Abstract

Background: Eating disorders (EDs) are complex conditions with significant psychological, physical, and economic impacts, prompting national calls to prioritize ED prevention. Despite numerous prevention programs being implemented in Australian schools, no review to date has systematically mapped their scope, design, and outcomes. Aims: This scoping review aimed to map the current landscape of school-based ED prevention programs conducted in Australia. The review focused on their methodological features, participant and school characteristics, data collected, and key findings. Method: Four electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and Scopus) were searched for relevant papers published from 2010 to February 2025. Studies were included if they reported on a school-based ED prevention program targeting Australian students. Data were extracted and narratively synthesized. Results: A total of 23 studies were identified, representing a range of universal and selective prevention programs. Programs varied in design, delivery, and target populations, with most focusing on students in Grades 7–8. Universal media literacy programs like Media Smart showed good outcomes for boys and girls, while several selective programs demonstrated improvements in body image for girls. Interventions targeting boys or using mindfulness approaches often lacked effectiveness or caused unintended harm. Major gaps in the literature include a lack of qualitative research, limited long-term follow-up, and minimal focus on protective factors. Conclusion: While a range of ED prevention programs have been trialed in Australian schools, few have been rigorously evaluated or demonstrated sustained effectiveness. There is a need for developmentally appropriate, gender-sensitive, and culturally inclusive prevention efforts in schools. Future research should use diverse methods, include underrepresented groups, assess long-term outcomes, integrate broader sociocultural factors shaping students’ environment, and consider enhancing protective factors.

1. Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are complex and often chronic conditions associated with significant psychological (e.g., anxiety, mood, and substance use) and physical comorbidities [1], reduced health-related quality of life [2], and elevated mortality rates [3]. In Australia, the economic burden of EDs was estimated at AUD20.8 billion in 2023 [4], underscoring the urgent need for systemic reform. In response, the Australian National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) released a ten-year national strategy advocating for a stepped care model that situates the prevention of EDs as the first component [5].

The NEDC defines prevention as “actions, programs, or policies that aim to reduce modifiable risk factors for eating disorders, and/or bolster protective factors, to reduce the likelihood that a person will experience an eating disorder” [5]. The NEDC further recognizes schools as the “ideal position” to deliver such strategies, particularly those targeting well-established risk factors, which often emerge in adolescence [6]. Alarmingly, ED prevalence rates and body image concerns are highest among school-aged children and youth [4,7,8]. In a national surveillance study of early-onset EDs in Australia, children aged 5–13 years presented with prolonged symptom duration, significant weight loss, and high rates of medical compromise requiring refeeding [9]. Given that adolescence is the peak period of ED onset—and the age of onset is becoming increasingly younger—combined with the severity and burden of ED pathology, we echo the call to action raised by Yager [10] “we need prevention now, more than ever” (p. 729).

1.1. School-Based Prevention Programs

Indeed, three decades of international research efforts have focused on the development and implementation of school-based ED prevention programs [11]. School-based programs tend to focus on reducing individual and socio-environmental risk factors for ED, such as body dissatisfaction, appearance-ideal internalization, and the negative impacts of peers and the media on these factors, and enhancing protective factors such as self-esteem [11]. Programs may be universal, targeting all students, or selective, focusing on at-risk groups such as adolescent girls with heightened body image concerns [12].

Several recently published systematic reviews have examined the effectiveness of school-based ED prevention programs on outcomes such as core ED psychopathology [13,14], body image [15], and mental health indicators [16]. Berry et al. [13] found that media literacy and dissonance-based interventions produced small to medium effects on ED symptomatology immediately after the intervention, with follow-up results ranging from small negative to moderate positive effects. However, the long-term effectiveness of these programs remains inconsistent, especially among school-aged children, where sustained reductions in ED symptomatology have not been reliably observed [13]. Another systematic review found that universal prevention programs led to improvements in body esteem, self-esteem, and appearance-ideal internalization, but not body dissatisfaction, among children [15]. When also considering selective prevention programs, Pursey et al. [14] reported a general trend toward reduced risk factors for EDs, particularly improvements in body image; however, the effects varied significantly across studies. While these reviews provide valuable insights, none have focused exclusively on school-based ED prevention programs implemented in Australia, where cultural and educational contexts may influence program design, delivery, and outcomes.

1.2. Rationale for the Current Review

Taken together, these findings suggest that schools hold considerable promise as a setting for ED prevention, offering broad access to young people during critical developmental windows [17]. While current programs show encouraging short-term outcomes, such as improvements in body image and self-esteem, their long-term effectiveness remains inconsistent. Nonetheless, with further refinement and investment in developmentally appropriate, evidence-based approaches, school-based programs can play a meaningful role in ED prevention efforts.

Despite the growing number of prevention programs implemented in Australia, no review to date has comprehensively mapped the scope, design, and outcomes of school-based ED prevention programs in Australia. Addressing this gap is essential to inform future research, policy, and practice. A scoping review methodology is suitable for this purpose as we aim to map the existing research base and identify gaps in knowledge to inform future Australian research priorities [18].

The research questions guiding our scoping review were as follows:

- What are the key methodological features of the school-based prevention programs (e.g., universal or selective, content, format, mode of delivery, and follow-up)?;

- What are the demographic and general characteristics of the schools and participants involved in these studies (e.g., age, grade, gender, ethnicity, and location)?;

- What outcome measures or data have been collected in these studies?;

- What are the key findings of available prevention programs based on reported outcome measures?

2. Methods

This scoping review was guided by the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [19], and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [20]. A copy of the PRISMA checklist is included as a Supplementary File. This review was supported by funding from the Graduate School of Health, Faculty of Health, University of Technology Sydney.

2.1. Protocol and Registration

An a priori protocol was developed and prospectively registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) available at https://osf.io/kvade (accessed on 28 October 2024). No major deviations from the protocol occurred, aside from a post hoc decision to limit the search to studies published from 2010 onwards. This decision was based on team consensus that earlier studies were often outdated in terms of theoretical frameworks and methodologies, or had already been synthesized in previous reviews.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

To meet the inclusion criteria, studies must target Australian school-aged children or adolescents aged 4–18 years. All types of schooling were considered (e.g., public, private, mainstream, single-sex, and specialized schools). Prevention programs must aim to target ED symptomology and/or modifiable risk factors such as disordered eating, body image, body dissatisfaction, and shape and weight concerns. The intervention may be delivered in any format if it is conducted within a school setting (e.g., computer program, clinician-led, peer-led, or teacher-delivered). Included articles must present original research, whilst reviews, meta-analyses, opinion papers, and conference abstracts were excluded. Finally, articles had to be published from 2010, and accessible in full-text and available in English due to resource limitations.

2.3. Search Strategy

An initial exploratory search of PsycINFO was conducted to identify relevant review articles and inform the development of a comprehensive search strategy. Keywords and index terms from these articles were refined in consultation with an experienced university librarian. The final search strategy was developed for PsycINFO (OVID; see Appendix A) and adapted for three additional databases, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Scopus. The initial search was conducted in October 2024 and re-run in February 2025. Reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews were also screened using citation chaining to identify additional eligible studies.

2.4. Study Selection Process

The identified papers were imported into Covidence software, https://app.covidence.org (accessed on 30 October 2024), where they were de-duplicated and screened against the inclusion criteria. At the title and abstract level, one reviewer (SS) screened all articles, whilst a second reviewer (SLB) independently screened 20% of the papers to verify accuracy. The reviewers achieved 98% agreement at this stage, with any disagreements resolved through team discussion. At the full-text screening stage, both reviewers (SS and SLB) independently assessed all articles against the inclusion criteria and reached 95% inter-rater agreement.

2.5. Data Charting and Presentation

A data-charting table was created in Covidence and used to extract data items from included papers. This included bibliographical information, study aims and design, population characteristics, school characteristics, intervention characteristics, outcome measures collected, and key findings. For this review, co-educational and boys-only prevention programs were classified as universal, whilst girls-only programs were classified as selective prevention. This classification was guided by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) framework, which defines universal prevention as targeting the general population regardless of risk, and selective prevention as targeting subgroups at elevated risk [21]. Given that boys are not considered a high-risk group in the eating disorder literature, and boys-only programs were delivered in general school settings without screening for risk, which aligns with the IOM definition. Extracted data are presented in tabular format below and accompanied by a descriptive synthesis of results.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

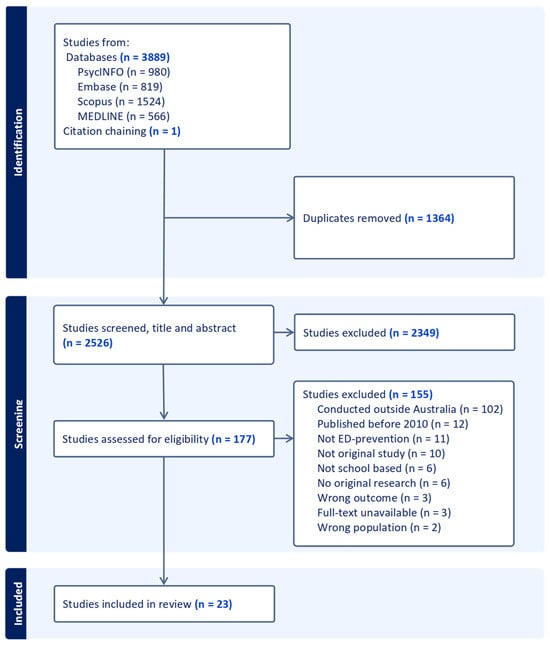

The screening and study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1. A total of 3889 records were identified through database searches, and one record through citation chaining. Of these articles, 1364 were removed as duplicates. After initial screening of 2526 articles, 177 papers were examined at the full-text level, and 155 of these were excluded. A total of 23 studies from 22 articles were included in the final review, as one article is a multi-study paper. Additionally, one RCT was accompanied by a secondary mediator analysis and moderator analysis, which were included due to their relevance to the original RCT intervention.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process.

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of the included studies, including each intervention’s aim and design, sample size, school setting and location, participant demographics, and method of delivery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies.

3.3. Synthesis of Results

Table 2 provides a summary of the intervention characteristics, duration, and follow-up, data collected, and key findings from each source of evidence. The narrative synthesis below is structured around the four guiding research questions, with findings grouped by the program approach.

Table 2.

Outcomes of included studies.

3.3.1. What Are the Key Methodological Features of the School-Based Prevention Programs?

A total of 23 studies were included in this review. The most common study design was randomized controlled trials (RCTs; n = 11), followed by quasi-experimental studies (n = 10) and secondary analyses of RCTs (n = 2). These studies evaluated a range of prevention programs targeting ED risk factors, including cognitive dissonance-based interventions (n = 3), media literacy programs (n = 6), multi-component interventions addressing multiple ED risk factors (n = 8), mindfulness-based approaches (n = 3), self-esteem enhancement programs (n = 2), and healthy lifestyle promotion (n = 1).

In terms of prevention level, twelve studies implemented universal prevention programs in co-educational settings. Three studies delivered body image programs exclusively targeting boys, while seven studies focused on selective prevention for girls. Two studies included both a selective (girls-only) arm and a universal (co-educational or boys-only) comparison group. Delivery was primarily facilitated by external professionals (n = 16), followed by teachers (n = 6), peers (n = 1), and video presentations (n = 1). Session lengths ranged from brief 15 min modules to 90 min weekly sessions, with most programs delivered over 3 to 10 sessions. Follow-up periods were similarly variable: seven studies included a 3-month follow-up, while others extended to 6, 9, or 12 months. Four studies did not include any follow-up assessment.

3.3.2. What Are the Demographic and General Characteristics of the Schools and Participants Involved in These Studies?

The 23 studies were conducted across more than 74 schools in five Australian states, with the majority based in Victoria and South Australia, and additional representation from.

Queensland, New South Wales, and Western Australia. Most schools were situated in urban or suburban areas, although specific classifications (e.g., rural or regional) were not consistently reported.

Participants were primarily students in Grades 7–8 (n = 14), followed by those in Grades 9–12 (n = 6), and Grades K–6 (n = 3). Grade level was not reported in two studies. Ethnicity and cultural background were also inconsistently reported across studies. Where data were available, most samples were predominantly Caucasian, with proportions ranging from 62% to 84%. Several studies reported participants’ country of birth as a proxy for cultural background, with between 64% and 90% of participants born in Australia.

3.3.3. What Outcome Measures or Data Have Been Collected in These Studies?

A wide range of outcome measures was used to assess program effectiveness and feasibility. Data collection instruments that were commonly used to assess ED risk and related constructs included the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q; 10 studies; [44]), the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ; 9 studies; [45]), and the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ; 13 studies; [46]), particularly the thin-ideal internalization subscale. Thirteen studies also evaluated program implementation and feasibility via teacher or student feedback. These included measures of student and teacher acceptability, fidelity to program content, and perceived value. A subset of studies explored additional behavioral and contextual factors, such as screen time, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake, and attitudes toward supplement and steroid use. These exploratory measures were more common in programs with a broader health promotion or media literacy focus. Notably, no studies employed structured clinical interviews or diagnostic tools to assess ED onset as an outcome variable.

3.3.4. What Are the Key Findings of Available Prevention Programs?

Dissonance-Based Interventions

Of the 23 prevention studies included in this review, three studies utilized a cognitive-dissonance approach to target appearance-ideal internalization [22,30,43]. Whilst all three interventions drew from The Body Project [47], there was variability in the population focus, session structure, and delivery method among studies.

One study by Atkinson and Wade [22] employed an RCT design to compare outcomes of a three-session dissonance-based program, a mindfulness program, and a control group for adolescent girls in grades 10–12. When delivered by an expert facilitator, the dissonance-based program led to a reduction in sociocultural pressures at the 6-month follow-up [22]. Whilst dissonance programs often target thin-ideal internalization in at-risk girls, Yager et al. [43] evaluated a program (Goodform) specifically designed to address the muscular ideal and discourage anabolic steroid and supplement use in adolescent boys. Regardless of study conditions, boys’ muscularity dissatisfaction, appearance pressures, and positive attitudes towards steroid use all increased over the approximately eight-week study period.

A third study by Kristoffersen et al. [30] explored the acceptability and feasibility of a video-based dissonance intervention compared to a self-compassion video among adolescents aged 15–17. While more boys than girls reported applying dissonance-based techniques at one-week follow-up, boys in the dissonance group also experienced a significant reduction in positive mood.

Media Literacy Interventions

Six studies employed a media literacy approach, which aims to enhance students’ critical thinking about appearance-focused content and media-driven appearance ideals. Among these, four studies evaluated the Media Smart program, a teacher-delivered intervention designed to target media internalization (investment in appearance-ideals promoted in the media) [48]. In an initial pilot study, Media Smart was found to reduce feelings of ineffectiveness and weight-related peer teasing among both boys and girls post-intervention, with sustained improvements in peer teasing reported at 6-month follow-up [38]. In a subsequent, RCT, Media Smart was compared to two alternative school-based programs—Life Smart, a healthy lifestyle and obesity prevention program, and HELPP, a multi-risk factor program adapted from Happy Being Me (HBM)—as well as a no-intervention control group [39]. Results showed that girls who completed Media Smart reported fewer eating concerns than those in the HELPP group at 6 months follow-up, and fewer weight and shape concerns than those in the Life Smart group at 12-month follow-up [39]. Boys who participated in Media Smart demonstrated improvements in body dissatisfaction, media internalization, weight-related peer teasing, and perfectionism, with sustained benefits in media internalization and depression at both 6- and 12-month follow-ups [39]. In contrast, boys in the Life Smart program experienced increased media internalization and higher levels of depression at follow-up, despite some initial improvements in body dissatisfaction [39]. To better understand for whom the programs were most effective, Wilksch et al. [40] used moderation analysis, and their results indicated that students with higher baseline shape and weight concerns who completed either the Life Smart or HELPP interventions reported increased eating concerns and meal skipping at follow-up compared to those who completed Media Smart [40]. Mediator analysis conducted by Wade et al. [41] further identified media internalization as a key mechanism underlying improvements in body image across both Media Smart and Life Smart programs.

Two additional studies extended the traditional media literacy approaches to the unique context of social media [26,33]. Girls who participated in the Boost social media literacy program exhibited improvements in body esteem, dietary restraint, and media literacy compared to control participants [33]. Similarly, Gordon et al. [26] assessed the universal SoMe program in a large multi-school RCT. Gender-specific effects were observed where girls in the SoMe group reported significantly lower levels of dietary restraint at 6-month follow-up, while boys showed increased self-esteem but also a greater drive for muscularity at 12-month follow-up [26].

Multicomponent Prevention Programs

Multicomponent prevention programs typically target one or more modifiable risk factors and may integrate different theoretical approaches to ED prevention. Three studies included in this study evaluated HBM, which addresses both individual ED risk factors via a media literacy approach as well as the influence of the peer environment on body image [24,34,35]. Improvements in thin-ideal internalization, body comparisons, appearance-related conversations with peers, body satisfaction, dietary restraint, and self-esteem were observed when HBM was delivered as a selective intervention with adolescent girls [35]. To better understand the active components of the program, McLean et al. [34] conducted a dismantling study that separated and compared the media literacy and appearance comparison content of HBM. Girls in the HBM-comparison group experienced improvements in bulimic symptoms and thin-ideal internalization, while the HBM-media group showed some improvements in appearance comparisons [34]. Importantly, Dunstan et al. [24] found that HBM was comparably effective for girls when delivered in a co-educational context.

Building on the HBM framework, Dove Confident Me (DCM) was developed through co-design with adolescents, educators, and experts to enhance relevance and engagement. In an evaluation, Forbes et al. [25] found that adolescent girls who participated in DCM reported higher sociocultural pressures compared to the control group immediately post-intervention, but also demonstrated greater reductions in social comparisons by three-month follow-up. However, qualitative feedback from teachers indicated low student engagement and limited perceived efficacy, prompting revisions to the program content [25]. Despite these modifications, girls continued to report elevated sociocultural pressure and thin-ideal internalization post-test, the latter also maintained at follow-up [25].

Another selective prevention program, Y’s Girl, addressed topics such as cultural beauty practices, body positivity, communication skills, positive self-talk, and media literacy [36]. Grade 6 girls in the Y’s Girl group experienced significant improvements in body satisfaction and self-esteem, and reductions in body size discrepancy, thin-ideal internalization, and body comparisons, particularly amongst girls with initially high levels of body comparison and low self-esteem [36].

The Healthy Me program adopted a gender-sensitive approach by delivering sessions separately to boys and girls, addressing the distinct sociocultural pressures each gender faces [32]. Both boys and girls reported increased body and muscle esteem at follow-up [32]. Additionally, boys demonstrated higher physical activity levels and reduced endorsement of masculine gender norms, while girls showed improvements in fruit and vegetable intake [32].

Lastly, the Life Smart program was a mixed-gender universal program targeting multiple obesity and ED risk factors by promoting a holistic approach to health [37]. Student feedback indicated that boys rated the healthy eating topic most favorably, while girls preferred the sleep and exercise lessons [37]. Further, girls in the Life Smart group experienced improved shape and weight concern at post-intervention, while boys showed a small to moderate increase in physical activity [37].

Mindfulness-Based Programs

Three studies evaluated mindfulness-based prevention programs delivered universally to high school students. Each program utilized mindfulness strategies and practices aimed to address transdiagnostic risk factors purported to underpin a range of psychopathologies, including EDs. Whilst there was high acceptability of the .b Mindfulness in Schools program amongst students and teachers, no improvements were found in psychological outcomes at post-intervention or follow-up [27]. Indeed, higher levels of anxiety were reported by boys, and those with low baseline shape and weight concern and low baseline depression in the intervention group compared to the control [27]. The authors hypothesized that the mindfulness concepts may be developmentally inappropriate for younger adolescents in the study and that longer sessions with longer mindfulness practice could improve outcomes. Subsequently, Johnson and Wade [28] piloted the Mindfulness Training for Teens program, which is closely modeled on adult mindfulness programs. There were moderate improvements in depression and anxiety for Year 10 students compared to the control at follow-up, but no changes in weight and shape concerns [28]. A subsequent RCT tested a revised version of the program with shorter sessions and the removal of a 10 min break [29]. Again, no significant improvements were found in psychological outcomes compared to the control group. Notably, an age-related effect emerged where Year 8 students in the intervention group reported declines in mindfulness and wellbeing at three-month follow-up, while Year 10 students showed no significant changes over time [29].

Self-Esteem Enhancement

This review identified two studies that focused on improving self [31] and body esteem [23]. Adolescent boys 11–15 years old did not experience any improvements in body image or body satisfaction after a three-lesson self-esteem program [31]. In a younger population of children aged 5–8, Damiano et al. [23] evaluated the teacher-led Achieving Body Confidence for Young Children (ABC-4-YC) intervention. The pilot study found significant improvements in children’s body esteem following the three-lesson program [23].

Healthy Lifestyle Promotion

One study in this review utilized a healthy lifestyle promotion approach to enhance body satisfaction in a cohort of adolescent boys [42]. The ATLAS program educates boys on drug and supplement use, the benefits of strength training, and sports nutrition using a peer-facilitated model. While the program led to small, non-significant improvements in both functional and esthetic body image satisfaction, qualitative feedback indicated that students found the content on avoiding anabolic steroids and drugs more engaging than appearance-focused material [42].

4. Discussion

This scoping review sought to identify and describe school-based ED prevention programs implemented in Australia, with a focus on their methodologies, participants, outcomes, and findings. Overall, the review revealed that while a range of distinct universal and selective programs have been trialed, only a small number of programs have been evaluated across studies, and few have demonstrated sustained effectiveness across genders and developmental stages. These results underscore the need to critically examine not only what programs are being implemented, but also how, for whom, and under what conditions they are most effective.

The review identified a predominance of quantitative methodologies, often examining program feasibility or efficacy. Demographic reporting across the studies was markedly limited, significantly constraining the ability to assess sample diversity and generalizability. Only three studies reported student ethnicity, while 61% omitted cultural or ethnic data entirely and 26% reported only place of birth, providing minimal insight into the cultural composition of the samples. The majority of participants across the reviewed studies were in Grades 7–8, aligning with evidence suggesting that early adolescence (age 12–13) is a critical window for effective ED prevention [49]. Programs targeting this age group may be more impactful due to the developmental timing of body image concerns and the onset of sociocultural pressures. This contrasts with earlier findings by Stice et al. [50] which suggested greater effectiveness among older adolescents. The current review supports the shift toward earlier intervention, particularly when programs incorporate media literacy, self-esteem building, and peer influence components. However, the limited number of studies involving younger children or older teens highlights a need for more age-diverse research to determine how prevention strategies can be tailored across developmental stages.

Among the programs reviewed, Media Smart emerged as an effective universal prevention program. The program was associated with improvements in body dissatisfaction, media internalization, and depressive symptoms among boys, and reductions in eating concerns and weight and shape dissatisfaction among girls [39]. These findings align with meta-analytic evidence from Le et al. [51], which identified media literacy as the only approach to consistently yield small to moderate effect sizes in co-educational settings. Importantly, Media Smart also supports the feasibility of teacher-led delivery, which may enhance program scalability. However, the broader literature presents mixed findings regarding the effectiveness of teacher-led versus researcher-led implementation [14,15,52], and many teachers report lacking the training and institutional support necessary for confident delivery [53]. As suggested by surveyed teachers, a multimodal delivery model combining teacher facilitation with external expertise may offer a more sustainable and scalable solution [53].

Gender-specific patterns in program outcomes were also evident. Universal programs such as SoMe [26] and Healthy Me [32] demonstrated differential effects, with girls benefiting from reduced dietary restraint and healthier eating behaviors, while boys showed increased self-esteem but also, in some cases, a heightened drive for muscularity. These findings underscore the importance of gender-sensitive content and delivery formats. Selective programs targeting adolescent girls, such as Happy Being Me [24,34,35] and Y’s Girl [36] consistently improved body image outcomes and self-esteem, particularly among those with higher baseline vulnerability. In contrast, interventions designed specifically for boys, such as Goodform [43] and Self-esteem and Healthy Body Image Program [31], failed to produce significant improvements in body image or related behaviors. In some cases, participation was linked to unintended negative effects, such as reduced positive mood or increased appearance pressures.

While universal programs are often critiqued for yielding non-significant statistical outcomes, Yager [10] argues that such programs should not be dismissed when they are theoretically grounded and show no evidence of harm. This perspective is particularly relevant in school settings, where educators may rely on unvetted or improvised resources to deliver well-intentioned body image lessons. However, the presence of iatrogenic effects in some programs challenges the assumption that all prevention is benign and highlights the need for careful program selection and monitoring.

4.1. Clinical and Theoretical Implications

This review highlights several clinical and theoretical implications in the current landscape of school-based ED prevention in Australia. First, many programs continue to adopt an individual-level focus, targeting proximal risk factors such as body dissatisfaction and thin-ideal internalization, while underemphasizing broader sociocultural determinants. As Piran [54,55] have argued, prevention efforts that neglect the influence of systemic factors—such as gender norms, socioeconomic status, and cultural marginalization, risk oversimplifying the etiology of body image concerns and disordered eating. This critique has gained increasing interest due to the divergent etiological pathways between genders and the gendered outcomes evident in this study [56]. In a qualitative paper, Atkinson et al. [57] identified a pressing need to shift the field’s focus from individual and lower-level sociocultural factors to higher-level systems that shape appearance ideals and body image concerns for young people. For example, broader cultural shifts in masculine gender roles add further complexity to our understanding of how boys experience and respond to appearance pressures. Programs that fail to account for these evolving sociocultural dynamics may struggle to engage male participants meaningfully or produce lasting change.

Second, a critical theoretical and methodological issue in ED prevention research is the distinction between risk reduction and true prevention. Most of the studies included in this review were appropriately framed as risk reduction trials, focusing on proximal outcomes such as body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, and thin-ideal internalization. While these are important targets, they do not equate to the prevention of clinically diagnosable EDs. As Becker [58] argues, the medical standard for prevention requires evidence of reduced onset of EDs, which demands large samples, long-term follow-up, and diagnostic interviews—conditions rarely met in school-based research. Stice et al. [59] further highlight the statistical challenges of detecting differences in ED onset due to the low base rate of these disorders and the reduced power of dichotomous outcome analyses. Notably, no studies employed diagnostic interviews or assessed ED onset as an outcome, nor included follow-up periods beyond 12 months. This limits the ability to draw conclusions about the long-term or clinical impact of these programs.

Third, the field remains heavily focused on risk reduction, with minimal attention to protective factors, as only one study [23] explicitly targeted self-esteem enhancement. As Levine and Smolak [60] argue, protective factors can buffer against a range of risks. The near-total absence of such approaches represents a missed opportunity to shift from a deficit-based model to one that fosters resilience and wellbeing. A recent exception is the Embrace Kids Classroom Program (EKCP), a school-based, positive psychology intervention targeting self-esteem, mindfulness, and body appreciation [61]. While showing positive impacts on self-compassion, the program faced some resistance from school communities due to its inclusion of gender diversity content, reflecting broader societal stigma around gender discourse.

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

This scoping review has some methodological limitations. First, data charting was completed by a single review, which may have introduced bias or inconsistencies in data extraction. Second, the review did not include gray literature such as reports and university theses, meaning relevant school-based programs may have been excluded, thus limiting the comprehensiveness of the findings. Finally, no formal critical appraisal of the included studies was undertaken, which limits our ability to comment on their methodological rigor. It is recommended that future reviews on this topic aim to address these limitations and extend upon the findings of this study by employing a systematic review methodology and applying a risk-of-bias assessment tool.

Despite these limitations, the findings presented by this review highlight some important gaps in the current literature on this topic and highlight important areas for future investigation. For example, this review highlights that there is a growing number of distinct body image prevention programs, with over two dozen having been trialed in Australian schools; however, only a handful have been evaluated across multiple studies. A notable limitation of the current literature is the absence of published evaluations for several widely implemented Australian-based programs, including the Butterfly Foundation’s BodyKind and Body Bright programs, which are currently being delivered in Australian primary and high schools. The absence of published effectiveness data for these widely implemented programs reflects a broader evidence gap in prevention research, underscoring the need for real-world evaluations. Future research should aim to address this gap in the literature. Additionally, the variable effectiveness and adverse effects of some programs, like mindfulness interventions, highlight the need for developmentally tailored content. Researchers should consider age-appropriate content and delivery formats to ensure that interventions align with the developmental stage and emotional maturity of students at different ages. Furthermore, this review identifies a need for interventions that explicitly enhance protective factors against body dissatisfaction; an important avenue for future exploration

Given the limited demographic reporting revealed in this review, future studies should also adopt more detailed demographic reporting practices. Comprehensive data on students’ cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds are essential to assess the inclusivity and generalizability of findings and to ensure that prevention efforts are equitable and relevant across diverse student populations.

Finally, this review identified a notable absence of qualitative and mixed-methods research. The lack of studies exploring the lived, phenomenological experiences of young people engaging with prevention programs represents a missed opportunity to acquire a deeper understanding of how and why interventions succeed or fail. As Ciao et al. [62] argue, “we need to make space for multiple forms of quantitative and qualitative knowledge in our conception of what is ‘evidence-based.’” Incorporating diverse methodologies could enrich the evidence base and ensure that programs are not only effective but also meaningful and contextually relevant to participants.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review provides a comprehensive synthesis of school-based ED prevention programs implemented in Australia since 2010. The findings highlight a range of program approaches trialed, including cognitive dissonance, media literacy, multicomponent risk factor reduction, mindfulness, self-esteem enhancement, and healthy lifestyle promotion. The prevention programs reviewed varied in design, delivery, and target populations, with most focusing on students in Grades 7–8. Our review found that universal media literacy programs like Media Smart showed promising outcomes for boys and girls, while several selective programs demonstrated improvements in body image for girls. While a range of ED prevention programs have been trialed in Australian schools, our review identified that few have been rigorously evaluated or demonstrated sustained effectiveness. Our findings highlight the need for future research to investigate developmentally appropriate, gender-sensitive, and culturally inclusive prevention efforts in schools.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu17132118/s1, PRISMA Checklist included as a Supplementary File.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., A.L.B. and S.L.B.; methodology, S.S. and S.L.B.; data extraction, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.S., A.L.B. and S.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review was supported by funding from the Graduate School of Health at the University of Technology, Sydney.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Gadigal and the Wangal peoples of the Eora nation, upon whose ancestral lands this research was conducted. We pay our utmost respect to Elders past and present. The authors acknowledge the Graduate School of Health within the Faculty of Health at the University of Technology, Sydney, for the funding to support this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

APA PsycINFO Search Strategy

- eating disorder*.mp. or exp Eating Disorders/

- binge eating.mp. or exp binge eating/

- muscle dysmorphi*.mp. or exp muscle dysmorphia/

- (other specified feeding and eating).mp.

- emotional eating.mp. or exp emotional eating/

- exercise dependence.mp. or exp exercise dependence/

- body image.mp. or Body Image/

- 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

- early intervention.mp. or exp Early Intervention/

- prevent*.mp. or exp Prevention/

- universal prevention.mp.

- selective prevention.mp.

- 9 or 10 or 11 or 12

- exp Schools/or school*.mp.

- 8 and 13 and 14

- limit 15 to english language

References

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Psychiatric and Medical Correlates of DSM-5 Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of Adults in the United States. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, P.; Mitchison, D.; Collado, A.E.L.; González-Chica, D.A.; Stocks, N.; Touyz, S. Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life of Eating Disorders, Including Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in the Australian Population. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskovic-Wheatley, J.; Bryant, E.; Ong, S.H.; Vatter, S.; Le, A.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; et al. Eating Disorder Outcomes: Findings from a Rapid Review of over a Decade of Research. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deloitte Access Economics. Paying the Price, Second Edition: The Economic and Social Impact of Eating Disorders in Australia; Deloitte Access Economics: Sydney, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC). National Eating Disorders Strategy 2023–2033; NEDC: Sydney, Australia, 2023.

- National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC). Eating Disorders in Schools: Prevention, Early Identification, Response and Recovery Support; NEDC: Sydney, Australia, 2023.

- Pastore, M.; Indrio, F.; Bali, D.; Vural, M.; Giardino, I.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M. Alarming Increase of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2023, 263, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparti, C.; Santomauro, D.; Cruwys, T.; Burgess, P.; Harris, M. Disordered Eating among Australian Adolescents: Prevalence, Functioning, and Help Received. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.; Elliott, E.; Madden, S. Early-Onset Eating Disorders in Australian Children: A National Surveillance Study Showing Increased Incidence. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1838–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z. Something, Everything, and Anything More than Nothing: Stories of School-Based Prevention of Body Image Concerns and Eating Disorders in Young People. Eat. Disord. 2024, 32, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z.; O’Dea, J.A. School-Based Prevention. In The Wiley Handbook of Eating Disorders; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 569–581. ISBN 978-1-118-57408-9. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council; Institute of Medicine. Defining the Scope of Prevention. In Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders Among Young People: Progress and Possibilities; Boat, T., O’Connell, M.E., Warner, K.E., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, S.L.; Burton, A.L.; Rogers, K.; Lee, C.M.; Berle, D.M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Eating Disorder Preventative Interventions in Schools. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2025, 33, 390–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.M.; Burrows, T.L.; Barker, D.; Hart, M.; Paxton, S.J. Disordered Eating, Body Image Concerns, and Weight Control Behaviors in Primary School Aged Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Universal–Selective Prevention Interventions. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 1730–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, J.Y.X.; Tam, W.; Shorey, S. Research Review: Effectiveness of Universal Eating Disorder Prevention Interventions in Improving Body Image among Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.; Chan, B.N.K.; Lai, S.I.; Tung, K.T.S. School-Based Eating Disorder Prevention Programmes and Their Impact on Adolescent Mental Health: Systematic Review. BJPsych Open 2024, 10, e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, J.M.; Cheng, T.L.; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Opportunities for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in Schools. In Launching Lifelong Health by Improving Health Care for Children, Youth, and Families; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024; ISBN 978-0-6488488-2-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Prevention of Mental Disorders. Reducing Risks for Mental Disorders: Frontiers for Preventive Intervention Research; Mrazek, P.J., Haggerty, R.J., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-309-04939-9. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Wade, T.D. Does Mindfulness Have Potential in Eating Disorders Prevention? A Preliminary Controlled Trial with Young Adult Women. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2016, 10, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, S.R.; Yager, Z.; McLean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J. Achieving Body Confidence for Young Children: Development and Pilot Study of a Universal Teacher-Led Body Image and Weight Stigma Program for Early Primary School Children. Eat. Disord. J. Treat. Prev. 2018, 26, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunstan, C.J.; Paxton, S.J.; McLean, S.A. An Evaluation of a Body Image Intervention in Adolescent Girls Delivered in Single-Sex versus Co-Educational Classroom Settings. Eat. Behav. 2017, 25, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.; Paxton, S.; Yager, Z. Independent Pragmatic Replication of the Dove Confident Me Body Image Program in an Australian Girls Independent Secondary School. Body Image 2023, 46, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.S.; Jarman, H.K.; Rodgers, R.F.; McLean, S.A.; Slater, A.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M.; Paxton, S.J. Outcomes of a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of the Some Social Media Literacy Program for Improving Body Image-Related Outcomes in Adolescent Boys and Girls. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Burke, C.; Brinkman, S.; Wade, T. Effectiveness of a School-Based Mindfulness Program for Transdiagnostic Prevention in Young Adolescents. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Wade, T. Piloting a More Intensive 8-week Mindfulness Programme in Early- and Mid-adolescent School Students. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Wade, T. Acceptability and Effectiveness of an 8-Week Mindfulness Program in Early- and Mid-Adolescent School Students: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 2473–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, M.; Johnson, C.; Atkinson, M.J. Feasibility and Acceptability of Video-Based Microinterventions for Eating Disorder Prevention among Adolescents in Secondary Schools. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, M.P.; Ricciardelli, L.A.; Karantzas, G. Impact of a Healthy Body Image Program among Adolescent Boys on Body Image, Negative Affect, and Body Change Strategies. Body Image 2010, 7, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.P.; Connaughton, C.; Tatangelo, G.; Mellor, D.; Busija, L. Healthy Me: A Gender-Specific Program to Address Body Image Concerns and Risk Factors among Preadolescents. Body Image 2017, 20, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.A.; Wertheim, E.H.; Masters, J.; Paxton, S.J. A Pilot Evaluation of a Social Media Literacy Intervention to Reduce Risk Factors for Eating Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, S.A.; Wertheim, E.H.; Marques, M.D.; Paxton, S.J. Dismantling Prevention: Comparison of Outcomes Following Media Literacy and Appearance Comparison Modules in a Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, S.M.; Paxton, S.J. An Evaluation of a Body Image Intervention Based on Risk Factors for Body Dissatisfaction: A Controlled Study with Adolescent Girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Paxton, S.J.; Rodgers, R.F. Y’s Girl: Increasing Body Satisfaction among Primary School Girls. Body Image 2013, 10, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilksch, S.M.; Wade, T.D. Life Smart: A Pilot Study of a School-Based Program to Reduce the Risk of Both Eating Disorders and Obesity in Young Adolescent Girls and Boys. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilksch, S.M. School-Based Eating Disorder Prevention: A Pilot Effectiveness Trial of Teacher-Delivered Media Smart. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2015, 9, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilksch, S.M.; Paxton, S.J.; Byrne, S.M.; Austin, S.B.; Thompson, K.M.; Dorairaj, K.; Wade, T.D. Prevention Across the Spectrum: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Three Programs to Reduce Risk Factors for Both Eating Disorders and Obesity. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilksch, S.M.; Paxton, S.J.; Byrne, S.M.; Austin, S.B.; O’Shea, A.; Wade, T.D. Outcomes of Three Universal Eating Disorder Risk Reduction Programs by Participants with Higher and Lower Baseline Shape and Weight Concern. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, T.D.; Wilksch, S.M.; Paxton, S.J.; Byrne, S.M.; Austin, S.B. Do Universal Media Literacy Programs Have an Effect on Weight and Shape Concern by Influencing Media Internalization? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z.; McLean, S.A.; Li, X. Body Image Outcomes in a Replication of the ATLAS Program in Australia. Psychol. Men Masc. 2019, 20, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z.; Doley, J.R.; McLean, S.A.; Griffiths, S. Goodform: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial of a School-Based Program to Prevent Body Dissatisfaction and Muscle Building Supplement Use Among Adolescent Boys. Body Image 2023, 44, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Beglin, S.J. Assessment of Eating Disorders: Interview or Self-Report Questionnaire? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1994, 16, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for Assessment of Restrained, Emotional, and External Eating Behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.K.; van den Berg, P.; Roehrig, M.; Guarda, A.S.; Heinberg, L.J. The Sociocultural Attitudes towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and Validation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 35, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Marti, C.N.; Spoor, S.; Presnell, K.; Shaw, H. Dissonance and Healthy Weight Eating Disorder Prevention Programs: Long-Term Effects from a Randomized Efficacy Trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilksch, S.M.; Tiggemann, M.; Wade, T.D. Impact of Interactive School-based Media Literacy Lessons for Reducing Internalization of Media Ideals in Young Adolescent Girls and Boys. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006, 39, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, Z.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Ricciardelli, L.A.; Halliwell, E. What Works in Secondary Schools? A Systematic Review of Classroom-Based Body Image Programs. Body Image 2013, 10, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E.; Shaw, H.; Marti, C.N. A Meta-Analytic Review of Eating Disorder Prevention Programs: Encouraging Findings. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 3, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, L.K.-D.; Barendregt, J.J.; Hay, P.; Mihalopoulos, C. Prevention of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 53, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusina, J.R.; Exline, J.J. Beyond Body Image: A Systematic Review of Classroom-Based Interventions Targeting Body Image of Adolescents. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 4, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.M.; Hart, M.; Hure, A.; Cheung, H.M.; Ong, L.; Burrows, T.L.; Yager, Z. The Needs of School Professionals for Eating Disorder Prevention in Australian Schools: A Mixed-Methods Survey. Children 2022, 9, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piran, N. A Feminist Perspective on Risk Factor Research and on the Prevention of Eating Disorders. Eat. Disord. 2010, 18, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piran, N. A Feminist Perspective on the Prevention of Eating Disorders. In The Wiley Handbook of Eating Disorders; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 582–596. ISBN 978-1-118-57408-9. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S.B.; Rieger, E.; Karlov, L.; Touyz, S.W. Masculinity and Femininity in the Divergence of Male Body Image Concerns. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Stock, N.M.; Alleva, J.M.; Jankowski, G.S.; Piran, N.; Riley, S.; Calogero, R.; Clarke, A.; Rumsey, N.; Slater, A.; et al. Looking to the Future: Priorities for Translating Research to Impact in the Field of Appearance and Body Image. Body Image 2020, 32, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.B. Our Critics Might Have Valid Concerns: Reducing Our Propensity to Conflate. Eat. Disord. 2016, 24, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stice, E.; Onipede, Z.A.; Marti, C.N. A Meta-Analytic Review of Trials That Tested Whether Eating Disorder Prevention Programs Prevent Eating Disorder Onset. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 87, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.P.; Smolak, L. Protective Factors. In The Prevention of Eating Problems and Eating Disorders: Theories, Research, and Applications; Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 251–266. ISBN 978-1-315-40105-8. [Google Scholar]

- Granfield, P.; Kemps, E.; Johnson, C.; Seekis, V.; Prichard, I. A Pilot Evaluation of the Acceptability and Feasibility of, and Preliminary Outcomes from, the Embrace Kids Classroom Program among Australian Pre-Adolescents. Body Image 2025, 52, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciao, A.C.; Brown, T.A.; Levine, M. Future Directions for Equity-Centered Body Image and Eating Disorders Prevention Work. Eat. Disord. 2024, 32, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).