IgE-Dependent Allergy in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

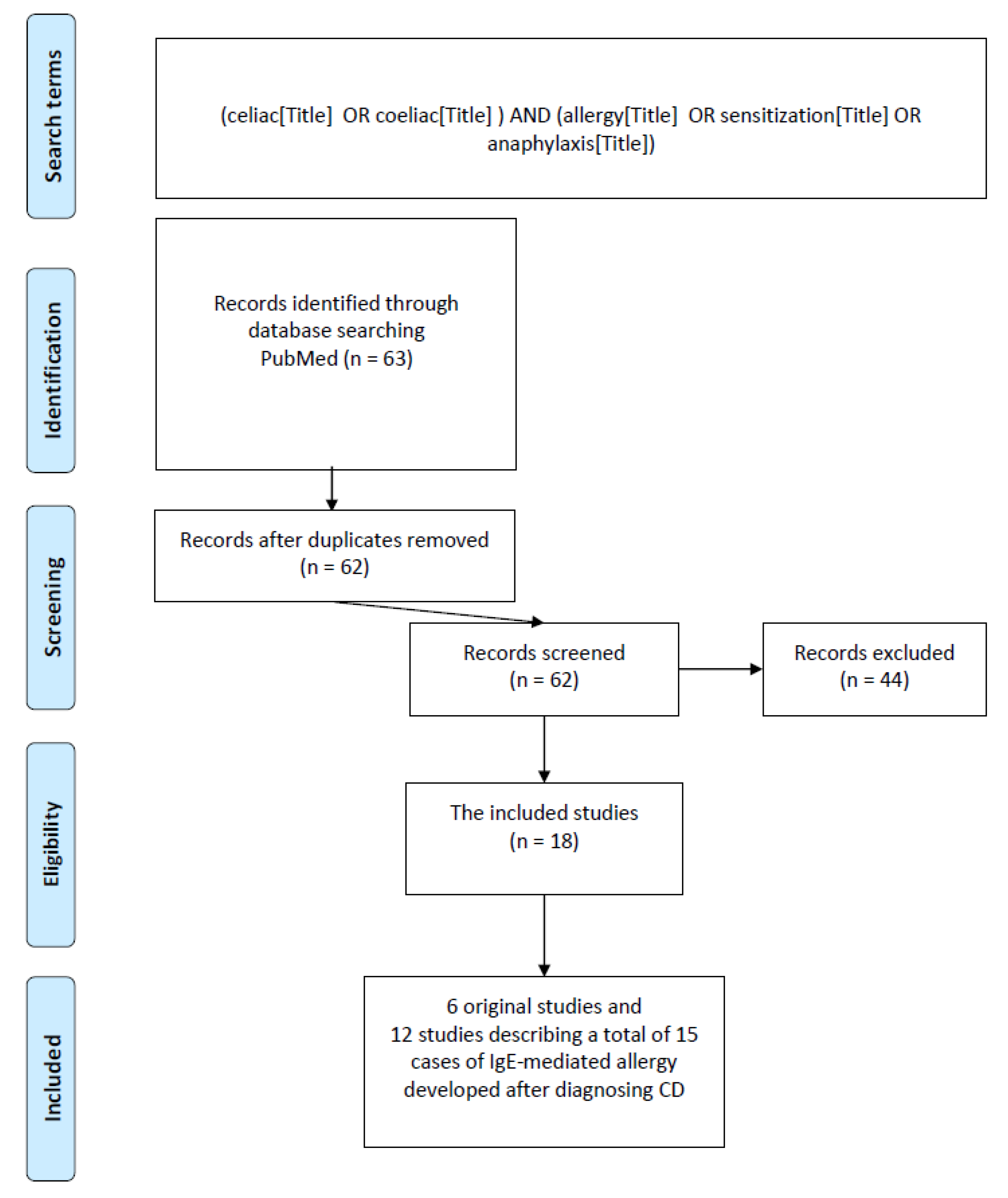

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Incidence of A-IgE/Sensitization in Patients with CD

3.2. Clinical Manifestation of A-IgE in CD Patients

| No. | Autor/Publication Year/n 1 | Age of CD Diagnosis/Gender | Symptoms 2 | Confirmed Allergens | Other Concomitant Allergic Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kuitunen et al. [31]; 1986; n = 1 | 10.9 years/boy | Vomiting; diarrhea | Cow’s milk | |

| 2 | Rotiroti et al. [22]; 2007; n = 1 | 23 years/woman | Generalized urticaria, upper airway angioedema, wheezing, laryngeal edema, vomiting, profound hypotension, and loss of consciousness | Lupines | |

| 3 | Torres et al. [23]; 2008; n = 1 | 4 years/girl | Abdominal pain, gastric fullness, flatulence, and vomiting immediately | Wheat, gliadin, barley, and oat | |

| 4 | Sánchez-García et al. [24]; 2011; n = 1 | 2 years/girl | Abdominal pain, facial urticaria, and generalized urticaria | Cow’s milk; eggs | AD; asthma |

| 5 | Wong et al. [19]; 2014; n = 1 | 18 months/girl | Urticaria, cough, shortness of breath with accidental exposures to wheat, tingly mouth, and wheezing | Wheat | |

| 6 | Heffler et al. [25]; 2014; n = 1 | 37 years/woman | Chronic urticaria | Buckwheat flour | |

| 7 | Dondi et al. [28]; 2015; n = 1 | 9 years/boy | Oral allergy syndrome, respiratory impairment, hives, angioedema, abdominal pain or vomiting, and mild-to-moderate anaphylactic reactions | Cow’s milk | AD, inhalant allergies, and asthma |

| 8 | Martín-Muñoz et al. [20]; 2016; n = 2 | 25 months/boy | Wheezing, urticarial, lip edema, vomiting, and bronchospasm | bdCD: hen’s eggs, lentils, and fish adCD: wheat flour, hake, eggs, and lentils | AD, spring rhinitis, and asthma |

| 14 months/girl | Nasal pruritus, facial angioedema, dyspnea, and cough | Wheat flour | Spring rhinitis | ||

| 9 | Micozzi et al. [30]; 2018; n = 2 | 12 months/nd | Delayed growth, abdominal pain, vomiting, sneezing, and lacrimation | bdCD: hen’s eggs, cow’s milk adCD: wheat flour | Rhinoconjunctivitis; asthma |

| 6 months/nd | Delayed growth; eyelid angioedema | bdCD: hen’s eggs, cow’s milk adCD: wheat flour | Rhinoconjunctivitis; asthma | ||

| 10 | Borghini et al. [29]; 2018; n = 1 | 25 years/woman | Swelling, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss | Wheat | AD; erythematous skin lesions |

| 11 | Mennini et al. [27]; 2019; n = 1 | 3 years/boy | Anaphylaxis | bdCD: hen’s eggs adCD: wheat | AD, rhinitis, and asthma |

| 12 | Lombardi et al. [26]; 2019; n = 2 | 5 years/girl | Generalized urticaria, lip swelling, abdominal, pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and respiratory distress | Wheat | |

| 26 years/woman | Hypotension, generalized urticaria, lip swelling, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and dyspnea | Wheat |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ludvigsson, J.F.; Leffler, D.A.; Bai, J.C.; Biagi, F.; Fasano, A.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Kelly, C.P.; Leonard, J.N.; et al. The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013, 62, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabo, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Hill, I.D.; Kelly, C.P.; Calderwood, A.H.; Murray, J.A.; American College of, G. ACG clinical guidelines: Diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 656–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljada, B.; Zohni, A.; El-Matary, W. The Gluten-Free Diet for Celiac Disease and Beyond. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majsiak, E.; Choina, M.; Gray, A.M.; Wysokiński, M.; Cukrowska, B. Clinical Manifestation and Diagnostic Process of Celiac Disease in Poland—Comparison of Pediatric and Adult Patients in Retrospective Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majsiak, E.; Choina, M.; Golicki, D.; Gray, A.M.; Cukrowska, B. The impact of symptoms on quality of life before and after diagnosis of coeliac disease: The results from a Polish population survey and comparison with the results from the United Kingdom. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokoris, S.; Gavriilaki, E.; Vrigκou, E.; Triantafyllou, K.; Roumelioti, A.; Kyriakou, E.; Lada, E.; Gialeraki, A.; Kalantzis, D.; Grouzi, E. Anemia in Celiac Disease: Multiple Aspects of the Same Coin. Acta Haematol. 2023, 146, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, C.A.; Hellings, P.W.; Agache, I. Global Atlas of Allergic Rhinitis and Chronic Rhinosinusitis; European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, J.; Alsayouri, K.; Sadowski, A. Allergy. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545237/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- Cukrowska, B.; Sowinska, A.; Bierla, J.B.; Czarnowska, E.; Rybak, A.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U. Intestinal epithelium, intraepithelial lymphocytes and the gut microbiota—Key players in the pathogenesis of celiac disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 7505–7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, T.; Meyer, C.; Abadie, V. B lymphocytes contribute to celiac disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2608–2610.e2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudowska, B.; Lebensztejn, D.M. Immunogloboulin E-Mediated Food Sensitization in Children with Celiac Disease: A Single-Center Experience. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2021, 24, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, C.; Cavallaro, R.; Iovino, P.; Sabbatini, F.; Palumbo, A.; Amoruso, D.; Tortora, R.; Mazzacca, G. Allergy prevalence in adult celiac disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 1199–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentia, A.; Arranz, E.; Hernandez, N.; Garrote, A.; Panzani, R.; Blanco, A. Allergy after inhalation and ingestion of cereals involve different allergens in allergic and celiac disease. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2008, 2, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzarin, C.M.V.; Silva, N.O.E.; Venturieri, M.O.; Solé, D.; Oliveira, R.P.; Sdepanian, V.L. Celiac Disease and Sensitization to Wheat, Rye, and Barley: Should We Be Concerned? Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 182, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enroth, S.; Dahlbom, I.; Hansson, T.; Johansson, Å.; Gyllensten, U. Prevalence and sensitization of atopic allergy and coeliac disease in the Northern Sweden Population Health Study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2013, 72, 21403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerl, D.; Bastid, C.; Ramadan, S.; Frossard, J.L.; Caubet, J.C.; Roux-Lombard, P. Identifying True Celiac Disease and Wheat Allergy in the Era of Fashion Driven Gluten-Free Diets. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 179, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Ko, H.H.; Chan, E.S. IgE-Mediated allergy to wheat in a child with celiac disease—A case report. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2014, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Muñoz, M.F.; Rivero, D.; Díaz Perales, A.; Polanco, I.; Quirce, S. Wheat allergy in celiac children. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 27, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, G.; Andreozzi, L.; Cipriani, F.; Giannetti, A.; Gallucci, M.; Caffarelli, C. Wheat Allergy in Children: A Comprehensive Update. Medicina 2019, 55, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotiroti, G.; Skypala, I.; Senna, G.; Passalacqua, G. Anaphylaxis due to lupine flour in a celiac patient. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 17, 204–205. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, J.A.; Sastre, J.; de las Heras, M.; Cuesta, J.; Lombardero, M.; Ledesma, A. IgE-mediated cereal allergy and latent celiac disease. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 18, 412–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García, S.; Ibáñez, M.D.; Martinez-Gómez, M.J.; Escudero, C.; Vereda, A.; Fernández-Rodríguez, M.; Rodríguez del Río, P. Eosinophilic esophagitis, celiac disease, and immunoglobulin E-mediated allergy in a 2-year-old child. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 21, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Heffler, E.; Bruna, E.; Rolla, G. Chronic urticaria in a celiac patient: Role of food allergy. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 24, 356–357. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, C.; Savi, E.; Passalacqua, G. Concomitant Celiac Disease and Wheat Allergy: 2 Case Reports. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2019, 29, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennini, M.; Fiocchi, A.; Trovato, C.M.; Ferrari, F.; Iorfida, D.; Cucchiara, S.; Montuori, M. Anaphylaxis after wheat ingestion in a patient with coeliac disease: Two kinds of reactions and the same culprit food. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 31, 893–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, A.; Ricci, G.; Matricardi, P.M.; Pession, A. Fatal anaphylaxis to wheat after gluten-free diet in an adolescent with celiac disease. Allergol. Int. 2015, 64, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghini, R.; Donato, G.; Marino, M.; Casale, R.; Tola, M.D.; Picarelli, A. In extremis diagnosis of celiac disease and concomitant wheat allergy. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 29, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micozzi, S.; Infante, S.; Fuentes-Aparicio, V.; Álvarez-Perea, A.; Zapatero, L. Celiac Disease and Wheat Allergy: A Growing Association? Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 176, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuitunen, P.; Savilahti, E.; Verkasalo, M. Late mucosal relapse in a boy with coeliac disease and cow’s milk allergy. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 1986, 75, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K.; de las Vecillas, L.; Dramburg, S.; Hilger, C.; Matricardi, P.; Santos, A.F. (Eds.) Molecular Allergology User’s Guide 2.0; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Majsiak, E.; Choina, M.; Miśkiewicz, K.; Doniec, Z.; Kurzawa, R. Oleosins: A Short Allergy Review; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Knyziak-Mędrzycka, I.; Szychta, M.; Majsiak, E.; Fal, A.M.; Doniec, Z.; Cukrowska, B. The Precision Allergy Molecular Diagnosis (PAMD@) in Monitoring the Atopic March in a Child with a Primary Food Allergy: Case Report. J. Asthma Allergy 2022, 15, 1263–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoliński, B.; Choina, M.; Majsiak, E. Korzyści jakie przynosi diagnostyka molekularna w rozpoznawaniu i leczeniu alergii. Alergia 2019, 79, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

| Keywords | All Articles in PubMed Included in the Analysis | Original Studies | Systematic Reviews | Case Studies | Review Articles | Inconsistent with the Search Topic | Other 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “allergy&celiac/coeliac” | 48 1 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 5 | 17 | 13 |

| “sensitization&celiac/coeliac” | 6 (+1 2) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| “anaphylaxis&celiac/coeliac” | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 57 (+1 2) | 6 | 0 | 12 | 5 | 18 | 16 |

| No. | Study | Number of All Patients Tested/Number with CD | Age Cohort (Mean Age, y) | Region/Type of Study/Period | Tests Used for Diagnosis of Allergy/Sensitization | Tested Allergens | The Prevalence of Allergies/Sensitivities in Celiac Disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ciacci et al. [14]; 2004. | 4114/1044 CD | Adults | Italy; prospective; 1992–2002 | Reporting allergy symptoms; sIgE/nd; SPT/Stallergenes Srl, Saronno, Italy | Graminacee, Parietaria officinalis, Dermatophagoides, and Alternaria; skin: nickel, chrome, latex, cosmetics, soaps, and dye; milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, nuts/peanuts, tomato, citrus fruits, and soya; miscellaneous: all the reactions provoked by less common antigens (for example, pigeon’s feathers, cloves, cinnamon, and olive tree pollen) | 16.6% had sIgE for minimum of one tested allergen |

| 2 | Armentia et al. [15]; 2008. | 88/57 CD | Children; adults | Spain; prospective; ND 1 | SPT/ALK-ABELLO Laboratories, Madrid, Spain | Pollen, mites, molds, and different foods; | 7.0% sIgE to wheat, but no patient in this group had IgE to other food allergens |

| sIgE/Pharmacia CAP System FEIA, (Uppsala, Sweden) | wheat, barley, and rye flours and a battery of food allergens: whole milk, α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, casein, eggs (white and yolk), legumes, nuts, and fish; Tri a 14, Tri a aA_TI (inhibitor a1 α-amylase (included CM3)) | ||||||

| 3 | Enroth et al. [17]; 2013. | 1068/24 people with TG2 IgA and/or TG2 IgG | Children (14+); adults | Sweden; prospective; 2006 and 2009 | Self-reported allergy | Grass/pollen, cow’s milk, gluten, fur, fish, dust, cold air, mold, organic solvents, medicines, and others | No people with allergies were found in the study group with CD |

| sIgE/ImmunoCAP®, F×5, and Phadiatop Thermo Fisher Scientific/Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden | ND | ||||||

| 4 | Spoerl [18]; 2019. | 2965/128 subjects with positive tTG IgA | Children; adults | Switzerland; retrospective; 2010–2016 | sIgE/ImmunoCAP® Thermo Fisher Scientific/Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden) | Wheat extract, molecule Tri a 19, and molecular timothy grass Phl p 1, Phl p 5, Phl p 7, and Phl p 12 | Wheat allergy did not seem to be associated with CD |

| 5 | Lanzarin et al. [16]; 2020. | 74/74 CD | 1–20 years of age | Brazil; prospective; NR | sIgE/ImmunoCAP®, Thermo Fisher Scientific/Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden)) | Wheat, rye, barley, and malt | Frequency of sensitization to wheat, rye, barley, and malt among CD patients was 4, 10.8, 5.4, and 2.7%, respectively |

| 6 | Cudowska et al. [12]; 2021. | 59/59 CD | Children (average age 8.1) | Poland; retrospective; 2016–2018 | sIgE/Polycheck; Biocheck GmbH, Münster, Germany | 20 major food and airborne allergens | 20.3% children were sensitized |

| SPT/Allergopharma and Nexter | Milk, eggs, soy, wheat, pork, cod, citrus fruits, peanuts, and airborne allergens |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majsiak, E.; Choina, M.; Knyziak-Mędrzycka, I.; Bierła, J.B.; Janeczek, K.; Wykrota, J.; Cukrowska, B. IgE-Dependent Allergy in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040995

Majsiak E, Choina M, Knyziak-Mędrzycka I, Bierła JB, Janeczek K, Wykrota J, Cukrowska B. IgE-Dependent Allergy in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(4):995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040995

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajsiak, Emilia, Magdalena Choina, Izabela Knyziak-Mędrzycka, Joanna Beata Bierła, Kamil Janeczek, Julia Wykrota, and Bożena Cukrowska. 2023. "IgE-Dependent Allergy in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 15, no. 4: 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040995

APA StyleMajsiak, E., Choina, M., Knyziak-Mędrzycka, I., Bierła, J. B., Janeczek, K., Wykrota, J., & Cukrowska, B. (2023). IgE-Dependent Allergy in Patients with Celiac Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 15(4), 995. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15040995