Validating the Arabic Adolescent Nutrition Literacy Scale (ANLS): A Reliable Tool for Measuring Nutrition Literacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Human Ethics and Consent to Participate Declarations

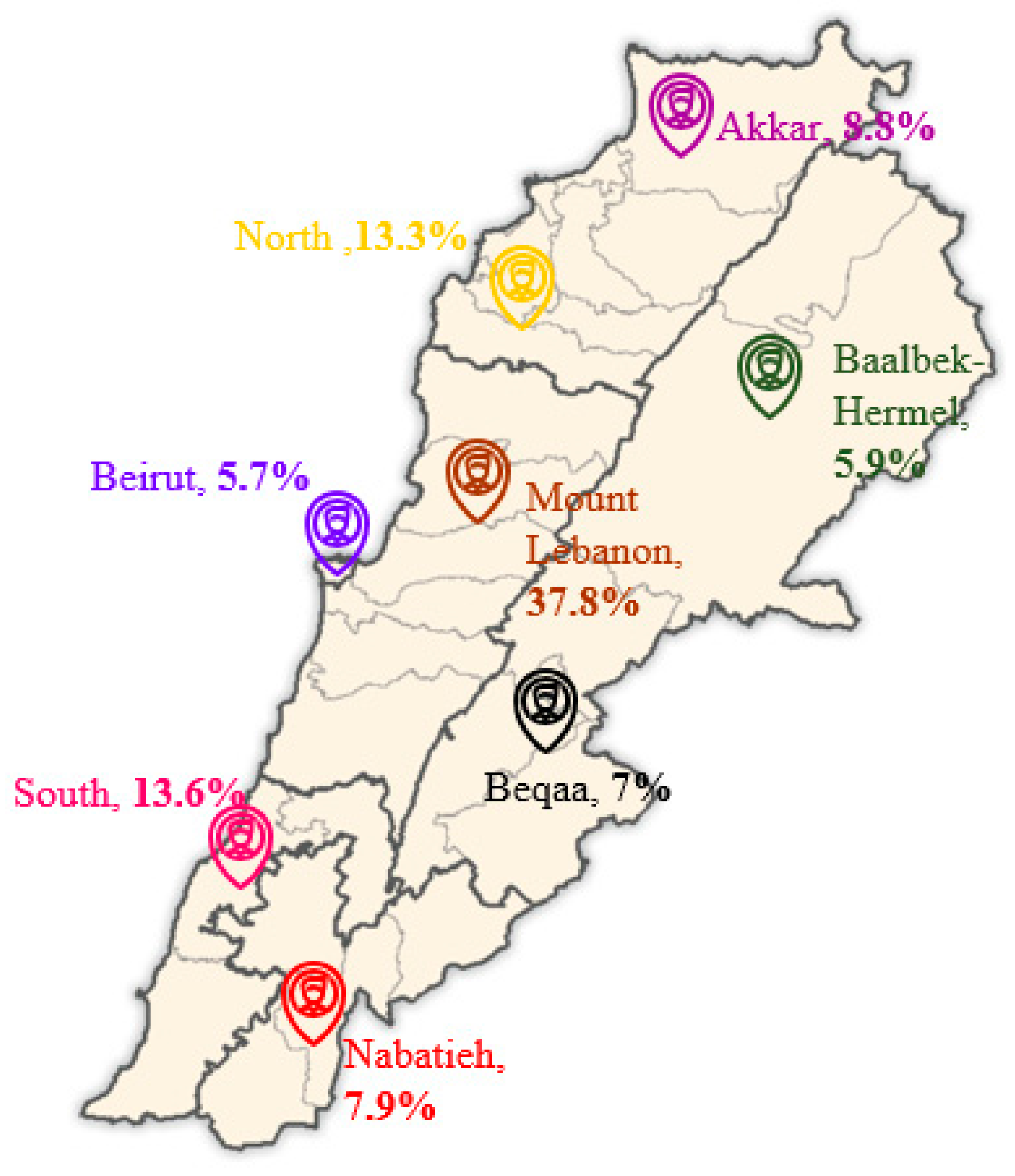

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection and Measures

2.4. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

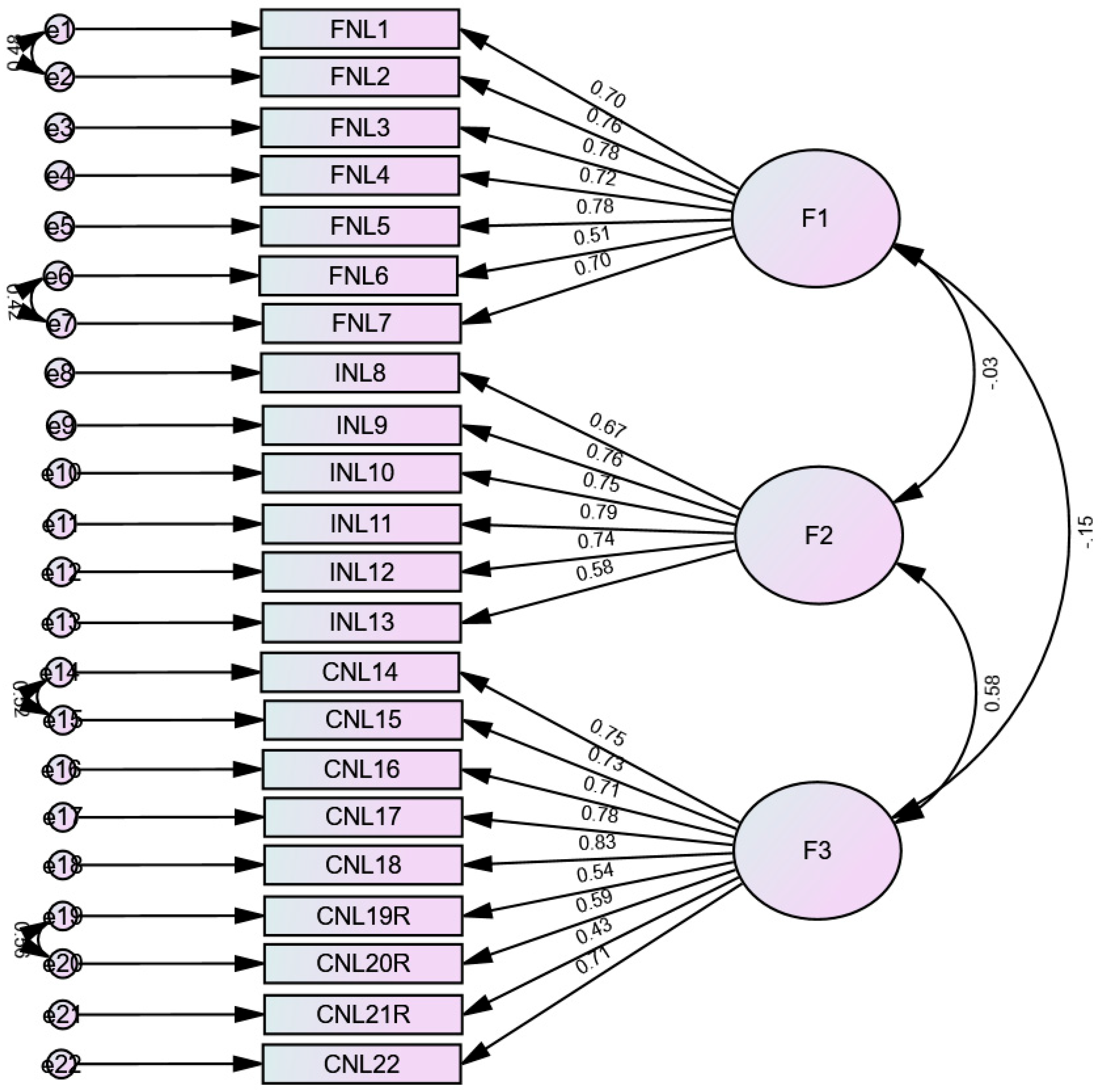

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Gender Invariance

3.3. Concurrent Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Factor Structure

4.2. Internal Reliability

4.3. Sex Invariance

4.4. Concurrent Validity

4.5. Clinical Implications

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koca, B.; Arkan, G. The relationship between adolescents’ nutrition literacy and food habits, and affecting factors. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santi, M.; Callari, F.; Brandi, G.; Toscano, R.V.; Scarlata, L.; Amagliani, G.; Schiavano, G.F. Mediterranean diet adherence and weight status among Sicilian Middle school adolescents. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 71, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alim, N.E.; Çalışkan, G.; Beşler, Z.N. Assessment of adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and behaviors of fruit and vegetable consumption in adolescents. Sağlık Bilim. Değer 2022, 12, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, M.H.; Nicolas, S.; O’Leary, O.F.; Nolan, Y.M. Outrunning a bad diet: Interactions between exercise and a Western-style diet for adolescent mental health, metabolism and microbes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 149, 105147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetou, V.; Kanellopoulou, A.; Kanavou, E.; Fotiou, A.; Stavrou, M.; Richardson, C.; Orfanos, P.; Kokkevi, A. Diet-related behaviors and diet quality among school-aged adolescents living in Greece. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Ding, L.; Zhang, R.; Ding, M.; Wang, B.; Yi, X. Physical activity, screen-based sedentary behavior and physical fitness in Chinese adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 722079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M.; del Carmen Morales-Ruán, M.; Hernández-Ávila, M.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.Á. Sobrepeso y obesidad en niños y adolescentes en México, actualización de la Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición de Medio Camino 2016. Salud Pública México 2018, 60, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, S.; Itani, L. Nutrition literacy among adolescents and its association with eating habits and BMI in Tripoli, Lebanon. Diseases 2021, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, M.K.; Sullivan, D.K.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Gajewski, B.J.; Gibbs, H.D. Nutrition literacy predicts adherence to healthy/unhealthy diet patterns in adults with a nutrition-related chronic condition. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2157–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a subtle difference? Findings from a systematic review on definitions of nutrition literacy and food literacy. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silk, K.J.; Sherry, J.; Winn, B.; Keesecker, N.; Horodynski, M.A.; Sayir, A. Increasing nutrition literacy: Testing the effectiveness of print, web site, and game modalities. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2008, 40, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, T.; Jung, H. The relationships between food literacy, health promotion literacy and healthy eating habits among young adults in South Korea. Foods 2022, 11, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, B.R.; Makarova, A.; Sidig, D.; Niazi, S.; Abddelgader, R.; Mirza, S.; Joud, H.; Urfi, M.; Ahmed, A.; Jureyda, O. Nutritional literacy among uninsured patients with diabetes mellitus: A free clinic study. Cureus 2021, 13, e16355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Girelli, L.; Mancone, S.; Valente, G.; Bellizzi, F.; Misiti, F.; Cavicchiolo, E. Psychometric properties and measurement invariance across gender of the Italian version of the tempest self-regulation questionnaire for eating adapted for young adults. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natour, N.; Al-Tell, M.; Ikhdour, O. Nutrition literacy is associated with income and place of residence but not with diet behavior and food security in the Palestinian society. BMC Nutr. 2021, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Doustmohammadian, A.; Omidvar, N.; Keshavarz-Mohammadi, N.; Eini-Zinab, H.; Amini, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Amirhamidi, Z.; Haidari, H. Low food and nutrition literacy (FNLIT): A barrier to dietary diversity and nutrient adequacy in school age children. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalkan, I. The impact of nutrition literacy on the food habits among young adults in Turkey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santaló, M.I.; Gibbons, S.; Naylor, P.-J. Using food models to enhance sugar literacy among older adolescents: Evaluation of a brief experiential nutrition education intervention. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustmohammadinan, A.; Omidvar, N.; Keshavarz Mohammadi, N.; Eini-Zinab, H.; Amini, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Esfandyari, S.; Amirhamidi, Z. Food and nutrition literacy (FNLIT) is associated to healthy eating behaviors in children. Nutr. Food Sci. Res. 2021, 8, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R.; Adinolfi, P.; Annarumma, C.; Catinello, G.; Tonelli, M.; Troiano, E.; Vezzosi, S.; Manna, R. Unravelling the food literacy puzzle: Evidence from Italy. Food Policy 2019, 83, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.D.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Gajewski, B.; Zhang, C.; Sullivan, D.K. The nutrition literacy assessment instrument is a valid and reliable measure of nutrition literacy in adults with chronic disease. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 247–257.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, H.D.; Kennett, A.R.; Kerling, E.H.; Yu, Q.; Gajewski, B.; Ptomey, L.T.; Sullivan, D.K. Assessing the nutrition literacy of parents and its relationship with child diet quality. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 505–509.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, H.D.; Ellerbeck, E.F.; Befort, C.; Gajewski, B.; Kennett, A.R.; Yu, Q.; Christifano, D.; Sullivan, D.K. Measuring nutrition literacy in breast cancer patients: Development of a novel instrument. J. Cancer Educ. 2016, 31, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustmohammadian, A.; Omidvar, N.; Keshavarz-Mohammadi, N.; Abdollahi, M.; Amini, M.; Eini-Zinab, H. Developing and validating a scale to measure Food and Nutrition Literacy (FNLIT) in elementary school children in Iran. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deesamer, S.; Piaseu, N.; Maneesriwongul, W.; Orathai, P.; Schepp, K.G. Development and Psychometric Testing of the Thai-Nutrition Literacy Assessment Tool for Adolescents. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 24, 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guttersrud, Ø.; Petterson, K.S. Young adolescents’ engagement in dietary behaviour–the impact of gender, socio-economic status, self-efficacy and scientific literacy. Methodological aspects of constructing measures in nutrition literacy research using the Rasch model. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2565–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naigaga, D.A.; Pettersen, K.S.; Henjum, S.; Guttersrud, Ø. Assessing adolescents’ perceived proficiency in critically evaluating nutrition information. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, O.; Quinn, E.L.-H.; Ramirez, M.; Sawyer, V.; Eimicke, J.P.; Teresi, J.A. Development of a menu board literacy and self-efficacy scale for children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 867–871.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.S.; Treu, J.A.; Njike, V.; Walker, J.; Smith, E.; Katz, C.S.; Katz, D.L. The validation of a food label literacy questionnaire for elementary school children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2012, 44, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, K.; Todoriki, H.; Sasaki, S. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake among primary school children in Japan: Combined effect of children’s and their guardians’ knowledge. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.-L.; Lai, I.-J. Construction of nutrition literacy indicators for college students in Taiwan: A Delphi consensus study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 734–742.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Su, X.; Li, N.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, G.; Zhu, W. Delphi method on food and nutrition literacy core components for school-age children. Chin. J. Health. Educ. 2020, 36, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wen, J.; Ma, H.; Yin, X.; Wang, J. Establishment of nutrition literacy core items for Chinese preschool children. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 54, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Medicine, I.O.; Neuroscience, B.O.; Health, B.; Literacy, C.O.H. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bari, N.N. Nutrition Literacy Status of Adolescent Students in Kampala District, Uganda. Master’s Thesis, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Lillestrøm, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmen, A.S.; Kalkan, I.; Filiz, E. Adaptation of adolescent nutrition literacy scale into Turkish: A validity and reliability study. Int. Peer-Rev. J. Nutr. Res. 2017, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joulaei, H.; Keshani, P.; Kaveh, M.H. Nutrition literacy as a determinant for diet quality amongst young adolescents: A cross sectional study. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 455–464. [Google Scholar]

- Depboylu, G.Y.; Kaner, G.; Süer, M.; Kanyılmaz, M.; Alpan, D. Nutrition literacy status and its association with adherence to the Mediterranean diet, anthropometric parameters and lifestyle behaviours among early adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Mansour, R.; Mohsen, H.; Bookari, K.; Hammouh, F.; Allehdan, S.; Alkazemi, D.; Al Sabbah, H.; Benkirane, H.; Kamel, I.; et al. Status and correlates of food and nutrition literacy among parents-adolescents’ dyads: Findings from 10 Arab countries. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1151498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger and Malnutrition in the Arab Region Stand in the Way of Achieving Zero Hunger by 2030. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/mena/press-releases/hunger-and-malnutrition-arab-region-stand-way-achieving-zero-hunger-2030-un-report (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Food and Agricultural Organization; International Fund for Agricultural Development; United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund; World Food Program; World Health Organization, Economic SCfWA. Near East and North Africa Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2020: Enhancing Resilience of food Systems in the Arab States. 2021. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/275622ec-df5b-4198-b72c-757f681e236c/content (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Agence France-Presse. A Third of People in 420m-Strong Arab World Do Not Have Enough to Eat Arab News. 2021. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1988326/middle-east (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- El Zouki, C.-J.; Chahine, A.; Mhanna, M.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Rate and correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following the Beirut blast and the economic crisis among Lebanese University students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naja, F.; Hwalla, N.; Itani, L.; Karam, S.; Sibai, A.M.; Nasreddine, L. A Western dietary pattern is associated with overweight and obesity in a national sample of Lebanese adolescents (13–19 years): A cross-sectional study. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, H.; Zind, M.; Garnier, S.; Fazah, A.; Jacob, C.; Moussa, E.; Gratas-Delamarche, A.; Groussard, C. Overweight and obesity related factors among Lebanese adolescents: An explanation for gender and socioeconomic differences. Epidemiology 2017, 7, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.S. Physical Activity Among a Representative Sample of Lebanese Adolescents Aged 12–18 Years: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Ph.D. Thesis, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to Support Country Implementation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Laska, M.N.; Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Does involvement in food preparation track from adolescence to young adulthood and is it associated with better dietary quality? Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoghby, H.B.; Sfeir, E.; Akel, M.; Malaeb, D.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Knowledge, attitude and practice of Lebanese parents towards childhood overweight/obesity: The role of parent-physician communication. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. Intakes of energy and macronutrient from Chinses 15 provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities) adults aged 18 to 35 in 1989-2018. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu J. Hyg. Res. 2022, 51, 361–380. [Google Scholar]

- Desbouys, L.; De Ridder, K.; Rouche, M.; Castetbon, K. Food consumption in adolescents and young adults: Age-specific socio-economic and cultural disparities (Belgian Food Consumption Survey 2014). Nutrients 2019, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, F.; Azadbakht, L. A systematic review on diet quality among Iranian youth: Focusing on reports from Tehran and Isfahan. Arch. Iran. Med. 2014, 17, 574–584. [Google Scholar]

- Vella-Zarb, R.A.; Elgar, F.J. The ‘freshman 5’: A meta-analysis of weight gain in the freshman year of college. J. Am. Coll. Health 2009, 58, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.T.; Zoellner, J.M. Nutrition and health literacy: A systematic review to inform nutrition research and practice. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikimedia Commons. Lebanon Districts. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lebanon_districts.png (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Jamaluddine, Z.; Sahyoun, N.R.; Choufani, J.; Sassine, A.J.; Ghattas, H. Child-Reported Food Insecurity Is Negatively Associated with Household Food Security, Socioeconomic Status, Diet Diversity, and School Performance among Children Attending UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees Schools in Lebanon. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 2228–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundfrom, D.J.; Shaw, D.G.; Ke, T.L. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int. J. Test. 2005, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu Lt Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.; Dash, S. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation; Pearson-Dorling Kindersley: Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF: Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2007, 14, 464–504. [CrossRef]

- Vadenberg, R.; Lance, C. A review and synthesis of the measurement in variance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organ Res. Methods 2000, 3, 4–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Todd, J.; Azzi, V.; Malaeb, D.; El Dine, A.S.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Psychometric properties of an Arabic translation of the Functionality Appreciation Scale (FAS) in Lebanese adults. Body Image 2022, 42, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, T.J.; Baguley, T.; Brunsden, V. From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br. J. Psychol. 2014, 105, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazel, G.; Bozdogan, S. Nutrition literacy, dietary habits and food label use among Turkish adolescents. Prog. Nutr. 2021, 23, e2021007. [Google Scholar]

- Ashoori, M.; Omidvar, N.; Eini-Zinab, H.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Doustmohamadian, A.; Abdar-Esfahani, B.; Mazandaranian, M. Food and nutrition literacy status and its correlates in Iranian senior high-school students. BMC Nutr. 2021, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A. Body image and weight control in young adults: International comparisons in university students from 22 countries. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-P. Gender differences in nutrition knowledge, attitude, and practice among elderly people. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Soc. Sci. (IJMESS) 2017, 6, 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen, K.; Torheim, L.E.; Fjelberg, V.; Sorprud, A.; Narverud, I.; Retterstøl, K.; Bogsrud, M.P.; Holven, K.B.; Myhrstad, M.C.; Telle-Hansen, V.H. Gender differences in nutrition literacy levels among university students and employees: A descriptive study. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullan, B.A.; Wong, C.; Kothe, E.J. Predicting adolescents’ safe food handling using an extended theory of planned behavior. Food Control 2013, 31, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliffe, J.L.; Rossnagel, E.; Kelly, M.T.; Bottorff, J.L.; Seaton, C.; Darroch, F. Men’s health literacy: A review and recommendations. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landry, M.J.; van den Berg, A.E.; Asigbee, F.M.; Vandyousefi, S.; Ghaddar, R.; Davis, J.N. Child-report of food insecurity is associated with diet quality in children. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J.; Frongillo, E.A.; Rivera, J.A. Food insecurity reported by children, but not by mothers, is associated with lower quality of diet and shifts in foods consumed. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorramrouz, F.; Doustmohammadian, A.; Eslami, O.; Khadem-Rezaiyan, M.; Pourmohammadi, P.; Amini, M.; Khosravi, M. Relationship between household food insecurity and food and nutrition literacy among children of 9–12 years of age: A cross-sectional study in a city of Iran. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.H.; Szeto, K.; Lensing, S.; Bogle, M.; Weber, J. Children in food-insufficient, low-income families: Prevalence, health, and nutrition status. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2001, 155, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liese, A.D.; Bell, B.A.; Martini, L.; Hibbert, J.; Draper, C.; Burke, M.P.; Jones, S.J. Perceived and geographic food access and food security status among households with children. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2781–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- School Health and Nutrition. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/health-education/nutrition (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hunter, D.; Giyose, B.; PoloGalante, A.; Tartanac, F.; Bundy, D.; Mitchell, A.; Moleah, T.; Friedrich, J.; Alderman, A.; Drake, L.; et al. Schools as a System to Improve Nutrition: A New Statement for School-Based Food and Nutrition Interventions; United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 246 (55.7%) |

| Female | 196 (44.3%) |

| Education level | |

| Primary | 112 (25.3%) |

| Complementary | 119 (26.9%) |

| Secondary | 122 (27.6%) |

| University | 89 (20.1%) |

| School type | |

| I am currently not attending school | 51 (11.6%) |

| Public school | 168 (38.1%) |

| Private school | 222 (50.3%) |

| Mean ± SD | |

| Age (years) | 14.66 ± 2.94 |

| Model | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Model Comparison | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 0.918 | 0.067 | 0.060 | ||||

| Females | 0.893 | 0.084 | 0.084 | ||||

| Configural | 0.906 | 0.053 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 0.002 | <0.001 | |

| Metric | 0.908 | 0.051 | 0.060 | Configural vs. metric | 0.002 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

| Scalar | 0.906 | 0.051 | 0.060 | Metric vs. scalar | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Obeid, S.; Hallit, S.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Sacre, Y.; Hokayem, M.; Saeidi, A.; Sabbah, L.; Tzenios, N.; Hoteit, M. Validating the Arabic Adolescent Nutrition Literacy Scale (ANLS): A Reliable Tool for Measuring Nutrition Literacy. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152457

Obeid S, Hallit S, Fekih-Romdhane F, Sacre Y, Hokayem M, Saeidi A, Sabbah L, Tzenios N, Hoteit M. Validating the Arabic Adolescent Nutrition Literacy Scale (ANLS): A Reliable Tool for Measuring Nutrition Literacy. Nutrients. 2025; 17(15):2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152457

Chicago/Turabian StyleObeid, Sahar, Souheil Hallit, Feten Fekih-Romdhane, Yonna Sacre, Marie Hokayem, Ayoub Saeidi, Lamya Sabbah, Nikolaos Tzenios, and Maha Hoteit. 2025. "Validating the Arabic Adolescent Nutrition Literacy Scale (ANLS): A Reliable Tool for Measuring Nutrition Literacy" Nutrients 17, no. 15: 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152457

APA StyleObeid, S., Hallit, S., Fekih-Romdhane, F., Sacre, Y., Hokayem, M., Saeidi, A., Sabbah, L., Tzenios, N., & Hoteit, M. (2025). Validating the Arabic Adolescent Nutrition Literacy Scale (ANLS): A Reliable Tool for Measuring Nutrition Literacy. Nutrients, 17(15), 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152457