Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diets: A Path or Barrier to Food (In)Security?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

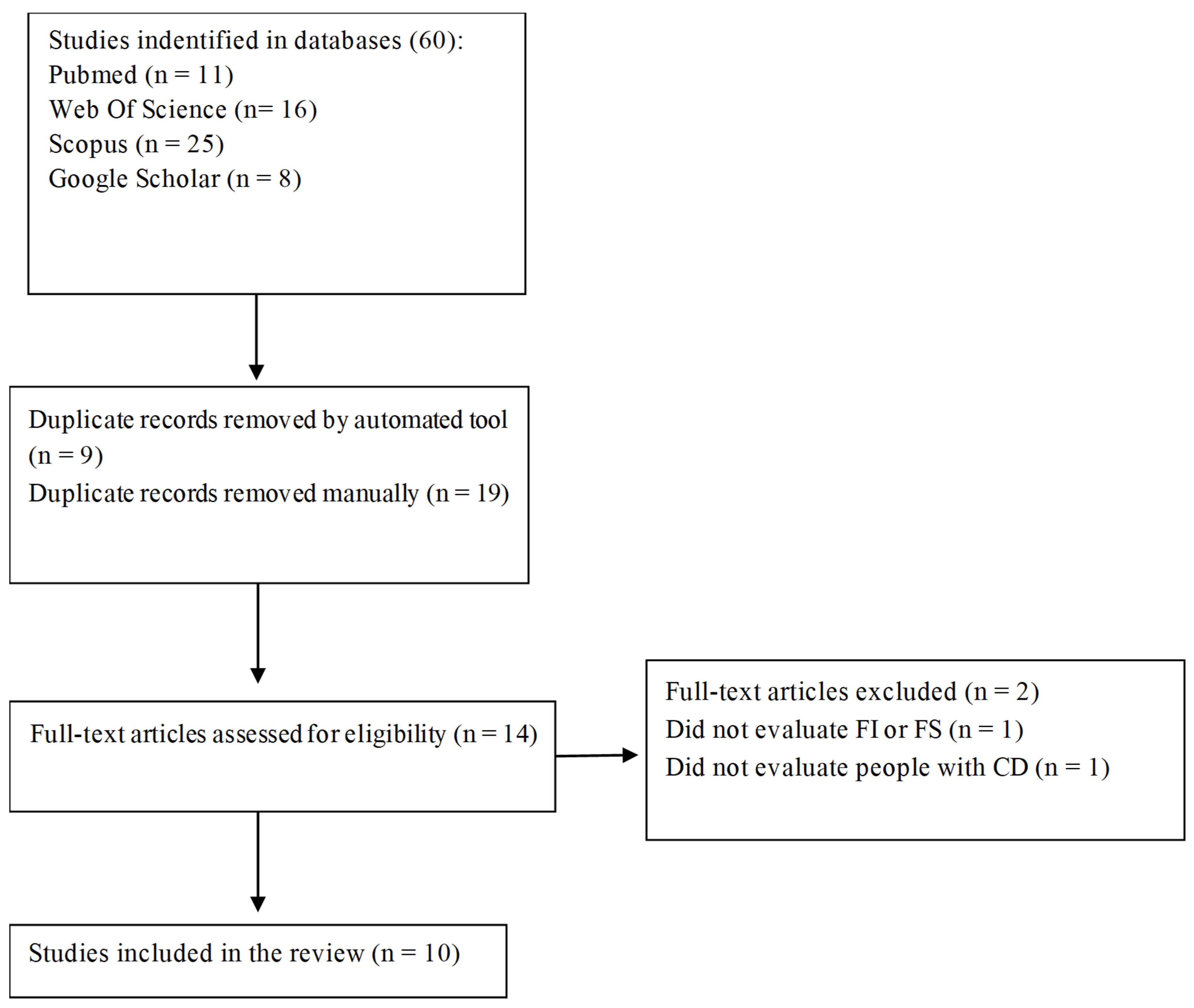

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Studies

3.2. Instruments Used in the Studies

3.3. Food and Nutritional Security and Insecurity Among Celiac Patients

3.4. Factors Related to Food Insecurity in Celiac Disease

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Celiac disease |

| FNI | Food and nutritional insecurity |

| FNS | Food and nutritional security |

| GFD | Gluten-free diet |

References

- Al-Toma, A.; Volta, U.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; Sanders, D.S.; Cellier, C.; Mulder, C.J.; Lundin, K.E.A. European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease (ESsCD) guideline for Coeliac Disease and Other Gluten-Related Disorders. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Catassi, C. Clinical Practice Celiac Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2419–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, P.; Arora, A.; Strand, T.A.; Leffler, D.A.; Catassi, C.; Green, P.H.; Kelly, C.P.; Ahuja, V.; Makharia, G.K. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 16, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, Y. Celiac Disease in Children: A Review of the Literature. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraghikhah, N.; Ashtari, S.; Asri, N.; Shahbazkhani, B.; Al-Dulaimi, D.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Razzaghi, M.R.; Zali, M.R. An Updated Overview of Spectrum of Gluten-Related Disorders: Clinical and Diagnostic Aspects. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, D.; Peña, A.S. Developing Strategies to Improve the Quality of Life of Patients with Gluten Intolerance in Patients with and without Coeliac Disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2012, 23, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galli, G.; Esposito, G.; Lahner, E.; Pilozzi, E.; Corleto, V.D.; Di Giulio, E.; Aloe Spiriti, M.A.; Annibale, B. Histological Recovery and Gluten-Free Diet Adherence: A Prospective 1-Year Follow-up Study of Adult Patients with Coeliac Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, H.; Ruiz-Carnicer, Á.; Segura, V.; Comino, I.; Sousa, C. Challenges of Monitoring the Gluten-Free Diet Adherence in the Management and Follow-Up of Patients with Celiac Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Miaja, M.; José, J.; Martín, D.; Treviño, S.J.; Suárez González, M.; Bousoño García, C. Study of Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet in Coeliac Patients. An. Pediatr. (Engl. Ed.) 2021, 94, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte-Galvez, J.; Vanga, R.R.; Dennis, M.; Hansen, J.; Leffler, D.A.; Kelly, C.P.; Mukherjee, R. Factors Governing Long-Term Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in Adult Patients with Coeliac Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Ficken, C. Cost and Affordability of a Nutritionally Balanced Gluten-Free Diet: Is Following a Gluten-Free Diet Affordable? Nutr. Diet. 2016, 73, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.A.; Ibrahim, M.O.; Alhaj, O.A. Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Anders, S.; Jiang, Z.; Bruce, M.; Gidrewicz, D.; Marcon, M.; Turner, J.M.; Mager, D.R. Food Insecurity Impacts Diet Quality and Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet in Youth with Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Berry, E.M. The Concept of Food Security; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 2, ISBN 9780128126882. [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos, D.; Eivers, A.; Sondergeld, P.; Pattinson, C. Food Insecurity and Child Development: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzo, J.; Haddad, L.; Schneider, K.R.; Béné, C.; Covic, N.M.; Guarin, A.; Herforth, A.W.; Herrero, M.; Sumaila, U.R.; Aburto, N.J.; et al. Viewpoint: Rigorous Monitoring Is Necessary to Guide Food System Transformation in the Countdown to the 2030 Global Goals. Food Policy 2021, 104, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D. Effects of Food and Nutrition Insecurity on Global Health. N. Engl. J. Med. Rev. 2025, 392, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; WHO; UNICEF; WFP. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024—Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 9789251388822. [Google Scholar]

- Wehler, C.A.; Scott, R.I.; Anderson, J.J. The Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project: A Model of Domestic Hunger—Demonstration Project in Seattle, Washington. J. Nutr. Educ. 1992, 24, 29S–35S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Marin-León, L.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Refinement of the Brazilian Household Food Insecurity Measurement Scale: Recommendation for a 14-Item EBIA. Rev. De Nutr. 2014, 27, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, R.; Tandon, S.; Khaouli, M.; Blom, J.; Daca, R.; Verdu, E.; Armstrong, D.; Pinto-Sanchez, M. The impact of food insecurity on adherence to a gluten-free diet in the adult celiac disease population attending a dedicated celiac clinic. Proc. Int. J. Psychol. 2023, 58, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-sunaid, F.F.; Al-homidi, M.M.; Al-qahtani, R.M.; Al-ashwal, R.A.; Mudhish, G.A.; Hanbazaza, M.A.; Al-zaben, A.S. The Influence of a Gluten-Free Diet on Health-Related Quality of Life in Individuals with Celiac Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, N.; Mehrotra, I.; Weisbrod, V.; Regis, S.; Silvester, J.A. Brief Communication: Survey Based Study on Food Insecurity during COVID-19 for Households with Children on a Prescribed Gluten-Free Diet. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, R.; Tandon, S.; Khaouli, M.; Blom, J.-J.; Daca, R.; Verdu, E.F.; Armstrong, D.; Sanchez, M.I.P. Su1338 food insecurity negatively impacts gluten-free diet adherence and is associated with persistent symptoms in adult patients with celiac disease. Proc. Gastroenterol. 2024, 166, S-735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeets, S.M.; Jong, J.C.K.; van der Velde, L.A. Food Insecurity and Other Barriers to Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in Individuals with Celiac Disease and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity in the Netherlands: A Mixed-Methods Study. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e088069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifeh, F.; Riasatian, M.S.; Ekramzadeh, M.; Honar, N.; Jalali, M. Assessing the Prevalence of Food Insecurity among Children with Celiac Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Food Secur. 2019, 7, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Singh, S.; Jairath, V.; Radulescu, G.; Ho, S.K.M.; Choi, M.Y. Food Insecurity Negatively Impacts Gluten Avoidance and Nutritional Intake in Patients With Celiac Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2022, 56, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siminiuc, R.; Ṭurcanu, D. Food Security of People with Celiac Disease in the Republic of Moldova through Prism of Public Policies. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 961827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catassi, C.; Chirdo, F.G. The Gluten-Free Diet: The Road Ahead. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; Palmquist, A.; FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP. Hunger Numbers Stubbornly High for Three Consecutive Years as Global Crises Deepen: UN Report. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-07-2024-hunger-numbers-stubbornly-high-for-three-consecutive-years-as-global-crises-deepen--un-report (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Gatti, S.; Rubio-Tapia, A.; Makharia, G.; Catassi, C. Patient and Community Health Global Burden in a World with More Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2024, 167, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Alshami, I.K.; Al Hourani, H.; Sarhan, W.; Al-holy, M.; Abughoush, M.; Al-awwad, N.J.; Hoteit, M.; Al-jawaldeh, A. Food Insecurity, Dietary Diversity, and Coping Strategies A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaçe, D.; Di Pietro, M.L.; Caprini, F.; de Waure, C.; Ricciardi, W. Prevalence and Correlates of Food Insecurity among Children in High-Income European Countries. A Systematic Review. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 2020, 56, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, C.J.; An, R.; Ellison, B.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Food Insecurity among College Students in the United States: A Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arzhang, P.; Abbasi, S.H.; Sarsangi, P.; Malekahmadi, M.; Nikbaf-Shandiz, M.; Bellissimo, N.; Azadbakht, L. Prevalence of Household Food Insecurity among a Healthy Iranian Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1006543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, F.H.; Sims, A.; van der Pligt, P. Measuring Food Insecurity in India: A Systematic Review of the Current Evidence. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, P.; Zarpoosh, M.; Moradi, S.; Jalili, C. Celiac Disease and COVID-19 in Adults: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzlinger, A.; Branchi, F.; Elli, L.; Schumann, M. Gluten-Free Diet in Celiac Disease—Forever and for All? Nutrients 2018, 10, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo Definitions for Coeliac Disease and Related Terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, S.P.; Hayes, B.; Wilding, H.; Apputhurai, P.; Tye-Din, J.A.; Knowles, S.R. Systematic Review: Exploration of the Impact of Psychosocial Factors on Quality of Life in Adults Living with Coeliac Disease. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 147, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanci, O.; Jeanes, Y.M. Are Gluten-Free Food Staples Accessible to All Patients with Coeliac Disease? Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Wolf, R.L.; Lebwohl, B.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Green, P.H.R. Persistent Economic Burden of the Gluten Free Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, L.; Madden, A.M.; Fallaize, R. An Investigation into the Nutritional Composition and Cost of Gluten-Free versus Regular Food Products in the UK. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Country | Objective | Type of Study | Characterization and Number of Participants | Participants’ Age (Years) | Females (%) | FNI Assessment Tool | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al- Sunaid et al. 2021 [22] | Saudi Arabia | To assess the association between adherence to a GFD, AI, and HRQoL in a cohort of individuals with CD living in Saudi Arabia. | Cohort | Adults (97) | 34 ± 9 | 89% | Food Insecurity Experience Scale Survey Module (FIES-SM) | A total of 62% of participants faced FNI. Individuals living in non-central regions had higher levels of FNI. Gluten-free foods were not available at the supermarket for 53.55%. Additional challenges to accessing gluten-free foods included travel, lack of pita breads, and limited gluten-free options at restaurants. FNI significantly influences the adherence to a GFD and is associated with lower HRQOL in terms of both emotional well-being and mental health. |

| Ma et al., 2021 [27] | US | To systematically evaluate the impact of food security on patients with CD and its association with GFD adoption and nutritional intake in the United States. | Cohort | Adults (200) | 42.1 (17.7 years) | 60.4% | USDA 18-Item Standard Food Security Survey (SFSS) | A total of 15.9% of CD patients live in a food-insecure household. Patients who were food secure were significantly more likely to be on a GFD compared with patients who were food-insecure. FNI is associated with lower adherence to a GFD and significant deficiencies in macronutrient and micronutrient consumption. |

| Du et al., 2022 [23] | US | To better understand FNI in households with a child on a prescribed GFD and how food insecurity may affect GFD adherence during the pandemic. | Cross-sectional | 378 households with CD children | 7 | 61% | Hunger Vital Sign Screener and National Center for Health Statistics US Household 6-Item Short Form Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) | In the pre-pandemic period, specifically about GF foods, 21% of the households were screened for FNI, and 27% were screened during the COVID-19 pandemic. All households reported that the availability of GF foods decreased during the pandemic (p < 0.001). Rural communities had the highest rates of food insecurity and GF FNI. GF food insecurity may pose a health risk by increasing the likelihood of intentional gluten ingestion. |

| Elsahoryi, N.A. et al., 2024 [12] | Jordan | To estimate the relationship between FNI and HRQoL in patients with CD and to assess whether this relationship is mediated or moderated by adherence to GFD. | Cross-sectional | 1162 (adults) | 28.52 ± 8.48 | 72.40% | Food Insecurity Experience Scale Survey Module (FIES-SM) | A total of 79.2% of CD patients in Jordan suffered from severe FNI and 4.9% presented FNS. There is a complicated interplay between FNI and HRQoL in patients with CD that is impacted by several factors, including gender, marital status, and income. |

| Khalifeh, et al., 2019 [26] | Iran | To evaluate the rate of food insecurity in children with CD and to assess its relationship with growth parameters in both genders. | Cross-sectional | 62 (children) | 11.04 (±3.8) | 58.1% | USDA 18-item food security questionnaire | A total of 30.6% of patients were food-secure; 35.5% were insecure without hunger; 24.2%, insecure with mild hunger; and 9.7%, insecure with severe insecurity. |

| Leong, R. et al., 2023 [21] and Leong, R. et al., 2024 [24] | Canada | To evaluate the prevalence of FNI in patients with CD and to examine the relationship between FNI and GFD adherence, quality of life, and various gastrointestinal symptoms. | Cross-sectional | 204 (adults) | - | - | Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) | FI was identified in 17% of CD patients, and 3% were severely FI. FNI is a frequent problem in patients with CD, and it has a significant negative impact on adherence to treatment, symptom control, and quality of life. |

| Siminiuc, R., Turcanu, D., 2022 [28] | Republic of Moldova | To assess the level of care for people with celiac disease in the Republic of Moldova; in terms of public policies, to ensure a sustainable sector that effectively satisfies the food security of people with disorders associated with gluten consumption. | Cross-sectional | - | - | - | An algorithm was utilized, regarding global public policies in support of CD people | The Republic of Moldova does not have adequate policy support to ensure food security for people with gluten-related disorders, which poses major challenges and, as a result, may increase the complications of these problems. |

| Smeets, S. M. et al., 2024 [25] | Netherlands | To determine the prevalence of FNI among individuals with CD and non-celiac gluten sensitivity in the Netherlands and identify potential associations between food insecurity and diet quality. | Cross-sectional | 548 (adults) | 44.7 (±14.6) | 90.30% | USDA 6-item Short Form of the Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) | The overall prevalence of FNI was 23.2%. FNI participants were often younger, had a lower income and a lower educational level, and were associated with a significantly lower diet quality score compared with FNS participants. FNI participants were significantly more likely to experience difficulty with GF eating and cooking. |

| Wang, X. et al., 2024 [13] | Canada | To determine the prevalence and relevant household-level determinants of GF-FI in a multiethnic cohort of Canadian households with children with CD and the associations among child dietary adherence and changes in dietary quality on the GFD. | Cross-sectional | 498 (children) | Hunger Vital Sign and USDA 6-item Short Form of the Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) | A total of 47% of screened households were positive for GF-FI. The high prevalence of GF-FI in households with children with CD in this multiethnic cohort may negatively impact overall dietary quality and adherence to the GFD. Ongoing evaluation of the GF food environment and other factors influencing accessibility, affordability, and adequacy of the GFD is critical to forming effective policies to address these important issues. |

| Country and Reference | Number of Participants | High FNS (%) | Moderate FNS (%) | Low FNS (%) | Very low FNS (%) | FNS (%) | FNI (%) | FNI Without Hunger (%) | FNI with Mild Hunger (%) | FNI with Intense Hunger (%) | Gluten-free Diet Adherence in FNS (n/Total; %) | Gluten-Free Diet Adherence Among FNI (n/Total; %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunger Vital Sign Screener | ||||||||||||

| US [23] | 378 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 76 * | 24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Canada [13] | 498 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 53 | 47 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 186/287; 91.6 | 101/234; 62.3% |

| Hunger Vital Sign Screener adapted to assess gluten-free food insecurity risk (incorporating “gluten-free food” in each screening question) | ||||||||||||

| US [23] | 378 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 73 * | 27 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| USDA 6-item HFSSM | ||||||||||||

| Netherlands [25] | 548 | N/A | N/A | 12.8 | 10.4 | 76.8 | 23.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Canada [13] | 498 | 50.7 | 16.8 | 17.9 | 14.6 | 50.7 * | 49.3 ** | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| USDA 18-item food security questionnaire | ||||||||||||

| Iran [26] | 62 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 30.6 | 69.4 ** | 35.5 | 24.2 | 9.7 | N/A | N/A |

| US [27] | 200 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 2.7 | 84.1 * | 15.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Canada [21] and [24] | 204 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 83 * | 17 | 5.5 | 8 | 3.5 | 100/170; 58.8% | 8/34; 23.5% |

| FIES-SM | ||||||||||||

| Saudi Arabia [22] | 97 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 38 | 62 | 29 | 22 | 11 | 32/37; 86.4% | 39/60; 65% |

| Jordan [12] | 1162 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4.9 | 95.1 | 3.7 | 12.2 | 79.2 | 4/57; 0.34% | 89/1105; 7.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, C.d.S.; Pratesi, C.B.; Zandonadi, R.P. Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diets: A Path or Barrier to Food (In)Security? Nutrients 2025, 17, 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121956

Ribeiro CdS, Pratesi CB, Zandonadi RP. Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diets: A Path or Barrier to Food (In)Security? Nutrients. 2025; 17(12):1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121956

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Camila dos Santos, Claudia B. Pratesi, and Renata Puppin Zandonadi. 2025. "Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diets: A Path or Barrier to Food (In)Security?" Nutrients 17, no. 12: 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121956

APA StyleRibeiro, C. d. S., Pratesi, C. B., & Zandonadi, R. P. (2025). Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Diets: A Path or Barrier to Food (In)Security? Nutrients, 17(12), 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121956