Developing a Framework for Culturally Sensitive Breastfeeding Interventions: A Community Needs Assessment of Breastfeeding Experiences and Practices in a Black Immigrant Community

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Online Survey

3.2. Focus Group Results

3.2.1. Summary of Major Topics

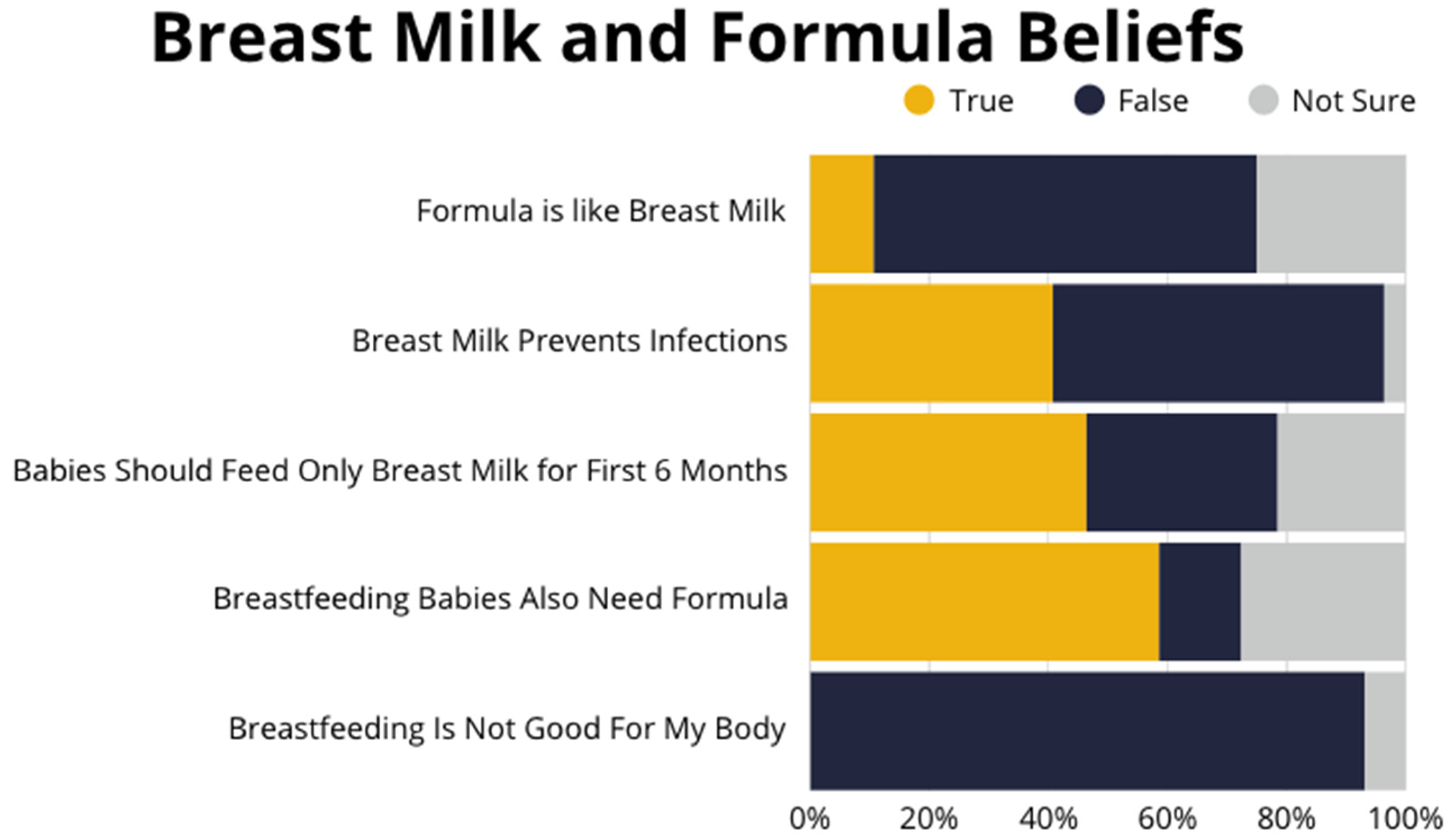

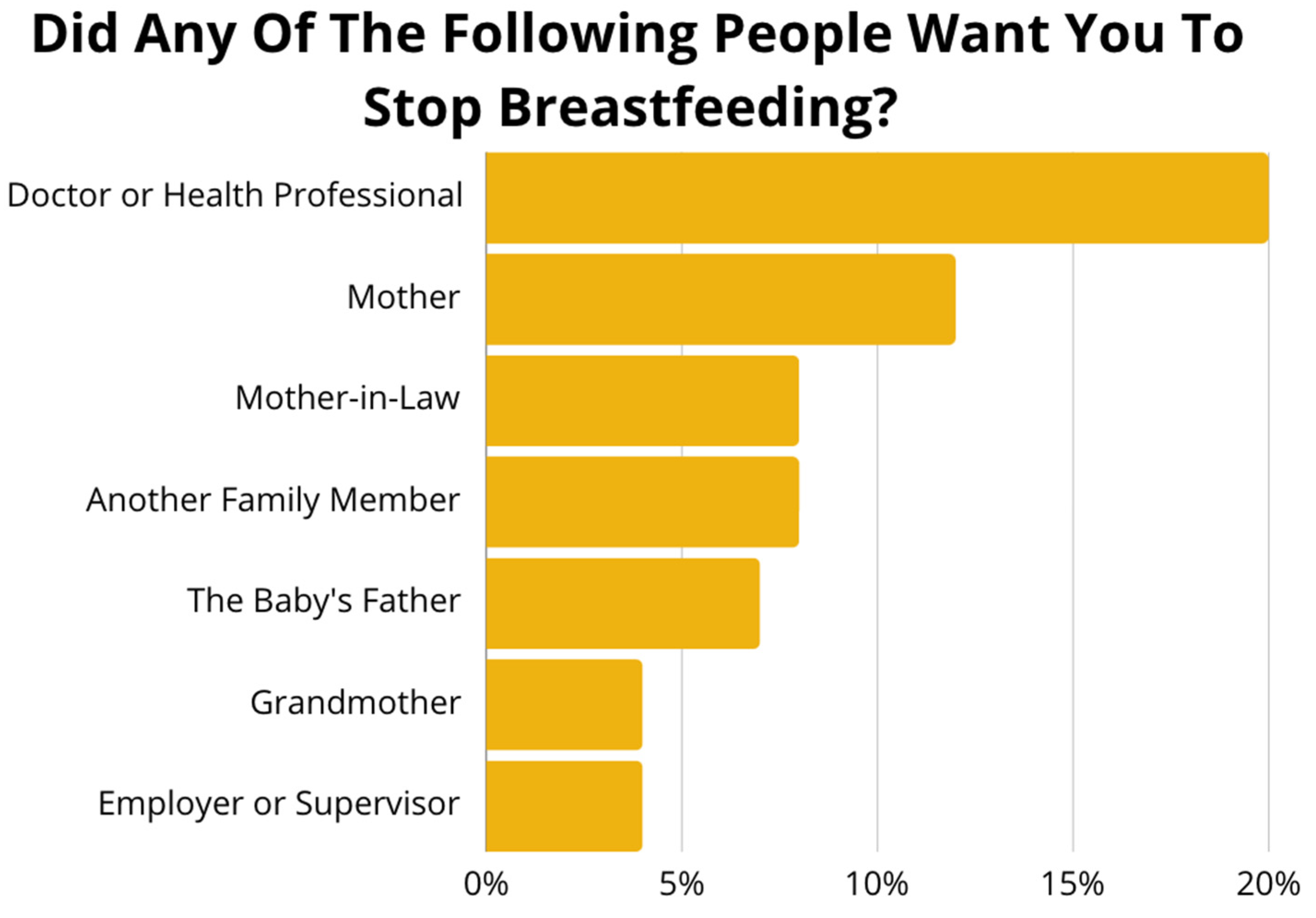

3.2.2. Breastfeeding Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs

“Breastfeeding in my culture is very important because we believe it makes the child stronger and smart.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“I do not see the difference between breast milk and formula. However, when I had my baby in Illinois, I was told about the difference between the two and encouraged to breastfeed. But for me, I don’t see any difference.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“For example, when you go to Walmart with your child and your child is crying and you need to give breast, but you can’t give your child your breast because people will be looking at you weirdly. Like what are you about to do? However, back home you can give your child the breast anywhere in public. And people don’t really care about you feeding your child. But the challenge comes here when you think, “Okay, I’m going to take this baby out, but starts crying I won’t be able to give it breast milk.” So, it’s just better to switch to formula as its comfortable and you don’t have to always worry about giving breast when you are out with the child.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.3. Infant Feeding Practices with Potential to Affect Breastfeeding

“We, as older people, we drink water when we are hot because it makes us to feel good. And the kid too, sometimes they are hot, and they need water to cool down. So why do the doctor always say we should not be giving the kids water? I think it is not okay.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“I had a sister who had a baby here. After delivering the baby [she] got sick. So, she started using the pump because her breasts were filling up. After some time, they were mixing the milk in the freezer with formula. So, the reason they were giving them that [was because] the breast milk was losing some of its nutrition, so they needed to add some formula. So, after I left the hospital, I started doing that too, mixing the formula and the breast milk. I was wondering if that was the right thing to do.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.4. Breastfeeding Support Experiences in Home Country vs. the U.S.

“In Africa we got lots of support from family members and we got a whole lot of time to rest. We had a lot of time to breastfeed our child. But here, based on our occupations and work schedule, we don’t get enough time to breastfeed our child as long as possible.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“So, especially for single mothers. You live by yourself; you take care of all kids by yourself; you don’t have time to go through all that or [have] someone to help you with all of that.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“Back home, we are exposed to so many things that produce milk. The food and stuff to do that is really easy to get. And so that we can have milk. However, here we are lost. We don’t know what to do, what to eat, or how to go about it in order to get milk.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.5. Perception About Inadequate Milk Supply

“My first baby, I breastfed for a year and 8 months, but for the second one I breastfed for a whole year. But this is the first time I am having a baby and every time I give the baby milk, the baby ends up crying without getting enough milk. Now I am wondering—I have tried everything. I have tried to eat vegetables only and things like that. But it is not working, I am still short in my milk. And I don’t understand the cause of that.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“One thing I would like the doctors to do to come up with something that helps us have milk after I have babies. I have noticed since I have come here, every time I have a baby that it is hard for my milk to come out for more than 5 months. I am not sure if it is related to what I am eating. But I would like, at least, for the doctors to tell us what to eat while breastfeeding so that we are able to breastfeed longer. And I have noticed that I am not the only person. I have met a lot of Africans who are having the same issue where the milk does not come out at all, or it doesn’t come out for long. So, if the doctor can at least tell us what to eat and what not to eat. Because I have asked the question before, and I was told that there is nothing—there is no medication to take in that situation. So now, I am wondering what to eat and what not to eat.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.6. Work-Related Breastfeeding Barriers

“The difficulty was work. It was not easy because I had to return to work from early in the morning till late at night. During that time, the baby had to have formula. Or if I pumped and put it in the fridge, they could have that. But it wasn’t easy.”mother from Togo

“Sometimes it is very hard. We are working and the breast gets very big and it’s hurting but we have to keep working like that for 10 h. When we come home, the breast is coming up with so much pressure such that when we give it to the baby the baby starts coughing and they won’t want to take the breast anymore.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“I am afraid of giving my baby my breast milk because it has been in there for so long after work, it goes bad.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.7. Attitude Towards Use of Breast Pump

“I don’t pump at work because I don’t think that’s a good place to do it. I’d have to go do it in the restroom and I don’t think that’s a clean place to do it. I also feel like I don’t have enough time to go pump, so I prefer to do it at home.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“I am sure there is a difference from when the baby is breastfeeding and when I am pumping. I feel like pumping is pulling the breast too hard. And now I am kind of worried that the way it does there will be consequences in the future… Is it not going to cause any breast cancer?”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“Pumping at work is a challenge. Because my workplace has a room where we can go and pump, but we don’t have a fridge to put it in until we finish work.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.8. Attitude Towards Breast Milk Donation and Use of Donor Milk

“Donation is not bad; it is good to give milk for other babies. Because there are some parents who give birth and then they die. But for me, I am alive, so I don’t see myself putting my baby in that situation. Or taking donor milk. It is best for me to just keep trying to give breast milk and if I can’t then I give formula.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“I cannot take somebody else’s breast milk. Instead, I’d take the other option where I wait for the breast milk to come out. I might take some water mixed with sugar and give it to the child until I have breast milk.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.9. Lactation Support and Culturally Sensitive Hospital Care

“I think that preparing someone for breast milk should start when they are pregnant. And, since I have been going to the doctor here when pregnant, I never seen the doctor or nurse discussing breastfeeding.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“When I went to the hospital the doctors ask me if I am going to breastfeed or not. But they did not educate me on why it is important to give breast milk. And I think that when they start doing that more women will be more likely to breastfeed rather than just jumping to formula.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“For my case it was because I had high blood pressure, and the doctor wanted to prescribe a medication and asked me to stop breastfeeding so that I would be able to take the medicine.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

3.2.10. Tailored Community Education Needs

“The doctor might have given them education regarding breastfeeding. But I think the problem is with the translator. Because some translators have an accent or speak a different French than what they do. For example, they might have a Canadian accent, and we are from Congo and a lot of us speak with a Belgian accent, so it is hard for us to understand.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“Many people do not have the culture of reading just because of being busy with kids and other stuff. But if there’s a video then people can just play it in the background.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

“Back home there are groups for women who just had kids… I also think that it shouldn’t be like WIC where they look at your income and you might be ineligible to attend. It should be somewhere where it is free for everyone to come. Like, I didn’t know that I could pump milk and it’s good to stay for up to 4 h. So, I’m just hearing it right now. And I know there are women like me who have never heard about it. That it would be really educational to bring all of them together in one room and try to educate them.”mother from Democratic Republic of Congo

4. Discussion

4.1. Programmatic Implications and Future Directions

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WIC | Women, Infants and Children |

| FGD | Focus group discussions |

Appendix A. Focus Group Transcript Details

Breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs

|

Infant feeding practices with potential to impact breastfeeding

|

Breastfeeding support experiences in home country vs. the United States

|

Perception about inadequate milk supply

|

Work-related breastfeeding barriers

|

Attitude towards the use of breast pumps

|

Attitude towards the use of donor milk

|

Lactation support and culturally sensitive hospital care

|

Tailored community education needs

|

References

- McGowan, C.; Bland, R. The Benefits of Breastfeeding on Child Intelligence, Behavior, and Executive Function: A Review of Recent Evidence. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2023, 18, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.G.; Stellwagen, L.M.; Noble, L.; Kim, J.H.; Poindexter, B.B.; Puopolo, K.M.; Section on Breastfeeding, Committee on Nutrition, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Promoting Human Milk and Breastfeeding for the Very Low Birth Weight Infant. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021054272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, J.Y.; Noble, L. Policy Statement: Breastfeeding and the Use of Human Milk. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022057988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breastfeeding Report Card. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/breastfeeding-report-card/index.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Chiang, K.V.; Li, R.; Anstey, E.H.; Perrine, C.G. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Breastfeeding Initiation—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, K.J.; Nakayama, J.Y.; Chiang, K.V.; Grap, M.E.; Anstey, E.H.; Boundy, E.O.; Hamner, H.C.; Li, R. Disaggregation of Breastfeeding Initiation Rates by Race and Ethnicity—United States, 2020-2021. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2023, 20, E114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breastfeeding Among U.S. Children Born 2014–2021, CDC NIS-Child. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-data/survey/results.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Safon, C.B.; Heeren, T.C.; Kerr, S.M.; Clermont, D.; Corwin, M.J.; Colson, E.R.; Moon, R.Y.; Kellams, A.L.; Hauck, F.R.; Parker, M.G. Disparities in Breastfeeding Among U.S. Black Mothers: Identification of Mechanisms. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safon, C.B.; Heeren, T.; Kerr, S.; Corwin, M.; Colson, E.R.; Moon, R.; Kellams, A.; Hauck, F.R.; Parker, M.G. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Breastfeeding Continuation Among U.S. Hispanic Mothers: Identification of Mechanisms. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2023, 18, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Perrine, C.G.; Anstey, E.H.; Chen, J.; MacGowan, C.A.; Elam-Evans, L.D. Breastfeeding Trends by Race/Ethnicity Among US Children Born From 2009 to 2015. JAMA Pediatr 2019, 173, e193319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, S.; Odems, D.; Ward, L.; Monangi, N.; Shockley-Smith, M.; Previtera, M.; Knox-Kazimierczuk, F.A. Examining the Role of Women, Infant, and Children in Black Women Breastfeeding Duration and Exclusivity: A Systematic Review. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2023, 18, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, S.G.; Arigbede, O.; Mathis, A.; Close, F.; Darling-Reed, S.F. Breastfeeding among Hispanic and Black Women: Barriers and Support. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2023, 4, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, E.C.; Li, R.; Scanlon, K.S.; Perrine, C.G.; Grummer-Strawn, L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e726–e732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odeniyi, A.O.; Embleton, N.; Ngongalah, L.; Akor, W.; Rankin, J. Breastfeeding beliefs and experiences of African immigrant mothers in high-income countries: A systematic review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D.; Vicca, N.; Streiner, S. Breastfeeding beliefs and practices of African women living in Brisbane and Perth, Australia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roess, A.A.; Robert, R.C.; Kuehn, D.; Ume, N.; Ericson, B.; Woody, E.; Vinjamuri, S.; Thompson, P. Disparities in Breastfeeding Initiation Among African American and Black Immigrant WIC Recipients in the District of Columbia, 2007–2019. Am. J. Public Health 2022, 112, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.M.; Kington, S. Research on Black Women and Breastfeeding: Assessing Publication Trends (1980–2020). Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2023, 18, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iowa Counties by Population. World Population Review. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-counties/iowa (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- QuickFacts. Johnson County, Iowa. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/johnsoncountyiowa/PST045224 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- American Immigration Council. Immigrants in Iowa. 2023 Data Year. Available online: https://map.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/locations/iowa/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020–2024. United States Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Iowa Title V Needs Assessment Update. Available online: https://mchb.tvisdata.hrsa.gov/Narratives/III.C.%20Needs%20Assessment%20Update/1e8da53f-da18-4894-a52a-cab7a74f8e4a (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Women, Infants and Children (WIC) Program. Iowa Health and Human Services. Available online: https://hhs.iowa.gov/food-assistance/wic-Iowa (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Culley, L.; Hudson, N.; Rapport, F. Using focus groups with minority ethnic communities: Researching infertility in British South Asian communities. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M.; Kaiser, B.N. Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 292, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, L. Thematic Coding and Analysis. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamner, H.C.; Beauregard, J.L.; Li, R.; Nelson, J.M.; Perrine, C.G. Meeting breastfeeding intentions differ by race/ethnicity, Infant and Toddler Feeding Practices Study-2. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; Reese Masterson, A.; Frieson, T.; Douglass, F.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; O’Connor Duffany, K. Barriers and facilitators to exclusive breastfeeding among Black mothers: A qualitative study utilizing a modified Barrier Analysis approach. Matern. Child Nutr. 2023, 19, e13428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, A.; Siebelt, L.; Marshall, J.L.; Gavine, A.; Girard, L.C.; Symon, A.; MacGillivray, S. Counselling interventions to enable women to initiate and continue breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.; Patel, P.; Wouk, K.G.; Neupane, B.; Alkhalifah, F.; Bartholmae, M.M.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Q. Breastfeeding Perceptions and Decisions among Hispanic Participants in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman-Winter, L.; Szucs, K.; Milano, A.; Gottschlich, E.; Sisk, B.; Schanler, R.J. National Trends in Pediatricians’ Practices and Attitudes About Breastfeeding: 1995 to 2014. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20171229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, B.; Koshy, L.; Neiterman, E. Women’s Perceptions and Experiences of Breastfeeding: A scoping review of the literature. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavle, J.A.; LaCroix, E.; Dau, H.; Engmann, C. Addressing barriers to exclusive breast-feeding in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and programmatic implications. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 3120–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.M.; Kirk, R.; Muzik, M. Overcoming Workplace Barriers: A Focus Group Study Exploring African American Mothers’ Needs for Workplace Breastfeeding Support. J. Hum. Lact. 2015, 31, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, K.; Hansen, K.; Brown, S.; Portratz, A.; White, K.; Dinkel, D. Workplace Breastfeeding Support Varies by Employment Type: The Service Workplace Disadvantage. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2018, 13, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edemba, P.W.; Irimu, G.; Musoke, R. Knowledge attitudes and practice of breastmilk expression and storage among working mothers with infants under six months of age in Kenya. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, F.; Obeng, C.S.; Greene, A.R.; Dennis, B.K.; Wright, B.N. Untold Narratives: Perceptions of Human Milk Banking and Donor Human Milk Among Ghanaian Immigrant Women Living in the United States. J. Racial. Ethn. Health Disparities 2025, 12, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.M.; Namisi, C.P.; Kirabira, N.V.; Lwetabe, M.W.; Rujumba, J. Acceptability to donate human milk among postnatal mothers at St. Francis hospital Nsambya, Uganda: A mixed method study. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2024, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojjanasrirat, W.; Ahmed, A.H.; Johnson, R.; Long, S. Facilitators and Barriers of Human Milk Donation. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child Nurs. 2023, 48, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, L.; Massa, S.; Mallardi, M.; Arcangeli, V.; Serrao, F.; Costa, S.; Vento, G.; Mazza, M.; Simonetti, A.; Janiri, D.; et al. Psychological factors and barriers to donating and receiving milk from human milk banks: A review. Nutrition 2024, 118, 112297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.A.; Becker, G.E. Early additional food and fluids for healthy breastfed full-term infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD006462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, K.G. Nutrition, growth, and complementary feeding of the breastfed infant. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 48, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, J.; Funkquist, E.L.; Grandahl, M. The association between early introduction of tiny tastings of solid foods and duration of breastfeeding. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2023, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Peng, A.; Chen, Y.; Vinturache, A.; Zhang, Y. Trends in Prevalence of Early Introduction of Complementary Foods to US Children, 2016 to 2022. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2440255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Patterson, P.; MacKenzie-Shalders, K.; van Herwerden, L.A.; Bishop, J.; Rathbone, E.; Honeyman, D.; Reidlinger, D.P. Workplace programmes for supporting breast-feeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyamfi, A.; O’Neill, B.; Henderson, W.A.; Lucas, R. Black/African American Breastfeeding Experience: Cultural, Sociological, and Health Dimensions Through an Equity Lens. Breastfeed. Med. Off. J. Acad. Breastfeed. Med. 2021, 16, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Survey Participant Demographics (n = 33) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age | 34 |

| Mean number of children aged 0–2 years | 3 |

| Highest level of education | College: 48% High school: 34% High school or no formal education: 16% |

| Mean number of years lived in the U.S | 5.7 years |

| Married | 97% |

| Insurance Status | Had health insurance: 76% (n = 25) Did not have health insurance: 12% (n = 4) Did not respond: 12% (n = 4) |

| Reason | % of Participants Who Indicated That This was a Very Important Reason for Breastfeeding Cessation |

|---|---|

| (1) Receiving formula/milk from WIC | 52.2 |

| (2) Mother was sick and had to take medicine | 22.7 |

| (3) Baby was hungry a lot of the time | 21.7 |

| (4) Baby was sick and could not breastfeed | 18.2 |

| (5) Not having enough milk production | 16.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Awelewa, T.; Murra, A.; Story, W.T. Developing a Framework for Culturally Sensitive Breastfeeding Interventions: A Community Needs Assessment of Breastfeeding Experiences and Practices in a Black Immigrant Community. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2094. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132094

Awelewa T, Murra A, Story WT. Developing a Framework for Culturally Sensitive Breastfeeding Interventions: A Community Needs Assessment of Breastfeeding Experiences and Practices in a Black Immigrant Community. Nutrients. 2025; 17(13):2094. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132094

Chicago/Turabian StyleAwelewa, Temitope, Alexandra Murra, and William T. Story. 2025. "Developing a Framework for Culturally Sensitive Breastfeeding Interventions: A Community Needs Assessment of Breastfeeding Experiences and Practices in a Black Immigrant Community" Nutrients 17, no. 13: 2094. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132094

APA StyleAwelewa, T., Murra, A., & Story, W. T. (2025). Developing a Framework for Culturally Sensitive Breastfeeding Interventions: A Community Needs Assessment of Breastfeeding Experiences and Practices in a Black Immigrant Community. Nutrients, 17(13), 2094. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132094