Impact of a Switch to Plant-Based Foods That Visually and Functionally Mimic Animal-Source Meat and Dairy Milk for the Australian Population—A Dietary Modelling Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source and Preparation

2.2. Identification of ‘Easily Swappable’ Dairy Milk and Animal-Source Meat and ‘Key Nutrients’

2.3. Development of the Dietary Transition Scenarios

2.4. Dietary Modelling

3. Results

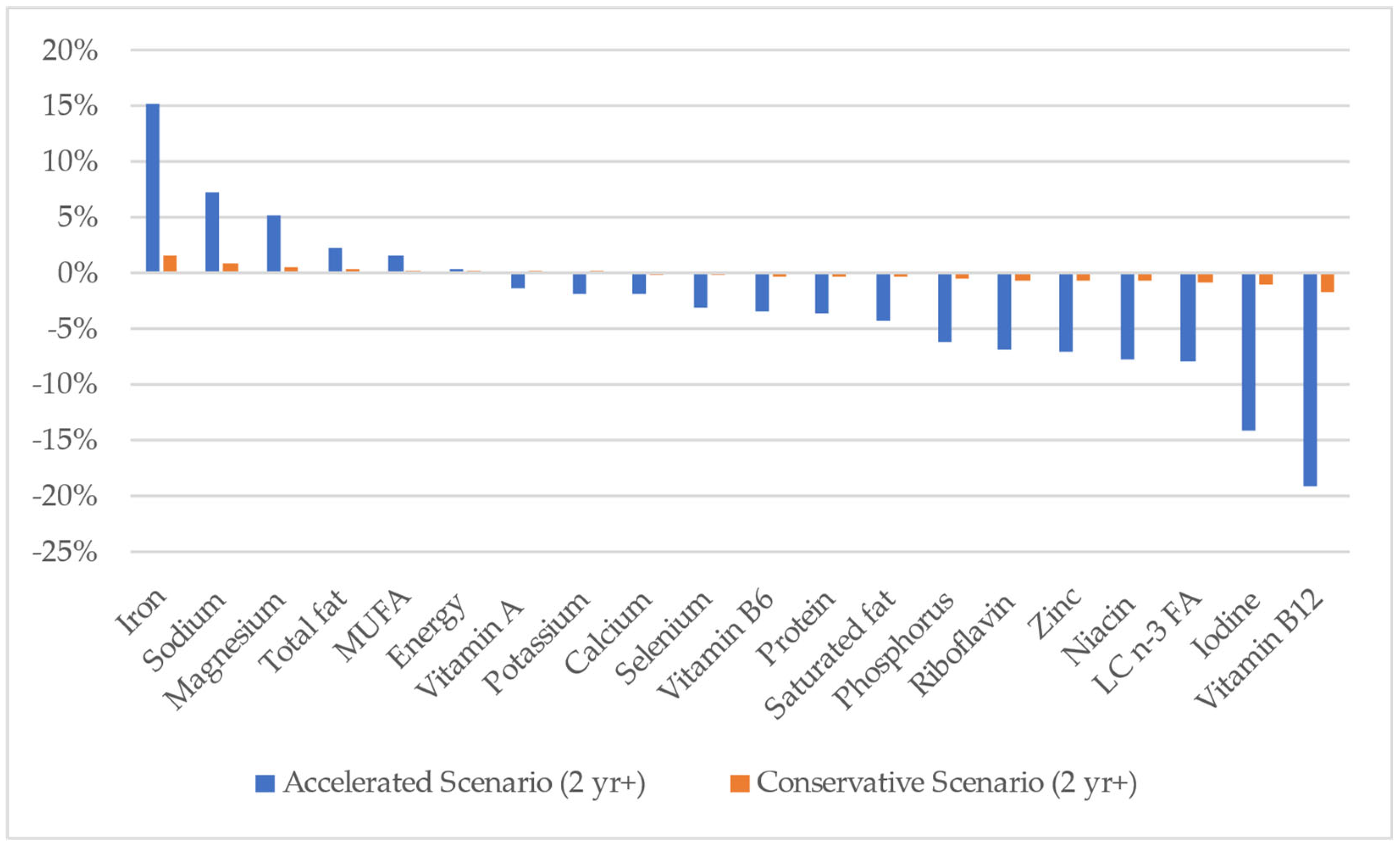

3.1. Combined Meat and Milk Scenarios

3.2. Meat Scenarios

3.3. Milk Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pörtner, H.; Roberts, D.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Contribution of Working Group II to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The Global Movement—Meatless Monday. Available online: https://www.mondaycampaigns.org/meatless-monday/the-global-movement (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Clark, M.; Springmann, M.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D.; Macdiarmid, J.I.; Fanzo, J.; Bandy, L.; Harrington, R.A. Estimating the Environmental Impacts of 57,000 Food Products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120584119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key Statistics—OD5256 Soy and Almond Milk Production in Australia—MyIBISWorld. Available online: https://my.ibisworld.com/au/en/industry-specialized/od5256/key-statistics (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Sridhar, K.; Bouhallab, S.; Croguennec, T.; Renard, D.; Lechevalier, V. Recent Trends in Design of Healthier Plant-Based Alternatives: Nutritional Profile, Gastrointestinal Digestion, and Consumer Perception. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtain, F.; Grafenauer, S. Plant-Based Meat Substitutes in the Flexitarian Age: An Audit of Products on Supermarket Shelves. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Frontier. 2020 State of the Industry: Australia’s Plant-Based Meat Sector; Food Frontier: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Apparent Consumption of Selected Foodstuffs, Australia, 2020–2021 Financial Year Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/apparent-consumption-selected-foodstuffs-australia/2020-21 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Van Vliet, S.; Kronberg, S.L.; Provenza, F.D. Plant-Based Meats, Human Health, and Climate Change. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, H.; Shahid, M.; Gaines, A.; McKenzie, B.L.; Alessandrini, R.; Trieu, K.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Rosewarne, E.; Coyle, D.H. The Nutritional Profile of Plant-Based Meat Analogues Available for Sale in Australia. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnack, L.; Mork, S.; Valluri, S.; Weber, C.; Schmitz, K.; Stevenson, J.; Pettit, J. Nutrient Composition of a Selection of Plant-Based Ground Beef Alternative Products Available in the United States. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 2401–2408.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimarco, A.; Springfield, S.; Petlura, C.; Streaty, T.; Cunanan, K.; Lee, J.; Fielding-Singh, P.; Carter, M.M.; Topf, M.A.; Wastyk, H.C.; et al. A Randomized Crossover Trial on the Effect of Plant-Based Compared with Animal-Based Meat on Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in Generally Healthy Adults: Study with Appetizing Plantfood—Meat Eating Alternative Trial (SWAP-MEAT). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1188–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Stewart, C.; Astbury, N.M.; Cook, B.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Replacing Meat with Alternative Plant-Based Products (RE-MAP): A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Multicomponent Behavioral Intervention to Reduce Meat Consumption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 115, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Hughes, J.; Grafenauer, S. Got Mylk? The Emerging Role of Australian Plant-Based Milk Alternatives as A Cow’s Milk Substitute. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Fresán, U. International Analysis of the Nutritional Content and a Review of Health Benefits of Non-Dairy Plant-Based Beverages. Nutrients 2021, 13, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. How Well Do Plant Based Alternatives Fare Nutritionally Compared to Cow’s Milk? J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, M.E.; Tarrado Ribes, A.; Reynolds, R.; Kliem, K.; Stergiadis, S. A Comparative Assessment of the Nutritional Composition of Dairy and Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives Available for Sale in the UK and the Implications for Consumers’ Dietary Intakes. Food Res. Int. 2021, 148, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, K.M.; McCormick, D.P. A Nutritional Comparison of Cow’s Milk and Alternative Milk Products. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1067–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Baker, R.D.; Baker, S.S. A Comparison of the Nutritional Value of Cow’s Milk and Nondairy Beverages. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Food Composition Database. Browse Foods. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/afcd/Pages/foodsearch.aspx (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Plant-Based Producers Have Demographics on Their Side—Euromonitor.com. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/article/plant-based-producers-have-demographics-on-their-side (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Knaapila, A.; Michel, F.; Jouppila, K.; Sontag-Strohm, T.; Piironen, V. Millennials’ Consumption of and Attitudes toward Meat and Plant-Based Meat Alternatives by Consumer Segment in Finland. Foods 2022, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yantcheva, B.; Golley, S.; Topping, D.; Mohr, P. Food Avoidance in an Australian Adult Population Sample: The Case of Dairy Products. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1616–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Nutrition First Results—Food and Nutrients, 2011–2012; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Temme, E.H.M.; Bakker, H.M.E.; Seves, S.M.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Dekkers, A.L.; van Raaij, J.M.A.; Ocké, M.C. How May a Shift towards a More Sustainable Food Consumption Pattern Affect Nutrient Intakes of Dutch Children? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2468–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparast, H.; Islam, N.; Shafiee, M.; Dan Ramdath, D. Increasing Plant-Based Meat Alternatives and Decreasing Red and Processed Meat in the Diet Differentially Affect the Diet Quality and Nutrient Intakes of Canadians. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tso, R.; Forde, C.G. Unintended Consequences: Nutritional Impact and Potential Pitfalls of Switching from Animal- to Plant-Based Foods. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomé, M.; Huneau, J.F.; le Baron, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Fouillet, H.; Mariotti, F. Substituting Meat or Dairy Products with Plant-Based Substitutes Has Small and Heterogeneous Effects on Diet Quality and Nutrient Security: A Simulation Study in French Adults (INCA3). J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieger, J.A.; Johnson, B.J.; Wycherley, T.P.; Golley, R.K. Evaluation of Simulation Models That Estimate the Effect of Dietary Strategies on Nutritional Intake: A Systematic Review. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Microdata; TableBuilder: Australian Health Survey: Nutrition and Physical Activity|Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/microdata-tablebuilder/available-microdata-tablebuilder/australian-health-survey-nutrition-and-physical-activity (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- About AUSNUT 2011–2013. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/ausnut/Pages/about.aspx (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Lawrence, S.; King, T. Meat the Alternative: 2019 State of the Industry; Food Frontier: Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey Analytical Program. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/science/monitoringnutrients/Pages/2019-National-Nutrition-and-Physical-Activity-Survey-analytical-program.aspx (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Food Frontier. State of the Industry Australia’s Plant-Based Meat Sector Cellular Agriculture; Food Frontier: Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: Usual Nutrient Intakes, 2011–2012. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/australian-health-survey-usual-nutrient-intakes/latest-release#key-findings (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Meyer, B.J. Australians Are Not Meeting the Recommended Intakes for Omega-3 Long Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Results of an Analysis from the 2011–2012 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Nutrients 2016, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Available online: https://www.nrv.gov.au/home (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Seves, S.M.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Biesbroek, S.; Temme, E.H.M. Are More Environmentally Sustainable Diets with Less Meat and Dairy Nutritionally Adequate? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2050–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Population Health Development Principal Committee of the Australian Health Ministers Advisory Committee. The Prevalence and Severity of Iodine Deficiency in Australia; Australian Goverenment Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2007. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/code/proposals/documents/The%20prevalence%20and%20severity%20of%20iodine%20deficiency%20in%20Australia%2013%20Dec%202007.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Hynes, K.L.; Seal, J.A.; Otahal, P.; Oddy, W.H.; Burgess, J.R. Women Remain at Risk of Iodine Deficiency during Pregnancy: The Importance of Iodine Supplementation before Conception and Throughout Gestation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.A.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M.; de Jersey, S.; Collins, C.E.; Gallo, L.; Rollo, M.; Borg, D.; Dekker Nitert, M.; Truby, H.; Barrett, H.L.; et al. Exploring the Diets of Mothers and Their Partners during Pregnancy: Findings from the Queensland Family Cohort Pilot Study. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 79, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, K.; Thomas, E.; Nugent, A.; Woodside, J.; Hart, K.; Bath, S.C. Iodine Fortification of Plant-Based Dairy and Fish Alternatives: The Effect of Substitution on Iodine Intake Based on a Market Survey in the UK. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 129, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hatch-Mcchesney, A.; Lieberman, H.R. Iodine and Iodine Deficiency: A Comprehensive Review of a Re-Emerging Issue. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.A.; Cowell, C.T.; Emder, P.J.; Learoyd, D.L.; Chua, E.L.; Sinn, J.; Jack, M.M. Iodine Toxicity from Soy Milk and Seaweed Ingestion Is Associated with Serious Thyroid Dysfunction. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 193, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helen Huang, H.; Cohen, A.A.; Gaudreau, P.; Auray-Blais, C.; Allard, D.; Boutin, M.; Reid, I.; Turcot, V.; Presse, N. Vitamin B-12 Intake from Dairy but Not Meat Is Associated with Decreased Risk of Low Vitamin B-12 Status and Deficiency in Older Adults from Quebec, Canada. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, K.L.; Rich, S.; Rosenberg, I.; Jacques, P.; Dallal, G.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Selhub, J. Plasma Vitamin B-12 Concentrations Relate to Intake Source in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, Y. Vitamin B-12 Requirements in Older Adults—Increasing Evidence Substantiates the Need to Re-Evaluate Recommended Amounts and Dietary Sources. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 2317–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.; Block, R.; Mousa, S.A. Omega-3 Fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health Benefits Throughout Life. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howe, P.; Meyer, B.; Record, S.; Baghurst, K. Dietary Intake of Long-Chain ω-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Contribution of Meat Sources. Nutrition 2006, 22, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vahmani, P.; Ponnampalam, E.N.; Kraft, J.; Mapiye, C.; Bermingham, E.N.; Watkins, P.J.; Proctor, S.D.; Dugan, M.E.R. Bioactivity and Health Effects of Ruminant Meat Lipids. Invited Review. Meat Sci. 2020, 165, 108114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Brunin, J.; Fouillet, H.; Dussiot, A.; Mariotti, F.; Langevin, B.; Berthy, F.; Touvier, M.; Julia, C.; et al. Nutritionally Adequate and Environmentally Respectful Diets Are Possible for Different Diet Groups: An Optimized Study from the NutriNet-Santé Cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 116, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogoy, K.M.C.; Sun, B.; Shin, S.; Lee, Y.; Li, X.Z.; Choi, S.H.; Park, S. Fatty Acid Composition of Grain- and Grass-Fed Beef and Their Nutritional Value and Health Implication. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2022, 42, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnampalam, E.N.; Mann, N.J.; Sinclair, A.J. Effect of Feeding Systems on Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Conjugated Linoleic Acid and Trans Fatty Acids in Australian Beef Cuts: Potential Impact on Human Health. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 15, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dussiot, A.; Fouillet, H.; Wang, J.; Salomé, M.; Huneau, J.-F.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Mariotti, F. Modeled Healthy Eating Patterns Are Largely Constrained by Currently Estimated Requirements for Bioavailable Iron and Zinc—A Diet Optimization Study in French Adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 15, 958–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguiliouk, E.; Glenn, A.J.; Nishi, S.K.; Chiavaroli, L.; Seider, M.; Khan, T.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Mejia, S.B.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; et al. The Effect of the Meat Factor in Animal-Source Foods on Micronutrient Absorption: A Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S308–S319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer Labba, I.C.; Steinhausen, H.; Almius, L.; Bach Knudsen, K.E.; Sandberg, A.S. Nutritional Composition and Estimated Iron and Zinc Bioavailability of Meat Substitutes Available on the Swedish Market. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, R.P.; Rafferty, K.; Bierman, J. Not All Calcium-Fortified Beverages Are Equal: Nutrition Today. Nutr. Today 2005, 40, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Shkembi, B.; Huppertz, T. Calcium Absorption from Food Products: Food Matrix Effects. Nutrients 2022, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, R.; Barker, S.; Falkeisen, A.; Gorman, M.; Knowles, S.; McSweeney, M.B. An Investigation into Consumer Perception and Attitudes towards Plant-Based Alternatives to Milk. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Food Information Council. A Consumer Survey on Plant Alternatives to Animal Meat; International Food Information Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, L.; Arcand, J.A.; L’Abbe, M.; Deng, M.; Duhaney, T.; Campbell, N. Accuracy of Canadian Food Labels for Sodium Content of Food. Nutrients 2014, 6, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.M.; James, A.P.; Ip, H.I.; Dunlop, E.; Cunningham, J.; Adorno, P.; Dabos, G.; Black, L.J. Comparison of Measured and Declared Vitamin D Concentrations in Australian Fortified Foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report—Climate Assembly UK. Available online: https://www.climateassembly.uk/report/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Retail Sales Data: Plant-Based Meat, Eggs, Dairy|GFI. Available online: https://gfi.org/marketresearch/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The Healthiness and Sustainability of National and Global Food Based Dietary Guidelines: Modelling Study. BMJ 2020, 370, m2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Consumer Perceptions of Plant-Based Meats and Food Labels|University of Technology Sydney. Available online: https://www.uts.edu.au/isf/explore-research/projects/australian-consumer-perceptions-plant-based-meats-and-food-labels (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code—Schedule 9—Mandatory Advisory Statements. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2021C00195 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Islam, N.; Shafiee, M.; Vatanparast, H. Trends in the Consumption of Conventional Dairy Milk and Plant-Based Beverages and Their Contribution to Nutrient Intake among Canadians. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 34, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Food and AUSNUT Codes [33] | Base Case Mean Daily Intake (g) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population (2 Years and Over) | Young Children (2–3 Years) | Young Women (19–30 Years) | Young Men (19–30 Years) | Older Adults (71 Years and Over) | ||

| ‘Easily Swappable Animal-Source Meat’ | Beef 18101001–18101273 (mainly steak, fillet and mince) | 18.7 | 6.9 | 14.2 | 22.2 | 19.4 |

| Chicken 18301001–18301087 (mainly breast, drumsticks, wings, thighs and fillets) | 24.3 | 12.7 | 20.9 | 42.5 | 21.4 | |

| Sausages 18501001–18503009 (beef, chicken or pork sausages) | 10.2 | 8.0 | 6.8 | 13.4 | 9.3 | |

| Total meat (beef, chicken and sausages) | 53.2 | 27.5 | 41.9 | 78.1 | 50.2 | |

| ‘Easily Swappable Dairy Milk’ | Dairy milk 19101001–19105005 (fluid cows’ milk) | 143.4 | 274.2 | 115.0 | 158.7 | 147.9 |

| Nutrient | ‘Easily Swappable Animal-Source Meat’ 2 | ‘Easily Swappable Dairy Milk’ 3 | Combined ‘Easily Swappable Dairy Milk and Animal-Source Meat’ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Intake | % Total Intake | Mean Intake | % Total Intake | Mean Intake | % Total Intake | |

| Energy (kJ) | 441 | 5.2 | 365 | 4.3 | 806 | 9.5 |

| Protein (g) | 13.4 | 15.3 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 18.7 | 21.4 |

| Fat (g) | 5.5 | 7.5 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 9.1 | 12.5 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 2.0 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 8.4 | 4.4 | 15.6 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 2.5 | 9.0 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 12.4 |

| n-3 long-chain fatty acids (mg) | 21.4 | 8.6 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 23.7 | 9.5 |

| Vitamin A retinol equivalents (µg) | 7.7 | 1.0 | 51.9 | 6.4 | 59.6 | 7.4 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.1 | 4.8 | 0.3 | 15.8 | 0.4 | 20.6 |

| Niacin derived equivalents (mg) | 5.3 | 13.5 | 1.5 | 3.8 | 6.8 | 17.3 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.2 | 10.7 | 0.1 | 5.7 | 0.2 | 16.4 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 0.6 | 13.9 | 0.9 | 20.7 | 1.5 | 34.6 |

| Calcium (mg) | 5.6 | 0.7 | 170.0 | 21.1 | 175.6 | 21.8 |

| Iodine (µg) | 1.0 | 0.6 | 33.1 | 19.3 | 34.1 | 19.9 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.8 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 7.4 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 13.0 | 4.1 | 16.4 | 5.1 | 29.3 | 9.2 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 125 | 8.8 | 142 | 10.0 | 267 | 18.8 |

| Potassium (mg) | 160 | 5.7 | 228 | 8.1 | 388 | 13.9 |

| Selenium (µg) | 9.7 | 11.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 11.3 | 13.2 |

| Sodium (mg) | 131 | 5.5 | 58.9 | 2.4 | 190 | 7.9 |

| Zinc (mg) | 1.6 | 15.5 | 0.5 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 20.7 |

| Population Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (2 yr+) | Young Children (2–3 yrs) | Young Men (19–30 yrs) | Young Women (19–30 yrs) | Older Adults (71+ yrs) | |

| Energy | 0.4 | −2.3 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Protein | −3.5 | −8.1 | −2.6 | −3.6 | −4.5 |

| Total fat | 2.3 | −1.5 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| Saturated fat | −4.3 | −19.5 | −4.6 | −2.6 | −3.8 |

| Monounsaturated fat | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 2.7 |

| n-3 long-chain fatty acids | −7.9 | −13.5 | −6.5 | −10.5 | −7.1 |

| Vitamin A (ret. equiv) | −1.4 | −7.0 | −2.9 | −0.8 | 0.0 |

| Riboflavin | −6.8 | −9.8 | −6.8 | −5.5 | −6.5 |

| Niacin (der. equiv) | −7.7 | −12.7 | −5.4 | −9.7 | −8.9 |

| Vitamin B6 | −3.5 | 6.7 | −3.7 | −5.1 | −1.0 |

| Vitamin B12 | −19.0 | −31.3 | −16.4 | −16.5 | −19.7 |

| Calcium | −1.9 | −5.0 | −1.9 | −0.6 | −2.4 |

| Iodine | −14.1 | −36.4 | −13.0 | −11.9 | −15.4 |

| Iron | 15.2 | 20.9 | 12.6 | 16.7 | 16.2 |

| Magnesium | 5.3 | 10.3 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.5 |

| Phosphorus | −6.2 | −14.1 | −5.2 | −6.0 | −7.2 |

| Potassium | −1.8 | −5.1 | −1.6 | −1.9 | −2.4 |

| Selenium | −3.1 | −6.8 | −2.3 | −4.4 | −3.6 |

| Sodium | 7.3 | 9.5 | 6.1 | 8.1 | 9.0 |

| Zinc | −7.0 | −11.0 | −6.1 | −5.1 | −8.3 |

| Predicted Change with the Combined Accelerated Meat and Milk Scenario | Previously Published Estimations of Nutrient Intake Inadequacy in the Australian Population ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less Than 2% | 2 to <10% | 10 to 20% | Over 20% | |

| Over 20% increase in intake | Iron (YC) | |||

| 10 to 20% increase in intake | Magnesium (YC) | Iron (YM, OA) | Iron (All) | Iron (YW) |

| 2 to <10% increase in intake | Vitamin B6 (YC) | Magnesium (All, YA, OA) | ||

| Less than 2% change in intake | Vitamin A (All, YW, OA) | Vitamin B6 (OA) Calcium (All, YM, YW) | ||

| 2 to <10% decrease in intake | Riboflavin (YC) Niacin (All, YM, YW, OA) Phosphorus (All M, YM, YW, OA) Protein (All, 2–3, YM, YW) Vitamin A (YC) Calcium (YC) Selenium (YC, YM) | Riboflavin (All M, All F, YM, YW) Phosphorus (All F) Protein (OW) Vitamin B6 (All, YM) Selenium (All, YW) | Protein (OM) Zinc (All F, YW, OW) Selenium (OA) | n-3 long-chain fatty acids (YA, OA) Riboflavin (OA) Zinc (All M, YM, OM) Vitamin A (YM) Vitamin B6 (YW) Calcium (OA) |

| 10–20% decrease in intake | Niacin (YC) Vitamin B12 (All M, YM, OM) Iodine (All M, YM) Phosphorus (YC) Zinc (YC) | Vitamin B12 (All F, YW, OW) Iodine (All F, OA) | Iodine (YW) | |

| Over 20% decrease in intake | Vitamin B12 (YC) Iodine (YC) | |||

| Population Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (2 Years+) | Young Children (2–3 Years) | Young Men (19–30 Years) | Young Women (19–30 Years) | Older Adults (71+ Years) | |

| Energy | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Protein | −1.0 | −0.7 | −0.7 | −1.3 | −1.2 |

| Total fat | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 3.0 |

| Saturated fat | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Monounsaturated fat | 0.3 | −0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| n-3 long-chain fatty acids | −7.1 | −8.5 | −5.7 | −9.5 | −6.5 |

| Vitamin A (ret. equiv) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Riboflavin | −1.7 | −1.2 | −1.1 | −1.9 | −1.9 |

| Niacin (der. equiv) | −5.7 | −7.1 | −4.0 | −7.9 | −6.3 |

| Vitamin B6 | −3.6 | −4.7 | −2.3 | −4.8 | −4.4 |

| Vitamin B12 | −7.4 | −6.9 | −5.6 | −6.5 | −8.1 |

| Calcium | 3.5 | 2.4 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 4.1 |

| Iodine | 3.3 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 |

| Iron | 11.8 | 11.6 | 9.5 | 13.7 | 12.6 |

| Magnesium | 3.2 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| Phosphorus | −0.9 | −0.8 | −0.8 | −1.1 | −0.9 |

| Potassium | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| Selenium | −2.4 | −3.6 | −1.8 | −3.8 | −2.8 |

| Sodium | 6.4 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 7.3 | 7.9 |

| Zinc | −3.9 | −2.5 | −3.6 | −2.2 | −4.6 |

| Population Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (2 Years+) | Young Children (2–3 Years) | Young Men (19–30 Years) | Young Women (19–30 Years) | Older Adults (71+ Years) | |

| Energy | −0.8 | −3.3 | −0.8 | −0.7 | −0.7 |

| Protein | −2.6 | −7.4 | −1.9 | −2.3 | −3.2 |

| Total fat | −0.1 | −3.3 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.7 |

| Saturated fat | −6.5 | −20.7 | −6.3 | −5.5 | −6.4 |

| Monounsaturated fat | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 2.3 |

| n-3 long-chain fatty acids | −0.8 | −5.0 | −0.8 | −0.9 | −0.6 |

| Vitamin A (ret. equiv) | −1.7 | −7.2 | −3.2 | −1.1 | −0.2 |

| Riboflavin | −5.1 | −8.7 | −5.7 | −3.6 | −4.7 |

| Niacin (der. equiv) | −2.0 | −5.6 | −1.4 | −1.8 | −2.5 |

| Vitamin B6 | 0.1 | 11.4 | −1.4 | −0.3 | 3.4 |

| Vitamin B12 | −11.7 | −24.3 | −10.8 | −10.0 | −11.6 |

| Calcium | −5.4 | −7.4 | −4.9 | −4.2 | −6.5 |

| Iodine | −17.4 | −38.9 | −15.7 | −15.6 | −19.1 |

| Iron | 3.4 | 9.2 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

| Magnesium | 2.1 | 7.0 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Phosphorus | −5.2 | −13.2 | −4.4 | −4.8 | −6.3 |

| Potassium | −2.4 | −5.9 | −2.2 | −2.4 | −3.1 |

| Selenium | −0.7 | −3.2 | −0.5 | −0.7 | −0.8 |

| Sodium | 0.9 | 3.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 |

| Zinc | −3.1 | −8.5 | −2.4 | −2.9 | −3.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lawrence, A.S.; Huang, H.; Johnson, B.J.; Wycherley, T.P. Impact of a Switch to Plant-Based Foods That Visually and Functionally Mimic Animal-Source Meat and Dairy Milk for the Australian Population—A Dietary Modelling Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081825

Lawrence AS, Huang H, Johnson BJ, Wycherley TP. Impact of a Switch to Plant-Based Foods That Visually and Functionally Mimic Animal-Source Meat and Dairy Milk for the Australian Population—A Dietary Modelling Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(8):1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081825

Chicago/Turabian StyleLawrence, Anita S., Huiying Huang, Brittany J. Johnson, and Thomas P. Wycherley. 2023. "Impact of a Switch to Plant-Based Foods That Visually and Functionally Mimic Animal-Source Meat and Dairy Milk for the Australian Population—A Dietary Modelling Study" Nutrients 15, no. 8: 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081825

APA StyleLawrence, A. S., Huang, H., Johnson, B. J., & Wycherley, T. P. (2023). Impact of a Switch to Plant-Based Foods That Visually and Functionally Mimic Animal-Source Meat and Dairy Milk for the Australian Population—A Dietary Modelling Study. Nutrients, 15(8), 1825. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081825