Eating Disorder Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis: Relationships Between Neuroticism, Body Dissatisfaction, and Self-Esteem

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Eating Disorder Symptoms and Multiple Sclerosis

1.2. The Role of Neuroticism in Eating Disorders in Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis

1.3. The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Body Dissatisfaction

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

2.2.2. Psychological Variables

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Data Inspection

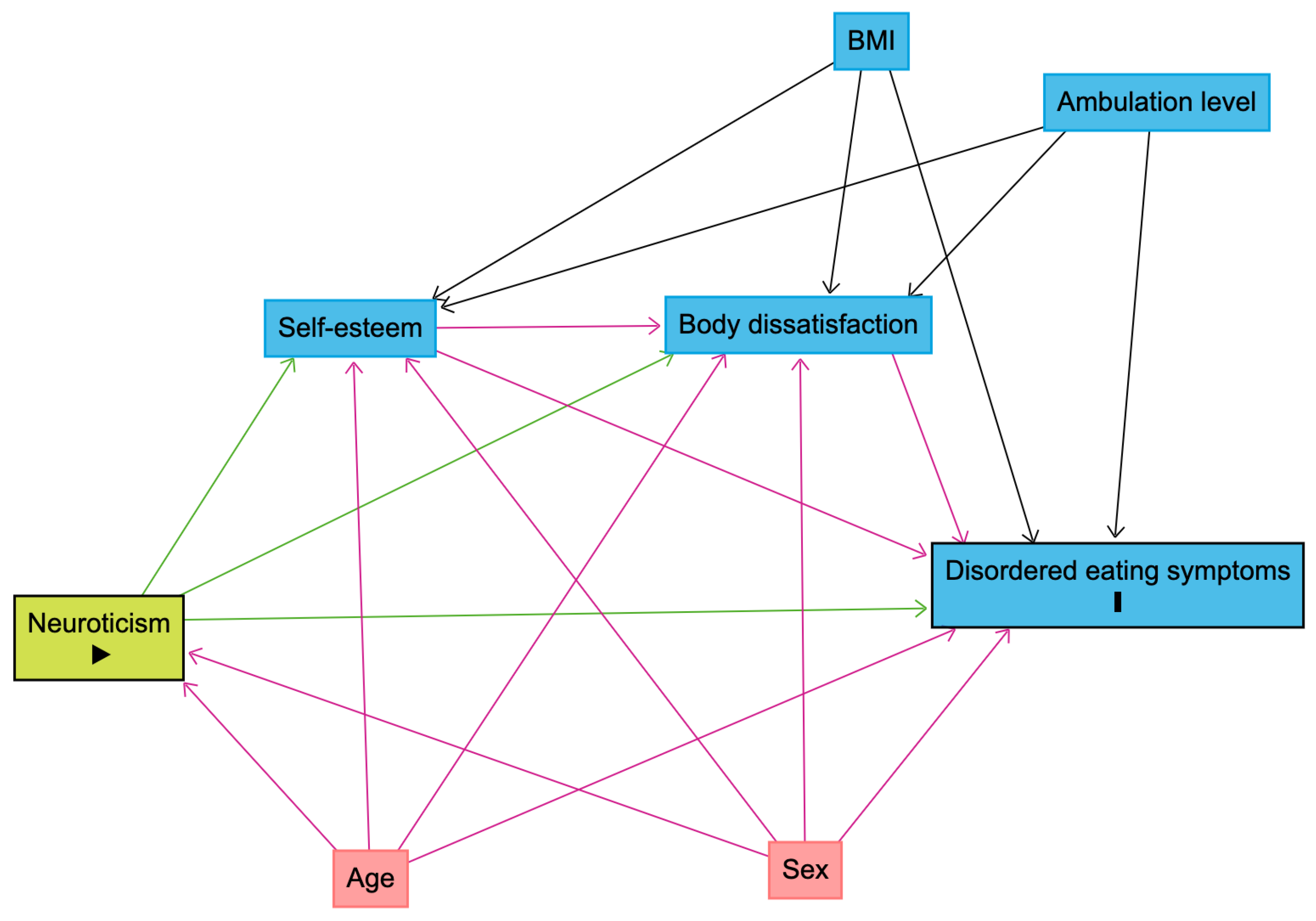

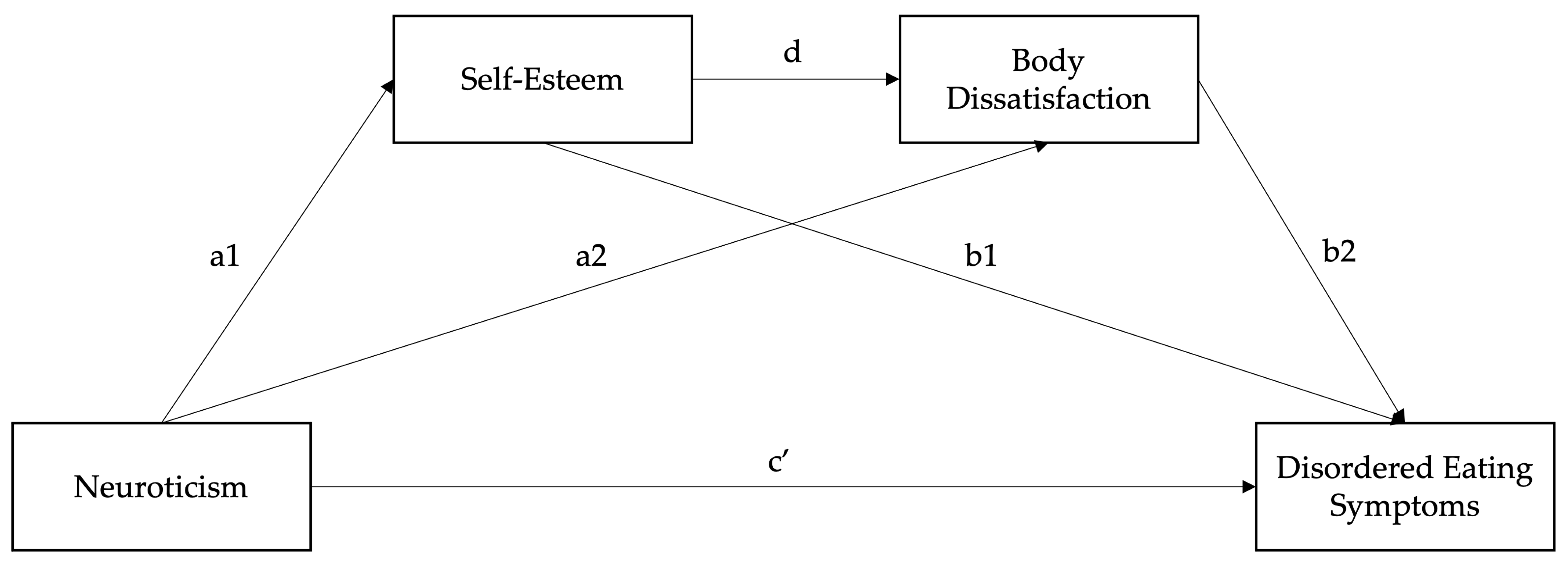

2.3.2. Serial Mediation Model

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

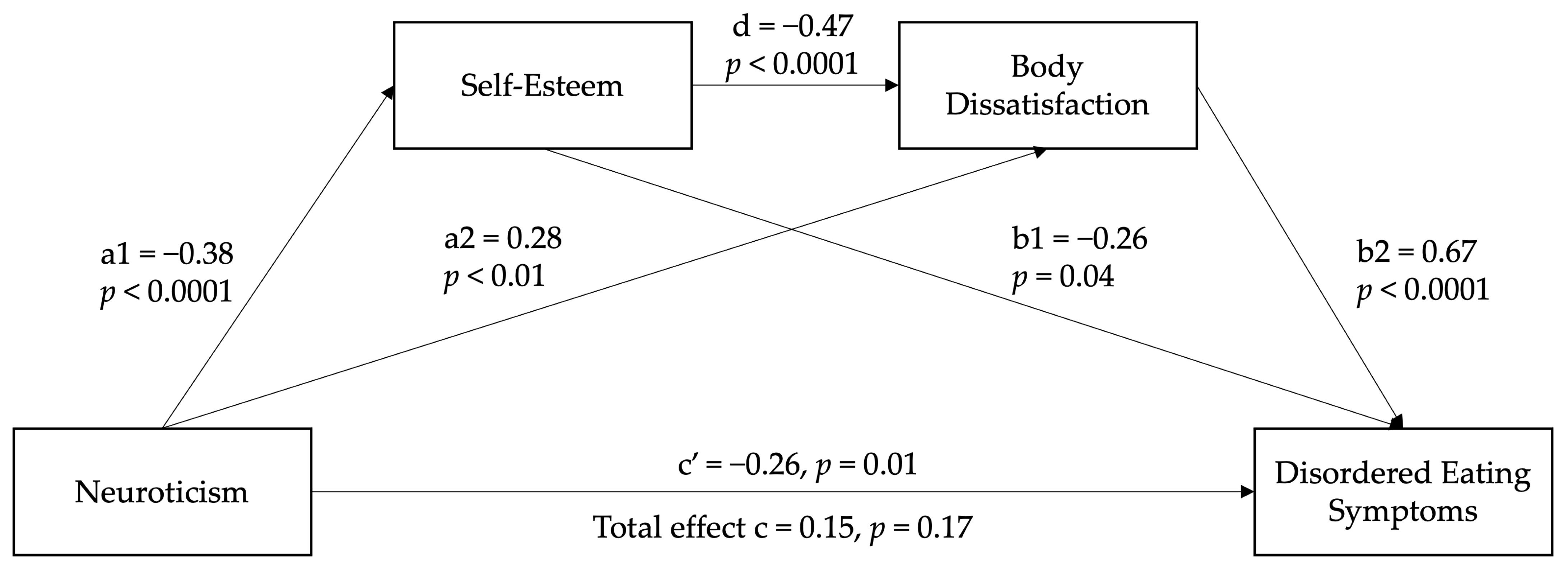

3.3. Serial Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| ED | Eating disorder |

| DE | Disordered eating |

| BFI | Big Five Inventory |

| RSES | Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale |

| BSQ | Body Shape Questionnaire |

| EAT-26 | Eating Attitudes Test |

Appendix A

| Model Pathway | β | SE | z | p | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism → Self-esteem (a1) | −0.42 (−0.46) | 0.06 | −7.17 | <0.001 | −0.54 | −0.31 |

| Neuroticism → Body dissatisfaction (a2) | 0.23 (0.15) | 0.12 | 1.98 | 0.048 | 0.00 | 0.45 |

| Self-esteem → ED symptoms (b1) | −0.27 (−0.14) | 0.13 | −2.00 | 0.046 | −0.53 | −0.01 |

| Body dissatisfaction → ED symptoms (b2) | 0.68 (0.59) | 0.08 | 9.05 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.82 |

| Self-esteem → Body dissatisfaction (d) | −0.44 (−0.27) | 0.13 | −3.36 | 0.001 | −0.70 | −0.18 |

| Total model effect | 0.16 (0.09) | 0.13 | 1.29 | 0.198 | −0.09 | 0.41 |

| Direct effect (c’) | −0.23 (−0.13) | 0.12 | −2.00 | 0.045 | −0.45 | −0.00 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.39 (0.23) | 0.10 | 4.12 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.58 |

| Neuroticism → Self-esteem → ED symptoms (ind1) | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.06 | 1.92 | 0.054 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| Neuroticism → Body dissatisfaction → ED symptoms (ind2) | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.08 | 1.94 | 0.053 | 0.00 | 0.32 |

| Neuroticism → Self-esteem → Body dissatisfaction → ED symptoms (ind3) | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.04 | 2.89 | 0.053 | 0.05 | 0.22 |

| Pairwise comparisons of indirect effects | ||||||

| Ind1–Ind2 | −0.04 (−0.03) | 0.10 | −0.42 | 0.673 | −0.25 | 0.16 |

| Ind1–Ind3 | −0.01 (−0.01) | 0.07 | −0.19 | 0.851 | −0.16 | 0.13 |

| Ind2–Ind3 | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.777 | −0.18 | 0.23 |

References

- Ward, M.; Goldman, M.D. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis. Continuum 2022, 28, 988–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, S.D.; Thompson, N.R.; Sullivan, A.B. Prevalence and correlates of body image dissatisfaction in patients with multiple sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2019, 21, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasofer, D.R.; Attia, E.; Pike, K.M. Eating disorders. In Psychopathology: From Science to Clinical Practice; Castonguay, L.G., Oltmanns, T.F., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 198–240. [Google Scholar]

- Crone, C.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Attia, E.; Boland, R.; Escobar, J.; Fornari, V.; Golden, N.; Guarda, A.; Jackson-Triche, M.; Manzo, L.; et al. The american psychiatric association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2023, 180, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassin, S.E.; von Ranson, K.M. Personality and eating disorders: A decade in review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farstad, S.M.; McGeown, L.M.; von Ranson, K.M. Eating disorders and personality, 2004–2016: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 46, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmartin, T.; Gurvich, C.; Sharp, G. The relationship between disordered eating behaviour and the five factor model personality dimensions: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 78, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Schmidt, L.A.; Vaillancourt, T.; McDougall, P.; Laliberte, M. Neuroticism and introversion: A risky combination for disordered eating among a non-clinical sample of undergraduate women. Eat. Behav. 2006, 7, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Robson, D.A. Personality and body dissatisfaction: An updated systematic review with meta-analysis. Body Image 2020, 33, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Taylor, R.; Carvalho, C. Body dissatisfaction assessed by the photographic figure rating scale is associated with sociocultural, personality, and media influences. Scand. J. Psychol. 2011, 52, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clague, C.A.; Prnjak, K.; Mitchison, D. “I don’t want them to judge me”: Separating out the role of fear of negative evaluation, neuroticism, and low self-esteem in eating disorders. Eat. Behav. 2023, 49, 101708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.; McIntosh, V.V.W.; Britt, E.; Carter, J.D.; Jordan, J.; Bulik, C.M. The effect of temperament and character on body dissatisfaction in women with bulimia nervosa: The role of low self-esteem and depression. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2022, 30, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorek, M.; Song, A.V.; Dunham, Y. Self-esteem as a mediator between personality traits and body esteem: Path analyses across gender and race/ethnicity. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacNeill, L.P.; Best, L.A.; Davis, L.L. The role of personality in body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Discrepancies between men and women. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervera, S.; Lahortiga, F.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Gual, P.; de Irala-Estevez, J.; Alonso, Y. Neuroticism and low self-esteem as risk factors for incident eating disorders in a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 33, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, S.; Dapp, L.C.; Orth, U. The link between low self-esteem and eating disorders: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 11, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An update on the prevalence of eating disorders in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmiche, M.; Dechelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000-2018 period: A systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, L.; Clemente, D.; Heredia, C.; Abasolo, L. Self-esteem, self-concept, and body image of young people with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: A systematic literature review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2024, 68, 152486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Mohamadirizi, M.; Mohamadirizi, S.; Hosseini, S.A. Evaluation of body image in cancer patients and its association with clinical variables. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Borriello, A.; Casaburo, F.; Del Giudice, E.M.; Iafusco, D. Body image problems and disordered eating behaviors in Italian adolescents with and without type 1 diabetes: An examination with a gender-specific body image measure. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 556520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoyne, C.R.; Simpson, S., Jr.; Chen, J.; van der Mei, I.; Marck, C.H. Modifiable factors associated with depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2019, 140, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikula, P.; Timkova, V.; Fedicova, M.; Szilasiova, J.; Nagyova, I. Self-management, self-esteem and their associations with psychological well-being in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 53, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiropoulos, L.A.; Kilpatrick, T.; Holmes, A.; Threader, J. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a tailored cognitive behavioural therapy based intervention for depressive symptoms in those newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reininghaus, E.; Reininghaus, B.; Fitz, W.; Hecht, K.; Bonelli, R.M. Sexual behavior, body image, and partnership in chronic illness: A comparison of Huntington’s disease and multiple sclerosis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2012, 200, 716–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, K.A.; Dagenais, M.; Gammage, K.L. Is a picture worth a thousand words? Using photo-elicitation to study body image in middle-to-older age women with and without multiple sclerosis. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffenberger, N.; Gutweniger, S.; Kopp, M.; Seeber, B.; Sturz, K.; Berger, T.; Gunther, V. Impaired body image in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2011, 124, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusik, E.; Durmala, J.; Ksciuk, B.; Matusik, P. Body composition in multiple sclerosis patients and its relationship to the disability level, disease duration and glucocorticoid therapy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taul-Madsen, L.; Connolly, L.; Dennett, R.; Freeman, J.; Dalgas, U.; Hvid, L.G. Is aerobic or resistance training the most effective exercise modality for improving lower extremity physical function and perceived fatigue in people with multiple sclerosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 2032–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannath, V.A.; Filippini, G.; Di Pietrantonj, C.; Asokan, G.V.; Robak, E.W.; Whamond, L.; Robinson, S.A. Vitamin D for the management of multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9, CD008422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, N.E.; Jackson-Tarlton, C.S.; Vacchi, L.; Merdad, R.; Johnston, B.C. Dietary interventions for multiple sclerosis-related outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 5, CD004192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. The NEO Personality Inventory: Using the five-factor model in counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 2011, 69, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Drake, A.S.; Eizaguirre, M.B.; Zivadinov, R.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Chapman, B.P.; Benedict, R.H. Trait neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness in multiple sclerosis: Link to cognitive impairment? Mult. Scler. 2018, 24, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, M.G.; Cuzzola, M.F.; Latella, D.; Impellizzeri, F.; Todaro, A.; Rao, G.; Manuli, A.; Calabro, R.S. How personality traits affect functional outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis: A scoping review on a poorly understood topic. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 46, 102560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, W. Depression, neuroticism, and the discrepancy between actual and ideal self-perception. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 88, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uliaszek, A.A.; Zinbarg, R.E.; Mineka, S.; Craske, M.G.; Sutton, J.M.; Griffith, J.W.; Rose, R.; Waters, A.; Hammen, C. The role of neuroticism and extraversion in the stress-anxiety and stress-depression relationships. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2010, 23, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C.G.; Cooper, Z.; Shafran, R. Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behav. Res. Ther. 2003, 41, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.; Rieger, E.; Byrne, D. A longitudinal investigation of the mediating role of self-esteem and body importance in the relationship between stress and body dissatisfaction in adolescent females and males. Body Image 2013, 10, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechan, I.; Kvalem, I.L. Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eat. Behav. 2015, 17, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Saez, S.; Pascual, A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Echeburua, E. The effect of body dissatisfaction on disordered eating: The mediating role of self-esteem and negative affect in male and female adolescents. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 1098–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.P. Mood and self-esteem of persons with multiple sclerosis following an exacerbation. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 59, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikula, P.; Nagyova, I.; Krokavcova, M.; Vitkova, M.; Rosenberger, J.; Szilasiova, J.; Gdovinova, Z.; Stewart, R.E.; Groothoff, J.W.; van Dijk, J.P. Self-esteem, social participation, and quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 984–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, M.; Salmen, A.; Barin, L.; Puhan, M.A.; Calabrese, P.; Kamm, C.P.; Gobbi, C.; Kuhle, J.; Manjaly, Z.M.; Ajdacic-Gross, V.; et al. Development and validation of the Self-reported Disability Status Scale (SRDSS) to estimate EDSS-categories. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 42, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Srivastava, S. The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- Costa Mastrascusa, R.; de Oliveira Fenili Antunes, M.L.; de Albuquerque, N.S.; Virissimo, S.L.; Foletto Moura, M.; Vieira Marques Motta, B.; de Lara Machado, W.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Quarti Irigaray, T. Evaluating the complete (44-item), short (20-item) and ultra-short (10-item) versions of the Big Five Inventory (BFI) in the Brazilian population. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). Available online: https://www.apa.org/obesity-guideline/rosenberg-self-esteem.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Cooper, P.; Taylor, M.; Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C.G. The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1987, 6, 485–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M.; Olmsted, M.P.; Bohr, Y.; Garfinkel, P.E. The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol. Med. 1982, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, N.M.; Jung, M.; Cook, A.; Lopez, N.V.; Ptomey, L.T.; Herrmann, S.D.; Kang, M. Psychometric properties of the 26-item Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26): An application of Rasch analysis. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Moore, E.W.G.; Yagiz, G. How and why to follow best practices for testing mediation models with missing data. Int. J. Psychol. 2025, 60, e13257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C.; White, I.R.; Lee, D.S.; van Buuren, S. Missing data in clinical research: A tutorial on multiple imputation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2021, 37, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buuren, S.v.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.B. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, T. Lavaan.Mi: Fit Structural Equation Models to Multiply Imputed Data. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lavaan.mi (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Jorgensen, T.; Pornprasertmanit, S.; Schoemann, A.M.; Rosseel, Y. SemTools: Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Sim, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Suh, Y. Sample size requirements for simple and complex mediation models. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2022, 82, 76–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Textor, J.; van der Zander, B.; Gilthorpe, M.S.; Liskiewicz, M.; Ellison, G.T. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: The R package ‘dagitty’. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, P.; Stice, E.; Shaw, H.; Gau, J.M.; Ohls, O.C. Age effects in eating disorder baseline risk factors and prevention intervention effects. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Buono, V.; Bonanno, L.; Corallo, F.; Cardile, D.; D’Aleo, G.; Rifici, C.; Sessa, E.; Quartarone, A.; De Cola, M.C. The relationship between body image, disability and mental health in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, L.; Vandereycken, W.; Luyten, P.; Soenens, B.; Pieters, G.; Vertommen, H. Personality prototypes in eating disorders based on the big five model. J. Pers. Disord. 2006, 20, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E.; Kiropoulos, L.A. Mediating the relationship between neuroticism and depressive, anxiety and eating disorder symptoms: The role of intolerance of uncertainty and cognitive flexibility. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 4, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingemans, A.; Danner, U.; Parks, M. Emotion regulation in binge eating disorder: A review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingley, S.; Youssef, G.J.; Manning, V.; Graeme, L.; Hall, K. Distress tolerance across substance use, eating, and borderline personality disorders: A meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 300, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.S. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. J. Pers. 2000, 68, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.S. Neuroticism and health as individuals age. Pers. Disord. 2019, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, S.J.; Jackson, J.J. The role of vigilance in the relationship between neuroticism and health: A registered report. J. Res. Pers. 2018, 73, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, E.K.; Weston, S.J.; Turiano, N.A.; Aschwanden, D.; Booth, T.; Harrison, F.; James, B.D.; Lewis, N.A.; Makkar, S.R.; Mueller, S.; et al. Is healthy neuroticism associated with health behaviors? A coordinated integrative data analysis. Collabra Psychol. 2020, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, S.J.; Jackson, J.J. Identification of the healthy neurotic: Personality traits predict smoking after disease onset. J. Res. Pers. 2015, 54, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiano, N.A.; Whiteman, S.D.; Hampson, S.E.; Roberts, B.W.; Mroczek, D.K. Personality and substance use in midlife: Conscientiousness as a moderator and the effects of trait change. J. Res. Pers. 2012, 46, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turiano, N.A.; Mroczek, D.K.; Moynihan, J.; Chapman, B.P. Big 5 personality traits and interleukin-6: Evidence for “healthy neuroticism” in a US population sample. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 28, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, M.; Robinson, S.A.; Bisson, A.N.; Lachman, M.E. The relationship of personality and behavior change in a physical activity intervention: The role of conscientiousness and healthy neuroticism. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 166, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, I.; Yuen, K. Association between healthy neuroticism and eating behavior as revealed by the NKI Rockland sample. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.F.; Reid, F.; Lacey, J.H. The SCOFF questionnaire: A new screening tool for eating disorders. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, N.; Baumhackl, U.; Kopp, M.; Gunther, V. Effects of psychological group therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2003, 107, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, T.; de Sire, A.; Agostini, F.; Bernetti, A.; Salome, A.; Altieri, M.; Di Piero, V.; Ammendolia, A.; Mangone, M.; Paoloni, M. Efficacy of interoceptive and embodied rehabilitative training protocol in patients with mild multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1095180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, D.; O’Keeffe, D.F.; Seery, C.; Eccles, D.F. The association between body image and psychological outcomes in multiple sclerosis. A systematic review. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2025, 93, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogosian, A.; Hughes, A.; Norton, S.; Silber, E.; Moss-Morris, R. Potential treatment mechanisms in a mindfulness-based intervention for people with progressive multiple sclerosis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, R.; Mair, F.S.; Mercer, S.W. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis—A feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocaloski, S.; Elliott, S.; Brotto, L.A.; Breckon, E.; McBride, K. A mindfulness psychoeducational group intervention targeting sexual adjustment for women with multiple sclerosis and spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Sex. Disabil. 2016, 34, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, O.; Probst, Y.; Haartsen, J.; McMahon, A.T. The role of multidisciplinary MS care teams in supporting lifestyle behaviour changes to optimise brain health among people living with MS: A qualitative exploration of clinician perspectives. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e14042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, A.; Taylor, B.V.; Blizzard, L.; Simpson-Yap, S.; Oddy, W.H.; Probst, Y.C.; Black, L.J.; Ponsonby, A.L.; Broadley, S.A.; Lechner-Scott, J.; et al. Associations between diet quality and depression, anxiety, and fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 63, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Strober, L.B. Anxiety and depression in multiple sclerosis (MS): Antecedents, consequences, and differential impact on well-being and quality of life. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 44, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Kuiper, R.M.; Grasman, R.P. A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol. Methods 2015, 20, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 55 (20.0%) |

| Female | 218 (79.3%) |

| Non-binary | 2 (<1.0%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Anglo-Celtic | 211 (76.7%) |

| Asian (Eastern, Southern, Southeastern) | 8 (2.9%) |

| Indigenous Australian and/or Torres Strait Islander | 12 (4.4%) |

| Hispanic or Latin American | 4 (1.5%) |

| Middle Eastern | 3 (1.1%) |

| African American | 22 (8.0%) |

| Other | 15 (5.5%) |

| Country of current residence | |

| Australia | 145 (52.7%) |

| New Zealand | 6 (2.2%) |

| UK | 14 (5.1%) |

| USA | 88 (32.0%) |

| Other | 22 (8.0%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Postgraduate | 51 (18.6%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 76 (27.6%) |

| Year 12 (high school) or equivalent | 38 (13.8%) |

| Diploma or certificate level | 103 (37.5%) |

| Below high school | 7 (2.6%) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married | 173 (62.9%) |

| Partnered/De facto | 13 (4.7%) |

| Single/Never married | 38 (13.8%) |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated | 51 (18.6%) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time | 110 (40.0%) |

| Part-time/Casual | 73 (26.6%) |

| Unemployed | 92 (33.5%) |

| MS type | |

| Relapsing-remitting | 185 (68.3%) |

| Progressive (primary or secondary) | 80 (29.1%) |

| Other/Not sure | 10 (3.6%) |

| MS relapses in the past 12 months | |

| None | 129 (46.9%) |

| 1 to 3 | 119 (43.3%) |

| More than 3 | 27 (9.8%) |

| Current MS relapse at the time of survey | |

| Yes | 75 (27.3%) |

| No | 200 (72.7%) |

| Current disease-modifying treatment/s | |

| Yes | 185 (67.3%) |

| No | 90 (32.7%) |

| Level of ambulation | |

| SRDSS < 3.5 | 117 (42.5%) |

| SRDSS 4 to 6.5 | 94 (34.2%) |

| SRDSS > 7 | 18 (6.6%) |

| Missing | 46 (16.7%) |

| Diagnosis | N (% Sample) |

|---|---|

| Depressive disorder diagnosis | |

| Total | 147 (53.5%) |

| Current | 104 (37.8%) |

| Recovered/lifetime | 43 (15.6%) |

| Anxiety disorder diagnosis | |

| Total | 130 (47.3%) |

| Current | 114 (41.5%) |

| Recovered/lifetime | 16 (5.8%) |

| Eating disorder diagnosis | |

| Total | 58 (21.1%) |

| Current | 39 (14.2%) |

| Recovered/lifetime | 19 (6.9%) |

| Depressive disorder type a | |

| Major depressive disorder (incl. post-natal depression) | 52 (18.9%) |

| Persistent depressive disorder | 42 (10.4%) |

| Premenstrual dysphoric disorder | 7 (1.7%) |

| Not sure/other | 55 (13.6%) |

| Anxiety disorder type a | |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) | 73 (26.6%) |

| Panic disorder | 16 (5.8%) |

| Agoraphobia | 3 (1.1%) |

| Specific phobia | 7 (2.6%) |

| Social anxiety disorder | 33 (12.0%) |

| Health/illness anxiety | 7 (2.6%) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 13 (4.7%) |

| Not sure/other | 10 (3.6%) |

| Eating disorder type a | |

| Anorexia nervosa (restricting and binge/purging) | 34 (12.4%) |

| Bulimia nervosa (purging and non-purging) | 26 (9.5%) |

| Binge eating disorder | 4 (1.5%) |

| Currently taking antidepressant or anti-anxiety medication | |

| Yes | 132 (48.0%) |

| No | 143 (52.0%) |

| Variables | Cronbach’s α | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Neuroticism (BFI) | 0.82 | 24.87 | 6.56 | – | ||||||

| 2. Self-esteem (RSES) | 0.87 | 13.87 | 5.69 | −0.50 ** | – | |||||

| 3. Body dissatisfaction (BSQ) | 0.90 | 24.73 | 9.55 | 0.37 ** | −0.43 ** | – | ||||

| 4. DE symptoms (EAT-26) | 0.94 | 13.86 | 11.22 | 0.14 * | −0.37 ** | 0.57 ** | – | |||

| 5. Age (years) | - | 43.03 | 12.88 | −0.18 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.36 ** | – | ||

| 6. BMI | - | 29.13 | 11.38 | 0.00 | −0.13 | 0.19 ** | −0.06 | −0.01 | – | |

| 7. Ambulation level (SRDSS) | - | - | - | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.25 ** | 0.02 | – |

| Model Pathway | β | SE | t | p | LL 95% CI | UL 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism → Self-esteem (a1) | −0.38 (−0.44) | 0.05 | −7.88 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.20 |

| Neuroticism → Body dissatisfaction (a2) | 0.28 (0.19) | 0.10 | 2.83 | 0.005 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Self-esteem → DE symptoms (b1) | −0.26 (−0.13) | 0.13 | −2.06 | 0.039 | −0.46 | −0.05 |

| Body dissatisfaction → DE symptoms (b2) | 0.67 (0.57) | 0.07 | 9.76 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.80 |

| Self-esteem → Body dissatisfaction (d) | −0.47 (−0.27) | 0.12 | −3.90 | <0.001 | −0.70 | −0.23 |

| Total model effect | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.11 | 1.36 | 0.173 | −0.07 | 0.37 |

| Direct effect (c’) | −0.26 (−0.15) | 0.10 | −2.49 | 0.013 | −0.46 | −0.05 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.40 (0.22) | 0.08 | 5.06 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.57 |

| Neuroticism → Self-esteem → DE symptoms (Ind1) | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.05 | 1.98 | 0.048 | 0.01 | 0.20 |

| Neuroticism → Body dissatisfaction → DE symptoms (Ind2) | 0.18 (0.11) | 0.07 | 2.74 | 0.006 | 0.06 | 0.33 |

| Neuroticism → Self-esteem → Body dissatisfaction → DE symptoms (Ind3) | 0.12 (0.07) | 0.04 | 2.99 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.20 |

| Pairwise comparisons of indirect effects | ||||||

| Ind1–Ind2 | −0.09 (−0.05) | 0.09 | −0.98 | 0.326 | −0.26 | 0.09 |

| Ind1–Ind3 | −0.02 (−0.01) | 0.06 | −0.29 | 0.774 | −0.15 | 0.11 |

| Ind2–Ind3 | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.09 | 0.77 | 0.440 | −0.10 | 0.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiropoulos, L.; Krug, I.; Dang, P.L. Eating Disorder Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis: Relationships Between Neuroticism, Body Dissatisfaction, and Self-Esteem. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101609

Kiropoulos L, Krug I, Dang PL. Eating Disorder Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis: Relationships Between Neuroticism, Body Dissatisfaction, and Self-Esteem. Nutrients. 2025; 17(10):1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101609

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiropoulos, Litza, Isabel Krug, and Phuong Linh Dang. 2025. "Eating Disorder Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis: Relationships Between Neuroticism, Body Dissatisfaction, and Self-Esteem" Nutrients 17, no. 10: 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101609

APA StyleKiropoulos, L., Krug, I., & Dang, P. L. (2025). Eating Disorder Symptoms in Multiple Sclerosis: Relationships Between Neuroticism, Body Dissatisfaction, and Self-Esteem. Nutrients, 17(10), 1609. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17101609