Abstract

Background/Objectives: Digital interventions can have a positive effect on the health-related behaviors of adolescents. However, it is unclear if social network-based interventions using Facebook can help to optimize medical treatment as usual (TAU) for adolescent obesity in public health care centers. We examined the feasibility, usability, and effectiveness of APOLO-Teens, a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Facebook-based intervention as a supplement to TAU on changing eating habits/behaviors, physical activity levels, and psychological functioning of adolescents with overweight/obesity. Methods: This was a Randomized Controlled Trial (Trial registration number: NCT04642222). One-hundred and thirty-five adolescents aged 13 to 18 years (67.5% females) were randomly assigned to the TAU control group (n = 66) and the APOLO-Teens intervention group (n = 69). Intervention outcomes were measured at baseline and the end of the intervention (6 months later). Using per-protocol analysis, the sample size retained for final analysis included 77 participants (Control group = 39; Intervention group = 38). Two-way mixed ANOVAs were used to test within-and between-group changes. Results: The APOLO-Teens social network-based intervention was feasible (adherence rate: 85.5%) and the intervention group had a significant increase in fruit consumption (F (1,35) = 6.99, p = 0.012; significant group-by-time interaction). Both groups increased vegetables on the plate consumption and decreased pastries/cakes intake, depressive symptomatology, grazing eating pattern, and BMI z-score (p < 0.05; significant time interaction). Conclusions: The APOLO-Teens social network-based intervention was feasible, and the effectiveness results suggest that it can be a beneficial supplementary intervention to TAU in adolescent obesity.

1. Introduction

Obesity in adolescence is related to short- and long-term physical and psychological consequences and is also a risk factor for obesity in adulthood [1,2]. Some of the consequences of having excessive weight in adolescence include metabolic and cardiovascular disorders (e.g., development of metabolic syndrome), poor academic performance, depression, increased risk for developing disordered eating behaviors, and lower quality of life [3]. Although genetic factors are related to the individual predisposition for weight gain, environmental, behavioral, and family factors can also play a significant role. Some of the behaviors that can increase the risk for obesity include the intake of high caloric foods and sweetened beverages, a reduction in fruit and vegetable consumption, and an increase in the time spent on sedentary activities [3,4,5].

Although global overweight prevalence during childhood and adolescence is projected to stabilize from 2022 to 2050, obesity rates are expected to rise markedly between 2022 and 2030, and this upward trend is expected to persist through 2050. Timely public health measures are required to mitigate this growing public health challenge [6]. Multicomponent interventions combining diet, physical activity, and behavioral therapy are the first-line treatment for adolescent overweight/obesity [3,7]. They can produce positive changes in health behaviors and appear to be more effective than single-component interventions at enhancing the health-related quality of life and at reducing body weight in adolescence [8,9,10,11].

However, these interventions are rarely offered in public health care settings, such as hospitals, due to a lack of human/economic resources, evidence-based knowledge, and counseling skills [12]. Given the rising rates of overweight and obesity among adolescents, particularly, in low-income families [1,6,13] and adolescents’ lack of motivation for lifestyles changes, alternatives are needed so that multicomponent interventions for adolescent obesity can be more easily implemented in public health care services to achieve mass dissemination [14].

Evidence suggests that social networking sites can have a positive effect on health behavior change [15,16,17]. Previous studies using Facebook® to deliver weight-loss interventions showed high feasibility and acceptability [18,19,20,21,22]. In particular, social media networks are widely used by adolescents and have the potential to reduce the high attrition rates of hospital standard treatment for overweight/obesity [22,23,24]. For example, Parks and colleagues conducted a pilot trial that showed that private Facebook groups were a feasible adjunct to improve adherence to medical weight management in youth with severe obesity [24]. However, results regarding weight loss are mixed. Some studies using Facebook-based interventions showed significant Body Mass Index (BMI) reduction in college students [25]. On the other hand, a three-arm randomized controlled trial testing a 12-week Facebook lifestyle counseling intervention with and without physical activity monitorization to adolescents with overweight/obesity in school settings showed no significant intervention effects on physical activity levels and BMI [20].

Despite promising results, the evidence on social media-based interventions in pediatric obesity remains limited. Existing studies vary widely in design, population (school vs. clinical settings), and intervention components, making it difficult to draw clear conclusions regarding their effectiveness [19,20,26,27]. Moreover, no previous studies explore the use of a Facebook-based intervention to provide Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for adolescents undergoing weight loss treatment in public hospital settings.

Therefore, this study addresses these gaps by evaluating the feasibility, usability, and effectiveness of APOLO-Teens, a manualized CBT intervention delivered via Facebook®, and a self-monitoring web application with personalized feedback, as an adjunct to standard medical/nutritional treatment as usual (TAU) [28] in a public hospital setting.

APOLO-Teens targets obesity-related behaviors and aims to promote the adoption of healthy eating habits and lifestyle behaviors. The APOLO-Teens was designed to be part of a multidisciplinary intervention for obesity that includes the medical/nutritional treatment as usual (TAU). To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial to test a manualized Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Facebook-based intervention for adolescents with overweight and obesity undergoing medical/nutritional treatment at a public hospital.

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to test the feasibility, usability, and effectiveness of the Facebook-based intervention APOLO-Teens as a supplementary intervention to optimize TAU for adolescents with overweight and obesity undergoing hospital weight loss treatment. We hypothesized that, compared to TAU alone, the APOLO-Teens intervention would lead to greater improvements in health-related behaviors (e.g., fruit intake, physical activity).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a randomized control trial with two groups: the TAU control group (TAU group) and the APOLO-Teens intervention group (APOLO-Teens group). Participants were recruited in their medical appointment in two public hospitals in the north of Portugal from October 2015 to December 2017. This study had approval from the two hospital ethical committees and the University Ethics Commission. It was registered on the ClinicalTrials.gov registry (NCT04642222).

Participants accepting participation signed an informed consent form and responded to a set of questionnaires. After completing the baseline assessment, participants were consecutively randomized using the Research Randomizer web-based program (http://www.randomizer.org/, accessed on 1 October 2015) into the APOLO-Teens group or the TAU group by a researcher not involved in data management. The allocation ratio was 1:1. Randomization was stratified by sex to keep a balanced distribution of boys and girls across groups. This study comprised online assessments at baseline (Tb) and end of intervention (Tf) (or the corresponding period for the control group). Anthropometric data was collected from the hospital clinical charts at baseline, three months after the beginning of the intervention, and at the end of the intervention. Participants in the APOLO-Teens group received the APOLO-Teens web-based intervention delivered by Facebook® in addition to their treatment as usual (TAU). APOLO-Teens intervention facilitator and participants were not blinded to the treatment group. At the end of the study, participants randomized to the control group were offered access to the intervention materials.

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

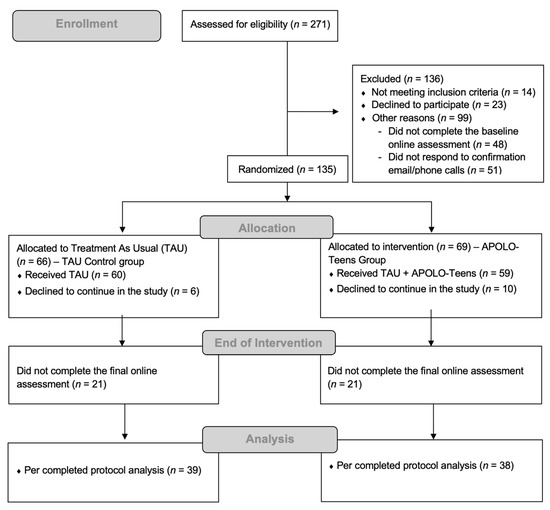

Participants were adolescents, aged between 13 and 18 years old, with overweight or obesity (BMI z-score ≥ 1 (World Health Organization) under the TAU weight loss. Adolescents were recruited directly by a psychologist at the public hospitals in the context of a previously scheduled appointment with a nutritionist/pediatrician (TAU) after parental and adolescent written consent. Inclusion criteria included having a Facebook® account and access to the Internet at least three times per week. Exclusion criteria included (1) medical conditions that affect weight; (2) specific learning difficulties that prevented adolescents from reading and understanding written text; (3) ambulatory movement limitations; (4) and BMI z-score above 4 or an indication for bariatric surgery (please see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

APOLO-Teens randomized controlled trial flow diagram.

2.3. Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire: At baseline (Tb) participants were asked about age, sex, educational level, and parents’ demographic data.

2.3.1. Primary Outcomes:

Feasibility and Usability

Feasibility: The adherence rate (the proportion of adolescents invited who participated in the intervention) and the attrition rate (proportion of adolescents who dropped out during the intervention) were estimated to evaluate the feasibility of the APOLO-Teens web-based intervention.

APOLO-Teens Usability Questionnaire: This is a 30-item questionnaire (designed by the research team) applied 3 months after the beginning of the intervention to the APOLO-Teens group. It uses a 5-point rating scale (from 0 = “nothing” to 4 = “extremely”) to evaluate the usability perception of the intervention group participants regarding the following APOLO-Teens web-based intervention domains: weekly videos/tasks, chat sessions, self-monitoring system, and overall utility/satisfaction (Please see Table 1). The higher the total score, the higher the usability.

Table 1.

APOLO-Teens feasibility and usability.

Behavioral

Foods/beverages frequency questionnaire: This questionnaire assesses the frequency of consumption of soup (1 plate), fruit (1 piece), vegetables (1/4 of the plate), sweetened beverages drinks (1 glass) and pastries/sweets (1 piece) in the previous week (0 = no intake; 1 = once a week; 2 = 2 to 4 times per week; 3 = 5 to 6 times per week; 4 = once a day; 5 = twice a day; 6 = three times a day; 7 = 4 times a day; 8 = 5 times a day; 9 = 6 or more times per day). Higher values indicate higher consumption.

Youth Activity Profile (YAP) [29]: This is a 15-item questionnaire to evaluate physical activity and sedentary behaviors in youth on the previous seven days through a 1–5 Likert scale. It generates minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week at school, out of school, and also minutes per week spent on sedentary behaviors.

2.3.2. Secondary Outcomes

Problematic Eating Behavior

Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT) [30,31]: It evaluates eating behaviors disturbance through a 26-item scale. ChEAT comprises four subscales: (1) fear of getting fat, (2) restrictive and purging behaviors, (3) food preoccupation, and (4) social pressure to eat. Higher scores indicate more eating disturbance (McDonald’s for this sample: ChEAT total score = 0.87).

Repetitive Eating Questionnaire (Rep(eat)-Q) [32]: This is 12-item self-report measure to measure grazing-type eating patterns by a Likert 7-point scale. Higher scores indicate the existence of a grazing-type eating pattern (McDonald’s for this sample = 0.83).

Psychological Functioning

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21) [33,34]: This is a 21-item instrument that generates three subscales assessing depression, anxiety, and stress. For the present study, just the depression subscale will be used, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptomology (McDonald’s for this sample = 0.85).

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory-PedsQL [35]: It is a 21-item measure assessing health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. PedsQL includes four subscales: physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and school functioning as a total score. Higher scores indicate higher health-related quality of life (McDonald’s for this sample: total score = 0.88).

BMI z-Score

BMI z-score was calculated based on weight and height registered in the hospital clinical charts from the TAU medical appointments during the intervention period (or equivalent time for the TAU control group). Weight was measured by a digital balance (Tanita® model TBF-300) and height by a portable stadiometer (Seca® model 206). BMI z-scores for age and sex were calculated by WHO Anthroplus software 3.2.2. version. Assessments conducted within 30 days of baseline, middle (3 months), and end of intervention assessments were used.

2.4. Intervention

2.4.1. Treatment As Usual (TAU)

TAU is the standard intervention offered in Portuguese public hospitals accessible at a low cost for the overall population. For this study, the TAU comprised three nutritional appointments (at baseline, 3 and 6 months after baseline). TAU 30 min appointments included a physical examination (weight, height) and personalized dietary/lifestyle recommendations regarding the frequency of healthy/unhealthy food consumption, reduction in screen time, and the increase in daily moderate to vigorous physical activity. TAU did not integrate any structured lifestyle program or psychological intervention tailored to weight loss. The TAU intervention is common to the experimental and control groups. No statistically significant differences were found between the proportion of TAU nutritional appointments between the intervention and control groups (APOLO-Teens group M = 1.6, SD = 0.7; TAU Group M = 1.9, SD = 0.8; Z = 1.42, p = 0.16).

2.4.2. APOLO-Teens Web-Based Intervention

The APOLO-Teens was designed to optimize TAU by promoting the adoption of healthy eating habits and lifestyle behaviors. Particularly, it aims to promote higher consumption of fruits and vegetables, increase physical activity levels, reduce sedentary time, enhance psychological well-being, and facilitate weight loss.

The APOLO-Teens web-based intervention comprises three main components: (1) a manualized intervention implemented via Facebook® in private groups (of 10–12 participants). The intervention includes psychoeducational weekly videos with cognitive–behavioral therapy strategies and daily psychoeducational/motivational images on 6 different monthly topics. Each topic was discussed with a set of weekly cognitive–behavioral tasks (Online Resource—Figure S1); (2) a weekly self-monitoring system (the APOLO-Teens web application) with automatic feedback messages assessing the following behaviors: hours of physical activity, sedentary time, and consumption of fruits and vegetable (Online Resource—Figure S2); and (3) monthly chat sessions (20–30 min) via Facebook Messenger® coordinated by an MSc Psychologist and available on request from the participants. This intervention was fully implemented by a psychologist with a Master’s degree trained in cognitive–behavioral therapy. A detailed description of the intervention has been published [28].

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to describe participants’ sociodemographic and anthropometric baseline characteristics. Validated self-report instruments were used to assess depressive symptoms and eating behaviors; however, no clinical cutoff scores were applied, as the analyses focused on continuous data to reflect the full spectrum of symptom severity. Chi-square tests (χ2), t-test for independent samples, and Mann–Whitney U tests were used, according to variables distributions, to test differences between the TAU group and APOLO-Teens group at baseline (Tb). We conducted logarithmic and square root transformations to our measures if the assumption of normality was violated.

Two-way mixed ANOVAs (with main effects for condition/time and interaction effects) were performed to assess differences in the patterns of change in primary and secondary outcome measures between baseline and end of intervention assessments. Partial Etas (ηp2) were reported as an estimation of the effect size (small effect = 0.01; medium effect = 0.06; and large effect = 0.14) [36].

The minimum sample size to detect a medium effect size of 0.25 (Cohen’s d) on primary outcomes considering the following assumptions: error of 5%, power of 90%, significant at alpha = 0.05, and accounting for 20% attrition was 55 adolescents (G*Power 3.1).

The goal of this preliminary study was to assess efficacy under conditions of adequate engagement; thus all analyses were conducted using a per-protocol analysis, excluding adolescents who were randomized but did not enroll in all the assessment moments. The IBM® SPSS® Statistics 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analyses. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

Figure 1 presents the flow chart of participants throughout the study. Of the 135 participants that accepted to participate in the study, 69 (51.11%) were randomized to the APOLO-Teens group and 66 (48.89%) to the TAU group. The 69 participants allocated to the APOLO-Teens group were distributed by six Facebook® private groups of about 12 participants each. A total of 42 participants (21 from the TAU group and 21 from the APOLO-Teens group) did not respond to the end of the intervention online assessment and were excluded from the final analysis. The final analytical sample included 39 participants in the TAU group and 38 participants in the APOLO-Teens group.

Participants’ demographic and anthropometric baseline characteristics are shown in Table 2 for the TAU group and the APOLO-Teens group. No differences between the two groups were found regarding sex (χ2 (1) = 1.30, p = 0.255) or age (U = 718.50, p = 0.814). Baseline differences between the TAU group and the APOLO-Teens group were explored for primary and secondary outcome measures. No differences were found, except for health-related quality of life (PedsQL) (U = 530.50, p = 0.046), which was significantly higher for TAU group at baseline (M = 79.78, SD = 15.67 vs. M=74.43, SD = 15.05).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the APOLO-Teens randomized controlled trial.

3.2. Feasibility and Usability of APOLO-Teens Web-Based Intervention

Out of the 69 participants initially included in the APOLO-Teens group, 59 stayed as members in the Facebook® private group until the end of the intervention suggesting that the APOLO-Teens intervention had a high adherence rate (85.51%) and an attrition rate of 14.49%.

At baseline assessment (Tb) all participants stated to have Internet access at home and 70.0% had a personal Facebook® account for at least 3 years. The device mostly used to access their Facebook® account was the smartphone (67.1%), and 55.7% of the participants reported using Facebook® at least once a day.

APOLO-Teens usability was evaluated by the APOLO-Teens Usability Questionnaire (Table 1). On average, participants (N = 35) rated the intervention as highly (n = 15; 42.9%) to extremely useful (n = 8; 22.9%) and a highly (n = 13; 37.1%) to extremely (n = 9; 25.7%) useful supplement to their treatment as usual. APOLO-Teens web application (used as the self-monitoring tool) was rated as highly (n = 18; 51.4%)/extremely (n = 15; 42.9%) easy to use. Participants understood the language used in videos and images on Facebook® private groups (High: n = 12; 34.3%/Extremely: n = 17; 48.6%) and found the intervention to have a significant impact on their motivation to follow medical recommendations (High: n = 12; 34.3%/Extremely: n = 8; 22.9%), highly recommending APOLO-Teens to other adolescents in the same situation (High: n = 15; 42.9%/Extremely: n = 13; 37.1%).

Over the 6-month APOLO-Teens web-based intervention, 55.26% (n = 21) of participants saw at least 12 out of the 24 weekly Facebook® psychoeducational videos (M = 12.50, SD = 7.51) and answered to a mean of 7.68 (SD = 6.23) monitoring weekly questionnaires in APOLO-Teens web application out of 24. Regarding the monthly chat sessions, nine participants (23.7%) requested at least one chat session. These participants requested on average 1.67 (SD = 0.71) chat sessions out of 6 (min.= 1; max. = 3).

3.3. Intervention Effectiveness

3.3.1. Primary Outcomes—Food/Beverages Consumption, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Time

To assess if patterns of change are different between the TAU group and APOLO-Teens group on behavioral outcomes, two-way mixed ANOVAs were conducted considering two-assessment moments: baseline (Tb) and end of intervention (Tf) (Table 3). The following behavioral outcome measures were evaluated: weekly consumption of soup, fruit, vegetables on the plate, sweetened beverages and pastries/cakes, minutes of sedentary time a day, minutes in moderate to vigorous physical activity at school and out of school.

Table 3.

Summary of two-way ANOVA results for primary outcomes.

Regarding the frequency of food and beverages consumption, an interaction effect between group condition and time was found (F (1,35) = 6.99, p = 0.012), showing different patterns of change regarding the weekly consumption of fruit between the TAU group and APOLO-Teens group. This intervention produced a large effect on fruit consumption (ηp2 = 0.166). The APOLO-Teens group showed an increase in fruit consumption between baseline and end of intervention when compared with the TAU group, who decreased fruit consumption. On average, the APOLO-Teens group increased fruit consumption from five to six times per week to consume about two pieces of fruit per day. At baseline, the estimated marginal mean of the fruit consumption was 3.84 (95% CI: 2.82–4.45) in the control group and 3.39 (95% CI: 2.25–3.84) in the intervention group. At the end of the intervention, the mean in the control group remained relatively stable at 3.52 (95% CI: 2.45–4.37), whereas the intervention group showed an increase to 4.89 (95% CI: 3.54–5.41).

No significant interaction effects were found between group condition and time for weekly consumption of vegetables, soup, sweetened beverages, and pastries/cakes. However, a main effect of time was found for weekly consumption of vegetables (F (1,35) = 6.49, p = 0.015; ηp2 = 0.157 (large effect)) and pastries/cakes (F (1,33) = 9.83, p = 0.004; ηp2 = 0.230 (large effect)), with both groups increasing their consumption of vegetables on the plate and decreasing their consumption of pastries and cakes to less than once a week.

Two-way mixed ANOVAs (Table 3) showed a main effect of time for minutes in moderate to vigorous physical activity at school (F (1,41) = 6.62, p = 0.014; ηp2 = 0.139 (medium effect)) and minutes on sedentary time a day (F (1,41) = 4.53, p = 0.039; ηp2 = 0.099 (medium effect)). No interaction effects of group condition and time were found for time in sedentary activities per day and minutes in moderate to vigorous physical activity, suggesting there were no differences between the TAU and APOLO-Teens group in physical activity levels and sedentary time.

3.3.2. Secondary Outcomes—Problematic Eating Behavior, Psychological Functioning, and BMI z-Score

No main effects of group condition or interaction effects were found for psychological functioning outcomes (depressive symptomatology, health-related quality of life) and problematic eating behavior (disturbed eating behavior, grazing eating pattern) (Table 4). Main effects of time were found for depressive symptomatology (F (1,71) = 4.29, p = 0.042; ηp2 = 0.057 (small effect)) and grazing eating pattern (F (1,70) = 11.28, p = 0.001; ηp2 = 0.139 (medium effect)), suggesting that depressive symptomatology and grazing eating type decreased in both groups between baseline and end of intervention.

Table 4.

Summary of two-way ANOVA results for secondary outcomes.

Patterns of change in BMI z-score across APOLO-Teens intervention were analyzed considering anthropometric data in clinical charts for baseline and end of intervention (Table 4). There was a significant effect of time on BMI z-score (F (1,62) = 8.14, p = 0.006; ηp2 = 0.116 (medium effect)), with BMI z-score decreasing in both groups. No interaction effect between group condition and time was found.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate the feasibility and usability of a web-based intervention using Facebook to optimize the treatment as usual for adolescents with overweight/obesity undertreatment in public health care centers. Despite the expected high attrition in e-health trials [37,38], 87.1% of the participants completed the web-based intervention, reporting high usability and satisfaction with the several APOLO-Teens components (Facebook® private group/weekly tasks, self-monitoring system with automatic feedback messages, and chat).

The standard treatment offered at low cost in public health care centers for pediatric obesity can be the first step to reducing the gap in specialized treatment access between high and low socioeconomic status. The addition of an attractive web-based CBT-based intervention to standard treatment can result, to some extent, in more favorable outcomes with low costs. Effectiveness analysis showed that the APOLO-Teens web-based intervention was superior to the standard treatment for promoting fruit consumption (group-by-time interaction effect). Over time, both groups increased their vegetable intake and decreased their consumption of pastries and cakes, time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity at school, depressive symptoms, grazing eating patterns, and BMI z-scores. However, no significant group-by-time interaction effects were observed.

The APOLO-Teens web-based intervention was able to significantly increase fruit consumption from five to six times per week to about two portions (pieces) of fruit per day. On the other hand, the control group, receiving only the TAU, experienced a small reduction in the consumption of fruit. Even though none of the groups met the nutritional recommendations for fruits and vegetables at the end of the intervention, our data suggest that the APOLO-Teens group was closer to meeting these guidelines (which include consuming at least five portions or 400 g a day). Considering that about 78% of Portuguese adolescents do not meet this recommendation [39] these findings highlight the potential role of this online tool in promoting healthy eating.

Improving vegetable consumption may not only depend on adolescents [40]. Eating preferences and choices of household members, particularly of mothers as the usual food providers, may have a negative effect on the adolescent’s food and beverages consumption and, consequently, on their readiness and aptitude for changing eating habits [40]. Thus, increasing vegetables on the plate and soup consumption can be more challenging for adolescents with no parental support since they are frequently fully dependent on their parents to buy and prepare these healthy options. Therefore, achieving a positive change in fruit consumption may be easier than in vegetable consumption since they do not depend directly on the parents to prepare the food, but rather on fruit availability and self-motivation [41,42,43]. A decrease in pastries/cakes consumption was found for both TAU and APOLO-Teens groups. These positive results in the TAU group were expected since both groups were receiving some kind of nutritional intervention and the ingestion of high caloric foods was already low at the beginning of the intervention.

Similarly to previous studies [20], this web-based intervention was not significantly effective in increasing physical activity in adolescents with overweight and obesity. Physical activity and exercise interventions have shown small and heterogeneous effects on this population [20]. A possible explanation for these poor outcomes may include the current physical activity recommendations for youth. Recommendations suggest that children/adolescents must engage in more than 60 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day to maintain a healthy lifestyle [44], but there are no specific physical activity recommendations for weight loss in this age range. For adults, the suggested dose of physical activity to lose weight is considerably higher (~5 h/week) when compared to the recommended physical activity for health [44]. In fact, in our sample, both groups met physical activity guidelines of 60 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day at the beginning of the intervention, which may hinder further changes.

The BMI z-score decreased in both groups and there were no significant differences between the groups. Still, these results should be carefully interpreted due to the sample size and mixed literature regarding the potential effect of web-based interventions on BMI z-score [15,16,20,45]. For instance, low adherence to intervention strategies can help to explain the low effectiveness that some studies found for interventions with adolescents with overweight and obesity [46,47] since high adherence to web-based interventions has been associated with superior outcomes [48,49].

The strengths of this study include the access to the clinical population undergoing treatment in public health care, the randomized clinical trial design, the use of anthropometric data collected from clinical charts, and the manualized intervention that offered the same intervention to all the APOLO-Teens group participants. Despite the strengths, some limitations should be considered in interpreting the present study results. Primarily, the sample size, the impossibility of estimating with precision the participant’s fruit and vegetable intake per day, and data missing in some of the outcome measures precluded the use of more complex statistical models. A per-protocol analysis was chosen to assess the effects of the APOLO-Teens intervention under conditions of adequate adherence, in line with our primary objective. While we also considered conducting an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis to account for all participants initially allocated to the intervention, this was not feasible due to the limited sample size and substantial missing outcome data. A comparison between completers and dropouts was not conducted, as it was not possible to determine with precision when or if participants disengaged from the intervention. All participants had continuous access to the Facebook-based content throughout the intervention period, and some continued to interact with the materials despite not completing the follow-up assessments.

Additionally, several variables were assessed using self-report measures (Rep(eat)-Q and YAP) and the results may be influenced by social desirability bias. Also, the use of the ChEAT total score can obfuscate potential data regarding particular disordered eating behaviors profiles.

Although overall feasibility was rated positively, some specific items received comparatively lower scores, namely, participants’ comfort in interacting with the group (3.3/5) and the perceived usefulness of the chat (3.2/5). Possible explanations include low familiarity with the platform, limited group cohesion, or a preference for more private or passive forms of interaction. To enhance engagement in future digital interventions, alternative platforms more aligned with adolescents’ communication preferences (e.g., Instagram, or WhatsApp) could be explored. Additionally, strategies such as moderated discussions, peer ambassadors, or structured interactive challenges may help foster a more dynamic and supportive online environment.

Given that the study was conducted within the Portuguese public health system—characterized by universal coverage, centralized governance, and predominantly public service provision—the generalizability of findings to other countries may be limited. Health systems with different organizational models (e.g., privatized) may encounter distinct implementation dynamics. Moreover, cultural factors such as societal attitudes toward public health interventions, trust in health care providers, and health-seeking behaviors can vary widely across countries and may influence the feasibility and effectiveness of similar interventions in other contexts. Nonetheless, the core principles underpinning the intervention, such as promoting patient engagement, targeting behavior change, and integrating multidisciplinary care are broadly applicable across diverse health care settings, particularly those committed to evidence-based practice and chronic disease prevention.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study reinforce the feasibility and potential of this intervention format to promote healthy eating behaviors, complementing existing adolescent weight loss practices in public health systems. Future research should include an untreated control group and a group with access solely to the web-based intervention in order to disentangle the effects of standard care and Facebook-based components. Exploring the effectiveness and adaptability of similar interventions delivered through other social media platforms will be relevant to determine whether comparable outcomes can be achieved beyond Facebook, since current trends indicate a decline in its popularity among adolescents, who increasingly favor platforms such as Instagram, TikTok, or messaging apps. To enhance engagement and reach, future adaptations should consider more widely used platforms among the target population, ensuring alignment with their digital habits and preferences.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17162586/s1; Figure S1: APOLO-Teens Facebook Intervention Interface; Figure S2: APOLO-Teens Web-Aplication Intervention Interface.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.R., E.C. and P.F.S.-M.; methodology, S.M.R., E.C., P.F.S.-M., H.F.M. and D.S.; formal analysis, S.M.R. and E.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.R., E.C. and P.F.S.-M.; writing—review and editing, S.M.R., E.C., P.F.S.-M., H.F.M. and D.S.; supervision, E.C. and P.F.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially conducted at the Psychology Research Center (PSI/01662), University of Minho, and supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education through national funds, and co-financed by FEDER through COMPETE2020 under the PT2020 Partnership Agreement (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-007653), by the following grant to Eva Conceição (POCI-01-0145-FEDER-028209), and doctoral scholarship to Sofia Ramalho (SFRH/BD/104182/2014). The work from Pedro Saint-Maurice was partially funded by an individual fellowship grant awarded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT; Portugal) (SFRH/BI/114330/2016) under the POPH/FSE program. This work was also partially supported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. by project reference <UID/04375/Centro de Investigação em Psicologia para o Desenvolvimento> and DOI identifier<10.54499/UIDB/04375/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04375/2020) and by project reference UIDB/00050: CPUP-Centre for Psychology at University of Porto.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was obtained from the University of Minho Ethics Review Board (SECVS 142/2015, approval date: 21 December 2015) and by the two hospital centers involved, namely São João University Hospital Center (HSJ/FMUP-1532015, approval date: 20 March 2015) and Oporto Hospital Center—Northern Maternal and Child Center [2015.192(164-DEFI/153-ES), approval date: 14 October 2015].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity |

| TAU | Treatment As Usual |

| Tb | Treatment Basline Assessment |

| Tf | End of intervention Assessment |

References

- Horesh, A.; Tsur, A.M.; Bardugo, A.; Twig, G. Adolescent and Childhood Obesity and Excess Morbidity and Mortality in Young Adulthood—A Systematic Review. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2021, 10, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, X.; Forrest, C.B.; Lê-Scherban, F.; Masino, A.J. Prediction of Early Childhood Obesity with Machine Learning and Electronic Health Record Data. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2021, 150, 104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.S.; Armstrong, S.C.; Michalsky, M.P.; Fox, C.K. Obesity in Adolescents A Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, K.; Sahoo, B.; Choudhury, A.K.; Sofi, N.Y.; Kumar, R.; Bhadoria, A.S. Childhood Obesity: Causes and Consequences. J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Xue, Y. Pediatric Obesity: Causes, Symptoms, Prevention and Treatment. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 11, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.A.; Patton, G.C.; Cini, K.I.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbas, N.; Abd Al Magied, A.H.A.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdoun, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity, 1990–2021, with Forecasts to 2050: A Forecasting Study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbeck, K.S.; Lister, N.B.; Gow, M.L.; Baur, L.A. Treatment of Adolescent Obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altman, M.; Wilfley, D.E. Evidence Update on the Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ells, L.J.; Rees, K.; Brown, T.; Mead, E.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Azevedo, L.; McGeechan, G.J.; Baur, L.; Loveman, E.; Clements, H.; et al. Interventions for Treating Children and Adolescents with Overweight and Obesity: An Overview of Cochrane Reviews. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 1823–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebeile, H.; Kelly, A.S.; O’Malley, G.; Baur, L.A. Obesity in Children and Adolescents: Epidemiology, Causes, Assessment, and Management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musetti, A.; Cattivelli, R.; Guerrini, A.; Mirto, A.M.; Riboni, F.V.; Varallo, G.; Castelnuovo, G.; Molinari, E. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy: Current Paths in the Management of Obesity. In Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Clinical Applications; InTech: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Skelton, J.A.; Beech, B.M. Attrition in Paediatric Weight Management: A Review of the Literature and New Directions. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e273–e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokholm, B.; Baker, J.L.; Sørensen, T.I.A. The Levelling off of the Obesity Epidemic since the Year 1999—A Review of Evidence and Perspectives. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mameli, C.; Krakauer, J.C.; Krakauer, N.Y.; Bosetti, A.; Ferrari, C.M.; Schneider, L.; Borsani, B.; Arrigoni, S.; Pendezza, E.; Zuccotti, G.V. Effects of a Multidisciplinary Weight Loss Intervention in Overweight and Obese Children and Adolescents: 11 Years of Experience. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e181095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flølo, T.N.; Tørris, C.; Riiser, K.; Almendingen, K.; Chew, H.S.J.; Fosså, A.; Albertini Früh, E.; Hennessy, E.; Leung, M.M.; Misvær, N.; et al. Digital Health Interventions to Treat Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents: An Umbrella Review. Obes. Rev. 2025, 26, e13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, V.; Virgolesi, M.; Vetrani, C.; Aprano, S.; Cantelli, F.; Di Martino, A.; Mercurio, L.; Iaccarino, G.; Isgrò, F.; Arpaia, P.; et al. Digital Interventions for Weight Control to Prevent Obesity in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1584595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Wood, G.; Skinner, B.; Thompson, J.L. The Effect of Social Media Interventions on Physical Activity and Dietary Behaviours in Young People and Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, G.; Weibel, N.; Patrick, K.; Fowler, J.H.; Norman, G.J.; Gupta, A.; Servetas, C.; Calfas, K.; Raste, K.; Pina, L.; et al. Click like to Change Your Behavior: A Mixed Methods Study of College Students’ Exposure to and Engagement with Facebook Content Designed for Weight Loss. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Chacon, B.; Suarez-Lledo, V.; Alvarez-Galvez, J. Use and Effectiveness of Social-Media-Delivered Weight Loss Interventions among Teenagers and Young Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotsalainen, H.; Kyngas, H.; Tammelin, T.; Heikkinen, H.; Kaariainen, M. Effectiveness of Facebook-Delivered Lifestyle Counselling and Physical Activity Self-Monitoring on Physical Activity and Body Mass Index in Overweight and Obese Adolescents: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 159205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez, L.; Langlois, J.; Legrand, K.; Quinet, M.-H.; Lecomte, E.; Omorou, A.Y.; Briançon, S. Reach and Acceptability of a Mobile Reminder Strategy and Facebook Group Intervention for Weight Management in Less Advantaged Adolescents: Insights From the PRALIMAP-INÈS Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aichner, T.; Grünfelder, M.; Maurer, O.; Jegeni, D. Twenty-Five Years of Social Media: A Review of Social Media Applications and Definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Teens, Social Media and Technology 2024; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Prout Parks, E.; Moore, R.H.; Li, Z.; Bishop-Gilyard, C.T.; Garrett, A.R.; Hill, D.L.; Bruton, Y.P.; Sarwer, D.B. Assessing the Feasibility of a Social Media to Promote Weight Management Engagement in Adolescents with Severe Obesity: Pilot Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, M.A.; Hayes, S.; Bennett, G.G.; Ives, A.K.; Foster, G.D. Using Facebook and Text Messaging to Deliver a Weight Loss Program to College Students. Obesity 2013, 21, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laranjo, L.; Arguel, A.; Neves, A.L.; Gallagher, A.M.; Kaplan, R.; Mortimer, N.; Mendes, G.A.; Lau, A.Y.S. The Influence of Social Networking Sites on Health Behavior Change: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2015, 22, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.A.; Lewis, L.K.; Ferrar, K.; Marshall, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Vandelanotte, C. Are Health Behavior Change Interventions That Use Online Social Networks Effective? A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, S.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Silva, D.; Mansilha, H.F.; Silva, C.; Gonçalves, S.; Machado, P.; Conceição, E. APOLO-Teens, a Web-Based Intervention for Treatment-Seeking Adolescents with Overweight or Obesity: Study Protocol and Baseline Characterization of a Portuguese Sample. Eat. Weight. Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 25, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Welk, G.J. Validity and Calibration of the Youth Activity Profile. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.; Pereira, A.; Saraiva, J.; Marques, M.; Soares, M.; Bos Carvalho, S.; Valente, J.; Azevedo, M.; Macedo, A. Portuguese Validation of the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test. Rev. Psiq. Clín. 2012, 39, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maloney, M.J.; McGuire, J.B.; Daniels, S.R. Reliability Testing of a Children’s Version of the Eating Attitude Test. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1988, 27, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.; Mitchell, J.E.; Machado, P.P.; Vaz, A.R.; Pinto-Bastos, A.; Ramalho, S.; Brandão, I.; Simões, J.; De Lourdes, M.; Freitas, A.C. Repetitive Eating Questionnaire [Rep (Eat )-Q ]: Enlightening the Concept of Grazing and Psychometric Properties in a Portuguese Sample. Appetite 2017, 117, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloster, A.T.; Rhoades, H.M.; Novy, D.; Klotsche, J.; Senior, A.; Kunik, M.; Wilson, N.; Stanley, M.A. Psychometric Properties of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 in Older Primary Care Patients. J. Affect. Disord 2008, 110, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Honrado, A.; Leal, I. Contribuição Para o Estudo Da Adaptação Portuguesa Das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 Itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2004, 5, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, L.; Guerra, M.P.; Lemos, M. Adaptação Da Escala Genérica Do Inventário Pediátrico de Qualidade de Vida—Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0—PedsQL, a Uma População Portuguesa. Rev. Port. Saude Publica 2009, 8, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Desmet, M.; Fillon, A.; Thivel, D.; Tanghe, A.; Braet, C. Attrition Rate and Predictors of a Monitoring MHealth Application in Adolescents with Obesity. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerowitz-Katz, G.; Ravi, S.; Arnolda, L.; Feng, X.; Maberly, G.; Astell-Burt, T. Rates of Attrition and Dropout in App-Based Interventions for Chronic Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Torres, D.; Oliveira, A.; Severo, M.; Alarcão, V.; Guiomar, S.; Mota, J.; Teixeira, P.; Rodrigues, S.; Lobato, L.; et al. Inquérito Alimentar Nacional e de Atividade Física, IAN-AF 2015-2016: Relatório de Resultados. 2017. Available online: www.ian-af.up.pt (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Chai, W.; Nepper, M.J. Associations of the Home Food Environment with Eating Behaviors and Weight Status among Children and Adolescents. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 5, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loth, K.A.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.R. Food-Related Parenting Practices and Child and Adolescent Weight and Weight-Related Behaviors. Clin. Pract. 2014, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepper, M.J.; Chai, W. Parental Views of Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Overweight Preschoolers and School-Aged Children. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2017, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkvord, F.; Naderer, B.; Coates, A.; Boyland, E. Promoting Fruit and Vegetable Consumption for Childhood Obesity Prevention. Nutrients 2021, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, A.A.; Chow, W.-C.; So, H.-K.; Yip, B.H.-K.; Li, A.M.; Kumta, S.M.; Woo, J.; Chan, S.-M.; Lau, E.Y.-Y.; Nelson, E.A.S. Lifestyle Intervention Using an Internet-Based Curriculum with Cell Phone Reminders for Obese Chinese Teens: A Randomized Controlled Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajie, W.N.; Chapman-Novakofski, K.M. Impact of Computer-Mediated, Obesity-Related Nutrition Education Interventions for Adolescents: A Systematic Review. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khudairy, L.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Mead, E.; Johnson, R.E.; Fraser, H.; Olajide, J.; Murphy, M.; Velho, R.M.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Diet, Physical Activity and Behavioural Interventions for the Treatment of Overweight or Obese Adolescents Aged 12 to 17 Years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD012651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelnuovo, G.; Manzoni, G.; Villa, V.; Cesa, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Molinari, E. The STRATOB Study: Design of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Brief Strategic Therapy with Telecare in Patients with Obesity and Binge-Eating Disorder Referred to Residential Nutritional Rehabilitation. Trials 2011, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, T.; Barker, M.; Jacob, C.M.; Morrison, L.; Lawrence, W.; Strömmer, S.; Vogel, C.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Farrell, D.; Inskip, H.; et al. A Systematic Review of Digital Interventions for Improving the Diet and Physical Activity Behaviors of Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).