Early Enteral Nutrition (within 48 h) for Patients with Sepsis or Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

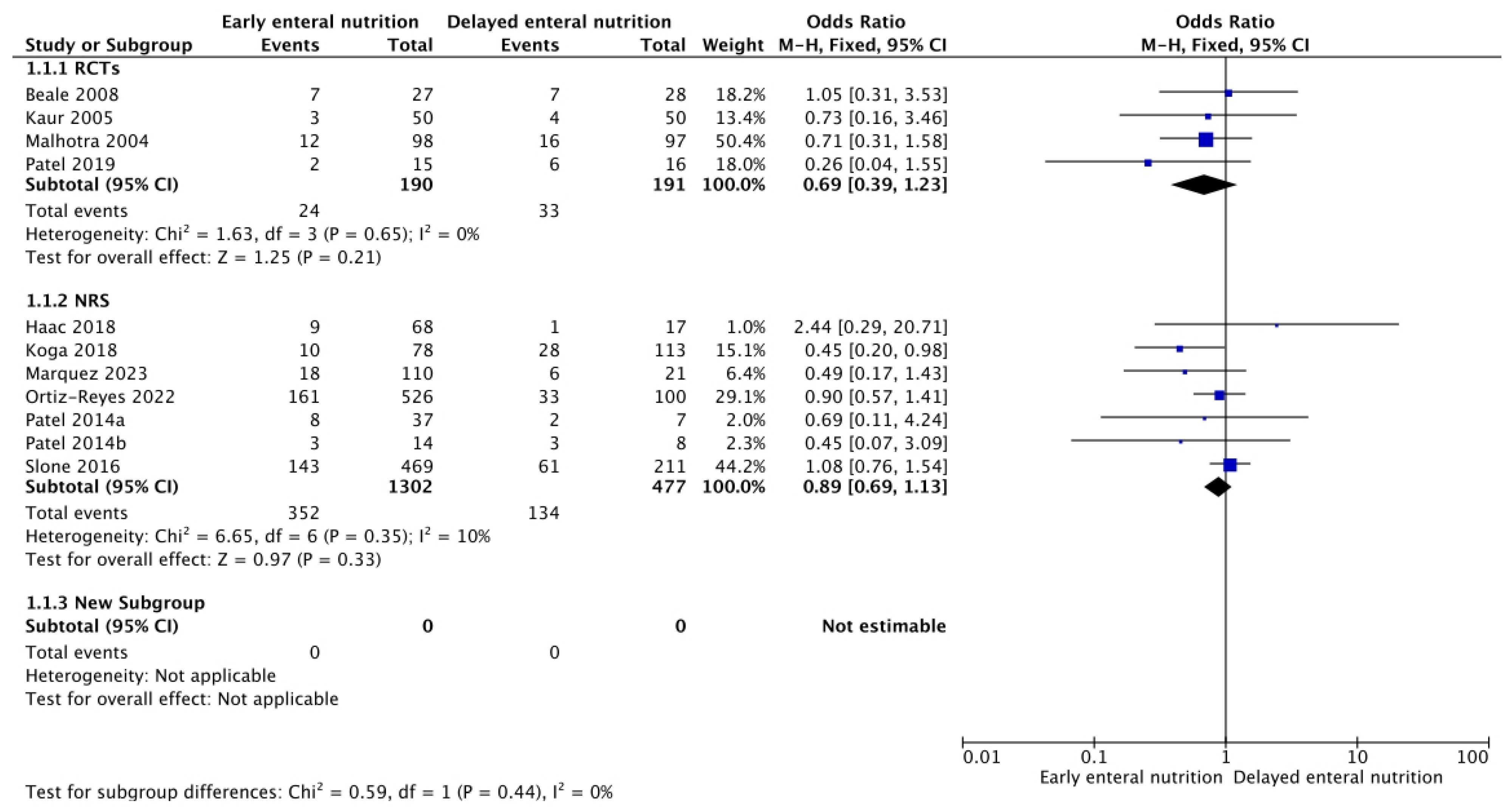

3.1. In-Hospital, 28-, and 90-Day Mortality

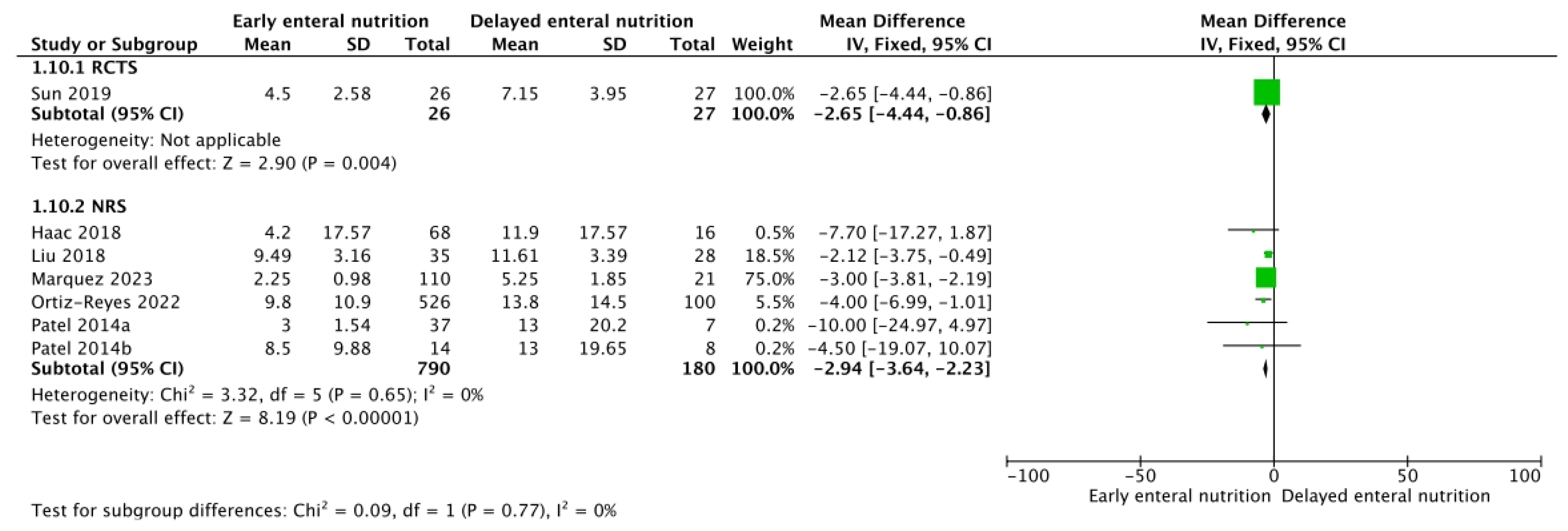

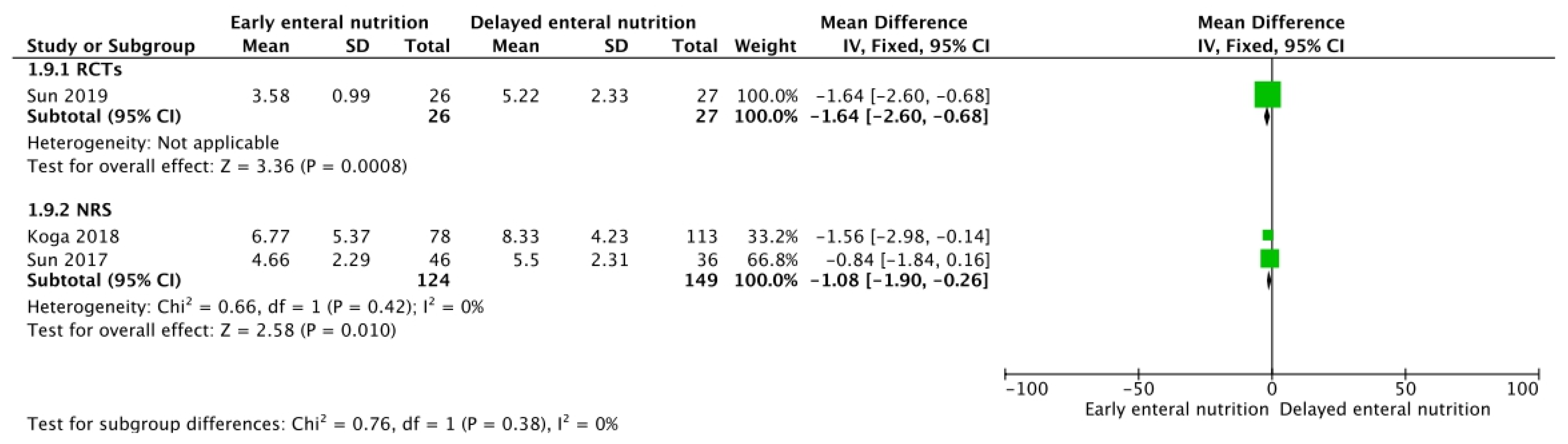

3.2. Mechanical Ventilation, Renal Replacement Therapy, and SOFA Score

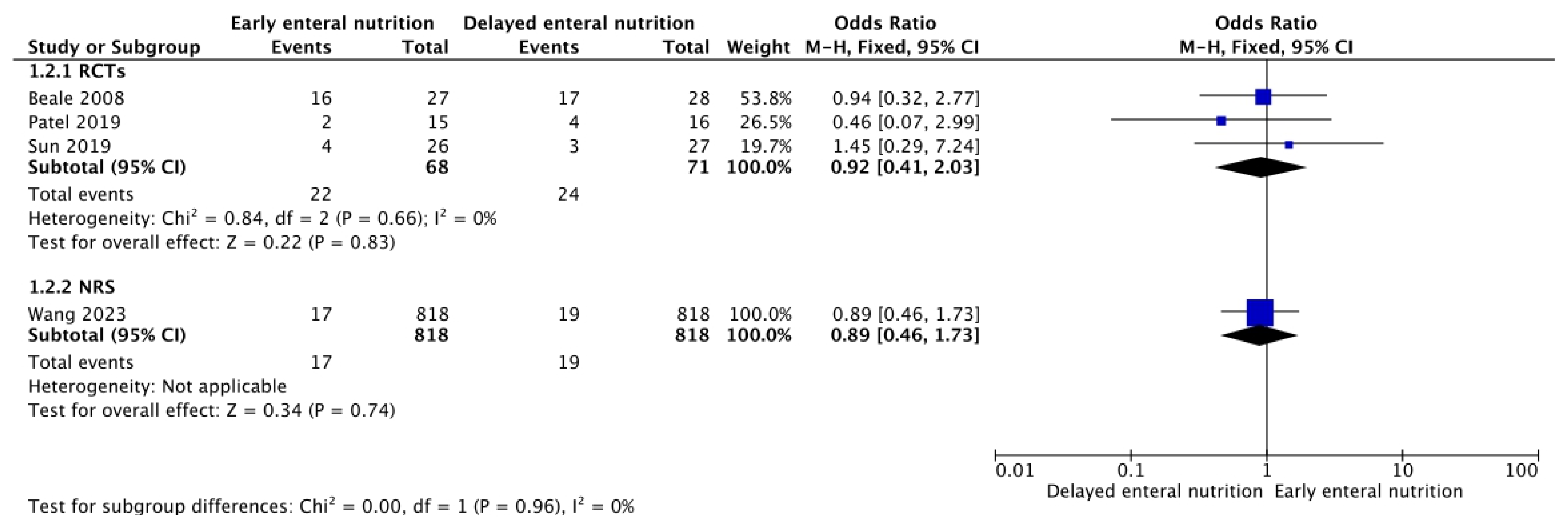

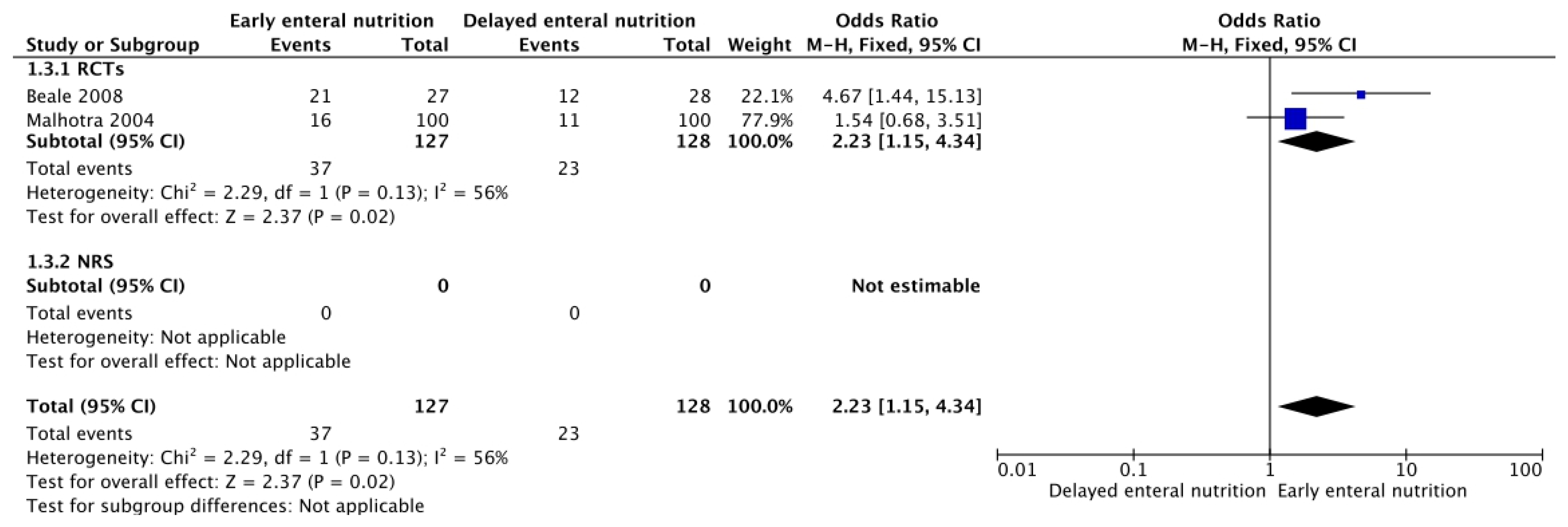

3.3. Adverse Events of Enteral Nutrition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Global Report on the Epidemiology and Burden of Sepsis: Current Evidence, Identifying Gaps and Future Directions; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/334216/9789240010789-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Estrada-Orozco, K.; Cantor-Cruz, F.; Larrotta-Castillo, D.; Díaz-Ríos, S.; Ruiz-Cardozo, M.A. Central venous catheter insertion and maintenance: Evidence-based clinical recommendations. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2020, 71, 115–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compher, C.; Bingham, A.L.; McCall, M.; Patel, J.; Rice, T.W.; Braunschweig, C.; McKeever, L. Guidelines for the provision of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2022, 46, 12–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugeles, S.-J.; Rueda, J.-D.; Díaz, C.-E.; Rosselli, D. Hyperproteic hypocaloric enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 17, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischmeyer, P.E. Tailoring nutrition therapy to illness and recovery. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barazzoni, R.; Deutz, N.E.P.; Biolo, G.; Bischoff, S.; Boirie, Y.; Cederholm, T.; Cuerda, C.; Delzenne, N.; Leon Sanz, M.; Ljungqvist, O.; et al. Carbohydrates and insulin resistance in clinical nutrition: Recommendations from the ESPEN expert group. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Han, X.; Qi, X.-Q.; Huang, C.-G.; Hou, L.-J. Nutritional Support for Patients Sustaining Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, O.; Ojo, O.O.; Feng, Q.; Boateng, J.; Wang, X.; Brooke, J.; Adegboye, A.R.A. The Effects of Enteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Doig, G.S.; Heighes, P.T.; Allingstrup, M.J. Early Enteral Nutrition Reduces Mortality and Improves Other Key Outcomes in Patients With Major Burn Injury: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 2036–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, X.; Kang, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, W.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Pei, L. Enteral nutrition provided within 48 hours after admission in severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo-Gonzalez, J.C.; Pichard, C.; Preiser, J.-C.; et al. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: Clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 1671–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elke, G.; Wang, M.; Weiler, N.; Day, A.G.; Heyland, D.K. Close to recommended caloric and protein intake by enteral nutrition is associated with better clinical outcome of critically ill septic patients: Secondary analysis of a large international nutrition database. Crit. Care 2014, 18, R29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuntrasakul, C.; Siltharm, S.; Chinswangwatanakul, V.; Pongprasobchai, T.; Chockvivatanavanit, S.; Bunnak, A. Early nutritional support in severe traumatic patients. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 1996, 79, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khalid, I.; Doshi, P.; DiGiovine, B. Early enteral nutrition and outcomes of critically ill patients treated with vasopressors and mechanical ventilation. Am. J. Crit. Care 2010, 19, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Tugwell, P.; Reeves, B.C.; Akl, E.A.; Santesso, N.; Spencer, F.A.; Shea, B.; Wells, G.; Helfand, M. Non-randomized studies as a source of complementary, sequential or replacement evidence for randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res. Synth Methods 2013, 4, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo-Ardila, C.F.; Paez-Castellanos, E.; Bolaños-Palacios, J.C.; Bautista-Charry, A.A. Spatulas for operative vaginal birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 156, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool; McMaster University and Evidence Prime: Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2023; Available online: http://gradepro.org (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Hultcrantz, M.; Rind, D.; Akl, E.A.; Treweek, S.; Mustafa, R.A.; Iorio, A.; Alper, B.S.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Murad, M.H.; Ansari, M.T.; et al. The GRADE Working Group clarifies the construct of certainty of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 87, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schünemann, H.J. Interpreting GRADE’s levels of certainty or quality of the evidence: GRADE for statisticians, considering review information size or less emphasis on imprecision? J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beale, R.J.; Sherry, T.; Lei, K.; Campbell-Stephen, L.; McCook, J.; Smith, J.; Venetz, W.; Alteheld, B.; Stehle, P.; Schneider, H. Early enteral supplementation with key pharmaconutrients improves Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score in critically ill patients with sepsis: Outcome of a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, N.; Gupta, M.K.; Minocha, V.R. Early Enteral Feeding by Nasoenteric Tubes in Patients with Perforation Peritonitis. World J. Surg. 2005, 29, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, A.; Mathur, A.K.; Gupta, S. Early enteral nutrition after surgical treatment of gut perforations: A prospective randomised study. J. Postgrad. Med. 2004, 50, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.J.; Kozeniecki, M.; Peppard, W.J.; Peppard, S.R.; Zellner-Jones, S.; Graf, J.; Szabo, A.; Heyland, D.K. Phase 3 Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Early Trophic Enteral Nutrition With “No Enteral Nutrition” in Mechanically Ventilated Patients With Septic Shock. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.-K.; Zhang, W.-H.; Chen, W.-X.; Wang, X.; Mu, X.-W. Effects of early enteral nutrition on Th17/Treg cells and IL-23/IL-17 in septic patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2799–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haac, B.; Henry, S.; Diaz, J.; Scalea, T.; Stein, D. Early Enteral Nutrition is Associated with Reduced Morbidity in Critically Ill Soft Tissue Patients. Am. Surg. 2018, 84, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhang, S.; Cai, M.; Chu, X.; Zheng, D.; Lou, M.; Cui, K.; Zhang, M.; Sun, R.; et al. Effects of early enteral nutrition on the prognosis of patients with sepsis: Secondary analysis of acute gastrointestinal injury study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 3793–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, Y.; Fujita, M.; Yagi, T.; Todani, M.; Nakahara, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Kaneda, K.; Oda, Y.; Tsuruta, R. Early enteral nutrition is associated with reduced in-hospital mortality from sepsis in patients with sarcopenia. J. Crit. Care 2018, 47, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Chen, W.; Shen, X.; Fu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H. Effects of Early Enteral Nutrition on Immune Function and Prognosis of Patients With Sepsis on Mechanical Ventilation. J. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 35, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ángeles Márquez, M.; Aisa Álvarez, A.; Aguirre Sánchez, J.S.; Martínez Díaz, B.A.; Montaño Jiménez, A. Cohort study to evaluate the association between the time of initiation of nutrition with days of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with septic shock. Med. Crítica 2023, 37, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Reyes, L.; Patel, J.J.; Jiang, X.; Yataco, A.C.; Day, A.G.; Shah, F.; Zelten, J.; Tamae-Kakazu, M.; Rice, T.; Heyland, D.K. Early versus delayed enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients with circulatory shock: A nested cohort analysis of an international multicenter, pragmatic clinical trial. Crit. Care 2022, 26, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, J.J.; Kozeniecki, M.; Biesboer, A.; Peppard, W.; Ray, A.S.; Thomas, S.; Jacobs, E.R.; Nanchal, R.; Kumar, G. Early Trophic Enteral Nutrition Is Associated with Improved Outcomes in Mechanically Ventilated Patients with Septic Shock: A Retrospective Review. J. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 31, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slone, S.D. Effect of Enteral Feeding Timing in Septic Shock Patients. DNP Projects 98. 2016. Available online: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/dnp_etds/98 (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- Sun, J.-K.; Yuan, S.-T.; Mu, X.-W.; Zhang, W.-H.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.; Wang, X.; Zheng, S.-Y. Effects of early enteral nutrition on T helper lymphocytes of surgical septic patients. Medicine 2017, 96, e7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Ding, S.; He, S.-Y.; Liu, S.-B.; Lu, Z.-J.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Hou, L.-W.; Wang, B.-S.; Zhang, J.-B. Early Enteral Nutrition and Sepsis-Associated Acute Kidney Injury: A Propensity Score Matched Cohort Study Based on the MIMIC-III Database. Yonsei Med. J. 2023, 64, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, R.C.A.; Mendoza, A.J.C.; Ballesteros Díaz, H. Nutritional evaluation in gynecological surgery. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 1989, 40, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; de Plata, A.A.; Mosquera-Escudero, M.; Ortega, J.G.; Salazar, B.; Echeverri, I.; Saldarriaga-Gil, W. The effect of aerobic exercise on oxygen consumption in healthy females: A randomized clinical trial. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2011, 62, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Barriga, A.P.; Perdomo, O. Medición del consumo de oxígeno del miocardio en el puerperio normal: Ejemplo de eficiencia fisiológica. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Ginecol. 2005, 56, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Suárez, J.A.; González, M.V.; Monsalve, G.; Escobar-Vidarte, M.F.; Vasco-Ramírez, M. Colombian consensus for the definition of admission criteria to intensive care units in critically ill pregnant patients. Rev. Colomb. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 65, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.J.; Ko, R.-E.; Park, C.-M.; Suh, G.Y.; Hwang, J.; Chung, C.R. The Effectiveness of Early Enteral Nutrition on Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Sepsis Patients: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grillo-Ardila, C.F.; Tibavizco-Palacios, D.; Triana, L.C.; Rugeles, S.J.; Vallejo-Ortega, M.T.; Calderón-Franco, C.H.; Ramírez-Mosquera, J.J. Early Enteral Nutrition (within 48 h) for Patients with Sepsis or Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111560

Grillo-Ardila CF, Tibavizco-Palacios D, Triana LC, Rugeles SJ, Vallejo-Ortega MT, Calderón-Franco CH, Ramírez-Mosquera JJ. Early Enteral Nutrition (within 48 h) for Patients with Sepsis or Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2024; 16(11):1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111560

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrillo-Ardila, Carlos F., Diego Tibavizco-Palacios, Luis C. Triana, Saúl J. Rugeles, María T. Vallejo-Ortega, Carlos H. Calderón-Franco, and Juan J. Ramírez-Mosquera. 2024. "Early Enteral Nutrition (within 48 h) for Patients with Sepsis or Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 16, no. 11: 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111560

APA StyleGrillo-Ardila, C. F., Tibavizco-Palacios, D., Triana, L. C., Rugeles, S. J., Vallejo-Ortega, M. T., Calderón-Franco, C. H., & Ramírez-Mosquera, J. J. (2024). Early Enteral Nutrition (within 48 h) for Patients with Sepsis or Septic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 16(11), 1560. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111560