Survey of Physicians and Healers Using Amygdalin to Treat Cancer Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Questionnaire

- (1)

- Demographic data, including age, gender, and education.

- (2)

- Use of amygdalin, experience, and assessment of its therapeutic potential.

- (3)

- Source of information on amygdalin and patient communication.

- (4)

- Therapeutic strategy, evaluation of response, and assessment of toxicity.

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data and Education

3.2. Use of Amygdalin

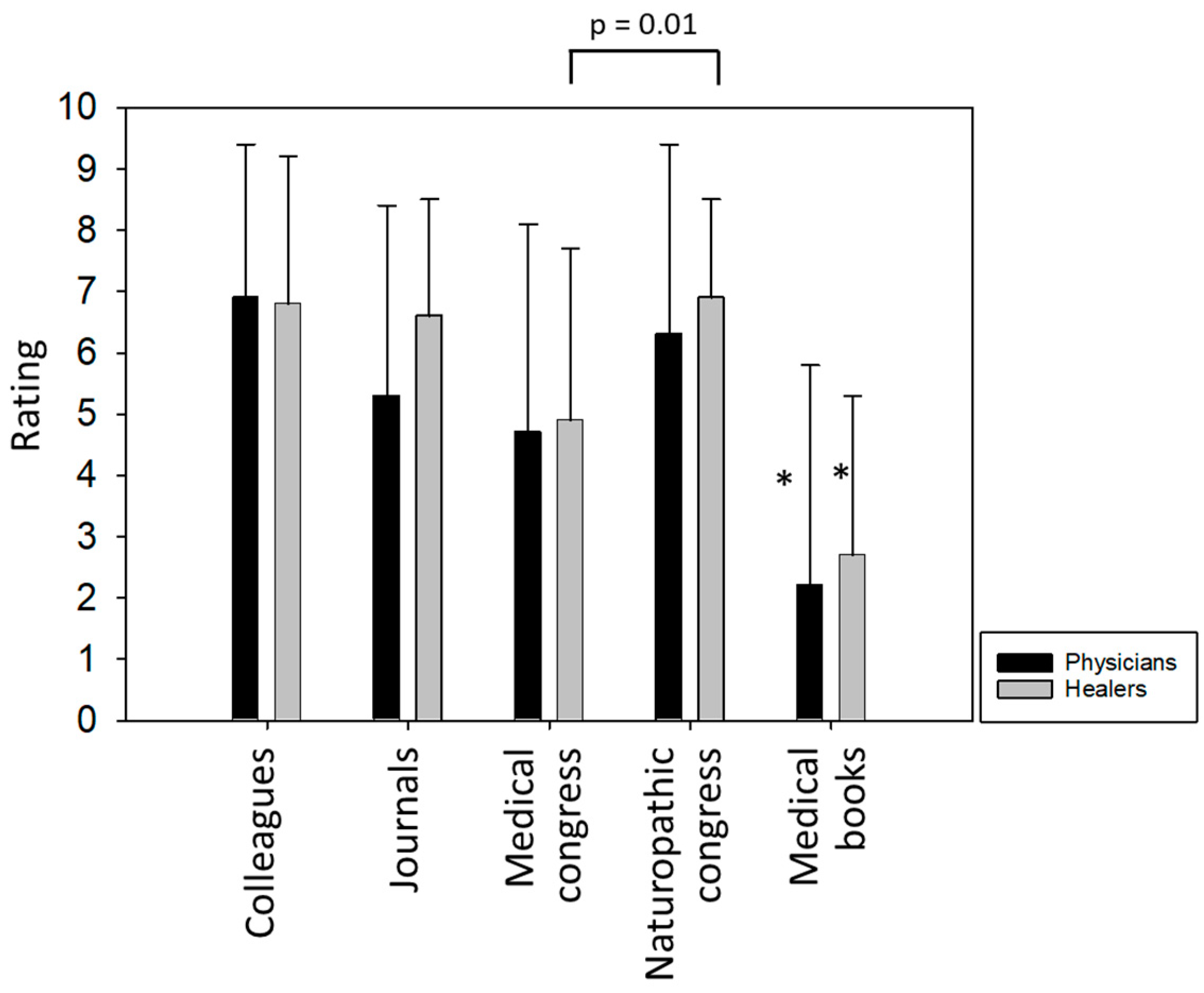

3.3. Information Sources

3.4. Patient Communication

3.5. Therapeutic Strategy

3.6. Control of Toxic Effects and Therapeutic Response to Amygdalin

3.7. Amygdalin Efficacy

3.8. Scientific Knowledge and Expectations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renet, S.; de Chevigny, A.; Hoacoglu, S.; Belkarfa, A.L.; Jardin-Szucs, M.; Bezie, Y.; Jouveshomme, S. Risk evaluation of the use of complementary and alternative medicines in cancer. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2021, 79, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejewska, A.; Ślusarska, B.J.; Szadowska-Szlachetka, Z.; Rudnicka-Drożak, E.; Panasiuk, L. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in patients with cancer and their relationship with health behaviours—Cross-sectional study. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2021, 28, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Källman, M.; Bergström, S.; Carlsson, T.; Järås, J.; Holgersson, G.; Nordberg, J.H.; Nilsson, J.; Wode, K.; Bergqvist, M. Use of CAM among cancer patients: Results of a regional survey in Sweden. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debes, A.M.; Koenig, A.; Strobach, D.; Schinkoethe, T.; Forster, M.; Harbeck, N.; Wuerstlein, R. Biologically Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Breast Cancer Patients and Possible Drug-Drug Interactions. Breast Care 2023, 18, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöcker, A.; Mehnert-Theuerkauf, A.; Hinz, A.; Ernst, J. Utilization of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) by women with breast cancer or gynecological cancer. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, J.; Welter, S.; Ciarlo, G.; Käsmann, L.; Ahmadi, E.; Keinki, C. Patient activation, self-efficacy and usage of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuser, A.K.; Hack, C.C.; Fasching, P.A.; Antoniadis, S.; Grasruck, K.; Wasner, S.; Knoll, S.; Sievers, H.; Beckmann, M.W.; Thiel, F.C. Patterns and Trends of Herbal Medicine Use among Patients with Gynecologic Cancer. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2021, 81, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, J.; Micke, O.; Muecke, R.; Buentzel, J.; Prott, F.J.; Kleeberg, U.; Senf, B.; Muenstedt, K. PRIO (Working Group Prevention and Integrative Oncology of the German Cancer Society): User rate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) of patients visiting a counseling facility for CAM of a German comprehensive cancer center. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 943–948. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, R.W. Patient perspectives: Tijuana cancer clinics in the post-NAFTA era. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaheta, R.A.; Nelson, K.; Haferkamp, A.; Juengel, E. Amygdalin, quackery or cure? Phytomedicine 2016, 23, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moertel, C.G.; Ames, M.M.; Kovach, J.S.; Moyer, T.P.; Rubin, J.R.; Tinker, J.H. A pharmacologic and toxicological study of amygdalin. JAMA 1981, 245, 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanoudaki, M.; Stoumpou, S.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Karafyllaki, D.; Solovos, E.; Papadopoulos, K.; Giannakoula, A.; Giaginis, C. Amygdalin as a Promising Anticancer Agent: Molecular Mechanisms and Future Perspectives for the Development of New Nanoformulations for Its Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczak-Wilke, E.; Polkowska, Ż.; Koprowski, M.; Owsianik, K.; Mitchell, A.E.; Bałczewski, P. Amygdalin: Toxicity, Anticancer Activity and Analytical Procedures for Its Determination in Plant Seeds. Molecules 2021, 26, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed Mohammad Salleh, S.N.; Farooqui, M.; Gnanasan, S.; Karuppannan, M. Use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) among Malaysian cancer patients for the management of chemotherapy related side effects (CRSE). J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2021, 18, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskulluoglu, M.; Uchańska, B.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Zygulska, A.L.; Zielińska, P.; Grela-Wojewoda, A. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among Polish cancer patients. Nowotwory J. Oncol. 2021, 71, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzycka, K.; Kurzawa, M.; Kucharz, M.; Godawska, M.; Oleksa, M.; Stawowy, M.; Slupinska-Borowka, K.; Sznek, W.; Gisterek, I.; Boratyn-Nowicka, A.; et al. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use in Hospitalized Cancer Patients-Study from Silesia, Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, C.; Buntzel, J.; von Weikersthal, L.F.; Junghans, C.; Zomorodbakhsch, B.; Stoll, C.; Prott, F.J.; Fuxius, S.; Micke, O.; Richter, A.; et al. Usage of Complementary and Alternative Methods, Lifestyle, and Psychological Variables in Cancer Care. In Vivo 2023, 37, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. Bitter Apricot Kernels Can Lead to Poisoning. Available online: https://www.bfr.bund.de/en/press_information/2007/07/bitter_apricot_kernels_can_lead_to_poisoning-9432.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board. Laetrile/Amygdalin (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]; National Cancer Institute (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buckner, C.A.; Lafrenie, R.M.; Dénommée, J.A.; Caswell, J.M.; Want, D.A. Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients before and after a cancer diagnosis. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, e275–e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelfire, Therapies/Protocols. Available online: https://www.angelfire.com/in/curecancer/Therapies.html (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- CytoPharma. Amygdalin Injectable solution. Available online: https://www.cytopharmaonline.com/en/amigdalina-solucion-inyectable-box-of-10-vials (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Arztpraxis Christoph Polanski. Available online: https://www.hausdoc.com/schwerpunkte/integrative-krebstherapie/amygdalin.html (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Mentink, M.D.C.; van Vliet, L.M.; Timmer-Bonte, J.A.N.H.; Noordman, J.; van Dulmen, S. How is complementary medicine discussed in oncology? Observing real-life communication between clinicians and patients with advanced cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 3235–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.W.; Fan, W.; Ko, S.G.; Song, L.; Bian, Z.X. Evidence-based management of herb-drug interaction in cancer chemotherapy. Explore 2010, 6, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutten, R.J.; Weil, C.R.; King, A.J.; Barney, B.; Bylund, C.L.; Fagerlin, A.; Gaffney, D.K.; Gill, D.; Scherer, L.; Suneja, G.; et al. Multi-Institutional Analysis of Cancer Patient Exposure, Perceptions, and Trust in Information Sources Regarding Complementary and Alternative Medicine. JCO Oncol. Pract. 2023, 19, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarlo, G.; Ahmadi, E.; Welter, S.; Hübner, J. Factors influencing the usage of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2021, 44, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, K.; Pawlik, J.; Czekawy, I.; Kozłowski, M.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. Complementary Methods in Cancer Treatment-Cure or Curse? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standish, L.J.; Malani, S.M.; Lynch, K.; Whinkin, E.J.; McCotter, C.M.; Lynch, D.A.; Aggarwal, S.K. Integrative Oncology’s 30-Year Anniversary: What Have We Achieved? A North American Naturopathic Oncology Perspective. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 15347354231178911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S.J.; Hunter, J.; Seely, D.; Balneaves, L.G.; Rossi, E.; Bao, T. Integrative Oncology: International Perspectives. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 1534735418823266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moertel, C.G.; Fleming, T.R.; Rubin, J.; Kvols, L.K.; Sarna, G.; Koch, R.; Currie, V.E.; Young, C.W.; Jones, S.E.; Davignon, J.P. A clinical trial of amygdalin (Laetrile) in the treatment of human cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1982, 306, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unproven methods of cancer management: Contreras methods. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1971, 21, 317–321. [CrossRef]

- Bora, A.; Wilma Delphine Silvia, C.R.; Mohanty, S.; Pinnelli, V.B. Amygdalin laetrile-a nascent vitamin B17: A review. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 2160–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, I.; Thurn, K.; Juengel, E.; Oppermann, E.; Nelson, K.; Thomas, C.; Bartsch, G.; Oremek, G.M.; Haferkamp, A.; Rubenwolf, P.; et al. Evaluation of TKTL1 as a biomarker in serum of prostate cancer patients. Cent. European J. Urol. 2016, 69, 247–251. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, J.; Rutz, J.; Maxeiner, S.; Juengel, E.; Bon, D.; Roos, F.; Chun, F.K.; Blaheta, R.A. Cyanide and lactate levels in patients during chronic oral amygdalin intake followed by intravenous amygdalin administration. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 43, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shi, F.; Zhang, R.; Sun, C.; Gong, C.; Jian, L.; Ding, L. Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Amygdalin and Paeoniflorin After Single and Multiple Intravenous Infusions of Huoxue-Tongluo Lyophilized Powder for Injection in Healthy Chinese Volunteers. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, P. Influence of Amygdalin Treatment on Clinical Progress and Tumor Relevant Serum Enzymes in 29 Cancer Patients. Ph.D. Thesis, Medical Faculty of the Georg August-University Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, P.; Huang, A.; Luo, Y.; Tchakerian, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C. Effects of using WeChat/WhatsApp on physical and psychosocial health outcomes among oncology patients: A systematic review. Health Inform. J. 2023, 29, 14604582231164697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebbia, V.; Piazza, D.; Valerio, M.R.; Firenze, A. WhatsApp Messenger use in oncology: A narrative review on pros and contras of a flexible and practical, non-specific communication tool. Ecancermedicalscience 2021, 15, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, M.M.; Kovach, J.S.; Flora, K.P. Initial pharmacologic studies of amygdalin (laetrile) in man. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1978, 22, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rauws, A.G.; Olling, M.; Timmerman, A. The pharmacokinetics of amygdalin. Arch. Toxicol. 1982, 49, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Qi, S.; Fang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cheng, X.; Liu, P.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and anti-liver fibrosis characteristics of amygdalin: Key role of the deglycosylated metabolite prunasin. Phytomedicine 2022, 99, 154018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.N.; Li, N.; Chen, Z.C.; Guo, Y.L.; Tian, C.J.; Cheng, D.J.; Tang, X.Y.; Zhang, X.Y. Amyg-dalin alleviated TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in bronchial epithelial cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 369, 110235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Fang, K.; Wang, G.; Guan, X.; Pang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Ran, N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F. Protective effect of amygdalin on epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in experimental chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mice. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Hou, J.; Rao, J.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, W. Magnetically Directed Enzyme/Prodrug Prostate Cancer Therapy Based on β-Glucosidase/Amygdalin. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 4639–4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wen, J.; Xu, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, T.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, K.; et al. Amygdalin Induced Mitochon-dria-Mediated Apoptosis of Lung Cancer Cells via Regulating NF[Formula: See text]B-1/NF[Formula: See text]B Signaling Cascade in Vitro and in Vivo. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022, 50, 1361–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Li, H.; Pan, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Li, J.; Li, S. Effects of Ganfule capsule on microbial and met-abolic profiles in anti-hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 2280–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sex [(n (%)] | Age (Years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Males | Females | Mean ± SD | Min | Max |

| All | 26 (68) | 12 (32) | 58.3 ± 8.1 | 37 | 81 |

| Physicians | 17 (85) | 3 (15) | 59.0 ± 7.5 | 40 | 71 |

| Healers | 9 (50) | 9 (50) | 57.4 ± 8.7 | 37 | 81 |

| Education [(n (%)] a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Acupuncture b | Naturopathy b | Nutritional Medicine | Homeopathy b | Physical Therapy | Manual Medicine | Psychotherapy | MTT c | Palliative Medicine |

| All | 8 (21) | 15 (40) | 9 (24) | 9 (24) | 4 (11) | 8 (21) | 3 (8) | 8 (21) | 4(11) |

| Physicians | 7 (35) | 11 (55) | 5 (25) | 8 (40) | 2 (10) | 6 (30) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | 0 (0) |

| Healers | 1 (6) | 4 (22) | 4 (22) | 1 (6) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) | 3 (17) | 4 (22) | 4(22) |

| Amygdalin Use a | Patients/Quarter a | Continue Amygdalin b | Conventional Treatment b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | (Years) | (Number) | Yes | No | Always | Mostly | Not | NR |

| All | 8.8 ± 5.5 | 18.6 ± 48.2 | 36 (95) | 2 (5) | 8 (21) | 25 (66) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) |

| Physicians | 8.8 ± 6.2 | 8.3 ± 13.0 | 20 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | 12 (60) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Healers | 8.8 ± 4.7 | 30.2 ± 66.9 | 16 (89) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) | 13 (72) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Category | Pharmacy a,b | Manufacturer | Internet |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 25 (66) | 16 (42) | 2 (5) |

| Physicians | 16 (80) | 6 (30) | 2 (10) |

| Healers | 9 (50) c | 10 (56) | 0 (0) |

| Category | Convinced a,b | Patient Wish | NR | First Choice | Not First Choice | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 30 (79) | 11 (29) | 3 (8) | 16 (42) | 5 (13) | 21 (55) |

| Physicians | 16 (80) | 6 (30) | 1 (5) | 5 (25) | 4 (20) | 9 (45) |

| Healers | 14 (78) | 5 (28) | 2 (11) | 11 (61) c | 1 (6) | 12 (67) |

| ||||||

| Category | Lab Test a,b Positive | Patient Dependent | Additional Compounds | Financial Situation | Therapeutic Break | |

| All | 7 (18) | 5 (13) | 7 (18) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | |

| Physicians | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | |

| Healers | 4 (22) | 3 (17) | 4 (22) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| Category | Symptom Relief a,b | Progression Delay | Cure | NR | Early Stage a,b | Advanced Stage | All Stages | Palliative | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 21 (55) | 34 (90) | 16 (42) | 1 (3) | 19 (50) | 4 (11) | 20 (53) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) |

| Physicians | 13 (65) | 18 (90) | 5 (25) | 1 (5) | 9 (45) | 1 (5) | 14 (70) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Healers | 8 (44) | 16 (89) | 11 (61) c | 0 (0) | 10 (56) | 3 (17) | 6 (33) c | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Initial | Colleagues a,b | Internet, Media | Scientific Literature | Congress (Reports) | Patients | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 21 (55) c | 10 (26) | 8 (21) | 18 (47) | 12 (32) | 1 (3) |

| Physicians | 11 (55) | 7 (35) | 3 (15) | 7 (35) | 8 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Healers | 10 (56) | 3 (17) | 5 (28) | 11 (61) | 4 (22) | 1 (6) |

| Continued | Colleagues a,b | Internet | Reference Books | Scientific Journals | Congress | Other |

| All | 32 (84) | 23 (60) | 31 (82) d | 20 (53) | 26 (68) | 2 (5) |

| Physicians | 18 (90) | 16 (80) e | 16 (80) | 12 (60) | 14 (70) | 1 (5) |

| Healers | 14 (78) | 7 (39) | 15 (83) | 8 (44) | 12 (67) | 1 (6) |

| Category | Information by User a | Patients‘ Satisfaction a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Good | Not Necessary b | Very Good | Good | |

| All | 35 (92) | 3 (8) | 29 (76) | 9 (24) |

| Physicians | 18 (90) | 2 (10) | 15 (75) | 5 (25) |

| Healers | 17 (94) | 1 (6) | 14 (78) | 4 (22) |

| Category | Application a | Optimum Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | i.v. | Oral | i.v. | |

| All | 12 (32) | 38 (100) | 3 (8) | 35 (92) |

| Physicians | 6 (30) | 20 (100) | 1 (5) | 19 (95) |

| Healers | 6 (33) | 18 (100) | 2 (11) | 16 (89) |

| Category | 1×/Week a | 1–2×/Week | 2–3×/Week | 3–5×/Week | 5×/Week | Individually | NR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 2 (5) | 10 (26) | 6 (16) | 4 (11) | 10 (26) | 5 (13) | 1 (3) |

| Physicians | 2 (10) | 5 (25) | 4 (20) | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Healers | 0 (0) | 5 (28) | 2 (11) | 1 (6) | 7 (39) b | 3 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Category | Only One Cycle a,b | Refular Intervals | Patient Dependent | Other | Dosage | ||

| Constant | Increasing | NR | |||||

| All | 3 (8) | 28 (74) | 9 (24) | 4 (11) | 6 (16) | 29 (76) | 3 (8) |

| Physicians | 2 (10) | 15 (75) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 3 (15) | 15 (75) | 2 (10) |

| Healers | 1 (6) | 13 (72) | 6 (33) | 2 (11) | 3 (17) | 14 (78) | 1 (6) |

| Start | 3 g a | 6 g | 7.5 g | 9 g | 12 g | NR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 16 (42) | 8 (21) | 1 (3) | 9 (24) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | ||

| Physicians | 10 (50) | 4 (20) | 0 (0) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) | ||

| Healers | 6 (33) | 4 (22) | 1 (6) | 6 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | ||

| End | 3 g a | 9 g | 12 g | 15 g | 18 g | 24 g | 27 g | NR |

| All | 1 (3) | 10 (26) | 5 (13) | 8 (21) | 7 (18) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 3 (8) |

| Physicians | 1 (5) | 5 (25) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 4 (20) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Healers | 0 (0) | 5 (28) | 3 (17) | 4 (22) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 1 (6) |

| Category | Limited Response a,b | Worsened Condition | Other | NR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protocol | Tolerability | ||||

| All | 17 (45) | 8 (21) | 5 (13) | 5 (13) | 5 (13) |

| Physicians | 8 (40) | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 3 (15) |

| Healers | 9 (50) | 3 (17) | 2 (11) | 3 (17) | 2 (11) |

| Category | Colleagues a,b | Internet, Media | Scientific Literature | Congress (Reports) | Patients | Own Experience | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Supplier | |||||||

| All | 27 (71) c | 6 (16) | 4 (11) | 19 (50) | 3 (8) | 18 (47) c | 2 (5) | 3 (8) |

| Physicians | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | 1 (5) | 10 (50) | 3 (15) | 8 (40) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Healers | 12 (67) | 1 (6) | 3 (17) | 9 (50) | 0 (0) | 10 (56) | 2 (11) | 2 (11) |

| Category | Cyanide Control a | Reason for No Control a,b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Not Necessary | Patient Confusion | Cumbersome | Too Expensive | No Cyanide Release | Other | NR | |

| All | 4 (11) | 34 (90) | 24 (63) | 7 (18) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) | 6 (16) | 4 (11) | 5 (13) |

| Physicians | 1 (5) | 19 (95) | 14 (70) | 3 (15) | 1 (5) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| Healers | 3 (17) | 15 (83) | 10 (56) | 4 (22) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (22) | 3 (17) | 3 (17) |

| Category | Clinical Examination a,b | Imaging | Physician’s Letter | Patient Report | Laboratory Data | Lab Data—Examples c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | TM | ETM | NETM | ||||||

| All | 25 (66) | 25 (66) | 14 (37) | 11 (29) | 31 (82) | 8 | 10 | 8 | 6 |

| Physicians | 11 (55) | 12 (60) | 5 (25) | 7 (35) | 17 (85) | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| Healers | 14 (78) | 13 (72) | 3 (17) | 4 (22) | 14 (78) | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 |

| Category | Compliance Control a | Info on Amygdalin Use a | Info on Amygdalin Response a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | NR | Always | Mostly | Rarely | No | NR | Yes | No | NR | |

| All | 25 (66) | 5 (13) | 8 (21) | 3 (8) | 7 (18) | 10 (26) | 16 (42) | 2 (5) | 8 (21) | 27 (71) | 3 (8) |

| Physicians | 14 (70) | 3 (15) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 10 (50) | 2 (10) | 4 (20) | 14 (70) | 2 (10) |

| Healers | 11 (61) | 2 (11) | 5 (28) | 1 (6) | 5 (28) | 6 (33) | 6 (33) | 0 (0) | 4 (22) | 13 (72) | 1 (6) |

| Category | Potential of Amygdalin a,b | Additional Factors a,b | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | Medium | Moderate | Unclear | NR | Indication | Dosing | Nutrition | Lifestyle | Multimodal | |

| All | 10 (26) | 17 (45) | 7 (18) | 4 (11) | 2 (5) | 25 (66) | 22 (58) | 26 (68) | 17 (45) | 17 (45) |

| Physicians | 3 (15) | 9 (45) | 5 (25) | 3 (15) | 2 (10) | 13 (65) | 13 (65) | 11 (55) | 6 (30) | 9 (45) |

| Healers | 7 (39) c | 8 (44) | 2 (11) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 12 (67) | 9 (50) | 15 (83) | 11 (61) | 8 (44) |

| Category | Clinical Studies a,b | Medical Congresses | Medical Books | Medical Guidelines | Reference Center | Open Mindedness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 34 (90) | 29 (76) | 16 (42) | 23 (61) | 24 (63) | 35 (92) |

| Physicians | 16 (80) | 18 (90) | 9 (45) | 12 (60) | 12 (60) | 17 (85) |

| Healers | 18 (100) | 11 (61) c | 7 (39) | 11 (61) | 12 (67) | 18 (100) |

| Category | Active Component a,b | Bioavailability | Tolerability | Study Results | Scientific Exchange | Presenting Ideas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 9 (24) | 11 (29) | 11 (29) | 28 (74) | 28 (74) | 13 (34) |

| Physicians | 4 (20) | 5 (25) | 7 (35) | 15 (75) | 13 (65) | 5 (25) |

| Healers | 5 (28) | 6 (33) | 4 (22) | 13 (72) | 15 (83) | 8 (44) |

| Category | Evaluating Results a | Study Participation a | Future Participation a | Provide Data a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | NR | Yes | No | NR | |

| All | 10 (26) | 28 (74) | 6 (16) | 32 (84) | 22 (58) | 12 (32) | 4 (11) | 13 (34) | 12 (32) | 13 (34) |

| Physicians | 4 (20) | 16 (80) | 3 (15) | 17 (85) | 13 (65) | 5 (25) | 2 (10) | 8 (40) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) |

| Healers | 6 (33) | 12 (67) | 3 (17) | 15 (83) | 9 (50) | 7 (39) | 2 (11) | 5 (28) | 5 (28) | 8 (44) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Markowitsch, S.D.; Binali, S.; Rutz, J.; Chun, F.K.-H.; Haferkamp, A.; Tsaur, I.; Juengel, E.; Fischer, N.D.; Thomas, A.; Blaheta, R.A. Survey of Physicians and Healers Using Amygdalin to Treat Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132068

Markowitsch SD, Binali S, Rutz J, Chun FK-H, Haferkamp A, Tsaur I, Juengel E, Fischer ND, Thomas A, Blaheta RA. Survey of Physicians and Healers Using Amygdalin to Treat Cancer Patients. Nutrients. 2024; 16(13):2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132068

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarkowitsch, Sascha D., Sali Binali, Jochen Rutz, Felix K.-H. Chun, Axel Haferkamp, Igor Tsaur, Eva Juengel, Nikita D. Fischer, Anita Thomas, and Roman A. Blaheta. 2024. "Survey of Physicians and Healers Using Amygdalin to Treat Cancer Patients" Nutrients 16, no. 13: 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132068

APA StyleMarkowitsch, S. D., Binali, S., Rutz, J., Chun, F. K.-H., Haferkamp, A., Tsaur, I., Juengel, E., Fischer, N. D., Thomas, A., & Blaheta, R. A. (2024). Survey of Physicians and Healers Using Amygdalin to Treat Cancer Patients. Nutrients, 16(13), 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16132068