Psychological Well-Being and Dysfunctional Eating Styles as Key Moderators of Sustainable Eating Behaviors: Mind the Gap Between Intention and Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aims and Hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Measures

- Predictors of Intention. To assess predictors of intention to engage in more sustainable eating behaviors as proposed by TPB (attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control) and TBC (attitude plus, affect, felt obligation, and habits) models, a 31-item ad hoc questionnaire on a 7-point Likert scale was used. The questionnaire was adapted from a previous study [12].

- Sustainable and Healthy Dietary Behaviors (SHDB) [40]. A 33-item questionnaire on a 6-point Likert scale consisting of five dimensions was used to assess sustainable and healthy eating behaviors. The five dimensions included food choices (e.g., choosing the right amount of food, choosing locally produced and organic food, avoiding processed food), storing (e.g., checking the expiration dates of food), cooking (e.g., minimizing the use of disposable materials, making a menu so that groceries will not be discarded), consumption (e.g., avoiding the use of plastic cutlery), and disposal (e.g., recycling garbage). Scores range between 1 and 5, with higher scores indicating greater sustainable eating behaviors. So far, the questionnaire has been validated only in the Japanese population, showing adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) [40]. The authors emphasized that providing information on healthy eating and sustainability, highlighting the associated benefits, is needed to promote behaviors such as choosing healthy foods and sustainable cooking practices. The questionnaire was translated into Italian using the back-translation method. This method involves an initial translation of the items from the original language into Italian by at least two researchers who must agree on the final version. This version is then reviewed by a bilingual individual who, through a re-translation into the original language, confirms the comparability between the two versions [41].

- Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21) [42]; Italian version by Bottesi et al. 2015 [43]. To assess distress levels, a 21-item questionnaire on a 4-point Likert scale consisting of three dimensions (depression, anxiety, and stress) was used. Normal level ranges are 0–9 for depression, 0–7 for anxiety and 0–14 for stress; mild level ranges are 10–13 for depression, 8–9 for anxiety and 15–18 for stress; moderate level ranges are 14–20 for depression, 10–14 for anxiety and 19–25 for stress; severe level ranges are 21–27 for depression, 15–19 for anxiety and 26–33 for stress; extremely severe level ranges are 28 or more for depression, 20 or more for anxiety and 34 or more for stress. The Italian version of the DASS-21 showed good internal consistency (α = 0.90) and test–retest reliability over 2 weeks (r = 0.74) [43].

- Psychological Well-Being Scales, short form (PWBS) [44]; Italian version by Ruini et al. 2003 [45]. A 42-item questionnaire on a 6-point Likert scale consisting of six dimensions (autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance) was used to assess psychological well-being. Scores range between 7 and 42, with mid-range values indicating an optimal healthy range. The Italian version of the PWB showed good internal consistency and test–retest reliability for all six subscales, especially positive relations with others (r = 0.81), purpose in life (r = 0.81), and self-acceptance (r = 0.82) [45].

- Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) [46]; Italian version by Dakanalis et al. 2013 [47]. A 33-item questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale consisting of three dimensions (restrained, emotional, and external eating) was used to assess dysfunctional eating styles. Scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more dysfunctional eating styles. The Italian version of the DEBQ showed a high internal consistency (α = 0.96 for emotional eating, α = 0.93 for external eating, and α = 0.92 for restrained eating) and test–retest reliability over 4 weeks (r = 0.93 for emotional eating, r = 0.92 for external eating, and r = 0.94 for restrained eating) [47].

3.3. Data Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Bi-Directional Associations Between Sustainable Eating Behaviors and Intention, Psychological Well-Being, Dysfunctional Eating Styles, and Distress

4.3. Comparison of TPB and TBC Predictors of the Intention to Engage in Healthy and Sustainable Eating Behaviors

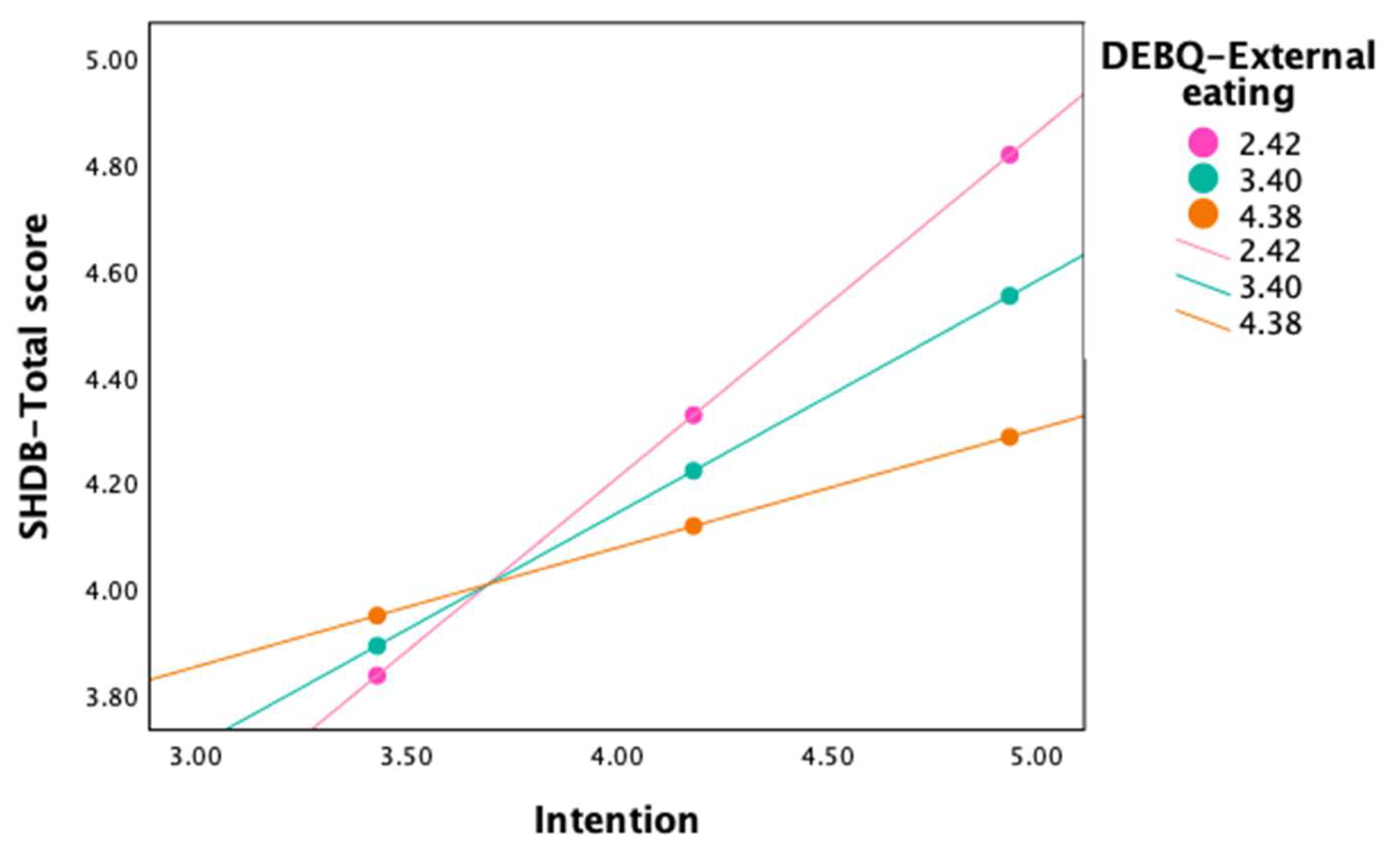

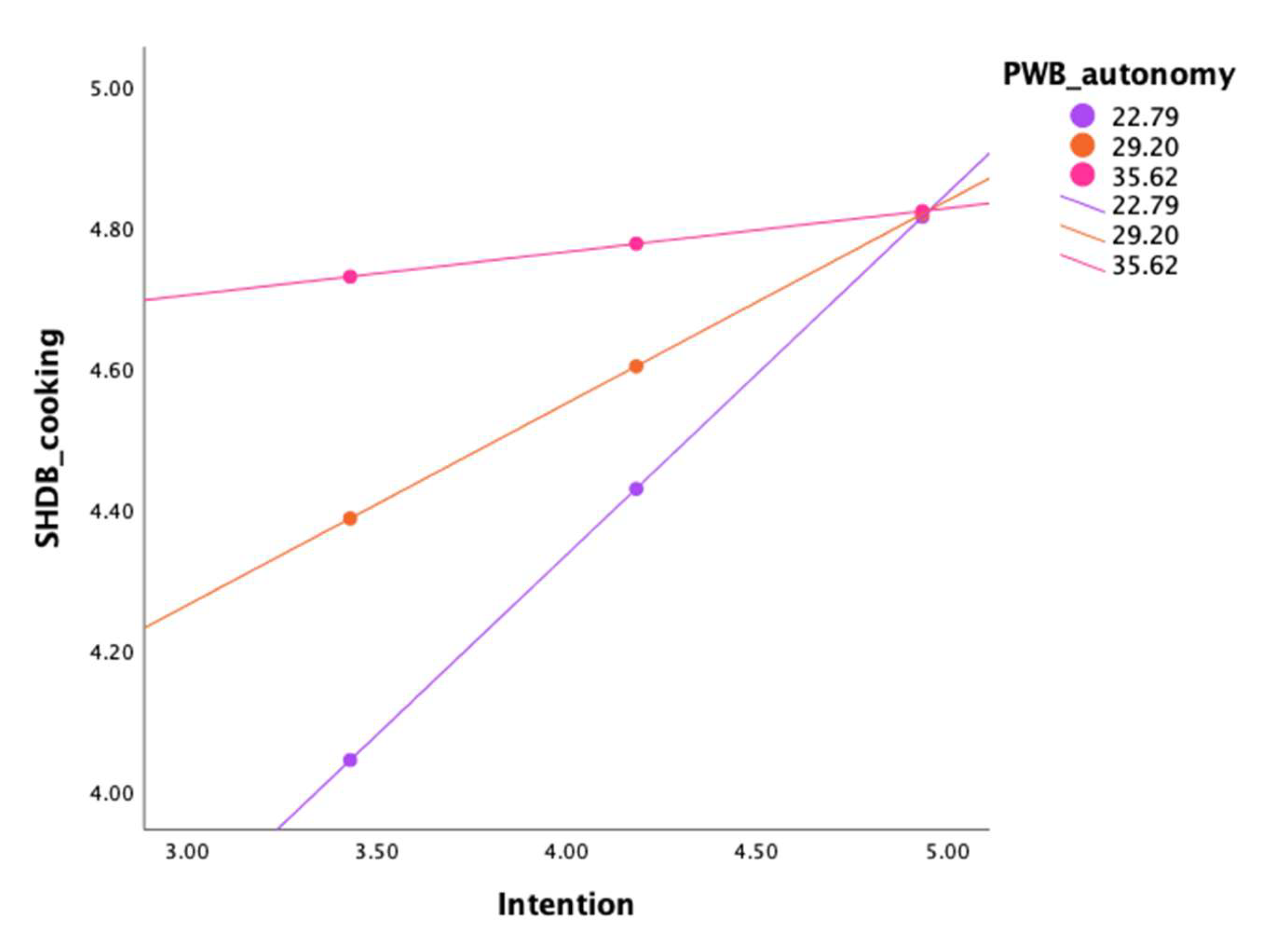

4.4. Psychological Moderators in the Relation Between Intention and Behavior

5. Discussion

Limitations, Future Directions, and Clinical Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lindgren, E.; Harris, F.; Dangour, A.D.; Gasparatos, A.; Hiramatsu, M.; Javadi, F.; Loken, B.; Murakami, T.; Scheelbeek, P.; Haines, A. Sustainable Food Systems-a Health Perspective. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The Global Obesity Pandemic: Shaped by Global Drivers and Local Environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The Nutrition Transition to a Stage of High Obesity and Non-communicable Disease Prevalence Dominated by Ultra-Processed Foods Is Not Inevitable. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2022, 23, e13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremmel, M.; Gerdtham, U.-G.; Nilsson, P.M.; Saha, S. Economic Burden of Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable Food Consumption among Young Adults in Belgium: Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Role of Confidence and Values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Verbeke, W.; Mondelaers, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Personal Determinants of Organic Food Consumption: A Review. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1140–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjar, S.; Graaf, C.D.; Kooijman, V.M.; de Wijk, R.A.; Nys, A.; ter Horst, G.J.; Jager, G. The Role of Emotions in Food Choice and Liking. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Dato, E.; Gostoli, S.; Tomba, E. Psychological Theoretical Frameworks of Healthy and Sustainable Food Choices: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Lacroix, K.; Asgarizadeh, Z.; Anderson, E.A.; Milne-Ives, M.; Sugrue, P. Climate Change, Food Choices, and the Theory of Behavioral Choice. Res. Sq. 2022; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Lacroix, K.; Asgarizadeh, Z.; Ashford Anderson, E.; Milne-Ives, M.; Sugrue, P. Applying the Theory of Behavioral Choice to Plant-Based Dietary Intentions. Appetite 2024, 197, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. Empowering Interventions to Promote Sustainable Lifestyles: Testing the Habit Discontinuity Hypothesis in a Field Experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Godin, G.; Sheeran, P.; Germain, M. Some Feelings Are More Important: Cognitive Attitudes, Affective Attitudes, Anticipated Affect, and Blood Donation. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2013, 32, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkiniemi, J.-P.; Vainio, A. Moral Intensity and Climate-Friendly Food Choices. Appetite 2013, 66, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horovitz, O. Nutritional Psychology: Review the Interplay Between Nutrition and Mental Health. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, E.-T.; Fonseca, S. The Effect of Food on Mental Health. Rev. Int. Educ. Saúde Ambiente 2020, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Conner, M.; Clancy, F.; Moss, R.; Wilding, S.; Bristow, M.; O’Connor, D.B. Stress and Eating Behaviours in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2022, 16, 280–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.H.; Kristal, A.R.; Neumark-Sztainaer, D.; Rock, C.L.; Neuhouser, M.L. Psychological Distress Is Associated with Unhealthful Dietary Practices. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Oberänder, N.; Weimann, A. Four Main Barriers to Weight Loss Maintenance? A Quantitative Analysis of Difficulties Experienced by Obese Patients after Successful Weight Reduction. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheloni, G.; Cocchi, C.; Sinigaglia, G.; Coppi, F.; Zanini, G.; Moscucci, F.; Sciomer, S.; Nasi, M.; Desideri, G.; Gallina, S.; et al. Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet: A Nutritional and Environmental Imperative. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, O.; Keshteli, A.H.; Afshar, H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Adibi, P. Adherence to Mediterranean Dietary Pattern Is Inversely Associated with Depression, Anxiety and Psychological Distress. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanatta, F.; Mari, S.; Adorni, R.; Labra, M.; Matacena, R.; Zenga, M.; D’Addario, M. The Role of Selected Psychological Factors in Healthy-Sustainable Food Consumption Behaviors during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2022, 11, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushlev, K.; Drummond, D.M.; Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being and Health Behaviors in 2.5 Million Americans. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020, 12, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Cohen, S. Does Positive Affect Influence Health? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 925–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, J.K.; Soo, J.; Zevon, E.S.; Chen, Y.; Kim, E.S.; Kubzansky, L.D. Longitudinal Associations between Psychological Well-Being and the Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, A.L.; Branco, T.L.; Martins, S.C.; Minderico, C.S.; Silva, M.N.; Vieira, P.N.; Barata, J.T.; Serpa, S.O.; Sardinha, L.B.; Teixeira, P.J. Change in Body Image and Psychological Well-Being during Behavioral Obesity Treatment: Associations with Weight Loss and Maintenance. Body Image 2010, 7, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, M. Quality of Life and Psychological Well-Being in Obesity Management: Improving the Odds of Success by Managing Distress. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2016, 70, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Gostoli, S.; Benasi, G.; Patierno, C.; Petroni, M.L.; Nuccitelli, C.; Marchesini, G.; Fava, G.A.; Rafanelli, C. The Role of Psychological Well-Being in Weight Loss: New Insights from a Comprehensive Lifestyle Intervention. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2022, 22, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral Verdugo, V. The Positive Psychology of Sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2012, 14, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilici, S.; Ayhan, B.; Karabudak, E.; Koksal, E. Factors Affecting Emotional Eating and Eating Palatable Food in Adults. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2020, 14, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt-Núñez, A.; Torres-Castillo, N.; Martínez-López, E.; De Loera-Rodríguez, C.O.; Durán-Barajas, E.; Márquez-Sandoval, F.; Bernal-Orozco, M.F.; Garaulet, M.; Vizmanos, B. Emotional Eating and Dietary Patterns: Reflecting Food Choices in People with and without Abdominal Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anschutz, D.J.; Van Strien, T.; Van De Ven, M.O.M.; Engels, R.C.M.E. Eating Styles and Energy Intake in Young Women. Appetite 2009, 53, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijs, I.M.T.; Muris, P.; Euser, A.S.; Franken, I.H.A. Differences in Attention to Food and Food Intake between Overweight/Obese and Normal-Weight Females under Conditions of Hunger and Satiety. Appetite 2010, 54, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleobury, L.; Tapper, K. Reasons for Eating “unhealthy” Snacks in Overweight and Obese Males and Females. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2014, 27, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, D.; Guidetti, M.; Capasso, M.; Cavazza, N. Finally, the Chance to Eat Healthily: Longitudinal Study about Food Consumption during and after the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gortat, M.; Samardakiewicz, M.; Perzyński, A. Orthorexia Nervosa—A Distorted Approach to Healthy Eating. Psychiatr. Pol. 2021, 55, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, Y.; Nagao-Sato, S.; Yoshii, E.; Akamatsu, R. Integrated Consumers’ Sustainable and Healthy Dietary Behavior Patterns: Associations between Demographics, Psychological Factors, and Meal Preparation Habits among Japanese Adults. Appetite 2023, 180, 106353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, O.; Law, K. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments: Problems and Solutions; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The Structure of Negative Emotional States: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottesi, G.; Ghisi, M.; Altoè, G.; Conforti, E.; Melli, G.; Sica, C. The Italian Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties on Community and Clinical Samples. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 60, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruini, C.; Ottolini, F.; Rafanelli, C.; Ryff, C.; Fava, G.A. La validazione italiana delle Psychological Well-being Scales (PWB). Riv. Psichiatr. 2003, 38, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.; Bergers, G.P.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for Assessment of Restrained, Emotional, and External Eating Behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Zanetti, M.A.; Clerici, M.; Madeddu, F.; Riva, G.; Caccialanza, R. Italian Version of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire. Psychometric Proprieties and Measurement Invariance across Sex, BMI-Status and Age. Appetite 2013, 71, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2020; ISBN 978-93-5150-082-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: Third Edition: A Regression-Based Approach. Available online: https://www.guilford.com/books/Introduction-to-Mediation-Moderation-and-Conditional-Process-Analysis/Andrew-Hayes/9781462549030 (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal-Directed Behaviours: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Belanche, D.; Casaló Ariño, L.; Flavian, C. The Role of Anticipated Emotions in Purchase Intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, H. Advantages of Anticipated Emotions over Anticipatory Emotions and Cognitions in Health Decisions: A Meta-Analysis. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitraranjan, C.; Botenne, C. Association between Anticipated Affect and Behavioral Intention: A Meta-Analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 1929–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.D.; Gilbert, D.T. Affective Forecasting. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 35, 345–411. [Google Scholar]

- Toukabri, M. Determinants of Healthy Eating Intentions among Young Adults. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabia-Sánchez, F.J.; Boluda, I.K.; Vila-Lopez, N.; Sarabia-Andreu, F. Belonging and Beliefs: How Social Influences Drive the Intention to Purchase Foods with Health Claims. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvola, A.; Vassallo, M.; Dean, M.; Lampila, P.; Saba, A.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Shepherd, R. Predicting Intentions to Purchase Organic Food: The Role of Affective and Moral Attitudes in the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Appetite 2008, 50, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An Exploration of the Functions of Anticipated Pride and Guilt in pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, R.; Larsen, S. The Relative Importance of Social and Personal Norms in Explaining Intentions to Choose Eco-Friendly Travel Options. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Ahmad, M.; Ho, Y.-H.; Omar, N.A.; Lin, C.-Y. Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Sustainable Food Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Herman, C.P.; Verheijden, M.W. Eating Style, Overeating, and Overweight in a Representative Dutch Sample. Does External Eating Play a Role? Appetite 2009, 52, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfhag, K.; Morey, L.C. Personality Traits and Eating Behavior in the Obese: Poor Self-Control in Emotional and External Eating but Personality Assets in Restrained Eating. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, R.; Nederkoorn, C.; Stankiewicz, K.; Alberts, H.; Geschwind, N.; Martijn, C.; Jansen, A. The Influence of Trait and Induced State Impulsivity on Food Intake in Normal-Weight Healthy Women. Appetite 2007, 49, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, T.; Ward, A. The Self-Control of Eating. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2025, 76, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R. Self-Regulation and Self-Control: Selected Works of Roy F. Baumeister; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-351-70774-9. [Google Scholar]

- Paschke, L.M.; Dörfel, D.; Steimke, R.; Trempler, I.; Magrabi, A.; Ludwig, V.U.; Schubert, T.; Stelzel, C.; Walter, H. Individual Differences in Self-Reported Self-Control Predict Successful Emotion Regulation. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamayek, C.; Paternoster, R.; Loughran, T.A. Self-Control as Self-Regulation: A Return to Control Theory. Deviant Behav. 2017, 38, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Yielding to Temptation: Self-Control Failure, Impulsive Purchasing, and Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 28, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Dadzie, C.A.; Chaudhuri, H.R.; Tanner, T. Self-Control and Sustainability Consumption: Findings from a Cross Cultural Study. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2019, 31, 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Olmedo, A.M.; Valor, C.; Carrero, I. Mindfulness in Education for Sustainable Development to Nurture Socioemotional Competencies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1527–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.; Singer, B. Psychological Weil-Being: Meaning, Measurement, and Implications for Psychotherapy Research. Psychother. Psychosom. 1996, 65, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B. Personality and Environmental Concern. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-08589-000 (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Mireles-Acosta, J.; Tapia-Fonllem, C.; Fraijo-Sing, B. Happiness as Correlate of Sustainable Behavior: A Study of Pro-Ecological, Frugal, Equitable and Altruistic Actions That Promote Subjective Wellbeing. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2011, 18, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.W.; Kasser, T. Are Psychological and Ecological Well-Being Compatible? The Role of Values, Mindfulness, and Lifestyle. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 74, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. Orthorexia Nervosa: Healthy Eating or Eating Disorder? Master’s Thesis, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koven, N.S.; Abry, A.W. The Clinical Basis of Orthorexia Nervosa: Emerging Perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Kapoor, N.; Jacob, J. Orthorexia Nervosa. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2020, 70, 1282–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Tecuta, L.; Casu, G.; Tomba, E. Validation of the Italian Version of the Eating-Related Eco-Concern Questionnaire: Insights into Its Relationship with Orthorexia Nervosa. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1441561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 29.49 (9.30) |

| N (%) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 153 (68.6%) |

| Male | 69 (30.9%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.4%) |

| Education | |

| No qualification | 1 (0.4%) |

| Middle school | 3 (1.3%) |

| High school | 59 (26.5%) |

| Bachelor degree | 44 (19.7%) |

| Master degree | 102 (45.7%) |

| Other | 14 (6.3%) |

| Occupation | |

| Employee | 166 (74.4%) |

| Student/internee | 30 (13.4%) |

| Unemployed | 8 (3.6%) |

| Retired | 1 (0.4%) |

| Other | 18 (8.1%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 66 (29.6%) |

| In a relationship | 136 (60.9%) |

| Married | 16 (7.2%) |

| Separated/divorced | 5 (2.2%) |

| Nutrition | |

| Omnivorous | 182 (81.6%) |

| Lacto-vegetarian | 5 (2.2%) |

| Ovo-vegetarian | 1 (0.4%) |

| Lacto–ovo vegetarian | 9 (4.0%) |

| Vegan | 4 (1.8%) |

| Flexitarian | 15 (6.7%) |

| Pesco–lacto–ovo vegetarian | 7 (3.1%) |

| Variables | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Sustainable and Healthy Dietary Behaviors (SHDBs) | |

| Food choices | 3.68 (0.98) |

| Food preservation | 4.59 (1.2) |

| Cooking | 4.6 (0.95) |

| Food consumption | 5.3 (0.91) |

| Food disposal | 4.52 (0.88) |

| Total | 4.20 (0.75) |

| Depression and Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) | |

| Depression | 13.63 (10.69) |

| Anxiety | 10.88 (9.66) |

| Stress | 19.83 (10.33) |

| Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWBS) | |

| Autonomy | 29.20 (6.41) |

| Environmental mastery | 27.35 (4.71) |

| Personal growth | 33.70 (4.92) |

| Positive relations with others | 31.97 (5.62) |

| Purpose in life | 29.89 (5.70) |

| Self-acceptance | 28.74 (6.96) |

| Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) | |

| Restriction | 2.54 (1.05) |

| External eating | 3.40 (0.97) |

| Emotional eating | 2.42 (1.15) |

| F (df) | f2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (TPB) | 0.178 | - | 17.03 (3, 219) | - | - | 0.22 |

| Model 2 (TBC) | 0.453 | 0.281 | 28.52 (4, 215) | 28.52 | <0.01 | 0.83 |

| B | SE | β | t (p) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (TPB) | |||||

| Attitudes | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 2.11 (0.04) | [0.01, 0.25] |

| Subjective norms | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 3.70 (<0.01) | [0.06, 0.22] |

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 4.29 (<0.01) | [0.09, 0.25] |

| Model 2 (TBC) | |||||

| Attitudes | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 1.22 (0.22) | - |

| Social norms | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 2.13 (0.03) | [0.01, 0.13] |

| PBC | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 1.38 (0.17) | - |

| Attitude plus | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 1.14 (0.25) | - |

| Habits | 0.005 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.18 (0.86) | - |

| Felt obligation | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 4.06 (<0.01) | [0.08, 0.20] |

| Affect | 0.50 | 0.06 | 0.48 | 8.13 (<0.01) | [0.38, 0.62] |

| DEBQ-External Eating | Effect | SE | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.42 | 0.65 | 0.09 | 7.49 | <0.01 | [0.48, 0.82] |

| 3.40 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 7.25 | <0.01 | [0.31, 0.56] |

| 4.38 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 2.78 | <0.01 | [0.06, 0.38] |

| PWB-Autonomy | Effect | SE | t | p | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22.79 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 3.30 | <0.01 | [0.21, 0.82] |

| 29.20 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 2.73 | <0.01 | [0.08, 0.49] |

| 35.62 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.68 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lo Dato, E.; Gostoli, S.; Tomba, E. Psychological Well-Being and Dysfunctional Eating Styles as Key Moderators of Sustainable Eating Behaviors: Mind the Gap Between Intention and Action. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152391

Lo Dato E, Gostoli S, Tomba E. Psychological Well-Being and Dysfunctional Eating Styles as Key Moderators of Sustainable Eating Behaviors: Mind the Gap Between Intention and Action. Nutrients. 2025; 17(15):2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152391

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo Dato, Elena, Sara Gostoli, and Elena Tomba. 2025. "Psychological Well-Being and Dysfunctional Eating Styles as Key Moderators of Sustainable Eating Behaviors: Mind the Gap Between Intention and Action" Nutrients 17, no. 15: 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152391

APA StyleLo Dato, E., Gostoli, S., & Tomba, E. (2025). Psychological Well-Being and Dysfunctional Eating Styles as Key Moderators of Sustainable Eating Behaviors: Mind the Gap Between Intention and Action. Nutrients, 17(15), 2391. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17152391