What Differentiates Rural and Urban Patients with Type 1 Diabetes—A Pilot Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

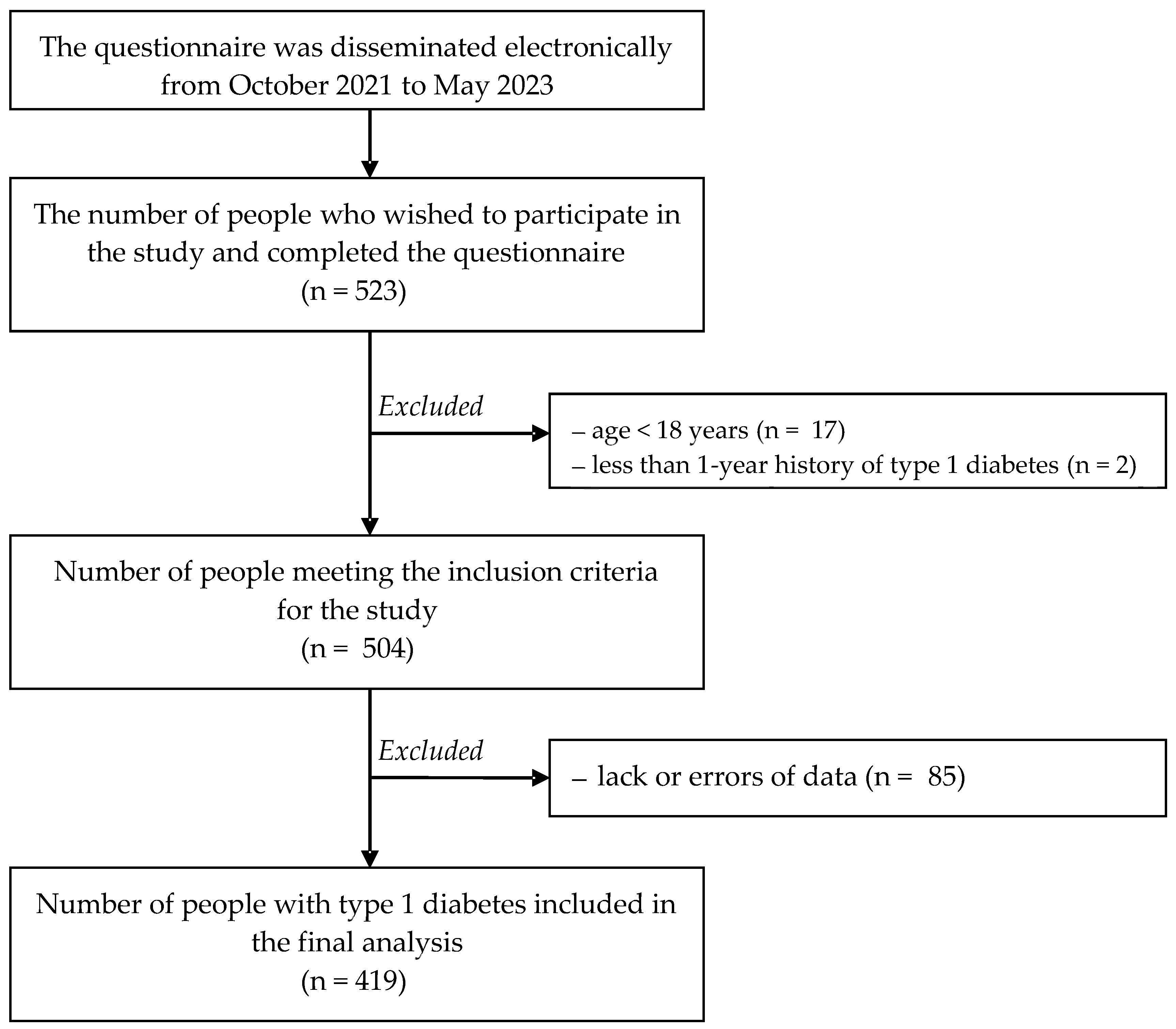

2.1. Participants and Study Design

- −

- The Diabetes Dietary Guidelines Adherence Index (DDGA Index), which includes up-to-date recommendations on healthy eating and behavioral therapy guidelines issued by the Polish Diabetes Association. The index is used to assess the frequency of the consumption of 29 groups of products and meal regularity. The value of the DDGA index is expressed as the sum of the points obtained (0–30 points, where 0 points is non-compliance with the recommendations, and 1 point is compliance with the recommendations regarding the frequency of the consumption of a specific product group). Higher values of the DDGA Index are associated with a higher degree of adherence to dietary recommendations [20].

- −

- The Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) questionnaire, based on Jurczyński’s adaptation, is composed of 8 statements that refer to the consequences of poor health status regarding the acceptance of limitations associated with the disease, no self-sufficiency, a sense of being dependent on others and a reduced sense of self-esteem. Each response is given a point value (strongly agree—1, strongly disagree—5). Scoring the lowest number of points (1) means a low level of adaptation to the disease, whereas strong disagreement (5 points) translates to disease acceptance. The total of 8–40 is a general outcome referring to the level of disease acceptance. With increasing acceptance, the degree of adaptation increases, and the sense of psychological discomfort decreases [21].

- −

- The Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised scale (DEPS-R) is a tool used to screen for eating disorders. The DEPS-R is diabetes-specific and is composed of 16 items. Respondents may select one of 6 responses on a 6-point Likert scale for each item. The total DEPS-R score ranges from 0 to 80 points. Higher overall DEPS-R scores indicate a higher likelihood of developing an eating disorder. According to the original version of the DEPS-R, a total score of 20 or above is assumed to be a threshold indicating a greater degree of disturbances [22].

- −

- The short version of the Eating Attitude Test EAT-26 is a standardized nutritional attitude test used as a screening tool to assess the risk of eating disorders. Individuals who score 20 or more points in the test are more likely to develop an eating disorder [23].

- −

- The Sense of Responsibility for Health Scale (SRHS), developed by Adamus [24], is composed of 14 items rated on a 5-point scale (1—hardly ever, 2—rarely, 3—sometimes, 4—often, 5—nearly always/very often). Only the total degree of responsibility for one’s health was subjected to evaluation in the present study. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was found to equal 0.724.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Florek-Łuszczki, M.; Choina, P.; Kostrzewa-Zabłocka, E.; Panasiuk, L.; Dziemidok, P. Medical and socio-demographic determinants of depressive disorders in diabetic patients. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grudziąż-Sękowska, J.; Sękowski, K.B.; Pinkas, J.; Jankowski, M. Blood glucose level testing in Poland—Do socio-economic factors influence its frequency? A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2023, 30, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akil, A.A.; Yassin, E.; Al-Maraghi, A.; Aliyev, E.; Al-Malki, K.; Fakhro, K.A. Diagnosis and treatment of type 1 diabetes at the dawn of the personalized medicine era. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primavera, M.; Giannini, C.; Chiarelli, F. Prediction and Prevention of Type 1 Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.L.; Mittal, R.; Bhalla, A.; Kumar, A.; Madan, H.; Pandhi, K.; Garg, Y.; Singh, K.; Jain, A.; Rana, S. Knowledge and Awareness About Diabetes Mellitus Among Urban and Rural Population Attending a Tertiary Care Hospital in Haryana. Cureus 2023, 15, e38359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworski, M.; Adamus, M.M. Health suggestibility, optimism and sense of responsibility for health in diabetic patients. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2016, 36, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. Diabetes self-management education: A review of published studies. Prim. Care Diabetes 2008, 2, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araszkiewicz, A.; Bandurska-Stankiewicz, E.; Borys, S.; Budzyński, A.; Cyganek, K.; Cypryk, K.; Czech, A.; Czupryniak, L.; Drzewoski, J.; Dzida, G. Zalecenia kliniczne dotyczące postępowania u osób z cukrzycą 2023. Stanowisko Polskiego Towarzystwa Diabetologicznego. Curr. Top. Diabetes 2023, 3, 1–136. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, N.A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V.R.; Bannuru, R.R.; Brown, F.M.; Bruemmer, D.; Collins, B.S.; Cusi, K.; Das, S.R.; Gibbons, C.H.; et al. Summary of revisions: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S5–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakarami, R.; Abdi, Z.; Ahmadnezhad, E.; Sheidaei, A.; Asadi-Lari, M. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of diabetes among Iranian population: Results of four national cross-sectional STEP wise approach to surveillance surveys. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, E.; Nowak-Kapusta, Z.; Dobrzyn-Matusiak, D.; Marcisz-Dyla, E.; Marcisz, C.; Krzemińska, S.A. An assessment of diabetes-dependent quality of life (ADDQoL) in women and men in Poland with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghassab-Abdollahi, N.; Nadrian, H.; Pishbin, K.; Shirzadi, S.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Saadati, F.; Moradi, M.S.; Azar, P.S.; Zhianfar, L. Gender and urban-rural residency based differences in the prevalence of type-2 diabetes mellitus and its determinants among adults in Naghadeh: Results of IraPEN survey. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, M.; Yamakawa, T.; Sakamoto, R.; Takahashi, K.; Suzuki, J.; Matsuura-Shinoda, M.; Shigematsu, E.; Tanaka, S.; Kaneshiro, M.; Asakura, T.; et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between quality of life and sleep quality in Japanese patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. J. 2022, 69, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, W.P.; Htet, A.S.; Bjertness, E.; Stigum, H.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Kjøllesdal, M.K.R. Urban-rural differences in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus among 25–74 year-old adults of the Yangon Region, Myanmar: Two cross-sectional studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, M.; Gebska-Kuczerowska, A.; Gorynski, P.; Wysocki, M.J. Analyses of hospitalization of diabetes mellitus patients in Poland by gender, age and place of residence. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2013, 20, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Song, J.; Lin, T.; Dixon, J.; Zhang, G.; Ye, H. Urbanization and health in China, thinking at the national, local and individual levels. Environ. Health 2016, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercado, C.I.; McKeever Bullard, K.; Gregg, E.W.; Ali, M.K.; Saydah, S.H.; Imperatore, G. Differences in U.S. Rural-Urban Trends in Diabetes ABCS, 1999–2018. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 1766–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.D.; Morello, C.M. Economic impact of and treatment options for type 2 diabetes. Am. J. Manag. Care 2017, 23, S231–S240. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, K.J.; Wen, H.; Joynt Maddox, K.E. Lack of access to specialists associated with mortality and preventable hospitalizations of rural Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1993–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sińska, B.I.; Dłużniak-Gołaska, K.; Jaworski, M.; Panczyk, M.; Duda-Zalewska, A.; Traczyk, I.; Religioni, U.; Kucharska, A. Undertaking Healthy Nutrition Behaviors by Patients with Type 1 Diabetes as an Important Element of Self-Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juczyński, Z. Narzędzia pomiaru w psychologii zdrowia. Przegląd Psychol. 1999, 42, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz, J.T.; Butler, D.A.; Volkening, L.K.; Antisdel, J.E.; Anderson, B.J.; Laffel, L.M. Brief screening tool for disordered eating in diabetes: Internal consistency and external validity in a contemporary sample of pediatric patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogoza, R.; Brytek-Matera, A.; Garner, D.M. Analysis of the EAT-26 in a non-clinical sample. Arch. Psych. Psych. 2016, 2, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamus, M.; Jaworski, M. A Sense of Responsibility for Health in Adolescents the Presentation of a new Research Tool. In Proceedings of the Conference material, European Health Psychology Research (EHPS), Innsbruck, Austria, 26–30 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.E.; Vasan, R.S. The southern rural health and mortality penalty: A review of regional health inequities in the United States. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 268, 113443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T. Association between perceived environmental pollution and health among urban and rural residents-a Chinese national study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljassim, N.; Ostini, R. Health literacy in rural and urban populations: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Orom, H.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kiviniemi, M.T. Differences in Rural and Urban Health Information Access and Use. J. Rural. Health 2019, 35, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobo, O.; Van Spall, H.G.C.; Mamas, M.A. Urban-rural disparities in diabetes-related mortality in the USA 1999–2019. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 2078–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlexander, T.P.; Malla, G.; Uddin, J.; Lee, D.C.; Schwartz, B.S.; Rolka, D.B.; Siegel, K.R.; Kanchi, R.; Pollak, J.; Andes, L.; et al. Urban and rural differences in new onset type 2 diabetes: Comparisons across national and regional samples in the diabetes LEAD network. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 19, 101161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugani, S.B.; Wood-Wentz, C.M.; Mielke, M.M.; Bailey, K.R.; Vella, A. Assessment of Disparities in Diabetes Mortality in Adults in US Rural vs Nonrural Counties, 1999–2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2232318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantyley, V. Health inequalities among rural and urban population of Eastern Poland in the context of sustainable development. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2017, 24, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolin, J.N.; Bellamy, G.R.; Ferdinand, A.O.; Vuong, A.M.; Kash, B.A.; Schulze, A.; Helduser, J.W. Rural Healthy People 2020: New Decade, Same Challenges. J. Rural. Health 2015, 31, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugani, S.B.; Mielke, M.M.; Vella, A. Burden and management of type 2 diabetes in rural United States. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2021, 37, e3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferdinand, A.O.; Akinlotan, M.A.; Callaghan, T.; Towne, S.D., Jr.; Bolin, J. Diabetes-related hospital mortality in the U.S.: A pooled cross-sectional study of the National Inpatient Sample. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2019, 33, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutledge, S.A.; Masalovich, S.; Blacher, R.J.; Saunders, M.M. Diabetes self-management education programs in nonmetropolitan counties—United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2017, 66, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, A.; Gothard, M.D.; Early, K.B. Glycemic outcomes among rural patients in the type 1 diabetes T1D Exchange registry, January 2016-March 2018: A cross-sectional cohort study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e002564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtyniak, B.; Goryński, P. Health Status of Polish Population and Its Determinants; NIPH: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020; pp. 486–508. [Google Scholar]

- Sytuacja Zdrowotna Ludności—OKŁADKA 2020 2. Available online: https://www.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Raport_ang_OK.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Jung, H.N.; Kim, S.; Jung, C.H.; Cho, Y.K. Association between Body Mass Index and Mortality in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 32, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edqvist, J.; Rawshani, A.; Adiels, M.; Björck, L.; Lind, M.; Svensson, A.M.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Sattar, N.; Rosengren, A. BMI, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 1 Diabetes: Findings Against an Obesity Paradox. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlström, E.H.; Sandholm, N.; Forsblom, C.M.; Thorn, L.M.; Jansson, F.J.; Harjutsalo, V.; Groop, P.H. Body Mass Index and Mortality in Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 5195–5204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, T.; Liu, J.; Probst, J.C.; Martin, A.B. The metabolic syndrome: Are rural residents at increased risk? J. Rural. Health 2013, 29, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Befort, C.A.; Nazir, N.; Perri, M.G. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: Findings from NHANES (2005–2008). J. Rural. Health 2012, 28, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbull, F.; Neal, B.; Algert, C.; Chalmers, J.; Chapman, N.; Cutler, J.; Woodward, M.; MacMahon, S.; Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Effects of different blood pressure-lowering regimens on major cardiovascular events in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus: Results of prospectively designed overviews of randomized trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.H.; Ooi, L.; Lai, Y.K. Telemedicine for the management of glycemic control and clinical outcomes of type 1 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Crabb, S.; Turnbull, D.; Oxlad, M. Barriers and facilitators to effective type 2 diabetes management in a rural context: A qualitative study with diabetic patients and health professionals. J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeed-Ariss, R.; Jackson, C.; Knapp, P.; Cheater, F.M. A systematic review of research into black and ethnic minority patients’ views on self-management of type 2 diabetes. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stumetz, K.S.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Mitrovich, C.; Early, K.B. Quality of care in rural youth with type 1 diabetes: A cross-sectional pilot assessment. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care. 2016, 4, e000300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlhenny, C.V.; Guzic, B.L.; Knee, D.R.; Wendekier, C.M.; Demuth, B.R.; Roberts, J.B. Using technology to deliver healthcare education to rural patients. Rural. Remote Health 2011, 11, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalewska, B.; Cybulski, M.; Jankowiak, B.; Krajewska-Kułak, E. Acceptance of Illness, Satisfaction with Life, Sense of Stigmatization, and Quality of Life among People with Psoriasis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 10, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, B.; Cummings, S.M.; Levine, R.S. The influence of religiosity on depression among low-income people with diabetes. Health Soc. Work 2009, 34, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuniarti, K.W.; Dewi, C.; Ningrum, R.P.; Widiastuti, M.; Asril, N.M. Illness perception, stress, religiosity, depression, social support, and self management of diabetes in Indonesia. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2013, 2, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrzyńska, K.; Szadkowska, A. Transition of young adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus from a pediatric to adult diabetes clinic—Problems, challenges and recommendations. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2014, 21, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Total (n = 419) | Urban Area (n = 321) | Rural Area (n = 98) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—M (SD) [years] | 33.1 (10.7) | 33.9 (11.3) | 30.7 (7.9) | 0.043 |

| Sex—n (%) | ||||

| Woman | 232 (55.4) | 177 (55.1) | 55 (56.1) | 0.864 |

| Man | 187 (44.6) | 144 (44.9) | 43 (43.9) | |

| Education—n (%) | ||||

| Primary/vocational | 37 (8.8) | 27 (6.4) | 10 (10.2) | 0.006 |

| Secondary | 174 (41.5) | 121 (37.7) | 53 (54.1) | |

| Tertiary | 208 (49.6) | 173 (53.9) | 35 (35.7) | |

| Variables | Total (n = 419) | Urban Area (n = 321) | Rural Area (n = 98) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI category—n (%) | ||||

| Underweight | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (2.0) | 0.014 |

| Healthy Weight | 216 (51.6) | 179 (55.8) | 37 (37.8) | |

| Overweight | 192 (45.8) | 134 (41.7) | 58 (59.2) | |

| Obesity | 6 (1.4) | 5 (1.6) | 1 (1.0) | |

| Variables | Total (n = 419) | Urban Area (n = 321) | Rural Area (n = 98) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c [%] M (SD) | 7.5 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.7) | 7.8 (1.7) | 0.013 |

| Duration of diabetes—M (SD) [years] | 18.8 (9.1) | 19.2 (9.6) | 17.5 (7.1) | 0.396 |

| Type of insulin therapy—n (%) | ||||

| Pens | 226 (53.9) | 173 (53.9) | 53 (54.1) | 0.974 |

| Insulin pumps | 193 (46.1) | 148 (46.1) | 45 (45.9) | |

| Insulin units per kilogram of body weight per day—n (%) | ||||

| <0.4 | 112 (26.7) | 87 (27.1) | 25 (25.5) | 0.836 |

| 0.4–0.75 | 207 (49.4) | 156 (48.6) | 51 (52.0) | |

| >0.75 | 100 (23.9) | 78 (24.3) | 22 (22.4) | |

| Hypoglycemic episodes—n (%) | ||||

| Never | 70 (16.7) | 53 (16.5) | 17 (17.3) | 0.239 |

| 1–3 times a week | 206 (49.2) | 166 (51.7) | 40 (40.8) | |

| 4–6 times a week | 121 (28.9) | 87 (27.1) | 34 (34.7) | |

| Every day | 22 (5.3) | 15 (4.7) | 7 (7.1) | |

| Diabetes control based on hypoglycemic episodes—n (%) | ||||

| HbA1c ≤ 7% | 276 (65.9) | 219 (68.2) | 57 (58.2) | 0.066 |

| HbA1c > 7% | 143 (34.1) | 102 (31.8) | 41 (41.8) | |

| Hyperglycemic episodes—n (%) | ||||

| Never | 45 (10.7) | 34 (10.6) | 11 (11.2) | 0.921 |

| 1–3 times a week | 127 (30.3) | 100 (31.2) | 27 (27.6) | |

| 4–6 times a week | 171 (40.8) | 130 (40.5) | 41 (41.8) | |

| Every day | 76 (18.1) | 57 (17.8) | 19 (19.4) | |

| Number of glucose measurements daily—n (%) | ||||

| <5 | 103 (24.6) | 70 (21.8) | 33 (33.7) | 0.001 |

| 5–9 | 221 (52.7) | 185 (57.6) | 36 (36.7) | |

| 10 and more | 95 (22.7) | 66 (20.6) | 29 (29.6) | |

| Variables | Total (n = 419) | Urban Area (n = 321) | Rural Area (n = 98) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using psychological consultations—n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 94 (22.4) | 76 (23.7) | 18 (18.4) | 0.270 |

| No | 325 (77.6) | 245 (76.3) | 80 (81.6) | |

| Using psychiatric consultations—n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 66 (15.8) | 51 (15.9) | 15 (15.3) | 0.890 |

| No | 353 (84.2) | 270 (84.1) | 83 (84.7) | |

| Variables | Total (n = 419) | Urban Area (n = 321) | Rural Area (n = 98) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIS—M (SD) | 27.2 (8.2) | 26.6 (8.1) | 29.1 (8.2) | 0.006 |

| DDGA Index—M (SD) | 17.7 (4.2) | 18.0 (4.2) | 16.5 (3.9) | 0.001 |

| DEPS-R Scale—M (SD) | 16.7 (10.7) | 16.1 (9.8) | 18.7 (12.9) | 0.206 |

| EAT—M (SD) | 10.1 (8.0) | 10.0 (7.6) | 10.4 (9.1) | 0.810 |

| SRHS—M (SD) | 55.7 (7.7) | 56.3 (7.5) | 53.9 (8.1) | 0.018 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sińska, B.I.; Kucharska, A.; Rzońca, E.; Wronka, L.; Bączek, G.; Gałązkowski, R.; Olejniczak, D.; Rzońca, P. What Differentiates Rural and Urban Patients with Type 1 Diabetes—A Pilot Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010022

Sińska BI, Kucharska A, Rzońca E, Wronka L, Bączek G, Gałązkowski R, Olejniczak D, Rzońca P. What Differentiates Rural and Urban Patients with Type 1 Diabetes—A Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2024; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleSińska, Beata I., Alicja Kucharska, Ewa Rzońca, Leszek Wronka, Grażyna Bączek, Robert Gałązkowski, Dominik Olejniczak, and Patryk Rzońca. 2024. "What Differentiates Rural and Urban Patients with Type 1 Diabetes—A Pilot Study" Nutrients 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010022

APA StyleSińska, B. I., Kucharska, A., Rzońca, E., Wronka, L., Bączek, G., Gałązkowski, R., Olejniczak, D., & Rzońca, P. (2024). What Differentiates Rural and Urban Patients with Type 1 Diabetes—A Pilot Study. Nutrients, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16010022