Perceptions of Food Marketing and Media Use among Canadian Teenagers: A Cross-Sectional Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Survey Measures

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Most Often Used Media Platforms

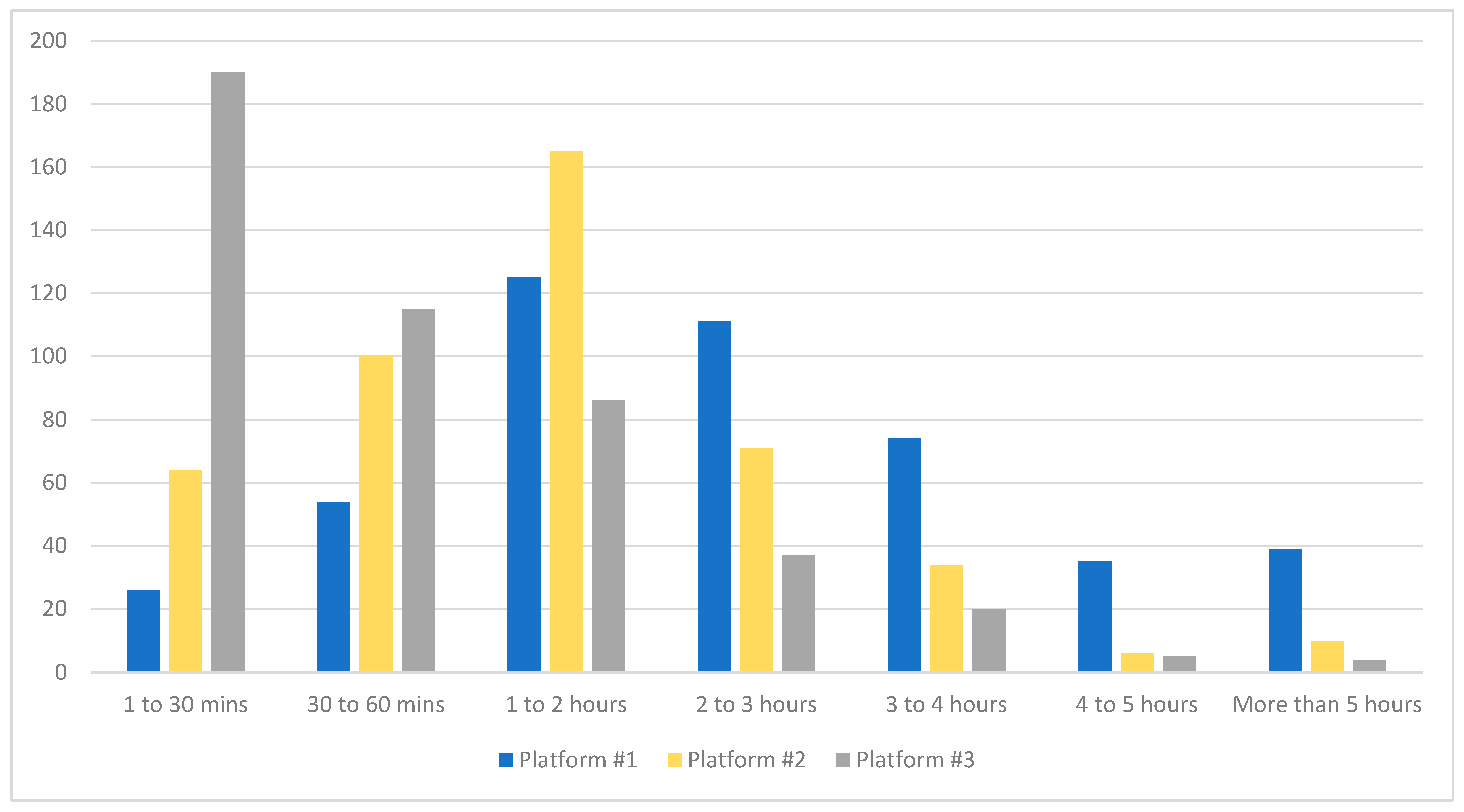

3.2. Time Spent on Media Platforms

3.3. Food and Beverage Brands Targeting Teens

3.4. Reasons for Identifying Top Food or Beverage Brands as Teen-Targeted

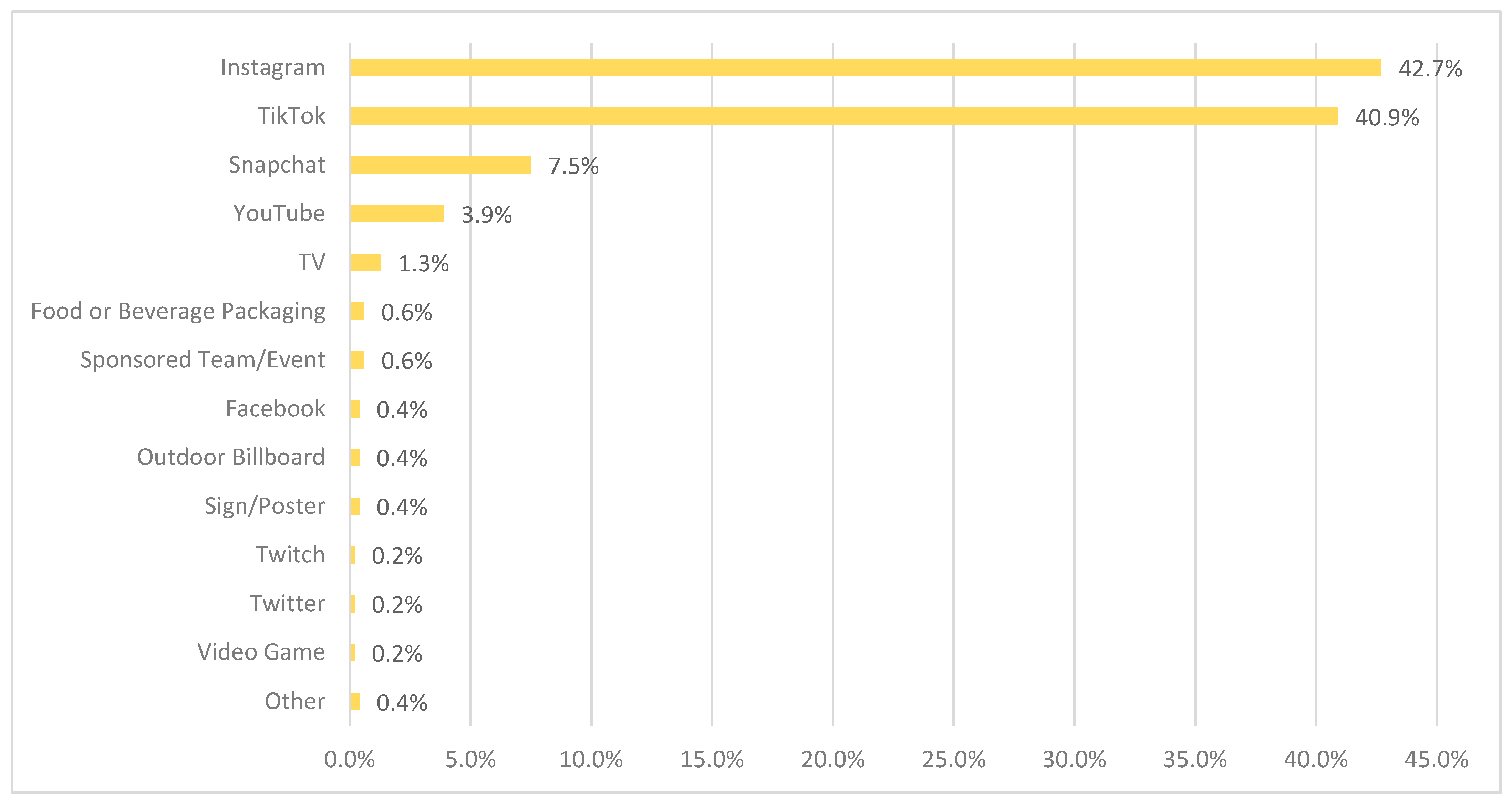

3.5. Media Platforms of Importance for Teen-Targeted Food Marketing

3.6. Teen Appealing Marketing Techniques

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kelly, B.; King, L.; Chapman, K.; Boyland, E.; Bauman, A.E.; Baur, L.A. A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: Identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e86–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyland, E. Is it ethical to advertise unhealthy foods to children? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 82, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.L.; Taillie, L.S. More than a Nuisance: Implications of Food Marketing for Public Health Efforts to Curb Childhood Obesity. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2023, 45, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, G.; Alcaire, F.; Antúnez, L.; Natero, V.; de León, C.; Gugliucci, V.; Machín, L.; Otterbring, T. Exposure effects to unfamiliar food advertisements on YouTube: A randomized controlled trial among adolescents. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 111, 104983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.K.; Christiansen, P.; Finlay, A.; Jones, A.; Maden, M.; Boyland, E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of digital game-based or influencer food and non-alcoholic beverage marketing on children and adolescents: Exploring hierarchy of effects outcomes. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksi, S.J.; Keller, K.L.; Dardis, F.; Vecchi, M.; Freeman, J.; Evans, R.K.; Boyland, E.; Masterson, T.D. The food and beverage cues in digital marketing model: Special considerations of social media, gaming, and livestreaming environments for food marketing and eating behavior research. Front. Nutr. 2024, 10, 1325265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO [World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe]. Tackling Food Marketing to Children in a Digital World: Trans-Disciplinary Perspectives. Children’s Rights, Evidence of Impact, Methodological Challenges, Regulatory Options and Policy Implications for the WHO European Region. 2016. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344003 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- WHO [World Health Organization]. Evaluating Implementation of the WHO set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children: Progress, Challenges and Guidance for Next Steps in the WHO European Region. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345153 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Qutteina, Y.; Hallez, L.; Mennes, N.; De Backer, C.; Smits, T. What Do Adolescents See on Social Media? A Diary Study of Food Marketing Images on Social Media. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Truman, E.; Black, J.E. Tracking teen food marketing: Participatory research to examine persuasive power and platforms of exposure. Appetite 2023, 186, 106550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.D.; Truman, E. Food marketing on digital platforms: What do teens see? Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.B.; Bagnato, M.; Remedios, L.; Potvin Kent, M.; Vanderlee, L.; White, C.M.; Hammond, D. Examining differences in children and adolescents’ exposure to food and beverage marketing in Canada by sociodemographic characteristics: Findings from the International Food Policy Study Youth Survey, 2020. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, M.; Roy-Gagnon, M.-H.; Vanderlee, L.; White, C.; Hammond, D.; Potvin Kent, M. The impact of fast food marketing on brand preferences and fast food intake of youth aged 10–17 across six countries. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Truman, E.; Aponte-Hao, S. Food marketing to teenagers: Examining the power and platforms of food and beverage marketing in Canada. Appetite 2022, 173, 105999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO [World Health Organization]. Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children; WHO Press, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44416/1/9789241500210_eng.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- WHO [World Health Organization]. A Framework for Implementing the Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children. 2012. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/80148/1/9789241503242_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Boyland, E.; Tatlow-Golden, M. Exposure, Power and Impact of Food Marketing on Children: Evidence Supports Strong Restrictions. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2017, 8, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Antúnez, L.; Alcaire, F.; Natero, V.; Otterbring, T. Is this advertisement designed to appeal to you? Adolescents’ views about Instagram advertisements promoting ultra-processed products. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin Kent, M.; Pauzé, E.; Roy, E.; Billy, N.; Czoli, C. Children and adolescents’ exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amson, A.; Pauzé, E.; Remedios, L.; Pritchard, M.; Potvin Kent, M. Adolescent exposure to food and beverage marketing on social media by gender: A pilot study. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ares, G.; Alcaire, F.; Gugliucci, V.; Machín, L.; de León, C.; Natero, V.; Otterbring, T. Colorful candy, teen vibes and cool memes: Prevalence and content of Instagram posts featuring ultra-processed products targeted at adolescents. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; Christiansen, P.; Masterson, T.; Barlow, G.; Boyland, E. Food and non-alcoholic beverage marketing via Fortnite streamers on Twitch: A content analysis. Appetite 2024, 195, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Morales, I.; Nieto, C.; García, A.; Espinosa-Montero, J.; Aburto, T.C.; Tatlow-Golden, M.; Boyland, E.; Barquera, S. The nature and extent of food marketing on Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube posts in Mexico. Pediatr. Obes. 2023, 18, e13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, A.; Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Maden, M.; Cerny, C.; Muc, M.; Evans, R.; Makin, H.; Boyland, E. A scoping review of outdoor food marketing: Exposure, power and impacts on eating behaviour and health. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C.; Truman, E.; LeBel, J. Food marketing to young adults: Platforms and persuasive power in Canada. Young Consum. 2024, 25, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoyne, C.; Scully, M.; Morley, B. Is food and drink advertising across various settings associated with dietary behaviours and intake among Australian adolescents? Findings from a national cross-sectional survey. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2024; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, M.; Yanamadala, S.; Roberto, C.A.; Harris, J.L.; Brownell, K.D. Athlete Endorsements in Food Marketing. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, H.; Scully, M.; Niven, P.; Kelly, B.; Chapman, K.; Donovan, R.; Martin, J.; Baur, L.A.; Crawford, D.; Wakefield, M. Effects of nutrient content claims, sports celebrity endorsements and premium offers on pre-adolescent children’s food preferences: Experimental research. Pediatr. Obes. 2014, 9, e47–e57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin Kent, M.; Pauzé, E. The Frequency and Healthfulness of Food and Beverages Advertised on Adolescents’ Preferred Web Sites in Canada. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amson, A.; Pauzé, E.; Ramsay, T.; Welch, V.; Hamid, J.S.; Lee, J.; Olstad, D.L.; Mah, C.; Raine, K.; Potvin Kent, M. Examining gender differences in adolescent exposure to food and beverage marketing through go-along interviews. Appetite 2024, 193, 107153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castronuovo, L.; Guarnieri, L.; Tiscornia, M.V.; Allemandi, L. Food marketing and gender among children and adolescents: A scoping review. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C. Promotional culture tastes teenagers: Navigating the interplay between food marketing monitoring “teen food”. In Routledge Companion to Advertising and Promotional Culture; McAllister, M., West, E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 135–146. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Gender | Number | Proportion% | Proportion% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 years | Girl | 4 | 0.9% | 1.3% |

| Boy | 2 | 0.4% | ||

| Gender Non-Conforming | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| 14 years | Girl | 26 | 5.6% | 7.8% |

| Boy | 8 | 1.7% | ||

| Gender Non-Conforming | 2 | 0.4% | ||

| 15 years | Girl | 70 | 15.1% | 19.8% |

| Boy | 18 | 3.9% | ||

| Gender Non-Conforming | 4 | 0.9% | ||

| 16 years | Girl | 119 | 25.6% | 34.3% |

| Boy | 25 | 5.4% | ||

| Gender Non-Conforming | 15 | 3.2% | ||

| 17 years | Girl | 127 | 27.4% | 36.9% |

| Boy | 28 | 6.0% | ||

| Gender Non-Conforming | 16 | 3.4% |

| #1 Most Used Platform | #2 Most Used Platform | #3 Most Used Platform | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Platform | Number | Proportion% | Platform | Number | Proportion% | Platform | Number | Proportion% |

| 1 | 207 | 44.6% | 135 | 29.1% | YouTube | 106 | 22.8% | ||

| 2 | TikTok | 140 | 30.2% | TikTok | 116 | 25% | 101 | 21.8% | |

| 3 | Snapchat | 57 | 12.3% | YouTube | 81 | 17.5% | Snapchat | 93 | 20% |

| 4 | YouTube | 38 | 8.2% | Snapchat | 76 | 16.4% | TikTok | 45 | 9.7% |

| 5 | TV | 4 | 0.9% | 11 | 2.4% | Website | 21 | 4.5% | |

| 6 | Website | 4 | 0.9% | Video Game | 10 | 2.2% | TV | 19 | 4.1% |

| 7 | Video Game | 3 | 0.6% | TV | 9 | 1.9% | 18 | 3.9% | |

| 8 | Food or Beverage Packaging | 2 | 0.4% | Website | 9 | 1.9% | 11 | 2.4% | |

| 9 | Sign/Poster | 2 | 0.4% | 5 | 1.1% | Food or Beverage Packaging | 11 | 2.4% | |

| 10 | 1 | 0.2% | Food or Beverage Packaging | 4 | 0.9% | Sign/Poster | 11 | 2.4% | |

| 11 | Twitch | 1 | 0.2% | Sign/Poster | 2 | 0.4% | Video Game | 11 | 2.4% |

| 12 | 1 | 0.2% | Twitch | 1 | 0.2% | Outdoor Billboard | 6 | 1.3% | |

| 13 | Magazine | 0 | 0 | Magazine | 0 | 0 | Twitch | 3 | 0.6% |

| 14 | Outdoor Billboard | 0 | 0 | Outdoor Billboard | 0 | 0 | Sponsored Event | 1 | 0.2% |

| 15 | Sponsored Event | 0 | 0 | Sponsored Event | 0 | 0 | Magazine | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Other | 3 | 0.6% | Other | 4 | 0.9% | Other | 9 | 1.9% |

| #1 Food or Beverage Brand (n = 459) | #2 Food or Beverage Brand (n = 415) | #3 Food or Beverage Brand (n = 366) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Brand | Number | Proportion% | Brand | Number | Proportion% | Brand | Number | Proportion% |

| 1 | McDonald’s | 131 | 28.5% | McDonald’s | 65 | 15.7% | McDonald’s | 38 | 10.4% |

| 2 | Starbucks | 73 | 15.9% | Starbucks | 53 | 12.8% | Starbucks | 29 | 7.9% |

| 3 | Coca-Cola | 40 | 8.7% | Coca-Cola | 29 | 7.0% | Coca-Cola | 29 | 7.9% |

| 4 | Tim Hortons | 19 | 4.1% | Tim Hortons | 23 | 5.5% | Tim Hortons | 22 | 6.0% |

| 5 | Prime | 13 | 2.8% | Prime | 15 | 3.6% | Subway | 20 | 5.5% |

| 6 | Monster Energy | 9 | 2.0% | Subway | 13 | 3.1% | Burger King | 12 | 3.3% |

| 7 | Doritos | 9 | 2.0% | Monster Energy | 10 | 2.4% | Taco Bell | 8 | 2.2% |

| 8 | Oreo | 7 | 1.5% | Hershey | 9 | 2.2% | Wendy’s | 7 | 1.9% |

| 9 | Sprite | 7 | 1.5% | Wendy’s | 9 | 2.2% | Monster Energy | 6 | 1.6% |

| 10 | Sour Patch Kids | 6 | 1.3% | Chatime | 8 | 1.9% | Dairy Queen | 6 | 1.6% |

| Reason (n = 277, More than One Reason Could Be Provided) | Number | Proportion% |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Techniques/Content (top 3: special offer, 22%; visual style, 18%, celebrity, 15%, n = 162) | 138 | 49.5% |

| Low Price | 52 | 18.6% |

| Appeal of Food Itself (i.e., taste) | 33 | 11.8% |

| Accessibility/Convenience | 31 | 11.1% |

| Ad Platform/Location | 19 | 6.8% |

| Social/Emotional Value | 1 | 0.4% |

| Other | 3 | 1.1% |

| Reason (n = 180, More than One Reason Could Be Provided) | Number | Proportion% |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Techniques/Content (top 3: visual style, 37%; theme, 24%, interactivity, 10%, n = 117) | 111 | 61.7% |

| Ad Platform | 21 | 11.7% |

| Social/Emotional Value | 20 | 11.1% |

| Appeal of Food Itself (i.e., taste) | 19 | 10.6% |

| Accessibility/Convenience | 3 | 1.7% |

| Other | 3 | 1.7% |

| Reasons (n = 109, More than One Reason Could Be Provided) | Number | Proportion% |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Techniques/Content (top 3: visual style, 29%; special offer, 18%; celebrity, 14%, n = 74) | 66 | 60.6% |

| Appeal of Food Itself (i.e., taste) | 21 | 19.3% |

| Ad Platform/Location | 20 | 18.3% |

| Accessibility/Convenience | 1 | 0.9% |

| Reasons (n = 71, More than One Reason Could Be Provided) | Number | Proportion% |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing Techniques/Content (top 3: celebrity, 41%, special offer, 25%, visual style, 13%, n = 32) | 31 | 43.7% |

| Low Price | 17 | 23.9% |

| Accessibility/Convenience | 10 | 14.1% |

| Appeal of Food Itself (i.e., taste) | 5 | 7.0% |

| Ad Platform/Location | 4 | 5.6% |

| Social/Emotional Value | 4 | 5.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truman, E.; Elliott, C. Perceptions of Food Marketing and Media Use among Canadian Teenagers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172987

Truman E, Elliott C. Perceptions of Food Marketing and Media Use among Canadian Teenagers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients. 2024; 16(17):2987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172987

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruman, Emily, and Charlene Elliott. 2024. "Perceptions of Food Marketing and Media Use among Canadian Teenagers: A Cross-Sectional Survey" Nutrients 16, no. 17: 2987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172987

APA StyleTruman, E., & Elliott, C. (2024). Perceptions of Food Marketing and Media Use among Canadian Teenagers: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Nutrients, 16(17), 2987. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172987