Examining the Direct and Indirect Effects of Postprandial Amino Acid Responses on Markers of Satiety following the Acute Consumption of Lean Beef-Rich Meals in Healthy Women with Overweight

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Dietary Pattern

2.4. Clinical Testing Day

2.5. Repeated Blood Sampling and Plasma Analyses

2.6. Data and Statistical Analyses

3. Results

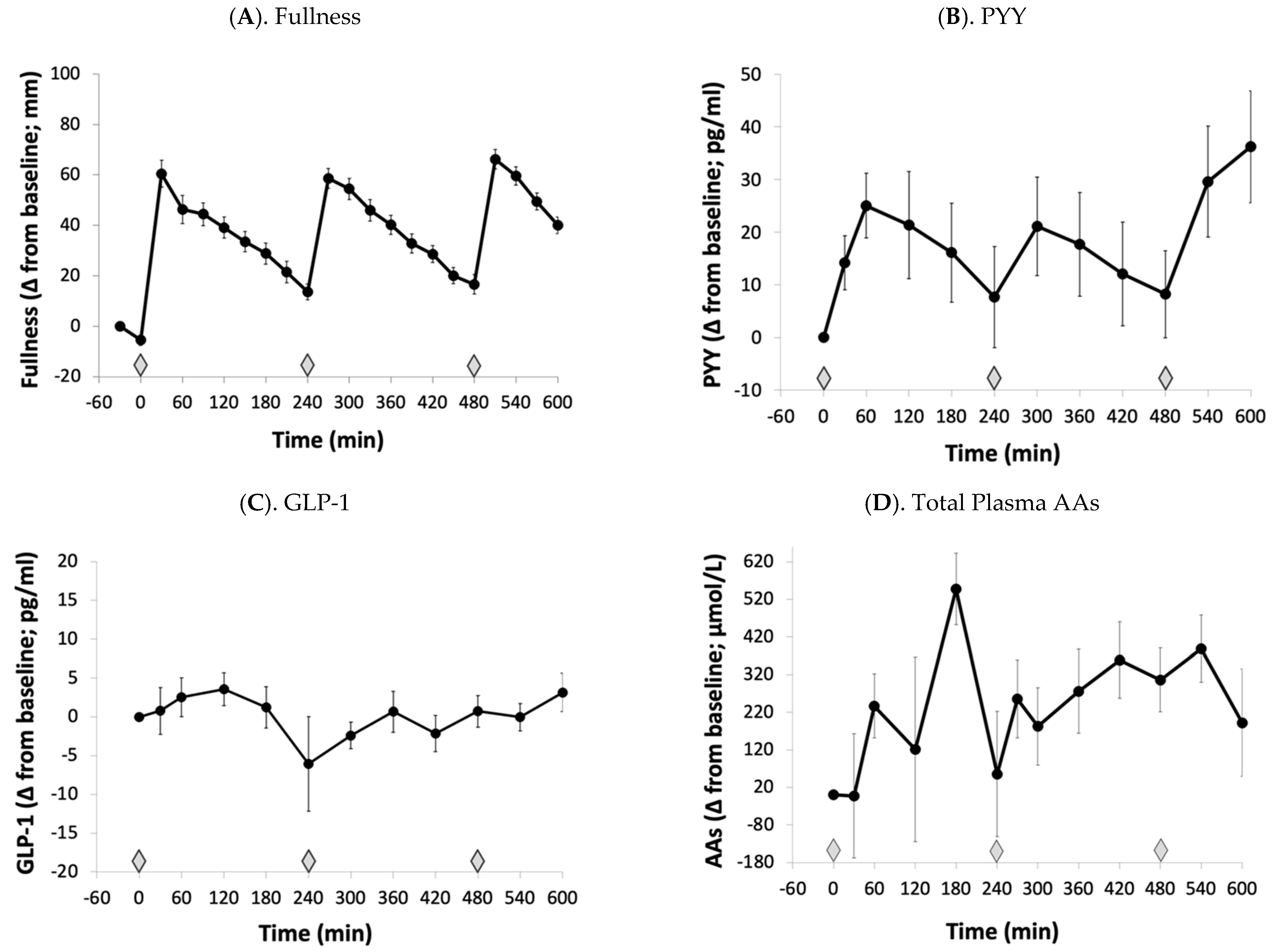

3.1. Amino Acid and Satiety Profiles

3.2. Amino Acid Predictors

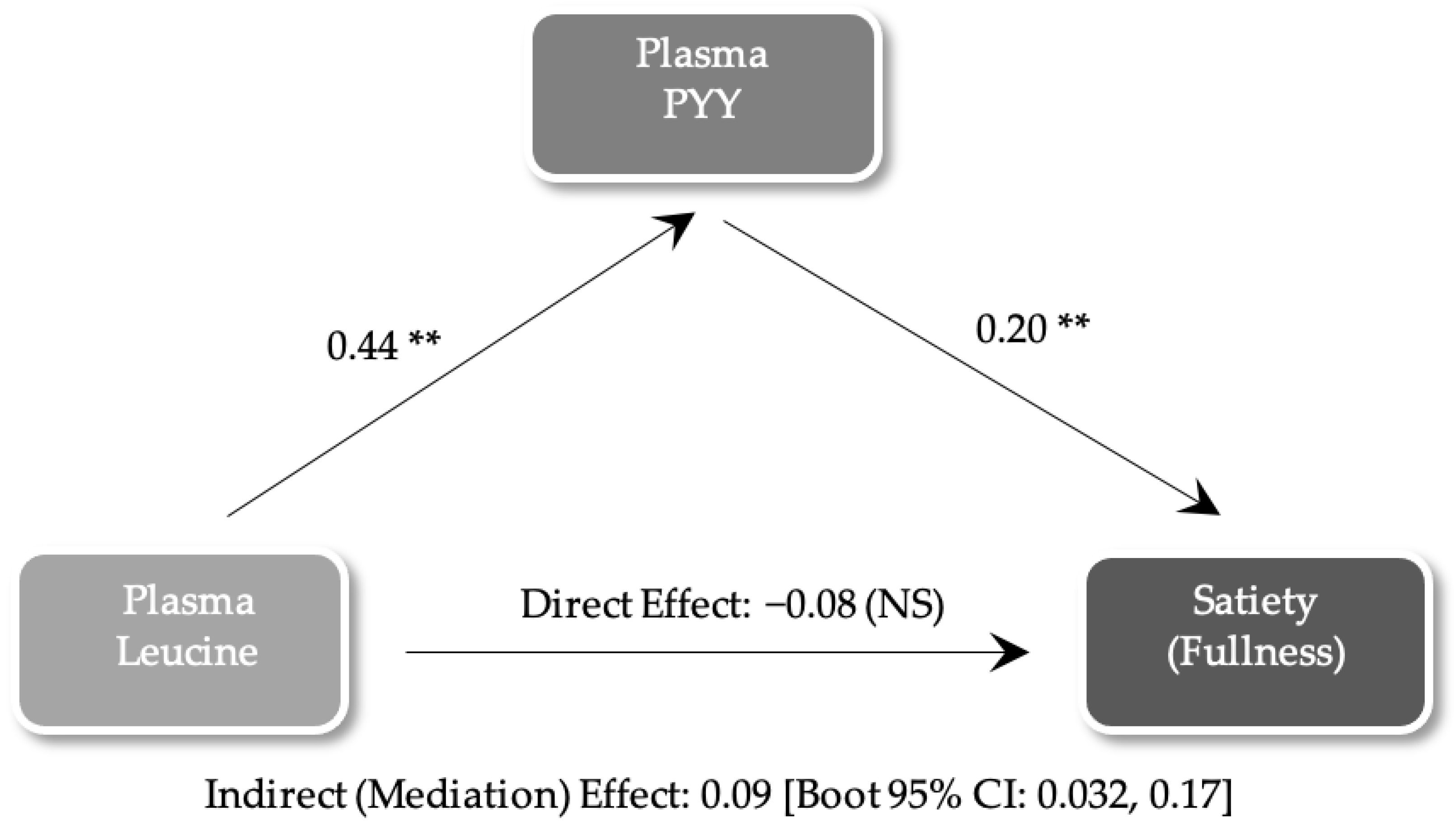

3.3. Mediation Analyses

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blundell, J.; De Graaf, C.; Hulshof, T.; Jebb, S.; Livingstone, B.; Lluch, A.; Mela, D.; Salah, S.; Schuring, E.; Van Der Knaap, H.; et al. Appetite Control: Methodological Aspects of the Evaluation of Foods Europe. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidy, H.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Astrup, A.; Wycherley, T.P.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Luscombe-Marsh, N.D.; Woods, S.C.; Mattes, R.D. The Role of Protein in Weight Loss and Maintenance 1-5. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; Lemmens, S.G.; Westerterp, K.R. Dietary Protein—Its Role in Satiety, Energetics, Weight Loss and Health. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S105–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Journel, M.; Chaumontet, C.; Darcel, N.; Fromentin, G.; Tomé, D. Brain Responses to High-Protein Diets. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, K.S.; Shearrer, G.E.; Gilbert, J.R. Brain, Environment, Hormone Based Appetite, Ingestive Behavior, and Body Weight. In Textbook of Energy Balance, Neuropeptide Hormones, and Neuroendocrine Function; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9783319895062. [Google Scholar]

- Tomé, D.; Schwarz, J.; Darcel, N.; Fromentin, G. Protein, Amino Acids, Vagus Nerve Signaling, and the Brain. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 838S–843S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, U. Protein-Induced Satiation and the Calcium-Sensing Receptor. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2018, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonson, M.; Boirie, Y.; Guillet, C. Protein, Amino Acids and Obesity Treatment. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Xu, C.; Navarro, M.; Masiques, N.E.; Tilbrook, A.; Van Barneveld, R.; Roura, E. Leucine (and Lysine) Increased Plasma Levels of the Satiety Hormone Cholecystokinin (CCK), and Phenylalanine of the Incretin Glucagon-like Peptide 1 (GLP-1) after Oral Gavages in Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamshah, A.; Mcgavigan, A.K.; Spreckley, E.; Kinsey-Jones, J.S.; Amin, A.; Tough, I.R.; O’hara, H.C.; Moolla, A.; Banks, K.; France, R.; et al. L-Arginine Promotes Gut Hormone Release and Reduces Food Intake in Rodents. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, C.; Smajilovic, S.; Smith, E.P.; Woods, S.C.; Bräuner-Osborne, H.; Seeley, R.J.; D’Alessio, D.A.; Ryan, K.K. Oral L-Arginine Stimulates GLP-1 Secretion to Improve Glucose Tolerance in Male Mice. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3978–3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Tough, I.R.; Cox, H.M. Endogenous PYY and GLP-1 Mediate l -Glutamine Responses in Intestinal Mucosa. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 170, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, T.; Ito, Y.; Nishizawa, N.; Nagasawa, T. Regulation of Muscle Protein Degradation, Not Synthesis, by Dietary Leucine in Rats Fed a Protein-Deficient Diet. Amino Acids 2009, 37, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananieva, E.A.; Powell, J.D.; Hutson, S.M. Leucine Metabolism in T Cell Activation: MTOR Signaling and Beyond. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 798S–805S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.J.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.X.; Jiao, H.C.; Zhao, J.P.; Song, Z.G.; Lin, H. Leucine Alleviates Dexamethasone-Induced Suppression of Muscle Protein Synthesis via Synergy Involvement of MTOR and AMPK Pathways. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.; Knowles, S.; Bermingham, E.; Brown, J.; Hannaford, R.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Braakhuis, A. Plasma Amino Acid Appearance and Status of Appetite Following a Single Meal of Red Meat or a Plant-Based Meat Analog: A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022, 6, nzac082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigamonti, A.E.; Leoncini, R.; De Col, A.; Tamini, S.; Cicolini, S.; Abbruzzese, L.; Cella, S.G.; Sartorio, A. The Appetite-Suppressant and GLP-1-Stimulating Effects of Whey Proteins in Obese Subjects Are Associated with Increased Circulating Levels of Specific Amino Acids. Nutrients 2020, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhe, A.M.; Collier, G.R.; O’Dea, K. A Comparison of the Effects of Beef, Chicken and Fish Protein on Satiety and Amino Acid Profiles in Lean Male Subjects. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwin, J.A.; Maki, K.C.; Alwattar, A.Y.; Leidy, H.J. Examination of Protein Quantity and Protein Distribution across the Day on Ad Libitum Carbohydrate and Fat Intake in Overweight Women. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e001933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781609182304. [Google Scholar]

- Wycherley, T.P.; Moran, L.J.; Clifton, P.M.; Noakes, M.; Brinkworth, G.D. Effects of Energy-Restricted High-Protein, Low-Fat Compared with Standard-Protein, Low-Fat Diets: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 1320S–1329S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.T.; Astrup, A.; Sjödin, A. Are Dietary Proteins the Key to Successful Body Weight Management? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Assessing Body Weight Outcomes after Interventions with Increased Dietary Protein. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, J.; Craig, B.A.; Leidy, H.J.; Amankwaah, A.F.; Osei-Boadi Anguah, K.; Jacobs, A.; Jones, B.L.; Jones, J.B.; Keeler, C.L.; Keller, C.E.M.; et al. The Effects of Increased Protein Intake on Fullness: A Meta-Analysis and Its Limitations. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 968–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolster, D.R.; Rahn, M.; Kamil, A.G.; Bristol, L.T.; Goltz, S.R.; Leidy, H.J.; Melvin Blaze, M.T.; Nunez, M.A.; Guo, E.; Wang, J.; et al. Consuming Lower-Protein Nutrition Bars with Added Leucine Elicits Postprandial Changes in Appetite Sensations in Healthy Women. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanni, A.E.; Kokkinos, A.; Binou, P.; Papaioannou, V.; Halabalaki, M.; Konstantopoulos, P.; Simati, S.; Karathanos, V.T. Postprandial Glucose and Gastrointestinal Hormone Responses of Healthy Subjects to Wheat Biscuits Enriched with L-Arginine or Branched-Chain Amino Acids of Plant Origin. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlick, P.J. The Role of Leucine in the Regulation of Protein Metabolism. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1553S–1556S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed.; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Wolfe, R.R.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Kim, I.Y.; Moughan, P.J. Protein Quality as Determined by the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score: Evaluation of Factors Underlying the Calculation. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, R.R.; Baum, J.I.; Starck, C.; Moughan, P.J. Factors Contributing to the Selection of Dietary Protein Food Sources. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, A.; Bellisle, F. Nutrients, Satiety, and Control of Energy Intake. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarroso, N.A.; Fuciños, P.; Gonçalves, C.; Pastrana, L.; Amado, I.R. A Review on the Role of Food-Derived Bioactive Molecules and the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Satiety Regulation. Nutrients 2021, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moris, J.M.; Heinold, C.; Blades, A.; Koh, Y. Nutrient-Based Appetite Regulation. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2022, 31, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fullness | Plasma AA | B | SE B | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glutamate | −0.81 | 0.150 | −0.51 | −0.542 | 0.589 | |

| asparagine | 0.838 | 0.245 | 0.187 | 1.565 | 0.120 | |

| serine | 0.520 | 0.175 | 0.416 | 2.969 | 0.003 * | |

| glutamine | −0.008 | 0.041 | −0.022 | −0.205 | 0.838 | |

| histidine | −0.340 | 0.317 | −0.152 | −1.071 | 0.286 | |

| glycine | −0.119 | 0.041 | −0.373 | −2.906 | 0.004 * | |

| threonine | 0.140 | 0.123 | −0.152 | 1.134 | 0.259 | |

| citrulline | 0.165 | 0.578 | 0.035 | 0.285 | 0.776 | |

| arginine | −0.148 | 0.187 | −0.133 | 0.792 | 0.429 | |

| alanine | 0.167 | 0.033 | 0.504 | 5.001 | <0.001 * | |

| tyrosine | 0.266 | 0.416 | 0.082 | 0.639 | 0.524 | |

| cystine | −0.695 | 0.429 | −0.330 | −1.619 | 0.107 | |

| valine | 0.078 | 0.222 | 0.086 | 0.352 | 0.726 | |

| methionine | −2.716 | 0.917 | −0.458 | −2.963 | 0.004 * | |

| phenylalanine | 1.216 | 0.716 | 0.367 | 1.699 | 0.091 | |

| isoleucine | 0.437 | 0.433 | 0.192 | 1.011 | 0.314 | |

| leucine | −0.140 | 0.443 | −0.096 | −0.316 | 0.752 | |

| lysine | −0.146 | 0.129 | −0.195 | −1.132 | 0.259 | |

| R2 = 0.411 F (18,159) = 6.170 | ||||||

| PYY | Plasma AA | B | SE B | β | t | p |

| glutamate | 0.748 | 23.340 | 0.370 | 4.418 | 0.000 * | |

| asparagine | 0.771 | 0.169 | 0.297 | 2.906 | 0.004 * | |

| serine | −0.632 | 0.265 | −0.393 | −3.233 | 0.002 * | |

| glutamine | 0.011 | 0.195 | 0.023 | 0.250 | 0.803 | |

| histidine | 0.874 | 0.046 | 0.307 | 2.527 | 0.013 * | |

| glycine | 0.075 | 0.346 | 0.183 | 1.669 | 0.097 | |

| threonine | 0.105 | 0.045 | 0.094 | 0.776 | 0.439 | |

| citrulline | 0.405 | 0.135 | 0.067 | 0.640 | 0.523 | |

| arginine | 0.170 | 0.633 | 0.117 | 0.808 | 0.420 | |

| alanine | 0.192 | 0.210 | 0.453 | 5.348 | 0.000 * | |

| tyrosine | −1.521 | 0.036 | −0.362 | −3.276 | 0.001 * | |

| cystine | −2.479 | 0.464 | −0.916 | −5.141 | 0.000 * | |

| valine | −0.475 | 0.482 | −0.397 | −1.956 | 0.052 | |

| methionine | −1.347 | 0.243 | −0.177 | −1.321 | 0.189 | |

| phenylalanine | 3.933 | 1.020 | 0.916 | 4.806 | 0.000 * | |

| isoleucine | −0.883 | 0.818 | −0.295 | −1.808 | 0.073 | |

| leucine | 1.230 | 0.489 | 0.639 | 2.565 | 0.011 * | |

| lysine | −0.318 | 0.480 | −0.327 | −2.223 | 0.028 * | |

| R2 = 0.610 F (18,145) = 12.578 | ||||||

| GLP-1 | Plasma AA | B | SE B | β | t | p |

| glutamate | 0.453 | 0.111 | 0.319 | 4.069 | 0.000 * | |

| asparagine | −0.792 | 0.175 | −0.431 | −4.514 | 0.000 * | |

| serine | −0.460 | 0.129 | −0.407 | −3.579 | 0.000 * | |

| glutamine | 0.184 | 0.030 | 0.533 | 6.139 | 0.000 * | |

| histidine | −0.317 | 0.227 | −0.157 | −1.394 | 0.166 | |

| glycine | 0.124 | 0.030 | 0.429 | 4.180 | 0.000 * | |

| threonine | 0.409 | 0.089 | 0.523 | 4.616 | 0.000 * | |

| citrulline | −0.742 | 0.416 | −0.174 | −1.786 | 0.076 | |

| arginine | −0.414 | 0.138 | −0.407 | −3.003 | 0.003 * | |

| alanine | 0.061 | 0.024 | 0.205 | 2.587 | 0.011 * | |

| tyrosine | 0.425 | 0.305 | 0.144 | 1.395 | 0.165 | |

| cystine | −0.884 | 0.317 | −0.463 | −2.788 | 0.006 * | |

| valine | 0.285 | 0.160 | 0.340 | 1.787 | 0.076 | |

| methionine | 1.789 | 0.670 | 0.335 | 2.670 | 0.008 * | |

| phenylalanine | −0.191 | 0.540 | −0.063 | −0.353 | 0.724 | |

| isoleucine | 0.647 | 0.322 | 0.307 | 2.010 | 0.046 | |

| leucine | −0.815 | 0.316 | −0.602 | −2.584 | 0.011 * | |

| lysine | 0.051 | 0.095 | 0.074 | 0.539 | 0.591 | |

| R2 = 0.661 F (18,144) = 15.630 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Braden, M.L.; Gwin, J.A.; Leidy, H.J. Examining the Direct and Indirect Effects of Postprandial Amino Acid Responses on Markers of Satiety following the Acute Consumption of Lean Beef-Rich Meals in Healthy Women with Overweight. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111718

Braden ML, Gwin JA, Leidy HJ. Examining the Direct and Indirect Effects of Postprandial Amino Acid Responses on Markers of Satiety following the Acute Consumption of Lean Beef-Rich Meals in Healthy Women with Overweight. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111718

Chicago/Turabian StyleBraden, Morgan L., Jess A. Gwin, and Heather J. Leidy. 2024. "Examining the Direct and Indirect Effects of Postprandial Amino Acid Responses on Markers of Satiety following the Acute Consumption of Lean Beef-Rich Meals in Healthy Women with Overweight" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111718

APA StyleBraden, M. L., Gwin, J. A., & Leidy, H. J. (2024). Examining the Direct and Indirect Effects of Postprandial Amino Acid Responses on Markers of Satiety following the Acute Consumption of Lean Beef-Rich Meals in Healthy Women with Overweight. Nutrients, 16(11), 1718. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111718