, M.; Roach, E.; Lumeng, J.C.; Miller, A.L. Longitudinal associations between eating and drinking engagement during mealtime and eating in the absence of hunger in low income toddlers. Appetite 2018, 130, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamody, R.C.; Lydecker, J.A. Parental feeding practices and children’s disordered eating among single parents and co-parents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, H.J. Maternal self-rated health and psychological distress predict early feeding difficulties: Results from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 1312–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeier, H.; Paxton, S.J.; Milgrom, J.; Anderson, S.E.; Baur, L.; Hill, B.; Lim, S.; Green, R.; Skouteris, H. Early mother-child dyadic pathways to childhood obesity risk: A conceptual model. Appetite 2020, 144, 104459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, L.; Vizcarra, M.; Hughes, S.O.; Papaioannou, M.A. Food Parenting Practices and Feeding Styles and Their Relations with Weight Status in Children in Latin America and the Caribbean. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Warkentin, S.; Jansen, E.; Carnell, S. Acculturation, food-related and general parenting, and body weight in Chinese-American children. Appetite 2022, 168, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group | <40 years | 174 | 42.0 |

| ≥40 years | 240 | 58 | |

| Gender | Female | 380 | 91.8 |

| Male | 32 | 7.7 | |

| Prefer not to declare | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Educational Attainment | Lower Education | 89 | 21.5 |

| Higher Education | 325 | 78.5 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 371 | 89.6 |

| Divorced/Widowed/Never married | 43 | 10.4 | |

| Employment Status | Employed | 291 | 70.3 |

| Domestic worker a | 38 | 9.2 | |

| Entrepreneur/Self-employed | 85 | 20.5 | |

| Number of Children b | 1 Child | 149 | 37.1 |

| 2 Children | 216 | 53.7 | |

| 3 Children | 37 | 9.2 | |

| BMI Classification | Underweight (<18.5) | 11 | 2.7 |

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 251 | 60.6 | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 100 | 24.2 | |

| Obese (≥30) | 52 | 12.6 | |

| Self-Rated Health | Poor | 2 | 0.5 |

| Acceptable | 79 | 19.1 | |

| Good | 208 | 50.2 | |

| Very good | 113 | 27.3 | |

| Don’t know/Prefer not to answer | 12 | 2.9 | |

| Long-term Morbidity | Yes | 91 | 22 |

| No | 273 | 65.9 | |

| Don’t know/Prefer not to answer | 50 | 12.1 |

| Characteristic | Statistic | n | Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 225 | 54.30% |

| Male | 180 | 43.50% | |

| Prefer not to declare | 9 | 2.20% | |

| Age (Years) | Mean (SD) | 414 | 10.05 (1.71) |

| Range | 414 | 5–17 | |

| BMI | Mean (SD) | 414 | 18.09 (4.56) |

| Range | 414 | 12.08–62.22 | |

| BMI Percentile b | Mean (SD) | 405 | 59.29 (33.48) |

| Median | 405 | 75 | |

| Range | 405 | 5.00–100.00 | |

| Weight Status b | <5th (Underweight) | 42 | 10.40% |

| 5th–<85th (Healthy Weight) | 218 | 53.80% | |

| 85th–<95th (Overweight) | 55 | 13.60% | |

| ≥95th (Obesity) | 90 | 22.20% |

| Measure | M | SD | Possible Range | Observed Range | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | |||||

| Health Conversations | 3.84 | 0.73 | 1–5 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.77 |

| Weight Conversations | 2.31 | 0.96 | 1–5 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.85 |

| Comments Own Weight | 2.74 | 0.89 | 1–4 | 1–4 | N/A |

| Comments Others’ Weight | 2.01 | 0.88 | 1–4 | 1–4 | N/A |

| Comments Diet/Exercise | 2.76 | 0.87 | 1–4 | 1–4 | N/A |

| Stigma & Bias/Attitudes | |||||

| Experienced Stigma (% Yes) a | 44.70% | - | 0–1 | 0–1 | N/A |

| Internalized Weight Bias | 1.95 | 1.23 | 1–7 | 1.00–7.00 | 0.94 |

| AFA Total | 2.62 | 1.48 | 0–9 | 0.00–8.46 | 0.87 |

| AFA Dislike | 1.87 | 1.39 | 0–9 | 0.00–8.00 | 0.82 |

| AFA Fear | 3 | 2.31 | 0–9 | 0.00–9.00 | 0.85 |

| AFA Willpower | 3.99 | 2.42 | 0–9 | 0.00–9.00 | 0.88 |

| UMBFAT Total b | 65.99 | 20.16 | 20–140 | 22–129 | 0.84 |

| UMBFAT Negative Judgment b | 14.25 | 9.13 | 5–35 | 5–35 | 0.94 |

| UMBFAT Distance b | 16.33 | 6 | 5–35 | 5–35 | 0.57 |

| UMBFAT Attraction b | 19.85 | 6.05 | 5–35 | 5–35 | 0.71 |

| UMBFAT Equal Rights b | 15.56 | 10.23 | 5–35 | 5–35 | 0.96 |

| Variable/Group | N | M (SD) | Test Statistic | df | p-Value | Games-Howell |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Conversations | F = 55.91 | 3, 401 | <0.001 | UW = HW < OW < OB | ||

| Underweight | 42 | 1.87 (0.69) a | ||||

| Healthy Weight | 218 | 1.96 (0.73) a | ||||

| Overweight | 55 | 2.51 (0.92) b | ||||

| Obesity | 90 | 3.21 (0.96) c | ||||

| Comments about Own Weight | F = 2.96 | 3, 401 | 0.032 | HW < OB | ||

| Underweight | 42 | 2.74 (0.89) ab | ||||

| Healthy Weight | 218 | 2.64 (0.89) a | ||||

| Overweight | 55 | 2.75 (0.91) ab | ||||

| Obesity | 90 | 2.97 (0.85) b | ||||

| Comments about Others’ Weight | F = 4.85 | 3, 401 | 0.003 | HW < OB | ||

| Underweight | 42 | 2.24 (0.93) ab | ||||

| Healthy Weight | 218 | 1.86 (0.79) a | ||||

| Overweight | 55 | 2.11 (0.96) ab | ||||

| Obesity | 90 | 2.20 (0.96) b |

| Variable | Experienced Stigma | Internalized Weight Bias | AFA Total | UMBFAT Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication Patterns | ||||

| Health Conversations | −0.01 | −0.08 | 0.06 | −0.05 |

| Weight Conversations | 0.01 | 0.24 *** | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| Comments: Own Weight | 0.06 | 0.11 * | 0.12 * | 0.03 |

| Comments: Others’ Weight | 0.12 * | 0.11 * | 0.21 *** | 0.14 ** |

| Comments: Diet/PA | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.12 * | −0.01 |

| Parent/Child Characteristics | ||||

| Parental SRH | −0.14 ** | −0.36 *** | −0.14 ** | −0.03 |

| Parental Chronic Morbidity | −0.20 *** | −0.17 ** | −0.07 | −0.02 |

| Parental BMI | 0.23 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Child’s Age | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.12 * | −0.02 |

| Child BMI Percentile | 0.12 * | 0.21 *** | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Dependent Variable | Overall Model Adj. R2 | ΔR2 for Main Predictors | Significant Predictors (β) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Conversations | 0.306 *** | 0.048 *** | Covariates: Child Age (0.18 ***), Child BMI percentile (0.44 ***) Main Predictors: Experienced Stigma (−0.09 *), Internalized Bias (0.25 ***) |

| Comments: Own Weight | 0.092 *** | 0.023 * | Covariates: Parent Education (0.20 ***), Child Age (0.21 ***) Main Predictors: Internalized Bias (0.13 *) |

| Comments: Others’ Weight | 0.084 *** | 0.082 *** | Covariates: Parent BMI (−0.12 *) Main Predictors: Antifat Attitudes (0.17 **), UMBFAT (0.11 *) |

| Comments: Diet/Exercise | 0.039 ** | 0.014 | Covariates: Parent Education (0.20 ***) Main Predictors: None |

| Health Conversations | 0.045 ** | 0.006 | Covariates: Parent Education (0.20 ***), Parent SRH (0.15 **), Parent BMI (−0.12 *) Main Predictors: None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ispas, A.G.; Forray, A.I.; Lacurezeanu, A.; Petreuș, D.; Gavrilaș, L.I.; Cherecheș, R.M. Talking About Weight with Children: Associations with Parental Stigma, Bias, Attitudes, and Child Weight Status. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182920

Ispas AG, Forray AI, Lacurezeanu A, Petreuș D, Gavrilaș LI, Cherecheș RM. Talking About Weight with Children: Associations with Parental Stigma, Bias, Attitudes, and Child Weight Status. Nutrients. 2025; 17(18):2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182920

Chicago/Turabian StyleIspas, Anca Georgiana, Alina Ioana Forray, Alexandra Lacurezeanu, Dumitru Petreuș, Laura Ioana Gavrilaș, and Răzvan Mircea Cherecheș. 2025. "Talking About Weight with Children: Associations with Parental Stigma, Bias, Attitudes, and Child Weight Status" Nutrients 17, no. 18: 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182920

APA StyleIspas, A. G., Forray, A. I., Lacurezeanu, A., Petreuș, D., Gavrilaș, L. I., & Cherecheș, R. M. (2025). Talking About Weight with Children: Associations with Parental Stigma, Bias, Attitudes, and Child Weight Status. Nutrients, 17(18), 2920. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17182920