Royal Jelly and Fermented Soy Extracts—A Holistic Approach to Menopausal Symptoms That Increase the Quality of Life in Pre- and Post-menopausal Women: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

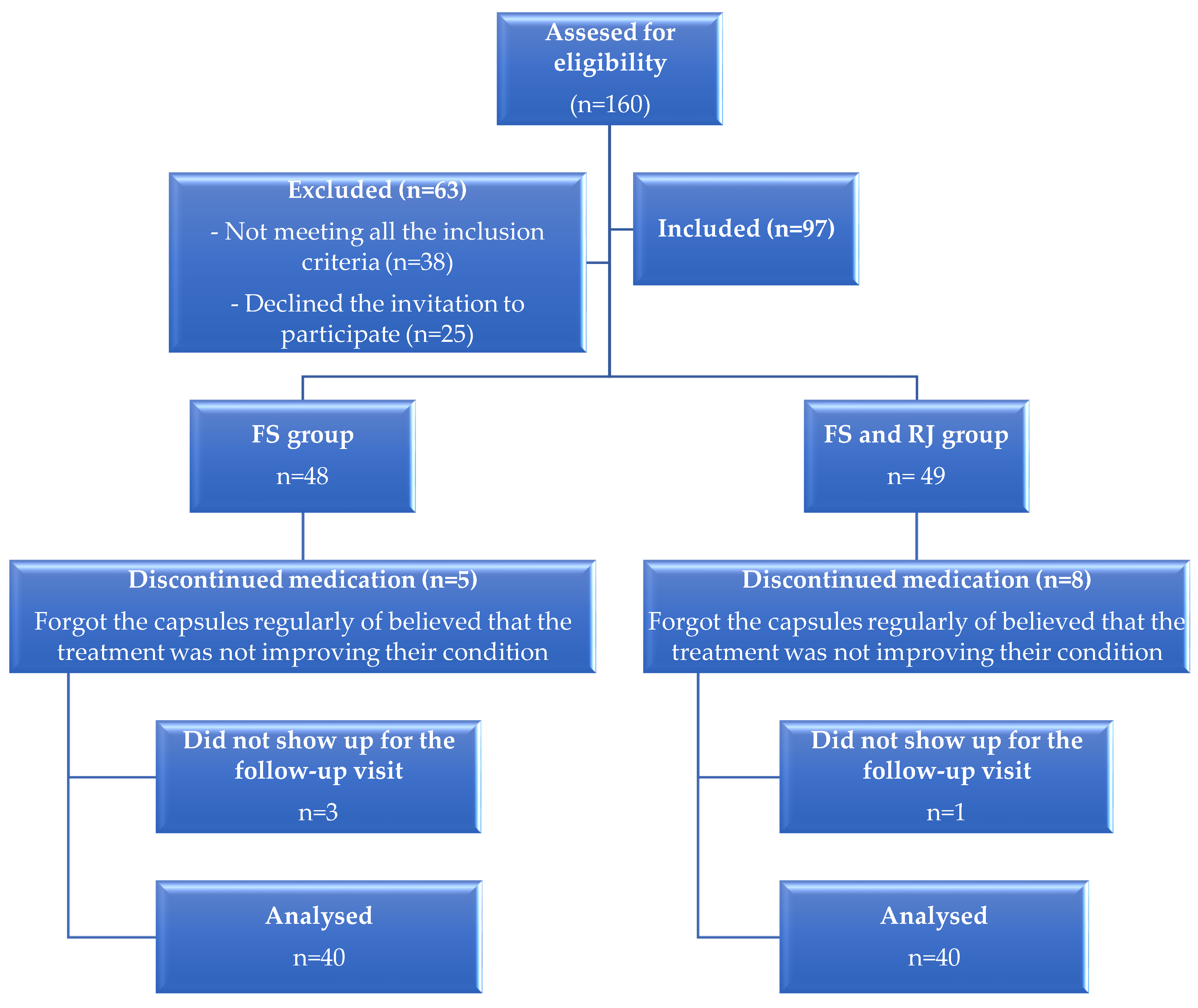

2.1. Participants and Methodology

- The inclusion criteria were:

- Mentally oriented women with menopausal symptoms (at least 3 hot flushes per day);

- Aged between 45 and 60 years;

- Able to read and write;

- Women free from any chronic treatments;

- Women who have received the above-mentioned indications of treatment from their physician for the management of menopausal symptoms.

- The exclusion criteria were:

- Women who received hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) or any other naturopathic treatments for the alleviation of menopause-related symptoms;

- Women who received other dietary supplements based on soy extracts or different doses of RJ;

- Women with chronic diseases (neoplasia, diabetes mellitus, and chronic hypertension);

- Women with psychiatric pathology;

- Women who refused to be included in this study.

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DASS-21 | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale |

| ER | Estrogen receptors |

| FS | Fermented soy |

| HDRS | Hamilton Depressive Rating Scale |

| MENQOL | Menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire |

| MRJP | Major royal jelly proteins |

| RJ | Royal jelly |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- McKinney, E.; Ashwill, J.; Murray, S.; James, S.; Gorrie, T.; Droske, S. Menopause, eds. In Maternal-Child Nursing; Elsevier Science Health Science Division: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2012; Volume 655. [Google Scholar]

- Prior, J.C. Perimenopause: The complex endocrinology of the menopausal transition. Endocr. Rev. 1998, 19, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, E.K.; Hofvind, S.; Byberg, L.; Eskild, A. The relation of age at menarche with age at natural menopause: A population study of 336 788 women in Norway. Human Reprod. 2018, 33, 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Chung, H.-F.; Dobson, A.J.; Pandeya, N.; Giles, G.G.; Bruinsma, F.; Brunner, E.J.; Kuh, D.; Hardy, R.; Avis, N.E.; et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: A pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e553–e564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, H.; Galal, A.F.; Rashed, A. Menopause in Egypt: Past and present perspectives. Climacteric 2006, 9, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hee, J.; MacNaughton, J.; Bangah, M.; Burger, H.G. Perimenopausal patterns of gonadotrophins, immunoreactive inhibin, oestradiol and progesterone. Maturitas 1993, 18, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.E.; Levine, K.B.; Kalilani, L.; Lewis, J.; Clark, R.V. Menopause-specific questionnaire assessment in US population-based study shows negative impact on health-related quality of life. Maturitas 2009, 62, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Lamadah, S.M.; Zamil, L.G.A. Quality of life among menopausal women. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. 2014, 3, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarev, D.; Finni, T.; Aukee, P.; Kokko, K.; Kujalav, U.; Kovanen, V.; Laakkonen, E.K.; Sipilä, S. Effect of the Menopausal Transition on Physical Performance: A Longitudinal Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, R.C.; Joffe, H. Vasomotor symptoms and menopause: Findings from the Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 38, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, K.; Sowers, M.; Crutchfield, M.; Wilson, A.; Jannausch, M. A longitudinal study of the predictors of prevalence and severity of symptoms commonly associated with menopause. Menopause 2005, 12, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, K.H.; Gill, S. Risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy: The evidence speaks. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2003, 168, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, E.; Gallus, S.; Bosetti, C.; Franceschi, S.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Hormone replacement therapy and cancer risk: A systematic analysis from a network of case-control studies. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 105, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moga, M.A.; Dimienescu, O.G.; Bălan, A.; Dima, L.; Toma, S.I.; Bîgiu, N.F.; Blidaru, A. Pharmacological and Therapeutic Properties of Punica granatum Phytochemicals: Possible Roles in Breast Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataman, H.; Aba, Y.A.; Dissiz, M.; Sevimli, S. Experiences Of Women In Turkey On Using Complementary And Alternative Medicine Methods Against The Symptoms Of Menopause: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Exp. Health Sci. 2020, 10, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, L.; Hicks, G.S.; Low, A.K.; Shepherd, J.M.; Brown, C.A. Phytoestrogens: A viable option? Am. J. Med. Sci. 2002, 324, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvejić, J.; Tepavčević, V.; Bursać, M.; Miladinović, J.; Malenčić, Đ. Isoflavone composition in F1 soybean progenies. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2698–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiari, L.; Piovesan, N.D.; Naoe, L.K.; José, I.C.; Viana, J.M.S.; Moreira, M.A.; de Barros, E.G. Genetic parameters relating isoflavone and protein content in soybean seeds. Euphytica 2004, 138, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villares, A.; Rostagno, M.A.; García-Lafuente, A.; Guillamón, E.; Martínez, J.A. Content and Profile of Isoflavones in Soy-Based Foods as a Function of the Production Process. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2011, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeja, W.; Grynkiewicz, G.; Rusin, A. Isoflavones, their Glycosides and Glycoconjugates. Synthesis and Biological Activity. Curr. Org. Chem. 2017, 21, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabich, M.; Materska, M. Biological Effect of Soy Isoflavones in the Prevention of Civilization Diseases. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-R.; Chen, K.-H. Utilization of Isoflavones in Soybeans for Women with Menopausal Syndrome: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Nef, S. Soy, phytoestrogens and metabolism: A review. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 304, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüser, S.; Guth, S.; Joost, H.G.; Soukup, S.T.; Köhrle, J.; Kreienbrock, L.; Diel, P.; Lachenmeier, D.W.; Eisenbrand, G.; Vollmer, G.; et al. Effects of isoflavones on breast tissue and the thyroid hormone system in humans: A comprehensive safety evaluation. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 2703–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvan, V.; Kalaivani, M.; Vijayakumar, A.; Sureshkumar, K.; Venkateskumar, K. Current knowledge and future direction of research on soy isoflavones as a therapeutic agents. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Kim, M.J.; Ahn, J.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.H.; Jang, Y.J.; Ha, T.Y.; Jung, C.H. Nutrikinetics of Isoflavone Metabolites After Fermented Soybean Product (Cheonggukjang) Ingestion in Ovariectomized Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1700322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Prado, F.G.; Pagnoncelli, M.G.B.; de Melo Pereira, G.V.; Karp, S.G.; Soccol, C.R. Fermented Soy Products and Their Potential Health Benefits: A Review. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welty, F.K.; Lee, K.S.; Lew, N.S.; Nasca, M.; Zhou, J.R. The association between soy nut consumption and decreased menopausal symptoms. J. Womens Health 2007, 16, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianke, L.; Mao, F.; Begna, D.; Yu, F.; Aijuan, Z. Proteome comparison of hypopharyngeal gland development between Italian and royal jelly producing worker honeybees (Apis mellifera L.). J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 6578–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunugi, H.; Mohammed Ali, A. Royal Jelly and Its Components Promote Healthy Aging and Longevity: From Animal Models to Humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A. Functional properties of honey, propolis, and royal jelly. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, R117–R124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya-Miyata, S.; Okamoto, I.; Ushio, S.; Iwaki, K.; Ikeda, M.; Kurimoto, M. Identification of a collagen production-promoting factor from an extract of royal jelly and its possible mechanism. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bălan, A.; Moga, M.A.; Dima, L.; Toma, S.; Elena Neculau, A.; Anastasiu, C.V. Royal Jelly-A Traditional and Natural Remedy for Postmenopausal Symptoms and Aging-Related Pathologies. Molecules 2020, 25, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asama, T.; Matsuzaki, H.; Fukushima, S.; Tatefuji, T.; Hashimoto, K.; Takeda, T. Royal Jelly Supplementation Improves Menopausal Symptoms Such as Backache, Low Back Pain, and Anxiety in Postmenopausal Japanese Women. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 4868412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taavoni, S.; Barkhordari, F.; Goushegir, A.; Haghani, H. Effect of Royal Jelly on premenstrual syndrome among Iranian medical sciences students: A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilditch, J.R.; Lewis, J.; Peter, A.; van Maris, B.; Ross, A.; Franssen, E.; Guyatt, G.H.; Norton, P.G.; Dunn, E. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. Maturitas 1996, 24, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.E.; Hilditch, J.R.; Wong, C.J. Further psychometric property development of the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life questionnaire and development of a modified version, MENQOL-Intervention questionnaire. Maturitas 2005, 50, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997, 314, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bener, A.; Alsulaiman, R.M.; Lg, D.; Hr, E. Comparison of Reliability and Validity of the Breast Cancer depression anxiety stress scales (DASS- 21) with the Beck Depression Inventory-(BDI-II) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Int. J. Behav. Res. Psychol. 2016, 4, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, S.B.; Beck, C.A.; Williams, J.V.A.; Barbui, C.; Metz, L.M. Major depression in multiple sclerosis. A population-based perspective. Neurology 2003, 61, 1524–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, C.; Tzitzika, M.; Bantis, A.; Nikolia, A.; Samarinas, M.; Kratiras, Z.; Thomas, C.; Skriapas, K. Female Sexual Dysfunction Among Greek Women With Multiple Sclerosis: Correlations With Organic and Psychological Factors. Sex. Med. 2019, 7, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedraui, P.; San Miguel, G.; Schwager, G. The effect of soy-derived isoflavones over hot flushes, menopausal symptoms and mood in climacteric women with increased body mass index. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2011, 27, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, P.; Young, R.L.; Steinberg, F.M.; Murray, M.J.; Lewis, R.D.; Cramer, M.A.; Barnes, S.; Ellis, K.J.; Shypailo, R.J.; Fraley, J.K.; et al. Effect of soy isoflavone supplementation on menopausal quality of life. Menopause 2013, 20, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.C.; Chan, A.S.Y.; Ho, Y.P.; So, E.K.F.; Sham, A.; Zee, B.; Woo, J.L.F. Effects of soy isoflavone supplementation on cognitive function in Chinese postmenopausal women: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Menopause 2007, 14, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Choue, R.; Lim, H. Effect of soy isoflavones supplement on climacteric symptoms, bone biomarkers, and quality of life in Korean postmenopausal women: A randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2017, 11, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.; Wegewitz, U.; Sommerfeld, C.; Grossklaus, R.; Lampen, A. Efficacy of isoflavones in relieving vasomotor menopausal symptoms—A systematic review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009, 53, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, B.; Vázquez, L.; Flórez, A.B. Equol: A Bacterial Metabolite from The Daidzein Isoflavone and Its Presumed Beneficial Health Effects. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setchell, K.D.; Brown, N.M.; Lydeking-Olsen, E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol—A clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3577–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aso, T.; Uchiyama, S.; Matsumura, Y.; Taguchi, M.; Nozaki, M.; Takamatsu, K.; Ishizuka, B.; Kubota, T.; Mizunuma, H.; Ohta, H. A Natural S-Equol Supplement Alleviates Hot Flushes and Other Menopausal Symptoms in Equol Nonproducing Postmenopausal Japanese Women. J. Women’s Health 2012, 21, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Borrego, R.; Mendoza, N.; Llaneza, P. A prospective study of DT56a (Femarelle®) for the treatment of menopause symptoms. Climacteric 2015, 18, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharif, S.N.; Darsareh, F. Effect of royal jelly on menopausal symptoms: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 37, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, C. Royal jelly boosts testosterone, estrogen, reduces menopause. J. Plant Med. Available online: https://plantmedicines.org/royal-jelly-testosterone-estrogen-menopause/ (accessed on 16 December 2023).

| Variable | FS Group (n.: 40) ± SD | FS and RJ Group (n.: 40) ± SD | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.67 ± 3.48 | 50 ± 3.47 | 0.267 |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 14 (35%) | 14 (35%) | 0.875 |

| Urban | 26 (65%) | 26 (65%) | |

| Menopausal stage | |||

| Menopausal transition | 14 (35%) | 17 (42.5%) | 0.362 |

| Post-menopause | 26 (65%) | 23 (57.5%) | |

| Type of menopause | |||

| Natural menopause | 33 (82.5%) | 32 (80%) | 0.346 |

| Surgically induced menopause | 7 (17.5%) | 8 (20%) | |

| BMI (body mass index) (kg/m2) | 28.54 ± 5.54 | 28.21 ± 5.31 | 0.953 |

| Normal weight | 13 (32.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | 0.656 |

| Overweight | 14 (35.0%) | 18 (45.0%) | |

| Grade I obesity | 9 (22.5%) | 6 (15.0%) | |

| Grade II obesity | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Grade III obesity | 3 (7.5%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Physical activity | |||

| No physical activity | 36 (90.0%) | 30 (75.0%) | 0.205 |

| >3 times/week | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| 1–3 times/week | 2 (5.0%) | 6 (15.0%) | |

| 1–3 times/month | 2 (5.0%) | 4 (10.0%) | |

| Alimentation | |||

| Normal diet | 32 (82.5%) | 32 (82.5%) | 0.885 |

| Vegetarian diet | 3 (7.5%) | 4 (10.0%) | |

| Diet based on dairy, eggs, and vegetables | 4 (10.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | |

| Dairy-free diet | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.5%) |

| Variable | FS Group (±SD) | FS and RJ Group (±SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| MENQOL score | 113.53 ± 39.05 | 111.30 ± 26.17 | 0.766 |

| Vasomotor domain | 16.83 ± 3.19 | 17.13 ± 5.67 | 0.724 |

| Psychosocial domain | 26.93 ± 10.00 | 26.98 ± 6.52 | 0.979 |

| Physical domain | 54.68 ± 18.07 | 53.20 ± 17.25 | 0.746 |

| Sexual domain | 15.35 ± 6.27 | 14.00 ± 5.93 | 0.326 |

| DASS-21 score | 17.50 ± 11.81 | 20.43 ± 10.70 | 0.249 |

| Depression score | 5.55 ± 4.18 | 6.33 ± 3.50 | 0.372 |

| Anxiety score | 6.30 ± 5.20 | 6.60 ± 3.76 | 0.768 |

| Stress score | 5.65 ± 3.74 | 7.50 ± 5.59 | 0.086 |

| Hot flushes (n./day) | 8.75 ± 3.82 | 7.18 ± 2.18 | 0.189 |

| Hot flushes intensity | |||

| Extremely weak (0) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.529 |

| Very weak (1) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Weak (2) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Mild (3) | 17 (42.5%) | 8 (20.0%) | |

| Intense (4) | 13 (32.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| Very intense (5) | 4 (10.0%) | 15 (37.5%) | |

| Extremely intense (6) | 6 (15.0%) | 3 (7.5%) |

| Variable | Baseline | Follow-Up Visit | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| MENQOL score | 113.53 ± 39.05 | 100.53 ± 38.56 | <0.001 |

| Vasomotor domain | 16.83 ± 4.30 | 11.25 ± 4.53 | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial domain | 26.93 ± 10.09 | 22.60 ± 9.25 | <0.001 |

| Physical domain | 54.68 ± 22.91 | 50.05 ± 22.50 | <0.001 |

| Sexual domain | 15.35 ± 6.27 | 14.75 ± 5.87 | <0.001 |

| DASS-21 score | 17.50 ± 11.81 | 14.05 ± 11.23 | <0.001 |

| Depression score | 5.55 ± 4.18 | 4.45 ± 3.96 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety score | 6.30 ± 5.20 | 4.72 ± 4.97 | <0.001 |

| Stress score | 5.65 ± 3.73 | 4.88 ± 3.43 | <0.001 |

| Hot flushes (n./day) | 8.75 ± 3.82 | 4.53 ± 3.79 | <0.001 |

| Hot flushes intensity | |||

| Extremely weak (0) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | <0.001 |

| Very weak (1) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (17.5%) | |

| Weak (2) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (30.0%) | |

| Mild (3) | 17 (42.5%) | 16 (40.0%) | |

| Intense (4) | 13 (32.5%) | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Very intense (5) | 4 (10%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Extremely intense (6) | 6 (15%) | 2 (5.0%) |

| Variable | Baseline | Follow-Up Visit | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| MENQOL score | 111.30 ± 26.17 | 80.08 ± 28.05 | <0.001 |

| Vasomotor domain | 17.13 ± 3.19 | 8.15 ± 3.20 | <0.001 |

| Psychosocial domain | 26.98 ± 6.52 | 18.43 ± 7.09 | <0.001 |

| Physical domain | 53.20 ± 17.25 | 40.42 ± 18.86 | <0.001 |

| Sexual domain | 14.00 ± 5.93 | 12.90 ± 5.57 | <0.001 |

| DASS-21 score | 20.43 ± 10.70 | 16.05 ± 10.07 | <0.001 |

| Depression score | 6.33 ± 3.50 | 4.6 ± 3.01 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety score | 6.60 ± 3.76 | 4.95 ± 3.61 | <0.001 |

| Stress score | 7.50 ± 5.59 | 6.48 ± 5.19 | <0.001 |

| Hot flushes (n./day) | 7.18 ± 2.18 | 2.85 ± 1.27 | <0.001 |

| Hot flushes intensity | |||

| Extremely weak (0) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (12.5%) | <0.001 |

| Very weak (1) | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (20.0%) | |

| Weak (2) | 1 (2.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Mild (3) | 8 (20%) | 16 (40%) | |

| Intense (4) | 13 (32.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Very intense (5) | 15 (37.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Extremely intense (6) | 3 (7.5%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Variable | FS Group | FS and RJ Group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| MENQOL score | 100.53 ± 38.56 | 80.08 ± 28.05 | 0.008 |

| Vasomotor domain | 11.25 ± 4.53 | 8.15 ± 3.20 | 0.001 |

| Psychosocial domain | 22.60 ± 9.25 | 18.43 ± 7.09 | 0.026 |

| Physical domain | 50.05 ± 22.50 | 40.42 ± 18.86 | 0.041 |

| Sexual domain | 14.75 ± 5.87 | 12.90 ± 5.57 | 0.153 |

| DASS-21 score | 14.05 ± 11.23 | 16.05 ± 10.07 | 0.404 |

| Depression score | 4.45 ± 3.96 | 4.6 ± 3.01 | 0.849 |

| Anxiety score | 4.72 ± 4.97 | 4.95 ± 3.61 | 0.818 |

| Stress score | 4.88 ± 3.43 | 6.48 ± 5.19 | 0.108 |

| Hot flushes (n./day) | 4.53 ± 3.79 | 2.85 ± 1.27 | 0.011 |

| Hot flushes intensity | |||

| Extremely weak (0) | 2 (5.0%) | 5 (12.5%) | 0.465 |

| Very weak (1) | 7 (17.5%) | 8 (20.0%) | |

| Weak (2) | 12 (30.0%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Mild (3) | 16 (40.0%) | 16 (40.0%) | |

| Intense (4) | 1 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Very intense (5) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Extremely intense (6) | 2 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balan, A.; Moga, M.A.; Neculau, A.E.; Mitrica, M.; Rogozea, L.; Ifteni, P.; Dima, L. Royal Jelly and Fermented Soy Extracts—A Holistic Approach to Menopausal Symptoms That Increase the Quality of Life in Pre- and Post-menopausal Women: An Observational Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050649

Balan A, Moga MA, Neculau AE, Mitrica M, Rogozea L, Ifteni P, Dima L. Royal Jelly and Fermented Soy Extracts—A Holistic Approach to Menopausal Symptoms That Increase the Quality of Life in Pre- and Post-menopausal Women: An Observational Study. Nutrients. 2024; 16(5):649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050649

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalan, Andreea, Marius Alexandru Moga, Andrea Elena Neculau, Maria Mitrica, Liliana Rogozea, Petru Ifteni, and Lorena Dima. 2024. "Royal Jelly and Fermented Soy Extracts—A Holistic Approach to Menopausal Symptoms That Increase the Quality of Life in Pre- and Post-menopausal Women: An Observational Study" Nutrients 16, no. 5: 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050649

APA StyleBalan, A., Moga, M. A., Neculau, A. E., Mitrica, M., Rogozea, L., Ifteni, P., & Dima, L. (2024). Royal Jelly and Fermented Soy Extracts—A Holistic Approach to Menopausal Symptoms That Increase the Quality of Life in Pre- and Post-menopausal Women: An Observational Study. Nutrients, 16(5), 649. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050649