Use of Botanical Supplements Among Romanian Individuals with Diabetes: Results from an Online Study on Prevalence, Practices, and Glycemic Control

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Information

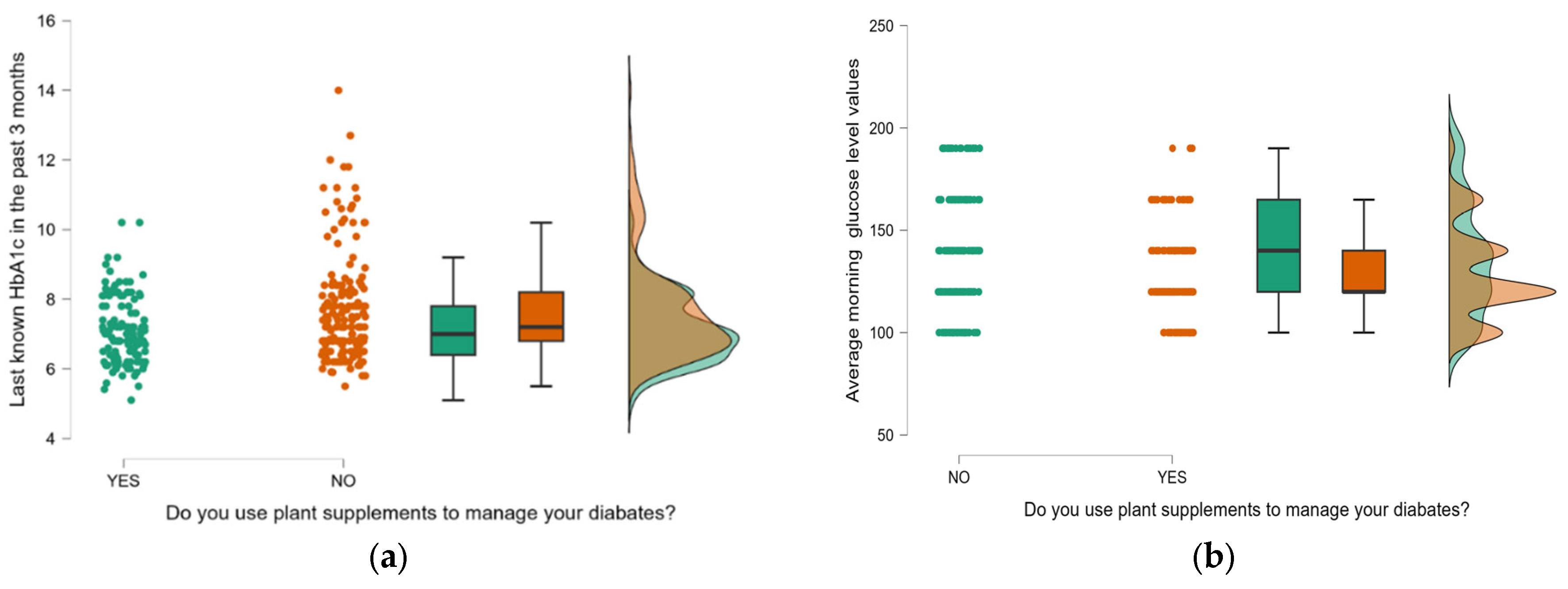

2.2. Plant Supplement Use

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Participants

4.2. Questionnaire Development

4.3. Validation of the Questionnaire

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| DPP4 | dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| EFA | exploratory factor analysis |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| HbA1c | glycated hemoglobin |

| SGLT2 | sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 |

References

- Petersmann, A.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Müller, U.A.; Landgraf, R.; Nauck, M.; Freckmann, G.; Heinemann, L.; Schleicher, E. Definition, classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2019, 127, S1–S7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngugi, M.P.; Nzaro, G.M.; Njagi, J.M. Diabetes mellitus-a devastating metabolic disorder. Asian J. Biomed. Pharma Sci. 2015, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Ren, Y.; Shan, P.F. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14790–14791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCreight, L.J.; Bailey, C.J.; Pearson, E.R. Metformin and the gastrointestinal tract. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, B.; Patil, N.G.; Fok, M.; Chan, P.; Lam, C.W.K. The role of sulfonylureas in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2022, 23, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, R.; Bridgeman, M.B. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-4) Inhibitors in the Management of Diabetes. Pharm. Ther. 2010, 35, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilbon, S.S.; Kolonin, M.G. GLP1 Receptor Agonists-Effects beyond Obesity and Diabetes. Cells 2023, 28, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, D.S.; Grove, O.; Cefalu, W.T. An update on sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2017, 24, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethi, P.J. Herbal medicine for diabetes mellitus: A Review. Int. J. Phytopharm. 2013, 3, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bungau, S.G.; Popa, V.-C. Between religion and science: Some aspects: Concerning illness and healing in antiquity. Transylv. Rev. 2015, 26, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gureje, O.; Nortje, G.; Makanjuola, V.; Oladeji, B.D.; Seedat, S.; Jenkins, R. The role of global traditional and complementary systems of medicine in the treatment of mental health disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Noh, S.; Lim, S.; Kim, B. Plant Extracts for Type 2 Diabetes: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Drug Discovery. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.Q.; Kam, A.; Wong, K.H.; Zhou, X.; Omar, E.A.; Alqahtani, A.; Li, K.M.; Razmovski-Naumovski, V.; Chan, K. Herbal Medicines for the Management of Diabetes. In Diabetes: An Old Disease, a New Insight, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Ahmad, S.I., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeem, M.I.; Davies, T.C. Anti-Diabetic Functional Foods as Sources of Insulin Secreting, Insulin Sensitizing and Insulin Mimetic Agents. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 20, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiyorini, E.; Qomaruddin, M.B.; Wibisono, S.; Juwariah, T.; Setyowati, A.; Wulandari, N.A.; Sari, Y.K.; Sari, L.T. Complementary and alternative medicine for glycemic control of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. J. Public Health Res. 2022, 8, 22799036221106582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungurianu, A.; Şeremet, O.; Gagniuc, E.; Olaru, O.T.; Guţu, C.; Grǎdinaru, D.; Ionescu-Tȋrgovişte, C.; Marginǎ, D.; Dǎnciulescu-Miulescu, R. Preclinical and clinical results regarding the effects of a plant-based antidiabetic formulation versus well established antidiabetic molecules. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 150, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olah, N.K.; Petrescu, S.; Marian, E.; Jurca, T.; Marc, F.; Dobjanschi, L.; Honiges, A.; Kiss, R.; Bechir, E.S.; Bechir, F.; et al. The Study of Antioxidant Capacity in Extracts from Vegetal Sources with Hypoglycaemic Action. Rev. Chim. 2019, 70, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Alvarez, A.; Egan, B.; de Klein, S.; Dima, L.; Maggi, F.M.; Isoniemi, M.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Raats, M.M.; Meissner, E.M.; Badea, M.; et al. Usage of plant food supplements across six European countries: Findings from the PlantLIBRA consumer survey. PLoS ONE 2014, 18, e92265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, E.; Erkin, O.; Senman, S.; Yildirim, Y. The use of herbal supplements by individuals with diabetes mellitus. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018, 68, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almogbel, E.S.; AlHotan, F.M.; AlMohaimeed, Y.A.; Aldhuwayhi, M.I.; AlQahtani, S.W.; Alghofaili, S.M.; Bedaiwi, B.F.; AlHajjaj, A.H. Habits, Traditions, and Beliefs Associated with the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Among Diabetic Patients in Al-Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 31, e33157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, H.; Hasan, H.; Hamadeh, R.; Hashim, M.; Abdul Wahid, Z.; Hassanzadeh Gerashi, M.; Al Hilali, M.; Naja, F. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with type 2 diabetes living in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekuria, A.B.; Belachew, S.A.; Tegegn, H.G.; Ali, D.S.; Netere, A.K.; Lemlemu, E.; Erku, D.A. Prevalence and correlates of herbal medicine use among type 2 diabetic patients in Teaching Hospital in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laczkó Zöld, E.; Toth, L.M.; Farczadi, L.; Ştefănescu, R. Polyphenolic profile and antioxidant properties of Momordica charantia L. ‘Enaja’ cultivar grown in Romania. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 38, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josep, B.; Jini, D. Antidiabetic effects of Momordica charantia (bitter melon) and its medicinal potency. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2013, 3, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, E.L.; Kasali, F.M.; Deyno, S.; Mtewa, A.; Nagendrappa, P.B.; Tolo, C.U.; Ogwang, P.E.; Sesaazi, D. Momordica charantia L. lowers elevated glycaemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 231, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budrat, P.; Shotipruk, A. Extraction of phenolic compounds from fruits of bitter melon (Momordica charantia) with subcritical water extraction and antioxidant activities of these extracts. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2008, 35, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Song, Y.; Miao, M. Effects of Momordica charantia L. supplementation on glycemic control and lipid profile in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifle, Z.D.; Bayleyegn, B.; Yimer Tadesse, T.; Woldeyohanins, A.E. Prevalence and associated factors of herbal medicine use among adult diabetes mellitus patients at government hospital, Ethiopia: An institutional-based cross-sectional study. Metabol. Open 2021, 26, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani, S.; Falahatzadeh, M.; Oveil, E.; Jamali, M.; Pam, P.; Parang, M.; Shakarami, M. The effect of Nigella sativa supplementation on glycemic status in adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2024, 174, 106885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehzad, M.J.; Ghalandari, H.; Nouri, M.; Askarpour, M. Effects of curcumin/turmeric supplementation on glycemic indices in adults: A grade-assessed systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2023, 17, 102855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păduraru, D.N. The use of nutritional supplement in Romanian patients—Attitudes and beliefs. Farmacia 2019, 67, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foghis, M.; Tit, D.M.; Bungau, S.G.; Ghitea, T.C.; Pallag, C.R.; Foghis, A.M.; Behl, T.; Bustea, C.; Pallag, A. Highlighting the Use of the Hepatoprotective Nutritional Supplements among Patients with Chronic Diseases. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | YES (N = 145) | NO (N = 184) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.62 62 | ±11.62 [16.0] | 58.875 59.5 | ±13.04 [16.3] | 0.068 1 |

| Diabetes duration (years) | 8.33 5.0 | ±7.79 [10.0] | 9.745 8.0 | ±8.03 [11.0] | 0.068 1 |

| Living environment | |||||

| Urban | 95 | 65.52 | 108 | 58.70 | 0.206 2 |

| Rural | 50 | 34.48 | 76 | 41.30 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 46 | 31.72 | 82 | 44.57 | 0.018 2,* |

| Female | 99 | 68.28 | 102 | 55.43 | |

| Diabetes type | |||||

| Type 1 | 5 | 3.45 | 13 | 7.07 | 0.152 2 |

| Type 2 | 140 | 96.55 | 171 | 92.93 | |

| Schooling | |||||

| Medium | 82 | 56.55 | 122 | 66.30 | 0.291 2 |

| Higher education | 48 | 33.10 | 44 | 23.91 | |

| Elementary school | 14 | 9.66 | 17 | 9.24 | |

| No education | 1 | 0.69 | 1 | 0.54 | |

| Working situation | |||||

| Retired | 69 | 47.59 | 79 | 42,93 | 0.799 2 |

| Working | 71 | 48.97 | 96 | 52,17 | |

| Housewife | 3 | 2.07 | 6 | 3,26 | |

| Unemployed | 2 | 1.38 | 3 | 1.63 | |

| Treatment | |||||

| Biguanides | 65 | 44.83 | 84 | 45.65 | 0.881 2 |

| Sulphonyl urea | 21 | 14.48 | 18 | 9.78 | 0.190 2 |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 25 | 17.24 | 26 | 14.13 | 0.4392 |

| GLP-1agonists | 25 | 17.24 | 20 | 10.87 | 0.090 2 |

| DPP4 inhibitors | 10 | 6.90 | 9 | 4.89 | 0.439 2 |

| SGLT2 + metformin | 11 | 7.59 | 15 | 8.15 | 0.850 2 |

| Biguanides + sulphonyl urea | 2 | 1.38 | 3 | 1.63 | 0.853 2 |

| Biguanides + DPP4 | 1 | 0.69 | 3 | 1.63 | 0.439 2 |

| Basal insulin | 28 | 19.31 | 58 | 31.52 | 0.027 2,* |

| Basal insulin + GLP1 | 1 | 0.69 | 3 | 1.63 | 0.439 2 |

| Rapid insulin | 8 | 5.52 | 19 | 10.33 | 0.115 2 |

| Premixed insulin | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.54 | - |

| No medication | 8 | 5.52 | 2 | 1.09 | 0.020 * |

| Average Morning Glucose Levels (mg/dL) | YES (N = 145) | NO (N = 184) | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | |

| <110 | 30 | 20.69 | 37 | 20.11 | 67 |

| 110–130 | 60 | 41.38 | 47 | 25.54 | 107 |

| 130–150 | 33 | 22.76 | 51 | 27.72 | 84 |

| 150–180 | 19 | 13.10 | 30 | 16.30 | 49 |

| >180 | 3 | 2.07 | 19 | 10.33 | 22 |

| Total | 145 | 100.00 | 184 | 100.00 | 329 |

| Plant Supplement Use | YES (N = 145) | NO (N = 184) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | % | ||

| HbA1c ≥ 6.5% | 71.03 | 85.87 | p < 0.001 OR = 0.404 * 95%CI ∈ (0.233; 0.698) |

| HbA1c < 6.5% | 28.97 | 14.13 | |

| Morning glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL | 74.48 | 83.70 | p = 0.039 OR = 0.569 * 95%CI ∈ (0.33; 0.976) |

| Morning glucose < 100 mg/dL | 25.52 | 16.30 | |

| Plant Supplement Use | YES (N = 145) | NO (N = 184) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Polyneuropathy | |||||

| Yes | 45 | 31.03 | 78 | 42.39 | 0.035 * |

| No | 100 | 68.97 | 106 | 57.61 | |

| Chronic kidney Disease | |||||

| Yes | 14 | 9.66 | 13 | 7.07 | 0.395 |

| No | 131 | 90.34 | 171 | 92.93 | |

| Retinopathy | |||||

| Yes | 29 | 20.00 | 38 | 20.65 | 0.884 |

| No | 116 | 80.00 | 146 | 79.35 | |

| What Type of Plant Supplement do You Use? | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Name | Latin Name | ||

| Momordica | Momordica charantia L. | 51 | 35.17 |

| Spirulina | Arthrospira platensis (Gomont) | 2 | 1.38 |

| Evening primrose | Oenothera biennis L. | 1 | 0.69 |

| Plant combination | - | 23 | 15.86 |

| Berberine | Berberis aristata DC | 6 | 4.14 |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa L. | 9 | 6.21 |

| Blueberry | Vaccinium angustifolium Aiton | 22 | 15.17 |

| Sage | Salvia officinalis L. | 4 | 2.76 |

| Resveratrol | - | 1 | 0.69 |

| Mulberry | Morus sp. | 4 | 2.76 |

| Dandelion | Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg. | 6 | 4.14 |

| Blackseed | Nigella sativa L. | 11 | 7.59 |

| Blackcurrant | Ribes nigrum L. | 4 | 2.76 |

| Cinnamon | Cinnamomum verum J.Presl | 1 | 0.69 |

| Details of Plant Combination (N = 23) | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Momordica, olive extract, fenugreek, cinnamon | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, blueberry | 1 | 0.69 |

| Blueberry, guince | 1 | 0.69 |

| Gymnema, cinnamon | 2 | 1.37 |

| Gymnema, mulberry | 1 | 0.69 |

| Plant supplement with over 30 herbs | 1 | 0.69 |

| Spirulina, sage, mint, rosehip | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, blueberry | 1 | 0.69 |

| Dandelion, bean pods, corn silk | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, gymnema, blueberry, green tea | 1 | 0.69 |

| Curcumin, momordica | 1 | 0.69 |

| Mulberry, blueberry, rosehip | 1 | 0.69 |

| Gingko biloba, blueberry, black seed | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, berberine | 1 | 0.69 |

| Dandelion, berberine | 1 | 0,69 |

| Berberine, blueberry | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, green tea | 1 | 0.69 |

| Mulberry, gymnema | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, mulberry | 1 | 0.69 |

| Momordica, blueberry, guince, walnut | 1 | 0.69 |

| Curcumin, momordica, fenugreek, amla, chirata, gymnema, chinaberry tree, jaman, gurjo | 2 | 1.37 |

| What is the Pharmaceutical form of These Supplements? | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Tea | 17 | 11.72 |

| Capsules | 95 | 65.52 |

| Tablets | 26 | 17.93 |

| Tincture | 7 | 4.83 |

| Parameter | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Why have you started to use plant supplements to manage your disease? | ||

| To improve blood glucose levels | 129 | 88.97 |

| To prevent diabetes complications | 40 | 27.59 |

| To reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease | 18 | 12.41 |

| To manage diabetes complications | 13 | 8.97 |

| To improve general health | 16 | 11.03 |

| Other | 1 | 0.69 |

| Why do you continue to use plant supplements to manage your disease? | ||

| I trust their effect | 101 | 69.66 |

| I noticed that my blood sugars levels are better | 29 | 20.00 |

| I am not satisfied with classical medication | 20 | 13.79 |

| Friends or family use them, and I follow their example | 10 | 6.90 |

| Other | 3 | 2.07 |

| How long have you been using this supplement? | ||

| >1 year | 61 | 42.07 |

| 3–6 months | 30 | 20.69 |

| Less than 3 months | 30 | 20.69 |

| 6 months–1 year | 24 | 16.55 |

| This supplement was recommended to you by: | ||

| Doctor | 39 | 26.90 |

| Pharmacist | 29 | 20.00 |

| Mass media | 11 | 7.59 |

| I took it on my own initiative | 59 | 40.69 |

| Personal documentation | 1 | 0.69 |

| Friends | 6 | 4.14 |

| What dose do you use? | ||

| The dose recommended by the doctor/pharmacist | 65 | 44.83 |

| The dose on the leaflet | 53 | 36.55 |

| I don’t have a specific rule regarding the dose I take | 27 | 18.62 |

| What changes have you noticed since using this supplement? | ||

| Significant improvement in health | 78 | 53.79 |

| No improvement | 15 | 10.34 |

| Little improvement in health | 52 | 35.86 |

| Parameters | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| I have lower glycemic values in the morning | 102 | 70.34 |

| I have lower glycemic values after meals | 41 | 28.28 |

| I have lower HbA1c | 50 | 34.48 |

| I lost weight | 23 | 15.86 |

| Blood pressure improved | 21 | 14.48 |

| Cholesterol improved | 12 | 8.28 |

| No parameter improved | 15 | 10.34 |

| Parameters | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| I do not trust their effect | 80 | 43.48 |

| I’m afraid of the side effects | 23 | 12.50 |

| I can’t afford it financially | 24 | 13.04 |

| My doctor didn’t recommend it | 70 | 38.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vesa, C.M.; Tit, D.M.; Babes, E.E.; Bungau, G.; Radu, A.-F.; Moleriu, R.D. Use of Botanical Supplements Among Romanian Individuals with Diabetes: Results from an Online Study on Prevalence, Practices, and Glycemic Control. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152440

Vesa CM, Tit DM, Babes EE, Bungau G, Radu A-F, Moleriu RD. Use of Botanical Supplements Among Romanian Individuals with Diabetes: Results from an Online Study on Prevalence, Practices, and Glycemic Control. Nutrients. 2025; 17(15):2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152440

Chicago/Turabian StyleVesa, Cosmin Mihai, Delia Mirea Tit, Emilia Elena Babes, Gabriela Bungau, Andrei-Flavius Radu, and Radu Dumitru Moleriu. 2025. "Use of Botanical Supplements Among Romanian Individuals with Diabetes: Results from an Online Study on Prevalence, Practices, and Glycemic Control" Nutrients 17, no. 15: 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152440

APA StyleVesa, C. M., Tit, D. M., Babes, E. E., Bungau, G., Radu, A.-F., & Moleriu, R. D. (2025). Use of Botanical Supplements Among Romanian Individuals with Diabetes: Results from an Online Study on Prevalence, Practices, and Glycemic Control. Nutrients, 17(15), 2440. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152440