Knowledge of Salt, Oil, and Sugar Reduction (“Three Reductions”) and Its Association with Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases in Chinese Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

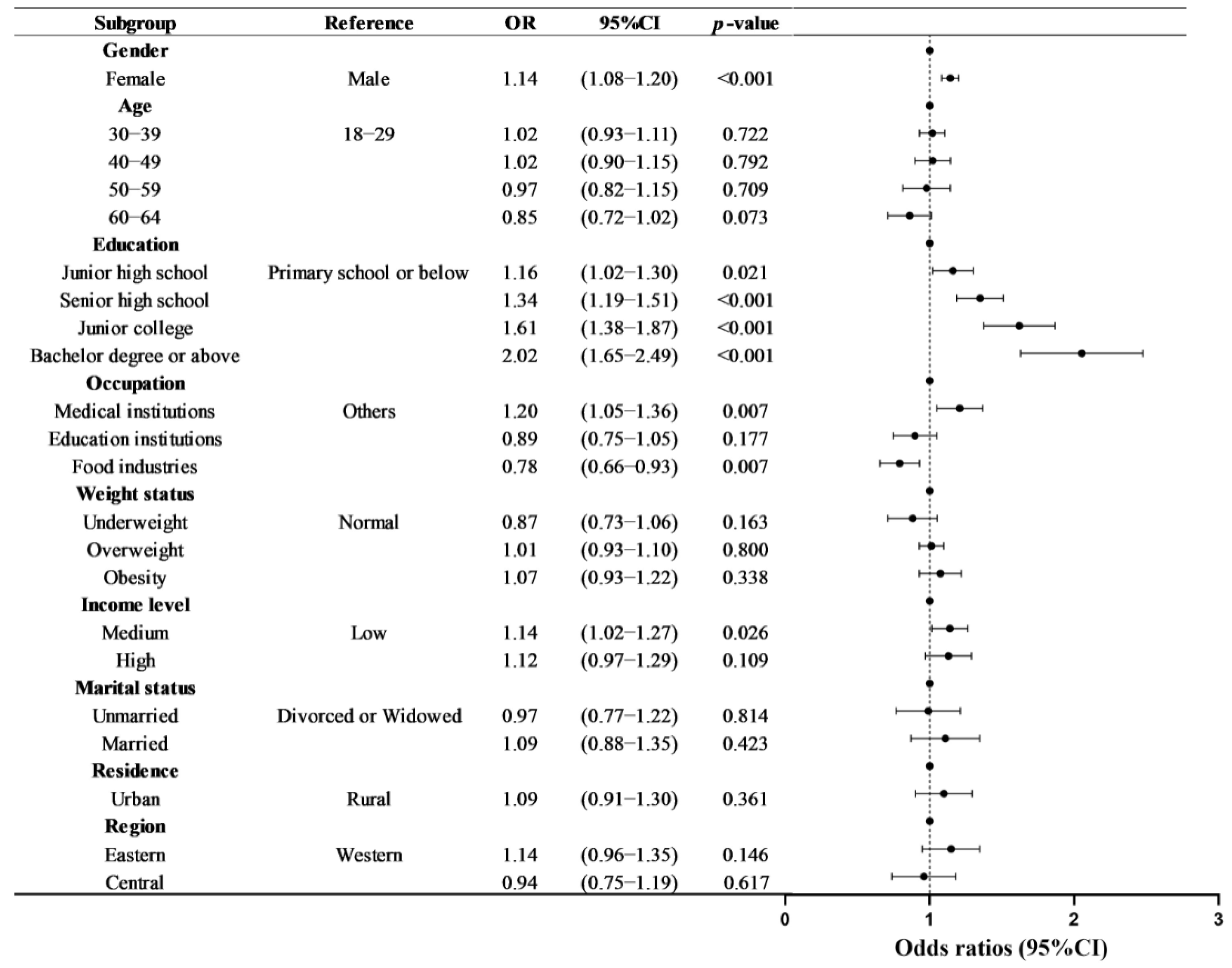

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics

3.2. “Three Reductions” Knowledge Level

3.3. The “Three Reductions” Knowledge Items

3.4. The Association with “Three Reductions” Knowledge Level and Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2021 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 288 causes of death and life expectancy decomposition in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2100–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yin, P.; Qi, J.; Zhou, M. Burden of non-communicable diseases in China and its provinces, 1990–2021: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2325–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases The Writing Committee of the Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China. Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China 2024: An Updated Summary. Chin. Circ. J. 2025, 40, 521–559. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, L.; Liu, M.; Fan, J.; Hu, S. Summary of the 2022 Report on Cardiovascular Health and Diseases in China. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 2899–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Diet Collaborators. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wan, L.; Chen, W. Associations between Total and Added Sugar Intake and Diabetes among Chinese Adults: The Role of Body Mass Index. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, P.; Mao, L.; Wu, F.; Wang, J.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, Y. Cooking Oil Consumption Is Positively Associated with Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in a Chinese Nationwide Cohort Study. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Hemler, E.C.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, L.; et al. The dietary transition and its association with cardiometabolic mortality among Chinese adults, 1982–2012: A cross-sectional population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, T.; Dong, W.; Chu, C.; Zhou, M. Study on the death and disease burden caused by high sugar-sweetened beverages intake in China from 1990 to 2019. Eur. J. Public Health 2022, 32, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ding, G.; Zhao, W. Nutrition and Health Surveillance Report of Chinese Residents from 2015 to 2017; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for China 2023; People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Du, W.; Su, C.; Jia, X.; Huang, F.; Wei, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Li, L.; Bai, J.; et al. Food intake among adult residents in 10 provinces (autonomous regions) of China in 2022–2023. J. Hyg. Res. 2024, 53, 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents (2022); People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Yu, D.; Zhao, L. Trend of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and intake of added sugar in China nine provinces among adults. J. Hyg. Res. 2014, 43, 70–72. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.J.; Pombo-Rodrigues, S.; Macgregor, G.A. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: Its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.X.; Arcand, J.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Johnson, C.; Malta, D.; Petersen, K.; Rae, S.; Santos, J.A.; Sivakumar, B.; Thout, S.R.; et al. The World Hypertension League Science of Salt: A regularly updated systematic review of salt and health outcomes studies (Sept 2019 to Dec 2020). J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 36, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.; Martin, N.; Jimoh, O.F.; Kirk, C.; Foster, E.; Abdelhamid, A.S. Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD011737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; He, F.J.; Yin, Y.; Hashem, K.M.; MacGregor, G.A. Gradual reduction of sugar in soft drinks without substitution as a strategy to reduce overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes: A modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; He, F.; Morris, J.K.; MacGregor, G. Reducing daily salt intake in China by 1 g could prevent almost 9 million cardiovascular events by 2030: A modelling study. BMJ Nutr. Prev. Health 2022, 5, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalidi, H.; Mohtadi, K.; Msaad, R.; Benalioua, N.; Lebrazi, H.; Kettani, A.; Taki, H.; Saïle, R. The association between nutritional knowledge and eating habits among a representative adult population in Casablanca City, Morocco. Nutr. Clin. Métabolisme 2022, 36, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Lucia, F.; Olivieri, M.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Bonanni, A.; Moli-sani Project Investigators. Nutrition knowledge is associated with higher adherence to Mediterranean diet and lower prevalence of obesity. Results from the Moli-sani study. Appetite 2013, 68, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, I.J.; Chang, L.C.; Lee, C.K.; Liao, L.L. Nutrition Literacy Mediates the Relationships between Multi-Level Factors and College Students’ Healthy Eating Behavior: Evidence from a Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balani, R.; Herrington, H.; Bryant, E.; Lucas, C.; Kim, S.C. Nutrition knowledge, attitudes, and self-regulation as predictors of overweight and obesity. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2019, 31, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Nie, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Luo, R.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; He, F.J. Salt-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors and Their Relationship with 24-Hour Urinary Sodium Excretion in Chinese Adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Healthy Lifestyle for All Programme (2017–2025). Available online: https://www.chinacdc.cn/jiankang121/flfg/wbzl/202210/t20221013_261555.html (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Ding, C.; Qiu, Y.; Li, W.; Yuan, F.; Gong, W.; Chen, Z.; Liu, A. Expert consistency evaluation on nutrition and health knowledge questionnaire items for Chinese adults. J. Hyg. Res. 2022, 51, 866–870. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Gong, W.; Zhou, Y.; Song, C.; Feng, J.; Zhang, W.; Liu, A. The Nutrition Knowledge Level and Influencing Factors among Chinese Women Aged 18–49 Years in 2021: Data from a Nationally Representative Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.F. Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults—study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed. Environ. Sci. BES 2002, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2023; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. China Health Statistics Yearbook 2022; China Union Medical College Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Peng, W.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Z.; Song, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.; Sun, X.; et al. Prevalence and Treatment of Diabetes in China, 2013–2018. JAMA 2021, 326, 2498–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, L. Salt-Related Knowledge, Behaviors, and Associated Factors Among Chinese Adults—China, 2015. China CDC Wkly. 2020, 2, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Zhao, B.; Hao, L.; Gong, W.; Feng, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, A. Geographical distribution differences of nutrition and health knowledge among Chinese adults in 2021. J. Hyg. Res. 2022, 51, 881–885. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Su, C.; Du, W.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, H. Changes in the awareness of nutritional knowledge in Chinese adults during 2004–2015. J. Hyg. Res. 2020, 49, 345–356. [Google Scholar]

- De Vriendt, T.; Matthys, C.; Verbeke, W.; Pynaert, I.; De Henauw, S. Determinants of nutrition knowledge in young and middle-aged Belgian women and the association with their dietary behaviour. Appetite 2009, 52, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.B.; Vasconcelos, S.M.; Correia, L.O.; Ferreira, R.C. Nutrition knowledge assessment studies in adults: A systematic review. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2016, 21, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.J.; Abbott, G.; Spence, A.C.; Crawford, D.A.; McNaughton, S.A.; Ball, K. Home food availability mediates associations between mothers’ nutrition knowledge and child diet. Appetite 2013, 71, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankumbi, J.; Muliira, J.K. Barriers to infant and child-feeding practices: A qualitative study of primary caregivers in Rural Uganda. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koch, F.; Hoffmann, I.; Claupein, E. Types of Nutrition Knowledge, Their Socio-Demographic Determinants and Their Association with Food Consumption: Results of the NEMONIT Study. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 630014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliemann, N.; Wardle, J.; Johnson, F.; Croker, H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalvedi, M.L.; Gennaro, L.; Saba, A.; Rossi, L. Relationship Between Nutrition Knowledge and Dietary Intake: An Assessment Among a Sample of Italian Adults. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 714493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Nutrition Policy and Healthy China 2030 Building. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bi, X.; Gao, T.; Yang, T.; Xu, P.; Gan, Q.; Xu, J.; Cao, W.; Wang, H.; Pan, H.; et al. Effect of School-Based Nutrition and Health Education for Rural Chinese Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zeng, H.; Li, L.; Fang, Z.; Xu, L.; Shi, W.; Li, J.; Qian, J.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; et al. Personalized nutrition intervention improves nutritional status and quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors in the community: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrition 2022, 103–104, 111835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrie, G.A.; Coveney, J.; Cox, D. Exploring nutrition knowledge and the demographic variation in knowledge levels in an Australian community sample. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmugam, R.; Worsley, A. Current levels of salt knowledge: A review of the literature. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5534–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Hoefkens, C.; Verbeke, W. Chinese consumers’ understanding and use of a food nutrition label and their determinants. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroover, K.; Bucher, T.; Vandelanotte, C.; de Vries, H.; Duncan, M.J. Practical Nutrition Knowledge Mediates the Relationship Between Sociodemographic Characteristics and Diet Quality in Adults: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2020, 34, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zeng, Q.; Jin, S.; Cheng, G. The impact of changes in dietary knowledge on adult overweight and obesity in China. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, A.A.; Winham, D.M.; Heer, M.M.; Shelley, M.C., 2nd; Hutchins, A.M. Health Belief Model Predicts Likelihood of Eating Nutrient-Rich Foods among U.S. Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, D.J.; Hagger, M.S.; Hamilton, K. Predicting limiting ‘free sugar’ consumption using an integrated model of health behavior. Appetite 2020, 150, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Yan, L.; Cai, X.; Tang, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, B.; Wu, J.; et al. Associations Between Salt-Restriction Spoons and Long-Term Changes in Urinary Na(+)/K(+) Ratios and Blood Pressure: Findings From a Population-Based Cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Rowan, M.; Gadhoke, P. Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Shi, M.; He, Z.; Hao, L.; Wu, X. Association between Nutrition and Health Knowledge and Multiple Chronic Diseases: A Large Cross-Sectional Study in Wuhan, China. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández, L.; Martínez-Arnau, F.M.; Pérez-Ros, P.; Drehmer, E.; Pablos, A. Improved Nutritional Knowledge in the Obese Adult Population Modifies Eating Habits and Serum and Anthropometric Markers. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, L.D.; Goidel, K.; Bergeron, C.D.; Smith, M.L. Web-Based Health Information Seeking Among African American and Hispanic Men Living With Chronic Conditions: Cross-sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsutake, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Otsuki, A.; Umezawa, J.; Yaguchi-Saito, A.; Saito, J.; Fujimori, M.; Shimazu, T. Chronic Diseases and Sociodemographic Characteristics Associated With Online Health Information Seeking and Using Social Networking Sites: Nationally Representative Cross-sectional Survey in Japan. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e44741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Yin, P.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 394, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Samples, n (%) * | Score † | Awareness Rate § | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p-Value | %(95% CI) | p-Value | ||

| Overall | 68,673 (100.0) | 16.43 ± 4.17 | 49.3 (47.0, 51.6) | ||

| Gender | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 33,746 (51.2) | 16.31 ± 4.14 | 47.8 (45.4, 50.3) | ||

| Female | 34,927 (48.8) | 16.56 ± 4.19 | 50.8 (48.5, 53.1) | ||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 18–29 | 11,282 (21.2) | 16.74 ± 4.07 ab | 52.0 (49.7, 54.3) ab | ||

| 30–39 | 18,560 (24.0) | 16.78 ± 3.99 a | 52.5 (50.2, 54.8) a | ||

| 40–49 | 14,445 (22.3) | 16.49 ± 4.17 b | 50.0 (47.2, 52.8) b | ||

| 50–59 | 16,666 (24.4) | 16.03 ± 4.27 | 45.7 (42.7, 48.7) | ||

| 60–64 | 7720(8.2) | 15.63 ± 4.40 | 41.8 (38.4, 45.2) | ||

| Education | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Primary school or below | 12,504 (14.0) | 15.37 ± 4.39 | 39.6 (37.1, 42.2) | ||

| Junior high school | 24,012 (29.8) | 15.91 ± 4.21 | 44.3 (41.7, 46.8) | ||

| Senior high school | 13,116 (20.8) | 16.41 ± 4.12 | 48.8 (45.9, 51.8) | ||

| Junior college | 10,654 (18.4) | 17.01 ± 3.97 | 54.4 (51.4, 57.5) | ||

| Bachelor degree or above | 8373 (17.0) | 17.59 ± 3.76 | 61.0 (57.9, 64.0) | ||

| Ptrend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Occupation | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Medical institutions | 6109 (11.0) | 17.30 ± 4.02 | 58.9 (55.6, 62.2) | ||

| Education institutions | 2372 (4.1) | 16.53 ± 4.46 a | 52.0 (46.4, 57.7) a | ||

| Food industries | 5229 (7.8) | 15.65 ± 4.43 | 43.3 (38.3, 48.3) b | ||

| Others | 54,963 (77.1) | 16.38 ± 4.12 a | 48.4 (46.3, 50.4) ab | ||

| Marital | 0.083 | 0.097 | |||

| Unmarried | 8532 (15.1) | 16.61 ± 4.14 | 51.3 (48.1, 54.5) | ||

| Married | 56,838 (81.2) | 16.42 ± 4.15 | 49.0 (46.7, 51.4) | ||

| Divorced or Widowed | 3263 (3.6) | 15.74 ± 4.65 | 45.0 (38.7, 51.3) | ||

| Weight status | 0.714 | 0.573 | |||

| Underweight | 2839 (4.1) | 16.49 ± 4.24 | 47.6 (43.1, 52.0) | ||

| Normal | 37,839 (55.1) | 16.41 ± 4.16 | 49.6 (46.7, 52.5) | ||

| Overweight | 22,236 (32.4) | 16.42 ± 4.17 | 48.7 (46.6, 50.7) | ||

| Obesity | 5736 (8.4) | 16.57 ± 4.10 | 50.5 (47.7, 53.3) | ||

| Income level | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 24,053 (30.3) | 15.89 ± 4.18 a | 43.8 (41.0, 46.7) | ||

| Medium | 22,228 (29.5) | 16.32 ± 4.29 a | 49.0 (46.2, 51.7) | ||

| High | 22,392 (40.3) | 16.91 ± 4.00 | 53.6 (50.4, 56.7) | ||

| Ptrend | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Residence | <0.001 | 0.004 | |||

| Urban | 34,074 (67.0) | 16.75 ± 4.03 | 52.2 (49.3, 55.1) | ||

| Rural | 34,599 (33.0) | 15.77 ± 4.35 | 43.4 (40.5, 46.3) | ||

| Region | 0.007 | 0.023 | |||

| Eastern | 25,226 (36.7) | 16.91 ± 4.01 | 53.1 (50.1, 56.1) | ||

| Central | 21,978 (32.0) | 15.85 ± 4.44 a | 45.8 (40.2, 51.5) a | ||

| Western | 21,469 (31.3) | 16.33 ± 3.99 a | 47.3 (44.1, 50.5) a | ||

| Items | Full Score | Score (Mean ± SD) | Accurate Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| There is no harm in eating more oil, salt and added sugar. | 2 | 1.81 ± 0.59 | 90.51 |

| The association of excessive salt intake with the risk of hypertension. | 2 | 1.74 ± 0.67 | 87.08 |

| The association of excessive cooking oil intake with the risk of obesity. | 2 | 1.74 ± 0.67 | 86.96 |

| The association of drinking excessive sugary drinks with the risk of obesity and dental caries. | 2 | 1.63 ± 0.78 | 81.36 |

| Recommendation for the intake levels of foods or beverages with added sugar. | 2 | 1.38 ± 0.93 | 69.00 |

| The association of less processed meat products with the risk of cancer. | 2 | 1.35 ± 0.94 | 67.70 |

| The association of excessive animal fat with the risk of strokes. | 2 | 1.28 ± 0.96 | 63.95 |

| Recommendation for the intake levels of processed meat products. | 2 | 1.28 ± 0.96 | 63.84 |

| The recommended daily intake of added sugar. | 2 | 1.24 ± 0.97 | 62.02 |

| Foods that contain more cooking oil and salt. | 2 | 1.18 ± 0.98 | 58.84 |

| The recommended daily intake of salt. | 2 | 1.18 ± 0.98 | 58.81 |

| The recommended daily intake of cooking oil. | 2 | 0.63 ± 0.93 | 31.40 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Three Reductions” knowledge level (ref: Low) | |||

| Medium | 0.84 (0.80, 0.88) ** | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.95 (0.90, 1.00) * |

| High | 0.75 (0.70, 0.79) ** | 0.91 (0.85, 0.96) ** | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) ** |

| Gender (ref: male) | |||

| Female | 0.85 (0.81, 0.88) * | 0.84 (0.81, 0.88) ** | |

| Age (years) (ref: 18–29) | |||

| 30–39 | 1.53 (1.35, 1.70) ** | 1.49 (1.32, 1.66) ** | |

| 40–49 | 3.33 (2.96, 3.71) ** | 3.21(2.85, 3.57) ** | |

| 50–59 | 8.24 (7.34, 9.16) * | 7.79 (6.92, 8.65) ** | |

| 60–64 | 12.17 (10.76, 13.59) ** | 11.41 (10.07, 12.74) ** | |

| Education (ref: Primary School or Below) | |||

| Junior high school | 0.84 (0.78, 0.88) * | 0.81 (0.77, 0.86) ** | |

| Senior high school | 0.92 (0.85, 0.98) * | 0.84 (0.78, 0.90) ** | |

| Junior college | 0.74 (0.68, 0.81) * | 0.67 (0.61, 0.73) ** | |

| Bachelor degree or above | 0.70 (0.63, 0.77) * | 0.62 (0.55, 0.68) * | |

| Occupation (ref: others) | |||

| Food and restaurant industries | 1.27 (1.09, 1.46) * | 1.15 (0.96, 1.34) | |

| Education institutions | 0.93 (0.79, 0.94) * | 0.91 (0.80, 1.01) | |

| Medical and health institutions | 0.87 (0.79, 0.94) * | 0.87 (0.79, 0.94) ** | |

| Marital (ref: Unmarried) | |||

| Married | 1.34 (1.21, 1.48) * | 1.36 (1.22, 1.50) ** | |

| Divorced or Widowed | 2.26 (1.96, 2.56) * | 2.26 (1.96, 2.56) ** | |

| Weight status (ref: Underweight) | |||

| Normal | 0.83 (0.73, 0.93) ** | 0.82 (0.72, 0.93) * | |

| Overweight | 1.32 (1.16, 1.49) * | 1.31 (1.15, 1.48) ** | |

| Obesity | 2.32 (2.00, 2.63) ** | 2.31 (2.00, 2.62) ** | |

| Income level (ref: Low) | |||

| Medium | 0.87 (0.83, 0.92) ** | 0.83 (0.79, 0.88) * | |

| High | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91) ** | 0.78 (0.73, 0.82) * | |

| Residence (ref: rural) | |||

| Urban | 1.33 (1.26, 1.40) * | ||

| Region (ref: western) | |||

| Central | 0.31 (0.31, 0.32) * | ||

| Eastern | 0.91 (0.90, 0.91) * | ||

| Urbanization rate (ref: low) | |||

| Medium | 0.77 (0.52, 1.01) | ||

| High | 0.87 (0.55, 1.18) | ||

| GDP (ref: low) | |||

| Medium | 0.75 (0.54, 0.96) * | ||

| High | 0.60 (0.41, 0.80) * | ||

| Per capita health expenditure (ref: low) | |||

| Medium | 1.42 (0.91, 1.92) | ||

| High | 1.65 (1.08, 2.21) * |

| “Three Reductions” Knowledge Level (Ref: Low) | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Medium | 0.99 | 0.92, 1.07 | 0.831 |

| High | 0.94 | 0.86, 1.02 | 0.125 | |

| Female | Medium | 0.91 | 0.84, 0.98 | 0.018 |

| High | 0.86 | 0.79, 0.94 | 0.002 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–39 | Medium | 0.78 | 0.68, 0.87 | <0.001 |

| High | 0.74 | 0.64, 0.84 | <0.001 | |

| 40–59 | Medium | 0.95 | 0.89, 1.02 | 0.174 |

| High | 0.88 | 0.81, 0.95 | 0.002 | |

| 60–64 | Medium | 1.07 | 0.94, 1.20 | 0.241 |

| High | 1.09 | 0.94, 1.25 | 0.203 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, Y.; Ding, C.; Yuan, F.; Gong, W.; Yu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, A. Knowledge of Salt, Oil, and Sugar Reduction (“Three Reductions”) and Its Association with Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases in Chinese Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172766

Qiu Y, Ding C, Yuan F, Gong W, Yu T, Zhang Y, Liu A. Knowledge of Salt, Oil, and Sugar Reduction (“Three Reductions”) and Its Association with Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases in Chinese Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(17):2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172766

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Yujie, Caicui Ding, Fan Yuan, Weiyan Gong, Tanchun Yu, Yan Zhang, and Ailing Liu. 2025. "Knowledge of Salt, Oil, and Sugar Reduction (“Three Reductions”) and Its Association with Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases in Chinese Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 17, no. 17: 2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172766

APA StyleQiu, Y., Ding, C., Yuan, F., Gong, W., Yu, T., Zhang, Y., & Liu, A. (2025). Knowledge of Salt, Oil, and Sugar Reduction (“Three Reductions”) and Its Association with Nutrition-Related Chronic Diseases in Chinese Adults: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 17(17), 2766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17172766