Home and Wild Food Procurement Were Associated with Greater Intake of Fruits and Vegetables During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern New England in a Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Development and Sampling Strategy

2.2. Variables for Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

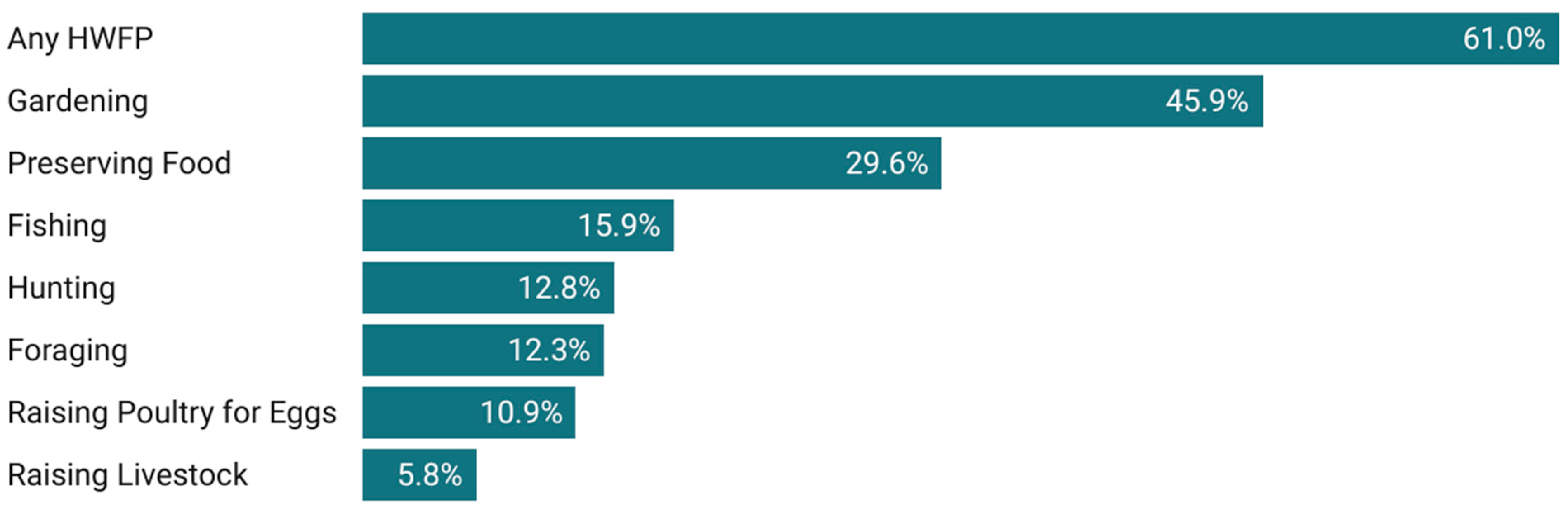

3.1. HWFP Engagement and Food Security Status

3.2. HWFP Engagement and Fruit and Vegetable Intake

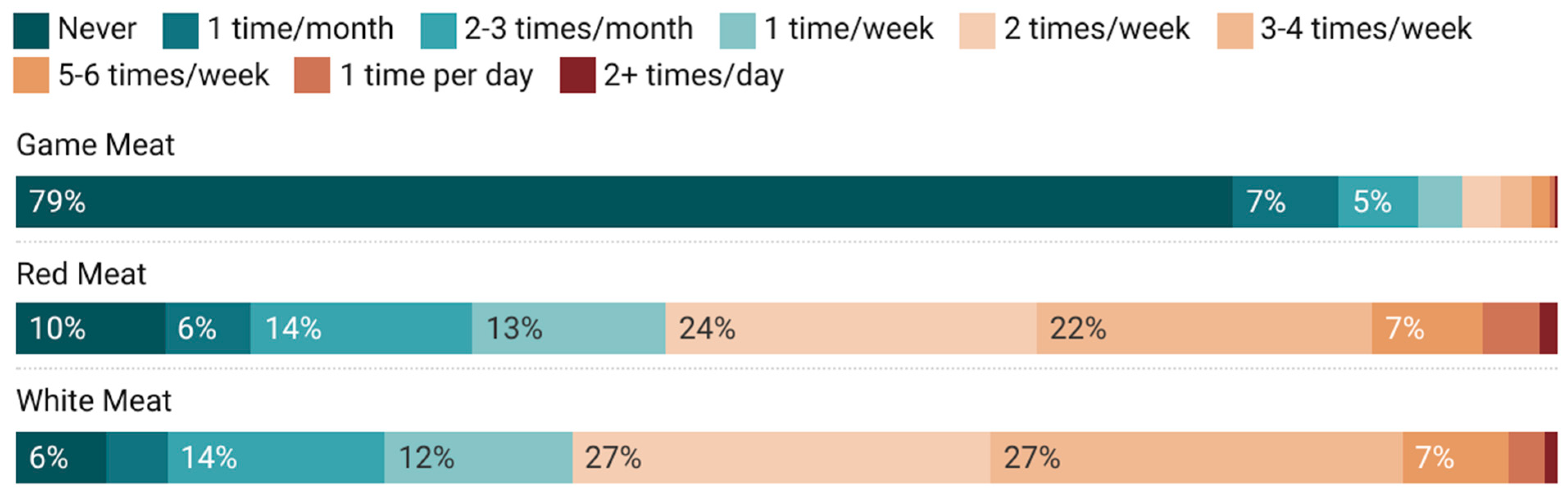

3.3. Hunting and Meat Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HWFP | Home and wild food procurement |

| DSQ | Dietary Screener Questionnaire |

| DGA | Dietary Guidelines for Americans |

References

- Danks, Z.D.; Schiavone, M.V.; Butler, A.B.; Fricke, K.; Davis, A.; Cobb, D.T. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on 2020 spring turkey hunting across the United States. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2022, 46, e1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, A.; Beardmore, B.; Gerrish, G.A.; Sass, G.G.; Jensen, O.P. Social fish-tancing in wisconsin: The effects of the covid-19 pandemic on statewide license sales and fishing effort in northern inland lakes. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2022, 42, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midway, S.R.; Lynch, A.J.; Peoples, B.K.; Dance, M.; Caffey, R. COVID-19 influences on US recreational angler behavior. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, D. Suppliers Field Growing Demand for Seeds from Pandemic Gardeners; NPR: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cattivelli, V. Review and analysis of the motivations associated with urban gardening in the pandemic period. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittman, H. Food sovereignty: An inclusive model for feeding the world and cooling the planet. One Earth 2023, 6, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. UN FAO World Food Summit: Plan of Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hadley, C.; Crooks, D.L. Coping and the biosocial consequences of food insecurity in the 21st century. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2012, 149, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.K.; Shultz, J.A.; Edlefsen, M.; Butkus, S.N. Food coping strategies used by food pantry clients at different levels of household food security status. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2007, 1, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, M.T.; Wirkkala, K.B.; Belarmino, E.H.; Bertmann, F. Home food procurement impacts food security and diet quality during COVID-19. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, M.T.; McCarthy, A.C.; Malacarne, J.; Bliss, S.; Belarmino, E.H.; Laurent, J.; Merrill, S.C.; Nowak, S.A.; Schattman, R.E. Home and wild food procurement were associated with improved food security during the COVID-19 pandemic in two rural US states. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.T.; Ribeiro, S.M.; Germani, A.C.C.G.; Bógus, C.M. The impact of urban gardens on adequate and healthy food: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney, P.A.; Hamada, J.L.; Rdesinski, R.; Sprager, L.; Nichols, K.R.; Liu, B.Y.; Pelayo, J.; Sanchez, M.A.; Shannon, J. Impact of a community gardening project on vegetable intake, food security and family relationships: A community-based participatory research study. J. Community Health 2012, 37, 874–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beavers, A.W.; Atkinson, A.; Alaimo, K. How gardening and a gardener support program in detroit influence participants’ diet, food security, and food values. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortright, R.; Wakefield, S. Edible backyards: A qualitative study of household food growing and its contributions to food security. Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algert, S.; Diekmann, L.; Renvall, M.; Gray, L. Community and home gardens increase vegetable intake and food security of residents in San Jose, California. Calif. Agric. 2016, 70, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, K.; Packnett, E.; Miles, R.A.; Kruger, D.J. Fruit and vegetable intake among urban community gardeners. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2008, 40, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, J.S.; Soobader, M.-J.; Turbin, M.S.; Hale, J.W.; Buchenau, M.; Marshall, J.A. The Influence of Social Involvement, Neighborhood Aesthetics, and Community Garden Participation on Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Am. J. Public. Health. 2011, 101, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, K.; Beavers, A.W.; Coringrato, E.; Lacy, K.; Ma, W.; Hurley, T.G.; Hébert, J.R. Community gardening increases vegetable intake and seasonal eating from baseline to harvest: Results from a mixed methods randomized controlled trial. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.Y.; Thompson, B.A.; Werner, M.; Malecki, K.; Imm, P.; Anderson, H.A. Levels of nutrients in relation to fish consumption among older male anglers in Wisconsin. Environ. Res. 2015, 142, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, C.; Shatenstein, B.; Paradis, G.; Kosatsky, T. Absence of cardiovascular benefits and sportfish consumption among St. Lawrence River anglers. Environ. Res. 2003, 93, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.R.; Meilby, H.; Smith-Hall, C.; Pouliot, M.; Treue, T. The importance of wild meat in the global south. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 146, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann-Uschner, K.; Kraehnert, K. Food intake and the role of food self-provisioning. J. Dev. Stud. 2017, 53, 1303–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atapattu, M.; Saranga, K.; Abeywickrama, L.; Gunawardana, W.; Munasinghe, M. Contribution of backyard chicken egg production to fulfill household nutrient requirement: A study in southern Sri Lanka. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, V.O.; Hendriks, A.M.; Ruiter, R.A.C.; Kremers, S.P.J. Determinants of dietary behavior and physical activity among Canadian Inuit: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, M.; Hagar, H.; Zivot, C.; Dodd, W.; Skinner, K.; Kenny, T.-A.; Caughey, A.; Gaupholm, J.; Lemire, M. Drivers and health implications of the dietary transition among Inuit in the Canadian Arctic: A scoping review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2650–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.B.; Xu, X.; Toth, J.F., Jr. Lifestyle options and economic strategies: Subsistence activities in the mississippi delta. Rural Sociol. 2011, 63, 599–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, S.; Beckley, T.M. Hunted, harvested and homegrown: The prevalence of self-provisioning in rural Canada. J. Rural Community Dev. 2006, 1, 114–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kamiyama, C.; Hori, K.; Matsui, T.; Pretty, J.; Saito, O. Longitudinal analysis of home food production and food sharing behavior in Japan: Multiple benefits of local food systems and the recent impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 2277–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkkala, K.B.; Niles, M.T.; Belarmino, E.H.; Bertmann, F. The fruits of labor: Home food procurement and mental health in the time of COVID-19. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2023, 18, 450–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, M.T.; Neff, R.A.; Biehl, E.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Acciai, F.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P. Food Access and Food Security During COVID-19 Survey—Version 2.1. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1881146592845264000 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Niles, M.T.; Neff, R.A.; Biehl, E.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Acciai, F.; Ohri-Vachaspati, P.; Josephson, A.; Harper, K.; Robinson, J. Food Access and Food Security During COVID-19 Survey—Version 3.0. Available online: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/BIHEYJ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- U.S. Census Bureau Data Profiles. American Community Survey. Available online: https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- USDA Economic Research Service. U.S. Household Food Security Module: Six-Item Short Form; USDA Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, F.E.; Midthune, D.; Kahle, L.; Dodd, K.W. Development and evaluation of the national cancer institute’s dietary screener questionnaire scoring algorithms. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute Data Processing&Scoring Procedures Using Current Methods. Dietary Screener in the NHANES 2009-10. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/scoring/current/ (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- USDA Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes; USDA Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- University of Washington Rural Health Research Center RUCA Maps. Available online: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-maps.php (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Stata Statistical Software, Release 17; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025, 9th ed.; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, L.; Guzman, P.; Glowa, K.M.; Drevno, A.G. Can home gardens scale up into movements for social change? The role of home gardens in providing food security and community change in San Jose, California. Local Environ. 2014, 19, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.W.; Epel, E.S.; Ritchie, L.D.; Crawford, P.B.; Laraia, B.A. Food insecurity is inversely associated with diet quality of lower-income adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1943–1953.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, K.L.; Connor, L.M. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.A.; Spees, C.K.; Markwordt, A.M.; Watowicz, R.P.; Clark, J.K.; Hooker, N.H. Differences in us adult dietary patterns by food security status. J. Consum. Aff. 2017, 51, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertmann, F.; Rogomentich, K.; Belarmino, E.H.; Niles, M.T. The food bank and food pantries help food insecure participants maintain fruit and vegetable intake during COVID-19. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 673158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, M.M.; Beavers, A.W. The relationship between food security status and fruit and vegetable intake during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Miguel, E.; Lopes, S.O.; Araújo, S.P.; Priore, S.E.; de Cássia Gonçalves Alfenas, R.; Hermsdorff, H.H.M. Association between food insecurity and cardiometabolic risk in adults and the elderly: A systematic review. J. Glob. Health 2020, 10, 020402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.K.; Lammert, L.J.; Beverly, E.A. Food insecurity and its impact on body weight, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and mental health. Curr. Cardiovasc. Risk. Rep. 2021, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaway, J.D.; Afshin, A.; Ashbaugh, C.; Bisignano, C.; Brauer, M.; Ferrara, G.; Garcia, V.; Haile, D.; Hay, S.I.; He, J.; et al. Health effects associated with vegetable consumption: A Burden of Proof study. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2066–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Agricultural Research Service FoodData Central. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Linville, T.; Hanson, K.L.; Sobal, J. Hunting and raising livestock are associated with meat-related attitudes, norms and frequent consumption: Implications for dietary guidance to rural residents. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 3067–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle, A.; McCarthy, A.C.; Niles, M.T. Home Food Production Before, During and Since Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern New England; College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Faculty Publications; University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Variable Name | Question(s) | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Food Security Status | USDA 6-item food security model for past 12 months | 0 = Food Secure; 1 = Food Insecure |

| Dietary Quality Variables | ||

| Fruit and Vegetable Intake | Predicted intake of fruits and vegetables including legumes and excluding French fries based on DSQ | Original DSQ scale: 1 = Never; 2 = 1 time in the last month; 3 = 2–3 times in the last month; 4 = 1 time per week; 5 = 2 times per week; 6 = 3–4 times per week; 7 = 5–6 times per week; 8 = 1 time per day; 9 = 2 or more times per day |

| Fruit Intake | Predicted intake of fruits (including 100% pure fruit juice) based on DSQ | |

| Vegetable Intake | Predicted intake of vegetables excluding French fries based on DSQ | Estimated intake reported in Cup Equivalents Per Day calculated using the scoring algorithms developed by the National Cancer Institute. |

| Game Meat Consumption | During the past month, how often did you eat wild game meat such as venison, wild turkey, pheasant, or bear? | 0 = Did Not Consume; 1 = Did Consume |

| Red Meat Consumption | During the past month, how often did you eat red meat, such as beef, pork, ham, or sausage? | 1 = Never; 2 = 1 time in the last month; 3 = 2–3 times in the last month; 4 = 1 time per week; 5 = 2 times per week; 6 = 3–4 times per week; 7 = 5–6 times per week; 8 = 1 time per day; 9 = 2 or more times per day |

| White Meat Consumption | During the past month, how often did you eat white meat, such as chicken and turkey? | |

| Home and Wild Food Procurement (HWFP) Variables | ||

| Gardening | Has your household engaged in any of these activities in the last 12 months? | 0 = No; 1 = Yes |

| Foraging | ||

| Fishing | ||

| Hunting | ||

| Raising Livestock | ||

| Raising Poultry for Eggs | ||

| Preserving Food | ||

| Any HWFP | Variable created based on respondent indicating that they engaged in any of the individual HWFP activities | 0 = No; 1 = Yes |

| Demographic Variables | ||

| Annual Household Income | Which of the following best describes your household income range before taxes? [2021 survey asked about 2019 income; 2022 survey asked about 2021 income] | 0 = Household income < $50,000 1 = Household income ≥ $50,000 |

| College Degree | What is the highest level of formal education that you have completed? | 0 = Less than associate’s degree 1 = Associate’s or higher |

| Age | In what year were you born? | 0 = Under 65; 1 = 65 and older |

| Race | What is your race? Check all that apply. | Response options include: American Indian/Alaska Native; Asian Indian; Black or African American; Chamorro; Chinese; Filipino; Japanese; Korean; Native Hawaiian; Samoan; Vietnamese; White |

| Ethnicity | Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin? | 1 = No, not Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin; 2 = Yes, Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano; 3 = Yes, Puerto Rican; 4 = Yes, Cuban; 5 = Yes, Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin |

| Race/Ethnicity Binary | Based on responses to race and ethnicity questions above | 0 = BIPOC; 1 = non-Hispanic White |

| Gender Identity | Which of the following best describes your gender identity? | 0 = Male; 1 = Female; 2 = Another Gender Identity |

| Rural/urban classification | Rural or urban classification based on zip code responses and RUCA codes | 0 = Rural; 1 = Urban |

| Job Disruption | Have you or anyone in your household experienced a loss of income, reduction of hours, furlough or job loss since the COVID-19 outbreak began 11 March 2020? | 0 = No; 1 = Yes |

| Category | Characteristic | Sample | Population 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | % | ||

| Age | 18–29 | 360 | 18.0 | 18.1 |

| 30–44 | 578 | 28.9 | 21.7 | |

| 45–64 | 638 | 31.9 | 35.3 | |

| ≥65 | 425 | 21.2 | 25.0 | |

| Gender | Male | 657 | 32.8 | 49.4 |

| Female | 1308 | 65.4 | 50.6 | |

| Other Gender | 28 | 1.4 | n/a | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 1827 | 91.3 | 93.1 |

| BIPOC | 157 | 7.9 | 6.9 | |

| Education Level | No College Degree | 1052 | 52.6 | 54.4 |

| College Degree | 949 | 47.4 | 45.6 | |

| Household Income | <USD50,000/year | 973 | 48.6 | 38.8 |

| ≥USD50,000/year | 1027 | 51.3 | 61.2 | |

| Rurality | Urban | 853 | 42.7 | 46.5 |

| Rural | 1143 | 57.1 | 53.5 | |

| Job Disruption | Yes | 1230 | 61.5 | n/a |

| No | 770 | 38.5 | n/a | |

| Activity | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | Accuracy Rate (%) 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any HWFP | 1.19 | 0.141 | 0.132 | 0.948 | 1.504 | 73.3 |

| Gardening | 1.06 | 0.123 | 0.606 | 0.846 | 1.331 | 73.2 |

| Preserving Food | 1.22 | 0.159 | 0.128 | 0.945 | 1.574 | 73.3 |

| Foraging | 1.61 | 0.275 | 0.006 | 1.149 | 2.248 | 73.7 |

| Hunting | 1.64 | 0.277 | 0.003 | 1.177 | 2.283 | 73.4 |

| Fishing | 1.60 | 0.264 | 0.005 | 1.156 | 2.208 | 73.2 |

| Raising Livestock | 2.71 | 0.733 | 0.000 | 1.592 | 4.602 | 73.9 |

| Raising Poultry for Eggs | 2.07 | 0.390 | 0.000 | 1.433 | 2.997 | 73.9 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gardening | 0.85 | 0.110 | 0.204 | 0.656 | 1.094 |

| Preserving Food | 0.99 | 0.148 | 0.987 | 0.745 | 1.335 |

| Foraging | 1.27 | 0.239 | 0.197 | 0.882 | 1.839 |

| Hunting | 1.08 | 0.217 | 0.716 | 0.725 | 1.599 |

| Fishing | 1.24 | 0.242 | 0.272 | 0.845 | 1.818 |

| Raising Livestock | 1.71 | 0.535 | 0.089 | 0.922 | 3.154 |

| Raising Poultry for Eggs | 1.56 | 0.339 | 0.041 | 1.018 | 2.390 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.75 | 0.154 | 0.156 | 0.497 | 1.118 |

| Gender Identity | 1.08 | 0.136 | 0.536 | 0.845 | 1.383 |

| Age | 0.32 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.228 | 0.438 |

| Education Level | 0.52 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.408 | 0.656 |

| Household Income | 0.25 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.199 | 0.322 |

| Rurality | 1.05 | 0.121 | 0.670 | 0.839 | 1.315 |

| Job Disruption | 3.54 | 0.417 | 0.000 | 2.814 | 4.462 |

| Survey Year | 1.64 | 0.197 | 0.000 | 1.297 | 2.076 |

| HWFP Activity | Diet Factor | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gardening | Vegetable Intake | 0.09 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.130 |

| Fruit Intake | 0.07 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.104 | |

| Fruit and Vegetable Intake | 0.15 | 0.033 | 0.000 | 0.087 | 0.217 | |

| Preserving Food | Vegetable Intake | 0.05 | 0.022 | 0.028 | 0.005 | 0.093 |

| Fruit Intake | 0.05 | 0.021 | 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.093 | |

| Fruit and Vegetable Intake | 0.09 | 0.037 | 0.019 | 0.014 | 0.160 | |

| Foraging | Vegetable Intake | 0.08 | 0.030 | 0.012 | 0.017 | 0.138 |

| Fruit Intake | 0.03 | 0.028 | 0.248 | −0.023 | 0.089 | |

| Fruit and Vegetable Intake | 0.11 | 0.051 | 0.038 | 0.005 | 0.210 | |

| Diet Factor | HWFP Activity | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetable Intake | Gardening | 0.08 | 0.022 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.120 |

| Foraging | 0.04 | 0.034 | 0.190 | −0.022 | 0.059 | |

| Preserving Food | 0.01 | 0.024 | 0.627 | −0.035 | 0.059 | |

| Fruit Intake | Gardening | 0.06 | 0.021 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.099 |

| Foraging | 0.00 | 0.030 | 0.981 | −0.059 | 0.060 | |

| Preserving Food | 0.03 | 0.023 | 0.212 | −0.016 | 0.074 | |

| Fruit and Vegetable Intake | Gardening | 0.14 | 0.037 | 0.000 | 0.064 | 0.207 |

| Foraging | 0.04 | 0.056 | 0.421 | −0.064 | 0.154 | |

| Preserving Food | 0.03 | 0.040 | 0.487 | −0.050 | 0.207 | |

| HWFP Activity | Food Security Status | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any HWFP | Food Secure | 0.08 | 0.043 | 0.074 | −0.017 | 0.150 |

| Food Insecure | 0.14 | 0.050 | 0.005 | 0.113 | 0.327 | |

| Gardening | Food Secure | 0.12 | 0.043 | 0.006 | 0.035 | 0.200 |

| Food Insecure | 0.22 | 0.054 | 0.000 | 0.100 | 0.327 | |

| Preservation | Food Secure | 0.10 | 0.048 | 0.050 | 0.000 | 0.192 |

| Food Insecure | 0.07 | 0.060 | 0.245 | −0.048 | 0.188 | |

| Foraging | Food Secure | 0.18 | 0.069 | 0.009 | 0.045 | 0.320 |

| Food Insecure | 0.02 | 0.079 | 0.851 | −0.142 | 0.172 | |

| Fruit and Vegetable Intake | Coefficient | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Secure | |||||

| Gardening | 0.087 | 0.047 | 0.065 | −0.006 | 0.179 |

| Preserving Food | 0.043 | 0.052 | 0.412 | −0.059 | 0.145 |

| Foraging | 0.139 | 0.076 | 0.069 | −0.011 | 0.288 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −0.115 | 0.083 | 0.166 | −0.278 | 0.048 |

| Gender Identity | −0.213 | 0.046 | 0.000 | −0.304 | −0.123 |

| Age | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.303 | −0.045 | 0.143 |

| Education Level | 0.057 | 0.045 | 0.206 | −0.031 | 0.145 |

| Household Income | 0.176 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.091 | 0.261 |

| Rurality | −0.053 | 0.043 | 0.220 | −0.138 | 0.032 |

| Job Disruption | 0.066 | 0.048 | 0.165 | −0.027 | 0.160 |

| Survey Year | 0.113 | 0.044 | 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.199 |

| Food Insecure | |||||

| Gardening | 0.235 | 0.062 | 0.000 | 0.113 | 0.357 |

| Preserving Food | 0.009 | 0.061 | 0.882 | −0.111 | 0.129 |

| Foraging | −0.085 | 0.084 | 0.310 | −0.250 | 0.080 |

| Race/Ethnicity | −0.047 | 0.075 | 0.535 | −0.194 | 0.101 |

| Gender Identity | −0.347 | 0.064 | 0.000 | −0.473 | −0.221 |

| Age | 0.013 | 0.085 | 0.875 | −0.154 | 0.180 |

| Education Level | 0.056 | 0.061 | 0.359 | −0.064 | 0.177 |

| Household Income | 0.078 | 0.058 | 0.178 | −0.036 | 0.191 |

| Rurality | 0.095 | 0.056 | 0.092 | −0.015 | 0.204 |

| Job Disruption | −0.014 | 0.053 | 0.785 | −0.118 | 0.089 |

| Survey Year | −0.101 | 0.056 | 0.072 | −0.212 | 0.009 |

| Dietary Factor | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | Accuracy Rate 1 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Game Meat | 17.25 | 3.050 | 0.000 | 12.193 | 24.390 | 84.1 |

| Red Meat | 1.91 | 0.227 | 0.000 | 1.513 | 2.411 | n/a |

| White Meat | 1.87 | 0.192 | 0.000 | 1.527 | 2.287 | n/a |

| Dietary Factor | Food Security Status | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI | Accuracy Rate 1 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Game Meat | Food Secure | 23.72 | 5.854 | 0.000 | 14.621 | 38.474 | 68.9 |

| Food Insecure | 13.27 | 3.656 | 0.000 | 7.731 | 22.767 | 68.9 | |

| Red Meat | Food Secure | 1.99 | 0.327 | 0.000 | 1.446 | 2.749 | n/a |

| Food Insecure | 2.23 | 0.435 | 0.000 | 1.520 | 3.267 | n/a | |

| White Meat | Food Secure | 1.25 | 0.183 | 0.134 | 0.935 | 1.660 | n/a |

| Food Insecure | 1.75 | 0.354 | 0.006 | 1.177 | 2.602 | n/a | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCarthy, A.C.; Angle, A.; Bliss, S.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Rose, K.; Niles, M.T. Home and Wild Food Procurement Were Associated with Greater Intake of Fruits and Vegetables During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern New England in a Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101627

McCarthy AC, Angle A, Bliss S, Bertmann F, Belarmino EH, Rose K, Niles MT. Home and Wild Food Procurement Were Associated with Greater Intake of Fruits and Vegetables During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern New England in a Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2025; 17(10):1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101627

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCarthy, Ashley C., Ashleigh Angle, Sam Bliss, Farryl Bertmann, Emily H. Belarmino, Kelsey Rose, and Meredith T. Niles. 2025. "Home and Wild Food Procurement Were Associated with Greater Intake of Fruits and Vegetables During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern New England in a Cross-Sectional Study" Nutrients 17, no. 10: 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101627

APA StyleMcCarthy, A. C., Angle, A., Bliss, S., Bertmann, F., Belarmino, E. H., Rose, K., & Niles, M. T. (2025). Home and Wild Food Procurement Were Associated with Greater Intake of Fruits and Vegetables During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Northern New England in a Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients, 17(10), 1627. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101627