A Comparative Analysis of Graphic Models for Enhancing Nutrition Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review for Selection of Graphic Models for Analysis

- MyPlate (USA, 2011)—the first nationwide plate model, serving as a reference for later studies.

- Healthy Eating Plate (Harvard, 2012)—a model with proven effectiveness, widely cited in the literature.

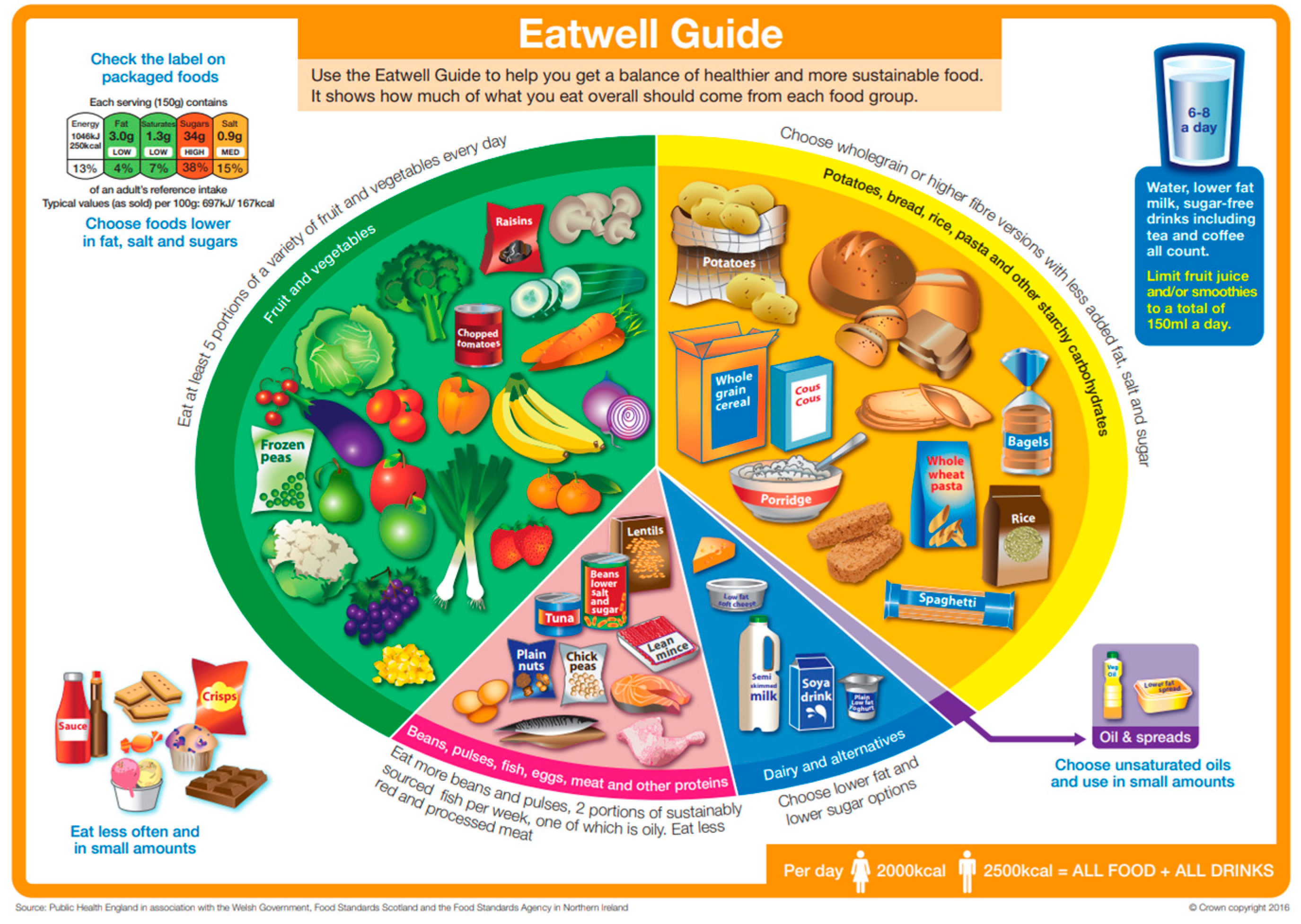

- The UK’s the Eatwell Guide (UK, 2016)—well described in the literature both in terms of structure and has scientific research.

- Malaysian Healthy Plate (Malaysia, 2016)—well described in the literature both in terms of structure and has scientific research.

- Healthy Nutrition Plate (Poland, 2020)—representative of regional guidelines, included due to the timeliness of implementation and lack of comprehensive assessments in the literature.

- Articles and models published in English or Polish.

- Studies evaluating the effectiveness, awareness, or implementation of dietary recommendations in the plate format.

- Data on cultural, economic, or educational barriers to the use of the models.

2.2. Qualitative Analysis of Graphic Models

- -

- A lack of studies on the Polish Healthy Eating Plate.

- -

- A variety of methodologies and measured outcomes in the analyzed literature.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, G.A.; Kim, K.K.; Wilding, J.P.H. World Obesity Federation Obesity: A Chronic Relapsing Progressive Disease Process. A Position Statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2017, 18, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayoral, L.P.-C.; Andrade, G.M.; Mayoral, E.P.-C.; Huerta, T.H.; Canseco, S.P.; Rodal Canales, F.J.; Cabrera-Fuentes, H.A.; Cruz, M.M.; Pérez Santiago, A.D.; Alpuche, J.J.; et al. Obesity Subtypes, Related Biomarkers & Heterogeneity. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 151, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supreme Audit Office Information on the Results of the Audit. In Prevention and Treatment of Obesity in Adults; Rzeszow, Poland, 2024; p. 87. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/plik/id,28874,vp,31705.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Ostrowska, L.; Bogdański, P.; Mamcarz, A. Otyłość i Jej Powikłania; PZWL: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-200-6471-1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Europe: Source Documents. Available online: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/health-promotion-knowledge-gateway/food-based-dietary-guidelines-europe-source-documents-food_en (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Chrisman, M.; Diaz Rios, L.K. Evaluating MyPlate After 8 Years: A Perspective. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Centre of Nutritional Education Talerz Zdrowego Żywienia. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/talerz-zdrowego-zywienia/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Jarosz, M. Pyramid of healthy nutrition and physical activity for adults. Natl. Cent. Nutr. Educ. 2018. Available online: https://ncez.pzh.gov.pl/abc-zywienia/zasady-zdrowego-zywienia/piramida-zdrowego-zywienia-i-aktywnosci-fizycznej-dla-osob-doroslych-2/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- National Centre of Nutritional Education Healthy Eating Plate—Healthy Eating Recommendations and 3 Steps to Health! 2021. Available online: https://odieciewgabinecie.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/dlm_uploads/2024/08/Talerz-Zdrowego-Zywienia-Zalecenia-eng.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Schwartz, J.L.; Vernarelli, J.A. Assessing the Public’s Comprehension of Dietary Guidelines: Use of MyPyramid or MyPlate Is Associated with Healthier Diets among US Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmi, A.; Tseng, M.; Robinson, D.; Neill, D.; Walker, J. A Nutrition Education Intervention Using NOVA Is More Effective Than MyPlate Alone: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard University Healthy Eating Plate. Available online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/healthy-eating-plate (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- The Eatwell Guide. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-eatwell-guide (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Dicken, S.; Makaronidis, J.; van Tulleken, C.; Jassil, F.C.; Hall, K.; Brown, A.C.; Gandini Wheeler-Kingshott, C.A.M.; Fisher, A.; Batterham, R. UPDATE Trial: Investigating the Effects of Ultra-Processed versus Minimally Processed Diets Following UK Dietary Guidance on Health Outcomes: A Protocol for an 8-Week Community-Based Cross-over Randomised Controlled Trial in People with Overweight or Obesity, Followed by a 6-Month Behavioural Intervention. BMJ Open 2024, 14, e079027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture MyPlate. Available online: https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/what-is-myplate (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Harvard University. Healthy Eating Plate—The Nutrition Source 2012. Available online: https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/healthy-eating-plate/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). Malaysian Dietary Guidelines 2020. Available online: https://hq.moh.gov.my/nutrition/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/latest-01.Buku-MDG-2020_12Mac2024.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Jahns, L.; Conrad, Z.; Johnson, L.K.; Raatz, S.K.; Kranz, S. Recognition of Federal Dietary Guidance Icons Is Associated with Greater Diet Quality. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 2120–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakerkish, M.; Shahmoradi, S.; Haidari, F.; Latifi, S.M.; Mohammadshahi, M. The Effect of Nutrition Education Using MyPlate on Lipid Profiles, Glycemic Indices, and Inflammatory Markers in Diabetic Patients. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2022, 11, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, W.J.; Rico, M.; Chandler, M.; Herman, D.R.; Chang, C.; Belin, T.R.; Love, S.; Ramirez, E.; Gelberg, L. Randomized Comparative Effectiveness Trial of 2 Federally Recommended Strategies to Reduce Excess Body Fat in Overweight, Low-Income Patients: MyPlate.Gov vs Calorie Counting. Ann. Fam. Med. 2023, 21, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, S.; Griffiths, A.; Jennings, A.; Malcomson, F.C.; Matu, J.; Minihane, A.-M.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; Ritchie, C.W.; Parra-Soto, S.; Stevenson, E.; et al. Adherence to the Eatwell Guide and Cardiometabolic, Cognitive and Neuroimaging Parameters: An Analysis from the PREVENT Dementia Study. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, O.M.; Townsend, R.; Malcomson, F.C.; Matu, J.; Griffiths, A.; Jennings, A.; Ward, N.; Papier, K.; Best, N.; French, C.; et al. Adherence to the Eatwell Guide and Population and Planetary Health: A Rank Prize Forum Report. Nutr. Bull. 2024, 49, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheelbeek, P.; Green, R.; Papier, K.; Knuppel, A.; Alae-Carew, C.; Balkwill, A.; Key, T.J.; Beral, V.; Dangour, A.D. Health Impacts and Environmental Footprints of Diets That Meet the Eatwell Guide Recommendations: Analyses of Multiple UK Studies. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadnes, L.T.; Celis-Morales, C.; Økland, J.-M.; Parra-Soto, S.; Livingstone, K.M.; Ho, F.K.; Pell, J.P.; Balakrishna, R.; Javadi Arjmand, E.; Johansson, K.A.; et al. Life Expectancy Can Increase by up to 10 Years Following Sustained Shifts towards Healthier Diets in the United Kingdom. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, K.E.; Gaiser, J.; Soucy, A.; Waring, M.E. Awareness and Use of MyPlate Among US Adults With Young Children. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2024, 56, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, M.; Roth, S.E.; Gill, M.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Rice, L.N.; Crespi, C.M.; Prelip, M.L. Exploring the Relationship Between MyPlate Knowledge, Perceived Diet Quality, and Healthy Eating Behaviors Among Adolescents. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2020, 34, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Hasnan, A.; Norsyamlina, C.A.R.; Cheong, S.M.; Ruhaya, S.; Munawara, P.; Wan Shakira, R.H.; Shubash, S.G.; Khairul Hasnan, A. Noor Ani AEver-Never Heard of “Malaysian Healthy Plate”: How Many People Know and Practice This Healthy Eating Concept? PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bisher, M.M.; Al-Otaibi, H.H. Is Adherence to the Saudi Healthy Plate Dietary Guidelines Associated with Eating Concerns Symptoms among Saudi Young Females? Nutrients 2024, 16, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinderknecht, K.L.; The, N.S.; Slining, M.M. Whose Plate Is It? Awareness of MyPlate Among US Adults Over Time Since Implementation. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambogo, E.; Ansai, N.; Wang, C.-Y.; Terry, A.; Fryar, C.D.; Ahluwalia, N.; Ogden, C.L. Awareness of the MyPlate Plan: United States, 2017–March 2020. Natl. Health Stat. Rep. 2022, 178, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wansink, B.; Kranz, S. Who’s Using MyPlate? J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcan, C.; Friend, S.; Flattum, C.F.; Story, M.; Fulkerson, J.A. Fill “Half Your Child’s Plate with Fruits and Vegetables”: Correlations with Food-Related Practices and the Home Food Environment. Appetite 2019, 133, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Wilson, M.J.; Carswell, J.; Okpara, N.; Aydin, H.; Bailey, S.; Davey, M.; Hutto, B.; Wilcox, S.; Friedman, D.B.; et al. A 12-Week Randomized Intervention Comparing the Healthy US, Mediterranean, and Vegetarian Dietary Patterns of the US Dietary Guidelines for Changes in Body Weight, Hemoglobin A1c, Blood Pressure, and Dietary Quality among African American Adults. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, N.; Flannery, O. Association between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and the Eatwell Guide and Changes in Weight and Waist Circumference in Post-Menopausal Women in the UK Women’s Cohort Study. Post Reprod. Health 2023, 29, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, V.; Sklyar, L.; Caldwell, J.I.; Shah, D.; Prudencio, J.M.; Kuo, T. MyPlate and Urban Low-Income Asian Americans in the United States: A Study to Improve Nutrition Education. J. Public Health Policy 2022, 43, 621–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagaruki, G.B.; Mahande, M.J.; Kreppel, K.S.; Mbata, D.; Kilale, A.M.; Shayo, E.H.; Mfinanga, S.G.; Bonfoh, B. Barriers to the Implementation, Uptake and Scaling up of the Healthy Plate Model among Regular Street Food Consumers: A Qualitative Inquiry in Dar-Es-Salaam City, Tanzania. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastert, M.; Chrisman, M.; Endsley, P.; Skarbek, A.; Marchello, N. Familiarity and Use of MyPlate: An Online Focus Group Exploration Among Midwestern K-12 Teachers. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Wansink, A. MyPlate, Half-Plate, and No Plate: How Visual Plate-Related Dietary Benchmarks Influence What Food People Serve. Cureus 2022, 14, e25231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parts of Model | MyPlate | Harvard Healthy Eating Plate | The Eatwell Guide | Malaysian Healthy Plate | Polish Healthy Eating Plate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables and fruits | Vegetables and fruits take up a total of 1/2 the volume of the plate. | Vegetables and fruits take up a total of 1/2 the volume of the plate. | Vegetables and fruits take up over 1/3 the volume of the plate. | Vegetables and fruits take up a total of 1/2 the volume of the plate. | Vegetables and fruits take up a total of 1/2 the volume of the plate. |

| There is a clear division within this group, i.e., about 60% vegetables and 40% fruits. | There is a clear division within this group, i.e., about 70% vegetables and 30% fruits. | There is no clear division within this group; however, there are more vegetables than fruits. | There is no clear division within this group, but about 60% of volume is taken up by vegetables and 40% by fruits. | There is no clear division within this group. | |

| Vegetables should be varied and fruits should be colorful; potatoes and French fries are not included in this group. | It is recommended to eat at least five portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day. | There should be more vegetables than fruits, and they should be of different colors. | |||

| Starchy carbohydrates | Cereals occupy 30% of the plate volume. | Cereals occupy 25% of the volume of the plate. | Potatoes, bread, pasta, or other starchy carbohydrates occupy around 35% of the volume of the plate. | Rice, other cereals, whole grain cereal-based products and Tubers occupy 25% of the volume of the plate | Cereals occupy 25% of the volume of the plate. |

| Half of the cereal products consumed should be whole grains. | All grain products should be whole grains, preferably a variety. | Grain products should be higher-fiber versions or wholegrain, and potatoes should be eaten with skin. | All grain products should be whole grains. | ||

| Protein products | Protein products take up 20% of the volume of the plate. | Protein products take up 25% of the volume of the plate. | Protein products take up approximately 25% of the volume of the plate (15% beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat, and other protein foods, and 10% dairy or dairy alternatives). | Fish, poultry, eggs, meat, and legume take up 25% of the volume of the plate. | Protein products take up 25% of the volume of the plate. |

| They should be diverse. | Fish, poultry, beans, and nuts are most recommended; red meat and cheese should be limited, and bacon and cold cuts avoided. | Choosing lean cuts of meat and mince is recommended; red and processed meat should be limited; and lower-fat and lower-sugar dairy products are recommended. Fish should be eaten twice per week, of which at least one portion should be oily fish. | Poultry, fish, eggs, milk and dairy products, pulses, and nuts are the most recommended; it is recommended to limit red meat and processed meat products. | ||

| Fats | They have not been taken into account. | A bottle of oil is next to the plate. | Fats take up approximately 5% of the volume of the plate. Unsaturated fats like vegetable, rapeseed, olive, and sunflower oils are recommended. | They have not been taken into account. | A bottle of oil is next to the plate, along with a spoon used to measure portions of fat. |

| Moderate fat intake is recommended; the recommended fats are olive oil and canola oil, while butter should be limited and trans fats avoided. | A small addition of fat to the meal is recommended; it is advisable to replace animal fats with vegetable fats (oils, e.g., canola, olive oil). | ||||

| Beverages | Drinking milk or dairy products with each meal is recommended. | Next to the plate is a glass of water. It is recommended to drink water, tea, or coffee (with little or no sugar); to limit the consumption of milk and dairy products to 1–2 servings per day and juices to one small glass per day; and to avoid sweetened beverages. | Next to the plate is a glass of water. It is recommended to drink water; lower-fat milk; and sugar-free drinks, including tea and coffee, and to limit the consumption of juices and/or smoothies to a total of 150 mL a day. | They have not been taken into account. | Some examples of recommended beverages (water, tea, and coffee) are next to the plate. |

| Other | No | No | A group of sweets and salty snacks is next to the plate, with a recommendation to eat them less often and in small amounts. An example of a label is next to the plate, with a recommendation to check labels on packaged foods and to choose foods lower in fat, salt, and sugars. Information on recommended daily energy intake for females (2000 kcal) and males (2500 kcal) from all foods and all drinks is at the bottom. | No | A crossed-out salt shaker is next to the plate. A crossed-out group of sweets and salty snacks is next to the plate. |

| Physical activity recommendation | No | The graphic is complemented by the recommendation “Stay active!’’. | No | No | The graphic is complemented by the recommendation “Be physically active, keep body weight normal”. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jodkiewicz, M.; Malinowska, J.; Marek-Woźny, K. A Comparative Analysis of Graphic Models for Enhancing Nutrition Education. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121947

Jodkiewicz M, Malinowska J, Marek-Woźny K. A Comparative Analysis of Graphic Models for Enhancing Nutrition Education. Nutrients. 2025; 17(12):1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121947

Chicago/Turabian StyleJodkiewicz, Magdalena, Justyna Malinowska, and Karolina Marek-Woźny. 2025. "A Comparative Analysis of Graphic Models for Enhancing Nutrition Education" Nutrients 17, no. 12: 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121947

APA StyleJodkiewicz, M., Malinowska, J., & Marek-Woźny, K. (2025). A Comparative Analysis of Graphic Models for Enhancing Nutrition Education. Nutrients, 17(12), 1947. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17121947