The Influence of Serious Games in the Promotion of Healthy Diet and Physical Activity Health: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

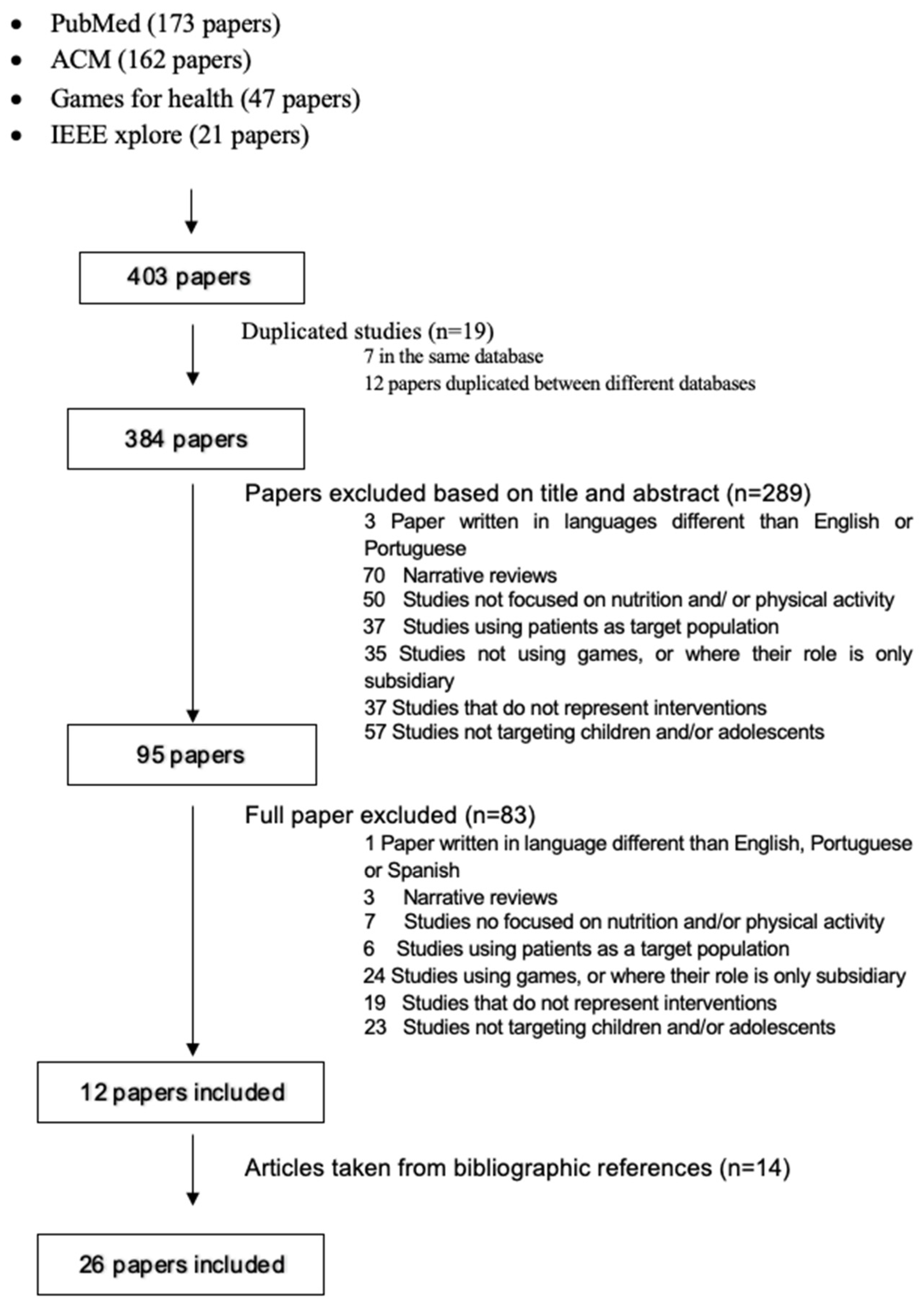

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Intervention Area | Description of the Intervention | Results | Theory Behind the Game | Performative Aspects | Acknowledgment of the Environment | Formative Evaluation or Tailoring | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample/Type of the Study | Duration and Intensity | Assessment Tools | Control | Application Domain | Interactional Elements | Contract with Real Foods | ||||||

| Vepsäläinen et al., 2022. (Finland) [47] Mole’s Veggie Adventures app: a Mobile App to Increase Fruit and Vegetable Acceptance | N | 3–6 y n = 221 Experimental | 3–10 players; 4 sessions of which includes 6 FV each | Background questionnaire to parents (T0). Acceptability to try the FV presented during the game (questionnaire to parents) (T1) | CG had no play sessions with Mole’s Veggie Adventures app | Compared with the CG, the participants in the intervention arm had higher FV acceptance scores at follow-up 3–4 weeks after baseline. | No specific theory. | Cog | Mobile phone | No | No | No |

| Vlieger at al., 2022 (Australia) [45] VitaVillage: improving child nutrition knowledge | N | 9–12 y n = 189 Experimental | 2 sessions (~20 min) | Nutrition knowledge questionnaire (T0, T1) | CG played mathematics games | Compared to the control group, the intervention group’s overall nutrition knowledge was found to increase after playing Vita Village. | No specific theory. | Cog | Tablet | No | No | No |

| Wengreen et al., 2021 (USA) [44] FIT Game’s: Increase Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. | N | 5–11 y n = 978 Experimental | 32 episodes presented; 3 min each episode looped continuously throughout the lunch time | Daily FV consumption of all the children eating school-prepared lunch was estimated using a waste-based measure: before/after lunch-tray photos were taken and height (T0, T1, T2)—BMI and skin-carotenoid concentrations (T0, T1, T2) | CG had no play session with FIT Game | During the intervention phase, children attending the FIT Game schools consumed significantly more consumption FV compared to the baseline. This increase in at-school consumption was reflected in their skin carotenoid concentrations, which was also significantly different between the IG and CG. | No specific theory. | Cog | Television | Yes (game involves eating FV) | No | No |

| Frome et al., 2020 (Canada) [46] Foodbot Factory: a Mobile Serious Game to Increasing Nutrition Knowledge in Children | N | 8–10 y n = 73 Experimental | 10–15 min each day over a five-day period | Nutrition knowledge questionnaire (T0, T1). Nutrition knowledge for each of the four sub-scores measured with the validated Nutrition Attitudes and Knowledge (NAK) Questionnaire. BMI calculated based on parent-reported weight and height (T0) | CG played a control app called “My Salad Shop Bar” | Compared to the control group, children who used Foodbot Factory had significant increases in overall nutrition knowledge, and in Vegetables and Fruits, Protein Foods, and Whole Grain Foods sub-scores. No significant difference in knowledge was observed in the Drinks sub-score | No specific theory. | Cog | Android Tablet | No | No | No |

| Mack et al., 2020 (Germany) [42] Kids Obesity Prevention program (KOP): serious game for children with knowledge-based activities addressing the areas of nutrition, physical activity, and stress coping | N PA | 9–12 y n = 82 Experimental | The IG played the game twice, over a 2-week period, with a different selection of game modules (45 min./session). | Knowledge questionnaire (T0, T1, T2). Changes in dietary behavior, Physical activity and Media consumption questionnaires (T0 + T2; child and parents reports) Acceptance of the game and Emotions during game play questionnaires (T1; child self-reports). Analysis of game data (Int) T2= 2 weeks after play | CG received a brochure with basic information about a healthy lifestyle—“How to make food fun” (food pyramid and PA). | Total knowledge increased with the game and remained at the 2-week follow-up. No positive changes were observed in PA. | No specific theory. Game extensively targets the Dietary Energy Density Principle (DED-P). | Cog Mot | Motion control interface (for moving the avatar in the game) + Tablet (choice selection) | No | No | No |

| Espinosa-Curiel et al., 2020a (Mexico) [57] FoodRateMaster: teaches the characteristics of healthy/unhealthy foods, bearing in mind children’s environment. | N PA | 8–10 y n = 60 Quasi-experimental | 12 game sessions of at least 15 min each, during 6 weeks (45 days) | Food knowledge and Food frequency questionnaires (T0, T1). Parent perception questionnaire (T1) | No control | Increased nutritional knowledge after gameplay. Increased frequency intake of two healthy foods, and decreased intake of 10 unhealthy foods. Positive influence in children’s attitudes (parent reported). | Game is grounded on the constructs of Behavioral Theory, Cognitive Theory and Social Cognitive Theory. | Cog Mot | Microsoft Kinect V2 sensor (basic physical movements in avoiding obstacles and for classifying food) + PC | Yes (6 levels that replicate real food establishments (e.g., a food truck, a restaurant, or a grocery store)) | No | Interdisciplinary team and iterative methodology (user-centered design). |

| Espinosa-Curiel et al., 2020b (Mexico) [48] FoodRateMaster: | EGameFlow and GUESS questionnaires (T1) | Enjoyment and user experience satisfaction with the game were positively correlated and significant predictors of learning. | ||||||||||

| Holzmann et al., 2019 (Germany) [37] Fit, Food, Fun (FFF): a serious game with European country-specific food items, to increase food knowledge and PA | N PA | 12–14 y n = 83 Quasi-experimental | IG played the FFF game individually for 3 consecutive days, 15 min/session. | Dietary behavior, physical activity, and healthy eating attitudes accessed by questionnaire (T0). Nutritional knowledge questionnaire (T0, T1) | CG received a teaching intervention, performed in a classic lecture format (with similar content). | Total knowledge increased in both groups, especially in the CG. | Game of the NUDGE platform. Influenced by the concept of serious gaming, the theory of persuasive gaming, and the concept of positive gaming. | Cog | Tablet | No | No | Pre-game design survey, conducted with 300 adolescents. On preferences, motives, and needs regarding nutritional information and digital gameplay. Usability tests and focus groups. |

| Baranowski et al., 2019b (USA) [49] Escape from Diab and Nanoswarm: Invasion from Inner Space: 2 video games designed to lower risks of type 2 diabetes and obesity by changing youth diet and physical activity behaviors. | N PA | 10–12 y n = 145 (Children in the 85th—99th %ile of BMI) Experimental | Each game had 9 sessions (each episode/session lasting 60 min). Treatment group played Diab and Nano in sequence (total of 2 to 3 months) | BMI assessment; parent self-reported data (T0). Fasting insulin assessment; 32-item Fruits and Vegetables Food Frequency Questionnaire (FV-FFQ); 22- item sweetened beverage FFQ (T0, T1). PA assessed using accelerometer (≤7 days). Gameplay data collected over the Internet (Int) T2 = 2 months after play | CG was a wait list group that received the intervention at the end of the 5-month postbaseline assessment. | No significant differences were detected in any of the tested outcome variables. | Several theories, including Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Determination Theory, Behavioral Inoculation and Transportation Theories and the Elaboration Likelihood Model. | Cog | Computer | No | Yes (barriers to attain diet and physical activity goals were included in “Escape from Diab”) | Quantitative and qualitative methods applied to examine child preferences for storyline genres and plot content of nonviolent video games; also, computer access, knowledge, and game-play frequency. Tailoring: goal-settings were selected according to the player’s behaviors and preferences reported at the baseline. |

| Baranowski et al., 2011 (USA) [58] Escape from Diab and Nanoswarm: Invasion from Inner Space | 10–12 y n = 145 (Children in the 85th—99th %ile of BMI) | 3 nonconsecutive days of 24 h dietary recalls. 5 consecutive days of physical activity using accelerometers. Self-reported height, weight, waist circumference and triceps skinfold assessments (T0, P1, P2, P3). P1 = immediately after Diab P2 = immediately after Nano P3 = 2 months after intervention. | CG received 2 kits (booklet+ CD), comprising a knowledge-based nutrition game and 8 sessions of web-based online games (related to diet, PA and obesity), with questions after each session. | Significant increase in FV intake, in the IG when compared with the CG, including 5 months later. No positive changes in water intake, physical activity, or body composition. | ||||||||

| Experimental | ||||||||||||

| Hermans et al., 2018 (Nederlands) [59] Alien Health Game (AHG): videogame designed to teach elementary school children about nutrition and healthy food choices, while engaging in short cardio exercises. (Dutch version) | N PA | 10–13 y n = 108 Experimental | 30-min long-play sessions, on 2 consecutive days at children’s school. | BMI assessment (T0) Nutrition Knowledge questionnaire (T0, T1, T2) Food-taste test (T1, T2) T2 = 2-week after play. | CG played a web-based nutrition game for the same period of time (Super Shopper). | No substantial differences between IG and CG. IG revealed better knowledge only shortly after playing the game (vs. CG). No evidence for behavior change. | “Mixed reality” platform (AHG uses both digital components as well as tangible, physical components). Theoretically grounded in Situated and Embodied Cognition, including Gestural congruency, and also Behavior Change procedures from Michie inventory. | Cog Mot | SMALLab (mixed-reality educational platform, that uses motion-tracking cameras mounted in a ceiling or on a trussing system, and trackable wands) + interactive whiteboard. | No | No | No |

| Johnson-Glenberg et al., 2014 [40] (USA) | 10–13 y n = 20 | 50 min of play and play-observing (9 min of actual play/dyad). | Nutrition Knowledge questionnaire (T0, T1) | CG: the same performative food choices at the interactive whiteboard, without a game narrative or cardio exercises. | Total knowledge increased in both groups after intervention, but IG outperformed the CG (especially in the follow-up). | |||||||

| Alien Health Game (AHG) | Experimental | |||||||||||

| Johnson-Glenberg et al., 2013 (USA) [60] Alien Health Game (AHG) | 9- 10 y n = 19 Quase-experimental | 45 min of play and play-observing | No Control | Knowledge regarding food choices increased significantly. Evidence of knowledge transfer of general nutrition principles. | ||||||||

| Thompson et al., 2017 (USA) [55] Squire’s Quest! II (SQ2): 10-episode online serious videogame promoting FV intake to preadolescent children, by testing the effect of implementation intentions on FV goal attainment and consumption. | N | 9–11 y n = 400 parent/child dyads Experimental Four groups: Action; Coping; Action+ Coping; Control. Action plans state “how” a goal will be achieved. Coping plans identify a potential barrier and corresponding solution. | 10-episode, online videogame; each session/episode lasting about 25 min; up to three months to play all 10 episodes. | Telephone interviews with children (T1). Game-play data (INT) | Control condition did not create implementation intentions. Parents were involved through newsletters and a dedicated website. | Overall, mean goal attainment was high (FV consumption goals and recipe goals), with no statistically significant differences between groups. Children were more likely to select the F recipe. Program satisfaction was high. | SQ2 is theoretically grounded in SCT, SDT, Behavioral Inoculation Theory, Maintenance Theory and Elaboration Likelihood Model. | Cog | Computer | Yes (brief demonstration videoclips taught players how to make simple FV recipes (‘Virtual Kitchen’)Players set goals to make a recipe at home) | Yes (children selected barrier-specific solutions to potential obstacles to FV intake) | Extensive formative work conducted to ensure children understood the behavioral procedures and could complete them, and also that the game was appealing (e.g., interviews, alpha testing, beta testing). Recipes tested to ensure they were child-friendly, tasted good, and looked attractive. Pilot study to test procedures (enrollment, data collection, intervention delivery) and as final beta test of the online game. |

| DeSmet et al., 2017 (USA) [61] Squire’s Quest! II (SQ2) | Asking behavior and home FV availability questionnaires, (child-reported and parent-reported, respectively) (T0, T1, T2). T2 = 3 months after play. | Despite increasing (and decreasing, at follow-up), children asking behaviors did not lead to an increase in FV at home or to more FV consumption. | ||||||||||

| Cullen et al., 2016 (USA) [62] Squire’s Quest! II (SQ2) | 24 h dietary recalls conducted via phone (3 unannounced 24 h dietary recalls, FV intake averaged) (T0, T2). T2 = 3 months after play. | Action and coping groups participants reported higher V intake at dinner. Significant increases over time of F intake at breakfast, lunch, and snack (at follow-up). | ||||||||||

| Thompson et al., 2015 (USA) [63] Squire’s Quest! II (SQ2) | 9–11 y n = 387 parent/child dyads Experimental (Four groups) | 24 h dietary recalls conducted via phone (3 unannounced 24 h dietary recalls, food and beverage intake averaged) (T0, T1, T2). Demographic data (T0) T2 = 3 months after play. | Children who only created action plans showed increased intake of FVs at follow-up, and favorable changes in energy density and key nutrients. F intake increased over time, regardless individual IG results. | |||||||||

| Sharma et al., 2015 (USA) [51] Quest to Lava Mountain (QTLM): an action-adventure game that requires children to make simulated appropriate food choices and stay physically active to move steadily through the game and succeed. | N PA | 9–11 y n = 94 Quase-experimental | 90 min/week for 6 weeks recommended | Demographic data (T0). Two random 24 h dietary recall interviews. Child self-report surveys to assess Diet and Physical Activity Habits and Related Psychosocial Mediators; anthropometric measures (T0, T1) QTLM usability, exposure to, and progress achieved (INT) | CG were children in three comparison schools (wait list to play QTLM) | Children in IG reported decreased sugar consumption and higher N/PA attitudes pre- to post intervention. No significant effects on PA. | Social Cognitive Theory and the Theory of Reasoned Action | Cog | Computer | No | No | No |

| Marchetti et al., 2015 (Italy) [64] Gustavo in Gnam’s Planet: a game to improve knowledge on healthy foods and increase their consumption. | N | 14–18 y n = 83 Qusai-experimental | 30 min–2 h/day, during one week. | Healthy food knowledge questionnaire, Food frequency questionnaire, and Interest questionnaire (T0, T1) | No control | Knowledge on healthy diet improved with the game. Increased consumption of different healthy foods and lower consumption of sugary snacks post-play. | Theoretically grounded in the Transtheoretical Model of Change, the SCT, the SDT, and the Elaboration Likelihood Model. | Cog | Computer | No | No | No |

| Saksono et al., 2015 (USA) [39] Spaceship Launch (SL): game with Fitbit activity trackers, to increase parent and child PA. | PA | 3–8 y n = 14 (and 15 caregivers) Quase-experimental | ≥once a week total of 3 weeks | Demographics, PA intention and parental PA modeling and support (T0). PA intention survey. Experience with the game and impact in intentions and modeling behavior (semi-structured interviews with parents) (T1). | No control | Children and parents reported an increase in the intention to be physically more active. | Informed by SCT, SDT, and concepts of Parental PA modeling (as predictor of children’s PA) and collaborative games in family | Mot | Fitbit activity trackers + Web app (home devices and large interactive display in gym sessions). | No | No | Formative and post-gameplay studies, to guide the game design. Focus groups with parents to probe parental attitudes towards, and support for, their child’s PA. |

| Majumdar et al., 2013 (USA) [50] Creature-101: online game to promote energy balance-related behaviors (EBRBs) | N PA | 11–13 y n = 590 Quasi-experimental | 7 sessions, 30 min each, for 1 month | Frequency and amount of the targeted behaviors (Eat-Move instrument) and demographic data (T0, T1) | CG played 8 minigames (Whyville). matching standard science/health curriculums of NYC. Nutrition games excluded and networking activities deactivated. | Decrease in the consumption of SB and PS. No significant positive effects in FV and water intake, PA, or screen time. | Based on SCT and SDT. Behavioral change procedures based on Michie inventory. Embedded in a social networking structure (Elgg). | Cog | PC (game experience mostly through a MMO virtual world (Tween) | No | No | Focus groups and in-class observations to obtain feed-back about game structure and if it met behavior change objectives (link of the game to real-life behaviors). Beta-testing. |

| Macvean et al., 2012 (UK) [43] iFitQuest: Location-aware mobile exergame, played on the iPhone, by using Google Maps. The game is made up of a number of “mini-games”, each designed to target a different type of fitness. | PA | 12–15 y n = 25 Experimental | 3 h session, with 30 min of play (15-min/mini game) | Background questionnaire (T0). Exertion and enjoyment of exercise with the game assessed through questionnaire; interview of expert PA teacher (that observed sessions) (T1). In-game log-files and rating collected during play (INT) | No control | IG achieved levels of speed representing “moderate to vigorous” activity, while playing iFitQuest. | No specific theory. Being physically demanding, iFitQuest grounds itself in published exergames design requirements to maintain motivation and enjoyment. | Mot | iPhone (exercise of game-players in real world physical movements are used to control the virtual character). | No | No | Preliminary school-based field study to guide the game development |

| Amaro et al., 2006 (Italy) [4] Kalédo: a board-game to teach nutrition knowledge and to influence dietary behavior, regarding Mediterranean diet. | N PA | 11–14 y n = 241 Experimental | 2 to 4 players; 24 play sessions (15–30-min-long play sessions, once a week) | Nutrition knowledge, dietary intake, and physical activity questionnaires (T0, T1). BMI measurement (T0) | CG had no play sessions with Kalèdo. | Significant increase in nutrition knowledge and in weekly vegetable intake (vs. CG). | Unspecified. Combined purpose of promoting/discouraging specific dietary behaviors. | Cog | Board Game (cards, paws, play pieces, dice, “kaleidoscopes”) | No | No | No |

| Cullen et al., 2005 (USA) [65] Squire’s Quest! I: a 10-session interactive game to enable children to increase FJV intake, through activities promoting increasing asking behaviors and increasing skills in FJV preparation through virtual recipes. | N | 8–12 y n = 1578 Experimental | 25 min/session, in a total of 10 sessions/episodes, for 5 weeks. | 4 days of dietary intake assessment using FIRSSt, (T0, T1). Demographic data (T0). | GC without intervention | IG increased the consumption of fruit and 100% juice at snacks and the consumption of regular vegetables at lunch. | Based on social cognitive theory, the game used multiple exposure and fun in educational activities to increase preferences for and FJV consumption. | Cog | Computer | Yes (game involves students preparing FJV recipes in a virtual kitchen, and then setting goals to make recipes at home). | Yes (game involves a problem-solving routine to help players think of practices to increase the likelihood of eating more FJV). | Focus group discussions with fourth-grade children to assess interest in the story line and to identify child-desired characters’ characteristics. Tailoring: FJV were selected based on the child’s food preferences reported at baseline. |

| Baranowski et al., 2003 (USA) [66] Squire’s Quest! I | IG increased their FJV consumption by 1.0 servings more than the CG. | |||||||||||

References

- Morales Camacho, W.J.; Molina Díaz, J.M.; Plata Ortiz, S.; Plata Ortiz, J.E.; Morales Camacho, M.A.; Calderón, B.P. Childhood obesity: Aetiology, comorbidities, and treatment. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2019, 35, e3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.L. A Review of the Prevention and Medical Management of Childhood Obesity. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, H.; Suneja, U. Pediatric Obesity Nutritional Guidelines; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Moore, T.H.; Hooper, L.; Gao, Y.; Zayegh, A.; Ijaz, S.; Elwenspoek, M.; Foxen, S.C.; Magee, L.; O’Malley, C.; et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 7, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Qi, X.; Locke, J.; Rehman, S. Childhood and Adolescent Obesity in the United States: A Public Health Concern. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2019, 6, 2333794X19891305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weihrauch-Blüher, S.; Schwarz, P.; Klusmann, J.H. Childhood obesity: Increased risk for cardiometabolic disease and cancer in adulthood. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2019, 92, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanigan, J. Prevention of overweight and obesity in early life. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Qi, S.J. Childhood obesity and food intake. World J. Pediatr. WJP 2015, 11, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosiek, A.; Maciejewska, N.F.; Leksowski, K.; Rosiek-Kryszewska, A.; Leksowski, Ł. Effect of Television on Obesity and Excess of Weight and Consequences of Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 9408–9426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanelli, R.; Cecchi, N.; Carbone, M.G.; Dinardo, M.; Gaudino, G.; Del Giudice, E.M.; Umano, G.R. Pediatric obesity: Prevention is better than care. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseng, F.; Hygen, B.W.; Wichstrøm, L. Time spent gaming and psychiatric symptoms in childhood: Cross-sectional associations and longitudinal effects. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESA. 2021 Sales, Demographic, and Usage Data: Essential Facts about the Video Game Industry. Entertainment Software Association. Available online: http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/2021-Essential-Facts-About-the-Video-Game-Industry-1.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Thompson, D. Designing serious video games for health behavior change: Current status and future directions. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 807–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, P.; Moreira, P.M.; Reis, L.P. Serious games for rehabilitation: A survey and a classification towards a taxonomy. In Proceedings of the 5th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 16–19 June 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, P.M.; Cole, S.W.; Bradlyn, A.S.; Pollock, B.H. A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 2008, 122, e305–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSmet, A.; Van Ryckeghem, D.; Compernolle, S.; Baranowski, T.; Thompson, D.; Crombez, G.; Poels, K.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Bastiaensens, S.; Van Cleemput, K.; et al. A meta-analysis of serious digital games for healthy lifestyle promotion. Prev. Med. 2014, 69, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattanasoontorn, V.; Boada, I.; García, R.; Sbert, M. Serious games for health. Entertain. Comput. 2013, 4, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, T.; Buday, R.; Thompson, D.I.; Baranowski, J. Playing for real: Video games and stories for health-related behavior change. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, I.; Bayer, C.; Schäffeler, N.; Reiband, N.; Brölz, E.; Zurstiege, G.; Fernandez-Aranda, F.; Gawrilow, C.; Zipfel, S. Chances and Limitations of Video Games in the Fight against Childhood Obesity-A Systematic Review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2017, 25, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, T.; Ryan, C.; Hoyos-Cespedes, A.; Lu, A.S. Nutrition education and dietary behavior change games: A scoping review. Games Health J. 2019, 8, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.Y.; Riantiningtyas, R.R.; Kanstrup, M.B.; Papavasileiou, M.; Liem, G.D.; Olsen, A. Can games change children’s eating behaviour? A review of gamification and serious games. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, S.; Ratzki-Leewing, A.; Gwadry-Sridhar, F. Moving beyond the stigma: Systematic review of video games and their potential to combat obesity. Int. J. Hypertens. 2011, 2011, 179124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadomura, A.; Tsukada, K.; Siio, I. EducaTableware: Sound Emitting Tableware for Encouraging Dietary Education. J. Inf. Process. 2014, 22, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, S.; Tuorila, H. Sensory education decreases food neophobia score and encourages trying unfamiliar foods in 8–12-year-old children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, T.M.; Staples, P.A.; Gibson, E.L.; Halford, J.C. Food neophobia and ’picky/fussy’ eating in children: A review. Appetite 2008, 50, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. (Eds.) Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983, 51, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. Resistance to persuasion conferred by active and passive prior refutation of the same and alternative counterarguments. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1961, 63, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.J. Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M. A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. Neb. Symp. Motiv. 1980, 27, 65–116. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.C.; Brock, T.C. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M. From Theory to Intervention: Mapping Theoretically Derived Behavioural Determinants to Behaviour Change Techniques. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, S.L.; Schäfer, H.; Groh, G.; Plecher, D.A.; Klinker, G.; Schauberger, G.; Hauner, H.; Holzapfel, C. Short-Term Effects of the Serious Game “Fit, Food, Fun” on Nutritional Knowledge: A Pilot Study among Children and Adolescents. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, H.; Plecher, D.A.; Holzmann, S.L.; Groh, G.; Klinker, G.; Holzapfel, C.; Hauner, H. NUDGE-NUtritional, Digital Games in Enable. In Positive Gaming: Workshop on Gamification and Games for Wellbeing, at CHI PLAY ’17; University of Waterloo Library: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017; pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Saksono, H.; Ranade, A.; Kamarthi, G.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C.; Hoffman, J.A.; Wirth, C.; Parker, A.G. Spaceship Launch: Designing a Collaborative Exergame for Families. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (CSCW ’15), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M.C.; Savio-Ramos, C.; Henry, H. “Alien Health”: A Nutrition Instruction Exergame Using the Kinect Sensor. Games Health J. 2014, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro, S.; Viggiano, A.; Di Costanzo, A.; Madeo, I.; Viggiano, A.; Baccari, M.E.; Marchitelli, E.; Raia, M.; Viggiano, E.; Deepak, S.; et al. Kalèdo, a new educational board-game, gives nutritional rudiments and encourages healthy eating in children: A pilot cluster randomized trial. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2006, 165, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, I.; Reiband, N.; Etges, C.; Eichhorn, S.; Schaeffeler, N.; Zurstiege, G.; Gawrilow, C.; Weimer, K.; Peeraully, R.; Teufel, M.; et al. The Kids Obesity Prevention Program: Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate a Serious Game for the Prevention and Treatment of Childhood Obesity. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macvean, A.; Robertson, J. FitQuest: A school based study of a mobile location-aware exergame for adolescents. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services (MobileHCI’12), San Francisco, CA, USA, 21–25 September 2012; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wengreen, H.J.; Joyner, D.; Kimball, S.S.; Schwartz, S.; Madden, G.J. A Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the FIT Game’s Efficacy in Increasing Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vlieger, N.M.; Sainsbury, L.; Smith, S.P.; Riley, N.; Miller, A.; Collins, C.E.; Bucher, T. Feasibility and Acceptability of ‘VitaVillage’: A Serious Game for Nutrition Education. Nutrients 2021, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froome, H.M.; Townson, C.; Rhodes, S.; Franco-Arellano, B.; LeSage, A.; Savaglio, R.; Brown, J.M.; Hughes, J.; Kapralos, B.; Arcand, J. The Effectiveness of the Foodbot Factory Mobile Serious Game on Increasing Nutrition Knowledge in Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vepsäläinen, H.; Skaffari, E.; Wojtkowska, K.; Barlińska, J.; Kinnunen, S.; Makkonen, R.; Heikkilä, M.; Lehtovirta, M.; Ray, C.; Suhonen, E.; et al. A Mobile App to Increase Fruit and Vegetable Acceptance Among Finnish and Polish Preschoolers: Randomized Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e30352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Curiel, I.E.; Pozas-Bogarin, E.E.; Martínez-Miranda JPérez-Espinosa, H. Relationship Between Children’s Enjoyment, User Experience Satisfaction, and Learning in a Serious Video Game for Nutrition Education: Empirical Pilot Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e21813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, T.; Baranowski, J.; Chen, T.A.; Buday, R.; Beltran, A.; Dadabhoy, H.; Ryan, C.; Lu, A.S. Videogames That Encourage Healthy Behavior Did Not Alter Fasting Insulin or Other Diabetes Risks in Children: Randomized Clinical Trial. Games Health J. 2019, 8, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, D.; Koch, P.A.; Lee, H.; Contento, I.R.; Islas-Ramos, A.D.; Fu, D. “Creature-101”: A Serious Game to Promote Energy Balance-Related Behaviors Among Middle School Adolescents. Games Health J. 2013, 2, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Shegog, R.; Chow, J.; Finley, C.; Pomeroy, M.; Smith, C.; Hoelscher, D.M. Effects of the Quest to Lava Mountain Computer Game on Dietary and Physical Activity Behaviors of Elementary School Children: A Pilot Group-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greszczuk, C. Making Messages Work. The Health Foundation, 21 April 2020. Available online: https://www.health.org.uk/thinking-differently-about-health/making-messages-work (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Parisod, H.; Pakarinen, A.; Kauhanen, L.; Aromaa, M.; Leppänen, V.; Liukkonen, T.N.; Smed, J.; Salanterä, S. Promoting Children’s Health with Digital Games: A Review of Reviews. Games Health J. 2014, 3, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D. Incorporating Behavioral Techniques into a Serious Videogame for Children. Games Health J. 2017, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FatWorld: A Game about the Politics of Nutrition. Persuasive Games. Available online: http://persuasivegames.com/game/fatworld (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Espinosa-Curiel, I.E.; Pozas-Bogarin, E.E.; Lozano-Salas, J.L.; Martínez-Miranda, J.; Delgado-Pérez, E.E.; Estrada-Zamarron, L.S. Nutritional Education and Promotion of Healthy Eating Behaviors Among Mexican Children Through Video Games: Design and Pilot Test of FoodRateMaster. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e16431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowski, T.; Baranowski, J.; Thompson, D.; Buday, R.; Jago, R.; Griffith, M.J.; Islam, N.; Nguyen, N.; Watson, K.B. Video game play, child diet, and physical activity behavior change a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 40, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, R.; van den Broek, N.; Nederkoorn, C.; Otten, R.; Ruiter, E.; Johnson-Glenberg, M.C. Feed the Alien! The Effects of a Nutrition Instruction Game on Children’s Nutritional Knowledge and Food Intake. Games Health J. 2018, 7, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson-Glenberg, M.C.; Hekler, E.B. “Alien Health Game”: An Embodied Exergame to Instruct in Nutrition and MyPlate. Games Health J. 2013, 2, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSmet, A.; Liu, Y.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Baranowski, T.; Thompson, D. The effectiveness of asking behaviors among 9–11 year-old children in increasing home availability and children’s intake of fruit and vegetables: Results from the Squire’s Quest II self-regulation game intervention. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, K.W.; Liu, Y.; Thompson, D.I. Meal-Specific Dietary Changes from Squires Quest! II: A Serious Video Game Intervention. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 326–330.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Bhatt, R.; Vazquez, I.; Cullen, K.W.; Baranowski, J.; Baranowski, T.; Liu, Y. Creating action plans in a serious video game increases and maintains child fruit-vegetable intake: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Fraticelli, F.; Polcini, F.; Lato, R.; Pintaudi, B.; Nicolucci, A.; Fulcheri, M.; Mohn, A.; Chiarelli, F.; Di Vieste, G.; et al. Preventing Adolescents’ Diabesity: Design, Development, and First Evaluation of “Gustavo in Gnam’s Planet”. Games Health J. 2015, 4, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, K.W.; Watson, K.; Baranowski, T.; Baranowski, J.H.; Zakeri, I. Squire’s Quest: Intervention changes occurred at lunch and snack meals. Appetite 2005, 45, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, T.; Baranowski, J.; Cullen, K.W.; Marsh, T.; Islam, N.; Zakeri, I.; Honess-Morreale, L.; deMoor, C. Squire’s Quest! Dietary outcome evaluation of a multimedia game. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003, 24, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lamas, S.; Rebelo, S.; da Costa, S.; Sousa, H.; Zagalo, N.; Pinto, E. The Influence of Serious Games in the Promotion of Healthy Diet and Physical Activity Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061399

Lamas S, Rebelo S, da Costa S, Sousa H, Zagalo N, Pinto E. The Influence of Serious Games in the Promotion of Healthy Diet and Physical Activity Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(6):1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061399

Chicago/Turabian StyleLamas, Susana, Sofia Rebelo, Sofia da Costa, Helena Sousa, Nelson Zagalo, and Elisabete Pinto. 2023. "The Influence of Serious Games in the Promotion of Healthy Diet and Physical Activity Health: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 15, no. 6: 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061399

APA StyleLamas, S., Rebelo, S., da Costa, S., Sousa, H., Zagalo, N., & Pinto, E. (2023). The Influence of Serious Games in the Promotion of Healthy Diet and Physical Activity Health: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 15(6), 1399. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061399