Does Online Social Support Affect the Eating Behaviors of Polish Women with Insulin Resistance?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Consent of the Bioethics Committee

2.2. Characteristics of the Study Population

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Age between 18 and 65 years;

- Insulin resistance (disorder diagnosed by a physician in the past);

- Current good health.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- All chronic diseases and condition, including the following:

- ○

- Heart;

- ○

- Liver;

- ○

- Kidney;

- ○

- Pancreas diseases;

- ○

- Autoimmune diseases;

- ○

- Metabolic diseases;

- ○

- Inflammatory bowel disease;

- ○

- Type 2 diabetes.

- ○

- Exceptions: secondary hypercholesterolemia; secondary arterial hypertension; Pregnancy and breastfeeding; Previous or ongoing cancer; Pharmacotherapy (exceptions: hormonal contraception, metformin used in the treatment of PCOS); Mental disorders, including eating disorders; Acute inflammatory disease.

2.5. Research Model

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristic

3.2. Anthropometric Parameters

3.3. Financial Situation

3.4. The Household’s Situation

3.5. Education Level

3.6. Occupation

3.7. Medical Care

3.8. Dietitian Care

3.9. Self-Assessment of Eating Behavior

3.10. Membership in Support Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olatunbosun, S.T. Insulin Resistance, Medscape. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/122501-overview?form=fpf (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Cetin, E.G.; Demir, N.; Sen, I. The Relationship between Insulin Resistance and Liver Damage in non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Patients. Med. Bull. Sisli Etfal Hosp. 2020, 54, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmol, J.M.; Carlsson, M.; Raun, S.H.; Grand, M.K.; Sorensen, J.; Lang Lehrskov, L.; Richter, E.A.; Norgaard, O.; Sylow, L. Insulin resistance in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Oncol. 2023, 62, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, X.; Nie, X.; He, B. Insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome across various tissues: An updated review of pathogenesis, evaluation, and treatment. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- da Silva, A.A.; do Carmo, J.M.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Mouton, A.J.; Hall, J.E. Role of Hyperinsulinemia and Insulin Resistance in Hypertension: Metabolic Syndrome Revisited. Can. J. Cardiol. 2020, 36, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1149239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 3. Prevention or Delay of Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47 (Suppl. 1), S43–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evert, A.B.; Dennison, M.; Gardner, C.D.; Garvey, W.T.; Lau, K.H.K.; MacLeod, J.; Mitri, J.; Pereira, R.F.; Rawlings, K.; Robinson, S.; et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bacquer, D.; Astin, F.; Kotseva, K.; Pogosova, N.; De Smedt, D.; De Backer, G.; Rydén, L.; Wood, D.; Jennings, C.; EUROASPIRE IV and V surveys of the European Observational Research Programme of the European Society of Cardiology. Poor adherence to lifestyle recommendations in patients with coronary heart disease: Results from the EUROASPIRE surveys. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, E.; Hassmén, P.; Pumpa, K.L. Determinants of adherence to lifestyle intervention in adults with obesity: A systematic review. Clin. Obes. 2017, 7, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating Positive Health Behaviors and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47 (Suppl. 1), S77–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumuk, V.; Frühbeck, G.; Oppert, J.M.; Woodward, E.; Toplak, H. An EASO position statement on multidisciplinary obesity management in adults. Obes. Facts. 2014, 7, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. The Primacy of Self-Regulation in Health Promotion. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 54, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gawęcki, J.; Wądołowska, L.; Czarnocińska, J.; Galiński, G.; Kołłajtis-Dołowy, A.; Roszkowski, W.; Wawrzyniak, A.; Przybyłowicz, K.; Krusińska, B.; et al. Questionnaire for the study of views and dietary habits for people aged 16 to 65, version 1.1—Questionnaire administered by the interviewer-researcher. Chapter 1. In Questionnaire for the Study of Views and Dietary Habits and the Procedure for Data Development; Gawęcki, J., Ed.; Publishing House of the Committee on Human Nutrition, Polish Academy of Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrant, M.; Khan, S.S.; Farrow, C.V.; Shah, P.; Daly, M.; Kos, K. Patient experiences of a bariatric group program for managing obesity: A qualitative interview study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, U.; Pischke, C.R.; Weidner, G.; Daubenmier, J.; Elliot-Eller, M.; Scherwitz, L.; Bullinger, M.; Ornish, D. Social support group attendance is related to blood pressure, health behaviors, and quality of life in the Multicenter Lifestyle Demonstration Project. Psychol. Health Med. 2008, 13, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Support Groups: Make Connections and Get Help. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/support-groups/art-20044655 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Griffiths, K.M.; Calear, A.L.; Banfield, M.; Tam, A. Systematic review on Internet Support Groups (ISGs) and depression (2): What is known about depression ISGs? J. Med. Internet Res. 2009, 11, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gallant, M.P. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: A review and directions for research. Health Educ. Behav. 2003, 30, 170–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, J.; Thorburn, S.; Sinky, T. Exploring healthcare experiences among online interactive weight loss forum users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 57, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.C.; Miles, L.M.; Hawkes, R.E.; French, D.P. Experiences of online group support for engaging and supporting participants in the National Health Service Digital Diabetes Prevention Programme: A qualitative interview study. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2024, 29, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huh, J.; McDonald, D.W.; Hartzler, A.; Pratt, W. Patient moderator interaction in online health communities. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2013, 2013, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hwang, K.O.; Ottenbacher, A.J.; Green, A.P.; Cannon-Diehl, M.R.; Richardson, O.; Bernstam, E.V.; Thomas, E.J. Social support in an Internet weight loss community. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reading, J.M.; Buhr, K.J.; Stuckey, H.L. Social Experiences of Adults Using Online Support Forums to Lose Weight: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46 (Suppl. 2), 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, M.T.; Bak, C.K.; Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.; Riddersholm, S.J.; Skals, R.K.; Mortensen, R.N.; Maindal, H.T.; Bøggild, H.; Nielsen, G.; et al. Associations of health literacy with socioeconomic position, health risk behavior, and health status: A large national population-based survey among Danish adults. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garcia-Codina, O.; Juvinyà-Canal, D.; Amil-Bujan, P.; Bertran-Noguer, C.; González-Mestre, M.A.; Masachs-Fatjo, E.; Santaeugènia, S.J.; Magrinyà-Rull, P.; Saltó-Cerezuela, E. Determinants of health literacy in the general population: Results of the Catalan health survey. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aaby, A.; Friis, K.; Christensen, B.; Rowlands, G.; Maindal, H.T. Health literacy is associated with health behavior and self-reported health: A large population-based study in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1880–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Elements | Total = 1565 (%) | With Support Group = 1011 (%) | Without Support Group = 554 (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.65 ± 8.07 | 35.26 ± 8.03 | 33.53 ± 8.03 | <0.0001 a |

| Weight [kg] | 81.80 ± 19.20 | 83.21 ± 19.23 | 79.22 ± 18.89 | <0.0001 a |

| Waist circumference [cm] | 96.02 ± 16.01 | 96.80 ± 15.12 | 94.45 ± 17.57 | 0.0266 a |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 29.70 ± 8.56 | 30.10 ± 7.52 | 28.99 ± 10.15 | 0.0001 a |

| Place of residence | ||||

| Village | 323 (20.6) | 186 (18) | 137 (25) | 0.0242 d |

| City under 20,000 inhabitants | 178 (11.4) | 123 (12) | 55 (10) | |

| City from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants | 330 (21.1) | 217 (21) | 113 (200 | |

| City over 100,000 inhabitants | 734 (46.9) | 485 (48) | 249 (45) | |

| Financial situation | ||||

| Above average | 319 (20.4) | 196 (19) | 123 (22) | ns d |

| Average | 1138 (72.7) | 747 (74) | 391 (71) | |

| Under average | 108 (6.9) | 68 (7) | 40 (7) | |

| The household’s situation | ||||

| We live very well—we can afford some luxury | 77 (4.9) | 45 (4) | 32 (5.5) | 0.0036 d |

| We live well—we have enough for a lot without saving much | 720 (46) | 451 (45) | 269 (48.5) | |

| We live on average—we have enough for everyday life. but we have to save for more serious purchases | 695 (44.4) | 478 (47) | 217 (39) | |

| We live modestly—we have to be very frugal daily | 66 (4.2) | 35 (3.5) | 31 (6) | |

| We live very poor—we don’t even have enough for our basic needs | 7 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (1) | |

| Occupation | ||||

| No, I am retired or on a disability pension | 17 (1.1) | 12 (1) | 5 (1) | 0.0058 d |

| No, I am on parental leave, I am unemployed, I run the house | 163 (10.4) | 122 (12) | 41 (7.5) | |

| No, I am studying or learning | 113 (7.2) | 61 (6) | 52 (9.5) | |

| Yes, but I work part-time | 93 (5.9) | 55 (5.5) | 38 (7) | |

| Yes, I have permanent employment | 1179 (75.3) | 761 (75.5) | 418 (75) | |

| Education level | ||||

| Higher | 1169 (74.7) | 765 (76) | 404 (73) | 0.3450 d |

| Secondary | 362 (23.1) | 225 (22) | 137 (25) | |

| Basic vocational | 23 (1.5) | 16 (1.5) | 7 (1) | |

| Primary | 11 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 6 (1) | |

| Medical care | ||||

| Yes | 1332 (85.1) | 874 (86) | 458 (83) | 0.0447 d |

| No | 233 (14.9) | 137 (14) | 96 (17) | |

| Dietitian care | ||||

| Yes | 1183 (75.6) | 749 (74) | 434 (78.5) | ns d |

| No | 382 (24.4) | 262 (26) | 120 (21.5) | |

| Self-assessment of nutrition knowledge | ||||

| Insufficient | 226 (14) | 128 (13) | 98 (18) | 0.0013 d |

| Sufficient | 593 (38) | 372 (37) | 221 (40) | |

| Good | 576 (37) | 405 (40) | 171 (30) | |

| Very good | 170 (11) | 106 (10) | 64 (12) | |

| Self-assessment of eating behavior | ||||

| Very bad | 55 (4) | 36 (3) | 19 (3.5) | ns d |

| Bad | 524 (33) | 323 (32) | 201 (36) | |

| Good | 914 (58) | 603 (60) | 311 (56) | |

| Very good | 72 (5) | 49 (5) | 23 (4.5) | |

| Diet Indexes | ||||

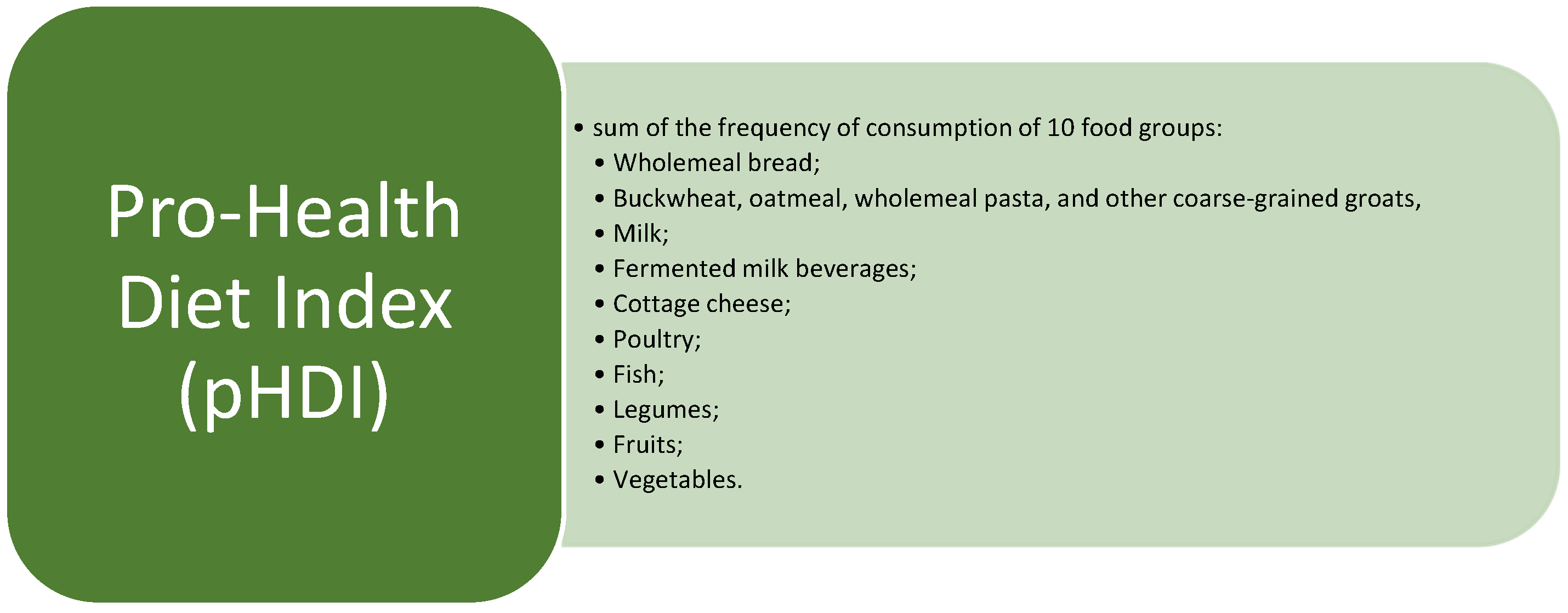

| pHDI | 5.06 ± 2.68 | 5.18 ± 2.69 | 4.86 ± 2.69 | 0.0319 a |

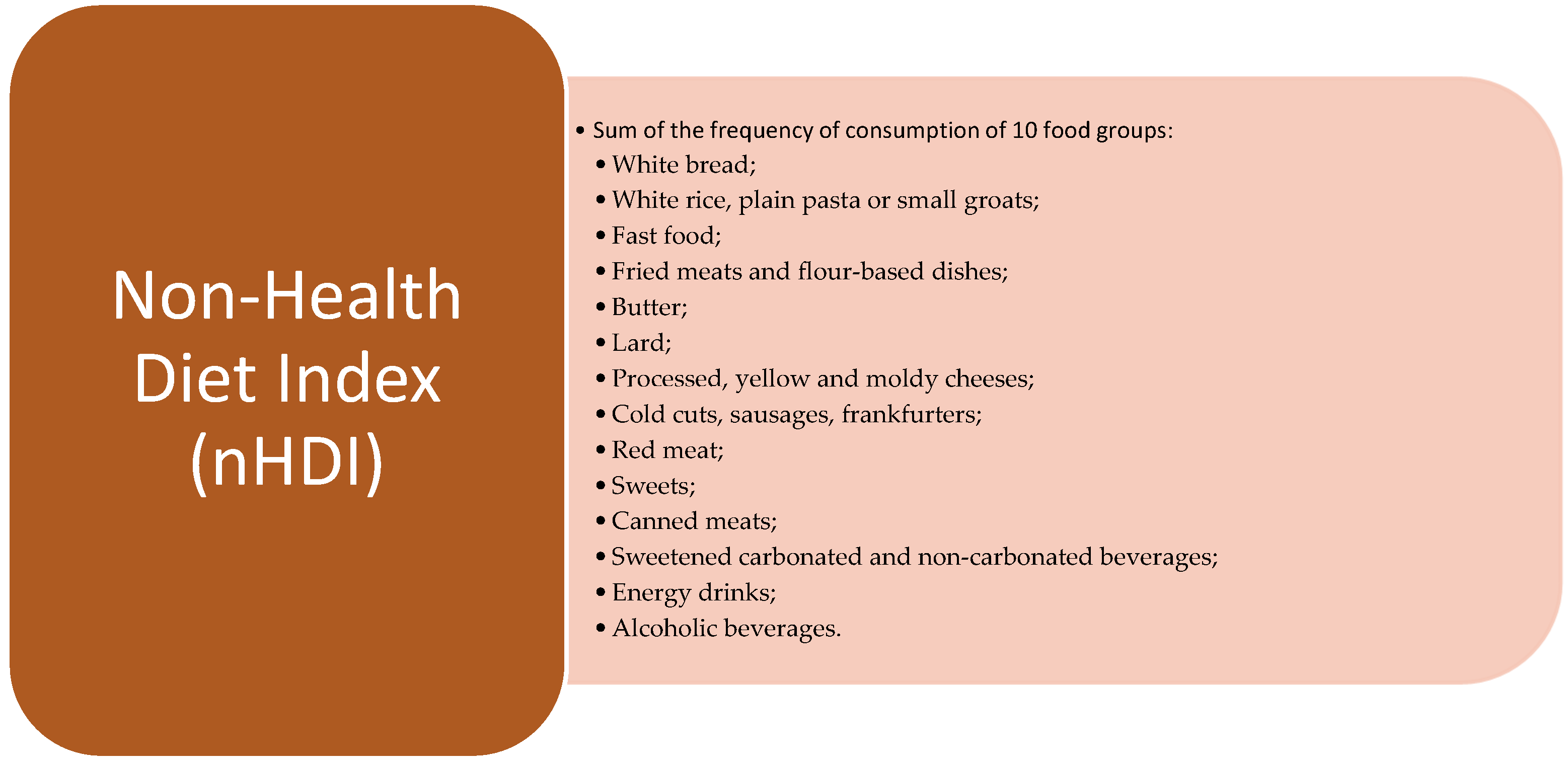

| nHDI | 3.20 ± 2.17 | 3.15 ± 2.17 | 3.27 ± 2.17 | ns a |

| Total | With Support Group | Without Support Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | p | R | p | R | p | |

| pHDI | ||||||

| Body mass [kg] | −0.10 | 0.0001 c | −0.09 | 0.0040 c | −0.12 | 0.0035 c |

| BMI [kg/m2] | −0.09 | 0.0002 c | −0.09 | 0.0047 c | −0.12 | 0.0044 c |

| Waist circumferences [cm] | −0.12 | <0.0001 c | −0.12 | 0.0014 c | −0.15 | 0.0047 c |

| nHDI | ||||||

| Body mass [kg] | 0.06 | 0.0285 c | 0.03 | ns c | 0.11 | 0.0120 c |

| BMI [kg/m2] | 0.07 | 0.0088 c | 0.04 | ns c | 0.12 | 0.0041 c |

| Waist circumferences [cm] | 0.08 | 0.0050 c | 0.06 | ns c | 0.14 | 0.0056 c |

| Total = 1565 (%) | With Support Group = 1011 (%) | Without Support Group = 554 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | |||

| Village | 5.14 ± 2.72 | 5.33 ± 2.66 | 4.89 ± 2.78 |

| City under 20,000 inhabitants | 5.03 ± 2.87 | 5.07 ± 2.94 | 4.94 ± 2.72 |

| City from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants | 4.78 ± 2.69 | 4.88 ± 2.68 | 4.58 ± 2.71 |

| City over 100,000 inhabitants | 5.17 ± 2.6 | 5.28 ± 2.63 | 4.95 ± 2.52 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Financial situation | |||

| Above average | 5.33 ± 2.58 | 5.5 ± 2.62 | 5.08 ± 2.5 |

| Average | 5.03 ± 2.66 | 5.15 ± 2.66 | 4.82 ± 2.64 |

| Under average | 4.58 ± 3.07 | 4.58 ± 3.08 | 4.57 ± 3.09 |

| p | 0.011 b | 0.0185 b | ns b |

| The household’s situation | |||

| Very well | 5.35 ± 3.01 | 5.51 ± 3.08 | 5.14 ± 2.94 |

| Well | 5.18 ± 2.54 | 5.27 ± 2.56 | 5.04 ± 2.52 |

| On average | 5.01 ± 2.73 | 5.15 ± 2.72 | 4.7 ± 2.73 |

| Modestly | 4.15 ± 3.0 | 3.97 ± 3.16 | 4.37 ± 2.85 |

| Very poor | 3.5 ± 2.22 | 4.54 ± 3.96 | 3.08 ± 1.64 |

| p | 0.0092 b | 0.0399 b | ns b |

| Occupation | |||

| Retired or on a disability pension | 3.35 ± 2.33 | 3.69 ± 2.08 | 2.87 ± 3.03 |

| Parental leave, unemployed, running the house | 5.32 ± 2.82 | 5.16 ± 2.67 | 5.78 ± 3.2 |

| Studying or learning | 5.6 ± 2.35 | 5.57 ± 2.36 | 5.63 ± 2.37 |

| Working part-time | 4.88 ± 2.57 | 5.56 ± 2.39 | 3.91 ± 2.55 |

| Permanent employment | 5.01 ± 2.69 | 5.14 ± 2.74 | 4.78 ± 2.58 |

| p | 0.005 b | ns b | 0.0016 b |

| Education level | |||

| Higher | 5.16 ± 2.64 | 5.33 ± 2.67 | 4.85 ± 2.55 |

| Secondary | 4.86 ± 2.74 | 4.77 ± 2.68 | 5.0 ± 2.85 |

| Basic vocational | 3.73 ± 3.2 | 3.89 ± 3.28 | 3.35 ± 3.24 |

| Primary | 4.04 ± 2.53 | 4.29 ± 1.92 | 3.84 ± 3.12 |

| p | ns b | 0.0092 b | ns b |

| Medical care | |||

| Yes | 5.04 ± 2.70 | 5.24 ± 2.69 | 5.01 ± 2.63 |

| No | 4.51 ± 2.53 | 4.78 ± 2.7 | 4.16 ± 2.62 |

| p | ns a | ns a | 0.0071 a |

| Dietitian care | |||

| Yes | 5.58 ± 2.62 | 5.7 ± 2.71 | 5.31 ± 2.4 |

| No | 4.9 ± 2.68 | 4.99 ± 2.66 | 4.74 ± 2.7 |

| p | <0.0001 a | 0.0004 a | 0.0151 a |

| Self-assessment of nutrition knowledge | |||

| Insufficient | 5.12 ± 2.68 | 5.13 ± 2.94 | 5.1 ± 2.3 |

| Sufficient | 5.04 ± 2.64 | 5 ± 2.6 | 5.1 ± 2.7 |

| Good | 5.01 ± 2.72 | 4.86 ± 2.73 | 5.37 ± 2.67 |

| Very good | 5.25 ± 2.68 | 5.12 ± 2.87 | 5.46 ± 2.36 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Self-assessment of eating behavior | |||

| Very bad | 4.88 ± 2.56 | 5.33 ± 2.64 | 4.02 ± 2.23 |

| Bad | 5.09 ± 2.61 | 4.94 ± 2.59 | 5.32 ± 2.65 |

| Good | 5.06 ± 2.73 | 4.98 ± 2.81 | 5.23 ± 2.58 |

| Very good | 5.05 ± 2.55 | 4.89 ± 2.68 | 5.39 ± 2.25 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Total (Mean ± SD) | With Support Group (Mean ± SD) | Without a Support Group (Mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Place of residence | |||

| Village | 3.45 ± 2.72 | 3.45 ± 2.61 | 4.89 ± 2.78 |

| City under 20,000 inhabitants | 5.03 ± 2.87 | 3.36 ± 2.35 | 3.65 ± 2.04 |

| City from 20,000 to 100,000 inhabitants | 4.78 ± 2.69 | 3.07 ± 2.39 | 3.36 ± 2.78 |

| City over 100,000 inhabitants | 5.17 ± 2.6 | 3.02 ± 1.79 | 3.05 ± 1.85 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Financial situation | |||

| Above average | 3.06 ± 1.88 | 3.07 ± 1.85 | 3.04 ± 1.93 |

| Average | 3.19 ± 2.17 | 3.11 ± 2.12 | 3.35 ± 2.27 |

| Under average | 3.67 ± 2.76 | 3.89 ± 3.16 | 3.30 ± 1.9 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| The household’s situation | |||

| Very well | 3.36 ± 1.77 | 3.54 ± 1.68 | 3.12 ± 1.89 |

| Well | 3.09 ± 1.96 | 2.99 ± 1.9 | 3.27 ± 2.04 |

| On average | 3.25 ± 2.26 | 3.26 ± 2.34 | 3.22 ± 2.07 |

| Modestly | 3.53 ± 3.48 | 3.32 ± 3.2 | 3.78 ± 3.81 |

| Very poor | 3.29 ± 1.33 | 2.26 ± 0.54 | 3.7 ± 1.36 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Occupation | |||

| Retired or on a disability pension | 2.2 ± 1.57 | 2.18 ± 1.42 | 2.26 ± 2.07 |

| Parental leave, unemployed, running the house | 3.44 ± 2.72 | 3.33 ± 2.44 | 3.77 ± 3.43 |

| Studying or learning | 3.9 ± 2.76 | 4.19 ± 3.17 | 3.56 ± 2.18 |

| Working part-time | 3.14 ± 2.29 | 3.24 ± 2.69 | 3.0 ± 1.56 |

| Permanent employment | 3.11 ± 1.99 | 3.05 ± 1.96 | 3.23 ± 2.06 |

| p | 0.0059 b | 0.0127 b | ns b |

| Education level | |||

| Higher | 3.16 ± 1.99 | 3.11 ± 1.92 | 3.27 ± 2.1 |

| Secondary | 3.27 ± 2.41 | 3.23 ± 2.43 | 3.33 ± 2.38 |

| Basic vocational | 2.86 ± 3.79 | 3.24 ± 4.43 | 2.01 ± 1.54 |

| Primary | 4.94 ± 5.43 | 6.13 ± 8.04 | 3.94 ± 2.14 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Medical care | |||

| Yes | 3.18 ± 2.13 | 3.04 ± 2.0 | 3.27 ± 2.15 |

| No | 3.39 ± 2.35 | 3.88 ± 2.92 | 3.29 ± 2.3 |

| p | ns a | 0.0006 a | ns a |

| Dietitian care | |||

| Yes | 3.18 ± 2.13 | 3.03 ± 2.10 | 3.63 ± 2.66 |

| No | 3.29 ± 2.35 | 2.98 ± 1.89 | 3.54 ± 2.49 |

| p | ns a | ns a | ns a |

| Self-assessment of nutrition knowledge | |||

| Insufficient | 3.48 ± 2.73 | 2.89 ± 2.17 | 3.34 ± 1.89 |

| Sufficient | 3.29 ± 2.26 | 3.04 ± 1.94 | 3.55 ± 2.89 |

| Good | 3.03 ± 1.83 | 2.98 ± 1.90 | 3.81 ± 2.39 |

| Very good | 3.03 ± 1.83 | 3.05 ± 1.89 | 3.24 ± 1.94 |

| p | ns b | ns b | ns b |

| Self-assessment of eating behavior | |||

| Very bad | 4.54 ± 3.64 | 3.76 ± 2.65 | 2.39 ± 1.01 |

| Bad | 3.89 ± 2.51 | 3.06 ± 2.04 | 3.46 ± 2.13 |

| Good | 2.77 ± 1.6 | 2.91 ± 1.84 | 3.60 ± 2.72 |

| Very good | 2.51 ± 2.48 | 3.20 ± 1.83 | 4.76 ± 2.51 |

| p | <0.0001 b | ns b | 0.0101 b |

| Membership in Support Group | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| pHDI | |

| Yes | 5.18 ± 2.69 |

| No | 4.86 ± 2.64 |

| p | 0.0319 a |

| nHDI | |

| Yes | 3.15 ± 2.17 |

| No | 3.27 ± 2.17 |

| p | ns a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pastusiak, K.M.; Kręgielska-Narożna, M.; Mróz, M.; Seraszek-Jaros, A.; Błażejewska, W.; Bogdański, P. Does Online Social Support Affect the Eating Behaviors of Polish Women with Insulin Resistance? Nutrients 2024, 16, 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203509

Pastusiak KM, Kręgielska-Narożna M, Mróz M, Seraszek-Jaros A, Błażejewska W, Bogdański P. Does Online Social Support Affect the Eating Behaviors of Polish Women with Insulin Resistance? Nutrients. 2024; 16(20):3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203509

Chicago/Turabian StylePastusiak, Katarzyna Magdalena, Matylda Kręgielska-Narożna, Michalina Mróz, Agnieszka Seraszek-Jaros, Wiktoria Błażejewska, and Paweł Bogdański. 2024. "Does Online Social Support Affect the Eating Behaviors of Polish Women with Insulin Resistance?" Nutrients 16, no. 20: 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203509

APA StylePastusiak, K. M., Kręgielska-Narożna, M., Mróz, M., Seraszek-Jaros, A., Błażejewska, W., & Bogdański, P. (2024). Does Online Social Support Affect the Eating Behaviors of Polish Women with Insulin Resistance? Nutrients, 16(20), 3509. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16203509