Opportunities and Challenges of California’s Fruit and Vegetable Electronic Benefit Transfer Pilot Project at Farmers’ Markets: A Qualitative Study with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Shoppers and Farmers’ Market Staff

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

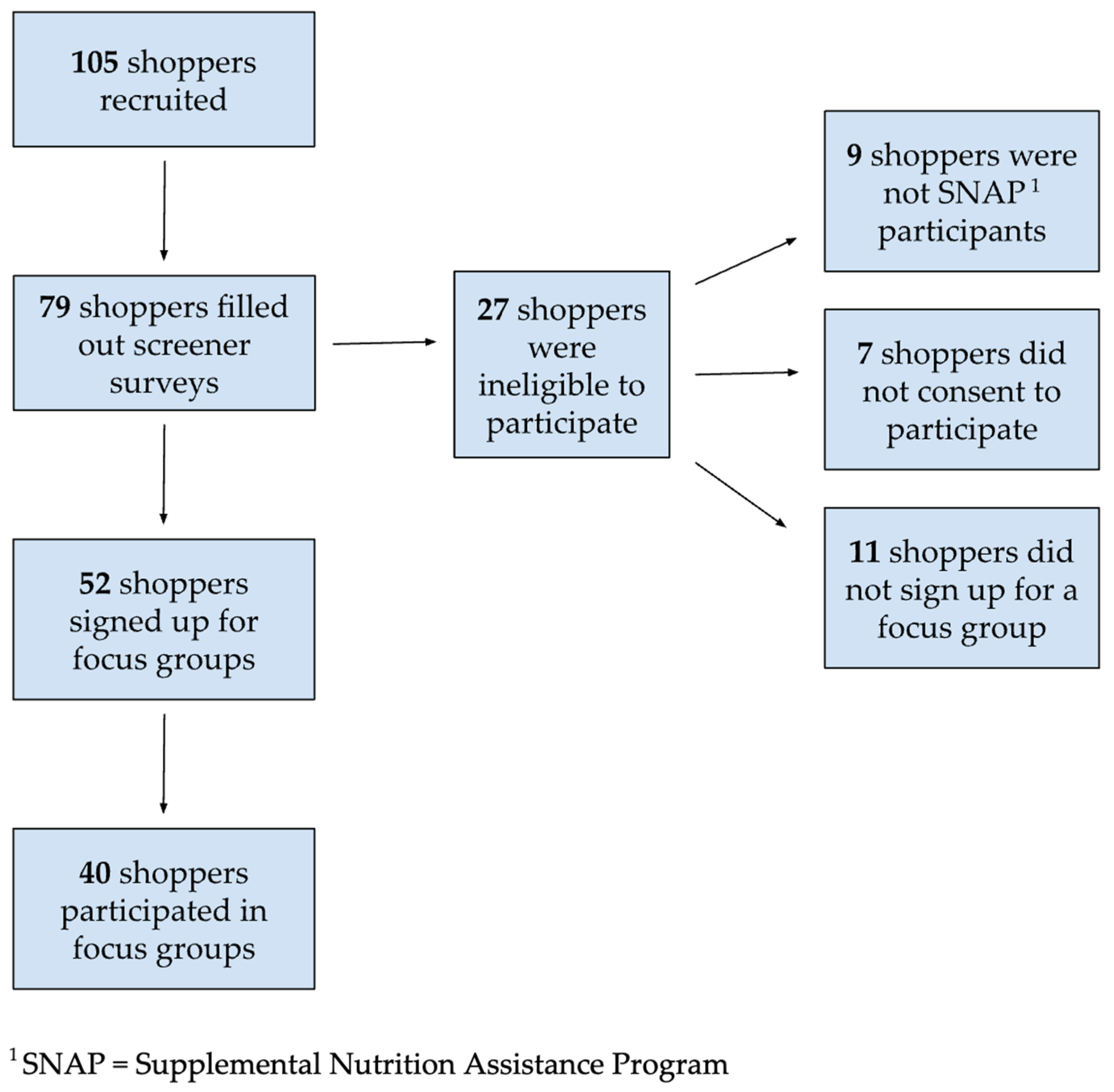

2.2.1. SNAP Shoppers

Recruitment and Screening

Data Collection

2.2.2. Farmers’ Market Staff

Recruitment and Screening

Data Collection

2.2.3. Ethical Approval

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. SNAP Shopper Focus Groups

3.2. Farmers’ Market Staff Focus Groups

3.3. Key Findings

3.3.1. Key Findings from Shopper Focus Groups

3.3.2. Key Findings from Shopper and Staff Focus Groups

3.3.3. Key Findings from Staff Focus Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Larger Benefits for Shoppers

4.2. Ability for Shoppers to Obtain the Entire Monthly Benefit at Once

4.3. Delivery of Benefits as an Electronic Rebate

4.4. Ability for Shoppers to Redeem Benefits on All SNAP-Eligible Items Anywhere That Accepts SNAP

4.5. Recommendations

4.6. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.7. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, S.H.; Moore, L.V.; Park, S.; Harris, D.M.; Blanck, H.M. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.F.; Liu, J.; Rehm, C.D.; Wilde, P.; Mande, J.R.; Mozaffarian, D. Trends and Disparities in Diet Quality Among US Adults by Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Status. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Hoffnagle, E.E.; Lindsay, A.C.; Lofink, H.E.; Hoffman, V.A.; Turrell, S.; Willett, W.C.; Blumenthal, S.J. A Qualitative Study of Diverse Experts’ Views About Barriers and Strategies to Improve the Diets and Health of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Beneficiaries. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmon, N.; Drewnowski, A. Contribution of Food Prices and Diet Cost to Socioeconomic Disparities in Diet Quality and Health: A Systematic Review and Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. SNAP Data Tables. Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-snap (accessed on 19 January 2024).

- USDA. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Food and Nutrition Service. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Fernald, L.C.H.; Gosliner, W. Alternatives to SNAP: Global Approaches to Addressing Childhood Poverty and Food Insecurity. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, S.; Lyerly, R.; Wilde, P.; Cohen, E.D.; Lawson, E.; Nunn, A. The Case for a National SNAP Fruit and Vegetable Incentive Program. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberholtzer, L.; Dimitri, C.; Schumacher, G. Linking Farmers, Healthy Foods, and Underserved Consumers: Exploring the Impact of Nutrition Incentive Programs on Farmers and Farmers’ Markets. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2012, 2, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewawitharana, S.C.; Webb, K.L.; Strochlic, R.; Gosliner, W. Comparison of Fruit and Vegetable Prices between Farmers’ Markets and Supermarkets: Implications for Fruit and Vegetable Incentive Programs for Food Assistance Program Participants. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, C.A.; Mitchell, E.; Byker Shanks, C.; Budd Nugent, N.; Reynolds, M.; Sun, K.; Zhang, N.; Yaroch, A.L. Which Program Implementation Factors Lead to More Fruit and Vegetable Purchases? An Exploratory Analysis of Nutrition Incentive Programs across the United States. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 102040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosliner, W.; Hewawitharana, S.C.; Strochlic, R.; Felix, C.; Long, C. The California Nutrition Incentive Program: Participants’ Perceptions and Associations with Produce Purchases, Consumption, and Food Security. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydell, S.A.; Turner, R.M.; Lasswell, T.A.; French, S.A.; Oakes, J.M.; Elbel, B.; Harnack, L.J. Participant Satisfaction with a Food Benefit Program with Restrictions and Incentives. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoie Roskos, M.R.; Wengreen, H.; Gast, J.; LeBlanc, H.; Durward, C. Understanding the Experiences of Low-Income Individuals Receiving Farmers’ Market Incentives in the United States: A Qualitative Study. Health Promot. Pract. 2017, 18, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budd Nugent, N.; Byker Shanks, C.; Seligman, H.K.; Fricke, H.; Parks, C.A.; Stotz, S.; Yaroch, A.L. Accelerating Evaluation of Financial Incentives for Fruits and Vegetables: A Case for Shared Measures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoloye, A.T.; Savoie-Roskos, M.R.; Durward, C.M. Higher Fruit and Vegetable Intake Is Associated with Participation in the Double Up Food Bucks (DUFB) Program. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, K.; Ruder, E.H. Fruit and Vegetable Incentive Programs for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants: A Scoping Review of Program Structure. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GusNIP NTAE. Gus Schumacher Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP): Impact Findings Y4: September 1, 2022 to August 31, 2023. 2024. Available online: https://www.nutritionincentivehub.org/media/ev5aet4n/year-4-gusnip-impact-findings-report-2024.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Karpyn, A.; Pon, J.; Grajeda, S.B.; Wang, R.; Merritt, K.E.; Tracy, T.; May, H.; Sawyer-Morris, G.; Halverson, M.M.; Hunt, A. Understanding Impacts of SNAP Fruit and Vegetable Incentive Program at Farmers’ Markets: Findings from a 13 State RCT. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vericker, T.; Dixit-Joshi, S.; Taylor, J.; May, L.; Baier, K.; Williams, E.S. Impact of Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives on Household Fruit and Vegetable Expenditures. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, G.H.; Wethington, H.; Olsho, L.; Jernigan, J.; Farris, R.; Walker, D.K. Implementing a Farmers’ Market Incentive Program: Perspectives on the New York City Health Bucks Program. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2013, 10, E145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, A.A.; Misiaszek, C.; Headrick, G.; Brosius, S.; Crone, A.; Surkan, P.J. Manager Perspectives on Implementation of a Farmers’ Market Incentive Program in Maryland. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDFA. CDFA Office of Farm to Fork—California Nutrition Incentive Program. Available online: https://cafarmtofork.cdfa.ca.gov/cnip.html (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Calise, T.; Ruggiero, L.; Spitzer, N.; Schaffer, S.; Wingerter, C. Evaluation of the Healthy Incentives Program; JSI Research & Training Institute, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Borkan, J.M. Immersion-Crystallization: A Valuable Analytic Tool for Healthcare Research. Fam. Pract. 2022, 39, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.Ti. 2023. Available online: https://atlasti.com/ (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Sam-Chen, S.; Hewawitharana, S.C.; Felix, C.; Strochlic, R.; Gosliner, W. Shopper and Farmer/Vendor Perceptions of Changed Maximum Incentive Levels at Farmers’ Markets Participating in the California Nutrition Incentive Program (GusNIP in California): Evaluation Findings; University of California Nutrition Policy Institute: Oakland, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UCSD School of Medicine, Center for Community Health. Más Fresco! Progress Report. 2020. Available online: https://masfresco.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/2020-Mas-Fresco-Progress-Report-_compressed.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Olsho, L.E.; Klerman, J.A.; Wilde, P.E.; Bartlett, S. Financial Incentives Increase Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participants: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N. Assemblymember Alex Lee Seeks $30 Million to Revive CalFresh Fruit and Vegetable Pilot Project. Available online: https://a24.asmdc.org/press-releases/20240326-assemblymember-alex-lee-seeks-30-million-revive-calfresh-fruit-and (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Gosliner, W.; Shah, H. Participant Voices: Examining Issue, Program and Policy Priorities of SNAP-Ed Eligible Adults in California. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. When did you start using Market Match at the farmers’ market? |

| 2. Have you noticed a change in the last six months in how the Market Match program works at the farmers’ market where you shop? Can you talk about how the program used to work and how that is different from how it works now? |

| 3. What do you like about the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program? What do you not like? |

| 4. How easy or difficult was it for you to understand how the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program works? |

| 5. How often do you all shop at a farmers’ market that offers the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program? Has the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program changed how often you shop at farmers’ markets? |

| 6. Where do you usually spend the incentive or extra dollars that you receive through the pilot program? |

| 7. Can you tell me about the types of items you purchase with the extra incentive dollars? Has the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program affected the way you use the extra dollars that can be spent on any CalFresh 1-eligible items? |

| 8. Can you talk about whether the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program has affected how much of your CalFresh benefits you spend at the farmers’ market? |

| 9. What changes have there been in the amount of fruits and vegetables that you and your family eat as a result of the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program? |

| 10. What changes have there been in the types of fruits and vegetables you and your family eat as a result of the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program? |

| 11. What changes have there been in the amount of other types of food you and your family have each month/week as a result of the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program? |

| 12. How about the overall amount of money you and your family have to spend each month on food? |

| 13. What recommendations do you have for improving the way the Fruit and Vegetable Pilot program works? |

| 14. For those of you that have used both the old Market Match and the new Fruit and Vegetable Pilot programs, which way do you like better? Why? |

| 1. Can you describe your understanding of the new approach to the Market Match program—or the “pilot program”? For example, how would you describe the program to a new shopper at the market? Could you describe how it differs from the way the program used to work before the pilot program started? |

| 2. What do you like about the pilot program approach to Market Match? What do you dislike about it? |

| 3. How easy or difficult has it been for you to understand the pilot program approach to Market Match? |

| 4. How easy or difficult has it been to explain the pilot program to shoppers? |

| 5. How different has it been to understand and explain the new approach compared to the old approach? |

| 6. Please describe any benefits you feel the pilot program provides to you or to your vendors or shoppers. |

| 7. Please describe any challenges you feel the pilot program introduces to you or to your vendors or shoppers. |

| 8. What feedback, if any, have you heard from CalFresh 1 shoppers and market vendors about the pilot program? |

| 9. Do you notice any changes in how CalFresh shoppers use the pilot program compared to the way they used the old approach to Market Match? |

| 10. Thinking about the old approach to Market Match and the pilot program, which do you prefer? Why? |

| 11. What recommendations do you have for improving the pilot program? |

| Group Number | Date | Market(s) Represented | Number of Participants | Focus Group Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 June 2023 | Northern California Market 1 | 2 | English |

| 2 | 23 June 2023 | Northern California Market 1 | 1 | English |

| 3 | 23 June 2023 | Northern California Market 2 | 7 | English |

| 4 | 29 June 2023 | Southern California Market 1 | 10 | English |

| 5 | 20 July 2023 | Northern California Market 3 | 9 | English |

| 6 | 10 August 2023 | Southern California Market 1 | 2 | English |

| Southern California Market 2 | 1 | |||

| Southern California Market 3 | 2 | |||

| Northern California Market 3 | 2 | |||

| 7 | 10 August 2023 | Northern California Market 2 | 4 | Spanish |

| Age | n (%) |

|---|---|

| 18–30 | 10 (25.0) |

| 31–50 | 18 (45.0) |

| 51–70 | 10 (25.0) |

| 71+ | 2 (5.0) |

| Gender (multiple responses) | n (%) |

| Woman | 26 (65.0) |

| Man | 11 (27.5) |

| Other/non-binary | 4 (10.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.5) |

| Race/Ethnicity (multiple responses) | n (%) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (2.5) |

| Asian | 10 (25.0) |

| Black or African American | 2 (5.0) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 10 (25.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1 (2.5) |

| White | 17 (42.5) |

| Other | 3 (7.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.5) |

| Highest level of education | n (%) |

| Some high school or less | 3 (7.5) |

| High school graduate, G.E.D, vocational training certificate or license | 5 (12.5) |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 12 (30.0) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 18 (45.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.5) |

| Do not know | 1 (2.5) |

| Household Income | n (%) |

| Less than USD 30,000 | 29 (72.5) |

| USD 30,000–USD 39,999 | 3 (7.5) |

| USD 40,000–USD 49,999 | 1 (2.5) |

| USD 50,000 or more | 1 (2.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (5.0) |

| Do not know | 4 (10.0) |

| Monthly Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit amount (n = 33) | Mean (Range) |

| Monthly SNAP amount (USD) | USD 343 (USD 23–USD 1200) |

| Market | Number of Participating Staff |

|---|---|

| Southern California Market 1 | 5 |

| Southern California Market 2 | 3 |

| Southern California Market 3 | 1 |

| Northern California Markets 1 and 2 1 | 3 |

| Northern California Market 3 | 2 |

| Total | 14 |

| Key Findings from Shopper Focus Groups |

|---|

| Shopper Key Finding 1: Shoppers appreciated being able to receive the entire monthly benefit during one shopping trip. |

| I like this program because they give us the money in one lump sum and that allows me to buy the most I can in just one purchase.—Spanish-speaking shopper, Southern California market I’m disabled…I try to get [to the farmers’ market] but if I can’t, then on the plus side, at least I know that I can still use [all] my Market Match. And so that’s the positive, as opposed to the way that it was designed before where I would lose out.—English-speaking shopper, Northern California market |

| Shopper Key Finding 2: Shoppers liked being able to keep the USD 60 benefit on their EBT 1 card. |

| I think when you have 60 extra dollars that’s not coming off your card, it’s always going to be helpful. And compared to, I guess, the previous Market Match, right? You have to take out $10 to get $10, right? So free money to go towards extra groceries is always helpful.—English-speaking shopper, Northern California market I think the whole grocery store thing is great. Because you can go in and get whatever you want, whenever you want.—English-speaking shopper, Northern California market |

| Shopper Key Finding 3: Most shoppers reported spending the extra USD 60 on staple items at grocery stores; however, some shoppers reported spending it at the farmers’ market. |

| What I do with that extra money, either I use it at another farmers’ market, or honestly, I buy stuff that I can’t purchase at the farmers’ market, like milk.—English-speaking shopper, Southern California market So I use mine in the grocery stores for my normal groceries. It just gives me more buying power on my [EBT] card when I go to the grocery store.—English-speaking shopper, Northern California market I buy everything I can [at the farmers’ market]; fruits, vegetables, eggs. It all gets spent.—Spanish-speaking shopper, Southern California market |

| Key Findings from Shopper Focus Groups and Staff Focus Groups |

| Shopper and Staff Key Finding 1: Shoppers and staff appreciated the ability of shoppers to obtain more benefits with the pilot. |

| That’s a no brainer, duh. $60 [per month] versus $10 [per week]? Really?—English-speaking shopper, Northern California market The shoppers who especially need the support are getting more financial incentives and the ability to purchase these healthier fruits and vegetables... And yeah, that’s super, super positive.—Staff member, Northern California market |

| Shopper and Staff Key Finding 2: Shoppers and staff felt that the pilot attracted new SNAP 2 shoppers to pilot-participating farmers’ markets. |

| I stumbled upon this program and I saw that it’s only at limited farmers’ markets, so I started going to this farmers’ market once a month to participate in this program.—English-speaking shopper, Southern California market The pilot program has brought new people, new shoppers. There’s people that just head over there because of a pilot program. And it does seem busier.—Staff member, Southern California market I think I have seen an increase in participation. So it does seem that [the pilot program] is reaching out to more of the community and people are coming out.—Staff member, Southern California market |

| Shopper and Staff Key Finding 3: Shoppers and staff reported that the pilot was difficult to understand. |

| I experienced a learning curve for sure… I think it kind of seems like for everyone it took a couple tries to fully understand what was happening.—English-speaking shopper, Southern California market What I don’t like is that [the program] is so confusing, and it’s still confusing for me.—Staff member, Southern California market |

| Shopper and Staff Key Finding 4: Shoppers and staff reported that the pilot created long lines at participating farmers’ markets. |

| I’ve seen like 10 people in line sometimes and it goes really, really slow, because [the staff are] spending so much time talking and explaining the details. —English-speaking shopper, Northern California market [Shoppers] don’t like being in the line, they don’t like how long it’s taking… Sometimes it can get a little bit tense, when you can literally see somebody’s body language change from minute 5 to minute 25 of being in a line. It just feels particularly inhumane to have people on an 80-degree day standing with no sun cover.—Staff member, Northern California market We did lose regulars who would normally come every week to spend $15 to get the $15 due to the line that we are getting now. And yeah, a lot of our seniors are getting frustrated about the wait time.—Staff member, Southern California market |

| Shopper and Staff Key Finding 5: Shoppers and staff reported technological and logistical issues when operating and using the pilot. |

| I’ve had a couple of times, some farmers markets where they’ll double charge me. And I used to try to call the CalFresh 3 customer line. And they would never reverse it. They would just say, ‘no, it’s correct.’—English-speaking shopper, Southern California market Nothing could prepare me for the scenarios and technology problems that have popped up, where you have upset customers over what’s being reflected on their receipt, and they’re thinking that they’re being dinged somehow or that we’re taking money out of their cards, things like that…. We…didn’t anticipate that there would be so many quirks with the technology and what reads on people’s EBT balances and receipts and things like that.—Staff member, Southern California market Keeping up with the amount of transactions we’re doing now is near impossible. Like we’re bringing close to $10,000 worth of coins and we’re running out halfway through the market….. We’re having to go trade, chase them down from vendors who have yet to turn them in to us for their credits.—Staff member, Northern California market |

| Key Findings from Staff Focus Groups |

| Staff Key Finding 1: Staff appreciated that shoppers had expanded shopping options; however, some expressed concerns that shoppers were spending fewer EBT dollars at the market. |

| The customers really seem to like the program, and especially the part about being able to put it on their card, still getting fresh fruits and veggies, and then being able to shop at the store with their CalFresh benefits as well.—Staff member, Northern California market I like the fact that people do have more funds that they can use anywhere that they need it. What I don’t like is that it means in a way that the farmers’ markets are subsidizing [grocery stores] and all the other places where people go to get food, and it should be the other way around.—Staff member, Southern California market |

| Staff Key Finding 2: Staff appreciated that shoppers had increased benefits, with some noting they were able to offer the full benefit to shoppers with a SNAP balance below USD 60. |

| If I had a customer that has a minimum of $23 a month… I’ll keep doing the transaction where I give them $5 of fruit and veggie vouchers, redeem it, put it back on their card and keep doing that so they have a returning balance until they hit the $60.—Staff member, Northern California market I love the fact that we’re able to stretch out benefits for some of our customers, especially those that are coming in towards the end of the month, and just have the lowest balance… The fact that we found this out has been extremely helpful. I mean, we had three [shoppers] this past weekend, I believe, that we did that for, and they were so grateful. So I love that we’re able to help them out in that in that way.—Staff member, Southern California market |

| Staff Key Finding 3: Staff expressed concerns that the pilot required more—and more highly trained—staff compared to traditional CNIP 4. |

| It costs us in personnel almost three times as much to administer this program as the original Market Match… We’ve got five people just on the EBT portion.—Staff member, Southern California market I think if they expand [the pilot] to all of our sites, we’d have staff who definitely would not be up for the challenge. They would probably not be willing to be managing it on their own at a site. Because it does take someone who’s pretty skilled, who has a lot of patience.—Staff member, Northern California market |

| Staff Key Finding 4: Staff reported that the pilot increased their workload and diminished their opportunities to engage with shoppers. |

| The [pilot] program isn’t giving us enough time to make that one-on-one connection with shoppers.—Staff member, Southern California market Keeping up with the amount of transactions we’re doing now is near impossible... It just becomes such a different experience than what [staff] signed up for and what we recruited them to do. It’s an endless cycle of never being able to breathe.—Staff member, Northern California market The backend paperwork is definitely easier with [the traditional] Market Match and takes much less time.—Staff member, Northern California market |

| Staff Key Finding 5: Staff reported concerns regarding transparency with the EBT transaction and invasive questions regarding fruit and vegetable purchases. |

| In the beginning, when we were trying to understand the program, we would just ask, ‘What are you buying today? Are you here just for fruits and veggies?’ And I would notice [shoppers] were a little apprehensive, like, ‘Why are you asking me that?’… They don’t want to share that information.—Staff member, Southern California market The process of just figuring out how you’re going to get [a shopper] to buy in and feel like they can trust the system, you know, taking $60 off of their card, and just hoping it comes back on is a really big thing to ask for a lot of people.—Staff member, Northern California market |

| Staff Key Finding 6: Staff reported heightened challenges among shoppers with limited English. |

| I think one of my biggest challenges personally at the market I run is that I have a lot of language barriers…. I have a lot of shoppers who speak Russian, Arabic, Farsi, Dari. And so the language barrier there has been a little bit challenging.—Staff member, Northern California market We have different languages that we have to communicate with people through. So that’s also been a struggle.—Staff member, Southern California market |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chelius, C.; Strochlic, R.; Hewawitharana, S.C.; Gosliner, W. Opportunities and Challenges of California’s Fruit and Vegetable Electronic Benefit Transfer Pilot Project at Farmers’ Markets: A Qualitative Study with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Shoppers and Farmers’ Market Staff. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3388. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193388

Chelius C, Strochlic R, Hewawitharana SC, Gosliner W. Opportunities and Challenges of California’s Fruit and Vegetable Electronic Benefit Transfer Pilot Project at Farmers’ Markets: A Qualitative Study with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Shoppers and Farmers’ Market Staff. Nutrients. 2024; 16(19):3388. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193388

Chicago/Turabian StyleChelius, Carolyn, Ron Strochlic, Sridharshi C. Hewawitharana, and Wendi Gosliner. 2024. "Opportunities and Challenges of California’s Fruit and Vegetable Electronic Benefit Transfer Pilot Project at Farmers’ Markets: A Qualitative Study with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Shoppers and Farmers’ Market Staff" Nutrients 16, no. 19: 3388. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193388

APA StyleChelius, C., Strochlic, R., Hewawitharana, S. C., & Gosliner, W. (2024). Opportunities and Challenges of California’s Fruit and Vegetable Electronic Benefit Transfer Pilot Project at Farmers’ Markets: A Qualitative Study with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Shoppers and Farmers’ Market Staff. Nutrients, 16(19), 3388. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16193388