Association Between the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and High-Caffeine Drinks and Self-Reported Mental Health Conditions Among Korean Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Consumption of SSBs and High-Caffeine Drinks

2.3. General Characteristics and Health-Related Behaviors

2.4. Mental Health Conditions

2.5. Statistical Analyses

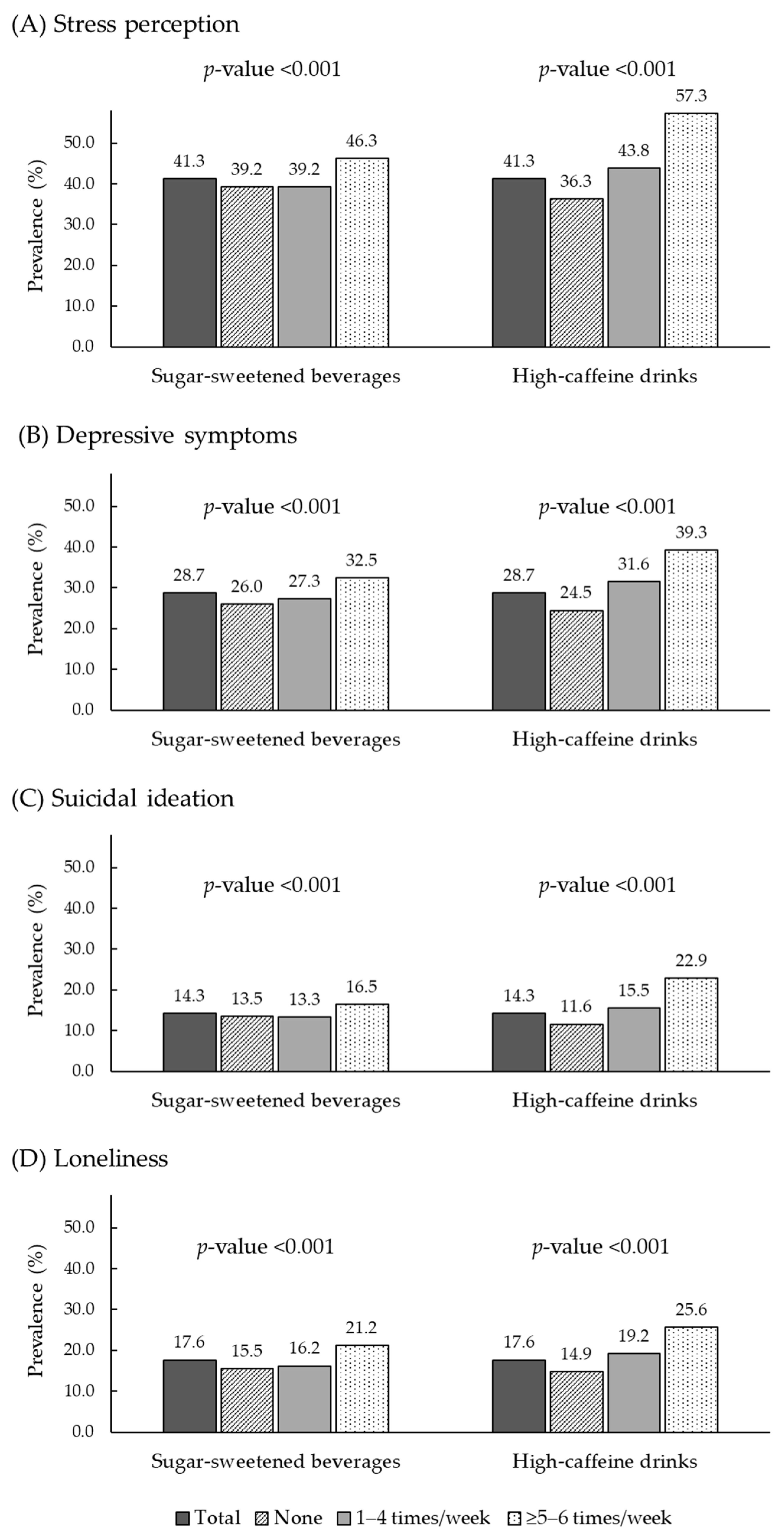

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSB | Sugar-sweetened beverage |

| KYRBS | Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey |

| KDCA | Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency |

| AOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

References

- Hargreaves, D.; Mates, E.; Menon, P.; Alderman, H.; Devakumar, D.; Fawzi, W.; Greenfield, G.; Hammoudeh, W.; He, S.; Lahiri, A. Strategies and interventions for healthy adolescent growth, nutrition, and development. Lancet 2022, 399, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J.; Mills, K.L. Is adolescence a sensitive period for sociocultural processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalsgaard, S.; McGrath, J.; Østergaard, S.D.; Wray, N.R.; Pedersen, C.B.; Mortensen, P.B.; Petersen, L. Association of mental disorder in childhood and adolescence with subsequent educational achievement. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Jia, R.; Wang, Y.; Qian, S.; Xu, Y. Mental health problems and associated school interpersonal relationships among adolescents in China: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Cohen, P.; Kasen, S.; Johnson, J.G.; Berenson, K.; Gordon, K. Impact of adolescent mental disorders and physical illnesses on quality of life 17 years later. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2006, 160, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents Surge Over Five Years… Suicide Rates Hit Record High. Available online: https://www.ncmh.go.kr/ncmh/board/commonView.do?no=4707&fno=16&depart=&menu_cd=01_04_00_01&bn=newsView&search_item=&search_content=&pageIndex=1 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Kim, T.-H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Lee, H.-H.; Park, Y. Associations between dietary pattern and depression in Korean adolescent girls. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015, 28, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Ryu, H.K. Analysis of the association between generalized anxiety disorder and dietary behaviors in adolescents: Data from the 17th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Korean J. Community Living Sci. 2023, 34, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-H. Effects of watching Mukbang and Cookbang videos on adolescents’ dietary habits and mental health: Cross-sectional study using the 18th Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2024, 29, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Shin, D. Association of eating alone behaviors with mental health conditions in Korean adolescents: Data from the 2015–2019 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2023, 38, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S.; Oh, K. Trends in dietary behavior of Korean adolescents: Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2013–2022. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2024, 37, 1563–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, H.; Tateya, S.; Tamori, Y.; Kotani, K.; Hiasa, K.I.; Kitazawa, R.; Kitazawa, S.; Miyachi, H.; Maeda, S.; Egashira, K. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1494–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-García, M.I.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Martín-Moreno, J.M.; Razquin, C.; Cervantes, S.; Guillén-Grima, F.; Toledo, E. Sugar-sweetened and artificially-sweetened beverages and changes in cognitive function in the SUN project. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, G.; Smith, A.P. A review of energy drinks and mental health, with a focus on stress, anxiety, and depression. J. Caffeine Res. 2016, 6, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, A.; Maiese, A.; Lazzari, J.; Casula, C.; Turillazzi, E.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. The dark side of energy drinks: A comprehensive review of their impact on the human body. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Temple, J.L. Relationships among soda and energy drink consumption, substance use, mental health and risk-taking behavior in adolescents. Children 2024, 11, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Gili, M.; Visser, M.; Penninx, B.W.; Brouwer, I.A.; Montaño, J.J.; Pérez-Ara, M.Á.; García-Toro, M.; Watkins, E.; Owens, M.; et al. Soft drinks and symptoms of depression and anxiety in overweight subjects: A longitudinal analysis of a European cohort. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, T.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y.; Ma, T.; Gao, D.; Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages and depressive and social anxiety symptoms among children and adolescents aged 7–17 years, stratified by body composition. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 888671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masengo, L.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Chaput, J.P.; Hamilton, H.A.; Colman, I. Energy drink consumption, psychological distress, and suicidality among middle and high school students. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 268, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivusilta, L.K.; Kuoppamäki, H.; Rimpelä, A. Energy drink consumption, health complaints and late bedtime among young adolescents. Int. J. Public Health 2016, 61, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.E.; Chew, N.S.M.; Loke, S.; Tan, J.Y.; Phee, S.; Lee, A.R.Y.B.; Ho, C.S.H. Association of coffee and energy drink intake with suicide attempts and suicide ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba-Garrido, J.; Momberg-Villanueva, D.; Rezende-Brito de Oliveira, T.; Riquelme-Pedraza, M.; Valeria-González, J.; Aguayo-Verdugo, N. Effect of energy drinks on the mental health of adolescents and young people: Systematic review. Sanus 2024, 9, 438. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Maldonado, P.; Arias-Rico, J.; Romero-Palencia, A.; Román-Gutiérrez, A.D.; Ojeda-Ramírez, D.; Ramírez-Moreno, E. Consumption patterns of energy drinks in adolescents and their effects on behavior and mental health: A systematic review. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2022, 60, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, W. Sugar-sweetened beverages consumption and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasser, E.K.; Miles-Chan, J.L.; Charrière, N.; Loonam, C.R.; Dulloo, A.G.; Montani, J.-P. Energy drinks and their impact on the cardiovascular system: Potential mechanisms. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narain, A.; Kwok, C.S.; Mamas, M.A. Soft drink intake and the risk of metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Prac. 2017, 71, e12927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.; Kim, S.-A.; Ha, J.; Lim, K. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in relation to obesity and metabolic syndrome among Korean adults: A cross-sectional study from the 2012–2016 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Nutrients 2018, 10, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Zhu, Y.; Malik, V.; Li, X.; Peng, X.; Zhang, F.F.; Shan, Z.; Liu, L. Intake of sugar-sweetened and low-calorie sweetened beverages and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freije, S.L.; Senter, C.C.; Avery, A.D.; Hawes, S.E.; Jones-Smith, J.C. Association between consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juice with poor mental health among US adults in 11 US States and the District of Columbia. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, G.; Micek, A.; Castellano, S.; Pajak, A.; Galvano, F. Coffee, tea, caffeine and risk of depression: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education; Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. User Guide for the Korean Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2005–2023. Available online: https://www.kdca.go.kr/yhs/yhs/main.do (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Park, S.; Khang, Y.; Oh, K. Data resource profile: The Korea Youth Risk Behavior web-based Survey (KYRBS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yun, S.; Hwang, S.S.; Shim, J.O.; Chae, H.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.C.; Lim, D.; Yang, S.W.; et al. The 2017 Korean National Growth Charts for children and adolescents: Development, improvement, and prospects. Korean J. Pediatr. 2018, 61, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, J.S.; Cho, Y.H. Depression moderates the relationship between body image and health-related quality of life in adolescent girls. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Choi, Y.J. Association of school, family, and mental health characteristics with suicidal ideation among Korean adolescents. Res. Nurs. Health 2015, 38, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Hu, F.B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yan, N.; Jiang, H.; Cui, M.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Mi, B.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Fan, Y. Consumption of sugar sweetened beverages, artificially sweetened beverages and fruit juices and risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: A meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1019534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.; Bucher Della Torre, S. Sugar-sweetened beverages and obesity among children and adolescents: A review of systematic literature reviews. Child Obes. 2015, 11, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.K.; Chung, Y.; Chang, Y.; Oh, C.-M.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Jung, J.Y. Longitudinal analysis for the risk of depression according to the consumption of sugar-sweetened carbonated beverage in non-diabetic and diabetic population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Park, Y.; Freedman, N.D.; Sinha, R.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Blair, A.; Chen, H. Sweetened beverages, coffee, and tea and depression risk among older US adults. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, H.; Sheng, B.; Zhou, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Consumption of sugary beverages, genetic predisposition and the risk of depression: A prospective cohort study. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 37, e101446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, L.; Stubbs, B.; Koyanagi, A. Consumption of carbonated soft drinks and suicide attempts among 105,061 adolescents aged 12–15 years from 6 high-income, 22 middle-income, and 4 low-income countries. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Guo, J.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, R.; Xu, H.; Ding, P.; Tao, F. Association between screen time, fast foods, sugar-sweetened beverages and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-H.; Park, S.K.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Oh, C.-M.; Mansur, R.B.; Alfonsi, J.E.; Cha, D.S.; Lee, Y.; McIntyre, R.S.; Jung, J.Y. The association between insulin resistance and depression in the Korean general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 208, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koponen, H.; Kautiainen, H.; Leppänen, E.; Mäntyselkä, P.; Vanhala, M. Association between suicidal behaviour and impaired glucose metabolism in depressive disorders. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrell, C.S.; Burgado, J.; Kelly, S.D.; Johnson, Z.P.; Neigh, G.N. High-fructose diet during periadolescent development increases depressive-like behavior and remodels the hypothalamic transcriptome in male rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 62, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, B.-J. Definition and control of anxiety and fear. J. Korean Dent. Soc. Anesthesiol. 2007, 7, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kische, H.; Ollmann, T.M.; Voss, C.; Hoyer, J.; Rückert, F.; Pieper, L.; Kirschbaum, C.; Beesdo-Baum, K. Associations of saliva cortisol and hair cortisol with generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and major depressive disorder: An epidemiological cohort study in adolescents and young adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 126, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruessner, J.C.; Dedovic, K.; Khalili-Mahani, N.; Engert, V.; Pruessner, M.; Buss, C.; Renwick, R.; Dagher, A.; Meaney, M.J.; Lupien, S. Deactivation of the limbic system during acute psychosocial stress: Evidence from positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, S.; Duman, R.; Sanacora, G. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor, depression, and antidepressant medications: Meta-analyses and implications. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 64, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molteni, R.; Barnard, R.; Ying, Z.; Roberts, C.K.; Gómez-Pinilla, F. A high-fat, refined sugar diet reduces hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neuronal plasticity, and learning. Neuroscience 2002, 112, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainey, S.J.; Kwakwa, K.A.; Bray, J.K.; Pillote, M.M.; Tir, V.L.; Towers, A.E.; Freund, G.G. Short-term high-fat diet (HFD) induced anxiety-like behaviors and cognitive impairment are improved with treatment by glyburide. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Sim, S.; Choi, H.G. High stress, lack of sleep, low school performance, and suicide attempts are associated with high energy drink intake in adolescents. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utter, J.; Denny, S.; Teevale, T.; Sheridan, J. Energy drink consumption among New Zealand adolescents: Associations with mental health, health risk behaviours and body size. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2018, 54, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Limit Adults to 4 Cups of Coffee a Day, Teens to 2 Cans of Energy Drinks. Available online: https://www.mfds.go.kr/brd/m_99/down.do?brd_id=ntc0021&seq=44023&data_tp=A&file_seq=1 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Shearer, J. Methodological and metabolic considerations in the study of caffeine-containing energy drinks. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibo, C.; Van Griethuysen, A.; Visram, S.; Lake, A. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: A systematic review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. Public Health 2024, 227, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Rehman, H.; Babayan, Z.; Stapleton, D.; Joshi, D.-D. Energy drinks and their adverse health effects: A systematic review of the current evidence. Postgrad. Med. 2015, 127, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.D.; Scherr, R.E. Risk of energy drink consumption to adolescent health. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 13, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, G.S.; Hurworth, M.; Jacoby, P.; Maddison, K.; Allen, K.; Martin, K.; Christian, H.; Ambrosini, G.L.; Oddy, W.; Eastwood, P.R. Energy drink intake is associated with insomnia and decreased daytime functioning in young adult females. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1328–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, C.K.; Prichard, J.R. Demographics, health, and risk behaviors of young adults who drink energy drinks and coffee beverages. J. Caffeine Res. 2016, 6, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.M.; Sadeh, A. Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Paksarian, D.; Lamers, F.; Hickie, I.B.; He, J.; Merikangas, K.R. Sleep patterns and mental health correlates in US adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2017, 182, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouja, C.; Kneale, D.; Brunton, G.; Raine, G.; Stansfield, C.; Sowden, A.; Sutcliffe, K.; Thomas, J. Consumption and effects of caffeinated energy drinks in young people: An overview of systematic reviews and secondary analysis of UK data to inform policy. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keast, R.S.; Swinburn, B.A.; Sayompark, D.; Whitelock, S.; Riddell, L.J. Caffeine increases sugar-sweetened beverage consumption in a free-living population: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penolazzi, B.; Natale, V.; Leone, L.; Russo, P.M. Individual differences affecting caffeine intake. Analysis of consumption behaviours for different times of day and caffeine sources. Appetite 2012, 58, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, I.; Landolt, H.P. Coffee, caffeine, and sleep: A systematic review of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 31, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Mei, H.; Shi, D.; Wang, X.; Cheng, M.; Fan, L.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, R.; Wang, B.; Yang, M. Association of caffeine and caffeine metabolites with obesity among children and adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009–2014. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 57618–57628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.-J.; Kim, W.-H. Converged influence of the academic stress recognized by teenagers on mental health: Mediating effect of parent-child communication. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2017, 8, 283–293. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.R. The relationship between high school seniors’ experience of daily life activities and levels of depression. Korean J. Child Stud. 1995, 16, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Yang, S.; Park, S. Path analysis of suicidal attempts among adolescents with suicidal thoughts: Comparison between middle and high school students. J. Korean Soc. Wellness 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total n (Wt’d %) |

|---|---|

| Total | 51,850 (100.00) |

| Consumption frequency of SSBs | |

| None | 3427 (6.56) |

| 1–4 times/week | 33,245 (63.84) |

| ≥5–6 times/week | 15,178 (29.60) |

| Consumption frequency of high-caffeine drinks | |

| None | 26,876 (51.30) |

| 1–4 times/week | 19,892 (38.53) |

| ≥5–6 times/week | 5082 (10.17) |

| Sex | |

| Boys | 26,397 (51.56) |

| Girls | 25,453 (48.44) |

| Age | 15.20 ± 0.03 |

| School level | |

| Middle school | 28,015 (51.64) |

| High school | 23,835 (48.36) |

| Residential area | |

| Metropolitan | 22,212 (41.54) |

| Small- to medium-sized city | 25,814 (52.88) |

| Rural | 3824 (5.58) |

| Household economic status | |

| Low | 5816 (10.71) |

| Middle | 24,146 (46.01) |

| High | 21,888 (43.28) |

| Subjective academic performance | |

| Low | 16,313 (31.18) |

| Middle | 15,484 (30.02) |

| High | 20,053 (38.80) |

| Variable | Sugar-Sweetened Beverages | High-Caffeine Drinks |

|---|---|---|

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||

| Boys | 1.44 (1.38–1.51) (1) | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) |

| Girls | Ref. | Ref. |

| School level | ||

| Middle school | Ref. | Ref. |

| High school | 1.13 (1.07–1.19) | 1.56 (1.44–1.69) |

| Residential area | ||

| Metropolitan | 1.18 (1.07–1.31) | 1.37 (1.17–1.60) |

| Small- to medium-sized city | 1.18 (1.06–1.30) | 1.32 (1.14–1.54) |

| Rural | Ref. | Ref. |

| Household economic status | ||

| Low | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) |

| Middle | 0.96 (0.92–1.00) | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) |

| High | Ref. | Ref. |

| Residential status | ||

| Living with family | Ref. | Ref. |

| Not living with family | 1.05 (0.95–1.17) | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) |

| Subjective academic performance | ||

| Low | 1.10 (1.05–1.17) | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) |

| Middle | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) | 0.93 (0.86–1.01) |

| High | Ref. | Ref. |

| Sleep duration | ||

| Less than 5 h | 1.48 (1.38–1.59) | 3.47 (3.10–3.89) |

| 5–6 h | 1.30 (1.22–1.39) | 2.56 (2.29–2.86) |

| 6–7 h | 1.11 (1.05–1.19) | 1.56 (1.41–1.73) |

| 7–8 h | 1.07 (1.00–1.13) | 1.16 (1.04–1.30) |

| More than 8 h | Ref. | Ref. |

| Current smoking | ||

| Yes | 1.43 (1.29–1.59) | 1.70 (1.49–1.94) |

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Current drinking | ||

| Yes | 1.30 (1.21–1.39) | 1.53 (1.39–1.68) |

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Weight status | ||

| Underweight | 0.94 (0.86–1.04) | 1.08 (0.96–1.22) |

| Normal weight | Ref. | Ref. |

| Overweight | 1.21 (1.13–1.30) | 1.19 (1.07–1.32) |

| Obesity | 1.36 (1.23–1.49) | 1.20 (1.08–1.34) |

| Regular physical activity | ||

| Yes | Ref. | Ref. |

| No | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | 1.10 (1.03–1.18) |

| Breakfast skipping | ||

| Yes | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | 1.22 (1.14–1.30) |

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Adequate water intake | ||

| Yes | Ref. | Ref. |

| No | 1.30 (1.24–1.36) | 1.12 (1.04–1.20) |

| Nutritional education | ||

| Yes | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) |

| No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Total (n = 51,850) | Middle School (n = 28,015) | High School (n = 23,835) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1–4 Times/Week | ≥5–6 Times/Week | p-Value | None | 1–4 Times/Week | ≥5–6 Times/Week | p-Value | None | 1–4 Times/Week | ≥5–6 Times/Week | p-Value | |

| (n = 3427) | (n = 33,245) | (n = 15,178) | (n = 1954) | (n = 18,464) | (n = 7597) | (n = 1473) | (n = 14,781) | (n = 7581) | ||||

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |||||||

| Stress Perception | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) (1) | 1.35 (1.24–1.46) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 1.25 (1.12–1.41) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.93–1.18) | 1.43 (1.27–1.60) | <0.0001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.00 | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | 1.32 (1.19–1.46) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) | 1.26 (1.09–1.46) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.13 (0.99–1.29) | 1.38 (1.20–1.59) | <0.0001 |

| Suicidal ideation | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.86–1.09) | 1.23 (1.09–1.39) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 1.15 (0.98–1.35) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 1.33 (1.09–1.62) | <0.0001 |

| Loneliness | 1.00 | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) | 1.44 (1.28–1.61) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.83–1.10) | 1.31 (1.13–1.53) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.16 (0.99–1.37) | 1.61 (1.36–1.91) | <0.0001 |

| Total (n = 51,850) | Middle School (n = 28,015) | High School (n = 23,835) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1–4 Times/Week | ≥5–6 Times/Week | p-Value | None | 1–4 Times/Week | ≥5–6 Times/Week | p-Value | None | 1–4 Times/Week | ≥5–6 Times/Week | p-Value | |

| (n = 26,876) | (n = 19,892) | (n = 5082) | (n = 16,192) | (n = 9869) | (n = 1954) | (n = 10,684) | (n = 10,023) | (n = 3128) | ||||

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |||||||

| Stress Perception | 1.00 | 1.30 (1.25–1.36) (1) | 2.13 (1.99–2.29) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.35 (1.27–1.43) | 2.35 (2.12–2.60) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.23 (1.16–1.31) | 1.96 (1.78–2.15) | <0.0001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.00 | 1.32 (1.26–1.38) | 1.75 (1.62–1.88) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.41 (1.32–1.52) | 1.91 (1.70–2.16) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | 1.58 (1.44–1.73) | <0.0001 |

| Suicidal ideation | 1.00 | 1.32 (1.24–1.41) | 2.04 (1.86–2.24) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.38 (1.26–1.51) | 2.42 (2.12–2.76) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.24 (1.13–1.35) | 1.74 (1.54–1.98) | <0.0001 |

| Loneliness | 1.00 | 1.27 (1.20–1.35) | 1.72 (1.59–1.87) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.36 (1.25–1.48) | 2.06 (1.84–2.32) | <0.0001 | 1.00 | 1.18 (1.08–1.27) | 1.50 (1.34–1.68) | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.J.; Na, Y.; Lee, K.W. Association Between the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and High-Caffeine Drinks and Self-Reported Mental Health Conditions Among Korean Adolescents. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162652

Lee SJ, Na Y, Lee KW. Association Between the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and High-Caffeine Drinks and Self-Reported Mental Health Conditions Among Korean Adolescents. Nutrients. 2025; 17(16):2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162652

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Seung Jae, Yeseul Na, and Kyung Won Lee. 2025. "Association Between the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and High-Caffeine Drinks and Self-Reported Mental Health Conditions Among Korean Adolescents" Nutrients 17, no. 16: 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162652

APA StyleLee, S. J., Na, Y., & Lee, K. W. (2025). Association Between the Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and High-Caffeine Drinks and Self-Reported Mental Health Conditions Among Korean Adolescents. Nutrients, 17(16), 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17162652