Is Involvement in Food Tasks Associated with Psychosocial Health in Adolescents? The EHDLA Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Involvement in Household Food Tasks

2.3. Psychosocial Health

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

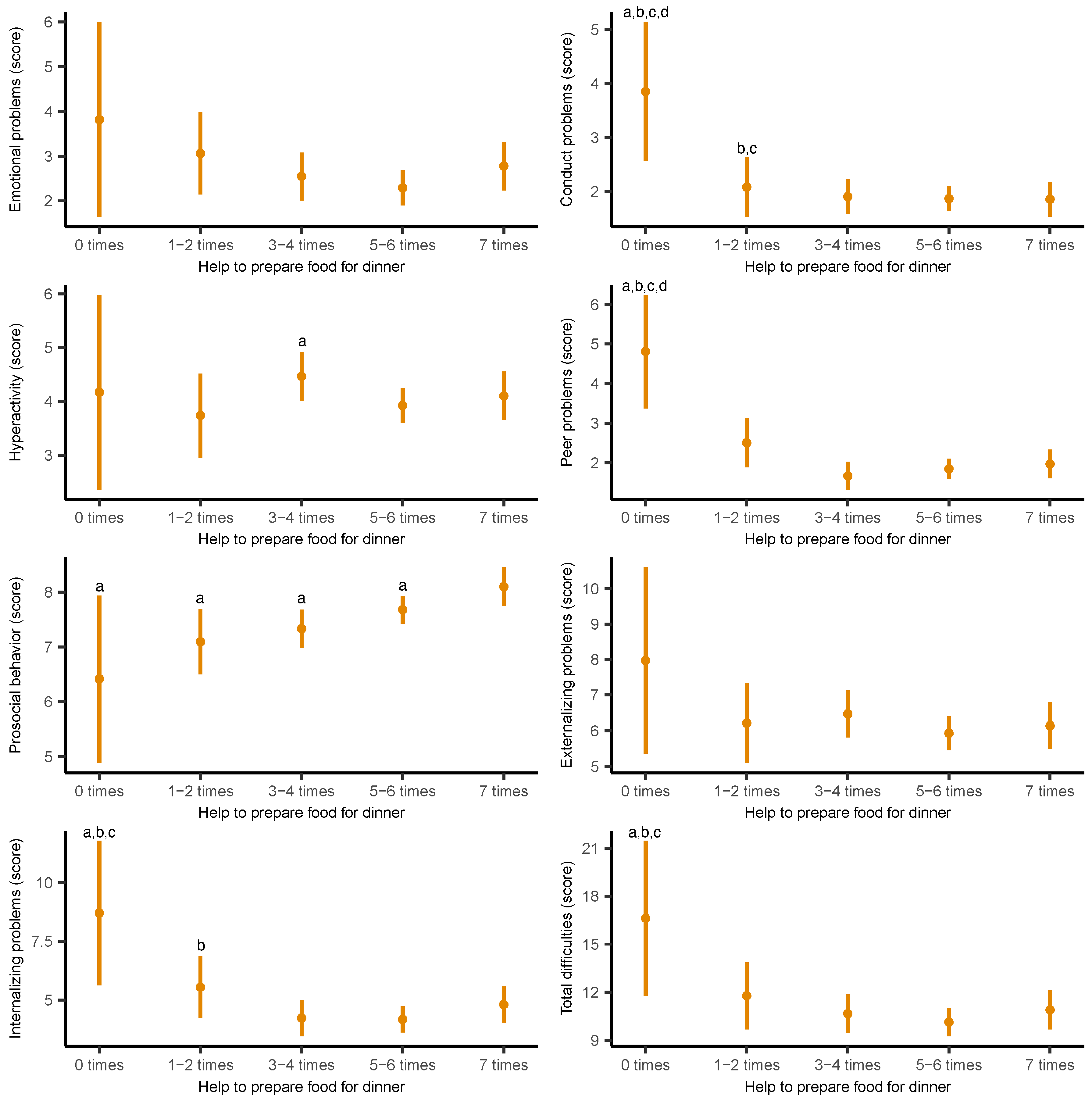

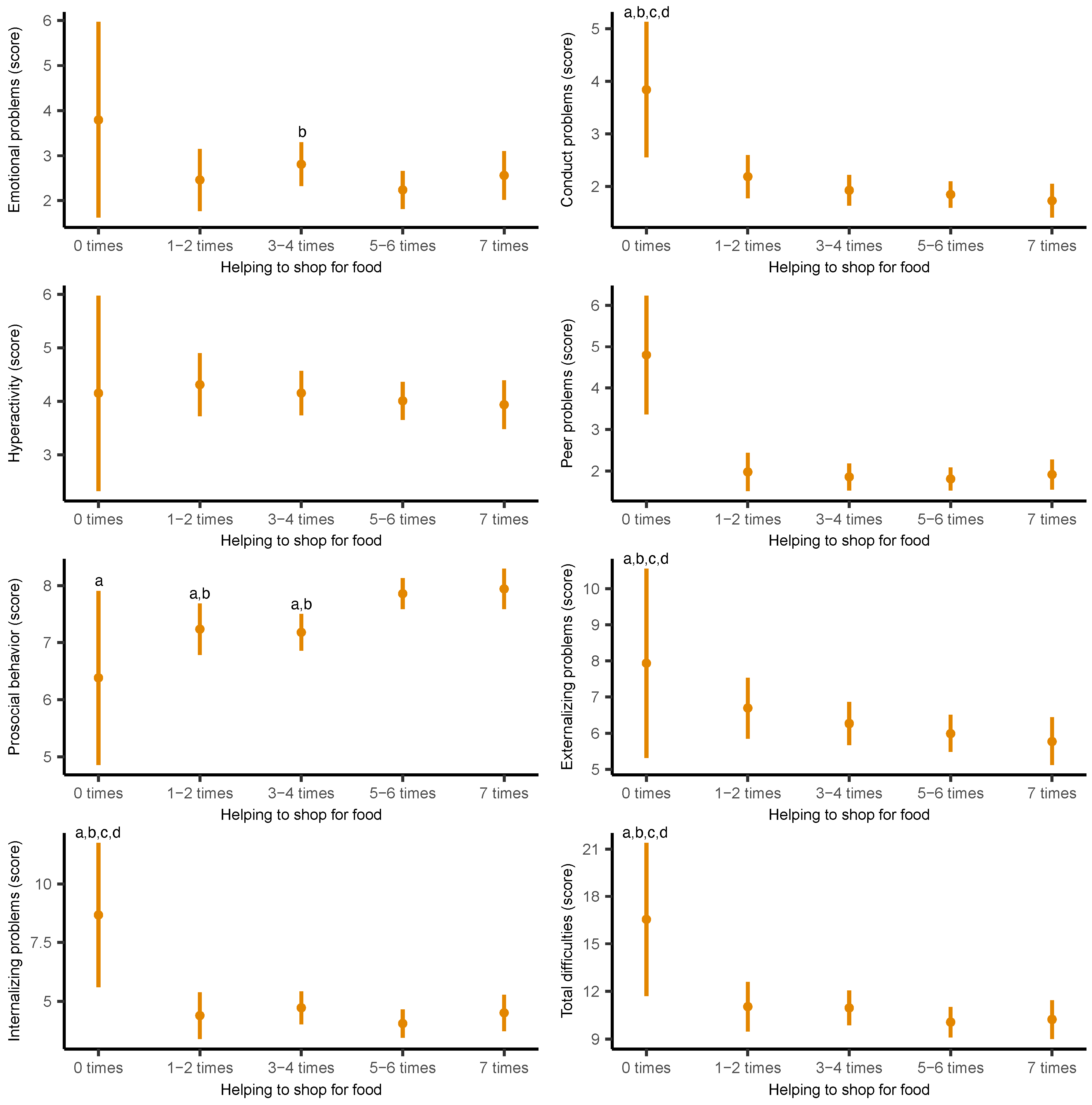

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rahman, M.A.; Kundu, S.; Christopher, E.; Ahinkorah, B.O.; Okyere, J.; Uddin, R.; Mahumud, R.A. Emerging burdens of adolescent psychosocial health problems: A population-based study of 202,040 adolescents from 68 countries. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Committee on the Neurobiological and Socio-behavioral Science of Adolescent Development and Its Applications; Board on Children, Youth, and Families; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The Promise of Adolescence: Realizing Opportunity for All Youth; Bonnie, R.J., Backes, E.P., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25388 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Koch, M.K.; Mendle, J.; Beam, C. Psychological Distress amid Change: Role Disruption in Girls during the Adolescent Transition. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2020, 48, 1211–1222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mental Health of Adolescents; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- McCurdy, B.H.; Scozzafava, M.D.; Bradley, T.; Matlow, R.; Weems, C.F.; Carrion, V.G. Impact of anxiety and depression on academic achievement among underserved school children: Evidence of suppressor effects. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 26793–26801. [Google Scholar]

- Schlack, R.; Peerenboom, N.; Neuperdt, L.; Junker, S.; Beyer, A.-K. The Effects of Mental Health Problems in Childhood and Adolescence in Young Adults: Results of the KiGGS Cohort; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://edoc.rki.de/handle/176904/9117 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Martin Romero, M.Y.; Francis, L.A. Youth involvement in food preparation practices at home: A multi-method exploration of Latinx youth experiences and perspectives. Appetite 2020, 144, 104439. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, L.S.; Khan, R.; Sultana, M.; Soltana, N.; Siddiqua, Y.; Khondker, R.; Sultana, S.; Tumilowicz, A. Using a gender lens to understand eating behaviours of adolescent females living in low-income households in Bangladesh. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12841. [Google Scholar]

- Silván-Ferrero, M.D.P.; Bustillos López, A. Benevolent Sexism Toward Men and Women: Justification of the Traditional System and Conventional Gender Roles in Spain. Sex Roles 2007, 57, 607–614. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, P. Child and Adolescent Time Use and Well-Being: A Study of Current Debates and Empirical Evidence; Open Science Framework: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://osf.io/9qmrk (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Kroska, A. Investigating Gender Differences in the Meaning of Household Chores and Child Care. J. Marriage Fam. 2003, 65, 456–473. [Google Scholar]

- Arafa, A.; Yasui, Y.; Kkubo, Y.; Kato, Y.; Matsumoto, C.; Teramoto, M.; Nosaka, S.; Korigima, M. Lifestyle Behaviors of Childhood and Adolescence: Contributing Factors, Health Consequences, and Potential Interventions. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, W.; Fu, J.; Tian, X.; Tian, J.; Yang, Y.; Fan, W.; Du, Z.; Jin, Z. Physical Fitness and Dietary Intake Improve Mental Health in Chinese Adolescence Aged 12–13. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 921605. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil, A.; Quirk, S.E.; Housden, S.; Brennan, S.L.; Williams, L.J.; Pasco, J.A.; Berk, M.; Jacka, F.N. Relationship Between Diet and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e31–e42. [Google Scholar]

- Utter, J.; Denny, S.; Lucassen, M.; Dyson, B. Adolescent Cooking Abilities and Behaviors: Associations with Nutrition and Emotional Well-Being. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 35–41.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Berge, J.M.; MacLehose, R.F.; Larson, N.; Laska, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Family Food Preparation and Its Effects on Adolescent Dietary Quality and Eating Patterns. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barreiro-Álvarez, M.F.; Latorre-Millán, M.; Bach-Faig, A.; Fornieles-Deu, A.; Sánchez-Carracedo, D. Family meals and food insecurity in Spanish adolescents. Appetite 2024, 195, 107214. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, N.; Touchton-Leonard, K.; Ross, A. Psychosocial Benefits of Cooking Interventions: A Systematic Review. Health Educ. Behav. 2018, 45, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G.; Peralta, L.R. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, N.; Cotter, E.W. Well-Being and Cooking Behavior: Using the Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment (PERMA) Model as a Theoretical Framework. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 560578. [Google Scholar]

- Selman, S.B.; Dilworth-Bart, J.E. Routines and child development: A systematic review. J. Fam. Theo. Revie. 2024, 16, 272–328. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, M.; O’Kane, C.; Issartel, J.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Gaul, D.; Wolfson, J.A.; Lavelle, F. Guidelines for designing age-appropriate cooking interventions for children: The development of evidence-based cooking skill recommendations for children, using a multidisciplinary approach. Appetite 2021, 161, 105125. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, K.G. Rising rates of depression in today’s society: Consideration of the roles of effort-based rewards and enhanced resilience in day-to-day functioning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2006, 30, 497–510. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/94384 (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Kucharczuk, A.J.; Oliver, T.L.; Dowdell, E.B. Social media’s influence on adolescents′ food choices: A mixed studies systematic literature review. Appetite 2021, 168, 105765. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0195666321006723?via%3Dihub (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Blanchard, L.; Conway-Moore, K.; Aguiar, A.; Önal, F.; Rutter, H.; Helleve, A.; Nwosu, E.; Falcone, J.; Savona, N.; Boyland, E.; et al. Associations between social media, adolescent mental health, and diet: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.; Koo, H.C.; Mukhtar, F.; Yim, H. Culinary Nutrition Education Improves Home Food Availability and Psychosocial Factors Related to Healthy Meal Preparation Among Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.; Kaur, S.; Koo, H.C.; Yap, R.; Mukhtar, F. Influences of psychosocial factors and home food availability on healthy meal preparation. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16 (Suppl. S3), e13054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, F.; McGowan, L.; Hollywood, L.; Surgenor, D.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Caraher, M.; Raats, M.; Dean, M. The development and validation of measures to assess cooking skills and food skills. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Laska, M.N.; Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Story, M. Does involvement in food preparation track from adolescence to young adulthood and is it associated with better dietary quality? Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1150–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, P.L.; Gonçalves, C.; Fleary, S.A. Psychosocial correlates in patterns of adolescent emotional eating and dietary consumption. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285446. [Google Scholar]

- Alfaro-González, S.; Garrido-Miguel, M.; Martínez-Vizcaíno, V.; López-Gil, J.F. Mediterranean Dietary Pattern and Psychosocial Health Problems in Spanish Adolescents: The EHDLA Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawon, M.S.R.; Rouf, R.R.; Jahan, E.; Hossain, F.B.; Mahmood, S.; Gupta, R.D.; Islam, M.I.; Al Kibria, G.M.; Islam, S. The burden of psychological distress and unhealthy dietary behaviours among 222,401 school-going adolescents from 61 countries. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21894. [Google Scholar]

- Fismen, A.-S.; Aarø, L.E.; Thorsteinsson, E.; Ojala, K.; Samdal, O.; Helleve, A.; Eriksson, C. Associations between eating habits and mental health among adolescents in five nordic countries: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2640. [Google Scholar]

- López-Gil, J.F. The Eating Healthy and Daily Life Activities (EHDLA) Study. Children 2022, 9, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.I.; Story, M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Food Preparation and Purchasing Roles among Adolescents: Associations with Sociodemographic Characteristics and Diet Quality. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2006, 106, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ortuño-Sierra, J.; Aritio-Solana, R.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Mental health difficulties in children and adolescents: The study of the SDQ in the Spanish National Health Survey 2011–2012. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Currie, C.; Molcho, M.; Boyce, W.; Holstein, B.; Torsheim, T.; Richter, M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Family Affluence Scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, I.; Ballart, J.; Pastor, G.; Jordá, E. Validation of a short questionnaire on frequency of dietary intake: Reproducibility and validity. Nutr. Hosp. 2008, 3, 242–252. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Welk, G.J. Validity and Calibration of the Youth Activity Profile. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143949. [Google Scholar]

- Segura-Díaz, J.M.; Barranco-Ruiz, Y.; Saucedo-Araujo, R.G.; Aranda-Balboa, M.J.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Migueles, J.H.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Ortega, F.B.; Welk, G.J.; Herrador-Colmenero, M.; et al. Feasibility and reliability of the Spanish version of the Youth Activity Profile questionnaire (YAP-Spain) in children and adolescents. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 801–807. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M.E.; Norris, M.L.; Obeid, N.; Fu, M.; Weinstangel, H.; Sampson, M. Systematic review of the effects of family meal frequency on psychosocial outcomes in youth. Can. Fam. Physician 2015, 61, e96–e106. [Google Scholar]

- Snuggs, S.; Harvey, K. Family Mealtimes: A Systematic Umbrella Review of Characteristics, Correlates, Outcomes and Interventions. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, M.; Wu, X.; Xiao, Q.; Luo, J.; Jia, P. Grocery store access and childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e12945. [Google Scholar]

- Abeykoon, A.H.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Muhajarine, N. Health-related outcomes of new grocery store interventions: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2236–2248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, S.; Benkenstein, M. Together always better? The impact of shopping companions and shopping motivation on adolescents’ shopping experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. Adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Appetite 2016, 107, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuroko, S.; Black, K.; Chryssidis, T.; Finigan, R.; Hann, C.; Haszard, J.; Jackson, R.; Mahn, K.; Robinson, C.; Thomson, C.; et al. Create Our Own Kai: A Randomised Control Trial of a Cooking Intervention with Group Interview Insights into Adolescent Cooking Behaviours. Nutrients 2020, 12, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.; Kaur, S.; Koo, H.C.; Mukhtar, F. Involvement of children in hands-on meal preparation and the associated nutrition outcomes: A scoping review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2022, 35, 350–362. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Horst, K.; Smith, S.; Blom, A.; Catalano, L.; Costa, A.I.D.A.; Haddad, J.; Cunningham-Sabo, L. Outcomes of Children’s Cooking Programs: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2024, 56, 881–892. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, C.B.; Greene, K.M.; McHale, S.M. Housework time from middle childhood through adolescence: Links to parental work hours and youth adjustment. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 2071–2084. [Google Scholar]

- Kandola, A.; Lewis, G.; Osborn, D.P.J.; Stubbs, B.; Hayes, J.F. Depressive symptoms and objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behaviour throughout adolescence: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 262–271. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhoff, E.; Keller, R. Age-Specific Life Skills Education in School: A Systematic Review. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 660878. [Google Scholar]

- Singla, D.R.; Waqas, A.; Hamdani, S.U.; Suleman, N.; Zafar, S.W.; Zill-E-Huma; Saeed, K.; Servili, C.; Rahman, A. Implementation and effectiveness of adolescent life skills programs in low- and middle-income countries: A critical review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2020, 130, 103402. [Google Scholar]

- Black, K.; Thomson, C.; Chryssidis, T.; Finigan, R.; Hann, C.; Jackson, R.; Robinson, C.; Toldi, O.; Skidmore, P. Pilot Testing of an Intensive Cooking Course for New Zealand Adolescents: The Create-Our-Own Kai Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anouk Francine, J.G.; Andreas, H. The associations of dietary habits with health, well-being, and behavior in adolescents: A cluster analysis. Child Care Health Dev. 2022, 49, 497–507. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.S.N.; Chen, J.Y.; Ng, M.Y.C.; Yeung, M.H.Y.; Bedford, L.E.; Lam, C.L.K. How Does the Family Influence Adolescent Eating Habits in Terms of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices? A Global Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utter, J.; Denny, S.; Peiris-John, R.; Moselen, E.; Dyson, B.; Clark, T. Family Meals and Adolescent Emotional Well-Being: Findings from a National Study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 67–72.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi, M.; Fan, L.; Myruski, S.; Yang, W.; Keller, K.L.; Nayga, R.M. Online food advertisements and the role of emotions in adolescents’ food choices. Can. J. Agri. Econ. Can. Agroecon. 2024, 72, 45–76. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | N = 634 1 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14.0 (13.0, 15.0) |

| Sex | |

| Boys | 273 (43.0%) |

| Girls | 361 (57.0%) |

| FAS-III (score) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) |

| Overall sleep duration (minutes) | 501 (459, 531) |

| YAP-S physical activity (score) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.1) |

| YAP-S sedentary behaviors (score) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 2609 (1965, 3469) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.7 (19.3, 25.1) |

| Helping to prepare food for dinner | |

| Never | 6 (0.9%) |

| One or two times | 36 (5.7%) |

| Three or four times | 120 (19.0%) |

| Five or six times | 325 (51.0%) |

| Seven times | 147 (23.0%) |

| Helping to shop for food | |

| Never | 6 (0.9%) |

| One or two times | 67 (11.0%) |

| Three or four times | 154 (24.0%) |

| Five or six times | 274 (43.0%) |

| Seven times | 133 (21.0%) |

| Emotional problems (SDQ score) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) |

| Conduct problems (SDQ score) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| Hyperactivity (SDQ score) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) |

| Peer problems (SDQ score) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| Prosocial behavior (SDQ score) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) |

| Externalizing problems (SDQ score) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) |

| Internalizing problems (SDQ score) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) |

| Total difficulties (SDQ score) | 11.0 (7.0, 16.0) |

| Variable | Never (n = 6) | One or Two Times (n = 36) | Three or Four Times (n = 120) | Five or Six Times (n = 325) | Seven Times (n = 147) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 13.5 (13.0, 15.0) | 13.0 (12.0, 14.0) | 14.0 (13.0, 15.0) | 14.0 (13.0, 15.0) | 14.0 (12.0, 15.0) |

| Sex | |||||

| Boys | 3.0 (50.0%) | 20.0 (55.6%) | 59.0 (49.2%) | 142.0 (43.7%) | 49.0 (33.3%) |

| Girls | 3.0 (50.0%) | 16.0 (44.4%) | 61.0 (50.8%) | 183.0 (56.3%) | 98.0 (66.7%) |

| FAS-III (score) | 8.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 10.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 10.0) |

| Overall sleep duration (minutes) | 407.1 (407.1, 522.9) | 503.6 (458.6, 537.9) | 492.9 (450.0, 518.6) | 501.4 (458.6, 531.4) | 505.7 (467.1, 535.7) |

| YAP-S physical activity (score) | 2.6 (2.4, 2.9) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.1) | 2.6 (2.1, 2.9) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.1) | 2.7 (2.3, 3.1) |

| YAP-S sedentary behaviors (score) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.6) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.2) | 2.6 (2.1, 3.0) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.8) |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 5556.1 (3752.0, 8205.6) | 2614.4 (1777.0, 3662.4) | 2581.8 (1977.7, 3316.8) | 2589.3 (1973.1, 3400.9) | 2694.1 (1887.9, 3788.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.9 (18.8, 22.6) | 21.1 (18.3, 24.2) | 21.8 (19.5, 25.1) | 21.6 (19.0, 24.8) | 22.4 (19.6, 26.8) |

| Helping to shop for food | |||||

| Never | 6.0 (100.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) |

| One or two times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 13.0 (36.1%) | 21.0 (17.5%) | 25.0 (7.7%) | 8.0 (5.4%) |

| Three or four times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 10.0 (27.8%) | 55.0 (45.8%) | 78.0 (24.0%) | 11.0 (7.5%) |

| Five or six times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 10.0 (27.8%) | 32.0 (26.7%) | 182.0 (56.0%) | 50.0 (34.0%) |

| Seven times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 3.0 (8.3%) | 12.0 (10.0%) | 40.0 (12.3%) | 78.0 (53.1%) |

| Emotional problems (SDQ score) | 5.5 (3.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (2.0, 6.0) |

| Conduct problems (SDQ score) | 5.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 2.0 (0.5, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| Hyperactivity (SDQ score) | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (2.5, 5.0) | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) |

| Peer problems (SDQ score) | 5.5 (4.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.5) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) |

| Prosocial behavior (SDQ score) | 6.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 8.0 (6.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (6.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 9.0 (7.0, 10.0) |

| Externalizing problems (SDQ score) | 9.0 (6.0, 11.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 10.0) | 7.0 (4.0, 9.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 9.0) |

| Internalizing problems (score) | 10.5 (9.0, 13.0) | 6.0 (2.0, 10.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 9.0) |

| Total difficulties (SDQ score) | 19.5 (14.0, 24.0) | 12.0 (8.0, 15.0) | 12.0 (7.0, 15.5) | 11.0 (7.0, 15.0) | 12.0 (8.0, 17.0) |

| Variable | Never (n = 6) | One or Two Times (n = 67) | Three or Four Times (n = 154) | Five or Six Times (n = 274) | Seven Times (n = 133) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 13.5 (13.0, 15.0) | 14.0 (13.0, 15.0) | 14.0 (13.0, 16.0) | 14.0 (13.0, 15.0) | 14.0 (12.0, 15.0) |

| Sex | |||||

| Boys | 3.0 (50.0%) | 35.0 (52.2%) | 73.0 (47.4%) | 111.0 (40.5%) | 51.0 (38.3%) |

| Girls | 3.0 (50.0%) | 32.0 (47.8%) | 81.0 (52.6%) | 163.0 (59.5%) | 82.0 (61.7%) |

| FAS-III (score) | 8.0 (6.0, 8.0) | 9.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (6.0, 9.0) |

| Overall sleep duration (minutes) | 407.1 (407.1, 522.9) | 492.9 (454.3, 518.6) | 492.9 (454.3, 522.9) | 505.7 (467.1, 540.0) | 497.1 (454.3, 531.4) |

| YAP-S physical activity (score) | 2.6 (2.4, 2.9) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.0) | 2.6 (2.2, 2.9) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.1) | 2.7 (2.3, 3.2) |

| YAP-S sedentary behaviors (score) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.6) | 2.8 (2.4, 3.4) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.0) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.8) |

| Energy intake (kcal) | 5556.1 (3752.0, 8205.6) | 2831.4 (1882.0, 3509.8) | 2507.2 (1954.7, 3301.6) | 2583.9 (1994.5, 3410.5) | 2788.9 (1936.1, 3548.1) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.9 (18.8, 22.6) | 21.2 (19.6, 24.1) | 22.5 (19.1, 25.6) | 21.3 (19.1, 24.8) | 21.8 (19.6, 26.4) |

| Helping to prepare food for dinner | |||||

| Never | 6.0 (100.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 0.0 (0.0%) |

| One or two times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 13.0 (19.4%) | 10.0 (6.5%) | 10.0 (3.6%) | 3.0 (2.3%) |

| Three or four times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 21.0 (31.3%) | 55.0 (35.7%) | 32.0 (11.7%) | 12.0 (9.0%) |

| Five or six times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 25.0 (37.3%) | 78.0 (50.6%) | 182.0 (66.4%) | 40.0 (30.1%) |

| Seven times | 0.0 (0.0%) | 8.0 (11.9%) | 11.0 (7.1%) | 50.0 (18.2%) | 78.0 (58.6%) |

| Emotional problems (SDQ score) | 5.5 (3.0, 7.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.5 (1.0, 6.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 5.0) | 3.0 (1.0, 6.0) |

| Conduct problems SDQ (score) | 5.0 (2.0, 5.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) |

| Hyperactivity (SDQ score) | 5.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 5.0) |

| Peer problems (SDQ score) | 5.5 (4.0, 6.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) | 2.0 (1.0, 4.0) |

| Prosocial behavior (SDQ score) | 6.0 (5.0, 8.0) | 8.0 (6.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (6.0, 9.0) | 8.0 (7.0, 9.0) | 9.0 (7.0, 10.0) |

| Externalizing problems (SDQ score) | 9.0 (6.0, 11.0) | 7.0 (4.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) |

| Internalizing problems (SDQ score) | 10.5 (9.0, 13.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 4.5 (2.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 9.0) |

| Total difficulties (SDQ score) | 19.5 (14.0, 24.0) | 11.0 (8.0, 16.0) | 11.5 (8.0, 16.0) | 11.0 (7.0, 15.0) | 11.0 (7.0, 16.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castillo-Miñaca, M.E.; Mendoza-Gordillo, M.J.; Ruilova, M.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H.; Olivares-Arancibia, J.; Andrade, S.; Ochoa-Avilés, A.; Tárraga-López, P.J.; López-Gil, J.F. Is Involvement in Food Tasks Associated with Psychosocial Health in Adolescents? The EHDLA Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142273

Castillo-Miñaca ME, Mendoza-Gordillo MJ, Ruilova M, Yáñez-Sepúlveda R, Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Olivares-Arancibia J, Andrade S, Ochoa-Avilés A, Tárraga-López PJ, López-Gil JF. Is Involvement in Food Tasks Associated with Psychosocial Health in Adolescents? The EHDLA Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(14):2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142273

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo-Miñaca, Mónica E., María José Mendoza-Gordillo, Marysol Ruilova, Rodrigo Yáñez-Sepúlveda, Héctor Gutiérrez-Espinoza, Jorge Olivares-Arancibia, Susana Andrade, Angélica Ochoa-Avilés, Pedro Juan Tárraga-López, and José Francisco López-Gil. 2025. "Is Involvement in Food Tasks Associated with Psychosocial Health in Adolescents? The EHDLA Study" Nutrients 17, no. 14: 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142273

APA StyleCastillo-Miñaca, M. E., Mendoza-Gordillo, M. J., Ruilova, M., Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R., Gutiérrez-Espinoza, H., Olivares-Arancibia, J., Andrade, S., Ochoa-Avilés, A., Tárraga-López, P. J., & López-Gil, J. F. (2025). Is Involvement in Food Tasks Associated with Psychosocial Health in Adolescents? The EHDLA Study. Nutrients, 17(14), 2273. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17142273