Examining Food Sources and Their Interconnections over Time in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- where is the existing evidence drawn from?

- what are the links between food sources and health and nutrition, and with broader aspects such as social, cultural, economic, and environmental dimensions?

- what are their changes over time and across generations?

- what are the interconnections between these food sources?

- what is the extent of the existing evidence, and how has it been conceptualised?

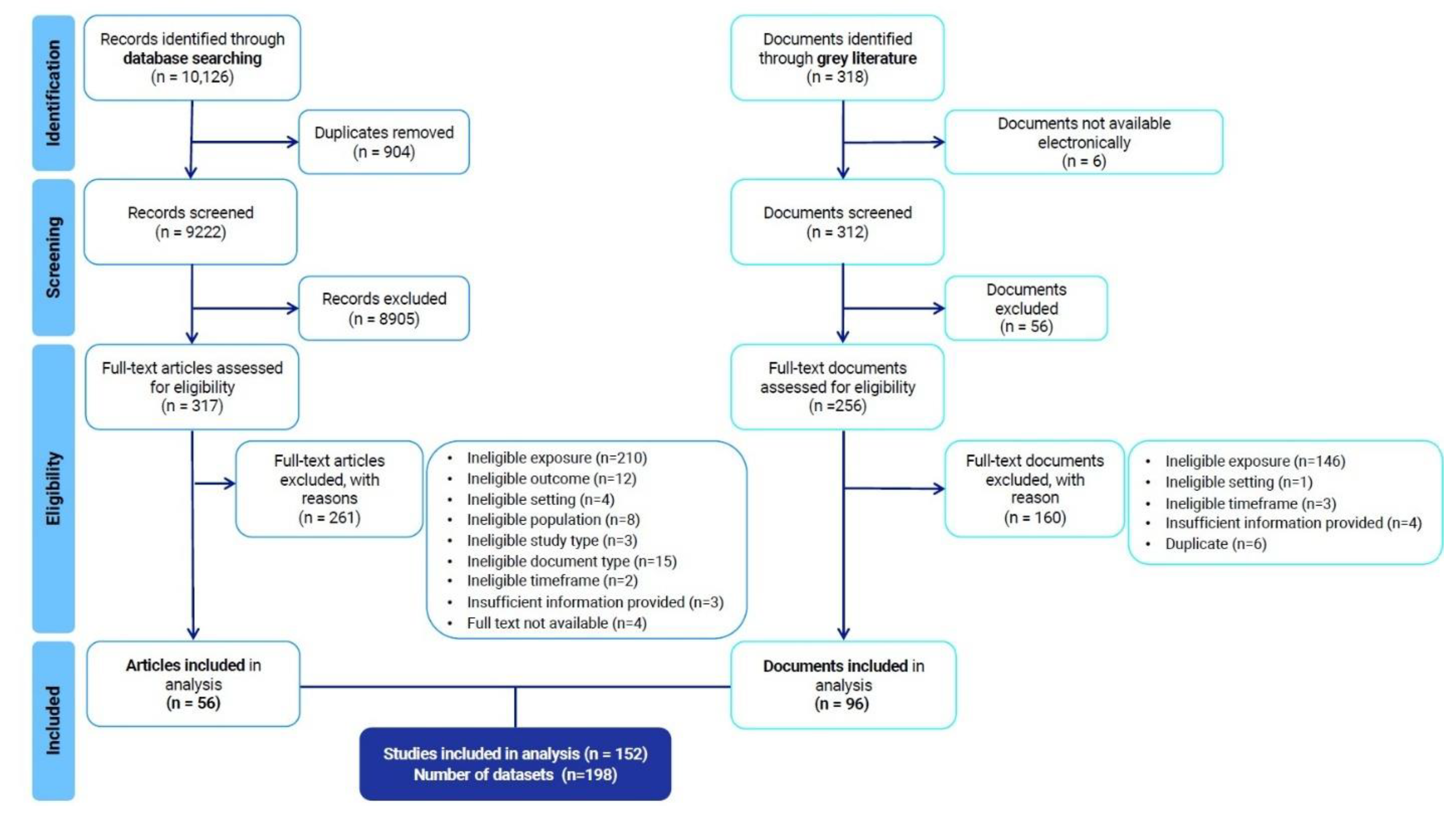

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Screening

2.3. Data Charting

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

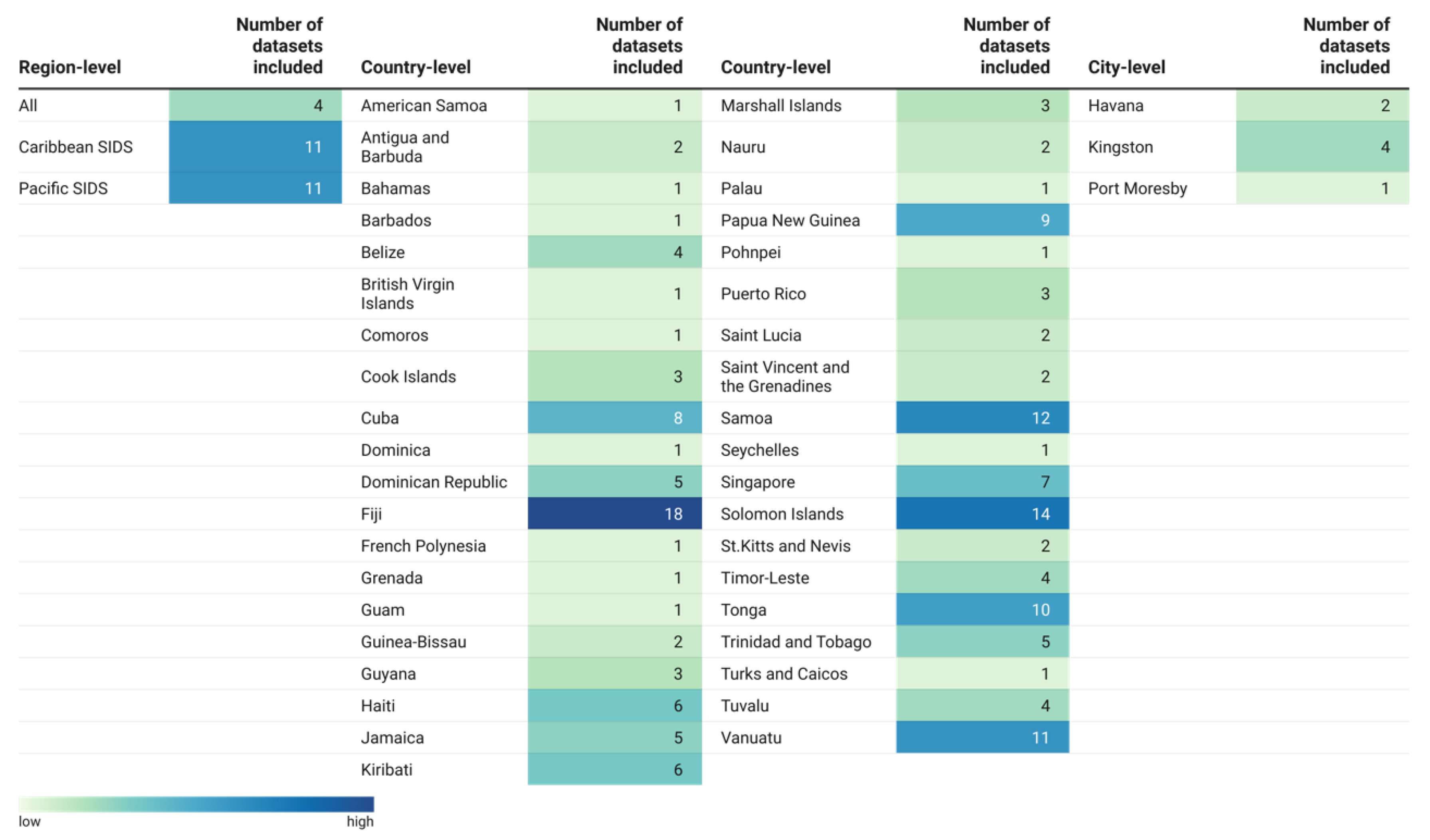

3.1. Geographic Coverage of Evidence

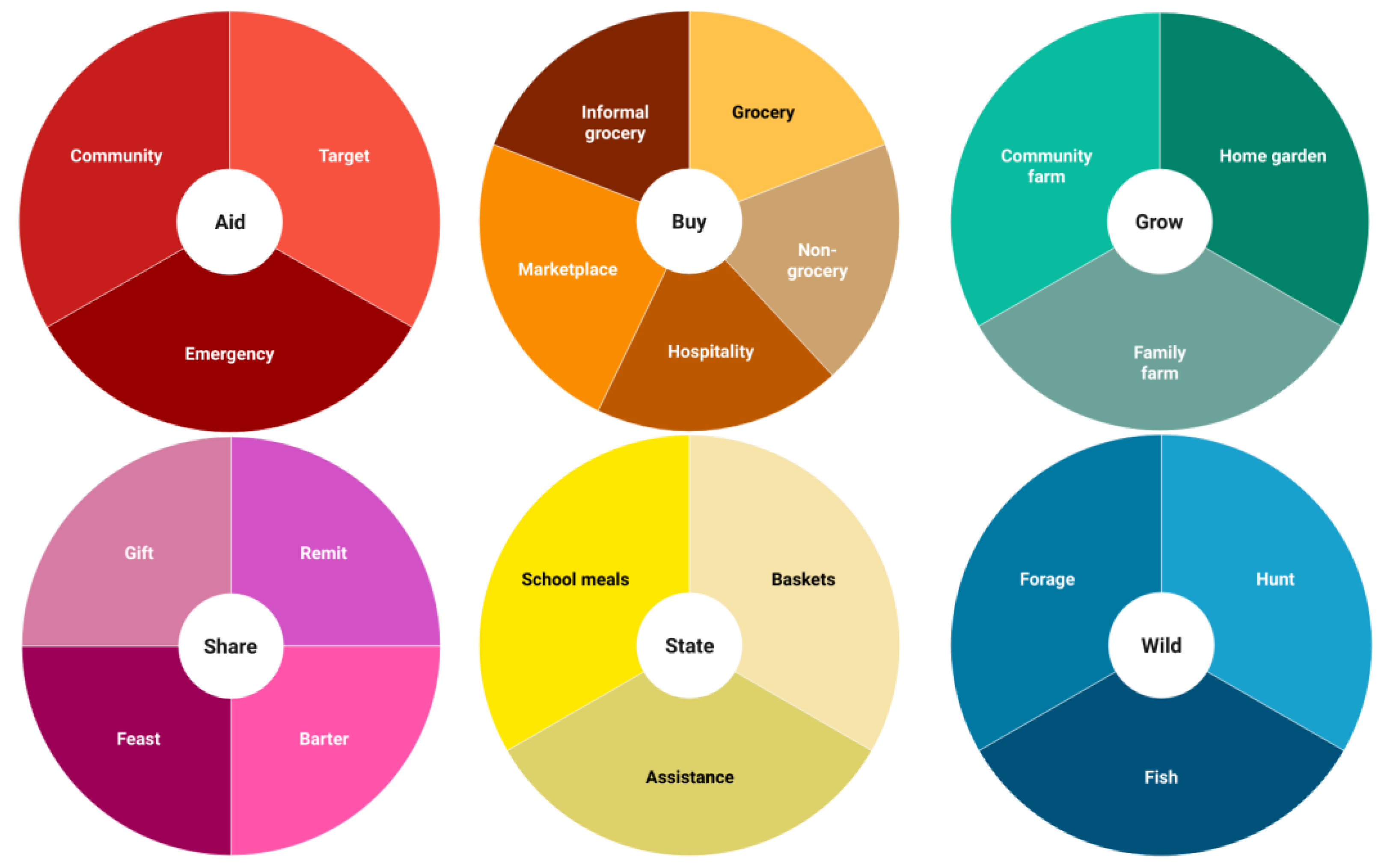

3.2. Our Proposed Classification of Food Sources Based on Evidence

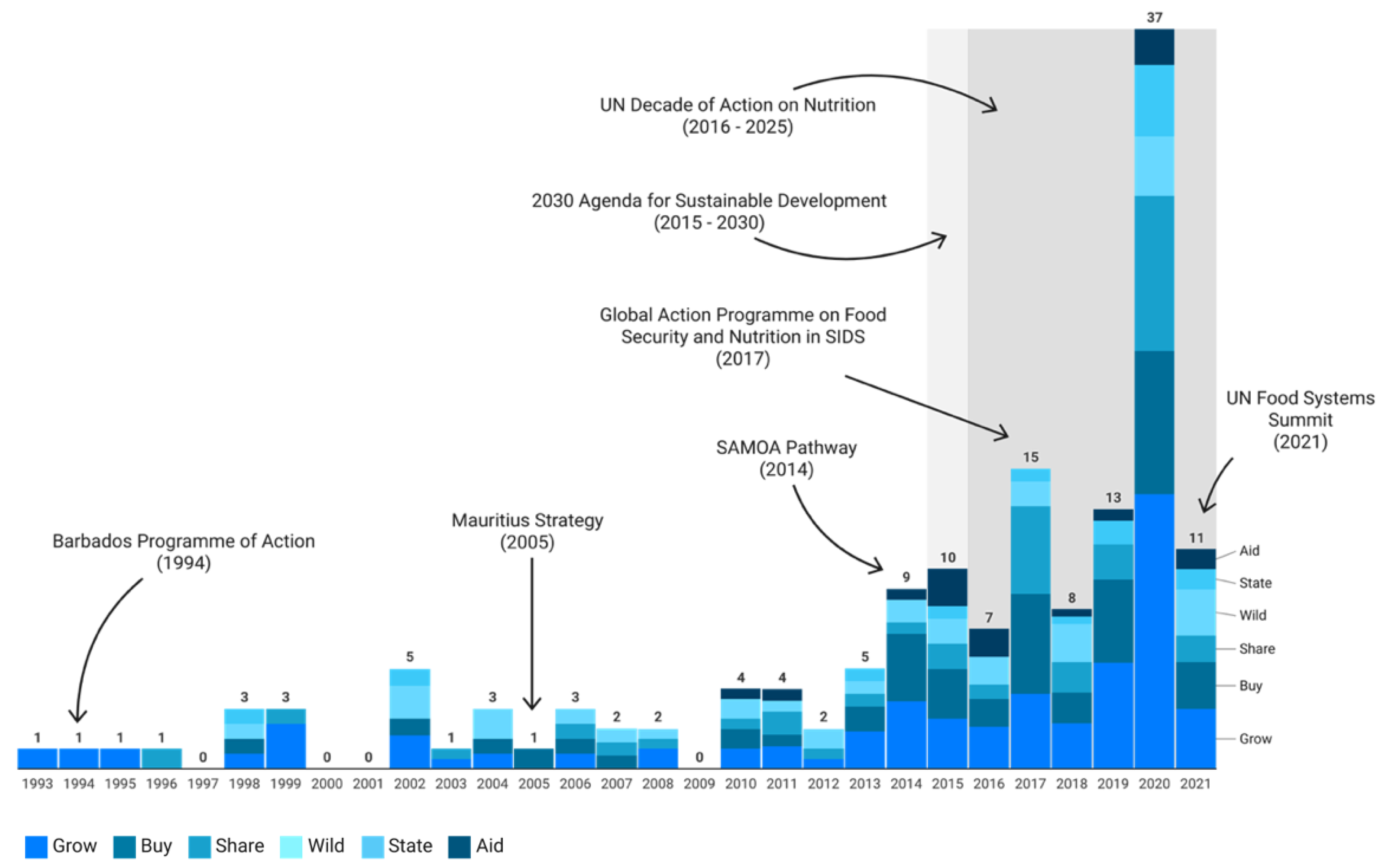

3.3. Changes in Food Sources over Time and Between Generations

3.4. Interconnections Between Food Sources

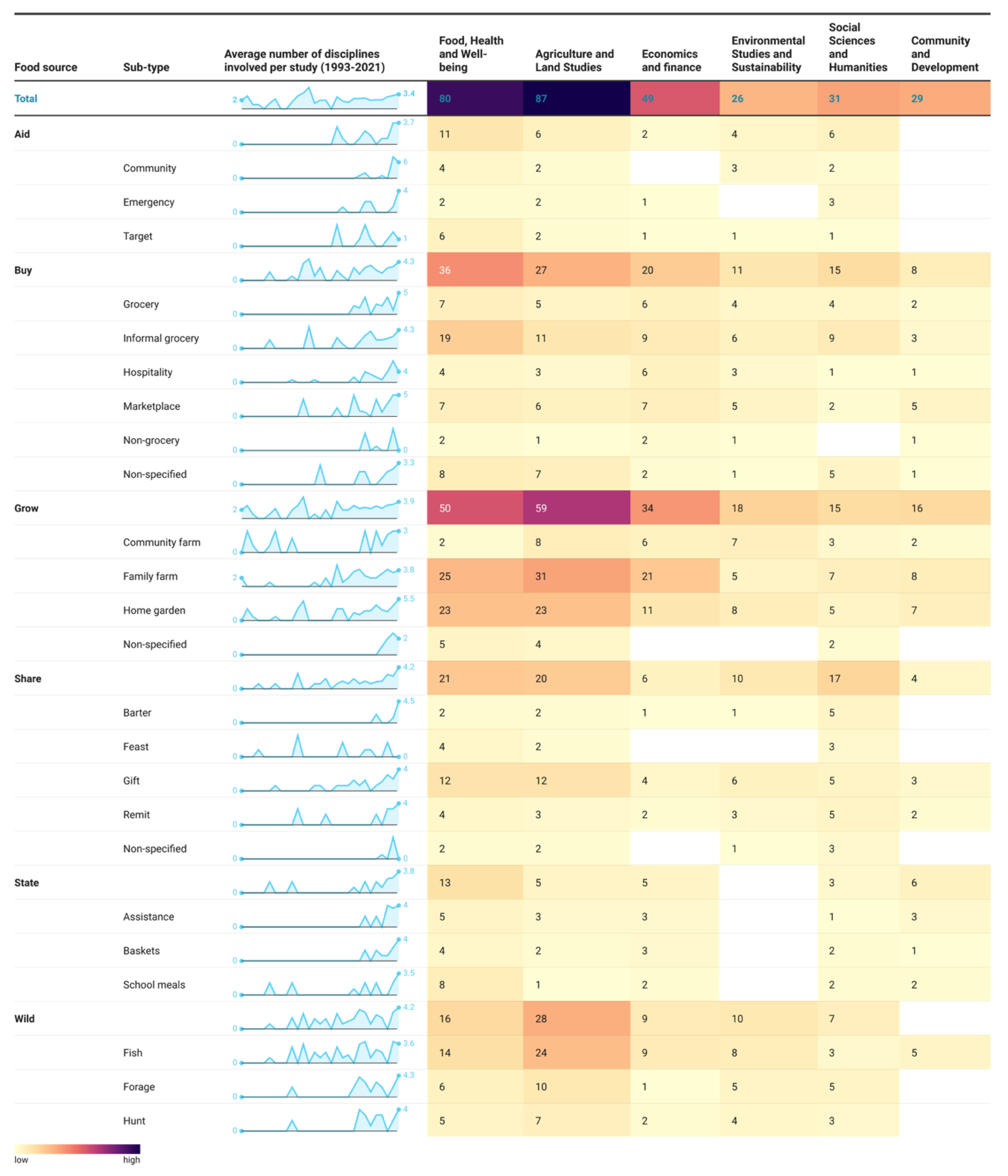

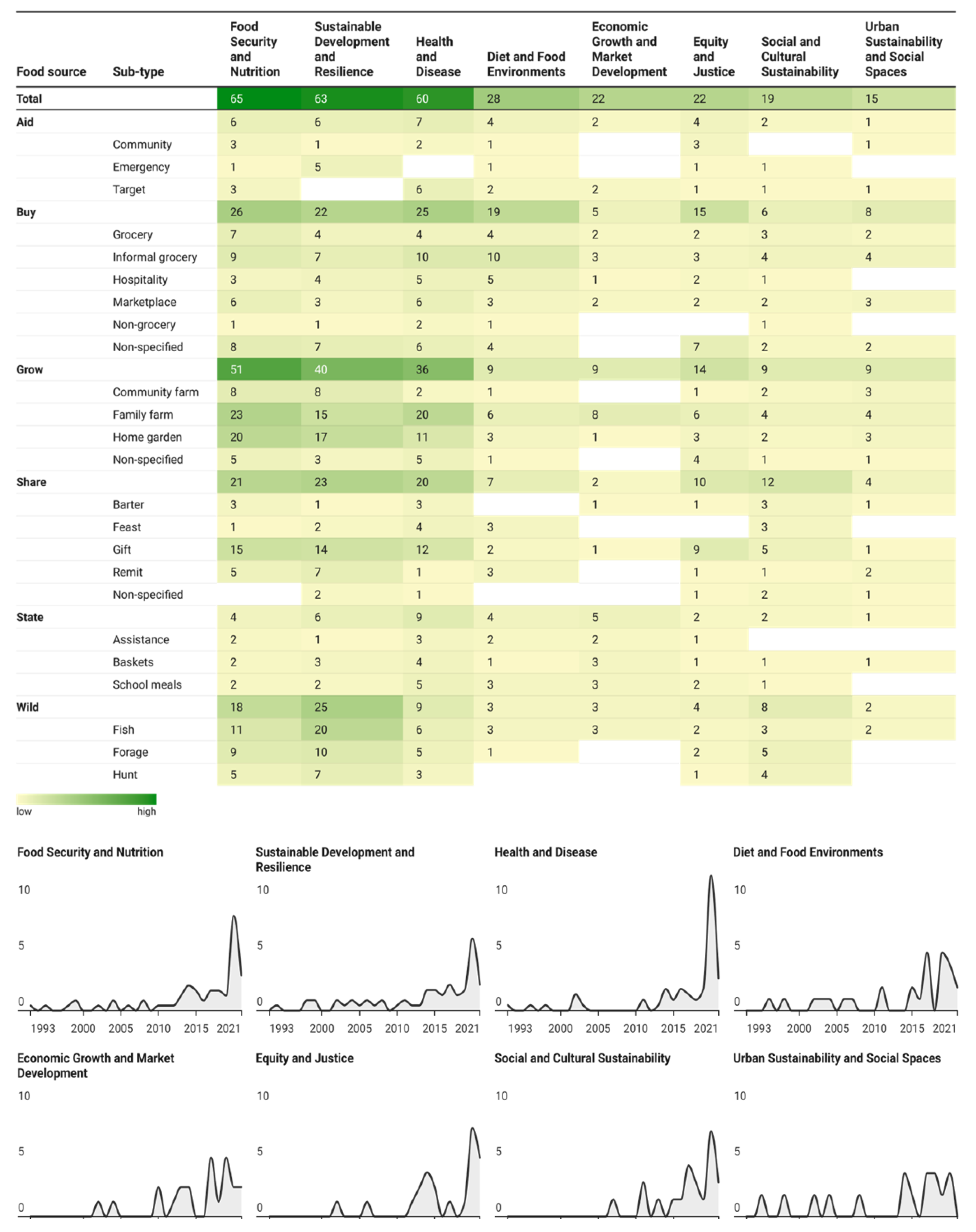

3.5. Extent of the Evidence

3.6. Conceptualisation of the Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Policy and Research Implications of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelman, I. Islandness within climate change narratives of small island developing states (SIDS). Isl. Stud. J. 2018, 13, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Action Programme on Food Security and Nutrition in Small Island Developing States. Policy Support and Governance. 2017. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i7427en (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IFPRI. Global Nutrition Report 2016 from Promise to Impact Ending Malnutrition by 2030. International Food Policy Research Institute. 2016. Available online: https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital/collection/p15738coll2/id/130354 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- The World Bank. Health, Non-Communicable Diseases. 2012. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/143531466064202659-0070022016/original/pacificpossiblehealthsummary.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Kalamatianou, S.; Drewnowski, A.; Kulkarni, B.; Kinra, S.; Kadiyala, S. Food Environment Research in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winson, A. Bringing political economy into the debate on the obesity epidemic. Agric. Hum. Values 2004, 21, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Aggarwal, A.; Walls, H.; Herforth, A.; Drewnowski, A.; Coates, J.; Kalamatianou, S.; Kadiyala, S. Concepts and critical perspectives for food environment research: A global framework with implications for action in low- and middle-income countries. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 18, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugulat-Panés, A.; Martin-Pintado, C.; Augustus, E.; Iese, V.; Guell, C.; Foley, L. OP08 The value of adding ‘grey literature’ in evidence syntheses for global health: A contribution to equity-driven research. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2022, 76, A4. [Google Scholar]

- Brugulat-Panés, A.; Martin-Pintado, C.; Guell, C.; Unwin, N.; Iese, V.; Augustus, E.; Foley, L. The value of adding ‘grey literature’ in evidence synthesis for equity-driven global health: A case study from Small Island Developing States. Unpublished work, currently under review. Unpublished work, currently under review.

- Haynes, E.; Bhagtani, D.; Iese, V.; Brown, C.R.; Fesaitu, J.; Hambleton, I.; Badrie, N.; Kroll, F.; Guell, C.; Brugulat-Panes, A.; et al. Food Sources and Dietary Quality in Small Island Developing States: Development of Methods and Policy Relevant Novel Survey Data from the Pacific and Caribbean. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagtani, D.; Augustus, E.; Haynes, E.; Iese, V.; Brown, C.R.; Fesaitu, J.; Hambleton, I.; Badrie, N.; Kroll, F.; Saint-Ville, A.; et al. Dietary patterns, food insecurity, and their relationships with food sources and social determinants in two small island developing states. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WTO. Legal Texts: The WTO Agreements. A Summary of the Final Act of the Uruguay Round. Available online: https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/ursum_e.htm#aAgreement (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Wentworth, C. Unhealthy Aid: Food Security Programming and Disaster Responses to Cyclone Pam in Vanuatu. Anthropol. Forum. 2020, 30, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Bourke, R.M. Planning Ahead to Reduce Feast and Famine After Natural Disasters. The Conversation. 2015. Available online: http://theconversation.com/planning-ahead-to-reduce-feast-and-famine-after-natural-disasters-42184 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Savage, A.; Bambrick, H.; Gallegos, D. Climate extremes constrain agency and long-term health: A qualitative case study in a Pacific Small Island Developing State. Weather. Clim. Extrem. 2021, 31, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO and Partners Help Restore Nutrition and Agricultural Livelihoods in the Pacific Islands. FAO Documents. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/638bf93a-a28e-4726-a8b7-eb7271258ff3 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Takasaki, Y. Targeting Cyclone Relief within the Village: Kinship, Sharing, and Capture. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2011, 59, 387–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WFP. Decentralized Evaluation. Final Evaluation of WFP Haiti’s Food for Education and Child Nutrition Programme (2016–2019). 2019. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000114311/download/?_ga=2.7872754.1344524560.1607531892-176607367.1607531892 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- WFP. Decentralized Evaluation. Final Evaluation of McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program in Guinea-Bissau. 2018. Available online: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000127754/download/?_ga=2.179077410.746154258.1713445281-1459940645.1712929966 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- CFS. Regional Initiatives. Pacific Food Summit. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/cfs/Docs0910/CFS36Docs/CFS36_Session_Presentations/CFS36_Agenda_Item_V_SWP_.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- WFP. Strengthening National Safety Nets. School Feeding: WFP’s Evolving Role in Latin America and the Caribbean. 2016. Available online: https://cdn.wfp.org/wfp.org/publications/strenghtening_national_safety_nets_school_feeding_wfp_evolving_role_in_lac.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- FAO. State of Food Insecurity in the CARICOM Caribbean. 2015. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/es?details=f21bbc91-da04-4014-936d-5dd90887c4df/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Thomas, K.; Rosenberger, J.G.; Pawloski, L.R. Food Security in Bombardopolis, Haiti. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2014, 9, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randin, G. COVID-19 and Food Security in Fiji: The Reinforcement of Subsistence Farming Practices in Rural and Urban Areas. Oceania 2020, 90, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Epps, J. Coping strategies, their relationship to weight status and food assistances food programs utilized by the food-insecure in Belize. In Proceedings of the 2015 5th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Technology, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 10–11 March 2015; Volume 81, pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- SHARECITY. Following Sustainable Food Narratives in Singapore. 2018. Available online: https://sharecity.ie/following-sustainable-food-narratives-in-singapore/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Iese, V.; Wairiu, M.; Hickey, G.M.; Ugalde, D.; Salili, D.H.; Walenenea, J.; Tabe, T.; Keremama, M.; Teva, C.; Navunicagi, O.; et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture and food systems in Pacific Island countries (PICs): Evidence from communities in Fiji and Solomon Islands. Agric. Syst. 2021, 190, 103099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAHO. Ultra-Processed Food and Drink Products in Latin America: Trends, Impact on Obesity, Policy Implications. Alimentos y Bebidas Ultraprocesados en América Latina: Tendencias, Efecto Sobre la Obesidad e Implicaciones Para las Políticas Públicas. 2015. Available online: https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/7699 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- IFAD. Transforming Rural Areas in Asia and the Pacific. 2014. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/knowledge/-/publication/transforming-rural-areas-in-asia-and-the-pacific (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Kinlocke, R.; Thomas-Hope, E.; Jardine-Comrie, A.; Timmers, B.; Ferguson, T.; Mccordic, C. The State of Household Food Security in Kingston, Jamaica; Hungry Cities Partnership: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/HCP15.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Thomas-Hope, E.; Kinlocke, R.; Ferguson, T.; Heslop-Thomas, C.; Timmers, B. The Urban Food System of Kingston, Jamaica; Hungry Cities Partnership: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://scholars.wlu.ca/hcp/4 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Johns, C.; Lyon, P.; Stringer, R.; Umberger, W. Changing urban consumer behaviour and the role of different retail outlets in the food industry of Fiji. Asia-Pac. Dev. J. 2017, 24, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogliano, C.; Raneri, J.E.; Coad, J.; Tutua, S.; Wham, C.; Lachat, C.; Burlingame, B. Dietary agrobiodiversity for improved nutrition and health outcomes within a transitioning indigenous Solomon Island food system. Food Sec. 2021, 13, 819–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra Mallol, C. Monetary income, public funds, and subsistence consumption: The three components of the food supply in French Polynesia—A comparative study of Tahiti and Rapa Iti islands. Rev. Agric. Food Environ. Stud. 2018, 99, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. CARICOM Food Import Bill, Food Security and Nutrition. FAO Documents. 2013. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d11d9db6-8c12-438e-aec2-08e6c6fd3a20/content (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- CGIAR. From Happy Hour to Hungry Hour: Logging, Fisheries and Food Security in Malaita, Solomon Islands. 2018. Available online: https://www.cgiar.org/research/publication/happy-hour-hungry-hour-logging-fisheries-food-security-malaita-solomon-islands/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Chong, M.; Hinton, L.; Wagner, J.; Zavitz, A. An Urban Perspective on Food Security in the Global South; Hungry Cities Partnership: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2018; Available online: https://hungrycities.net/policy-brief/an-urban-perspective-on-food-security-in-the-global-south/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Burkhart, S. The Role of Diets and Food Systems in the Prevention of Obesity and Non-Communicable Diseases in Fiji: Gathering Evidence and Supporting Multi-Stakeholder Engagement; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliata, T.; Asem, P.; Levi, J.; Iosua, T.; Ioane, A.; Seupoai, V.; Eteuati, M.; Solipo, P.; Nuu, T.; Boodoosingh, R. Capturing the Experiences of Samoa: The Changing Food Environment and Food Security in Samoa during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Oceania 2020, 90, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCubbin, S.G.; Pearce, T.; Ford, J.D.; Smit, B. Social—Ecological change and implications for food security in Funafuti, Tuvalu. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippert, C. The moral economy of corner stores, buying food on credit, and Haitian-Dominican interpersonal relations in the Dominican Republic. Food Foodways 2017, 25, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, J.R. Changing consumption, changing tastes? Exploring consumer narratives for food secure, sustainable and healthy diets. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 53, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narine, T.; Badrie, N. Influential Factors Affecting Food Choices of Consumers When Eating Outside the Household in Trinidad, West Indies. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2007, 13, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Using Mixed Methods to Describe a Spatially Dynamic Food Environment in Rural Dominican Republic. Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G. Growing Greener Cities in Latin America and the Caribbean: An FAO Report on Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture in the Region; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morshed, A.B.; Becker, H.V.; Delnatus, J.R.; Wolff, P.B.; Iannotti, L.L. Early nutrition transition in Haiti: Linking food purchasing and availability to overweight status in school-aged children. Public. Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 3378–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Cacavas, K.; Mavoa, H.; Kremer, P.; Malakellis, M.; Fotu, K.; Swinburn, B.; de Silva-Sanigorski, A. Tongan Adolescents’ Eating Patterns: Opportunities for Intervention. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2011, 23, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinlocke, R.; Thomas-Hope, E. Inclusive Growth and the Informal Food Sector in Kingston, Jamaica; Hungry Cities Partnership: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/HCP19.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Barbados Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; PAHO; UNICEF; WFP. Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition—Latin America and the Caribbean 2022: Towards Improving Affordability of Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy; IFAD: Rome, Italy; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fisheries of the Pacific Islands. Regional and National Information. 2018. Available online: https://pacific-data.sprep.org/system/files/fisheries-pacific-2018.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- FAO. Enhancing Evidence-Based Decision Making for Sustainable Agriculture Sector Development in Pacific Islands Countries. FAO Documents. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/zh?details=2a39b2bc-e27b-5246-8c15-41e9469a330b/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- FAO. COVID-19 and the Role of Local Food Production in Building More Resilient Local Food Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Documentation of the Traditional Food System of Pohnpei. 2009. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i0370e/i0370e07.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- WFP. Adolescent Nutrition in Timor-Leste. A Formative Research Study. 2019. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/publications/2019-timor-leste-adolescent-nutrition (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Walker, S.P.; Powell, C.A.; Hutchinson, S.E.; Chang, S.M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.M. Schoolchildren’s diets and participation in school feeding programmes in Jamaica. Public Health Nutr. 1998, 1, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHARECITY. Summer Edition: Food in Cuba! 2019. Available online: https://sharecity.ie/food-in-cuba/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Hidalgo, D.M.; Witten, I.; Nunn, P.D.; Burkhart, S.; Bogard, J.R.; Beazley, H.; Herrero, M. Sustaining healthy diets in times of change: Linking climate hazards, food systems and nutrition security in rural communities of the Fiji Islands. Reg. Environ. Change 2020, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Regional Summary Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/publications/caribbean-covid-19-food-security-livelihoods-impact-survey-round-1 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- SHARECITY. Thank You Food Sharers of Singapore! 2017. Available online: https://sharecity.ie/thank-food-sharers-singapore/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Bottcher, C.; Underhill, S.J.R.; Aliakbari, J.; Burkhart, S.J. Food Access and Availability in Auki, Solomon Islands. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Healthy Marketplaces in the Western Pacific: Guiding Future Action. Applying a Settings Approach to the Promotion of Health in Marketplaces. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9290611707 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- UN Women. Gordons Market, Port Moresby Officially Opens. Asia-Pacific. 2019. Available online: https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/news-and-events/stories/2019/11/gordons-market (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- UN Women. Making Markets Safe for Women Vendors in Papua New Guinea. 2014. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2014/4/new-zealand-increases-funding-for-safe-city-programme-in-png (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Mele, C.; Ng, M.; Chim, M.B. Urban markets as a ‘corrective’ to advanced urbanism: The social space of wet markets in contemporary Singapore. Urban. Stud. 2015, 52, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The Right to Food in the CARICOM Region: An Assessment Report. The Right to Food. 2013. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/i3271e/i3271e.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Smith, D. The relational attributes of marketplaces in post-earthquake Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Environ. Urban. 2019, 31, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, C.; Underhill, S.J.; Aliakbari, J.; Burkhart, S.J. Food purchasing behaviors of a remote and rural adult Solomon islander population. Foods 2019, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Belize Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hongjun, W. Food and the Singapore young consumer. Young Consum. 2006, 7, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, N.; van Dam, R.M.; Ng, S.; Tan, C.S.; Chen, S.; Lim, J.Y.; Chan, M.F.; Chew, L.; Rebello, S.A. Determinants of eating at local and western fast-food venues in an urban Asian population: A mixed methods approach. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadi, M.A. Restaurant Patronage and the Ethnic Groups in Singapore: An Exploratory Investigation Using Barker’s Model. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2002, 5, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity into Agricultural Production and Management in the Pacific Islands: Technical Guidance Document; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IFAD. Enabling Poor Rural People to Overcome Poverty in Seychelles. 2013. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/knowledge/-/publication/enabling-poor-rural-people-to-overcome-poverty-in-seychelles (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Rosset, P.; Benjamin, M. Two Steps Back, One Step Forward: Cuba’s National Policy for Alternative Agriculture; International Institute for Environment and Development; Sustainable Agriculture Programme; IIED: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, L.A.; Harder, A.M.; Henry, C.V.; Ganpat, W.G.; Martin, E. Factors That Influence Engagement in Home Food Production: Perceptions of Citizens of Trinidad. J. Agric. Educ. 2017, 58, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, M.D.; Lopes, M.; Ximenes, A.; Ferreira, A.D.R.; Spyckerelle, L.; Williams, R.; Nesbitt, H.; Erskine, W. Household food insecurity in Timor-Leste. Food Sec. 2013, 5, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAO and SIDS: Challenges and Emerging Issues in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. In Proceedings of the Inter-Regional Conference of Small Island Developing States, Nassau, Bahamas, 26–30 January 2004; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thaman, R.R. Urban food gardening in the Pacific Islands: A basis for food security in rapidly urbanising small-island states. Habitat. Int. 1995, 19, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Moroca, A.; Bhat, J.A. Neo-traditional approaches for ensuring food security in Fiji Islands. Environ. Dev. 2018, 28, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valstar, A. Home-Based Food Production in Urban Jamaica. FAO. 1999. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/x2650T/x2650t08.htm#:~:text=Home%20gardening%20often%20provides%20a,as%20well%20as%20rural%20communities (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- PFAO. Pacific Islands and FAO Achievements and Success Stories. 2011. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/au193e/au193e.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Hibi, E.; Lam, F.; Chopin, F. Accelerating Action on Food Security and Nutrition in Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Agribusiness. Urban and Peri-urban Agriculture in Latin America and the Caribbean. Antigua and Barbuda. 2014. Available online: https://agricarib.org/antigua-barbuda-2/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- WHO. Diet, Food Supply and Obesity in the Pacific. 2003. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/206945/9290610441_eng (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Craven, L.K.; Gartaula, H.N. Conceptualising the Migration–Food Security Nexus: Lessons from Nepal and Vanuatu. Aust. Geogr. 2015, 46, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Trinidad and Tobago Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Jamaica Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Bahamas Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihood Impact Survey—Grenada Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—British Virgin Islands Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Hope, E.; Kinlocke, R.; Ferguson, T. Enhancing Food Security Through Urban Agriculture in Kingston, Jamaica; Hungry Cities Partnership: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2010; Available online: https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/HCPbrief9.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Garcia-Montiel, D.C.; Verdejo-Ortiz, J.C.; Santiago-Bartolomei, R.; Vila-Ruiz, C.P.; Santiago, L.; Melendez-Ackerman, E. Food sources and accessibility and waste disposal patterns across an urban tropical watershed: Implications for the flow of materials and energy. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Panorama of Food and Nutritional Security in Latin America and the Caribbean; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lucantoni, D. Transition to agroecology for improved food security and better living conditions: Case study from a family farm in Pinar del Río, Cuba. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 44, 1124–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iimi, A. Hidden Treasures in the Comoros: The Impact of Inter-Island Connectivity Improvement on Agricultural Production; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Security and Nutrition in Small Island Developing States (SIDS); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Improving the Capacity of Farmers to Market a Consistent Supply of Safe, Quality Food—TCP/SAM/3601; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Dominica Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Agriculture for Growth: Learning from Experience in the Pacific. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/282556/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Rodríguez, D.I.; Anríquez, G.; Riveros, J.L. Food security and livestock: The case of Latin America and the Caribbean. Cienc. Investig. Agrar. 2016, 43, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP; Kitts, S. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—St.Kitts and Nevis Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Saint Lucia Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Blue Growth Initiative and Small Island Developing States (SIDS); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sherzad, S. Family Farming in the Pacific Islands Countries: Challenges and Opportunities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reti, M.J. A Case Study in the Republic of the Marshall Islands—An Assessment of the Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Food Security in the Pacific; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. An Assessment of the Impact of Climate Change on Agriculture and Food Security in the Pacific. A Case Study in the Cook Islands. 2008. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/288433/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Sharma, K.L. Food Security in the South Pacific Island Countries with Special Reference to the Fiji Islands. In Food Insecurity, Vulnerability and Human Rights Failure; Guha-Khasnobis, B., Acharya, S.S., Davis, B., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007; pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Roundtable on the Competitiveness of Pacific Island Small and Medium Agro-Processing Enterprises. FAO Documents. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/fr?details=1e25eff1-32b2-5a09-b7ca-668a5bd6f73b/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Bryceson, K.P.; Ross, A. Agrifood chains as complex systems and the role of informality in their sustainability in small scale societies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogliano, C.; Raneri, J.E.; Maelaua, J.; Coad, J.; Wham, C.; Burlingame, B. Assessing diet quality of indigenous food systems in three geographically distinct solomon islands sites (Melanesia, Pacific Islands). Nutrients 2020, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, G.; Lyons, G.; Edis, R. How food gardens based on traditional practice can improve health in the Pacific. The Conversation. 2017. Available online: http://theconversation.com/how-food-gardens-based-on-traditional-practice-can-improve-health-in-the-pacific-75858 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Opio, F. Contribution of subsistence diets to farm household nutrient requirements in the pacific. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1993, 29, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission (CFSAM) to the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Strengthened Household Agroforestry and Food Production in Nauru—TCP/NAU/3501; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, A.; Bambrick, H.; Gallegos, D. From garden to store: Local perspectives of changing food and nutrition security in a Pacific Island country. Food Sec. 2020, 12, 1331–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFAD. Investing in Rural People in Papua New Guinea. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/knowledge/-/publication/investing-in-rural-people-in-papua-new-guinea (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- WFP. Caribbean COVID-19 Food Security, Livelihoods Impact Survey—Guyana Summary Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- IFAD. Investing in Rural People in Guinea-Bissau. 2019. Available online: https://www.ifad.org/en/web/knowledge/-/publication/investing-in-rural-people-in-guinea-bissau (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Chaplowe, S.G. Havana’s popular gardens:sustainable prospects for urban agriculture. Environmentalist 1998, 18, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlvaine-Newsad, H.; Porter, R.; Delany-Barmann, G. Change the game, not the rules: The role of community gardens in disaster resilience. J. Park. Recreat. Adm. 2020, 38, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskow, A. Havana’s Self-Provision Gardens. Environment and Urbanization. 1999. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Havana%27s+self-provision+gardens&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Maryanne Grieg-Gran, I.G. Local Perspectives on Forest Values in Papua New Guinea—The Scope for Participatory Methods. Available online: https://www.iied.org/6155iied (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Altieri, M.A.; Companioni, N.; Cañizares, K.; Murphy, C.; Rosset, P.; Bourque, M.; Nicholls, C.I. The greening of the “barrios”: Urban agriculture for food security in Cuba. Agric. Human. Values 1999, 16, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Moulton, A.A.; Barker, D.; Malcolm, T.; Scott, L.; Spence, A.; Tomlinson, J.; Wallace, T. Wild Food Harvest, Food Security, and Biodiversity Conservation in Jamaica: A Case Study of the Millbank Farming Region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 663863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RUAF. Enhancing the Contribution of Urban Agriculture to Food Security. 2002. Available online: https://ruaf.org/document/urban-agriculture-magazine-enhancing-the-contribution-of-urban-agriculture-to-food-security/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Gillett, R.; Moy, W.; Fishery and Aquaculture Economics and Policy Division. Report of the FAO/SPC Pacific Islands Regional Consultation on the Development of Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries, Noumea, New Caledonia, 12–14 June 2012. FAO. 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/i3063e (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- García-Quijano, C.G.; Lloréns, H. What Rural, Coastal Puerto Ricans Can Teach Us About Thriving in Times of Crisis. The Conversation. 31 May 2017. Available online: http://theconversation.com/what-rural-coastal-puerto-ricans-can-teach-us-about-thriving-in-times-of-crisis-76119 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- SHARECITY. Singapore. 2017. Available online: https://sharecity.ie/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Singapore-final.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Troubat, N.; Faaola, E.; Aliyeva, R. Food Security and Food Consumption in Samoa: Based on the Analysis of the 2018 Household Income and Expenditure Survey; FAO: Rome, Italy; SBS: Apia, Samoa, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Marine Fishery Resources of the Pacific Islands. 2010. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i1452e/i1452e00.htm#:~:text=Oceanic%20or%20offshore%20resources%20include,and%20potentially%20extensive%20individual%20movements (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- FAO; SPC. Solomon Islands Food Security Profile; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Tonga: Food Security Profile; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, A. Changes in social orientation: Threats to a cultural institution in marine resource exploitation in Tonga. Human. Organ. 2007, 66, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, D. Family relationships in town are brokbrok: Food sharing and “contribution” in Port Vila, Vanuatu. J. Société Océanistes 2017, 144-145, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knso, F. Kiribati Food Security Profile; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Pacific Community, Tuvalu Central Statistics Division. In Tuvalu Food Security Profile; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tora, T. Two Piglets for a Kayak: Fiji Returns to Barter System as COVID-19 Hits Economy. The Guardian. 2020. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/08/two-piglets-for-a-kayak-fiji-returns-to-barter-system-as-covid-19-hits-economy (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Siutaia, H. Le Barter Trading Platform Glimpse of the Past. Samoa Observer. 2020. Available online: https://www.samoaobserver.ws/category/samoa/62224 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Boodoosingh, R. Bartering in Samoa During COVID-Devpolicy Blog from the Development Policy Centre. 2020. Available online: https://devpolicy.org/bartering-in-samoa-during-covid-19-2020630-1/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Maeir, A.M. A Feast in Papua New Guinea. Near Eastern Archaeology. 2015. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5615/neareastarch.78.1.0026 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Wentworth, C. Public eating, private pain: Children, feasting, and food security in Vanuatu. Food Foodways 2016, 24, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, Y.C.; Guerrero, R.T.L. Women in Guam consume more calories during feast days than during non-feast days. Micronesica 2011, 41, 223–235. [Google Scholar]

- Lako, J.V.; Nguyen, V.C. Dietary patterns and risk factors of diabetes mellitus among urban indigenous women in Fiji. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 10, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP. Smart School Meals: Nutrition-Sensitive National Programmes in Latin America and the Caribbean—A Review of 16 Countries. Reliefweb. 2017. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/smart-school-meals-nutrition-sensitive-national-programmes-latin-america-and-0 (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Reeser, D.C. “They don’t garden here”: NGO constructions of Maya gardening practices in Belize. Dev. Pract. 2013, 23, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beazley, R.; Ciardi, F.; Bailey, S. Shock Responsive Social Protection in the Caribbean—Synthesis Report; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, S.; Ciardi, F. Shock-Responsive Social Protection in the Caribbean. In Guyana Case Study; WFP: Rome, Italy,, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford, M.C.; Mahabir, D.; Rocke, B.; Chinn, S.; Rona, R.J. Free school meals and children’s social and nutritional status in Trinidad and Tobago. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.; Ciardi, F. Shock-Responsive Social Protection in the Caribbean. Belize Case Study; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Strengthening the Capacity of Farmers and Food Vendors to Supply Safe Nutritious Food in Guadalcanal, Malaita and Temotu Provinces of Solomon Islands—TCP/SOI/3601; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CARPHA. Healthy Ageing in the Caribbean. State of Public Health Report. 2019. Available online: https://caricom.org/documents/state-of-public-health-report-2019/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Burkhart, S. School Nutrition Education Programmes in the Pacific Islands: Scoping Review and Capacity Needs Assessment: Final Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, W.; Ximenes, A.; Glazebrook, D.; da Costa, M.; Lopes, M.; Spyckerelle, L.; Williams, R.; Nesbitt, H. The role of wild foods in food security: The example of Timor-Leste. Food Sec. 2015, 7, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Natural Resources Management and the Environment in Small Island Developing States (SIDS); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Forest and Forestry in Small Island Developing States. 2002. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/y8222e/y8222e00.htm (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Thomas, A.; Mangubhai, S.; Fox, M.; Meo, S.; Miller, K.; Naisilisili, W.; Veitayaki, J.; Waqairatu, S. Why they must be counted: Significant contributions of Fijian women fishers to food security and livelihoods. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 205, 105571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.S.; Claar, D.C.; Baum, J.K. Subsistence in isolation: Fishing dependence and perceptions of change on Kiritimati, the world’s largest atoll. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2016, 123, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation in the CARICOM and Wider Caribbean Region. 2015. Available online: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/es?details=c536061f-aeb0-4881-9506-60c0226b7e52/ (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- FAO. Management of Large Pelagic Fisheries in CARICOM Countries. 2004. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/y5308e/y5308e00.htm (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- David, G. Village fisheries in the Pacific Islands. In Proceedings of the Soeio-Eeonomies, Innovation and Management of the Java Sea Pelagie Fisheries, Bandungan, Indonesia, 4–7 December 1995; p. 63. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers09-03/010017888.pdf#page=64 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Gillett, R.; Moy, W. Fishery and Aquaculture Economics and Policy Division. Spearfishing in the Pacific Islands. Current Status and Management Issues; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson, K.P.; Ross, A. Habitus of informality in small scale society agrifood chains—Filling the knowledge gap using a socio-culturally focused value chain analysis tool. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2020, 25, 545–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Barbados Programme of Action. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. 1994. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=13&nr=365&menu=1016 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UN. Mauritius Strategy of Implementation. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. 2005. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/conferences/msi2005 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UN-OHRLLS. The SAMOA Pathway. 2014. Available online: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/content/samoa-pathway (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UN. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UNSCN. The Decade of Action on Nutrition 2016–2025. 2016. Available online: https://www.unscn.org/en/topics/un-decade-of-action-on-nutrition (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UN. Food Systems Summit. 2021. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/food-systems-summit (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, P.; Rotmans, J. Transitions in a globalising world. Futures 2005, 37, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIG OCEAN STATES at COP27. 2022. Available online: https://www.sciencespo.fr/psia/chair-sustainable-development/2022/11/21/big-ocean-states-at-cop27/ (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Forum, S. Recognizing Large Ocean States for Better Development Support. 2022. Available online: https://siprforum.medium.com/recognizing-large-ocean-states-for-better-development-support-9a7fad1695e4 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Hume, A.; Leape, J.; Oleson, K.L.; Polk, E.; Chand, K.; Dunbar, R. Towards an ocean-based large ocean states country classification. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Pacific NCD Hub. What’s In A Name? SIDS Or BOSS? 2021. Available online: https://pacificndc.org/articles/whats-name-sids-or-boss (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Chan, N. “Large Ocean States”: Sovereignty, Small Islands, and Marine Protected Areas in Global Oceans Governance. In Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellsmoor, J. Small Island States or Large Ocean Nations?|Green. Caribbean Beat Magazine. 2023. Available online: https://www.caribbean-beat.com/issue-175/small-island-states-or-large-ocean-nations-green (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UN-OHRLLS. Small Island Developing States In Numbers 2020—Oceans Edition Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States. 2020. Available online: https://www.un.org/ohrlls/news/small-island-developing-states-numbers-2020-oceans-edition (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- UNESCO. Safeguarding Precious Resources for Island Communities. 2014. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000228833 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

| Sub-Type (Type) | Summary Description | Location and Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency (Aid) | Reported as immediate short-term assistance during and after disasters, such as extreme weather events. Typically provided by foreign governments, international organisations, humanitarian agencies or philanthropic organisations. Commonly reported foods consisted of imported dry and shelf-stable products such as instant noodles, rice, flour, biscuits, and tinned meats and fish (see Supplementary Materials for a classification of food items by food group). While it played a crucial role in alleviating hunger and increasing food access and availability of a few food items, these were reported to contradict public health messages on healthy diets [16]. Particularly impactful for populations affected by climate extremes, especially agricultural-dependent families facing significant losses due to the reliance on garden produce for subsistence. | Vanuatu [16,17,18,19], Fiji [20]. |

| Target (Aid) | Described as food aid provided by foreign donors that additionally supported existing national programmes and local initiatives for a longer period compared to Emergency. Reported foods included a mix of local and imported items like cereals, pulses, nuts, and vegetable seedlings, serving as a safety net addressing short-term hunger, increasing household food income, children’s school attendance, and access to nutrient-rich food. Despite this, it was reported to lack food diversity and not meet the food energy requirements [21]. Commonly reported as relevant for individuals suffering from severe malnutrition and disease, including food-insecure primary school children. However, it was reported to struggle to reach the most disadvantaged children from the poorest and most vulnerable communities [22]. | Pacific region [23], Cuba [24], Dominican Republic [24], Haiti [21,24,25,26], Guinea-Bissau [22], Fiji [27]. |

| Community (Aid) | Reported as food aid funded by locally based non-governmental organisations, charities, social enterprises, churches, and voluntary groups. Often relied on volunteer donations and included initiatives such as providing meals during school holidays to children in need, and health awareness activities [28]. This type of aid was reported to provide some fresh meat and vegetables in addition to food staples. It played diverse roles, from improving food security to mental well-being, nutrition and health education. It was especially important for those individuals facing food insecurity [26], and addressing feelings of loneliness and social isolation across various income levels [29]. | Singapore [29], Fiji [13,30], Solomon Islands [30], Haiti [26], Belize [28], Saint Vincent and the Grenadines [13]. |

| Grocery (Buy) | Referred to by the evidence as ‘hypermarket’, ‘supermarket’, ‘big-box style supermarket’, ‘modern convenience store’ and ‘Western-style grocery store’. Described as modern stores, often owned by multinational corporations. These establishments, supplied by wholesalers, were reported to offer a wider range of food items, albeit at higher prices [31,32]. While grocery stores were described as providing convenience and bulk purchasing options, they were visited less frequently, possibly due to the practice of monthly bulk purchases influenced by discount offers [33,34]. Positively associated with higher reported intakes of fruit and vegetables and greater dietary diversity, as well as increased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, red and processed meats [13]. Described as the preferred choice for purchasing processed and manufactured food products [35]. They were reported to symbolise status and modernity, offering imported foods associated with affluence and convenience [36,37]. Especially relevant for high-income households. | Caribbean region [31,38], Solomon Islands [30,36,39], Pacific region [32], Kingston (Jamaica) [33,34], Jamaica [40], Fiji [30,35,41], French Polynesia [37], Samoa [42], Tuvalu [43], Dominican Republic [44], Turks and Caicos [45], Trinidad [46], Saint Vincent and the Grenadines [13]. |

| Informal grocery (Buy) | Referred to by the evidence as ‘street-food vendor’, ‘corner shop’, ‘food truck’, ‘colmado’ (term used in evidence from the Dominican Republic which refers to a mix between a small supermarket and a bar), ‘small shop’, ‘roadside stationery’, and ‘itinerant stall’. Generally reported as having a decentralised structure with various suppliers, transporters, and vendors, predominantly comprised of small, family-owned businesses with minimal capital investment. Despite potential limitations in stock and pricing, these establishments were reported to offer proximity, monthly credit facilities, and convenience [35,44,47,48], often concentrating in commercial hubs and adapting to consumer needs with flexibility [34,49,50]. Vendors were described as adapting to the socio-economic conditions of their clientele by selling food in smaller portions, thus making goods more affordable. Also, they adopted customer-friendly practices to cultivate loyalty by including extra portions at no charge or by providing credit [33,44,51]. This food source was reported to play an important role in ensuring food security for poor urban households and remote rural villages without access to transportation [42,52], while also serving as a source of income for women vendors [23,53]. Described as offering a wide range of foods from local fresh produce to bulk products such as rice and beans, to packaged snacks, soft drinks, sauces, and canned processed foods. | Pacific region [23,54], Caribbean region [31,53], Kiribati [55], Samoa [42,55], Solomon Islands [55], Vanuatu [55,56], Pohnpei [57], Barbados [52], Timor-Leste [58], Kingston (Jamaica) [33,34,51], Jamaica [40,59], Cuba [60], Fiji [35,41,61], Havana (Cuba) [48], Belize [28], Haiti [49], French Polynesia [37], Tonga [50,55], Dominican Republic [30,44,47], Turks and Caicos [45], Trinidad [46]. |

| Non-grocery (Buy) | Referred to by the evidence as ‘pharmacy’, ‘bookstore’, ‘gas station’, ‘internet retail’, and ‘door-to-door retail’. It was reported to offer limited selections of ultra-processed foods and drink products, with online retail playing a minor role, and primarily used during COVID by the at-risk population to avoid crowds in stores [31,62,63]. | Caribbean region [31,62], Singapore [63]. |

| Marketplace (Buy) | Referred to by the evidence as ‘central market’, ‘domestic market’, ‘local market’, ‘municipal market’, ‘town market’, ‘city market’, ‘formal market’, ‘wet market’, ‘fish market’ and ‘farmer market’. Marketplaces were reported to feature stalls with various fresh produce and spices [33,41,64]. Despite challenges like poor sanitation and vendor vulnerability [34,65,66,67], these markets were described as perceived providers of fresher and healthier options due to the presentation of unpackaged food and the perceived knowledge and personal attention of vendors [34,35,68,69]. They were described as places where people felt less judged by appearances compared to grocery, serving as social equalisers [68,70], and to provide stable gathering points where people connected to their culture and traditions and found a sense of familiarity in the face of rapid societal shifts, encouraging social interactions and trust among diverse groups beyond family ties [68]. They were reported to be particularly important for women, lower-income earners, and the elderly [54]. | Papua New Guinea [65,66,67], Port Moresby [67], Barbados [69], Kiribati [55], Samoa [55], Solomon Islands [30,55,64,71], Tonga [55], Vanuatu [55], Pacific region [54], Belize [72], Kingston (Jamaica) [33,34], Cuba [60], Fiji [30,41], Haiti [26,70], Singapore [68], Turks and Caicos [45]. |

| Hospitality (Buy) | Referred by the evidence as ‘hotel’, ‘restaurant’, ‘kava bar’(only in evidence from the Pacific region to refer to bars specialised in serving drinks made of kava, a native plant), ‘hawker centre’ (term used in evidence from Singapore to refer to open-air food complexes with multiple vendors selling local prepared foods), ‘food court’ (found in larger shopping malls, an air-conditioned version of hawker centres), ‘takeaway’, ‘coffee shop stall’, and ‘corporate fast-food chain’. They were reported to offer very diverse food options and environments, with quick, affordable meals and extended menus (except for kava bars) [31,33,41,54,64,73,74]. Convenience and affordability were the main reasons reported for choosing this type of food source. The rise of Western fast-food chains was reported to raise health concerns due to associations with obesity and chronic diseases [74]. Younger individuals, particularly students, were reported to be the main population group affected by fast-food chains [13], as they frequented these places for socialising and studying, seeking a sense of belonging and identity within peer groups [73]. Instead, the elderly found their socialising spaces in hawker centres [73,74,75]. In Fiji, kava bars and street stalls were described as particularly relevant for urban dwellers to purchase cooked seafood and finfish [13,41]. | Dominican Republic [31], Caribbean region [38], Samoa [55], Pacific region [54], Kingston (Jamaica) [33], Fiji [13,41], Singapore [73,74,75], Solomon Islands [64], Saint Vincent and the Grenadines [13], Trinidad [46]. |

| Home-garden (Grow) | Home garden included the terms ‘urban garden’, ‘village garden’, ‘backyard garden’, ‘kitchen garden’, ‘domestic garden’, and ‘sup-sup garden’ (term used in evidence from Solomon Islands, which refers to organic backyard gardening). They are typically located adjacent to residences or nearby areas. These gardens varied in size but were often small, included recycled containers for cultivation, and followed organic agricultural practices [60,76,77,78]. Growers often lacked formal training [79], and primarily cultivated crops for household consumption [28,36,78,80,81], exchange, and gifting [82,83], with limited commercial sales [17,19,30,48,79,84,85,86,87]. The main foods cultivated included vegetables, fruits, herbs and crops easily adaptable to urban spaces, alongside occasional livestock (mainly chickens). Generally reported as enhancing food security, nutrition, and household economies by providing fresh produce, supplementing diets, and generating income, while also promoting social well-being through community ties, empowerment, and cultural preservation. Often described as a food source that offers resilience against economic downturns, environmental challenges, and stress, particularly evident during crises like COVID-19 (see Supplementary Materials for context-specific insights). | Pacific region [23,76,86], Marshall Islands [85,88], SIDS regions [81], Vanuatu [16,19,56,89], Fiji [30,56,61,82,83], Samoa [56], Solomon Islands [30,36,39,56], Tonga [56,82], Tuvalu [56], Trinidad and Tobago [79,90], Jamaica [84,91], Bahamas [92], Grenada [93], British Virgin Islands [94], Timor-Leste [58,80], Kingston (Jamaica) [33,95], Cuba [60,78], Antigua and Barbuda [48,87], Belize [28], Haiti [26], Puerto Rico [96], Kiribati [82], Nauru [82], Papua New Guinea [82], Turks and Caicos [45]. |

| Family farm (Grow) | Described as managed and operated by a family, predominantly relying on family labour. Compared to home gardens, these farms typically involved larger-scale production, a wider variety of crops, and the inclusion of diverse livestock and cash crops. They were described as using mixed cropping techniques and minimal inputs [20,97,98,99], aiming for self-sufficiency, sale and gifting, supporting both local food supply [25,100,101,102,103], and cultural obligations [43,104]. The production from family farming was described as ensuring food access to families during periods of supply shortage due to the COVID-19 pandemic [42,52,72,90,102,105,106], providing resilience against external shocks, whether economic (price spikes, global recession) or natural (cyclones, floods, droughts, pests, and diseases) [17,103,104]. | Caribbean region [25,53,69,97,104], Pacific region [86,103,107,108], SIDS region [100], Marshall Islands [109], Cook Islands [110,111], Solomon Islands [71,111,112,113,114], Tuvalu [43,115], Kiribati [115], Fiji [20,27,41,111,112,116], Timor-Leste [58,117], Samoa [42,101,111,116], Nauru [118], Comoros [99], Tonga [111,113], Vanuatu [17,18,111,112,119], Papua New Guinea [111,120], Saint Kitts and Nevis [105], Saint Lucia [106], Guyana [121], Belize [72], Barbados [52], Dominica [102], Guinea-Bissau [122], Seychelles [77], Cuba [98,123]. |

| Community farm (Grow) | Described as located on idle public lands in various urban and rural settings [123,124,125], and organised by charities, non-profit associations, cooperatives, social enterprises, or groups of neighbours. Cultivation practices were reported to occur in raised beds or existing soil with minimal external inputs. Community farms also grew a variety of crops, including starchy foods, vegetables, and fruits, alongside herbs and medicinal plants, with occasional integration of poultry and pigs. Produce was reported to be typically divided among farmers [79,124], and sold at local markets or through food box schemes to support garden operations contributing to local food supply [60,79,125,126,127], and to the tourism sector [127]. Described as educational and cultural hubs for the community [63,123,124,128], serving a socialising role [29,123,124]. | Caribbean region [25], Nauru [82,118], Havana (Cuba) [129], Cuba [60,78,123,125,127], Singapore [29,63,126], Trinidad and Tobago [79], Puerto Rico [124], Papua New Guinea [82], Fiji [82], Tonga [82], Kiribati [82], Jamaica [128]. |

| Gift (Share) | Reported as the exchange of food items within various social contexts, including schools, families, neighbourhoods, and communities [13,28,33,50,58,110]. Described as traditions of communal support, such as sharing farming produce and fish catches, especially during times of need [18,30,54,58,106,130,131]. This practice was sometimes reported to be facilitated through community initiatives promoting knowledge sharing and solidarity [29,63,132]. Food gifts to those in need were driven by moral responsibility and reciprocity [44,80,131]. Overall, food gifting reinforced social bonds and mutual assistance, serving as a form of social capital within communities. | Samoa [111,133], Pacific region [54,130,134], Cook Islands [111], Fiji [27,30,111], Papua New Guinea [111], Solomon Islands [30,111,135], Tonga [50,111,136,137], Vanuatu [18,111,138], Saint Lucia [106], Timor-Leste [58,80], Kingston (Jamaica) [33], Singapore [29,63,132], Kiribati [139], Tuvalu [140], Belize [28], Haiti [26], Cuba [125], Dominican Republic [44]. |

| Barter (Share) | Described as the trade of food for goods or services without money [30,39,88,109,131]. It occurred between communities and saw a resurgence during the COVID-19 pandemic, facilitated by social media platforms [30,141,142,143]. This strategy proved valuable during times of uncertainty, allowing people to meet their basic needs [44,138,141]. | Solomon Islands [30,39], Fiji [30,141], Samoa [142,143], Puerto Rico [131], Vanuatu [138], Dominican Republic [44], Jamaica [128]. |

| Remit (Share) | Typically involved the exchange of food or cash between different locations, such as from a main island to outer islands within the same country, between different countries, or across diverse community settings like coastal and highland areas. This exchange often occurred within familial relationships, distinguishing it from barter, which may have lacked this personal connection. Unlike bartering, food remittances held emotional significance, as foods were believed to have unique flavours and carried strong sentimental value. | New Caledonia [88], Marshall Islands [109], Jamaica [91], Kingston (Jamaica) [33,95], Tuvalu [43], Fiji [61], Vanuatu [16,18]. |

| Feast (Share) | Described as a common tradition in ceremonies and celebrations that was important for communities [61,88,144,145,146,147]. Sundays were reported as special “feasting days” when food was shared in a structured way, reflecting social status [61,147]. According to the evidence, feasting went beyond immediate family, lasting several days and needing careful planning [145]. During various community events, like church gatherings and holidays, feasting involved everyone contributing dishes, creating a sense of unity and responsibility. It was reported to involve large quantities of diverse foods. | Cook Islands [88], Papua New Guinea [144], Fiji [61,147], Vanuatu [145], Guam [146]. |

| School meals (State) | Described as covering various programs, including universal schemes providing free daily meals to students in public or semi-public schools. Meals were reported to face challenges in meeting national guidelines due to funding limitations [148]. Some reported programmes consisted of preparing cooked meals in school canteens, while others prepared the lunches centrally and distributed them to schools [28,59]. Some programs were reported to integrate school gardens to enhance food diversity and freshness [41,149]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, adaptations such as take-home rations and food vouchers were reported to be introduced [150]. | Caribbean region [53], Dominica [150], Guyana [150,151], Jamaica [59,150], Saint Lucia [150], Trinidad and Tobago [150,152], Aruba [150], Sint Maarten [150], Cuba [148], Dominican Republic [148], Haiti [148], Fiji [41], Belize [28,149,150]. |

| Baskets (State) | Described as provided by the government and typically containing locally grown foods as well as rice and other staples [117]. These baskets were reported to be distributed through beneficiary cards or ration cards, offering discounts or fixed-price options [60,153]. However, consistent support was a challenge for some programmes, with only small monthly food baskets available to families in need [28,37]. | Timor-Leste [117], Vanuatu [56], Belize [28,153], Cuba [60,148], Dominican Republic [148], Haiti [148], French Polynesia [37]. |

| Assistance (State) | Described as provided by the governments in response to specific events or situations. For example, it was reported that to address the limited market access for farmers, some governments established connections between farmers and schools, allowing farmer groups to supply the feeding programs [117,148,154,155]. These programmes were reported as having introduced new and improved farming opportunities and technologies for the local market [155]. | Palau [156], Marshall Islands [156], Samoa [156], Solomon Islands [154], Cuba [148], Dominican Republic [148], Haiti [148], Trinidad and Tobago [155], Saint Kitts and Nevis [155], Guyana [155], Saint Lucia [155], Belize [28], Timor-Leste [117]. |

| Forage (Wild) | According to evidence, it involved the gathering of wild foods from natural environments such as forests, bushlands, and uncultivated farmlands. Some collectors were reported to specialise in certain foods while others gathered a variety of them [128]. Consumption of foraged foods was reported to vary with the seasons, with methods like drying tubers for storage during the wet season [157]. Foraging was reported to include diverse food types like tree crops, wild plants, fruits, nuts, staples, and root vegetables, ensuring a varied diet. | Caribbean region [158], SIDS region [159], Solomon Islands [30,36,39,114], Papua New Guinea [126], Fiji [27,30,41,83], Timor-Leste [80,157], Vanuatu [18,145], Jamaica [128]. |

| Hunt (Wild) | Reported as typically involving individuals or small groups using trained dogs, spears, or bows and arrows [27,39]. According to the evidence, the most targeted animal was the wild pig. Other reported hunted foods included mammals, rodents, reptiles, birds, insects, and worms, as well as animal products such as honey, eggs, and birds’ nests. | Caribbean region [158], SIDS region [159], Solomon Islands [36,39,114], Timor-Leste [58,157], Papua New Guinea [126], Fiji [27], Vanuatu [145], Jamaica [128]. |

| Fish (Wild) | Described as including open ocean, mangroves, mudflats, coral reefs, and rivers. Coastal and inland communities were reported to rely on these diverse ecosystems for animal protein. Artisanal methods like manual collection, spearfishing and hook and line fishing, or the use of small boats were common [54,134]. Gender dynamics played a significant role in fishing practices, with fishing activities often segregated based on location or habitat [20,39,160,161]. It was reported that fishing ability could symbolise social status, with individuals gaining prestige by catching more fish and enhancing their reputation within the community by sharing greater amounts of the catch [130]. | Caribbean region [158,162,163], SIDS region [81], Pacific region [54,86,103,107,130,134,164], Cook Islands [110], Fiji [20,30,41,112,160,165], Vanuatu [112], Tonga [137,165], Samoa [42,165], Tuvalu [43,165], Belize [72], Dominica [102], British Virgin Islands [94], Timor-Leste [58], Papua New Guinea [126], French Polynesia [37], Kiribati [161], Solomon Islands [30,36,39,112,165]. |

| Rural-Urban Food Exchanges | Implications |

|---|---|

| We saw from the evidence that food transfers of wild, grown, or bought foods occurred between relatives living in rural areas and those in urban centres. For example, in Fiji, residents of remote coastal areas in outer islands often relied on family members in urban centres to obtain fresh produce unavailable locally, facilitated by weekly boat shipments [61]. Similarly, local foods that arrived in Funafuti (the capital of Tuvalu) from the outer islands were shared extensively between neighbours and relatives [43]. In the Republic of Marshall Islands, locally grown food crops were traditionally not sold but shared or exchanged between communities [109]. | These connections between rural-urban food sources have some implications. First, that wild, grown, or bought food by an individual or family is not always consumed by them; instead, food can be sent to relatives elsewhere or shared extensively with others. Second, they show that fresh produce also flows from urban to rural settings. While rural areas may be perceived as the primary source of food production, these connections highlight how urban settings can also provide fresh produce to remote rural areas. |

| In Tuvalu, there were exchanges of local atoll foods such as fresh and dried fish, pulaka (a local root rich in carbohydrates), bananas, coconut, and breadfruit for imported items such as ultra-processed foods and non-food items such as floor coverings [43]. Coastal-mountain food transfers, as seen in New Caledonia and Vanuatu, involved the exchange of wild or grown foods among family members, contributing to dietary diversity [16,88]. In Jamaica, monthly food transfers from rural to urban areas included home-grown fruits, vegetables, provisions, and meats, with urban dwellers also benefiting from occasional food and cash remittances from relatives overseas [33,91,95]. | These connections show that rural-urban food transfers can involve the exchange of foods from different food groups and origins than the initially sourced (e.g., fresh fish for soft drinks, and local food crops for imported food items), or even for non-food items such as home decorations. The connections also indicate that an individual’s food consumption is not necessarily reliant on the food sources available at their place of residence. Instead, external factors such as remittances influence food access and availability. This suggests that migration patterns and remittance practices can shape food consumption and dietary patterns within communities in unexpected ways. |

| Informal grocery interconnections | Implications |

| We found from the evidence that food purchased from informal grocery outlets (including street-food vendors, corner shops, food trucks, colmados, small shops, roadside stalls, or itinerant stalls) was interconnected with many other food sources. For example, fisherwomen in rural areas of many Pacific islands used part of their catches for sale. Although much of the fish catch (mainly invertebrates such as bivalve molluscs, crustaceans, sea cucumber, and algae) was consumed at home or shared with relatives, a small portion was sold, mainly through informal roadside markets [54]. These women also added value to their catches, preparing traditional dishes like puddings covered in coconut cream for sale to roadside buyers [20,54,160]. Since little cash was involved, these practices were seen by policymakers and donors as less important food sources than commercial fisheries [54]. | This connection between fishing and informal grocery demonstrates that fish caught is not only sold in formal markets; instead, informal roadside markets are also important in local food distribution and serve as a platform for the multifaceted roles of women in local food economies. |

| Similarly, an example from Jamaica showed that women who were street-food vendors opted to raise chickens at home instead of growing vegetables, after recognising a market demand for chicken sales [84]. | This connection between home gardens and informal grocery sources, such as street vendors, shows that home gardens not just supply vegetables for personal consumption; instead, they show that individuals adapt their home food production based on informal market opportunities. |

| An example from Samoa showed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a rise in families selling their surplus fruits and vegetables in roadside stalls near their homes (although with a decrease during lockdowns), which provided nearby communities with access to fresh produce [42]. | This connection between family farming and informal grocery shows that during crises, food security is not solely ensured by external food aid; instead, it shows a contribution of family farming to the resilience of local food systems in remote areas during crisis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brugulat-Panés, A.; Guell, C.; Unwin, N.; Martin-Pintado, C.; Iese, V.; Augustus, E.; Foley, L. Examining Food Sources and Their Interconnections over Time in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142353

Brugulat-Panés A, Guell C, Unwin N, Martin-Pintado C, Iese V, Augustus E, Foley L. Examining Food Sources and Their Interconnections over Time in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2025; 17(14):2353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142353

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrugulat-Panés, Anna, Cornelia Guell, Nigel Unwin, Clara Martin-Pintado, Viliamu Iese, Eden Augustus, and Louise Foley. 2025. "Examining Food Sources and Their Interconnections over Time in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Scoping Review" Nutrients 17, no. 14: 2353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142353

APA StyleBrugulat-Panés, A., Guell, C., Unwin, N., Martin-Pintado, C., Iese, V., Augustus, E., & Foley, L. (2025). Examining Food Sources and Their Interconnections over Time in Small Island Developing States: A Systematic Scoping Review. Nutrients, 17(14), 2353. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142353