Highlights

- Opuntia ficus-indica exerts health beneficial effects that are indicative of its potential use in obesity prevention.

- Opuntia cactus could be used as a natural means for the development of functional foods.

- While the Opuntia plant resource most commonly used in preclinical studies is cladode extract, dehydrated cacti and derivatives such as flour or plant fibers have also been used in clinical studies.

Abstract

The plants of the Opuntia genus mainly grow in arid and semi-arid climates. Although the highest variety of wild species is found in Mexico, Opuntia spp. is widely distributed throughout the world. Extracts of these cacti have been described as important sources of bioactive substances that can have beneficial properties for the prevention and treatment of certain metabolic disorders. The objective of this review is to summarise the presently available knowledge regarding Opuntia ficus-indica (nopal or prickly pear), and some other species (O. streptacantha and O. robusta) on obesity and several metabolic complications. Current data show that Opuntia ficus-indica products used in preclinical studies have a significant capacity to prevent, at least partially, obesity and certain derived co-morbidities. On this subject, the potential beneficial effects of Opuntia are related to a reduction in oxidative stress and inflammation markers. Nevertheless, clinical studies have evidenced that the effects are highly contingent upon the experimental design. Moreover, the bioactive compound composition of nopal extracts has not been reported. As a result, there is a lack of information to elucidate the mechanisms of action responsible for the observed effects. Accordingly, further studies are needed to demonstrate whether Opuntia products can represent an effective tool to prevent and/or manage body weight and some metabolic disorders.

Keywords:

Opuntia spp.; nopal; prickly pear; Opuntia ficus-indica; obesity; metabolic co-morbidities 1. Introduction

The genus Opuntia is characterised by its ability to thrive in challenging environmental conditions, given its capacity to grow in arid and semi-arid zones [1]. Opuntia plants, classified within the Cactaceae family, are notable for their globose stems adorned with thorns, referred to as cladodes. These cladodes are flat, oval, fleshy segments that bear spikes (called glochids). The genus Opuntia is further distinguished by the production of pear-shaped fruits exclusive to this genus, commonly known as prickly pears. To date, opuntioid cacti encompass over 250 species, predominantly distributed in the Americas, with additional occurrences in Asia, Africa, Oceania and certain regions of the Mediterranean area [2]. Mexico is recognised for hosting the most diverse array of species within this genus, reaching up to 126 different species of Opuntia [3].

Opuntia fruits are extensively consumed, and the products derived from the plant find applications in the pharmaceutical, food and cosmetic industries, rendering them of considerable economic significance [4]. Opuntia has been identified as a viable alternative for animal feeding due to its low water requirements and high productivity; therefore, Opuntia plantations have the potential to contribute to the development of agriculture [5]. Furthermore, Opuntia cultivations fulfil ecosystem protection functions by serving as habitats for a diverse range of living organisms, supplying raw material for soil development, offering protection against erosion and potentially participating in phytoremediation processes for contaminated water and soil [6].

For years, health benefits associated with the Opuntia genus have been documented in folk medicine, and this traditional knowledge remains highly relevant in many indigenous communities to this day [7]. From the scientific point of view, it has been observed that extracts of opuntioid cacti, obtained from fruits, cladodes or flowers, can exert beneficial properties for the prevention and treatment of certain disorders, such as obesity, type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and several types of cancer [3,8,9,10,11,12].

The health-promoting properties of Opuntia are primarily attributable to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, mainly associated with the high content of bioactive compounds. These include phenolic compounds, betalains and phytosterols, as well as certain polysaccharides and vitamins [7,13,14,15]. The presence of phytochemicals such as phenolic acids, pigments or antioxidants have been found in all Opuntia products, including roots, cladodes, seeds, fruits or juice, although the amounts vary depending on the variety and the part of the plant [3]. The content of bioactive compounds is mainly influenced by the soil where the cactus is grown and thus by the geographical area of cultivation. Moreover, this chemical profile is highly variable and contingent on climatic conditions [16]. Therefore, these variations can affect the biological properties of each variety [17].

Taking all of the above into consideration, the aim of this review is to summarise the documented knowledge concerning the beneficial effects of Opuntia spp. on obesity co-morbidities. Presently, several investigations have been conducted both in in vivo models and in humans, Opuntia ficus-indica cactus (also known as nopal or prickly pear) emerging as the most extensively investigated species in the majority of these studies. Additionally, some research has been conducted with Opuntia robusta and Opuntia streptacantha.

2. Search Strategy

A bibliographic search was conducted to identify studies included in the PubMed medical database up to May 2023, using different combinations of the following keywords: obesity, obesity management, body weight, anti-obesity agents, weight loss, overweight, metabolic syndrome, Opuntia and cactus. Therefore, only original articles written in English were included. From the initially collected articles, a total of 19 studies were retained following the screening process, which involved evaluating the title, abstract and full text.

3. Effects of Opuntia spp. on Obesity-Related Co-Morbidities in Preclinical Studies

The most investigated cactus species in in vivo experimental models is Opuntia ficus-indica. In fact, there is only one study conducted on a different species, specifically the investigation reported by Héliès-Toussaint et al. (2020) focusing on Opuntia streptacantha [18]. These in vivo studies have been performed using either genetic obese animal models or diet-induced obesity models (Table 1). Morán-Ramos et al. (2012) [10] aimed at studying the effect of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes in Zucker (fa/fa) rats, a model of genetic obesity. For this purpose, rats were divided into two groups and were fed for seven weeks with either a control diet or a diet supplemented with a dehydrated extract of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes, collected in Mexico. Diets were supplemented with an amount of Opuntia ficus-indica sufficient to yield 4% of fibre, replacing the cellulose content present in the control diet. No changes were observed in weight gain, although the daily food intake was increased in the Opuntia ficus-indica-treated group (+2.1%, p < 0.01). These animals showed decreased serum cholesterol (−31%, p < 0.001), alanine aminotransferase (−44%, p < 0.05) (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (−30%, p < 0.01) (AST) levels, whereas serum adiponectin levels significantly increased in the supplemented group (+75%, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

Effects of Opuntia products in animal models.

A substantial body of research has also focused on the effects of cladode extracts from Opuntia ficus-indica in murine models (mouse or rat) characterised by obesity induced through high-fat feeding. These studies utilised diets supplying fat with the range of 30–60% of energy, or alternatively, a cafeteria diet. In this line, Aboura et al. (2019) [19] studied the effect of an aqueous extract of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes on mice fed with a high-fat diet (60% of energy from fat), supplemented or not with 1% of the infusion of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes (administered daily in the drinking water) for six weeks. The infusion contained 6.99 mg of polyphenols/100 mL. At the end of the experimental period, the mice fed with the high-fat diet (HFD) significantly increased both body and adipose tissue weight when compared with the mice fed with the standard diet (p < 0.05). The mice supplemented with the Opuntia ficus-indica infusion showed lower values for both parameters (p < 0.05), although they did not reach the values observed in the control mice. This suggests that the supplementation partially prevented obesity. The same results were found in triglyceride (TG) (−18%, p < 0.05), total cholesterol (−24%, p < 0.01), glucose (−32%, p < 0.05), insulin (−24%, p < 0.05), interleukin 6 (IL-6) (−33%, p < 0.05) and tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) (−20%, p < 0.05) plasma levels.

Moreover, the authors measured the gene expression of leptin and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α, but not IL-10) in adipose tissue, noting that it was higher in mice fed with the obesogenic diet. Interestingly, the infusion of Opuntia ficus-indica totally prevented this effect (p < 0.05). In the case of adiponectin, despite the decrease in its gene expression induced by the high-fat diet, the infusion was not able to significantly prevent this effect. In summary, the administration of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes as an infusion exhibits a protective effect against obesity and inflammation induced by a high-fat diet.

Sánchez-Tapia et al. (2017) [20] studied the potential of Opuntia ficus-indica supplementation to mitigate the metabolic repercussions of obesity by modifying the gut microbiota and preventing metabolic endotoxemia in rats subjected to a high-fat high-sucrose diet. During the first seven months of the experimental period, rats were fed with a standard diet or a high fat-sucrose diet (45% energy from fat added to the diet and 5% from sucrose added to the drinking water). Subsequent to this period, rats continued with their respective diets. However, the animals receiving the obesogenic diet were distributed into four groups for an additional month: rats fed with a standard diet, supplemented or not with dehydrated Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes that provided 5% of dietary fibre from nopal instead of cellulose, and rats on the same obesogenic diet, supplemented or not with the dehydrated Opuntia ficus-indica at the equivalent dose.

At the end of the experimental period, rats subjected to the obesogenic diet for eight months showed significantly higher body weight than the other groups (+23.6%). By contrast, rats from cohorts that received the standard diet throughout the entire experimental period, as well as rats from the group initially exposed to the obesogenic diet and subsequently transitioned to the standard diet supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica, displayed the lowest values in this parameter. The remaining groups exhibited intermediate values, and it is important to note that these differences were not attributed to variations in food intake.

Rats fed the obesogenic diet during the whole treatment period showed higher glucose and insulin serum levels, although Opuntia ficus-indica supplementation prevented these increases. Moreover, this enriched diet completely adverted the boost in serum triglyceride (p = 0.0054), total-cholesterol (p < 0.0001), LDL-cholesterol (p < 0.0001) and leptin (p < 0.0001) increases induced by the high-fat feeding, although leptin was an exception. These results demonstrate that Opuntia ficus-indica was also effective in preventing obesity-related comorbidities.

To ascertain whether the effects of Opuntia ficus-indica were related to alterations in gut microbiota, an investigation into bacterial diversity was conducted. The control group exhibited the highest diversity, while the group of rats fed the obesogenic diet without supplementation throughout the entire experimental period displayed the lowest. The remaining groups demonstrated intermediate levels of diversity. At the phylum level, it was observed that the abundance of Bacteroidetes increased with respect to that of Firmicutes in the rats supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica. At the genus level, the supplementation boosted Anaeroplasma, Prevotella and Ruminucoccus and reduced Faecalibacterium, Clostridium and Butyricicoccus.

In addition, the obesogenic diet led to a reduction in intestinal mucus layer thickness compared with the control group, and this effect was concomitant with a decrease in intestinal occludin-1 protein. Opuntia ficus-indica supplementation avoided these effects, suggesting an improvement in intestinal permeability. Moreover, Opuntia ficus-indica attenuated the elevation of serum lipopolysaccharide induced by the diet.

In assessing the expression of genes related to oxidative stress and inflammation in adipose tissue, the authors observed that Opuntia ficus-indica supplementation reduced the expression of leptin, NADPH oxidase (Nox), Tnf-α and amyloid precursor protein (App) genes. Furthermore, the expression of Tnf-α gene was lower than in the control group.

Héliès-Toussaint et al. (2020) [18] analysed the effects of a cladode extract from Opuntia ficus-indica on Sprague–Dawley rats fed with a high-fat diet (30% of energy from fat), supplemented or not with 0.5 w/w of the extract for eight weeks. At the end of the experimental period, increased final body weight was observed in both groups fed with a high-fat diet, compared to the control group. However, rats supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica exhibited a significantly reduced body mass gain compared to rats subjected to the non-supplemented high-fat diet (−12.5%, p < 0.05). Additionally, supplementation with Opuntia ficus-indica led to a reduction in abdominal fat weight (−20%), serum glucose, insulin levels (−20%) and serum triglyceride levels compared to the group fed with the non-supplemented high-fat diet, although these changes did not reach statistical significance. The group supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica showed an increased amount of triglycerides in faeces compared to the control group (+23%, p < 0.05). This finding may align with a reduction in body weight. High-fat feeding led to decreased adiponectin serum levels and increased leptin serum levels, effects that were significantly prevented by Opuntia ficus-indica supplementation (+26% of adiponectin levels and −30% of leptin levels).

Urquiza-Martínez et al. (2020) [21] studied the hypothalamic function through the introduction of Opuntia ficus-indica flour in either a standard diet or a high-fat diet. C57Bl/6J mice were initially stratified into two cohorts, with one group receiving a standard diet and the other a high-fat diet (60% of energy from fat) over a period of twelve weeks. Subsequently, each diet cohort was further divided into two subgroups: one supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes flour (17% w/w) and the other enriched with fibre (an amount similar to that provided by the cactus flour), extending the dietary intervention for additional weeks.

The cactus flour had no effect on body weight when added to the standard diet. However, it normalised body weight when it was administered with the high-fat diet. This anti-obesity effect was due, at least in part, to the reduction observed in epididymal (−57.9%, p < 0.001) and retroperitoneal (−70.3%, p < 0.001) adipose tissues. In addition to its anti-obesity effect, Opuntia-ficus indica flour improved glucose metabolism control, as evidenced by the outcomes of the glucose tolerance test. Opuntia ficus-indica flour increased food intake when administered in conjunction with the standard diet. Conversely, its addition to the high-fat diet resulted in a reduction in this parameter. Therefore, the investigation focused on feeding behaviour, a pivotal aspect in the regulation of food intake. The integration of cactus flour with the standard diet delayed the point of satiation, while its combination with the high-fat diet resulted in an earlier onset of satiation.

Micrography performed on hypothalamic coronal sections showing the arcuate nucleus revealed no statistically significant differences in the total density of microglia among the experimental groups. However, activated microglial cells were more abundant in mice fed the high-fat diet compared to those on the standard diet. The cactus flour, in combination with the obesogenic diet, reduced the activated microglial density, albeit not reaching the same level observed in mice fed the standard diet. The authors concluded that Opuntia ficus-indica flour likely prevented obesity by mitigating the activation of microglial cells within the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus.

Using a cafeteria diet instead of a high-fat diet to induce obesity in rats, Chekkal et al. (2020) [22] sought to assess the impact of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes on obesity and dyslipidemia in the rat model. Male Wistar rats were divided into two groups, with one receiving a cafeteria diet (CD group; 50% hyperlipidic diet + 50% junk food) either supplemented or not with Opuntia ficus-indica cladode extract (OFI group; 50 g/100 g diet), for 30 days. At the end of the experimental period, Opuntia ficus-indica extract prompted a reduction in both body weight (−20%) and adipose tissue weight (−45%). Moreover, a decrease in food intake (−10%) was also observed in rats fed the CD supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica extract. Unfortunately, a pair-fed group was not included in the experimental design, preventing a clear distinction between the direct effects of the extract and those associated with the reduction in food intake. Regarding glycaemic control, a mitigation in serum glucose and insulin (−29 and −64%, respectively) levels was observed in the Opuntia ficus-indica-treated group. In addition, decreased glycated haemoglobin (−31%) and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR index −41%) were observed in this cohort in comparison with the control group. With regards to cholesterolaemia, the treated group showed a reduction in serum total cholesterol (−21%) level. Additionally, serum triglycerides and very-low-density lipoprotein-triglyceride (VLDL-triglycerides) levels decreased by 35% and 20%, respectively. In an effort to delve deeper into the mechanism of action underlying the effects induced by Opuntia ficus-indica extract, the authors focused on the oxidative status. Thus, they observed a significant decline in lipid peroxidation, as measured by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), in both the serum (−29%) and adipose tissue (−83%) of the Opuntia ficus-indica-treated group. This reduction in lipid peroxidation was also evident in VLDL. Furthermore, the authors assessed the enzymatic activity of paraoxonase 1 (PON-1), a protein involved in protecting against lipid peroxidation through the hydrolysis of xenobiotics. In fact, PON-1 plays an anti-atherogenic role, as this enzyme is bound to HDL and inhibits the oxidation of lipoproteins and lipids, decreasing the degree of inflammation [27]. In the Opuntia ficus-indica-treated group, there was a significant boost in serum PON-1 activity, showing a rise of 27% in serum and 47% in HDL-cholesterol. With regards to antioxidant enzymes, while superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity remained unchanged in serum, the activities of both glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and catalase (CAT) were elevated in the plasma of rats supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica extract (+73% and +64%, respectively). In the adipose tissue, the Opuntia ficus-indica-treated group exhibited a significant rise in SOD and CAT activities (+67% and +40%, respectively). Collectively, these findings indicate that Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes contribute to preventing weight gain, improving glycemic balance and oxidative status.

Cladode extracts of Opuntia ficus-indica have also been investigated in alternative dietary models. In a study conducted by Cárdenas et al. (2019) [23], rats were subjected to a high-fructose diet, with Opuntia ficus-indica extract incorporated into their drinking water over a period of three weeks. Following the period, animals were maintained on the same diet and divided into three groups: (a) the control group, receiving only water, (b) the nopal group, where rats were orally administered 4.36 g/kg body weight per day of freshly daily prepared Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes extract, and (c) the mucilage group, wherein rats were orally administered 500 mg/kg body weight per day of mucilage fibre extract, over an additional 8-week period. The findings indicated that the rats receiving fructose in drinking water exhibited increased serum triglycerides and abdominal circumference. However, the administration of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes extract significantly decreased plasma triglyceride levels (−43.4%, p < 0.05), with no observable changes in the abdominal circumference. In this study, the results suggested that the mucilage fibre extract was less effective than the Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes extract in achieving the observed effects.

In addition to cladode extracts, other Opuntia ficus-indica extracts have been used in several studies. Bounihi et al. (2017) [24] addressed a research to investigate the anti-adiposity and anti-inflammatory effects of prickly pear fruit vinegar of Opuntia ficus-indica in rats fed with an obesogenic diet for eight weeks. The control group received a standard diet, while an additional cohort was administered a high-fat diet (45% of energy from fat). Subsequently, three distinct groups were fed with the same high-fat diet supplemented with vinegar of the prickly pear at different doses: 3.5, 7 and 14 mL/kg body weight/day. The results revealed an elevation in both ultimate body weight and visceral adipose depot weights (mesenteric, epididymal and perirenal) among rats subjected to the high-fat diet. However, supplementation with prickly pear fruit vinegar demonstrated a significant mitigation of both body weight increase (−18.7%, −30.5% and −33% in final body weight by doses of 3.5, 7 or 14 mL/kg body weight/day, respectively) and total visceral fat depot increase (−18.7%, −30.5% and −33% in final body weight by doses of 3.5, 7 or 14 mL/kg body weight/day, respectively) across all administered doses. The high-fat feeding led to higher concentrations of plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) and coronary risk index (CRI). These effects were completely adverted through the administration of the prickly pear fruit vinegar, with efficacy demonstrated at all specified doses. The levels of leptin and TNF-α in both plasma and visceral adipose tissue were increased by the HFD, concomitant with a reduction in adiponectin levels. Prickly pear fruit vinegar successfully adverted these effects at all given doses.

Verón et al. (2019) [25] conducted an interesting study in an obese mice model which examined the beneficial effects of fermented Opuntia ficus-indica juice, either in isolation or fermented with a probiotic. For this purpose, Opuntia ficus-indica fruits, harvested in Argentina, were processed to obtain pasteurised juice. A portion of the juice was subsequently subjected to fermentation using Lactobacillus plantarum S-811, a strain previously isolated from Opuntia ficus-indica. The obese mice model was established by administering a high-fat diet to C57BL-6J mice. The animals were allocated into four experimental cohorts: the control group (C group) received a standard diet, the obese group was subjected to a high-fat diet (60.3% kcal as fat) (HFD group), a third group was fed with the high-fat diet supplemented solely with pasteurised Opuntia ficus-indica juice (5 mL/day/mouse), and a fourth cohort was administered the high-fat diet supplemented with pasteurised Opuntia ficus-indica juice and fermented with the probiotic (5 mL/day/mouse of 1.2 × 109 CFU/mL). This dietary regimen was maintained for seven weeks. In this study, the authors characterised the extract and observed a substantial enhancement in the content of both betanin and indicaxanthin (+41% and +38%, respectively) through the process of fermentation. These compounds are the main betalains present in this Opuntia species. Mice treated with the fermented Opuntia ficus-indica juice showed lower values in body weight, adipose tissue index, plasma triglycerides (−25%), total cholesterol (−25%), glucose (−25%), insulin (−35%) and HOMA-IR index (−51%), although these values did not reach the levels found in the control group. The non-fermented Opuntia ficus-indica juice failed to significantly mitigate either body weight or adiposity index in comparison with obese mice, although it did result in a notable reduction in both triglycerides and total cholesterol levels. Regarding leptin in plasma, obese mice showed an increase in leptin levels (hyperleptinemia), which were not prevented by the administration of Opuntia ficus-indica juices.

Due to the fact that probiotics, like Lactobacillus plantarum S-811, can regulate gut inflammation, the authors also determined interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-10 cytokine levels. In this context, high-fat feeding did not increaseIL-10 levels in the serum, although it did significantly increase the concentration of gut IFN-γ. Nevertheless, within the gut, neither fermented nor non-fermented Opuntia ficus-indica juices induced alterations in these gut cytokines, in comparison with the obese mice group. Consequently, the authors concluded that fermented Opuntia ficus-indica juice exhibited anti-obesity properties, with the fermentation process enhancing the juice’s capacity to stimulate antioxidant defences.

The beneficial effects of Opuntia have also been analysed in combination with other foodstuffs. In the study reported by Rosas-Campos et al. (2022) [26], C57BL/6J mice were fed a high-fat diet (35% of energy from fat) in conjunction with high-carbohydrate beverage (2.31% fructose, 1.89% sucrose), for 16 weeks. In addition, during the initial eight weeks, the diet was supplemented with 10% Opuntia ficus-indica and 20% of a composite Mexican food mixture (referred to as MexMix), consisting of Theobroma cacao and Acheta domesticus, each comprising 10% w/w. As expected, the obesogenic diet caused an increase in mice body weight, visceral fat pad, epididymal fat pad, triglyceride levels, serum glucose and insulin levels, total- and LDL-cholesterol levels, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), leptin, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and resistin levels. Moreover, through hematoxylin-eosin staining, the authors observed that the high-fat diet increased adipocyte size and markers indicative of inflammatory infiltrates. Supplementation with MexMix significantly prevented all these effects (body weight −23%, visceral fat pad −71.7%, epididymal fat pad −39%, serum triglycerides −15.1%, serum glucose −22.5%, serum insulin −51%, total cholesterol −30.4%, LDL-cholesterol −73.3%, GIP -34.2%, leptin −74.4%, PAI-1 −41% and resistin −41%) and demonstrated the potential to reverse the reduction in insulin sensitivity induced by high-fat feeding. However, there were no changes in adiponectin, glucagon and serum adipokines. Taking into account that Opuntia ficus-indica was supplemented together with other foods, it became challenging to differentiate the specific impact of the cactus from the effects attributed to the other foods, or even the combined influence of all components.

As indicated previously, there is only one study documented in the literature that examines the effects of an Opuntia species different from Opuntia ficus-indica. Héliès-Toussaint et al. (2020) [18] not only investigated the effects of an eight-week supplementation with lyophilised cladode powder from Opuntia ficus-indica but also explored the impacts of cladode powder from Opuntia streptacantha. The study conducted an analysis of the proximal composition of the extracts, revealing statistical differences between both Opuntia species. Opuntia streptacantha presented a greater fibre content (6.52%), whereas Opuntia ficus-indica displayed the highest ash content (14.2%). Moreover, Opuntia streptacantha demonstrated the highest concentration of phenolic compounds and exhibited the highest antioxidant capacity. Specifically, in the case of Opuntia streptacantha, the concentration of gallic acid within phenolic acids was 65.1 µg/g, the quercetin content within flavonoids measured 19.0 µg/g, and the antioxidant activity was determined to be 897.8 µmol of Trolox/g sample. For Opuntia ficus-indica, the concentration of gallic acid within phenolic acids measured 56.7 µg/g, while the quercetin content in flavonoids was 20.4 µg/g. Additionally, the antioxidant activity was quantified as 659.4 µmol of Trolox/g sample.

In sharp contrast with Opuntia ficus-indica, the extract obtained from Opuntia streptacantha failed to prevent the final body mass gain. The supplementation reduced abdominal fat weight, serum glucose and insulin levels, as well as serum triglyceride levels, but these changes did not reach statistical significance. The decrease in serum adiponectin levels and the boost in leptin serum levels induced by the high-fat feeding were prevented by the Opuntia streptacantha extract. These results suggest that, in the assessment of the therapeutic potential of the two Opuntia species, the consumption of Opuntia ficus-indica appears to hold greater promise in the context of obesity and related metabolic alterations management.

Summary

In summary, with the exception of a study specifically focused on a genetic obesity model (Zucker fa/fa rat), all the reported works analysing the effects of Opuntia products on obesity have been conducted in murine models, predominantly rats or mice, exhibiting diet-induced obesity. The induction methods for obesity in these experiments encompassed high-fat feeding, cafeteria diet or fructose supplementation. All the studies have centred on Opuntia ficus-indica, and the majority have analysed cladode extracts, although certain authors have employed alternative formulations such as fruit vinegar, fruit juice or flour. In addition, a single published study has been carried out using a fruit juice fermented with a probiotic, revealing this particular form to be more effective than its non-fermented counterpart. Taking into account that Opuntia ficus-indica products have been administered to animals concurrently with an obesogenic diet, the effects observed are indicative of their potential in preventing obesity.

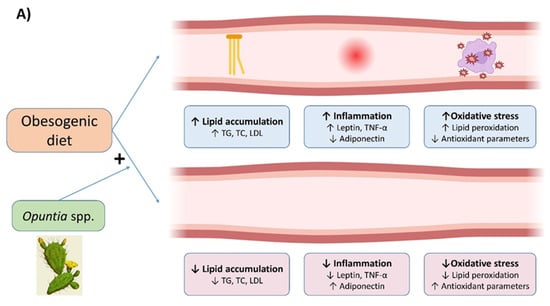

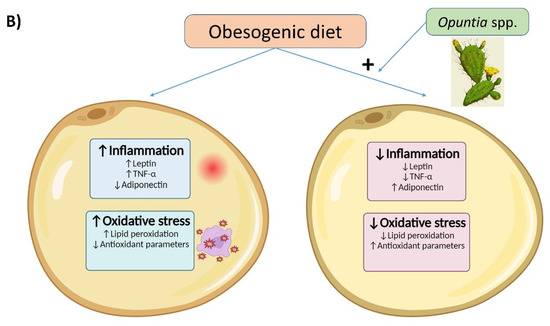

The collective evidence from published studies consistently demonstrates that all Opuntia ficus-indica products employed possess a significant capacity to prevent, at least partially, obesity and certain associated co-morbidities, such as dyslipidemias and insulin resistance (Figure 1). These beneficial effects have been substantiated across different experimental period lengths, ranging from four to eight weeks. It is noteworthy that in the majority of the studies, the composition of bioactive compounds in Opuntia ficus-indica products has not been reported. Consequently, there is a lack of information concerning the main bioactive compounds present in these products that are responsible for the observed effects. This represents a significant limitation in the current understanding of the mechanisms underlying these benefits.

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of the beneficial effects of Opuntia spp. in plasma (A) and adipose tissue (B) in animal models. TC: total cholesterol, TG: triglycerides, LDL: low-density lipoprotein, TNF-α: tumour necrosis factor-α; ↑: increase; ↓: decrease; +: diet supplementation.

There is also a study that compares the effects of cladode extracts obtained from Opuntia ficus-indica and Opuntia streptacantha, with the former being more effective in managing obesity.

The potential mechanisms underlying the observed effects have been minimally explored, and the majority of reported works have not addressed this issue. Some authors have observed a reduction in markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, two key processes involved in the development of obesity. On the other hand, the improvement in insulin sensitivity induced by high-fat feeding may be related to changes in the serum adipokine profile. Alterations in microbiota composition could also be involved in the effects induced by Opuntia ficus-indica, although there is currently insufficient data to definitively support this assertion.

4. Effects of Opuntia spp. on Obesity and Related Co-Morbidities in Clinical Studies

In the context of studies involving human subjects, akin to those conducted in animal models, the predominant focus has been on analysing the effects of Opuntia-ficus indica. Notably, only one study has explored another Opuntia species (Opuntia robusta) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical studies addressed with Opuntia products.

Linarès et al. (2007) [28] used the registered trademark NeOpuntia to study the effect of dehydrated leaves of Opuntia-ficus indica on metabolic syndrome. For this purpose, the authors carried out a randomised placebo-controlled trial involving 68 women (20–55 years-old) who exhibited metabolic syndrome and had a body mass index (BMI) ranging from 25 to 40 kg/m2. The participants were instructed to consume a supplement of Opuntia (1.6 g, three times daily; 35 women) or a placebo (33 women) for six weeks, alongside engaging in 30 min of daily physical activity. Within the placebo group, a significant reduction in HDL-C levels was observed. It is important to mention that, at the end of the study, 39% of the patients in the NeOpuntia group no longer met the diagnostic criteria for metabolic syndrome. Regarding the criterion of waist circumference > 80 cm, a component of metabolic syndrome, no alteration was noted in the placebo group after 42 days of treatment. However, within the intervention cohort (35 subjects), two volunteers no longer presented an increase in this parameter. Thus, the NeOpuntia supplement appears to contribute to the management of metabolic syndrome, although it is important to note that this study provides limited information on certain aspects.

Godard et al. (2010) [29] studied the effect of OpunDia™, a formulation comprising 75% Opuntia ficus-indica cladode extract and 25% fruit skin extract. The authors evaluated both acute and chronic beneficial effects in pre-diabetic obese men and women. To accomplish this objective, they conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 29 volunteers (20 to 50 years old). Participants were randomly assigned to either the placebo group (14 subjects) or the intervention group (15 subjects), the latter receiving a daily dose of 400 mg of OpunDia™. In the chronic study, the experimental period length was sixteen weeks. In the acute treatment, a dosage of 400 mg of OpunDia™ was administered 30 min before the ingestion of a 75 g glucose solution. In this study, the authors ran an oral glucose tolerance test and observed a decrease in blood glucose concentrations at 60, 90 and 120 min following the administration of the Opuntia bolus. In the chronic study, no discernible effects of the Opuntia treatment were found between the two groups in terms of plasma insulin, proinsulin, high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), adiponectin and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. In addition, no changes were observed in fat mass, percent of body fat and total body weight during the chronic intervention. It is important to mention that OpunDia™ revealed no adverse effects on blood, liver or kidney parameters.

Grube et al. (2013) [30] conducted a randomised controlled trial to study the efficacy and safety of a natural fibre complex obtained from dehydrated cladodes of Opuntia ficus-indica (marketed under the commercial trademark Litramine IQP G-002AS). This complex was enriched with soluble fibre from Acacia spp. gum and coprocessed with cyclodextrin. It is noteworthy that this fibre complex, owing to its lipophilic activity, demonstrated the capacity to reduce the absorption of dietary fat by binding with fats in the intestinal tract, thereby forming fat–fibre complexes. The authors recruited obese and overweight subjects (n = 123 subjects, 30 male and 93 female) with a BMI ranging from 25 to 35 kg/m2 and aged between 18 and 60 years. Following a two-week placebo run-in phase, the study comprised a twelve-week treatment phase during which subjects received either 1000 mg of IQP G-002AS or a corresponding placebo, three times daily (after breakfast, lunch and dinner). Furthermore, all subjects were instructed to adhere to a mildly hypocaloric diet throughout the fourteen weeks of the study. The prescribed diet aimed to provide 55% of energy from carbohydrates, 30% from fat and 15% from protein, with a reduction in daily caloric intake by 500 kcal. In addition, subjects received instructions to increase their physical activity to 30 min/day. Under these experimental conditions, the fibre complex containing Opuntia ficus-indica induced a reduction in body weight (−2.4 kg) compared to the placebo group. Consequently, there was a decline in BMI, as well as in waist circumference (−1.7 cm) and body fat (−1.4 kg). The authors did not observe adverse effects after the ingestion of IQP G-002AS. Following the aforementioned study, the same authors in 2015 [31] conducted another double-blind, randomised study spanning twenty-four weeks. This design involved a cohort of subjects, both male and female volunteers with obesity aged between 18 and 60 years, with a BMI ranging from 25 to 35 kg/m2. Participants had also experienced a weight loss of at least 3% in the last 3–6 months. During the trial, the volunteers received 1 g of Litramine three times/day (intervention group; n = 25) or placebo (placebo group; n = 24). Concurrently, participants in both groups were advised to increase their physical activity, and no dietary restrictions were encouraged during the experiment. At the end of the experimental period, subjects in the Litramine group exhibited a significant decrease in body weight (−0.62 ± 1.55 kg) in comparison with the placebo group, where the mean body weight increased (+1.62 ± 1.48 kg). It is important to mention that subjects treated with Litramine showed lower BMI, waist and hip circumference than subjects from the placebo group. Regarding body fat content, the intervention cohort displayed a significant decrease in fat mass compared to the placebo group. Additionally, in terms of the feeling of satiety, 60% of the volunteers in the Litramine group reported experiencing satiety, while only 12.5% in the control group had a similar feeling

Pignotti et al. (2016) [32] conducted a study to evaluate the effects of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes on improving oxidative stress and cardiometabolic risk factors in sixteen volunteers with moderated hypercholesterolaemia (LDL-C 120 mg/dL) and a BMI of 31.4 ± 5.7 kg/m2 at baseline. For this purpose, subjects were divided into two groups, with one group receiving Opuntia and the other serving as a control, with cucumber as their intake. Participants in the Nopal group adhered to their regular diet supplemented with one cup of boiled Opuntia cladodes twice a day (280 g/day), while the Cucumber group received one cup of boiled cucumber twice a day (260 g/day) as their dietary supplement. The intervention lasted two weeks following a washout period of 2–3 weeks. The results yielded no changes during the intervention period regarding BMI, body mass and percent body fat. On the other hand, both cucumber and nopal significantly increased plasma triglyceride levels, with no significant difference observed either in the response between the two groups or in changes in oxidative stress markers and lipoprotein subfractions. Therefore, based on the obtained results, the authors concluded that the potential of Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes to improve cardiometabolic risk and oxidative stress biomarkers cannot be asserted in patients with hypercholesterolaemia, at least within the experimental conditions of the study.

Aiello et al. (2018) [33] addressed an intervention study with 39 volunteers, aged 19–69 years, with at least two of these conditions: impaired glucose tolerance (fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL), slight dyslipidemia (total cholesterol 190–240 mg/dL, triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL) or waist circumference ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 in women. The aim of the study was to analyse the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of Opuntia ficus-indica. The intervention consisted of following a Mediterranean pattern diet along with consuming 500 g of pasta/week supplemented with 3% of cladode extract of Opuntia ficus-indica for 30 days, and comparing it with the group without nutritional intervention. After the experimental time, the results showed no significant differences in the percentage of fat mass or BMI in the intervention group compared to the control group; however, a significant reduction in abdominal waist was observed in both men (−2.3%) and women (−1.3%). The glycaemic levels of the intervention group were significantly reduced compared to the placebo group (−4%). Additionally, a trend towards reduced levels of serum total cholesterol was observed in the intervened group (−2.82%), although no significant changes were achieved. The authors concluded that their results confirmed the biological activity of Opuntia extracts, such as the hypoglycaemic effect observed, although more research is needed to determine a possible beneficial effect of extracts in the prevention of metabolic disorders.

In the same line, Giglio et al. (2020) [34] conducted a clinical study involving 49 Italian volunteers (13 male and 36 female), aged 40–65 years, with a mean BMI > 30 kg/m2. Subjects did not meet the requirements for a full diagnosis but exhibited one or two individual criteria associated with metabolic syndrome. Among all the participants, 31% presented hypertension, 12% were both obese and dyslipidemic, and 4% were diabetic. Subjects consumed 500 g of pasta supplemented with 3% Opuntia ficus-indica cladode extract (30% of insoluble polysaccharides) on a weekly basis over a period of one month. Participants followed the Mediterranean dietary pattern and engaged in limited physical activity. It is noteworthy that they did not alter the quantity of food consumed throughout the experimental period. After one month of treatment, BMI and body weight remained unchanged, while waist circumference (−1%), plasma glucose (−12.1%), triglycerides (−11.3%), creatinine (−2.7%) and aspartate transaminase (−16.3%) levels significantly decreased in comparison with baseline values. Moreover, although there was an increment in lesser amounts of atherogenic LDL-1, a reduction in denser LDL-2 (−26.2%) and LDL-3 (−44.6%) levels was observed.

Sánchez-Murillo et al. (2020) [35] addressed a study with 69 volunteer women (aged 40–60 years) having a BMI in the range of 27.5–29 kg/m2. Participants were divided into the control group (n = 13), without supplement administration, and the treated group (n = 56), supplemented with a daily dose of 5 g of Opuntia ficus-indica cladode in their morning meals over a period of twenty-four weeks. The Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes, harvested between 16 and 24 weeks of maturation, contained 52.75% carbohydrate, 13.51% protein, 1.55% fat and 5.83% crude fibre. No differences were found in body mass index or body fat.

Corona-Cervantes et al. (2022) [36] studied the potential of Opuntia ficus-indica to improve the health status of women with obesity by modifying the composition of intestinal microbiota. In this study, a sample of 36 female volunteers from Mexico (18–59 years) was included, with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 in the obesity group and falling within the range of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 in the normal weight group. Participants were requested not to undergo antibiotic treatment in the three months prior to the study. The obesity group was subjected to an energy-restricted diet (−500 kcal/day) supplemented with 300 g of boiled Opuntia ficus-indica, obtained from 375 g of fresh cladodes. Additionally, participants were advised to engage in a 30 min daily walk for 30 days. The control group received an equivalent amount of Opuntia ficus-indica without any energy restriction or recommendation for walking. In the obesity cohort, the supplementation of Opuntia ficus-indica led to reductions in BMI (−2.8%), weight (−2.1%), hip (−0.6%), waist/hip ratio (−1%), serum levels of glucose (−12.5%), total cholesterol (−6.3%) and HDL cholesterol (−5.1%). However, no changes were observed in the normal weight group. It is important to mention that the average age differed significantly between cohorts, with 40.6 years in the obesity group and 22.1 years in the normal weight group. Furthermore, the authors studied the association between biochemical and anthropometric markers and the diversity of intestinal microbiota found in faecal samples, observing changes in the bacterial taxa in both cohorts. In the obesity group, there was an increasing tendency in Prevotella, Roseburia, Lachnospiraceae and Clostridiaceae, while Bacteroides, Blautia and Ruminococcus exhibited a decreasing trend. In fact, Prevotella species are associated with diets rich in fibre for their capacity to digest complex carbohydrates. In the normal weight group, following the intervention, a trend towards reduced amounts of Ruminococcus and Bacteroides and an increase in Lachnospiraceae family were observed. The decrease of Bacteroidetes could potentially be related to a higher intake of fructans obtained from Opuntia. The supplementation with Opuntia ficus-indica promoted the reduction in plasma total cholesterol, glucose and triglycerides. This effect could be attributed to the presence of polyphenols and soluble and insoluble fibres, which may influence the intestinal microbiota and, subsequently, cause alterations in the host metabolism. It is important to note that a limitation of the study is the difference in age between groups, given that age can impact the composition of microbiota.

Wolfram et al. (2002) [37] carried out the only reported study using a different Opuntia species. They analysed the effects of prickly pear pectin from Opuntia robusta on lipid and glucose metabolism. The investigation involved non-diabetic and non-obese males (37–55 years old), segmented into two groups: subjects with primary hypercholesterolemia (group A, n = 12) and those with combined hyperlipidaemia (group B, n = 12). The experimental period comprised an initial 8-week pre-running phase during which the volunteers followed a diet providing 7506 kJ (phase I). Subsequently, an additional eight weeks were included, wherein 625 kJ were replaced by prickly pear pulp (250 g/day) (phase II). The results revealed that the consumption of Opuntia robusta fruits induced a decrease in serum total cholesterol (−12%), LDL-cholesterol (−15%), apolipoprotein B (−9%), TG (−12%), fibrinogen (−11%), glucose (−11%), insulin (−11%) and uric acid (−10%). However, no changes were observed in body weight, cholesterol HDL, apolipoprotein A-I or lipoprotein levels. The hypocholesterolaemic action of Opuntia robusta may be partly explained by the presence of pectins in the Opuntia fruits.

Summary

With the exception of one work, all the reported clinical trials conducted in humans have utilised Opuntia ficus-indica, the most extensively studied Opuntia species. The primary products employed in these studies include cladode extracts, dehydrated cacti, or derivatives such as flour or plant fibres. Additionally, one published article has investigated Opuntia robusta, with a specific focus on the use of prickly pear pulp.

Concerning the studies involving Opuntia ficus-indica, it is noteworthy that reductions in parameters related to obesity, such as body weight, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference and fat mass, were observed only in certain instances, particularly those using a fibre extract or a cladode extract added to pasta. This observation underscores the significant influence of the experimental design on the outcomes. Furthermore, in several studies, certain prevalent obesity co-morbidities, such as hyperlipidemia and impaired glucose homeostasis control, have shown significant improvements. The beneficial effects on metabolic health do not consistently manifest in the same studies. Indeed, none of these works have conducted analyses to determine the mechanisms underlying the observed effects. In a particular study, the authors analysed the alterations induced by Opuntia supplementation in the composition of gut microbiota, but in fact, a definite causality with changes in other observed parameters has not been firmly established.

Regarding Opuntia robusta, it appears that the fruit pulp may be beneficial in managing some serum lipid alterations associated with obesity, although its efficacy in reducing body fat remains inconclusive. Nevertheless, only one study has been conducted with this Opuntia species, making it challenging to draw definite conclusions.

5. Conclusions

The data documented in the literature and compiled in the present review provide scientific evidence supporting the effect of Opuntia ficus-indica on obesity and some related metabolic disorders. Considering that published studies conducted in animal models have explored the effects of this plant in animals subjected to an obesogenic feeding pattern, wherein Opuntia ficus-indica products were administered concurrently with the obesogenic diet, the conclusion that can be drawn from these studies is that Opuntia ficus-indica has the potential to prevent obesity. Consequently, additional studies are warranted to assess its efficacy in the treatment of obesity. Nevertheless, there is a notable scarcity or lack of knowledge concerning crucial aspects. Thus, very limited information has been provided regarding the mechanisms of action underlying the observed effects. Conversely, the absence of a characterisation of the bioactive compound profile of Opuntia ficus-indica products means that information concerning the main molecules responsible for the observed effects is not available. Hence, it is crucial to undertake chemical characterisation to standardise the extracts that demonstrate beneficial effects on health. Moreover, it is important to precisely state which kind of product, whether cladode extract, fruit extract, fruit juice, etc., represents the optimal choice.

The effects observed in humans are not as straightforward as those found in animal models, with this discrepancy potentially arising from several reasons, including the inter-individual variability in humans compared to animals. In this line, in animal studies, all subjects within each experimental group typically exhibit similar characteristics, a circumstance that may not always be replicated in human subjects. For instance, in some studies, participants may be either overweight or obese, and the possibility of a differential response between these groups cannot be discarded. Moreover, when comparing various studies, the metabolic characteristics of the participants can vary significantly; thus, in some studies, volunteers may exhibit metabolic syndrome, while in others, they may not. In addition, a wide variety of Opuntia products has been used. As a result, further studies should be conducted across diverse population groups to enhance generalisability and understanding.

In summary, based on the existing scientific evidence, Opuntia, particularly Opuntia ficus-indica, emerges as a promising botanical resource for the development of products containing bioactive compounds that could prove beneficial in the management of obesity and its co-morbidities. Nevertheless, the existing knowledge is still limited, and further research is needed in both animal models and humans to conclusively determine whether it truly represents an effective tool for use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.P.P.; writing-original draft preparation I.G.-G., A.F.-Q., M.G., S.G.-Z., B.M., J.T. and M.P.P.; writing-reviewing and editing preparation I.G.-G., J.T. and M.P.P.; supervision M.P.P.; funding acquisition M.P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (PID2020-118300RB-C22) from MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe”, Government of the Basque Country (IT1482-22) and CIBEROBN (CB12/03/30007).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

Iker Gómez-García is a pre-doctoral fellowship from The University of the Basque Country funded by a doctoral fellowship from the Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Daniloski, D.; D’Cunha, N.M.; Speer, H.; McKune, A.J.; Alexopoulos, N.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Petkoska, A.T.; Naumovski, N. Recent Developments on Opuntia spp., their Bioactive Composition, Nutritional Values, and Health Effects. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Santillan, E.; Portillo-Reyes, J.; Madrigal-Bujaidar, E.; Sanchez-Gutierrez, M.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.; Delgado-Olivares, L.; Vargas-Mendoza, N.; Alvarez-Gonzalez, I.; Morales-Gonzalez, A.; et al. Opuntia spp. in Human Health: A Comprehensive Summary on its Pharmacological, Therapeutic and Preventive Properties. Part 2. Plants 2022, 11, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos Diaz, M.; Barba de la Rosa, A.-P.; Helies-Toussaint, C.; Gueraud, F.; Negre-Salvayre, A. Opuntia spp.: Characterization and Benefits in Chronic Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8634249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stintzing, F.C.; Carle, R. Cactus Stems (Opuntia spp.): A Review on their Chemistry, Technology, and Uses. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes de Araujo, F.; de Paulo Farias, D.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Underutilized Plants of the Cactaceae Family: Nutritional Aspects and Technological Applications. Food Chem. 2021, 362, 130196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavi, I. Ecosystem Services Related with Opuntia ficus-indica (Prickly Pear Cactus): A Review of Challenges and Opportunities. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 815–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Rodriguez, Y.; Martinez-Huelamo, M.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Ramirez, V.; Martinez-Taguena, N.; Trujillo, J. Ethnobotanical, Nutritional and Medicinal Properties of Mexican Drylands Cactaceae Fruits: Recent Findings and Research Opportunities. Food Chem. 2020, 312, 126073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouws, C.; Mortazavi, R.; Mellor, D.; McKune, A.; Naumovski, N. The Effects of Prickly Pear Fruit and Cladode (Opuntia spp.) Consumption on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 50, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouws, C.; Georgousopoulou, E.N.; Mellor, D.D.; McKune, A.; Naumovski, N. Effects of the Consumption of Prickly Pear Cacti (Opuntia spp.) and its Products on Blood Glucose Levels and Insulin: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2019, 55, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Ramos, S.; Avila-Nava, A.; Tovar, A.R.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Lopez-Romero, P.; Torres, N. Opuntia ficus indica (Nopal) Attenuates Hepatic Steatosis and Oxidative Stress in Obese Zucker (Fa/Fa) Rats. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1956–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Bejarano, P.I.; Gomez-Garcia, M.D.R.; Valverde, M.E.; Paredes-Lopez, O. Nopal (Opuntia spp.) and its Effects on Metabolic Syndrome: New Insights for the use of a Millenary Plant. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 3457–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besne-Eseverri, I.; Trepiana, J.; Gomez-Zorita, S.; Antunes-Ricardo, M.; Cano, M.P.; Portillo, M.P. Beneficial Effects of Opuntia spp. on Liver Health. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, P.; Abedimanesh, S.; Mesbah-Namin, S.A.; Ostadrahimi, A. Betalains, the Nature-Inspired Pigments, in Health and Diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 2949–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucini-Avendano, M.; Nicolas-Garcia, M.; Jimenez-Martinez, C.; Perea-Flores, M.J.; Gomez-Patino, M.B.; Arrieta-Baez, D.; Davila-Ortiz, G. Cladodes: Chemical and Structural Properties, Biological Activity, and Polyphenols Profile. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4007–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Lopez, I.; Lobo-Rodrigo, G.; Portillo, M.P.; Cano, M.P. Characterization, Stability, and Bioaccessibility of Betalain and Phenolic Compounds from Opuntia stricta Var. dillenii Fruits and Products of their Industrialization. Foods 2021, 10, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzur-Valdespino, S.; Arias-Rico, J.; Ramirez-Moreno, E.; Sanchez-Mata, M.C.; Jaramillo-Morales, O.A.; Angel-Garcia, J.; Zafra-Rojas, Q.Y.; Barrera-Galvez, R.; Cruz-Cansino, N.S. Applications and Pharmacological Properties of Cactus Pear (Opuntia spp.) Peel: A Review. Life 2022, 12, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruwa, C.E.; Amoo, S.O.; Kudanga, T. Opuntia (Cactaceae) Plant Compounds, Biological Activities and Prospects—A Comprehensive Review. Food Res. Int. 2018, 112, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héliès-Toussaint, C.; Fouché, E.; Naud, N.; Blas-Y-Estrada, F.; Del Socorro Santos-Diaz, M.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Barba de la Rosa, A.P.; Guéraud, F. Opuntia Cladode Powders Inhibit Adipogenesis in 3 T3-F442A Adipocytes and a High-Fat-Diet Rat Model by Modifying Metabolic Parameters and Favouring Faecal Fat Excretion. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboura, I.; Nani, A.; Belarbi, M.; Murtaza, B.; Fluckiger, A.; Dumont, A.; Benammar, C.; Tounsi, M.S.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Rialland, M.; et al. Protective Effects of Polyphenol-Rich Infusions from Carob (Ceratonia siliqua) Leaves and Cladodes of Opuntia Ficus-Indica Against Inflammation Associated with Diet-Induced Obesity and DSS-Induced Colitis in Swiss Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tapia, M.; Aguilar-López, M.; Pérez-Cruz, C.; Pichardo-Ontiveros, E.; Wang, M.; Donovan, S.M.; Tovar, A.R.; Torres, N. Nopal (Opuntia ficus indica) Protects from Metabolic Endotoxemia by Modifying Gut Microbiota in Obese Rats Fed High Fat/Sucrose Diet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiza-Martínez, M.V.; Martínez-Flores, H.E.; Guzmán-Quevedo, O.; Toscano, A.E.; Manhães de Castro, R.; Torner, L.; Mercado-Camargo, R.; Pérez-Sánchez, R.E.; Bartolome-Camacho, M.C. Addition of Opuntia ficus-indica Reduces Hypothalamic Microglial Activation and Improves Metabolic Alterations in Obese Mice Exposed to a High-Fat Diet. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 8, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekkal, H.; Harrat, N.e.I.; Affane, F.; Bensalah, F.; Louala, S.; Lamri-Senhadji, M. Cactus Young Cladodes Improves Unbalanced Glycemic Control, Dyslipidemia, Prooxidant/Antioxidant Stress Biomarkers and Stimulate Lecithin-Cholesterol Acyltransferase and Paraoxonase Activities in Young Rats After Cafeteria Diet Exposure. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 50, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas, Y.; Rios-Silva, M.; Huerta, M.; Lopez, M.; Bricio-Barrios, J.; Ortiz-Mesina, M.; Urzua, Z.; Saavedra-Molina, A.; Trujillo, X. The Comparative Effect of Nopal and Mucilage in Metabolic Parameters in Rats with a High-Fructose Diet. J. Med. Food 2019, 22, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounihi, A.; Bitam, A.; Bouazza, A.; Yargui, L.; Koceir, E.A. Fruit Vinegars Attenuate Cardiac Injury Via Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Adiposity Actions in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veron, H.E.; Gauffin Cano, P.; Fabersani, E.; Sanz, Y.; Isla, M.I.; Fernandez Espinar, M.T.; Gil Ponce, J.V.; Torres, S. Cactus Pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) Juice Fermented with Autochthonous Lactobacillus plantarum S-811. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Campos, R.; Meza-Rios, A.; Rodriguez-Sanabria, J.S.; la Rosa-Bibiano, R.D.; Corona-Cervantes, K.; Garcia-Mena, J.; Santos, A.; Sandoval-Rodriguez, A.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. Dietary Supplementation with Mexican Foods, Opuntia ficus indica, Theobroma cacao, and Acheta domesticus: Improving Obesogenic and Microbiota Features in Obese Mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 987222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, Y.; Variji, A.; Nosrati, M.; Khonakdar-Tarsi, A.; Kianmehr, A.; Kashi, Z.; Bahar, A.; Bagheri, A.; Mahrooz, A. Importance of Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) as an Antioxidant and Antiatherogenic Enzyme in the Cardiovascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes: Genotypic and Phenotypic Evaluation. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 161, 108067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, E.; Thimonier, C.; Degre, M. The Effect of NeOpuntia on Blood Lipid Parameters-Risk Factors for the Metabolic Syndrome (Syndrome X). Adv. Ther. 2007, 24, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, M.P.; Ewing, B.A.; Pischel, I.; Ziegler, A.; Benedek, B.; Feistel, B. Acute Blood Glucose Lowering Effects and Long-Term Safety of OpunDia Supplementation in Pre-Diabetic Males and Females. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grube, B.; Chong, P.; Lau, K.; Orzechowski, H. A Natural Fiber Complex Reduces Body Weight in the Overweight and Obese: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. Obesity 2013, 21, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grube, B.; Chong, P.; Alt, F.; Uebelhack, R. Weight Maintenance with Litramine (IQP-G-002AS): A 24-Week Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Study. J. Obes. 2015, 2015, 953138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignotti, G.; Hook, G.; Ghan, E.; Vega-López, S. Effect of Nopales (Opuntia spp.) on Lipoprotein Profile and Oxidative Stress among Moderately Hypercholesterolemic Adults: A Pilot Study. J. Funct. Foods. 2016, 27, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A.; Di Bona, D.; Candore, G.; Carru, C.; Zinellu, A.; Di Miceli, G.; Nicosia, A.; Gambino, C.M.; Ruisi, P.; Caruso, C.; et al. Targeting Aging with Functional Food: Pasta with Opuntia Single-Arm Pilot Study. Rejuvenation Res. 2018, 21, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglio, R.V.; Carruba, G.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Banach, M.; Patti, A.M.; Nikolic, D.; Cocciadiferro, L.; Zarcone, M.; Montalto, G.; Stoian, A.P.; et al. Pasta Supplemented with Opuntia ficus-indica Extract Improves Metabolic Parameters and Reduces Atherogenic Small Dense Low-Density Lipoproteins in Patients with Risk Factors for the Metabolic Syndrome: A Four-Week Intervention Study. Metabolites 2020, 10, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Murillo, M.E.; Cruz-Lopez, E.O.; Verde-Star, M.J.; Rivas-Morales, C.; Morales-Rubio, M.E.; Garza-Juarez, A.J.; Llaca-Diaz, J.M.; Ibarra-Salas, M.J. Consumption of Nopal Powder in Adult Women. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Cervantes, K.; Parra-Carriedo, A.; Hernandez-Quiroz, F.; Martinez-Castro, N.; Velez-Ixta, J.M.; Guajardo-Lopez, D.; Garcia-Mena, J.; Hernandez-Guerrero, C. Physical and Dietary Intervention with Opuntia ficus-indica (Nopal) in Women with Obesity Improves Health Condition through Gut Microbiota Adjustment. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, R.M.; Kritz, H.; Efthimiou, Y.; Stomatopoulos, J.; Sinzinger, H. Effect of Prickly Pear (Opuntia robusta) on Glucose- and Lipid-Metabolism in Non-Diabetics with Hyperlipidemia—A Pilot Study. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002, 114, 840–846. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).