Single-Person Households: Insights from a Household Survey of Fruit and Vegetable Purchases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Probit Analysis

2.2. Data

3. Results

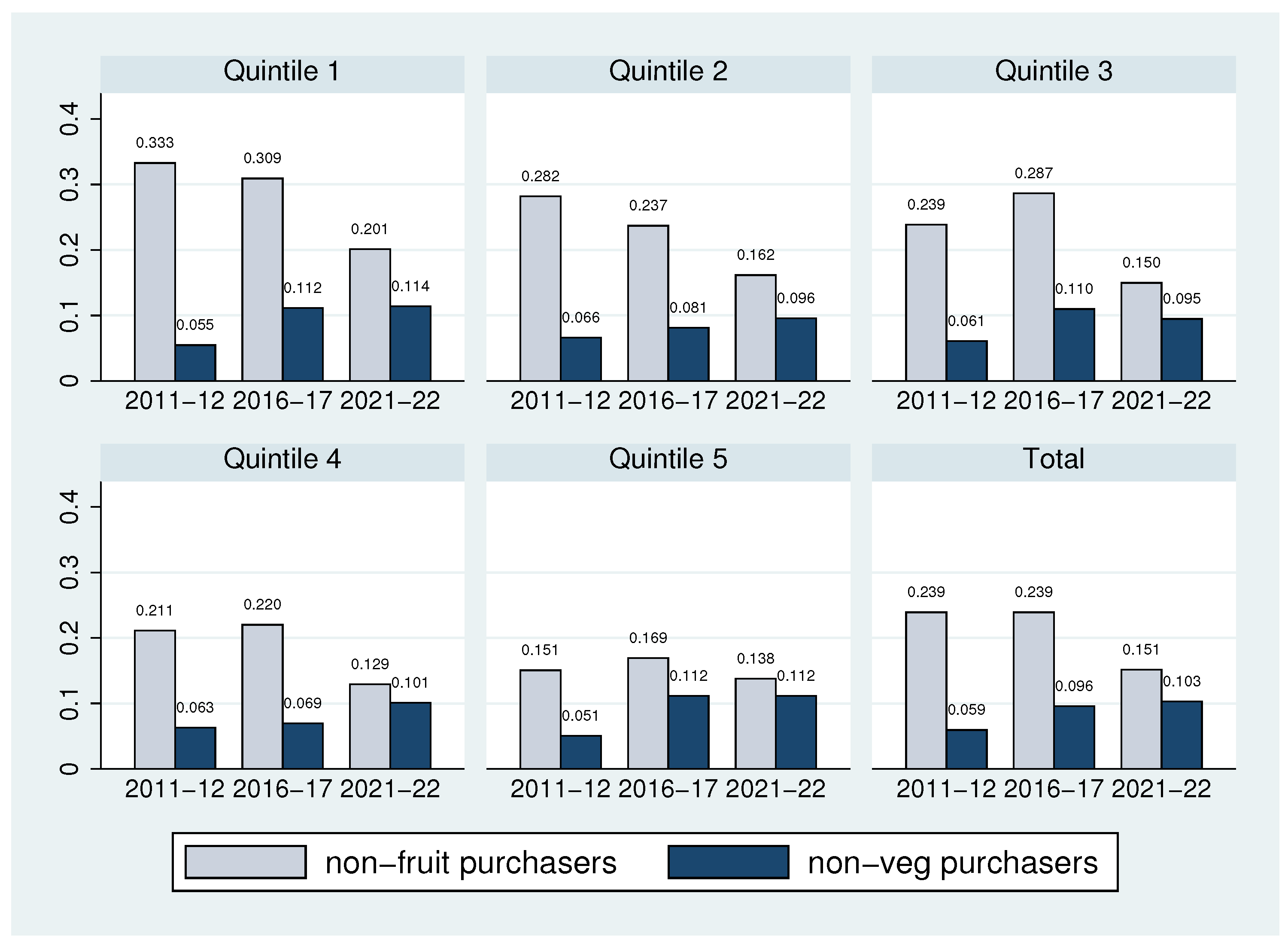

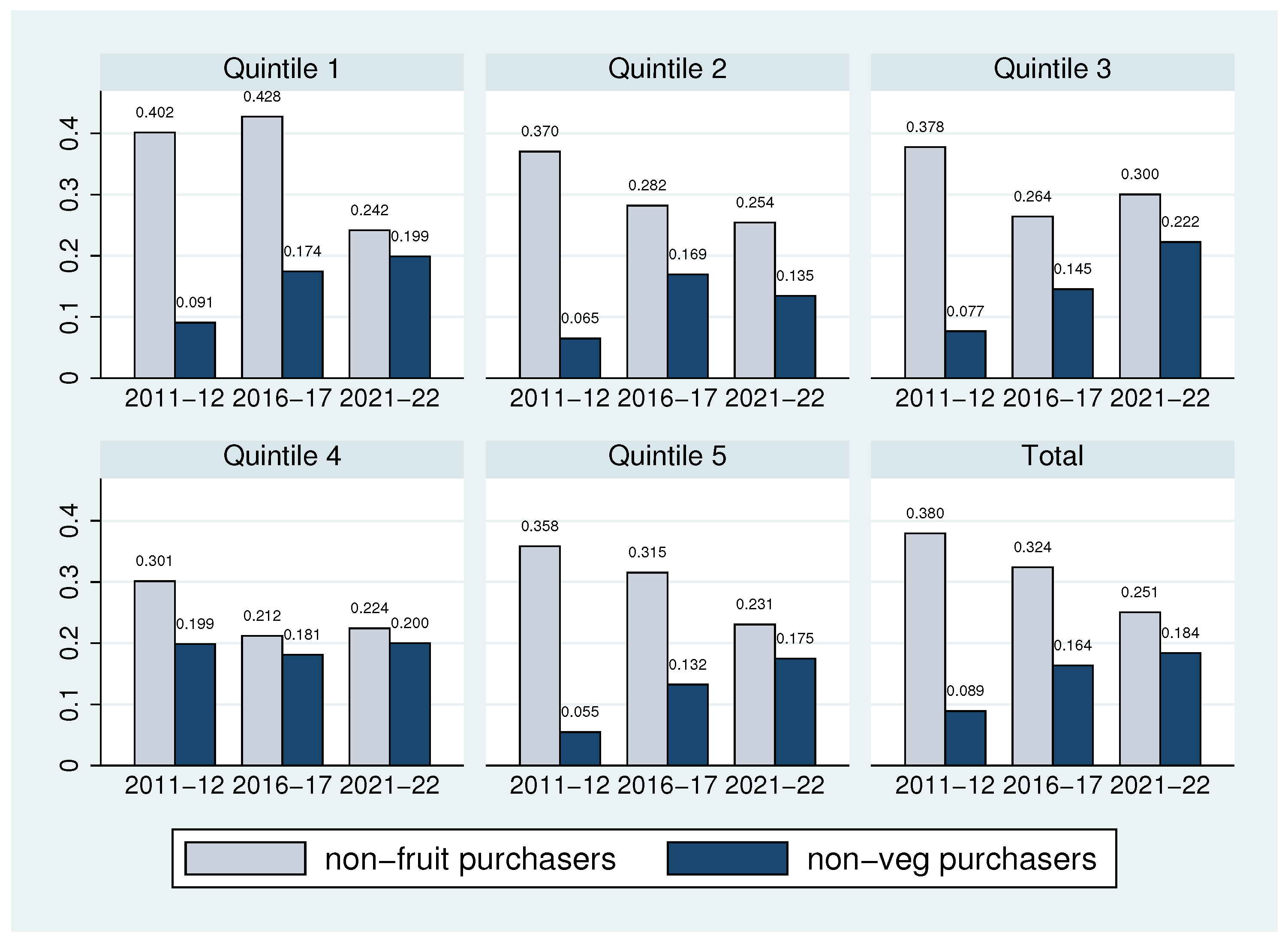

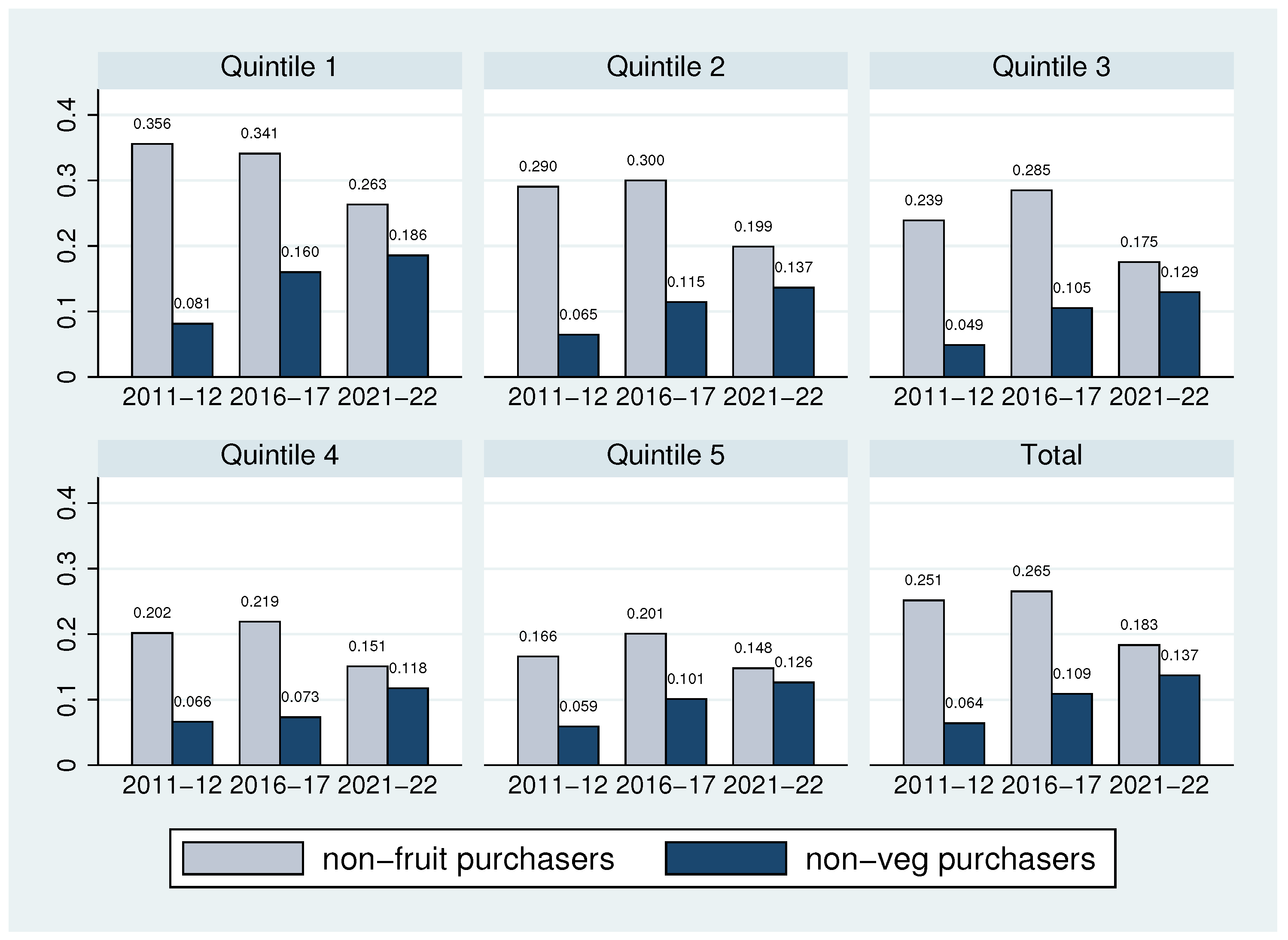

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Probit Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Non-Fruit Purchasers | Fruit Purchasers | Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Fruit portions | 0.000 | (0.000) | 2.295 | (2.260) | −2.218 *** |

| Vegetable portions | 0.636 | (1.286) | 2.488 | (2.382) | −1.806 *** |

| Head of Household Characteristics | |||||

| Gender of head, 1 = male, 2 = female | 1.428 | (0.495) | 1.429 | (0.495) | 0.017 |

| Age of head of household, years | 48.173 | (16.041) | 50.628 | (15.348) | −1.699 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.045 | (0.208) | 0.034 | (0.180) | 0.015 *** |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.085 | (0.279) | 0.076 | (0.265) | 0.018 ** |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.146 | (0.353) | 0.154 | (0.361) | 0.005 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.444 | (0.497) | 0.456 | (0.498) | −0.017 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.280 | (0.449) | 0.281 | (0.449) | −0.020 * |

| Food Shopper Characteristics | |||||

| Gender of food shopper, male | 0.292 | (0.455) | 0.157 | (0.364) | 0.105 *** |

| Gender of food shopper, female | 0.424 | (0.494) | 0.445 | (0.497) | −0.006 |

| Gender of food shopper, combination | 0.284 | (0.451) | 0.398 | (0.489) | −0.099 *** |

| Age of food shopper, years | 47.339 | (15.510) | 49.668 | (14.353) | −1.484 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.040 | (0.195) | 0.023 | (0.150) | 0.018 *** |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.086 | (0.280) | 0.077 | (0.267) | 0.019 ** |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.164 | (0.370) | 0.199 | (0.399) | −0.012 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.466 | (0.499) | 0.462 | (0.499) | −0.015 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.245 | (0.430) | 0.239 | (0.427) | −0.010 |

| Household Composition | |||||

| Number of men | 1.221 | (1.001) | 1.573 | (1.031) | −0.304 *** |

| Number of women | 1.308 | (0.934) | 1.488 | (0.997) | −0.166 *** |

| Number of children | 0.583 | (0.906) | 0.700 | (0.959) | −0.106 *** |

| Household Structure | |||||

| Single-person | 0.295 | (0.456) | 0.133 | (0.340) | 0.137 *** |

| Adults/seniors without children | 0.345 | (0.475) | 0.434 | (0.496) | −0.068 *** |

| An adult/senior with children | 0.075 | (0.263) | 0.050 | (0.218) | 0.023 *** |

| Adults/seniors with children | 0.285 | (0.451) | 0.382 | (0.486) | −0.092 *** |

| Household Characteristics | |||||

| High income | 0.182 | (0.386) | 0.235 | (0.424) | −0.054 *** |

| Observations | 2926 | 12,085 | 15,011 | ||

| Non-Veg Purchasers | Vegetable Purchasers | Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Vegetable portions | 0.000 | (0.000) | 2.490 | (2.338) | −2.476 *** |

| Fruit portions | 0.450 | (1.256) | 2.101 | (2.263) | −1.575 *** |

| Head of Household Characteristics | |||||

| Gender of head, 1 = man, 2 = female | 1.413 | (0.492) | 1.431 | (0.495) | −0.003 |

| Age of head of household, years | 47.609 | (15.868) | 50.586 | (15.409) | −2.350 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.032 | (0.175) | 0.036 | (0.187) | −0.001 |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.058 | (0.234) | 0.081 | (0.272) | −0.018 ** |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.132 | (0.339) | 0.156 | (0.363) | −0.012 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.429 | (0.495) | 0.457 | (0.498) | −0.020 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.348 | (0.477) | 0.270 | (0.444) | 0.051 *** |

| Food Shopper Characteristics | |||||

| Gender food shopper, man | 0.344 | (0.475) | 0.156 | (0.363) | 0.149 *** |

| Gender food shopper, woman | 0.408 | (0.492) | 0.446 | (0.497) | −0.029 * |

| Gender food shopper, combination | 0.247 | (0.432) | 0.398 | (0.489) | −0.120 *** |

| Age of food shopper, years | 47.072 | (15.444) | 49.585 | (14.431) | −1.831 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.030 | (0.171) | 0.025 | (0.158) | 0.007 |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.063 | (0.243) | 0.081 | (0.273) | −0.012 |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.143 | (0.350) | 0.200 | (0.400) | −0.036 *** |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.447 | (0.497) | 0.465 | (0.499) | −0.019 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.317 | (0.465) | 0.228 | (0.420) | 0.060 *** |

| Household Composition | |||||

| Number of men | 1.125 | (0.983) | 1.569 | (1.030) | −0.371 *** |

| Number of women | 1.243 | (0.904) | 1.489 | (0.997) | −0.207 *** |

| Number of children | 0.528 | (0.860) | 0.703 | (0.962) | −0.134 *** |

| Household Structure | |||||

| Single-person | 0.348 | (0.476) | 0.134 | (0.340) | 0.179 *** |

| Adults/seniors without children | 0.314 | (0.464) | 0.434 | (0.496) | −0.098 *** |

| An adult/senior with children | 0.073 | (0.261) | 0.052 | (0.222) | 0.022 *** |

| Adults/seniors with children | 0.265 | (0.441) | 0.380 | (0.485) | −0.102 *** |

| Household Characteristics | |||||

| High income | 0.208 | (0.406) | 0.228 | (0.420) | −0.022 * |

| Observations | 2194 | 12,817 | 15,011 | ||

References

- OECD. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondonno, N.P.; Davey, R.J.; Murray, K.; Radavelli-Bagatini, S.; Bondonno, C.P.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Sim, M.; Magliano, D.J.; Daly, R.M.; Shaw, J.E.; et al. Associations between fruit intake and risk of diabetes in the AusDiab cohort. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4097–e4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharzadeh, E.; Siassi, F.; Qorbani, M.; Koohdani, F.; Pak, N.; Sotoudeh, G. Fruits and vegetables intake and its subgroups are related to depression: A cross-sectional study from a developing country. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalmpourtzidou, A.; Eilander, A.; Talsma, E.F. Global vegetable intake and supply compared to recommendations: A systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervilla, N.; Salamanca, A.S.; Calandri, E.; Albrecht, C. Análisis del consumo, utilización y aprovechamiento de frutas y verduras entre los años 2019 y 2021. Diaeta (B. Aires) 2022, 40, e22040001. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio_de_Salud. Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2016–2017 Primeros Resultados. Gobierno de Chile. 2017; pp. 1–61. Available online: https://www.chilelibredetabaco.cl/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/ENS_2016_17_primeros_resultados.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- IHME. Diet Low in Fruit, Vegetable and Legumes; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation: Seattle, WA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ansai, N.; Wambogo, E.A. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption among Adults in the United States, 2015–2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021, 397, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.; Magana-Lemus, D.; Godoy, D. The effect of education on fruit and vegetable purchase disparities in Chile. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2756–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louro, T.; Simões, C.; Castelo, P.M.; Capela E Silva, F.; Luis, H.; Moreira, P.; Lamy, E. How Individual Variations in the Perception of Basic Tastes and Astringency Relate with Dietary Intake and Preferences for Fruits and Vegetables. Foods 2021, 10, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turati, F.; Rossi, M.; Pelucchi, C.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C. Fruit and vegetables and cancer risk: A review of southern European studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, S102–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Lim, M.; Kim, J. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 122, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C. Logit and Probit Models; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. 7ma Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares 2011–2012. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/estadisticas/sociales/ingresos-y-gastos/encuesta-de-presupuestos-familiares (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- INE. Metodología IX Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares. Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. 2024. Available online: https://www.ine.gob.cl/docs/default-source/encuesta-de-presupuestos-familiares/metodologia/ix-epf-(octubre-2021---septiembre-2022)/metodologia-ix-epf.pdf?sfvrsn=e2db6cfe_8 (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Esteve, A.; Pohl, M.; Becca, F.; Fang, H.; Galeano, J.; García-Román, J.; Reher, D.; Trias-Prats, R.; Turu, A. A global perspective on household size and composition, 1970–2020. Genus 2024, 80, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Lee, Y. Selection attributes of home meal replacement by food-related lifestyles of single-person households in South Korea. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 66, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H.; Kim, J.M. Relationship between eating behavior and healthy eating competency of single-person and multi-person households by age group. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2021, 26, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, S.H.; Lee, J.W.; Bae, D.Y.; Kim, Y.K. Development of a dietary education program for Korean young adults in single-person households. J. Korean Home Econ. Educ. Assoc. 2021, 33, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chang, B.P.; Hristov, H.; Pravst, I.; Profeta, A.; Millard, J. Changes in food consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of consumer survey data from the first lockdown period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, N.; Guo, Z.; Nakata, R. A human voice, but not human visual image makes people perceive food to taste better and to eat more:“Social” facilitation of eating in a digital media. Appetite 2021, 167, 105644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Park, E.C.; Ju, Y.J.; Nam, J.Y.; Kim, T.H. Is one’s usual dinner companion associated with greater odds of depression? Using data from the 2014 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2016, 62, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, Y.; Kondo, N.; Takagi, D.; Saito, M.; Hikichi, H.; Ojima, T.; Kondo, K. Combined effects of eating alone and living alone on unhealthy dietary behaviors, obesity and underweight in older Japanese adults: Results of the JAGES. Appetite 2015, 95, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T.; Russell, J.; Campbell, M.J.; Barker, M.E. Do ‘food deserts’ influence fruit and vegetable consumption?—A cross-sectional study. Appetite 2005, 45, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadlmayr, B.; Trübswasser, U.; McMullin, S.; Karanja, A.; Wurzinger, M.; Hundscheid, L.; Riefler, P.; Lemke, S.; Brouwer, I.D.; Sommer, I. Factors affecting fruit and vegetable consumption and purchase behavior of adults in sub-Saharan Africa: A rapid review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1113013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terin, M.; Birinci, A.; Bilgic, A.; Urak, F. Determinants of fresh and frozen fruit and vegetable expenditures in turkish households: A bivariate tobit model approach. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundari, K.; Arifalo, S.F. Determinants of household demand for fresh fruit and vegetable in Nigeria: A double hurdle approach. Q. J. Int. Agric. 2013, 52, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Verain, M.C.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Taufik, D.; Raaijmakers, I.; Reinders, M.J. Motive-based consumer segments and their fruit and vegetable consumption in several contexts. Food Res. Int. 2020, 127, 108731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Goméz-Corona, C.; Valentin, D. Femininities & masculinities: Sex, gender, and stereotypes in food studies. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 33, 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Caraher, M.; Dixon, P.; Lang, T.; Carr-Hill, R. The state of cooking in England: The relationship of cooking skills to food choice. Br. Food J. 1999, 101, 590–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Allen, J. Gender differences in healthy and unhealthy food consumption and its relationship with depression in young adulthood. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraher, M.; Lang, T. Can’t cook, won’t cook: A review of cooking skills and their relevance to health promotion. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 1999, 37, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrogué, C.; Orlicki, M.E. Factores relacionados al consumo de frutas y verduras en base a la Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo en Argentina: Factors related to the consumption of fruits and vegetables based on the National Survey of Risk Factors in Argentina. Rev. Pilquen 2019, 22, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Were, V.; Foley, L.; Musuva, R.; Pearce, M.; Wadende, P.; Lwanga, C.; Mogo, E.; Turner-Moss, E.; Obonyo, C. Socioeconomic inequalities in food purchasing practices and expenditure patterns: Results from a cross-sectional household survey in western Kenya. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 943523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora Vergara, A.P.; López Espinoza, A.; Martínez Moreno, A.G.; Bernal Gómez, S.J.; Martínez Rodríguez, T.Y.; Hun Gamboa, N. Determinantes socioeconómicos y sociodemográficos asociados al consumo de frutas y verduras de las madres de familia y los hogares de escolares de Jalisco. Nutr. Hosp. 2022, 39, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, V.; Yusuf, S.; Chow, C.K.; Dehghan, M.; Corsi, D.J.; Lock, K.; Popkin, B.; Rangarajan, S.; Khatib, R.; Lear, S.A.; et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e695–e703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, G.L.; Rodrigues, V.M.; Bastos, B.S.; Uggioni, P.L.; Hauschild, D.B.; Fernandes, A.C.; Martinelli, S.S.; Cavalli, S.B.; Bray, J.; Hartwell, H.; et al. Association of personal characteristics and cooking skills with vegetable consumption frequency among university students. Appetite 2021, 166, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passanha, A.; Benício, M.H.D.; Venâncio, S.I. Determinants of fruits, vegetables, and ultra-processed foods consumption among infants. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva 2021, 26, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, L.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. The contribution of three components of nutrition knowledge to socio-economic differences in food purchasing choices. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1814–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachucki, M.C.; Karter, A.J.; Adler, N.E.; Moffet, H.H.; Warton, E.M.; Schillinger, D.; O’Connell, B.H.; Laraia, B. Eating with others and meal location are differentially associated with nutrient intake by sex: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Appetite 2018, 127, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Non-Fruit Purchasers | Fruit Purchasers | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||

| Fruit portions | 0.000 | 2.295 | −2.218 *** |

| Vegetable portions | 0.636 | 2.488 | −1.806 *** |

| Head of Household Characteristics | |||

| Gender of head, 1 = male, 2 = female | 1.428 | 1.429 | 0.017 |

| Age of head of household, years | 48.173 | 50.628 | −1.699 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.045 | 0.034 | 0.015 *** |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.085 | 0.076 | 0.018 ** |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.146 | 0.154 | 0.005 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.444 | 0.456 | −0.017 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.280 | 0.281 | −0.020 * |

| Food Shopper Characteristics | |||

| Gender of food shopper, male | 0.292 | 0.157 | 0.105 *** |

| Gender of food shopper, female | 0.424 | 0.445 | −0.006 |

| Gender of food shopper, combination | 0.284 | 0.398 | −0.099 *** |

| Age of food shopper, years | 47.339 | 49.668 | −1.484 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.040 | 0.023 | 0.018 *** |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.019 ** |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.164 | 0.199 | −0.012 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.466 | 0.462 | −0.015 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.245 | 0.239 | −0.010 |

| Household Composition | |||

| Number of men | 1.221 | 1.573 | −0.304 *** |

| Number of women | 1.308 | 1.488 | −0.166 *** |

| Number of children | 0.583 | 0.700 | −0.106 *** |

| Household Structure | |||

| Single-person | 0.295 | 0.133 | 0.137 *** |

| Adults/seniors without children | 0.345 | 0.434 | −0.068 *** |

| An adult/senior with children | 0.075 | 0.050 | 0.023 *** |

| Adults/seniors with children | 0.285 | 0.382 | −0.092 *** |

| Household Characteristics | |||

| High income | 0.182 | 0.235 | −0.054 *** |

| Observations | 2926 | 12,085 | 15,011 |

| Non-Veg Purchasers | Vegetable Purchasers | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | ||

| Vegetable portions | 0.000 | 2.490 | −2.476 *** |

| Fruit portions | 0.450 | 2.101 | −1.575 *** |

| Head of Household Characteristics | |||

| Gender of head, 1 = male, 2 = female | 1.413 | 1.431 | −0.003 |

| Age of head of household, years | 47.609 | 50.586 | −2.350 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.032 | 0.036 | −0.001 |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.058 | 0.081 | −0.018 ** |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.132 | 0.156 | −0.012 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.429 | 0.457 | −0.020 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.348 | 0.270 | 0.051 *** |

| Food Shopper Characteristics | |||

| Gender of food shopper, male | 0.344 | 0.156 | 0.149 *** |

| Gender of food shopper, female | 0.408 | 0.446 | −0.029 * |

| Gender of food shopper, combination | 0.247 | 0.398 | −0.120 *** |

| Age of food shopper, years | 47.072 | 49.585 | −1.831 *** |

| Education, less than 4 years | 0.030 | 0.025 | 0.007 |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.063 | 0.081 | −0.012 |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.143 | 0.200 | −0.036 *** |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.447 | 0.465 | −0.019 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.317 | 0.228 | 0.060 *** |

| Household Composition | |||

| Number of men | 1.125 | 1.569 | −0.371 *** |

| Number of women | 1.243 | 1.489 | −0.207 *** |

| Number of children | 0.528 | 0.703 | −0.134 *** |

| Household Structure | |||

| Single-person | 0.348 | 0.134 | 0.179 *** |

| Adults/seniors without children | 0.314 | 0.434 | −0.098 *** |

| An adult/senior with children | 0.073 | 0.052 | 0.022 *** |

| Adults/seniors with children | 0.265 | 0.380 | −0.102 *** |

| Household Characteristics | |||

| High income | 0.208 | 0.228 | −0.022 * |

| Observations | 2194 | 12,817 | 15,011 |

| Variable | EPFVII (2011–2012) | EPFVIII (2016–2017) | EPFIX (2021–2022) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SD | Effect | SD | Effect | SD | |

| Head of Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Gender of head, 1 = male, 2 = female | −0.027 ** | 0.010 | −0.025 ** | 0.009 | −0.023 ** | 0.009 |

| Age of head of household, years | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 *** | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Education, 4–8 years | −0.043 | 0.029 | 0.030 | 0.026 | −0.005 | 0.026 |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.040 | 0.027 | 0.008 | 0.027 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.010 | 0.028 | 0.042 | 0.029 | 0.035 | 0.028 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.036 | 0.033 | 0.041 | 0.033 | 0.041 | 0.031 |

| Food Shopper Characteristics | ||||||

| Gender of food shopper, female | 0.046 *** | 0.013 | 0.054 *** | 0.012 | 0.068 *** | 0.013 |

| Gender of food shopper, combination | 0.043 ** | 0.016 | 0.071 *** | 0.012 | 0.071 *** | 0.012 |

| Age of food shopper | 0.004 *** | 0.001 | 0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.002 ** | 0.001 |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.077 * | 0.035 | −0.008 | 0.030 | 0.041 | 0.030 |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.092 ** | 0.034 | 0.037 | 0.031 | 0.077 * | 0.032 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.138 *** | 0.035 | 0.066 * | 0.032 | 0.075 * | 0.034 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.181 *** | 0.039 | 0.135 *** | 0.035 | 0.093 * | 0.037 |

| Household Composition | ||||||

| Number of men | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.045 *** | 0.005 | 0.034 *** | 0.005 |

| Number of women | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0.020 *** | 0.005 | 0.019 *** | 0.005 |

| Number of children | 0.015 | 0.008 | −0.038 *** | 0.008 | −0.028 *** | 0.008 |

| Household Structure | ||||||

| Adults/seniors without children | 0.126 *** | 0.019 | 0.086 *** | 0.015 | 0.080 *** | 0.014 |

| An adult/senior with children | 0.073 ** | 0.028 | 0.101 *** | 0.022 | 0.076 *** | 0.019 |

| Adults/seniors with children | 0.157 *** | 0.023 | 0.125 *** | 0.018 | 0.107 *** | 0.018 |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| High income | 0.045 *** | 0.013 | 0.040 *** | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.010 |

| Observations | 10,431 | 15,183 | 15,009 | |||

| Variable | EPFVII (2011–2012) | EPFVIII (2016–2017) | EPFIX (2021–2022) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SD | Effect | SD | Effect | SD | |

| Head of Household Characteristics | ||||||

| Gender of head, 1 = male, 2 = female | 0.002 | 0.006 | −0.003 | 0.007 | −0.015 | 0.008 |

| Age of head of household, years | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 * | 0.000 |

| Education, 4–8 years | −0.024 | 0.017 | −0.018 | 0.016 | 0.010 | 0.021 |

| Education, 8–12 years | −0.017 | 0.016 | −0.013 | 0.017 | −0.023 | 0.023 |

| Education, 12–16 years | −0.007 | 0.015 | −0.038 * | 0.018 | −0.013 | 0.024 |

| Education, more than 16 years | −0.005 | 0.018 | −0.033 | 0.021 | −0.021 | 0.027 |

| Food Shopper Characteristics | ||||||

| Gender of food shopper, female | 0.024 ** | 0.008 | 0.043 *** | 0.009 | 0.083 *** | 0.013 |

| Gender of food shopper, combination | 0.031 *** | 0.009 | 0.046 *** | 0.009 | 0.090 *** | 0.012 |

| Age of food shopper | 0.001 ** | 0.000 | 0.001** | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Education, 4–8 years | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.027 | 0.023 | 0.029 |

| Education, 8–12 years | 0.010 | 0.021 | 0.047 | 0.028 | 0.053 | 0.030 |

| Education, 12–16 years | 0.014 | 0.021 | 0.065 * | 0.029 | 0.048 | 0.032 |

| Education, more than 16 years | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.071 * | 0.031 | 0.038 | 0.034 |

| Household Composition | ||||||

| Number of men | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.031 *** | 0.004 | 0.028 *** | 0.005 |

| Number of women | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.018 *** | 0.004 | 0.020 *** | 0.005 |

| Number of children | 0.016 ** | 0.005 | −0.018 ** | 0.006 | −0.024 *** | 0.007 |

| Household Structure | ||||||

| Adults/seniors without children | 0.099 *** | 0.015 | 0.085 *** | 0.012 | 0.079 *** | 0.013 |

| An adult/senior with children | 0.067 ** | 0.021 | 0.060 *** | 0.017 | 0.071 *** | 0.017 |

| Adults/seniors with children | 0.104 *** | 0.018 | 0.100 *** | 0.015 | 0.090 *** | 0.016 |

| Household Characteristics | ||||||

| High income | −0.005 | 0.007 | −0.013 | 0.007 | −0.002 | 0.008 |

| Observations | 10,431 | 15,183 | 15,009 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, A.; Rivera, M.; Durán-Agüero, S.; Sactic, M.I. Single-Person Households: Insights from a Household Survey of Fruit and Vegetable Purchases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172851

Silva A, Rivera M, Durán-Agüero S, Sactic MI. Single-Person Households: Insights from a Household Survey of Fruit and Vegetable Purchases. Nutrients. 2024; 16(17):2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172851

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Andres, Maripaz Rivera, Samuel Durán-Agüero, and Maria Isabel Sactic. 2024. "Single-Person Households: Insights from a Household Survey of Fruit and Vegetable Purchases" Nutrients 16, no. 17: 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172851

APA StyleSilva, A., Rivera, M., Durán-Agüero, S., & Sactic, M. I. (2024). Single-Person Households: Insights from a Household Survey of Fruit and Vegetable Purchases. Nutrients, 16(17), 2851. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16172851