Long Follow-Up Times Weaken Observational Diet–Cancer Study Outcomes: Evidence from Studies of Meat and Cancer Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Data Used in This Article

3.2. Recall Bias

3.3. How Red Meat and Processed Meat Increase Cancer Risk

3.4. Ecological Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- In terms of new observational studies of diet and risk of disease, dietary intake should be assessed within 4 years before diagnosis, with shorter times preferred. Earlier times of diet assessment appear less likely to reveal associations but may also be included when available.

- CC or NCC studies should be preferred over cohort studies whenever possible, reducing time and effort needed for collecting data and conserving biological specimens.

- Observational studies with short follow-up times or intervals between disease diagnosis and dietary data should be given equal or higher standing than those with longer times in assessing diet’s role in risk of disease.

- Previous meta-analyses of both CC and cohort studies of dietary intake and disease outcomes should be revised when possible, with appropriate adjustments for interval or duration of follow-up.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mc Cullough, M.; Giovannucci, E. Nutritional Epidemiology. In Nutritional Epidemiology, 2nd ed.; Heber, D., Blackburn, G.L., Go, V.L.W., Milner, J., Eds.; Academic Press, Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.B. Effect of interval between serum draw and follow-up period on relative risk of cancer incidence with respect to 25-hydroxyvitamin D level: Implications for meta-analyses and setting vitamin D guidelines. Dermatoendocrinology 2011, 3, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and colorectal adenomas: Case-control versus nested case-control studies. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, A.; Grant, W.B. Vitamin D and Cancer: An Historical Overview of the Epidemiology and Mechanisms. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B. Effect of follow-up time on the relation between prediagnostic serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and all-cause mortality rate. Dermatoendocrinology 2012, 4, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorde, R.; Sneve, M.; Hutchinson, M.; Emaus, N.; Figenschau, Y.; Grimnes, G. Tracking of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels during 14 years in a population-based study and during 12 months in an intervention study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 171, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

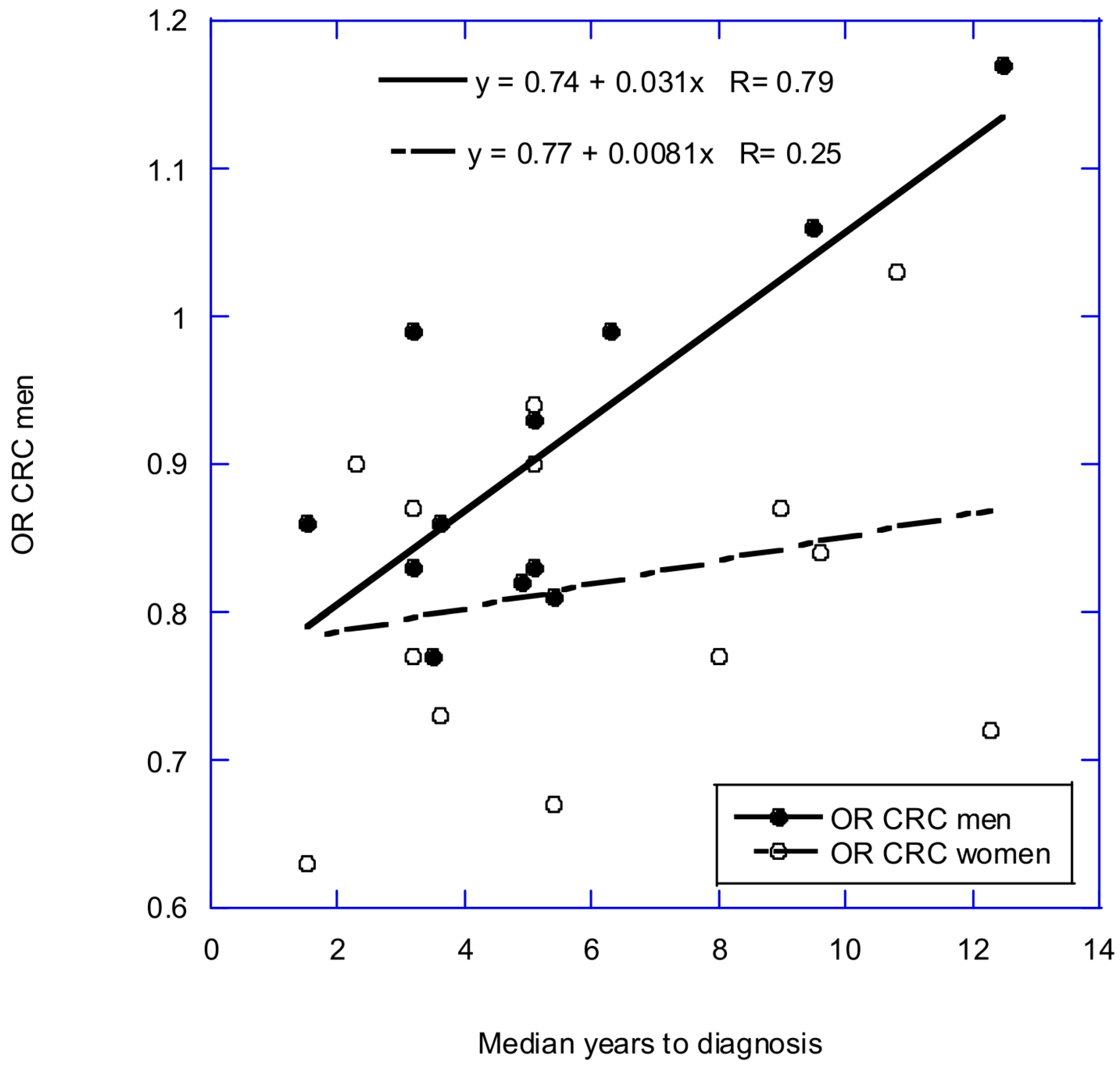

- McCullough, M.L.; Zoltick, E.S.; Weinstein, S.J.; Fedirko, V.; Wang, M.; Cook, N.R.; Eliassen, A.H.; Zeleniuch-Jacquotte, A.; Agnoli, C.; Albanes, D.; et al. Circulating Vitamin D and Colorectal Cancer Risk: An International Pooling Project of 17 Cohorts. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adult Obesity Facts. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Sans, P.; Combris, P. World meat consumption patterns: An overview of the last fifty years (1961–2011). Meat Sci. 2015, 109, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Song, M.; Eliassen, A.H.; Wang, M.; Fung, T.T.; Clinton, S.K.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Tabung, F.K.; et al. Optimal dietary patterns for prevention of chronic disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.A.; Kwon, S.O.; Lee, J.K.; Keum, N.; Park, S.M. Effect of Red, Processed, and White Meat Consumption on the Risk of Gastric Cancer: An Overall and Dose(-)Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Mante Angua, K.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 937–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norat, T.; Lukanova, A.; Ferrari, P.; Riboli, E. Meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: Dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 98, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaianzadeh, A.; Ghorbani, M.; Resaeian, S.; Kassani, A. Red Meat Consumption and Breast Cancer Risk in Premenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Middle East J. Cancer 2018, 9, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; An, S.; Hou, L.; Chen, P.; Lei, C.; Tan, W. Red and processed meat intake and risk of bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 2100–2110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crippa, A.; Larsson, S.C.; Discacciati, A.; Wolk, A.; Orsini, N. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of bladder cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, N.D.; Willett, W.C.; Ding, E.L. The Misuse of Meta-analysis in Nutrition Research. JAMA 2017, 318, 1435–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison-Loschmann, L.; Sporle, A.; Corbin, M.; Cheng, S.; Harawira, P.; Gray, M.; Whaanga, T.; Guilford, P.; Koea, J.; Pearce, N. Risk of stomach cancer in Aotearoa/New Zealand: A Maori population based case-control study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, M.H.; Sinha, R.; Heineman, E.F.; Rothman, N.; Markin, R.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Correa, P.; Zahm, S.H. Risk of adenocarcinoma of the stomach and esophagus with meat cooking method and doneness preference. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 71, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.T.; Chow, W.H.; Yang, G.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O.; Jin, F.; Gao, R.N.; Gao, Y.T.; Fraumeni, J.F., Jr. Dietary habits and stomach cancer in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Cancer 1998, 76, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Gallus, S.; Lagiou, P.; Trichopoulos, D.; Levi, F.; Negri, E. Red meat intake and cancer risk: A study in Italy. Int. J. Cancer 2000, 86, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissowska, J.; Gail, M.H.; Pee, D.; Groves, F.D.; Sobin, L.H.; Nasierowska-Guttmejer, A.; Sygnowska, E.; Zatonski, W.; Blot, W.J.; Chow, W.H. Diet and stomach cancer risk in Warsaw, Poland. Nutr. Cancer 2004, 48, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; La Vecchia, C.; DesMeules, M.; Negri, E.; Mery, L.; Canadian Cancer Registries Epidemiology Research, G. Meat and fish consumption and cancer in Canada. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourfarzi, F.; Whelan, A.; Kaldor, J.; Malekzadeh, R. The role of diet and other environmental factors in the causation of gastric cancer in Iran—A population based study. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 1953–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; De Stefani, E.; Ronco, A.; Boffetta, P.; Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Acosta, G.; Mendilaharsu, M. Meat consumption and cancer risk: A case-control study in Uruguay. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2009, 10, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Ronco, A.; Boffetta, P.; Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Barrios, E.; Acosta, G.; Mendilaharsu, M.; De Stefani, E. Meat consumption and cancer risk: A multisite casecontrol study in Uruguay. Cancer Therapy 2009, 7, 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maso, M.; Talamini, R.; Bosetti, C.; Montella, M.; Zucchetto, A.; Libra, M.; Negri, E.; Levi, F.; La Vecchia, C.; Franceschi, S.; et al. Red meat and cancer risk in a network of case-control studies focusing on cooking practices. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 3107–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epplein, M.; Zheng, W.; Li, H.; Peek, R.M., Jr.; Correa, P.; Gao, J.; Michel, A.; Pawlita, M.; Cai, Q.; Xiang, Y.B.; et al. Diet, Helicobacter pylori strain-specific infection, and gastric cancer risk among Chinese men. Nutr. Cancer 2014, 66, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Closas, R.; Garcia-Closas, M.; Kogevinas, M.; Malats, N.; Silverman, D.; Serra, C.; Tardon, A.; Carrato, A.; Castano-Vinyals, G.; Dosemeci, M.; et al. Food, nutrient and heterocyclic amine intake and the risk of bladder cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2007, 43, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Forman, M.R.; Wang, J.; Grossman, H.B.; Chen, M.; Dinney, C.P.; Hawk, E.T.; Wu, X. Intake of red meat and heterocyclic amines, metabolic pathway genes and bladder cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 1892–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.W.; Cross, A.J.; Baris, D.; Ward, M.H.; Karagas, M.R.; Johnson, A.; Schwenn, M.; Cherala, S.; Colt, J.S.; Cantor, K.P.; et al. Dietary intake of meat, fruits, vegetables, and selective micronutrients and risk of bladder cancer in the New England region of the United States. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, F.; Xie, L.P.; Hu, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Hemelt, M.; Reulen, R.C.; Wong, Y.C.; Tam, P.C.; Yang, K.; Chai, C.; et al. Dietary consumption and diet diversity and risk of developing bladder cancer: Results from the South and East China case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, K.B. The role of nutrition in cancer development and prevention. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 114, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, W.; Gustafson, D.R.; Sinha, R.; Cerhan, J.R.; Moore, D.; Hong, C.P.; Anderson, K.E.; Kushi, L.H.; Sellers, T.A.; Folsom, A.R. Well-done meat intake and the risk of breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toniolo, P.; Riboli, E.; Shore, R.E.; Pasternack, B.S. Consumption of meat, animal products, protein, and fat and risk of breast cancer: A prospective cohort study in New York. Epidemiology 1994, 5, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Hel, O.L.; Peeters, P.H.; Hein, D.W.; Doll, M.A.; Grobbee, D.E.; Ocke, M.; Bueno de Mesquita, H.B. GSTM1 null genotype, red meat consumption and breast cancer risk (The Netherlands). Cancer Causes Control 2004, 15, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertig, D.M.; Hankinson, S.E.; Hough, H.; Spiegelman, D.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C.; Kelsey, K.T.; Hunter, D.J. N-acetyl transferase 2 genotypes, meat intake and breast cancer risk. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothlings, U.; Yamamoto, J.F.; Wilkens, L.R.; Murphy, S.P.; Park, S.Y.; Henderson, B.E.; Kolonel, L.N.; Le Marchand, L. Meat and heterocyclic amine intake, smoking, NAT1 and NAT2 polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2098–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravi, F.; Decarli, A.; Russo, A.G. Risk factors for breast cancer in a cohort of mammographic screening program: A nested case-control study within the FRiCaM study. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Blake, S.N. Diet’s role in modifying risk of Alzheimer’s disease: History and present understanding. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 96, 1353–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.J.; Ferrucci, L.M.; Risch, A.; Graubard, B.I.; Ward, M.H.; Park, Y.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Schatzkin, A.; Sinha, R. A large prospective study of meat consumption and colorectal cancer risk: An investigation of potential mechanisms underlying this association. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2406–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.R. Meat and cancer. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, V.S.; Quek, S.Y. The relationship of red meat with cancer: Effects of thermal processing and related physiological mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1153–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascella, M.; Bimonte, S.; Barbieri, A.; Del Vecchio, V.; Caliendo, D.; Schiavone, V.; Fusco, R.; Granata, V.; Arra, C.; Cuomo, A. Dissecting the mechanisms and molecules underlying the potential carcinogenicity of red and processed meat in colorectal cancer (CRC): An overview on the current state of knowledge. Infect. Agent. Cancer 2018, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samraj, A.N.; Pearce, O.M.; Laubli, H.; Crittenden, A.N.; Bergfeld, A.K.; Banda, K.; Gregg, C.J.; Bingman, A.E.; Secrest, P.; Diaz, S.L.; et al. A red meat-derived glycan promotes inflammation and cancer progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, C.; Zhou, Y. Red meat and colon cancer: A review of mechanistic evidence for heme in the context of risk assessment methodology. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 131–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouhani, M.H.; Salehi-Abargouei, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Azadbakht, L. Is there a relationship between red or processed meat intake and obesity? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.M.Y.; Wellberg, E.A.; Kopp, J.L.; Johnson, J.D. Hyperinsulinemia in Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Diabetes Metab. J. 2021, 45, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer increasing among meat eaters. New York Times, 24 September 1907; p. 7.

- Leffingwell, A.C., III. Malignant tumors and their relation to our meat supply. In American Meat and Its Influence upon the Public Health; George Bell & Sons: London, UK, 1910; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, B.; Doll, R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int. J. Cancer 1975, 15, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UICC. Cancer Incidence in Seven Continents; Doll, R., Payne, P., Waternouse, J.A.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- UICC. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents; Doll, R., Muir, C., Waternouse, J.A.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1970; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ognjanovic, S.; Yamamoto, J.; Maskarinec, G.; Le Marchand, L. NAT2, meat consumption and colorectal cancer incidence: An ecological study among 27 countries. Cancer Causes Control 2006, 17, 1175–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, D.M.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Pisani, P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 94, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FoodBalanceSheets. FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 1 November 2006).

- Brockton, N.; Little, J.; Sharp, L.; Cotton, S.C. N-acetyltransferase polymorphisms and colorectal cancer: A HuGE review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 151, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Grant, W.B. Dietary Links to Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dis. Revier 1997, 2, 42–55. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.B. An estimate of premature cancer mortality in the U.S. due to inadequate doses of solar ultraviolet-B radiation. Cancer 2002, 94, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Garland, C.F. The association of solar ultraviolet B (UVB) with reducing risk of cancer: Multifactorial ecologic analysis of geographic variation in age-adjusted cancer mortality rates. Anticancer Res. 2006, 26, 2687–2699. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.B. The role of meat in the expression of rheumatoid arthritis. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bircher-Benner, M. The Prevention of Incurable Disease; James Clarke Company: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Broke, M.O. Unsere Nahrung, Unser Shicksal; EMU: Lanstein, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, V.S.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Global obesity: Trends, risk factors and policy implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, F.L.; Steur, M.; Allen, N.E.; Appleby, P.N.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans: Results from the EPIC-Oxford study. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Useros, J.; Garcia-Foncillas, J. Obesity and colorectal cancer: Molecular features of adipose tissue. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscoe, F.P.; Schymura, M.J. Solar ultraviolet-B exposure and cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1993–2002. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.; Yue, Y.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Y. Immunosenescence: A key player in cancer development. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, K.; Akutsu, T.; Ohdaira, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Urashima, M. Effect of Vitamin D Supplements on Relapse or Death in a p53-Immunoreactive Subgroup with Digestive Tract Cancer: Post Hoc Analysis of the AMATERASU Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2328886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratjen, I.; Enderle, J.; Burmeister, G.; Koch, M.; Nothlings, U.; Hampe, J.; Lieb, W. Post-diagnostic reliance on plant-compared with animal-based foods and all-cause mortality in omnivorous long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; Aragaki, A.K.; Anderson, G.L.; Pan, K.; Neuhouser, M.L.; Manson, J.E.; Thomson, C.A.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Lane, D.S.; Johnson, K.C.; et al. Dietary Modification and Breast Cancer Mortality: Long-Term Follow-Up of the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Espin, C.; Agudo, A. The Role of Diet in Prognosis among Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dietary Patterns and Diet Interventions. Nutrients 2022, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herforth, A.; Arimond, M.; Alvarez-Sanchez, C.; Coates, J.; Christianson, K.; Muehlhoff, E. A Global Review of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockstrom, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlee, L.; Gomez-Donoso, C.; Acton, R.B.; Goodman, S.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Penney, T.; Roberto, C.A.; Sacks, G.; White, M.; Hammond, D. Meat-Reduced Dietary Practices and Efforts in 5 Countries: Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys in 2018 and 2019. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 57S–66S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Cofnas, N. Should dietary guidelines recommend low red meat intake? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2763–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Smith, N.W.; Adesogan, A.T.; Beal, T.; Iannotti, L.; Moughan, P.J.; Mann, N. The role of meat in the human diet: Evolutionary aspects and nutritional value. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.C.; Zeraatkar, D.; Han, M.A.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; Valli, C.; El Dib, R.; Marshall, C.; Stover, P.J.; Fairweather-Taitt, S.; Wojcik, G.; et al. Unprocessed Red Meat and Processed Meat Consumption: Dietary Guideline Recommendations From the Nutritional Recommendations (NutriRECS) Consortium. Ann. Intern Med. 2019, 171, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.; De Smet, S.; Leroy, F.; Mente, A.; Stanton, A. Non-communicable disease risk associated with red and processed meat consumption-magnitude, certainty, and contextuality of risk? Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Meat | Comparison | N | Yrs | RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC, pop | Red | High vs. low | 12 | 1997–2014 | 1.42 (1.12–1.82) | [11] |

| CC, hosp | Red | High vs. low | 8 | 1997–2012 | 1.81 (1.41–2.33) | |

| CC | Red | Per 100 g/day | 14 | 1997–2017 | 1.31 (1.13–1.42) | |

| CC, pop | Processed | High vs. low | 11 | 1990–2012 | 1.58 (1.32–1.89) | |

| CC, hosp | Processed | High vs. low | 12 | 1997–2012 | 2.03 1.56–2.68) | |

| CC | Processed | Per 50 g/day | 12 | 1990–2014 | 2.17 (1.51–3.11) | |

| CC, pop | White | High vs. low | 9 | 1998–2013 | 0.75 (0.61–0.93) | |

| CC, hosp | White | High vs. low | 8 | 2001–2011 | 0.81 (0.61–1.06) | |

| CC | White | Per 100 g/day | 10 | 1998–2011 | 0.65 (0.35–1.25) | |

| Cohort | Red | High vs. low | 6 | 2005–2020 | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | [12] |

| Cohort | Processed | High vs. low | 10 | 1990–2020 | 1.15 (0.96–1.37) |

| Study | Meat | Comparison | N | Yrs | RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | Red | High vs. low | 14 | 1984–1999 | 1.36 (1.17–1.59) | [13] |

| CC | Processed | High vs. low | 16 | 1973–1999 | 1.29 (1.09–1.52) | |

| Cohort | Red | High vs. low | 22 | 1997–2020 | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | [12] |

| Cohort | Processed | High vs. low | 23 | 1997–2020 | 1.18 (1.13–1.24) |

| Study | Meat | Comparison | N | Yrs | RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | Red | High vs. low | 9 | 1991–2015 | 1.55 (1.26–1.91) | [14] |

| Cohort | Total red | High vs. low | 16 | 1989–2020 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15) | [12] |

| Cohort | Processed | High vs. low | 16 | 1999–2020 | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) |

| Study | Meat | Comparison | N | Yrs | RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | Red | High vs. low | 9 | 1991–2012 | 1.23 (0.91–1.67) | [15] |

| CC | Processed | High vs. low | 6 | 1991–2012 | 1.46 (1.10–1.95) | |

| CC | Red | Per 100 g/day | 7 | 2000–2011 | 1.94 (1.16–3.24) | [16] |

| CC | Processed | Per 50 g/day | 6 | 2007–2014 | 1.31 (1.06–1.63) | |

| Cohort | Red | High vs. low | 5 | 2000–2011 | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) | [15] |

| Cohort | Processed | High vs. low | 5 | 2000–2011 | 1.08 (0.96–1.20) | |

| Cohort | Red | Per 100 g/day | 6 | 2000–2013 | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | [16] |

| Cohort | Processed | Per 50 g/day | 5 | 2000–2010 | 1.10 (0.95–1.27) |

| N | Yr Published | Yrs before Dietary Data | RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 154 | 1997 | 1 | 1.28 (1.08–1.52) | [19] |

| 770 M | 1998 | 10 | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | [20] |

| 354 F | 1998 | 10 | 0.87 (0.70–1.09) | [20] |

| 745 | 2000 | 2 | 1.45 (1.22–1.71) | [21] |

| 274 | 2004 | 6 | 1.13 (0.95–1.35) | [22] |

| 1180 | 2008 | 2 | 1.19 (0.97–1.46) | [23] |

| 217 | 2009 | 1 | 2.64 (1.61–4.34) | [24] |

| 275 | 2009 | 1 | 1.27 (1.08–1.50) | [25] |

| 128 | 2009 | 1 | 1.76 (1.38–2.24) | [26] |

| 230 | 2013 | 2 | 1.31 (0.92–1.87) | [27] |

| 226 | 2014 | 3 | 1.50 (0.87–2.58) | [28] |

| N | Yr Published | Yrs before Dietary Data | RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 450 | 2000 | 2 | 2.13 (1.50–3.04) | [21] |

| 912 | 2007 | 5 | 0.84 (0.68–1.02) | [29] |

| 1029 | 2008 | 2 | 1.40 (1.10–1.77) | [23] |

| 254 | 2009 | 1 | 1.34 (1.07–1.69) | [25] |

| 884 | 2012 | 1 | 2.85 (1.79–4.55) | [30] |

| 1000 | 2012 | 5 | 1.23 (0.88–1.71) | [31] |

| 500 | 2012 | 1 | 1.94 (1.16–3.24) | [32] |

| Cancer | Population | Mean Follow-Up | Meat Type | Doneness, RR (95% CI) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | Iowa, USA Nc = 227; Nco = 603 | 2 years | Hamburger | R–M; 1.0 WD; 1.23 (0.89–1.71) VWD; 1.54 (0.96–2.47) p = 0.04 | [34] |

| Iowa, USA Nc = 249; Nco = 598 | 2 years | Beefsteak | R–M; 1.0 WD; 1.22 (0.89–1.71} VWD; 2.21 (1.30–3.77) p = 0.04 | ||

| Iowa, USA Nc = 260; Nco = 436 | 2 years | Bacon | R–M; 1.0 WD; 1.26 (0.71–2.22) VWD; 1.64 (0.92–2.91) p = 0.01 | ||

| g/day, RR (95% CI) | |||||

| Breast | New York Nc = 180; Nco = 180 | 3 years | Total meat | 8 g/day; 1.0 20; 1.11 (0.63–2.02) 30; 1.88 (1.10–3.21) 44; 1.62 (0.93–2.82) 73; 1.87 (1.09–3.21) p = 0.01 | [35] |

| Breast | The Netherlands Nc = 229; Nco = 263 | 3.8 years 22 ± 18 months * | Fresh red | <30: 1.00 30–44: 1.31 (0.83–2.05) >45: 1.30 (0.83–2.02) | [36] |

| Nc = 229; Nco = 262 | Processed | <20; 1.00 20–34; 0.95 (0.61–1.49) >35; 1.05 (0.67–1.64) | |||

| Breast | USA Nc = 455; Nco = 462 | 5 years | Red, incl. fresh and processed | ≤0.5 s/day; 1.0 0.51–1.0 s/day; 0.9 (0.7–1.3) >1.0 s/day; 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | [37] |

| USA Nc = 455; Nco = 462 | Processed | ≤0.14 s/day; 1.0 0.15–0.50 s/day; 1.3 (1.0–1.8) >0.50 s/day; 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | |||

| CRC | CA, HI, USA Nc = 1009; Nco = 1522 | 5 years | Red | <10.4 g/1000 kcal/day; 1.0 10.4–<17.7; 1.11 (0.80–1.28) 17.7–<26.0; 0.96 (0.74–1.23) p = 0.67 | [38] |

| Nc = 1009; Nco = 1522 | Processed | <3.54 g/1000 kcal/day; 1.0 3.5–<6.7; 1.04 (0.82–1.32) 6.7–<11.0; 1.13 (0.89–1.44) ≥11.0; 1.08 (0.8–1.39) p = 0.46 | |||

| Breast | Milan, Italy Nc = 3156; Nco = 9413 | 10 years | Red | <1 s/wk; 1.00 1 s/wk; 1.01 (0.90–1.12) 2–3 s/wk; 0.97 (0.87–1.08) ≥4 s/wk; 1.12 (0.96–1.31) p = 0.58 | [39] |

| Milan, Italy Nc = 3165; Nco = 9503 | 10 years | White | <1/wk; 1.00 1/wk; 1.06 (0.93–1.22) 2–3/wk; 1.14 (1.00–1.30) ≥4/wk; 1.09 (0.92–1.28) p = 0.11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grant, W.B. Long Follow-Up Times Weaken Observational Diet–Cancer Study Outcomes: Evidence from Studies of Meat and Cancer Risk. Nutrients 2024, 16, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010026

Grant WB. Long Follow-Up Times Weaken Observational Diet–Cancer Study Outcomes: Evidence from Studies of Meat and Cancer Risk. Nutrients. 2024; 16(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrant, William B. 2024. "Long Follow-Up Times Weaken Observational Diet–Cancer Study Outcomes: Evidence from Studies of Meat and Cancer Risk" Nutrients 16, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010026

APA StyleGrant, W. B. (2024). Long Follow-Up Times Weaken Observational Diet–Cancer Study Outcomes: Evidence from Studies of Meat and Cancer Risk. Nutrients, 16(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010026