Yarning about Diet: The Applicability of Dietary Assessment Methods in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Concept

2.2.3. Context

2.3. Types of Studies

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Selection Process

2.6. Data Extraction and Charting

2.7. Critical Apprasial

2.8. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

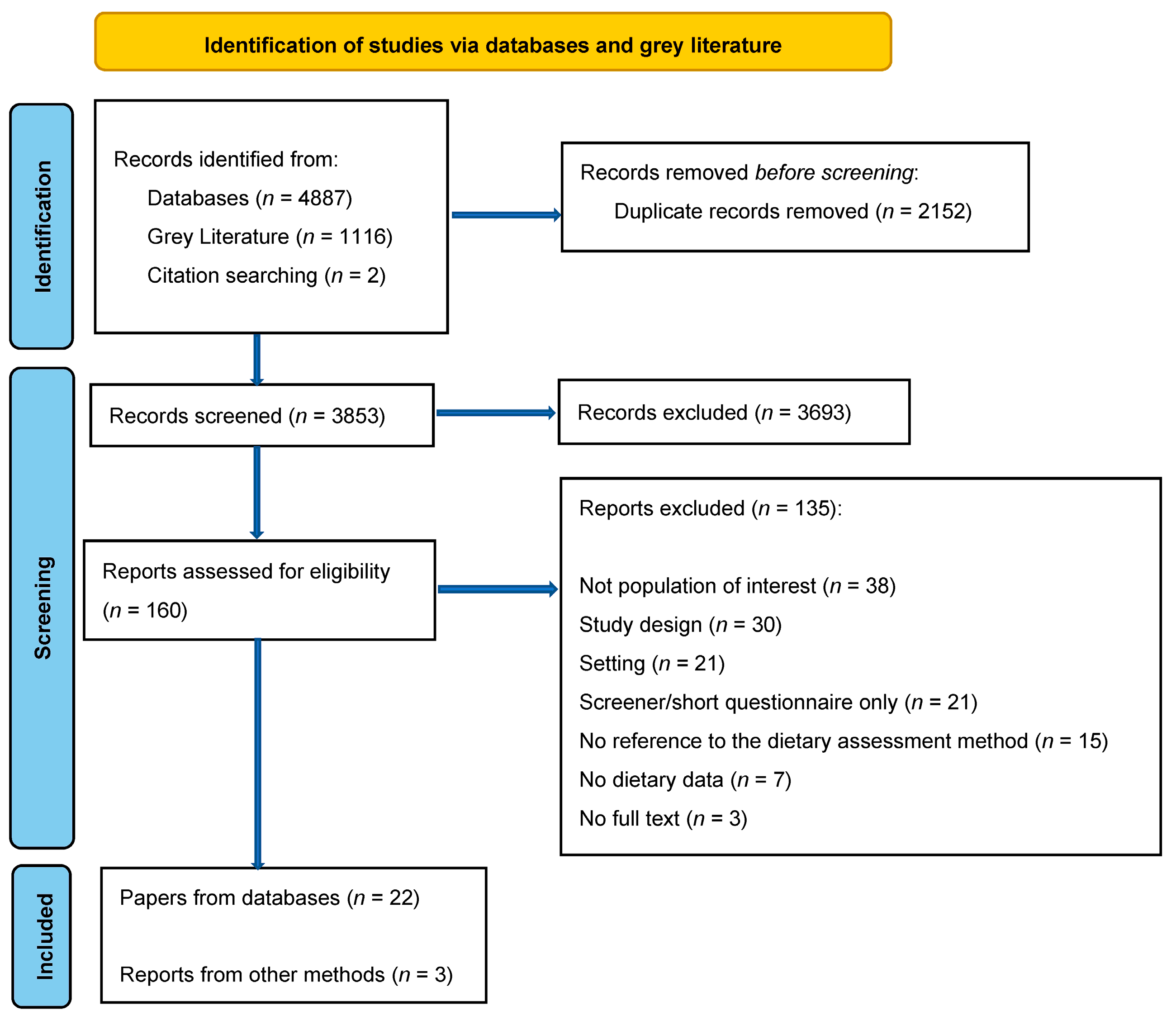

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.3. Dietary Assessment Methods

3.3.1. Store Data

3.3.2. Food Frequency Questionnaires

3.3.3. 24-h Recall

3.3.4. Weighed Food Records

3.3.5. Direct Observation

3.3.6. Conversational Methods

3.4. Reported Validity of Dietary Assessment Methods

3.5. Reported Strengths and Limitations to Assess the Applicability of Dietary Assessments

3.6. Quality Appraisal

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, K.; Mirraboopa, B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous and indigenist research. J. Aus. Stud. 2003, 27, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, C.; Wilson, R.; D’Angelo, S.; O’Reilly, G.M.; Mitra, B.; Hunter, K.; Kim, Y.; Rushworth, N.; Tee, J.; Hendrie, D.; et al. Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance: The Australian Traumatic Brain Injury National Data Project. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 888–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, T.L.; Anderson, K.; Garvey, G.; Cunningham, J.; Ratcliffe, J.; Tong, A.; Whop, L.J.; Cass, A.; Dickson, M.; Howard, K. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s domains of wellbeing: A comprehensive literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.; Wilson, R.; Delbridge, R.; Tonkin, E.; Palermo, C.; Coveney, J.; Hayes, C.; Mackean, T. Resetting the Narrative in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nutrition Research. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherwood, J. Colonisation—It’s bad for your health: The context of Aboriginal health. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 46, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Nutrition Results—Food and Nutrients, 2012–2013. Available online: https://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/5D4F0DFD2DC65D9ECA257E0D000ED78F/$File/4727.0.55.005%20australian%20aboriginal%20and%20torres%20strait%20islander%20health%20survey,%20nutrition%20results%20%20-%20food%20and%20nutrients%20.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Prior, D. Decolonising research: A shift toward reconciliation. Nurs. Inq. 2007, 14, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.T. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, 3rd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huria, T.; Palmer, S.C.; Pitama, S.; Beckert, L.; Lacey, C.; Ewen, S.; Smith, L.T. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: The CONSIDER statement. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, J. Do No Harm: Decolonising Aboriginal Health Research; University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gwynn, J.D.; Flood, V.M.; D’Este, C.A.; Attia, J.R.; Turner, N.; Cochrane, J.; Wiggers, J.H. The reliability and validity of a short FFQ among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous rural children. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooson, J.; Hutchinson, J.; Warthon-Medina, M.; Hancock, N.; Greathead, K.; Knowles, B.; Vargas-Garcia, E.; Gibson, L.E.; Bush, L.A.; Margetts, B.; et al. A systematic review of reviews identifying UK validated dietary assessment tools for inclusion on an interactive guided website for researchers: www.nutritools.org. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 60, 1265–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, E.; Wycherley, T.; O’Dea, K.; Brimblecombe, J. A comparison of dietary estimates from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey to food and beverage purchase data. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalan, S.; Farnbach, S.; Volk, L.; Gwynn, J.; Lock, M.; Trieu, K.; Brimblecombe, J.; Webster, J. What do we know about the diets of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia? A systematic literature review. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017, 41, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessarab, D.; Ng’andu, B. Yarning About Yarning as a Legitimate Method in Indigenous Research. Int. J. Crit. Indig. Stud. 2010, 3, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, A.W.; Welch, S.; Power, T.; Lucas, C.; Moles, R.J. Clinical yarning with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples—A systematic scoping review of its use and impacts. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, C.; Mackean, T.; Coombs, J.; Williams, H.; Hunter, K.; Holland, A.J.A.; Ivers, R.Q. Indigenous research methodology—Weaving a research interface. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2020, 23, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, D.L.; Vogliano, C.; Horsey, B.; Underhill, S.; Burkhart, S. Dietary assessment methodology and reporting in Pacific Island research: A scoping review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2021, 19, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Vanderlee, L.; Raffoul, A.; Stapleton, J.; Csizmadi, I.; Boucher, B.A.; Massarelli, I.; Rondeau, I.; Robson, P.J. Self-Report Dietary Assessment Tools Used in Canadian Research: A Scoping Review. Adv Nutr. 2017, 8, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfield, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K.; Kite, E.; Canuto, K.; Glover, K.; Gomersall, J.S.; Carter, D.; Davy, C.; Aromataris, E.; et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfield, S.; Pearson, O.; Morey, K.; Kite, E.; Glover, K.; Canuto, K.; Streak Gomersall, J.; Carter, D.; Davy, C.; Aromataris, E.; et al. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool: Companion Document. Adelaide, Australia: South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. 2018. Available online: https://create.sahmri.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Aboriginal-and-Torres-Strait-Islander-Quality-Appraisal-Tool-Companion-Document-1.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Christidis, R.; Lock, M.; Walker, T.; Egan, M.; Browne, J. Concerns and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples regarding food and nutrition: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porykali, B.; Davies, A.; Brooks, C.; Melville, H.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Coombes, J. Effects of Nutritional Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Health Outcomes in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.K.; O’Dea, K. The role of energy cost in food choices for an Aboriginal population in northern Australia. Med. J Aust. 2009, 190, 549–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Liddle, R.; O’Dea, K. Use of point-of-sale data to assess food and nutrient quality in remote stores. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.; Ferguson, M.; Chatfield, M.D.; Liberato, S.C.; Gunther, A.; Ball, K.; Moodie, M.; Miles, E.; Magnus, A.; Mhurchu, C.N.; et al. Effect of a price discount and consumer education strategy on food and beverage purchases in remote Indigenous Australia: A stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e82–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brimblecombe, J.K.; Ferguson, M.M.; Liberato, S.C.; O’Dea, K. Characteristics of the community-level diet of Aboriginal people in remote northern Australia. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 198, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Apparent dietary intake in remote aboriginal communities. Aust. J. Public Health 1994, 18, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J. Aboriginal dietary intake and a successful nutrition intervention project in a Northern Territory community. Aust. J. Nutr. Diet. 1993, 50, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J.; Bailey, A.P.V.; Yarmirr, D.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Survival tucker: Improved diet and health indicators in an Aboriginal community. Aust. J. Public Health 1994, 18, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; Bonson, A.P.V.; Yarmirr, D.; O’Dea, K.; Mathews, J.D. Sustainability of a successful health and nutrition program in a remote Aboriginal community. Med. J. Aust. 1995, 162, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, R.; Rowley, K.G.; O’Dea, K.; Lee, A.J.; Knight, S. Increase in prevalence of obesity and diabetes and decrease in plasma cholesterol in a central Australian aboriginal community. Med. J. Aust. 2000, 172, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, K.G.; Su, Q.; Cincotta, M.; Skinner, M.; Skinner, K.; Pindan, B.; White, G.A.; O’Dea, K. Improvements in circulating cholesterol, antioxidants, and homocysteine after dietary intervention in an Australian Aboriginal community. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson-Briggs, S.; Jenkins, A.; Ryan, C.; Brazionis, L.; the Centre for Research Excellence in Diabetic Retinopathy Study, G. Health-risk behaviours among Indigenous Australians with diabetes: A study in the integrated Diabetes Education and Eye Screening (iDEES) project. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Jenkins, A.; Ryan, C.; Keech, A.; Brown, A.; Boffa, J.; O’Dea, K.; Bursell, S.E.; Brazionis, L.; CRE in Diabetic Retinopathy and the TEAMSnet Study Group. Health-related behaviours in a remote Indigenous population with Type 2 diabetes: A Central Australian primary care survey in the Telehealth Eye and Associated Medical Services Network [TEAMSnet] project. Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W. A dietary survey of aborigines in the Northern Territory. Med. J. Aust. 1953, 2, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouris-Blazos, A.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Indigenous Australian food culture on cattle stations prior to the 1960s and food intake of older Aborigines in a community studied in 1988. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 9, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlqvist, M.L.; Kouris, A.; Gracey, M.; Sullivan, H. An anthropological approach to the study of food and health in an indigenous population. Food Nutr. Bull. 1991, 13, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.; Smith, A.; Mathews, J.D.; Bryce, S.; O’Dea, K.; Rutishauser, I.H.E. Measuring dietary intake in remote australian aboriginal communities. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1995, 34, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamien, M.; Nobile, S.; Cameron, P.; Rosevear, P. Vitamin and nutritional status of a part Aboriginal community. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1974, 4, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamien, M.; Woodhill, J.M.; Nobile, S.; Rosevear, P.; Cameron, P.; Winston, J.M. Nutrition in the Australian aborigine. Dietary survey of two aboriginal families. Food Technol. Aust. 1975, 27, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rabuco, L.B.; Rutishauser, I.H.E.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Dietary and plasma retinol and beta-carotene relationships in filipinos, non-aboriginal and aboriginal australians. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1991, 26, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, M.; Billington, B.P.; Hodges, K.T.; Specht, R.L. Nutrition and health (1948) of Aborigines in settlements in Arnhem Land, northern Australia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 9, 164–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryce, S.; Scales, I.; Herron, L.M.; Wigginton, B.; Lewis, M.; Lee, A.; Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women’s Council. Maitjara Wangkanyi: Insights from an Ethnographic Study of Food Practices of Households in Remote Australian Aboriginal Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longstreet, D.; Heath, D.; Savage, I.; Vink, R.; Panaretto, K. Estimated nutrient intake of urban Indigenous participants enrolled in a lifestyle intervention program. Nutr. Diet. 2008, 65, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Brady, M. Diet and Dust in the Desert: Life in the Early Years of Oak Valley Community, Maralinga Lands, South Australia, 2nd ed.; Aboriginal Studies Press: Canberra, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.J.; Sheard, J. Store Nutrition Report. Final Store Turnover Food and Nutrition Results. Nganampa Health Council. Available online: https://www.nganampahealth.com.au/nganampa-health-council-documents/category/12-programs?download=46:store-nutritional-report (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing—Counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/census-population-and-housing-counts-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-australians/2021 (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Lovett, R.; Lee, V.; Kukutai, T.; Cormack, D.; Rainie, S.; Walker, J. Good Data Practices for Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance. In Good Data; Daly, A., Devitt, S.K., Mann, M., Eds.; Institute of Network Cultures: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M.; Maddox, R.; Booth, K.; Maidment, S.; Chamberlain, C.; Bessarab, D. Decolonising qualitative research with respectful, reciprocal, and responsible research practice: A narrative review of the application of Yarning method in qualitative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Int. J. Equity Health 2022, 21, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dietary Assessment Method | Study Design | Population | Aims * | Dietary Components Assessed | Location | Study Name (If Applicable) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Store data | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (n = 1700) | Explore the relationship between dietary quality and energy density of foods (MJ/kg) and energy cost ($/MJ) for an Aboriginal population living in a remote region | Contribution of food groups to dietary energy and dietary cost | Island community, Northern Australia | N/A | Brimblecombe et al., 2009 [26] |

| Store data | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (n = 185–880; across 6 communities) | To examine the feasibility of using point-of-sale data to assess dietary quality of food sales in remote stores | 1- nutrient profiles (macronutrient contribution to energy and nutrient density—nutrient/1000 kJ); 2- major food sources of macro- and micronutrients | Remote Australia, three states & NT | Remote Indigenous Stores and Takeaway Project (RIST) | Brimblecombe et al., 2013 [27] |

| Store data | Stepped wedge randomised controlled trial | Community Rural/remote (n = 8515; 20 communities) | To measure the effect of a price discount on food and drink purchases with and without an instore consumer education strategy applied at the population level | Population intake and estimated intake/capita. Purchases in grams of fruit and vegetables, water, artificially sweetened soft drinks, SSB, healthy food, discretionary food, other beverages, and Australian Health Survey food groups and nutrients | NT (20 remote Indigenous communities) | Store Healthy Options Project in Remote Indigenous Communities (SHOP@RIC) | Brimblecombe et al., 2017 [28] |

| Store data | Multi-site 12-month audit | Community Rural/remote (n = 2644; 3 communities) | To describe the nutritional quality of community-level diets in remote northern Australian communities | Community-level dietary intake (energy, food type, quantity, micronutrients and macronutrients, and food sources of nutrients) | NT (3 remote communities) | N/A | Brimblecombe et al., 2013 [29] |

| Store data | Non-randomised trial with baseline as control | Community Rural/remote (n = 154 (mean)) | Summarise the development and testing of the store-turnover method, a non-invasive dietary survey methodology in remote, centralised Aboriginal communities | Changes in nutrient density over intervention period and changes in apparent consumption of targeted foods (e.g., fruit and vegetables, wholemeal bread, white sugar) | NT (Minjilang, Croker Island) | Minjilang Health and Nutrition Project | Lee 1993 [31] |

| Store data | Non-randomised trial with baseline as control | Community Rural/remote | To describe an unusually successful health and nutrition project initiated by the people of Minjilang | Apparent community dietary intake and change—changes in nutrient density and apparent consumption compared to biological markers | NT (Minjilang, Croker Island) | Minjilang Health and Nutrition Project | Lee et al., 1994 [32] |

| Store data | Non-randomised trial with baseline as control | Community Rural/remote | Assess the long-term effect of a nutrition program in a remote Aboriginal community and report the nutritional outcomes up to 1993 after monitoring ceased in June 1990 | Changes in dietary intake of target foods (including fruit, vegetables, and wholegrain bread) and nutrients (including folate, ascorbic acid, and thiamine) | NT (Minjilang, Croker Island) | Minjilang Health and Nutrition Project | Lee et al., 1995 [33] |

| Store data | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (n = 1617; 6 communities) | Describe the apparent per capita food and nutrient intake in six remote Australian Aboriginal communities | Mean daily dietary intake per capita. Contribution of macronutrients to total energy | NT (6 remote communities—3 central desert, 3 northern coastal) | N/A | Lee et al., 1994 [30] |

| Store data | Cross sec-tional | Community Rural/remote (total population not specified) | To document change in prevalence of obesity, diabetes, CVD risk factors, and trends in dietary macronutrient intake over an eight-year period in a rural Aboriginal community | General trends in food consumption expressed as nutrient density (sugar, total fat, saturated fat, complex carbohydrates as percentage of total energy) | NT (Rural community) | N/A | McDermott et al., 2000 [34] |

| Store data | Pre and post survey | Community Rural/remote (total population not specified) | Evaluate the effectiveness of a community-directed intervention program to reduce coronary heart disease risk through dietary modification | Changes in dietary quality | WA (Kimberley region) | Looma Healthy Lifestyle Program | Rowley et al., 2001 [35] |

| Store data | Cross-sectional and retrospective comparision | Community Rural/remote (n = 1646; 5 communities) | To provide feedback to relevant Councils to help inform decision making on key issues and to identify changes in food supply 1986–2012 | Energy, macronutrient, and micronutrient data. Results compared with dietary recommendations from ADGs and reported separately for each store | SA (Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands) | N/A | Lee et al., 2013 [49] |

| FFQ | Cross-sectional | Individual Rural/remote (n = 135) | To assess prevalence of modifiable health-risk behaviours among Indigenous Australian adults with diabetes | Food group intake including: vegetables, fruit, fish, takeaway meals, liquids (water, milk, juice, diet and regular soft drink), snacks | VIC (Mooroopna) | Diabetes Education and Eye Screening (iDEES) project | Atkinson -Briggs et al., 2022 [36] |

| FFQ | Cross-sectional study | Individual Rural/remote (n = 209) | To describe health behaviours of Indigenous Australians with diabetes attending a primary care clinic | Frequency of food group intake of: vegetables, fruit, fish, takeaway meals, liquids (water, milk, juice, diet and regular soft drink), snacks | NT (Remote community clinic, Alice Springs) | TEAMsnet project | Xu et al., 2019 [37] |

| FFQ (Modified “food list” and questionnaire method) | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (17 settlements; population range: 23–300) | Evaluate the dietary intake, food consumption patterns, and eating habits of Aborigines* living on government settlements, missions, and cattle stations | Total food intake per week (meat, sugar, tea, flour, cereal and bread, fruits and vegetables). Intake of specific nutrients (vitamin C, calcium, vitamin A) | NT (Darwin, Gulf of Carpentaria, Alice Springs, Barkly Tableland) | N/A | Wilson 1953 [38] |

| RAP- modified FFQ Interviewing ‘key’ informants Focus groups | Cross-sectonal | Community Rural/remote (n = 25) | Review the published qualitative data using RAP to describe distant past food intake on cattle stations prior to the 1960s and food intake of Aborigines* aged 50 and over in 1988 in Junjuwa | Contribution of individual foods consumed to diet quality | WA (Junjuwa, Fitzroy Crossing) | ‘Food Habits in Later Life’ (FHILL) Program 1988–1993 | Kouris-Blazos & Wahlqvist 2000 [39] |

| RAP-modified FFQ Weighing of food Observation Group discussions | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (n = 15) | Ascertain the major nutritional problems in an Aboriginal Australian elderly community, document the risk factors, especially dietary, that may be contributing to the deterioration in health | Average daily intake of energy, protein, fat, carbohydrates. Food habits, including quality and quantity of foods consumed on “binge” days versus “lean” days | WA (Junjuwa) | ‘Food Habits in Later Life’ (FHILL) Program 1988–1993 | Wahlqvist et al., 1991 [40] |

| WFR 24-h recall FFQ Diet history Store data | Cross-sectional comparision | Community Rural/remote (coastal n = 302; desert n = 247; weighed and recalled intake n = 41) | Identify a practical quantitative dietary survey methodology acceptable to remote Aboriginal communities, to assess the face validity of each method and to compare quantitative data obtained | Macro and micronutrients, percent energy derived from protein, total carbohydrate, fat, sugars, complex carbohydrate, apparent consumption of food groups | Northern coastal community and central desert community (anonymous) | N/A | Lee et al., 1995 [41] |

| WFR 6-day Observation Questioning | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (n = 720) | Reports the extent of vitamin deficiency in a community of part-Aboriginal* community | Foods available and consumed and micronutrients content. Weighed food record used to confirm community level dietary observations | NSW (Bourke) | N/A | Kamien 1974 [42] |

| WFR 6-day (Mon-Sat) | Cross-sectional | Individual Rural/remote (n = 17) | A detailed investigation of diet and nutrition of two Aboriginal families, to assess prevalence the extent of biochemical and clinical nutrition deficiency found amongst the Aboriginal population of Bourke | Food groups, intake and percent contribution to calories, protein and micronutrients | NSW (Bourke) | N/A | Kamien 1975 [43] |

| WFR 28-day | Cross-sectional | Individual Rural/remote (n = 23) | Investigate possibility that dietary factors other than vitamin A, influence plasma retinol and beta-carotene level in apparently healthy adult individuals consuming their usual diet | Energy, macronutrients, retinol, beta-carotene and total vitamin A, dietary fibre and zinc | WA (Fitzroy Crossing) | N/A | Rabuco et al., 1991 [44] |

| Observation | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (total population not specified) | Provide a general report of food consumption and dietary levels of the Aborigines* at the settlements. Biochemical tests to assist in assessment of nutritional status | Calories, protein, iron, calcium, specific vitamins | NT (Four settlements in Arnhem Land) | American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land | McArthur et al., 2000 [45] |

| Observation Conversational methods 24-h recall | Cross-sectional | Household Rural/remote (13 households with 4–13 occupants) | 1. What food and drinks Anangu families are eating; and 2. Factors that influence these food choices | Food and drinks consumed, foods and drinks purchased. Collection of receipts. Records of food preparation: how, when and who was eating. Food groups as defined in the ADGs, and energy and macronutrient content | SA (Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands) | Maitjara Wangkanyi (“talking about food”) | Bryce et al., 2020 [46] |

| Observation Adapted store data Adapted 24-h recall | Cross-sectional | Community Rural/remote (n = 69) | An anthropological study to provide information on the diet and lifestyle of the Aboriginal owners of Maralinga and Emu to determine possible options for the future rehabilitation of the Maralinga lands | Average consumption in grams per capita per day for a range of bush foods and store foods | SA (Oak Valley, Maralinga Lands) | N/A | Palmer & Brady 1991 (2nd ed. 2021) [48] |

| Multiple-pass 24-h recall (baseline and 12 months) and casual ‘yarn’ | Prospective cohort | Community Urban (n = 100) | Evaluate reported change in nutrient intake of adult urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who participated in a medically based lifestyle intervention program | Nutrient intake and food group serves | QLD (Townsville) | Walk-about Together Program (WAT) | Longstreet et al., 2008 [47] |

| 24-h recall (2 at least 8 days apart in non-remote areas and one in remote areas) | Cross-sectional survey | National Rural/remote /urban (n = 4109) | Collect detailed nutrition information from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | Food groups, energy, and nutrient intakes | Australia | National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey 2012 -2013 (NATSINPAS) | Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015 [6] |

| Methods Identified in Review | Reported Strengths | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| URBAN POPULATIONS | ||

| 24-h recall [47] | 35% rate of underreporting identified in the study compares to underreporting identified in other studies, suggesting appropriateness of method [47]. Strategies used identified as helpful by participants similar to those used with other populations [47]. | Underreporting likely attributable to social desirability of lower intake [47]. Weekend intake missed if recalls cover weekdays only [47]. Intake of bush foods may be underreported if more often consumed on weekends and recall focuses on weekdays [47]. |

| RURAL POPULATIONS | ||

| FFQ [36,37,38,39,40,41] | Questionnaire adapted to include checklist of geographically specific bush foods [39,40]. Portion size estimates able to be assisted with photographs, food scales, play dough, and items from supermarket [40]. | Self-reporting may lead to bias towards perceived correct answers e.g., underreporting discretionary foods [36,37]. Unreliable recollection [36]. Converting intake frequency using standard serving sizes may underestimate serves if actual serving sizes larger than standard [37]. Modified questionnaire likely insensitive to gender difference in intake [39]. Issues with questionnaire requiring understanding of concepts of ‘time’, ‘frequency’, and ‘quantity’ [39,40]. Produced list of foods eaten at some point or enjoyed not actual intake [41]. |

| Modified food list/ questionnaire [38] | None identified. | Data based on food amounts issued rather than consumed [38]. Risk of no allowance for seasonal variations [38]. Uneven distribution of food and wastage not accounted for [38]. No consideration of bush foods consumed [38]. |

| WFR [41,42,43,44] | None identified. | Presence of strangers at meals may change eating habits [43]—weighing of food carried out by survey team who were present during meal preparation and at meal times. Participants anxious to present a good image [43]. Timing of assessment during periods of employment and pension week resulting in greater food purchases than usual [43]. Reported non-compliance during recording of food [44]. Poor compliance for record greater than one day, linked to timing of traditional ceremonies and financial difficulties [41]. Close supervision provided (at least 3 times per week, often daily) to facilitate compliance [44]. Difficultly ensuring all foods consumed were weighed and observed [41]. Low cultural acceptance of usefulness of quantitative measures of intake [41]. |

| Diet history [41] | None identified. | Difficulties stating ‘usual’ intake may be related to significant day-to-day variability in diet [41]. |

| 24-h recall [41,46,48] | Minimal questioning or use of probes during recall and without attempts to estimate portion sizes * [46]. May be adapted to best suit circumstances such as visiting participants twice per day (every 12 h) and asking about foods eaten in the last 12 rather than 24 h [48]. Helped confirm frequency of ‘hungry’ days (i.e., days where two or more meals missed or minimal food consumed) [46]. | Foods frequently underestimated (sugar, sweetened beverage) and others overestimated (fruit, veg, and traditional foods) [41]. Evidence of selective recall and bias in responses may be related with tendency to ‘please’ interviewer [41]. Difficulties repeating method with same participants due to frequent population movement [48]. |

| Observation/conversational methods [42,45,46,48] | Considers factors influencing food choices (e.g., food shopping and cooking observed) [46,48]. Allows inclusion of difficult to quantify foods or foods that may be omitted from store sales data such as bush foods and foods entering community through other avenues e.g., visitors [48]. Allows contextual dietary information to be collected (e.g., income, number of household members/visitors who ate foods, cooking facilities, number of ‘hungry’ days, eating patterns) [46]. Greater control over disclosure for participants [46]. | Inability to accurately quantify and describe food gathered particularly on weekends [45]. Prescence of observers influences foods procured and consumed [48]. Reliance on method may contribute to underestimation of consumption of bush foods and foods bought by visitors [48]. |

| Focus groups/ group discussions [39,40] | Reveals food quality and quantity of consumption closely connected to weekly pension [39]. RAP (open ended question approach) allowed questions on health and lifestyle as well as food intake [40]. | None identified. |

| Store data [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,41,48,49] | Assess dietary quality of food sales in remote community stores, trends in intake between communities [27]. Objective proxy for community-level dietary intake where community stores provide main source of food [27,28,30,31,32,41]. Specific to relatively small geographical areas [41]. Efficient and inexpensive [30,31,32,41]. Relatively non-invasive [30,32,41]. Higher acceptability to communities compared to individual dietary intake methods [41]. Less potential for bias as no reliance on subjective assessment of intake and avoids language, literacy, and numeracy factors that may reduce reliability of direct measurement or recall [30,41]. Allows for retrospective data to be collected [41]. Seasonal variation in intake may be determined [32]. Allows for within-store comparison, e.g., changes in purchasing data [28]. Can identify contributions of specific food and beverage items for targeted community-based intervention strategies and policy [27,30]. Can be used to evaluate impact of community-based nutrition programs [30,31,32]. Can be utilised by Aboriginal researchers and health workers within communities for increased community involvement in health research and promotion [41]. Gathered nutrition information may be easily relayed to communities in culturally specific ways [30]. | Provides estimate of food and nutrient availability, not actual intake [27]. Usefulness dependant on contribution of store to overall population-level diet [27]. Large variation in fortnightly sales [28]. Insensitive to food preparation and cooking methods [27,35]. Does not account for wastage after purchase [27,30,48]. Does not account for food/beverages obtained outside store, e.g., bush food [26,30,35,49]. Estimates of community-level energy/nutrient intakes rely upon accurate population estimates, problematic where population mobility high [27,29,30,41,48]. Cannot assess food distribution patterns within the community [30,41,48]. Cannot identify individual or sub-group dietary intake or diet composition [30]. Estimated dietary quality limited by accuracy of food composition databases, e.g., nutrient composition of perishable items may be impacted by long-distance transportation [27,30]. Errors in measurement in method such as missing invoices, stock with very slow turnover [30]. Not adequate for nutritional surveillance of community [41]. |

| NATIONAL DATA | ||

| 24-h recall [6] | To account for seasonal variations in nutrition may be conducted over 12-month period [6]. Trained interviewers can conduct interviews [6]. Can be conducted in non-remote and remote areas [6]. | Underreporting and social desirability bias, especially with discretionary food intake [6]. Systematic underreporting risk with children unable to recall intakes and carers may be unaware of total intake of child [6]. Difficulties comparing results with guidelines and risk of overestimation of proportion meeting recommendations if units different to guidelines (e.g., whole serves where guidelines for some sex/age groups are half serves) [6]. Reliability may be influenced by sampling error [6]. Risk of undercoverage (i.e., difference between population represented by the sample size of the survey and the in scope population) [6]. Difficulty conducting second recall in remote areas [6] Accuracy of recall data dependent on accuracy of measures, food databases [6]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davies, A.; Coombes, J.; Wallace, J.; Glover, K.; Porykali, B.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Kunzli-Rix, T.; Rangan, A. Yarning about Diet: The Applicability of Dietary Assessment Methods in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians—A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030787

Davies A, Coombes J, Wallace J, Glover K, Porykali B, Allman-Farinelli M, Kunzli-Rix T, Rangan A. Yarning about Diet: The Applicability of Dietary Assessment Methods in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians—A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(3):787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030787

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavies, Alyse, Julieann Coombes, Jessica Wallace, Kimberly Glover, Bobby Porykali, Margaret Allman-Farinelli, Trinda Kunzli-Rix, and Anna Rangan. 2023. "Yarning about Diet: The Applicability of Dietary Assessment Methods in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians—A Scoping Review" Nutrients 15, no. 3: 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030787

APA StyleDavies, A., Coombes, J., Wallace, J., Glover, K., Porykali, B., Allman-Farinelli, M., Kunzli-Rix, T., & Rangan, A. (2023). Yarning about Diet: The Applicability of Dietary Assessment Methods in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians—A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 15(3), 787. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030787