Diet-Related Disparities and Childcare Food Environments for Vulnerable Children in South Korea: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

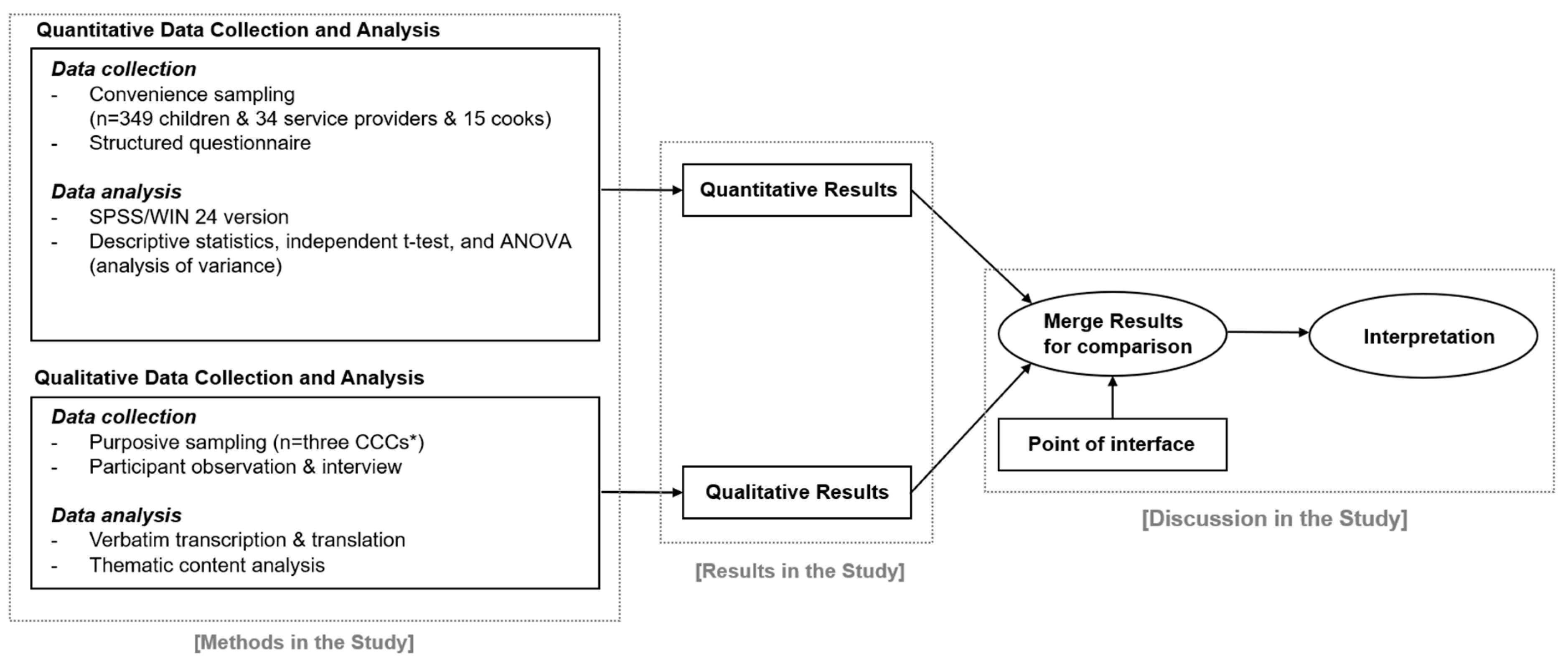

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Setting

2.2.1. Quantitative Phase

2.2.2. Qualitative Phase

2.3. Instrument

2.3.1. Quantitative Phase

- (1)

- Children’s eating behaviors: We used the Nutrition Quotient (NQ) [32] to investigate children’s eating behaviors. The NQ was developed by the Korean Nutrition Society, a leading organization in nutrition and health promotion in South Korea. Previous studies using large-scale samples have reported good reliability and validity for this instrument. The NQ has been used as a representative measurement for evaluating Korean children’s dietary behaviors [33,34,35]. It comprises 19 items divided into five categories: balance (five items), diversity (three items), moderation (five items), regularity (three items), and practice (three items). The balance factors include the intake frequency of cooked rice with whole grains, fruits, cow milk, legumes, and eggs. The diversity factors include the number of vegetables in each meal and the frequency of intake of kimchi and diverse side dishes. The moderation factors include the frequency of eating sweet foods, fast foods, ramen, late-night snacks, and street food. The regularity factors include eating breakfast, meal regularity, and time spent watching TV and playing computer games. The practice factors include chewing well, checking nutrition labeling, and washing hands before meals. Most of the evaluation items use a five-point Likert scale, but some use three- or four-point Likert scales. The scores were calculated by entering each answer into the Child Nutrition Index Program (http://www.kns.or.kr/, accessed on 3 February 2020), which calculates a nutrition index, grades, and scores for the five areas, where higher scores indicate better eating behaviors. Kim et al. [33] identified the following diagnostic cut-off points for the five NQ factors to detect poor nutritional intake using the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis: balance (57), diversity (87), moderation (66), regularity (69), and practice (67). Scores below the cut-off points indicate poor nutritional intake. In our study, the NQ Cronbach’s alpha was 0.63.

- (2)

- Centers’ eating practices: Questionnaires were developed according to the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare’s guidelines for healthy eating [36] (see Appendix A). The questionnaire measures how food is consumed and how healthy diets are pursued in the centers using 10 items scored on a five-point scale, where higher scores indicated that the center provides more nutritious food and promotes healthier diets. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.771 in this study.

- (3)

- Service providers’ and cooks’ intentions regarding healthy eating practices: Self-reported questionnaires were used to measure the service providers’ and cooks’ awareness and risk perception, skills and self-efficacy, attitudes and outcome expectations, and social norms and support regarding healthy eating practices at the centers. This questionnaire was developed using the method suggested by Fishbein and Ajzen [37]. An example of an item related to skills and self-efficacy is, “I’m sure I can read the food labels,” and one related to social norms and support is, “People expect me to follow a healthy menu and recipe.” The questionnaire for the service providers and cooks comprised 22 and 24 items, respectively. Each item was scored on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (disagree) to 7 (agree), where higher scores indicated better intentions of desirable behavior-related healthy eating at the centers. In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha for service providers and cooks was 0.875 and 0.852, respectively.

2.3.2. Qualitative Phase

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Quantitative Phase

2.4.2. Qualitative Phase

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Quantitative Phase

2.5.2. Qualitative Phase

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings from the Survey

3.1.1. Diet Quality and Eating Behaviors

3.1.2. CCC Workers’ Perceptions of their Food Environments

3.2. Qualitative Findings from the Field Observation and Participant Interviews

3.2.1. Free Access to Unhealthy Foods but Limited Access to a Healthy Diet

I studied science very hard today, so I got a snack from the center in return for my hard work.(Obese girl; Center A, Participant observation statement)

What this center director usually buys is the cheap-for-quantity or bulky quantities. No matter the expiration date, there is lots of frozen meat in the fridge for a very long time.(A cook; Center B, Participant observation statement)

3.2.2. CCC Workers’ Poor Nutrition Literacy

Yesterday, in our menu, we had Spergularia marina Griseb (sebal herbs), which I have never heard of… It was tough for me to purchase this in the market, and the children did not eat it… The center director and I agreed that we should substitute the herb with spinach in our menu. The same is true for curled mallows included in the menu… Radish is good for steamed dishes because it makes you feel refreshed… This is the way I cook. People rarely use radish when cooking steamed dishes…(Center B, Individual interview with a cook)

I never try to use measuring cups, but this sort of thing must be taught in cooking schools… I am too old to learn it… If they fire me, I will have no place to work… Younger people attend cooking schools…(Center B, Individual interview with a cook)

3.2.3. Permissive or Indulgent Atmosphere: Only Seen at Centers A and B

Three seemingly fat children (one girl and two boys) gathered for a meal. More than two distributions had already been made. One of the boys licked the plate with his tongue to eat the soup. A child’s sister finished one helping and returned to her seat with as much rice and soup as was taken the last time. It appeared to be a lot, especially as she only took rice. The child was observed crawling in the kitchen and said, “I can’t move because I’m so full.” Further, the girl took five helpings of food.(Center A, Participant observation statement)

A teacher came to the room to eat and said, “Sir, time to eat.” The service provider replied, “Go ahead. I am in the middle of taking care of paperwork.”(Center A, Participant observation statement)

The child did not have any vegetables on his plate. The service provider said, “Why don’t you try some vegetables?” The child pretended not to hear this. When she tried to give him soup with vegetables, the boy said, “Nope. No vegetables!” The worker hesitated, but she asked, “Why not the vegetables?” The child only took the soup. When the service provider gave some vegetables with soup to another girl, she said, “Don’t put the vegetables on my plate!”(Center B, Participant observation statement)

3.2.4. Authoritarian Atmosphere: Only Seen at Center C

If you let children eat what they like, there’s a lot they don’t eat. I need to fix that… We try to make them eat even if they are about to vomit. It is not easy to do so if they are picky eaters! Especially for the lower grades; they are picky, and we try to fix their bad eating behavior all the time.(Service provider; Center C, Participant observation statement)

3.2.5. Inappropriate Social Support: Unhealthy Donated Foods

“Today, fish cake was donated to us. You can take it when you go home. One plastic bag per person! Do not leave it in your bag, otherwise it goes to your school tomorrow. As soon as you go home, please give it to your mother. Don’t forget to take the boiled fish paste with you, guys!” said workers(Center A, Participant observation statement)

3.2.6. Poor Parenting Style at Home Prompts Unhealthy Eating

The service provider said, “The children ate snacks before entering the center… Parents gave their children two thousand (Korean) won every day to assuage their regret for not taking good care of them… Then, the children ate snacks with the money… Some did not eat anything at the center and ate cup ramen at home. I warned parents not to give money to their children. They said that they cannot help it because they always feel sorry for them…”(Center B, Participant observation statement)

After the children were served several times, the child said, “Teacher, my sister is porky, and I am piggy. I have not eaten all day. I only ate a little bread at home.”(Center A, Participant observation statement)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In our center, we… | |||||

| 1. eat various foods, including rice, mixed grains, vegetables, fruits, milk and dairy products, meat, fish, eggs, and beans. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. avoid overeating and eat the right amount of food. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. eat less salty, less sweet, and less greasy food. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. drink plenty of water instead of sweet drinks. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. prepare only as much food as is planned. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. cook the food according to the menu. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. use our ingredients to enjoy our diet. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. distribute the proper amount at meals. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. dine together. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. cooperate in providing a healthy meal. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Appendix B

| Participants | Content of the Participant Observation | Interview Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Service Providers and Cooks | 1. What happens in the process of preparing lunch and snacks? (What do they do, interactions among people, etc.) (1) Do they have a menu and recipe for preparing lunch and snacks? 1-1. During the process, do the center director, social worker, and cook share their opinion? (2) Who provides the ingredients for meals and snacks? 2-1. Who goes shopping for food? 2-2. Do the service providers and cooks share their opinions in the process? 2. In the process of cooking for meals and snacks, what happens? (What do they do, interaction among people, etc.) (3) Who cooks the meals and snacks? 3-1. Do they cook based on the menu and recipe? 3-2. Does the cook dictate the cooking habits? 3-3. Do they use a measuring cup or a scale? 3-4. Does the center director, social worker, and cook discuss the taste of the food? 3. During the distribution and arrangement of the food and snacks, what happens? (Things that they do and interaction among people.) (4) Who distributes the meal? 4-1. Is the amount of food distributed to the children satisfactory? 4-2. When a child asks for more food, what is the typical reaction? (5) Do they eat together? 5-1. What is the atmosphere like when they eat together? (6) Do they teach eating habits to the children in the center? 6-1. If so, what is the focus of the teaching? | Based upon participant observation; interview will be carried out if necessary. |

| Children | 1. In the process of eating meals or snacks (before/middle/after), how did the children react? (behavior and interaction with others) | (1) What did the children do from entering the center to their leaving? (2) What was the most enjoyable time for the children to stay in the center? (3) What was not the most enjoyable time for the children to stay in the center? (4) How does mealtime proceed? (5) How does snack time proceed? (6) When was the most enjoyable mealtime? |

Appendix C

| Variables | Subcategory | N (%) or Mean ± SD | NQ Score | Balance | Moderation | Diversity | Regularity | Practice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | t/F (p) | Mean ± SD | t/F (p) | Mean ± SD | t/F (p) | Mean ± SD | t/F (p) | Mean ± SD | t/F (p) | Mean ± SD | t/F (p) | ||||

| Age (year) | Less than 8 8–10 11–13 14 and above | 46(13.2) 155(44.4) 107(30.7) 41(11.7) | 57.45 ± 11.70 59.35 ± 13.48 56.18 ± 14.28 59.54 ± 14.80 | 1.244 (0.294) | 51.08 ± 18.46 49.98 ± 20.07 49.39 ± 20.81 50.88 ± 23.75 | 0.090 (0.966) | 69.52 ± 20.42 68.64 ± 16.48 63.01 ± 17.09 61.85 ± 21.90 | 3.154 (0.025) * | 63.04 ± 23.67 67.58 ± 23.15 68.27 ± 25.17 73.25 ± 24.12 | 1.118 (0.342) | 60.38 ± 21.41 59.89 ± 22.33 53.73 ± 22.38 54.19 ± 25.31 | 1.985 (0.116) | 52.20 ± 18.25 58.00 ± 21.20 52.96 ± 21.13 60.58 ± 20.86 | 2.176 (0.091) | |

| Sex | Boy Girl | 175(50.1) 174(49.9) | 59.16 ± 13.47 58.00 ± 13.55 | 0.731 (0.465) | 59.16 ± 13.47 58.00 ± 13.55 | 1.373 (0.171) | 65.81 ± 18.81 68.60 ± 16.39 | 1.347 (0.179) | 68.22 ± 23.47 66.50 ± 25.29 | 0.595 (0.552) | 58.87 ± 22.75 57.64 ± 21.79 | 0.472 (0.637) | 56.69 ± 20.95 56.65 ± 20.94 | 0.014 (0.989) | |

| Socioeconomic status | Basic living security 1 Second-lowest income bracket 2 Childcare exception 3 Others 4 | 01(28.9) 43(12.3) 94(26.9) 111(31.7) | 57.00 ± 15.05 59.09 ± 12.11 58.41 ± 13.88 58.49 ± 12.90 | 0.317 (0.813) | 46.30 ± 23.62 50.26 ± 19.21 50.39 ± 18.59 52.98 ± 18.93 | 1.781 (0.151) | 67.13 ± 19.27 68.67 ± 21.32 68.29 ± 15.27 63.00 ± 17.18 | 1.843 (0.139) | 69.10 ± 25.20 68.75 ± 21.96 68.87 ± 25.06 65.12 ± 22.78 | 0.596 (0.618) | 56.07 ± 23.53 58.45 ± 24.39 55.79 ± 22.12 59.82 ± 21.59 | 0.676 (0.567) | 54.72 ± 22.14 56.89 ± 19.84 56.68 ± 22.49 55.88 ± 18.91 | 0.170 (0.916) | |

| Nutritional status | Under weight Normal Overweight Obese | 11(3.2) 220(63.0) 47(13.5) 71(20.3) | 61.15 ± 16.43 58.62 ± 13.17 56.12 ± 14.44 57.43 ± 13.78 | 0.622 (0.601) | 52.87 ± 25.30 50.63 ± 19.96 45.90 ± 21.47 50.41 ± 20.40 | 0.731 (0.534) | 73.04 ± 12.39 65.78 ± 18.40 65.94 ± 18.08 67.37 ± 17.24 | 0.606 (0.611) | 68.18 ± 22.95 67.77 ± 24.60 69.30 ± 21.98 66.50 ± 23.83 | 0.121 (0.948) | 57.16 ± 17.81 57.39 ± 22.31 55.33 ± 24.97 59.25 ± 22.96 | 0.265 (0.851) | 62.24 ± 23.55 57.59 ± 21.32 52.53 ± 18.94 51.79 ± 19.89 | 1.995 (0.115) | |

| Duration of CCC attendance | 6 months–less than 1 year 1 year–less than 3 years More than 3 years | 102(30.5) 103(36.8) 109(32.6) | 57.77 ± 13.32 57.93 ± 13.52 58.33 ± 14.49 | 0.046 (0.955) | 50.66 ± 19.63 47.57 ± 20.55 52.48 ± 21.20 | 1.661 (0.192) | 67.60 ± 18.42 67.70 ± 17.22 63.59 ± 17.91 | 1.859 (0.158) | 66.53 ± 23.41 67.09 ± 24.48 68.99 ± 24.17 | 0.297 (0.743) | 58.50 ± 21.68 58.44 ± 22.92 55.17 ± 23.15 | 0.755 (0.471) | 53.36 ± 20.00 56.67 ± 21.36 56.50 ± 21.22 | 0.806 (0.447) | |

| Weekly frequency of CCC attendance | 3–4 days 5–7 days | 31(9.3) 304(90.7) | 51.68 ± 15.73 58.70 ± 13.39 | 7.021 (0.008) * | 41.50 ± 22.67 50.88 ± 20.13 | 5.607 (0.018) * | 60.02 ± 19.88 67.04 ± 17.45 | 4.155 (0.042) * | 65.32 ± 22.27 67.73 ± 24.13 | 0.267 (0.606) | 50.34 ± 27.99 58.17 ± 21.93 | 3.182 (0.075) | 48.66 ± 21.31 56.54 ± 20.79 | 3.783 (0.053) | |

| Perceived body image | Skinny Normal Obese | 103(30.8) 144(43.0) 88(26.3) | 57.96 ± 13.61 59.65 ± 13.50 55.58 ± 13.94 | 2.324 (0.100) | 50.10 ± 20.51 52.51 ± 19.83 45.89 ± 21.17 | 2.767 (0.064) | 66.02 ± 19.43 65.94 ± 17.24 68.05 ± 16.80 | 0.422 (0.656) | 63.92 ± 26.18 70.86 ± 22.17 66.04 ± 23.61 | 2.666 (0.071) | 57.76 ± 22.08 57.90 ± 22.30 56.49 ± 24.04 | 0.112 (0.894) | 58.48 ± 20.99 56.67 ± 21.97 51.19 ± 18.36 | 3.010 (0.051) | |

| Perceived physical condition | Very healthy a Healthy b Unhealthy c Very unhealthy d | 104(31.0) 196(58.5) 33(9.9) 2(0.6) | 63.16 ± 14.29 56.29 ± 12.82 52.33 ± 13.20 58.15 ± 3.32 | 7.974 (0.000) * c < b < a | 54.79 ± 21.20 48.60 ± 18.98 43.34 ± 24.93 51.20 ± 7.07 | 3.924 (0.021) * | 67.75 ± 18.48 66.57 ± 17.75 62.48 ± 16.26 61.85 ± 2.05 | 0.736 (0.531) | 73.84 ± 23.84 64.97 ± 23.65 62.30 ± 23.23 64.15 ± 22.42 | 3.651 (0.013) * b < a | 60.61 ± 23.46 56.94 ± 21.74 49.03 ± 23.35 83.35 ± 11.81 | 3.048 (0.029) * | 63.15 ± 20.86 52.68 ± 20.27 51.97 ± 19.77 38.85 ± 7.85 | 6.687 (0.000) * b < a | |

References

- Satia, J.A. Diet-related disparities: Understanding the problem and accelerating solutions. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2009, 109, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desbouys, L.; Méjean, C.; De Henauw, S.; Castetbon, K. Socio-economic and cultural disparities in diet among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarro, S.; Lahdenperä, M.; Vahtera, J.; Pentti, J.; Lagström, H. Parental feeding practices and child eating behavior in different socioeconomic neighborhoods and their association with childhood weight. The STEPS Study. Health Place 2022, 74, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fismen, A.S.; Buoncristiano, M.; Williams, J.; Helleve, A.; Abdrakhmanova, S.; Bakacs, M.; Bergh, I.H.; Boymatova, K.; Duleva, V.; Fijałkowska, A.; et al. Socioeconomic differences in food habits among 6- to 9-year-old children from 23 countries-WHO European Childhood Obesity Surveillance Initiative (COSI 2015/2017). Obesity Rev. 2021, 22, e13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Psaltopoulou, T.; Hatzis, G.; Papageorgiou, N.; Androulakis, E.; Briasoulis, A.; Tousoulis, D. Socioeconomic status and risk factors for cardiovascular disease: Impact of dietary mediators. Hell. J. Cardiol. 2017, 58, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Consideration of the Evidence on Childhood Obesity for the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: Report of the ad hoc Working Group on Science and Evidence for Ending Childhood Obesity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/206549 (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Kim, S.Y.; Choo, J.A. Health behaviors and health-related quality of life among vulnerable children in a community. J. Korean Acad. Community Health Nurs. 2015, 26, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.B.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Kang, J.H.; Park, K.H.; Song, J. Association between parental socioeconomic level, overweight, and eating habits with diet quality in Korean sixth grade school children. Korean J. Nutr. 2011, 44, 416–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, S.C.; Shim, J.E. Nutritional status of toddlers and preschoolers according to household income level: Overweight tendency and micronutrient deficiencies. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2015, 9, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.W.; Yoon, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Gwon, A.R.; Gwon, J.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Jang, J.Y.; Jeong, H.H. A Study on the Nutrition Balance and the Prevention of Obesity for the Vulnerable; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2017.

- Umeda, M.; Oshio, T.; Fujii, M. The impact of the experience of childhood poverty on adult health-risk behaviors in Japan: A mediation analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ten Hoor, G.A.; Cho, J.; Kim, S. Service providers’ perspectives on barriers of healthy eating to prevent obesity among low-income children attending community childcare centers in South Korea: A qualitative study. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2020, 59, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T. Applying the socio-ecological model to improving fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African Americans. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahunt, A.; Conway, M.C.; O’Brien, E.C.; Geraghty, A.A.; O’Keeffe, L.M.; O’Reilly, S.L.; McDonnell, C.M.; Kearney, P.M.; Mehegan, J.; McAuliffe, F.M. Ecological factors and childhood eating behaviours at 5 years of age: Findings from the ROLO longitudinal birth cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costarelli, V.; Michou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Lionis, C. Parental health literacy and nutrition literacy affect child feeding practices: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Health 2022, 28, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, H.D.; Kennett, A.R.; Kerling, E.H.; Yu, Q.; Gajewski, B.; Ptomey, L.T.; Sullivan, D.K. Assessing the nutrition literacy of parents and its relationship with child diet quality. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.G.; Lee, H.Y. A Study on Model Development of Kongbubang for the Youth. Youth Welf. Res. 2001, 3, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Introduction on Support Projects for Community Child Care Center. 2019. Available online: http://www.hjy.kr/user/Information05_view.php?num=73&cur_page=1&schSel=title&schStr=&filePath1=./Information05.php&boardType=1 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Statistics Report on Community Child Care Centers. 2019. Available online: https://icareinfo.go.kr/info/research/researchDetail.do (accessed on 5 November 2022).

- Kim, Y. Children’s Meal Project Guide; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2011; pp. 1–3.

- Seon, M.J.; Cho, H.Y. The mixed methods study on the community child center services and school adaptation of vulnerable adolescents. Forum Youth Cult 2019, 61, 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.H.; Hong, S.W.; Yoo, S.G. Path analysis on impacts of service usefulness of community children-center on school adjustment among children in poverty: Focusing on examination of direct and indirect effects. J. Comm. Welf. 2016, 59, 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.H.; Shin, S.H. The longitudinal relationship among academic achievement, self-esteem, and depression of children in community child center. Educ. Child. 2019, 28, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Gwak, N.J.; Kim, A.J.N.; Jo, Y.Y. Improving National Diet by Promoting the Nutrition Management of Institutional Food Service; Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2010; pp. 1–214. Available online: https://www.kihasa.re.kr/api/external/viewer/doc.html?fn=10185:12_1032.pdf&rs=/api/external/viewer/upload/kihasaold/report (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Jung, I.J.; Kim, M.S.; Lim, J.K. A Study on the Improvement of Care Service for Community Child Care Center; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2017.

- Park, J.; Park, C.; Kim, S.; Ten Hoor, G.A.; Hwang, G.; Hwang, Y.S. Who are the assistant cooks at the community child centers in South Korea? Focus group interviews with workfare program participants. Child Health Nurs. Res. 2020, 26, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Lee, I.S. Assessment of nutritional status of children in community child center by nutrition quotient (NQ)-Gyeongiu. J. East Asian Soc. Diet Life 2015, 25, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Yeoh, Y. Status of meal serving and nutritional quality of foods served for children at community child centers in Korea. J. East Asian Soc. Diet Life 2015, 25, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.A. Evaluation of dietary behavior and nutritional status of children at community child center according to family meal frequency in Gyoengbuk Area using Nutrition Quotient. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 48, 1280–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health & Welfare. Community Childcare Center Support Project Information; Ministry of Health & Welfare: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2022. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb0601vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=03160501&SEARCHKEY=TITLE&SEARCHVALUE=2022&page=1&CONT_SEQ=369674 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Kang, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Kwon, S.; Choi, Y.; Chung, H.; Kwak, T.; Cho, Y. Selecting items of a food behavior checklist for the development of Nutrition Quotient (NQ) for children. Korean J. Nutr. 2012, 45, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Kwon, S.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, Y.S.; Chung, H.R.; Kwak, T.K.; Park, J.; Kang, M.H. Development of a Nutrition Quotient (NQ) equation modeling for children and the evaluation of its construct validity. J. Nutr. Health 2012, 45, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.A.; Kim, H.S. Food behavior using the nutrition quotient and vegetable preferences of elementary school students in the metropolitan area. J. Korean Diet. Assoc. 2021, 27, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.M.; Han, Y.; Lee, K.A. Analysis of the types of eating behavior affecting the nutrition of preschool children: Using the Dietary Behavior Test (DBT) and the Nutrition Quotient (NQ). J. Nutr. Health 2019, 52, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare; The Korean Dietetic Association. The National Common Dietary Guidelines for the People. 2016. Available online: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/jb/sjb030301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=03&MENU_ID=0320&CONT_SEQ=332757 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Ryu, H. Comparison of nutritional status and eating behavior of Korean and Chinese children using the Nutrition Quotient (NQ). Korean Soc. Community Nutr. 2017, 22, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.M.; Kim, H.S. Evaluation of dietary behavior of elementary school students in the Gyunggi using Nutrition Quotient. J Korea Contents. Assoc. 2019, 19, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, Y.H. Evaluation of food behavior and nutritional status of preschool children in Nowon-gu of Seoul by using nutrition quotient (NQ). Korean J. Community Nutr. 2014, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.K.; Kim, J.H.; Woo, S.H. Verifying effectiveness on physical activity and nutrition program for obesity management of children from low income family. Korean J. Sport. Sci. 2019, 28, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscum, P.; Sharma, M. After-school based obesity prevention interventions: A comprehensive review of the literature. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 1438–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, S.; McClinton-Powell, L.; Solomon, M.; Davis, D.; Lipton, R.; Darukhanavala, A.; Steenes, A.; Selvaraj, K.; Gielissen, K.; Love, L.; et al. Power-up: A collaborative after-school program to prevent obesity in African American children. Prog. Community Health Partn. Res. Educ. Action 2011, 5, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, & Labour and Welfare. Guidelines for Dining in Children’s Welfare Facilities. 2010. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2010/03/dl/s0331-10a-015.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Jo, A.J. The food delivery services of community child centers for poor children. Health Welf. Pol. Forum 2008, 5, 43–54. Available online: https://www.kihasa.re.kr/publish/regular/hsw/view?seq=21570&volume=20282 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Teaching good table manners to kids. Kids Eat Right. 2014. Available online: https://www.eatright.org/food/planning/meals-and-snacks/end-mealtime-battles (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Galloway, A.T.; Fiorito, L.M.; Francis, L.A.; Birch, L.L. ‘Finish your soup’: Counterproductive effects of pressuring children to eat on intake and affect. Appetite 2006, 46, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J.S.; Kremers, S.P.; Stafleu, A.; Dagnelie, P.C.; de Vries, N.K.; Thijs, C. Child-care environment and dietary intake of 2- and 3-year-old children. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2010, 23, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, A.; Vaughn, A.E.; Fallon, M.; Hennessy, E.; Burney, R.; Østbye, T.; Ward, D.S. Providers’ response to child eating behaviors: A direct observation study. Appetite 2016, 105, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, D.A.; McBride, B.A.; Speirs, K.E.; Donovan, S.M.; Cho, H.K. Predictors of head start and child-care providers’ healthful and controlling feeding practices with children aged 2 to 5 years. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2014, 114, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin Neelon, S.E.; Briley, M.E. American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Benchmarks for nutrition in child care. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2011, 111, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourshahidi, L.K.; Kerr, M.A.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Livingstone, M.B.E. Influencing and modifying children’s energy intake: The role of portion size and energy density. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L.; Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O. Right sizing prevention. Food portion size effects on children’s eating and weight. Appetite 2015, 88, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, L.A. Feeding practices and parenting: A pathway to child health and family happiness. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2019, 74, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carper, J.L.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Young girl’s emerging dietary restraint and disinhibition are related to parental control in child feeding. Appetite 2000, 35, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, J.; Haycraft, E.; Lytle, L.; Nicklaus, S.; Kok, F.J.; Merdji, M.; Fisberg, M.; Moreno, L.A.; Goulet, O.; Hughes, S.O. Nurturing Children’s Healthy Eating: Position statement. Appetite 2019, 137, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCosta, P.; Møller, P.; Frøst, M.B.; Olsen, A. Changing children’s eating behaviour-A review of experimental research. Appetite 2017, 113, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, M.; Jomaa, L.; Eagleton, S.; Savage, J. Head Start Parents With or Without Food Insecurity and With Lower Food Resource Management Skills Use Less Positive Feeding Practices in Preschool-Age Children. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risica, P.M.; Amin, S.; Ankoma, A.; Lawson, E. The food and activity environments of childcare centers in Rhode Island: A directors’ survey. BMC Nutr. 2016, 2, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Kim, Y.O. Effect on food choice satisfaction and food cost reduction of food donation program. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2014, 14, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, H.J. On the possibility and limitation of food solidarity through the food bank project. J. Soc. Res. 2013, 14, 31–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.; Webb, K.; Ross, M.; Crawford, P.; Hudson, H.; Hecht, K. Nutrition-Focused Food Banking; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/FoodBanking1.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Story, M.; Kaphingst, K.M.; Robinson-O’Brien, R.; Glanz, K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: Policy and environmental approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsey, E.W.; Hecht, A.A.; Dunn, C.G.; Levi, R.; Read, M.A.; Smith, C.; Niesen, P.; Seligman, H.K.; Hager, E.R. School closures during COVID-19: Opportunities for innovation in meal service. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcaterra, V.; Verduci, E.; Vandoni, M.; Rossi, V.; Di Profio, E.; Carnevale Pellino, V.; Tranfaglia, V.; Pascuzzi, M.C.; Borsani, B.; Bosetti, A.; et al. Telehealth: A useful tool for the management of nutrition and exercise programs in pediatric obesity in the COVID-19 era. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Research | Subjects | Variables | N (%) or Mean (±SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative study | Children (N = 349) | Age (year) | 10.2 (±2.4) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Boy | 175 (50.1) | |||

| Girl | 174 (49.9) | |||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Basic living security 1 | 101 (28.9) | |||

| Second-lowest income bracket 2 | 43 (12.3) | |||

| Childcare exception 3 | 94 (26.9) | |||

| Others 4 | 111 (31.7) | |||

| Nutritional status | ||||

| Underweight | 11 (3.2) | |||

| Normal | 220 (63.0) | |||

| Overweight | 47 (13.5) | |||

| Obese | 71 (20.3) | |||

| Duration of CCC attendance | ||||

| 6 months–less than 1 year | 102 (30.5) | |||

| 1 year–less than 3 years | 103 (36.8) | |||

| Longer than 3 years | 109 (32.6) | |||

| Weekly frequency of CCC attendance | ||||

| 3 or 4 days | 31 (9.3) | |||

| 5–7 days | 304 (90.7) | |||

| Perceived body image | ||||

| Skinny | 103 (30.8) | |||

| Normal | 144 (43.0) | |||

| Obese | 88 (26.3) | |||

| Perceived physical condition | ||||

| Very healthy | 104 (31.0) | |||

| Healthy | 196 (58.5) | |||

| Unhealthy | 33 (9.9) | |||

| Very unhealthy | 2 (0.6) | |||

| Service providers (N = 34) | Age (year) | 45.5 (±11.2) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 4 (11.8) | |||

| Female | 30 (88.2) | |||

| Education | ||||

| College | 26 (76.5) | |||

| Graduate school | 7 (20.6) | |||

| Other | 1 (2.9) | |||

| Length of service at current CCC (month) | 52.8 (±40.4) | |||

| Cooks (N = 15) | Age (year) | 53.9 (±6.1) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 15 (100) | |||

| Education | ||||

| Elementary school | 3 (20) | |||

| Middle school | 1 (6.7) | |||

| High school | 11 (73.3) | |||

| Period of working at current CCC (month) | 22.8 (±20.4) | |||

| Qualitative study | CCCs ** (N = 3) | Number of children | Center A | 24 |

| Center B | 29 | |||

| Center C | 31 | |||

| Number of workers | Center A | 3 | ||

| Center B | 3 | |||

| Center C | 4 | |||

| Current CCC operation period (year) | Center A | 15 | ||

| Center B | 14 | |||

| Center C | 9 | |||

| Item | Service Providers (n = 34) | Cooks (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ** | SD | Mean ** | SD | |

| 1. Our center promotes a balanced diet. | 4.53 | 0.507 | 4.86 * | 0.363 |

| 2. Our center discourages overeating. | 4.15 | 0.857 | 4.60 | 0.507 |

| 3. Our center rarely provides unhealthy foods (i.e., salty, sweet, or greasy food.) | 4.44 | 0.660 | 4.80 | 0.414 |

| 4. Our center provides plenty of drinking water. | 4.12 | 0.769 | 4.60 | 0.737 |

| 5. Our center prepares only as much food as planned. | 4.35 | 0.646 | 4.73 | 0.594 |

| 6. Our center cooks food according to the menu. | 4.59 | 0.557 | 4.73 | 0.458 |

| 7. Our center uses fresh food ingredients. | 4.50 | 0.663 | 4.80 | 0.414 |

| 8. Our center distributes the proper number of meals for children. | 4.35 | 0.485 | 4.93 | 0.258 |

| 9. At our center everyone dines together. | 4.59 | 0.783 | 4.60 | 1.056 |

| 10. Staff at our center help each other to provide healthy food for children. | 4.50 | 0.564 | 4.93 | 0.704 |

| Item | Service Providers (n = 34) | Cooks (n = 15) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean * | SD | Mean * | SD | |

| 1. Monitoring children’s eating habits is important. | 6.41 | 0.701 | 6.00 | 1.464 |

| 2. Monitoring the food environment of the center is necessary. | 6.00 | 0.921 | 5.67 | 1.496 |

| 3. Monitoring of the snacks and food eaten by children at the center is needed. | 6.03 | 0.870 | 5.93 | 1.223 |

| 4. I must make sure that the children eat healthily at the center. | 6.68 | 0.589 | 6.80 | 0.414 |

| 5. For obesity prevention and health promotion, healthy eating must be ensured by the center. | 6.26 | 1.024 | 6.73 | 0.458 |

| 6. People expect me to make sure that children eat healthily at the center. | 6.26 | 0.828 | 6.53 | 0.834 |

| 7. For healthy eating, children need support from a trusted institution. | 6.44 | 0.824 | 6.87 | 0.352 |

| 8. I understand the need for a healthy meal. | 6.65 | 0.597 | 6.67 | 0.488 |

| 9. I can read the menu and the recipe correctly. | 5.94 | 0.886 | 6.53 | 0.743 |

| 10. People expect me to follow a healthy menu. | 6.15 | 0.784 | 6.67 | 0.488 |

| 11. I can comply with a healthy menu and recipe. | 5.91 | 0.965 | 6.53 | 0.743 |

| 12. I can purchase the proper amount of food ingredients for the menu. | 6.06 | 0.814 | - | - |

| 13. I can separate harmful foods from foods donated to the center. | 5.85 | 1.048 | - | - |

| 14. I can read the food labels. | 5.68 | 1.007 | 6.53 | 0.640 |

| 15. I can discuss food taste with the center’s members on a regular basis. | 6.18 | 0.834 | - | - |

| 16. I can feed the center’s children with the proper amount of food. | 6.09 | 0.933 | 6.87 | 0.352 |

| 17. I know how to say no to a child who wants a second serving of food at the center. | 5.24 | 1.597 | 5.67 | 1.234 |

| 18. I know that all members of the center can dine together. | 5.97 | 1.314 | 5.80 | 1.781 |

| 19. For healthy eating, children need to eat together. | 6.47 | 0.825 | 6.53 | 0.834 |

| 20. People expect me to eat with children at the center. | 5.88 | 1.008 | 5.87 | 1.727 |

| 21. Children need to follow healthy dietary behaviors at the center. | 6.59 | 0.609 | 6.87 | 0.352 |

| 22. I am sure that children eat healthy foods at the center. | 6.18 | 0.834 | 6.73 | 0.594 |

| 23. I can distinguish healthy food ingredients for cooking. | - | - | 6.80 | 0.414 |

| 24. I do not cook unhealthy foods (i.e., salty, spicy, sweet ones). | - | - | 6.67 | 0.488 |

| 25. I can make healthy and tasty food(s) for children at the center. | - | - | 6.53 | 0.834 |

| 26. I can discuss cooking with the service providers. | - | - | 6.60 | 0.910 |

| 27. I do not follow unhealthy cooking methods. | - | - | 6.87 | 0.352 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.; Baek, S.; Hwang, G.; Park, C.; Hwang, S. Diet-Related Disparities and Childcare Food Environments for Vulnerable Children in South Korea: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1940. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081940

Park J, Baek S, Hwang G, Park C, Hwang S. Diet-Related Disparities and Childcare Food Environments for Vulnerable Children in South Korea: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(8):1940. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081940

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Jiyoung, Seolhyang Baek, Gahui Hwang, Chongwon Park, and Sein Hwang. 2023. "Diet-Related Disparities and Childcare Food Environments for Vulnerable Children in South Korea: A Mixed-Methods Study" Nutrients 15, no. 8: 1940. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081940

APA StylePark, J., Baek, S., Hwang, G., Park, C., & Hwang, S. (2023). Diet-Related Disparities and Childcare Food Environments for Vulnerable Children in South Korea: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients, 15(8), 1940. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081940