Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet: An Update of a Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

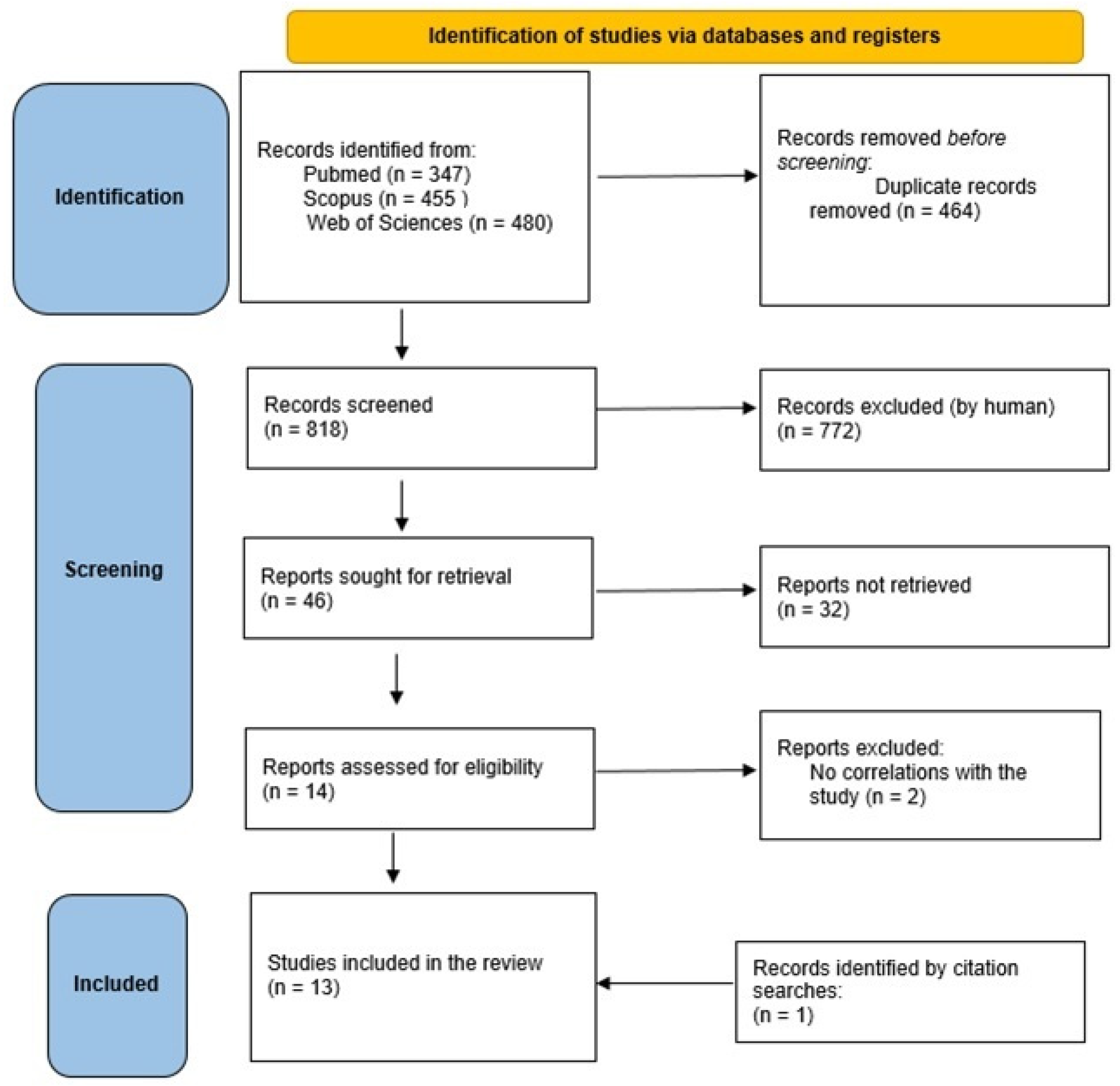

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Relevant Research

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Description of Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Non Communicable Diseases (NCD). 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/mortality_morbidity/en/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Tan, M.M.J.; Han, E.; Shrestha, P.; Wu, S.; Shiraz, F.; Koh, G.C.; McKee, M.; Legido-Quigley, H. Framing global discourses on non-communicable diseases: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Smith, G.D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean diet pyramid: A cultural model for healthy eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; de la Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Nunez-Córdoba, J.M.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Beunza, J.J.; Vazquez, Z.; Benito, S.; Tortosa, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2008, 336, 1348–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benetou, V.; Trichopoulou, A.; Orfanos, P. Conformity to traditional Mediterranean diet and cancer incidence: The Greek EPIC cohort. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffond, A.; Rivera-Picón, C.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, P.M.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Ruiz de Viñaspre-Hernández, R.; Navas-Echazarreta, N.; Sánchez-González, J.L. Mediterranean Diet for Primary and Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: An Updated Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meslier, V.; Laiola, M.; Roager, H.M.; De Filippis, F.; Roume, H.; Quinquis, B.; Giacco, R.; Mennella, I.; Ferracane, R.; Pons, N.; et al. Mediterranean diet intervention in overweight and obese subjects lowers plasma cholesterol and causes changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome independently of energy intake. Gut 2020, 69, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alberti-Fidanza, A.; Fidanza, F. Mediterranean Adequacy Index of Italian diets. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Mediterranean Diet. 2010. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Keys, A. Mediterranean diet and public health: Personal reflections. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1321S–1323S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, E.; Ferro, Y.; Pujia, R.; Mare, R.; Maurotti, S.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A. Mediterranean Diet In Healthy Aging. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCSE). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/the-heavy-burden-of-obesity-67450d67-en.htm (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- ATLAS. Word Obesity Atlas. 2023. Available online: https://www.worldobesity.org/resources/resource-library/world-obesity-atlas-2023 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Gualtieri, P.; Marchetti, M.; Frank, G.; Cianci, R.; Bigioni, G.; Colica, C.; Soldati, L.; Moia, A.; De Lorenzo, A.; Di Renzo, L. Exploring the Sustainable Benefits of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy. Nutrients 2022, 15, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Saulle, R.; Semyonov, L.; La Torre, G. Cost and cost-effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet: Results of a systematic review. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4566–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. 2011. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Modesti, P.A.; Reboldi, G.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Agyemang, C.; Remuzzi, G.; Rapi, S.; Perruolo, E.; Parati, G.; Okechukwu, O.S. Panethnic Differences in Blood Pressure in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (adapted for cross sectional studies) (S1 Text). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appendix: Jadad Scale for Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials. In Evidence-Based Obstetric Anesthesia; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 237–238. [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Nicolotti, N.; de Waure, C.; Ricciardi, W. Development of a weighted scale to assess the quality of cost-effectiveness studies and an application to the economic evaluations of tetravalent HPV vaccine. J. Public Health 2011, 19, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, J.; Turbett, E.; Mckevic, A.; Rudgard, K.; Hearth, H.; Mathers, J.C. The Mediterranean diet among British older adults: Its understanding, acceptability and the feasibility of a randomised brief intervention with two levels of dietary advice. Maturitas 2015, 82, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.P.H.; Abdullah, M.M.H.; Wood, D.; Jones, P.J.H. Economic modeling for improved prediction of saving estimates in healthcare costs from consumption of healthy foods: The Mediterranean-style diet case study. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lampropoulos, C.E.; Konsta, M.; Dradaki, V.; Roumpou, A.; Dri, I.; Papaioannou, I. Effects of Mediterranean diet on hospital length of stay, medical expenses, and mortality in elderly, hospitalized patients: A 2-year observational study. Nutrition 2020, 79, 110868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, L.; Twizeyemariya, A.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Niyonsenga, T.; Bogomolova, S.; Wilson, A.; O’Dea, K.; Parletta, N. Cost effectiveness and cost-utility analysis of a group-based diet intervention for treating major depression-the HELFIMED trial. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seconda, L.; Baudry, J.; Allès, B.; Hamza, O.; Boizot-Szantai, C.; Soler, L.G.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Lairon, D.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Assessment of the Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet Combined with Organic Food Consumption: An Individual Behaviour Approach. Nutrients 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tong, T.Y.N.; Imamura, F.; Monsivais, P.; Brage, S.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Dietary cost associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and its variation by socio-economic factors in the UK Fenland Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yacoub Bach, L.; Jana, B.E.; Adaeze Egwatu, C.F.; Orndor, C.J.; Alanakrih, R.; Okoro, J.; Gahl, M.K. A sustainability analysis of environmental impact, nutritional quality, and price among six popular diets. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1021906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, A.C.; Sapin, A.; Monlezun, D.J.; McCormack, I.G.; Latoff, A.; Pedroza, K.; McCullough, C.; Sarris, L.; Schlag, E.; Dyer, A.; et al. Effect of culinary education curriculum on Mediterranean diet adherence and food cost savings in families: A randomised controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 2297–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schepers, J.; Annemans, L. The potential health and economic effects of plant-based food patterns in Belgium and the United Kingdom. Nutrition 2018, 48, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, H.; Gomez, S.F.; Ribas-Barba, L.; Pérez-Rodrigo, C.; Bawaked, R.A.; Fíto, M.; Serra-Majem, L. Monetary Diet Cost, Diet Quality, and Parental Socioeconomic Status in Spanish Youth. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schröder, H.; Serra-Majem, L.; Subirana, I.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M.; Fitó, M.; Elosua, R. Association of increased monetary cost of dietary intake, diet quality and weight management in Spanish adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor, R.; Pinilla, N.; Tur, J.A. The Economic Cost of Diet and Its Association with Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in a Cohort of Spanish Primary Schoolchildren. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pedroni, C.; Castetbon, K.; Desbouys, L.; Rouche, M.; Vandevijvere, S. The Cost of Diets According to Nutritional Quality and Sociodemographic Characteristics: A Population-Based Assessment in Belgium. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 2187–2200.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubini, A.; Vilaplana-Prieto, C.; Flor-Alemany, M.; Yeguas-Rosa, L.; Hernández-González, M.; Félix-García, F.J.; Félix-Redondo, F.J.; Fernández-Bergés, D. Assessment of the Cost of the Mediterranean Diet in a Low-Income Region: Adherence and Relationship with Available Incomes. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 58, Erratum in BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tharrey, M.; Maillot, M.; Azaïs-Braesco, V.; Darmon, N. From the SAIN, LIM system to the SENS algorithm: A review of a French approach of nutrient profiling. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| References | Study Design | Type of Analyses | Diseases Outcomes | Alternatives | Nation/Perspective | Sample | Efficacy Measures/ Cost Measures | Main Results | QA (NOS) or (RCT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lara et al., 2015 [22] | RCT | Cost of the diet | No | Evaluation of the comprehension, acceptability, feasibility, adherence, and cost of the DM in an elderly population | England/elderly population | 23 healthy men and women aged 50 and over | Direct Costs | The average daily cost of food intake, estimated from the 3-day food diaries, was not significantly different between pre- and post-intervention for group 1, group 2, or the combined sample. The daily food cost was not significantly different between groups 1 and 2. Linear regression analysis showed that a one-point increase in the DM score represented a cost of 0.55 pounds. Furthermore, participants were asked to report their perception of any difference in the cost of their diet before and after the intervention. Compared to the perceived cost of their usual diet before the intervention, the vast majority (87%) of participants reported that the perceived cost of their diet after 3 weeks of intervention was less than or equal to that of their usual diet. | 4 |

| Jones et al., 2019 [23] | Cost-of-illness analysis | Economic evaluation | CVD | Direct and indirect economic advantages of high adherence to DM over CVD | Canada/United States | No | Cost of illness | Increasing the proportion of the population adhering to DM by 20% above the current level of adherence resulted in annual savings in CVD-related costs of USD 8.2 billion (95% confidence interval [CI]: USD 7.5–8.8 billion) in the United States and CAD 0.32 billion (95% CI: CAD 0.29–0.34 billion) in Canada. An 80% increase in adherence resulted in savings of USD 31 billion (95% CI: USD 28.6–33.3 billion) and CAD 1.2 billion (95% CI: CAD 1.11–1.30 billion) in each country. | |

| Lampropoulos et al., 2020 [24] | Cost-of-illness analysis | Evaluation of dietary adherence effectiveness | Length of hospital stay | Economic advantages over hospitalization of patients with high DM adherence | Greece | 183 | Hospitalization costs | The length of hospital stay decreased by 0.3 days for each unit increase in the DM score (p < 0.0001), by 2.1 days for each 1 g/dL increase in albumin (p = 0.001) and by 0.1 days for each day of previous hospitalization (p < 0.0001). Prolonged hospitalization (p < 0.0001) and its interaction with DM score (p = 0.01) remained the significantly associated variables for financial cost. Mortality risk increased by 3% for each year of age increase (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03; p = 0.02) and 6% for each previous admission (HR, 1.06; p = 0.04), and decreased by 13% for each unit of DM score increase (HR, 0.87; p < 0.0001). | 9 |

| Segal et al., 2020 [25] | Economic evaluation | Utility and cost-effectiveness analysis of the dietary intervention | Depression | Utility and cost-effectiveness analysis of a Mediterranean dietary intervention in the treatment of depression | Australia | 152 |

| An intervention that implemented the DM (including cooking workshops) in persons diagnosed with major depression was found to be extremely cost-effective in curing the condition compared to a group in which the intervention was based on social activities. | |

| Seconda et al., 2017 [26] | Cohort | Utility and cost-effectiveness analysis of different dietary models | No | Comparison of four dietary models assessing Mediterranean adherence, sustainability, health, and cost | France | 22,866 | Direct/indirect costs | This study showed that sustainability indicators related to health and nutrition, environmental impact, and sustainability for purchasing and sociocultural aspects were consistently better among Conv-Med, Org-NoMed, or Org-Med participants than among Conv-NoMed participants. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the combination of both the DM and the high consumption of organic food (Org-Med group) was associated with better values of the indicators related to sustainability, apart from the cost of the diet. | 6 |

| Tong et al., 2018 [27] | Cohort | Cost of the diet | No | Association between diet cost and adherence to the DM in a non-Mediterranean country | England | 12,435 | Direct costs | High adherence to the DM was associated with higher dietary costs. On average, high adherence to the DM (mean dietary cost: GBP 4.47, 95% CI 4.44, 4.49) was associated with a price difference of GBP 0.20 per day (95% CI 0.16, 0.24) compared to low adherence (GBP 4.26, 95% CI 4.23, 4.29), equivalent to 5.4% (95% CI 4.4, 6.4) | 3 |

| Yacoub Bach et al., 2023 [28] | Observational study | Cost and dietary sustainability | No | Analysis of sustainability, nutritional quality, and cost among different diets | N/A | No |

| The study shows that vegan, Mediterranean, and vegetarian diets are the most sustainable in all parameters, while diets rich in meat have the greatest negative environmental impact. Diets based on WHO dietary guidelines performed poorly in terms of convenience, environmental impact, and nutritional quality. Diets with higher nutritional quality included the vegan, paleo, and DM. Diets that eliminated meat were the cheapest in terms of both total cost and cost per gram of food. | / |

| Razavi et al., 2020 [29] | RCT | Cost and environmental sustainability of the diet | No | Effects of a culinary education program on diet cost and adherence to the DM | United States | 41 families | Direct costs | Households participating in hands-on kitchen-based nutrition education were almost three times more likely to follow a Mediterranean dietary pattern (OR 2–93, 95% CI 1–73, 4–95; p < 0.001), with a 0.43 point increase in adherence to the DM after 6 weeks (B = 0.43; p < 0.001), compared to those with traditional nutrition counseling. Furthermore, kitchen-based nutrition education projects saved families USD 21.70 per week compared to standard dietary counseling, increasing the likelihood of eating home-prepared meals compared to commercially prepared meals (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.08, 2–25; p = 0–018). | 2 |

| Schepers and Annemans 2018 [30] | Prediction model study | Cost-effectiveness analysis | Chronic Diseases | Evaluation of health and economic effects of plant-based diets | Belgium/England | 1000 men and 1000 women | Direct/indirect costs | Based on the study’s model, if 10% of the total population were to strongly commit to the DM, the social cost savings in Belgium and the UK over 20 years would be estimated at EUR 1.55 billion and GBP 7.53 billion, respectively. | / |

| Schröder et al., 2016 [31] | Cross-sectional | Cost of the diet | No | Relationships between diet cost, socioeconomic status, and adherence to the Mediterranean model (students) | Spain | 1629 boys and 1905 girls | Direct costs | Socioeconomic status was positively associated with daily diet cost and diet quality as measured by the KIDMED index (EUR/day and EUR/1000 kcal/day, p < 0.019). High adherence to the DM (KIDMED score 8–12) was EUR 0.71/day (EUR 0.28/1000 kcal/day) more expensive than low adherence (KIDMED score 0–3). The higher daily cost of diet is associated with healthy eating in young Spaniards. Higher socioeconomic status is a determinant factor for higher daily diet cost and quality. | 8 |

| Schröder et al., 2021 [32] | Prospective, population-based study | Cost of the diet | Obesity and overweight | Relationship between diet cost, food quality, and weight loss (adults) | Spain | 2181 | Direct costs | The average daily diet cost increased from 3.68 (SD 0.89) EUR/8.36 MJ to 4.97 (SD 1.16) EUR/8.36 MJ during the study period. This increase was significantly associated with improved diet quality (Δ ED and Δ DMS-rec; p < 0–0001). Each EUR 1 increase in the monetary cost of the diet per 8.36 MJ was associated with a 0.3 kg decrease in body weight (p = 0.02) and 0.1 kg/m2 in BMI (p = 0.02). An improvement in diet quality and better weight management were both associated with an increase in diet cost | 9 |

| Pastor et al., 2021 [33] | Cross-sectional | Cost of the diet | No | Relationship between cost and diet quality (children) | Spain | 130 children | Direct costs | A direct relationship was observed between diet cost and DM adherence [OR (EUR/1000 kcal/day) = 3.012; CI (95%): 1.291; 7.026; p = 0.011]. It should be noted that the cohort examined had low overall adherence to the DM. | 8 |

| Pedroni et al., 2021 [34] | Cross-sectional | Cost of the diet | No | Cost differences between different dietary quality and sociodemographic characteristics | Belgium | 1158 | Direct costs | The mean cost of the daily diet was USD 6.51 (standard error of the mean [SEM] USD 0.08; EUR 5.79 [EUR 0.07]). Adjusted for covariates and energy intake, the mean daily diet cost (SEM) was significantly higher in the highest tercile (T3) of both diet quality scores compared to T1 (DM score: T1 = USD 6.29 [USD 0.10]; EUR 5.60 [EUR 0.09] vs. T3 = USD 6.78 [USD 0.11]; EUR 6.03 [EUR 0.10]; Healthy Diet Indicator: T1 = USD 6.09 [USD 0.10]; EUR 5.42 [EUR 0.09] vs. T3 = USD 7.13 [USD 0.11]; EUR 6.34 [EUR 0.10]). Both diet quality and cost were higher in respondents aged 35–64 (compared to those aged 18–34), working (compared to students), and those with higher levels of education. The association between quality and cost of diets was weaker in men and among those with higher levels of education. | 9 |

| Rubini et al., 2022 [35] | Cohort | Cost of the diet | No | Cost and adherence to the Mediterranean model in a low-income region | Spain | 2833 | Direct costs | The average monthly cost was EUR 203.6 (IQR: 154.04–265.37). Food expenditure was higher for men (p < 0.001), for the 45–54 age group (p < 0.013), and for those living in urban areas (p < 0.001). A positive correlation was found between food-related expenditure and adherence to the DM. The median monthly cost represented 15% of the mean disposable income, varying between 11% for the group with low adherence to the DM and 17% for the group with high adherence to the DM. The monthly cost of the DM was positively correlated with the degree of adherence to this dietary pattern. | 3 |

| Gualtieri et al., 2023 [15] | Cross-sectional | Cost and environmental sustainability of the diet | No | Adherence to the DM and its effect on health and environmental and socioeconomic sustainability during the COVID-19 pandemic in an Italian population sample | Italy | 3353 |

| The low and medium adherence groups showed higher CO2 and a higher H2O emissions than the high adherence group (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, the medium adherence group had higher CO and higher H2O than the low adherence group (p < 0.001). In addition, a lower BMI was associated with a decrease in CO2 and H2O emissions. Food costs resulted in statistically significant differences between the MEDAS groups. In fact, the high adherence group had a lower weekly food cost than the low and medium adherence groups (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively), and the medium adherence group had a lower weekly food cost than the low adherence group (p = 0.004). | 10 |

| Authors (Year of Publication) | Schepers and Annemans 2018 [30] | Segal et al., 2020 [25] | Jones et al., 2019 [23] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study design Score/items (25 score items) | 23/25 | 24/25 | 16/25 |

| Data collection Score/items (46 score items) | 36/46 | 35/46 | 45/46 |

| Analysis and interpretations of results Score/items (45 score items) | 36/45 | 45/46 | 36/45 |

| Total score/items | 95/116 = 81.89% | 104/116 = 89.65% | 97/116 = 83.62% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Colaprico, C.; Crispini, D.; Rocchi, I.; Kibi, S.; De Giusti, M.; La Torre, G. Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet: An Update of a Systematic Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121899

Colaprico C, Crispini D, Rocchi I, Kibi S, De Giusti M, La Torre G. Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet: An Update of a Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2024; 16(12):1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121899

Chicago/Turabian StyleColaprico, Corrado, Davide Crispini, Ilaria Rocchi, Shizuka Kibi, Maria De Giusti, and Giuseppe La Torre. 2024. "Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet: An Update of a Systematic Review" Nutrients 16, no. 12: 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121899

APA StyleColaprico, C., Crispini, D., Rocchi, I., Kibi, S., De Giusti, M., & La Torre, G. (2024). Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of the Mediterranean Diet: An Update of a Systematic Review. Nutrients, 16(12), 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16121899