Abstract

Hormonal fluctuations, excessive clothing covering, sunscreen use, changes in body fat composition, a vitamin D-deficient diet, and a sedentary lifestyle can all predispose postmenopausal women to vitamin D deficiency. An effective supplementation plan requires a thorough understanding of underlying factors to achieve the desired therapeutic concentrations. The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the predictors that affect vitamin D status in postmenopausal women. From inception to October 2022, we searched MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and clinical trial registries. Randomized clinical trials of postmenopausal women taking supplements of vitamin D with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) measurement as the trial outcome were included. Two independent reviewers screened selected studies for full-text review. The final assessment covered 19 trials within 13 nations with participants aged 51 to 78. Vitamin D supplementation from dietary and pharmaceutical sources significantly increased serum 25(OH)D to optimal levels. Lower baseline serum 25(OH)D, lighter skin color, longer treatment duration, and prolonged skin exposure were all associated with a better response to vitamin D supplementation in postmenopausal women.

Keywords:

menopause; vitamin D status; 25-hydroxyvitamin; 1,25(OH)D; vitamin D deficiency; nutrients 1. Introduction

Menopause marks a significant shift in vitamin D requirements. Postmenopausal women are particularly predisposed to vitamin D deficiency due to changes in body composition, increased age, race, inadequate sun exposure, lack of vitamin D dietary consumption, and adiposity [1,2,3,4,5]. It is becoming increasingly clear from the evidence that vitamin D deficiency is linked to various menopausal health conditions, such as vasomotor symptoms [6], vaginal atrophy or genitourinary syndrome of menopause [7,8,9], sexual dysfunction [10], and postmenopausal osteoporosis [11]. With the recognition of widespread vitamin D deficiency and its impact on the health and well-being of postmenopausal women, the importance of accurate vitamin D status assessment and a thorough understanding of the determinants of vitamin D supplementation in this population is becoming more widely recognized.

The large interlaboratory variations in assay methods used to measure 25(OH)D serum levels, the best measure of vitamin D status [12], have made defining vitamin D sufficiency difficult. Moreover, different patient characteristics and vitamin D inadequacy thresholds partly explain variations in optimal serum concentrations reported by clinical trials. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) [13], the Institute of Medicine (IMO) 2010 [14], the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guidelines [15], and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists [16] defined vitamin D deficiency as below 20 ng/mL and sufficiency as ≥30 ng/mL. These limits were established in response to evidence that secondary hyperparathyroidism becomes more common when serum 25(OH)D levels fall below 30 ng/mL.

Several interventional studies have revealed that a variety of factors influence vitamin D status and the effects of vitamin D supplementation. Body mass, basal serum 25(OH)D levels, and season of the year have all been found to be significant predictors of the vitamin D supplementation response and the impact on its status [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Additionally, genetic studies have demonstrated that the genotype affects serum vitamin D levels. However, findings on genetic diversity’s effect on the vitamin D supplementation response are limited [24,25,26,27,28].

Disparities in the ideal blood concentration, dose, and duration of vitamin D administration highlight the importance of considering the many factors influencing vitamin D status during menopause when implementing a supplementation plan. This is critical, given the high prevalence of vitamin D-related conditions in postmenopausal women. This review aimed to collect evidence on the factors that influence the response to vitamin D supplementation from dietary and pharmaceutical sources, as well as their impact on vitamin D status in postmenopausal women.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Protocol and Guidance

The International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (INPLASY) assigned this protocol the registration number INPLASY202260116. This systematic review followed the recommended reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [29]. Before conducting the actual search, the protocol and search strategy were peer-reviewed. This systematic review did not require any ethical approval.

2.2. Databases Searched and Search Strategy

The review team conducted an initial search for vitamin D-related systematic reviews and identified the literature relevant to the review questions. To validate and peer review the search strategy, the PRESS Checklist was used to evaluate the quality and completeness of the electronic search strategy [30]. We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed) from 1977 to 14 October 2022, Embase (via OvidSP) to 14 October 2022, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) to 14 October 2022, CINHAL (EBSCO) from 1999 to 14 October 2022, Web of Science Core Collection from 1970 to 14 October 2022, and Scopus from 2009 to 14 October 2022. We also looked for ongoing trials on clinical trial registries such as ClinicalTrials.gov, the ISRCTN registry (https://www.isrctn.com, last accessed on 14 October 2022), and the EU Clinical Trials Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu, last accessed on 14 October 2022). There were no restrictions on the publication date or language. The search terms and strategies were developed using the PICO (Patients, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) model. The complete MEDLINE search strategy is described in Supplementary File. Search strategies were adjusted for each database searched. Each search was conducted three times, each by a different reviewer. The databases were last searched on 14 October 2022. We also included any publications brought to our attention by subject matter experts.

2.3. Study Selection

The identification of references was completed in two stages. First, all studies published from inception to October 2022 that assessed vitamin D status in postmenopausal women and associated factors were identified. EndNote 20.4 was used to import the identified studies, and duplicates were removed. Then, the remaining records were exported to Covidence Software for further screening and data extraction. Two reviewers independently assessed the eligibility of the title and abstract in an unblended standardized manner (M.M.H. and H.Z.H.). A record was included for full-text review if at least one reviewer coded it as potentially eligible. Irrelevant studies were omitted. Full texts were obtained for further review if a decision could not be reached based on the information provided in the abstract. Differences in data extraction were settled by referring to original articles and discussions in order to reach an agreement. The senior reviewer (H.Z.H.) made the final decision based on the established eligibility criteria. Additional studies were manually retrieved from the references cited in the critical articles chosen for evaluation.

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion of Studies

All randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, single-blind trials conducted in humans and published in any language were eligible. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) postmenopausal women with physiological or iatrogenic causes, (2) administration of vitamin D, regardless of the source or dose, (3) at least one outcome of interest, including serum 25(OH)D or one of its metabolites, 1,25(OH)D, and (4) comparison of the outcome of interest between any pair of the following: other doses or forms of vitamin D supplementation or placebo. Abstracts were included if they contained enough information to allow data extraction. Cross-sectional, observational, and non-human studies, case reports, and trials with and without end-of-trial outcomes were excluded. We pilot-tested the eligibility criteria on a sample of reports (n = 6) to refine and clarify the criteria and ensure reproducibility in future research.

2.5. Strategy for Data Extraction and Synthesis

Three reviewers conducted the extraction process independently to minimize bias and error (M.M.H., H.Z.H., and A.R.A.). A systematized data extraction sheet was used to extract data from each record. All pertinent data were extracted from the records, and no additional information was obtained from the authors. Citations for each article were extracted, as well as the study’s first author, full title, publication date, study design, study aim, eligibility criteria, participant characteristics, types of interventions and comparators (including dosage forms, dose, and frequency), total number of participants, adverse outcomes, and study outcomes measures. Potential confounders in randomized clinical trials, if the trial was uncontrolled, the analysis technique or assay of serum 25(OH)D, and the attrition rate were also reported. We attempted to contact the authors of studies that were only published as abstracts in order to obtain more information about the study methodology.

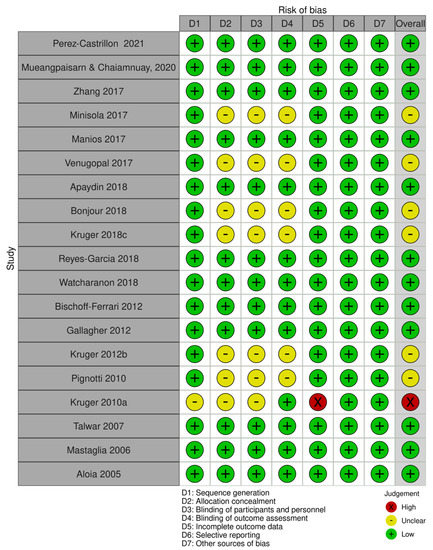

2.6. Risk of Bias (RoB) Assessment

Two reviewers (M.M.H. and H.Z.H.) assessed the methodological quality of the included studies, and one reviewer (A.R.A.) arbitrated conflicts that were not due to assessor error using the Cochrane RoB 2.0 quality assessment. All included studies were evaluated for bias following the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3, 2022 [31]. Sequence generation, allocation concealment, the blinding of participants and personnel, the blinding of the outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting were all investigated as potential areas of bias. Each item was assigned a RoB of low, unclear, or high.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

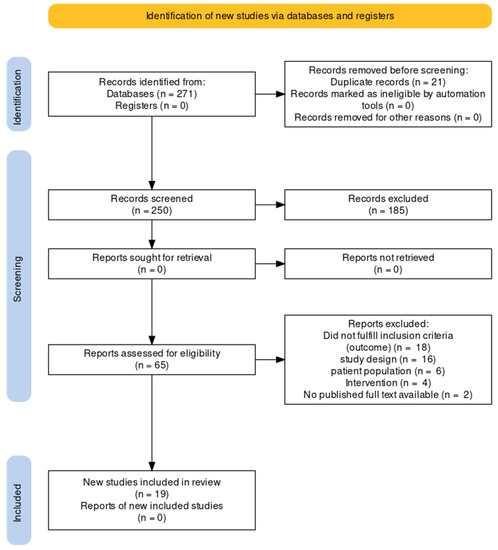

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase (via OvidSP), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, CINHAL (EBSCO), Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, and Scopus. The search produced 271 records. There were 21 duplicates, and the remaining 250 were screened for titles and abstracts. Covidence Software was used to screen records (titles and abstracts), review full-text articles, and extract data. During the title and abstract screening, we excluded an additional 185 records because of irrelevance to the review subject, and the remaining 65 were full-text reviewed (Figure 1). Following a search of clinical trial registries, no additional records were found. Eventually, 19 trials were included in the final review [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics

All 19 included studies were randomized clinical trials published in English between 2005 and October 2021. The trials included 13 countries (Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Indonesia, Spain, Italy, France, Greece, Switzerland, Turkey, Brazil, Argentina, and USA). The 19 trials included a total of 4677 subjects. The sample size ranged from n = 20 to n = 2077. All 19 trials were conducted on postmenopausal women who ranged in age from 51 to 78 years old. Women with osteoporosis were included in four trials [41,44,45,48]. The durations of interventions ranged from 8 weeks to 3 years. Six trials administered vitamin D as a dietary supplement (fortified milk, yogurt, or cheese) [35,37,38,39,40,46]. Other trials provided vitamin D in the form of oral supplements of vitamin D2, vitamin D3, and calcidiol. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the key findings and participant characteristics from the studies included.

Table 1.

Key findings of the included trials.

Table 2.

The study participant characteristics.

3.3. Risk of Bias

The RoB assessment is detailed in Figure 2. Except for one trial [39], all trials were rated as having a low or unclear risk of bias in all aspects considered. Nine of them were double-blind to both participants and investigators [32,33,34,36,43,44,46,47,50], and one was single-blinded to participants [40]. In six trials, there was an unclear degree of selection, performance, and detection bias due to a lack of information on randomization and the concealment of the intervention allocation [35,37,38,40,45,48]. One trial had a high dropout rate (n = 94) for personal reasons [46]. The lack of assay standardization of serum 25(OH)D serum levels was a source of concern for all studies.

Figure 2.

Risk-of-bias assessment [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50].

4. Discussion

We consider our work to be the first systematic review and a key investigation that compiled existing evidence on the effects and predictors of vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D status in postmenopausal women. Postmenopausal women are the most affected by vitamin D deficiency and the most likely to benefit from effective vitamin D supplementation. Additionally, the lack of agreement on optimal and adequate vitamin D supplementation plans in postmenopausal women has pushed this to the forefront of medical research. The findings of the 19 trials revealed that the factors linked to vitamin D status in menopausal women could be classified into two major categories: factors related to vitamin D supplementation dosage regimens, including the dose administered, frequency, formulation, and duration of treatment, and factors related to patients’ characteristics and demographics, including serum baseline, lifestyle habits, ethnicity, and genetics.

4.1. The Effect of Treatment Duration and Dose on Vitamin D Status

Different trials have investigated the effects of various forms and dosages of vitamin D supplementation on overall vitamin D status. A high single oral dose of 300,000 IU was found to be superior to low doses of 800 IU/day and shown to significantly increase the vitamin serum concentration [33]. Another study concluded the same with a dose of 250,000 IU of vitamin D [51]. On the other hand, Pignotti et al. concluded that low doses of 400 IU/day were ineffective at raising serum concentrations of 25(OH)D to levels considered optimal for bone health [45]. In both trials, with the administration of high doses, serum 25(OH)D returned to baseline after three months. This highlights that a maintenance dose with regular intervals would be reasonable in patients undergoing single-, large-dose vitamin D replacement. Mueangpaisarn and Chaiamnuay et al. found the same with doses of 40,000 IU and 100,000 IU of cholecalciferol after three months of treatment [43].

4.2. The Effects of Type of Vitamin D on Vitamin D Status

It has also been proposed that the type of vitamin D affects vitamin D status. Vitamin D2 was found to be effective at increasing serum 25(OH)D concentrations but required higher than the usual recommended doses of vitamin D3 [41]. Several studies have found that the response of serum 25(OH)D to vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation differs, with vitamin D2 being less effective than vitamin D3 [52,53,54,55]. Research attributed these differences in response between the two calciferol forms to differing affinities for the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which appear to be related to an additional step of 24-hydroxylation that inactivates calcitriol [56,57]. Moreover, it is hypothesized that vitamin D3 is potentially a more favorable substrate for 25-hydroxylase [58].

Bischoff et al. found that supplementation with the 25(OH)D3 metabolite itself is more effective and faster than vitamin D3 in raising 25(OH)D levels in postmenopausal women, compared to typical doses of 800 IU vitamin D3 [34,44]. This is because 25(OH)D3 is hydrophilic, has a much shorter half-life, and causes a rapid rise in serum 25(OH)D levels. Furthermore, the fact that 25(OH)D3 enters the circulation and bypasses first-pass metabolism makes it preferable when the fast replacement of 25(OH)D is required [59,60]. These findings are consistent with many previous studies [61,62,63,64,65,66]. Minisola et al. studied different doses of calcidiol (20, 40, and 125 ug/day) in postmenopausal women and found that all dosage regimens significantly increased serum 25(OH)D at the end of the treatment of 12 weeks; however, no difference was noticed between vitamin D-insufficient and vitamin D-deficient patients [42].

4.3. The Effects of Baseline Serum 25(OH)D on Vitamin D Status

Venugopal et al. found that large doses of 25,000 IU/4 weeks and 50,000 IU/4 weeks of cholecalciferol can maintain vitamin D sufficiency. However, this effect was only shown after 16 weeks of treatment in women with low baseline serum 25(OH)D receiving 25,000 IU, in contrast to women who received 50,000 IU, who started to show a rise in serum 25(OH)D at eight weeks only [48]. Similarly, after 12 weeks of treatment, patients who received standard doses of 800 IU/day and began with sufficient serum baseline 25(OH)D concentrations of 50 nmol/L were unable to achieve mean serum 25(OH)D concentrations of >75 nmol/L [67].

Additionally, Bonjour et al. and Talwar et al. emphasized the significance of baseline 25(OH)D serum concentrations and their impact on vitamin D status. They found that the lower the baseline levels, the higher the response to vitamin D supplementation, showing an inverse relationship between the two [35,47]. Other studies confirmed similar findings [19,68,69]. Many different mechanisms can explain this inverse relation. First, baseline or initial vitamin D status influences the serum 25(OH)D distribution, or the hepatic hydroxylation rate of the cholecalciferol molecule is increased by its product. Another possible mechanism is that vitamin D status could be affected by the strength of the interaction between the vitamin D molecule and its binding protein. The activity of the catabolic vitamin D 24-hydroxylase enzyme may be diminished in response to a sustained decrease in 25(OH)D serum levels [70,71,72]. These findings indicate that basal serum 25(OH)D is a significant predictor of vitamin D status, independent of the dose.

4.4. The Effect of Sun Exposure on Vitamin D Status

Serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly lower in patients exposed to sunlight without additional vitamin D supplementation. Sun exposure combined with vitamin D supplementation, on the other hand, resulted in a significant increase in serum 25(OH)D but only at high doses that ranged between 20,000 IU and 50,000 IU of both vitamin D2 and D3 given monthly for at least three months [48,49]. Both trials involved people of Asian descent who lived in tropical areas. For example, Wicherts et al. demonstrated that sunlight exposure had lower efficacy compared to vitamin D supplementation [73]. In addition, a six-month intervention with sunlight exposure reduced serum 25(OH)D concentrations in young women, and it was inferior to oral vitamin D supplementation or vitamin D-fortified milk in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia [74]. A meta-analysis of seven trials by Moradi et al. [75] confirmed that vitamin D3 significantly increased serum 25(OH)D compared to sun exposure only. Interestingly, Chel et al., on the other hand, found that UV irradiation was as effective as oral vitamin D supplementation in the elderly. However, it is worth mentioning that they used very low doses of 400 IU/day of vitamin D3 [76]. Furthermore, two Australian studies found that as solar UV exposure increased, serum 25(OH)D levels gradually increased, with limited sun exposure being a risk of developing a deficiency [73].

Most studies evaluating vitamin D supplementation have been conducted in countries at higher latitudes. The effect of the seasons on the response to vitamin D supplementation is well established by different studies [77,78,79]. This emphasizes the importance of supplemental vitamin D consumption during the winter season. Fortified milk with vitamin D has been demonstrated to be beneficial in boosting vitamin D status in postmenopausal women who are at increased risk due to insufficient sun exposure and calcium consumption [22,37,38,39,80,81,82]. Interestingly, Talwar et al. [47] empirically noted a pronounced peak in the serum concentration of 25(OH)D from June to September.

4.5. The Effect of Lifestyle Habits and Dietary Intake on Vitamin D Status

Talwar et al. and Reyes-Garcia et al. [46,47] found that age and weight-related variables were not significantly associated with changes in vitamin D serum levels. Mueangpaisarn and Chaiamnuay et al. concluded that body mass index (BMI) is not an independent factor in attaining optimal 25(OH)D levels [43]. However, one trial found that body mass index was a significant predictor of vitamin status and the dose of vitamin D3 [36]. Moreover, Mason et al. [83] found that weight loss through dietary restriction and exercise had no significant effect on serum vitamin D status. Lower 25(OH)D serum concentrations are associated with decreased bioavailability and increased adiposity, implying that weight loss can lead to increased 25(OH)D concentrations via decreased peripheral sequestration in a dose-dependent manner and is unrelated to changes in dietary vitamin D intake.

Manios et al. [40] examined the effects of vitamin D3-enriched cheese on serum 25(OH)D levels in postmenopausal women in the winter season. They found that in addition to the usual dietary intake of around 2 μg/day, a daily dose of 5.7 μg of vitamin D3 significantly raised serum 25(OH) D levels. Johnson et al. [84], in their partially double-blind randomized clinical trial, found that, surprisingly, the daily intake of vitamin D-enriched cheese (15 μg/day) resulted in a significant reduction in serum 25(OH)D of 6 nmol/L. In contrast, the groups that received non-enriched cheese or no cheese had either a significant increase or no change in serum 25(OH)D. These differences could be related to differences in the age of participants, the doses administered, the treatment duration, participants’ compliance with the intervention, and seasonality. Reyes-Garcia et al. [46] showed that 600 IU/day of vitamin D-enriched milk effectively raised serum levels in a large proportion of women.

4.6. Effect of Ethnicity and Genetics

African-American women typically require higher amounts than the recommended upper daily allowance of 2000 IU/day to achieve an optimal serum 25(OH)D concentration of 75 nmol/L, which reflects a dose of 2800 IU/day for those with concentrations >45 nmol/L and 4000 IU/day for those with serum concentrations of <45 nmol/L [32,47]. Although studies on genetic differences with regard to vitamin D supplementations are scarce, one study found that only eleven single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified to be significantly linked to basal serum 25(OH)D in postmenopausal Caucasian women [50].

5. Limitations

The variation in the intervention strategy across all studies in terms of the vitamin D supplementation type, dose, duration, frequency of administration, and serum concentration assay methods has contributed to varying levels of heterogeneity, which may limit the ability to generalize the findings toward general practice guidelines or recommendations. However, the consistency in the results that shows the same factors that influence vitamin D status in postmenopausal women is clear from the evidence compiled from clinical trials. Furthermore, while vitamin D supplementation is important for postmenopausal women due to the effects on bone biomarkers, and while bone health is an essential and significant target for vitamin D, future research may focus on the effects of vitamin D deficiency on a broader range of postmenopausal women’s conditions, given the potential link between vitamin D deficiency and many other conditions.

6. Conclusions

The evidence gathered in this review on the factors influencing vitamin D status was consistent across all trials. A minimum dose of 800 IU/day and a minimum treatment duration of 12 weeks was required to reach serum 25(OH)D levels considered optimal for the health of postmenopausal women. Baseline serum 25(OH)D concentrations, below the sufficient serum baseline 25(OH)D concentrations of 50 nmol/L, were associated with a better response to vitamin D supplementation. To achieve adequate serum 25(OH)D levels, high doses of vitamin D supplementation up to 100,000 IU/week were considered safe and effective. Furthermore, a single 300,000 IU bolus dose was superior to low daily doses. Still, their inability to maintain optimal serum concentrations necessitates the regular use of maintenance doses. Vitamin D3 was superior to vitamin D2 in improving vitamin D status. Active vitamin D metabolite 25(OH)D3 supplementation was more effective than vitamin D3. Vitamin D-fortified foods can be an excellent source of increasing serum 25(OH)D, especially when sun exposure is limited. Although there is no agreement on the optimal doses or concentrations for different patient groups, clinical practice can benefit from the fact that higher doses were always preferred in specific patient groups with large safety margins.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu15030685/s1, Supplementary File.

Author Contributions

M.M.H. and H.Z.H. added to the concept and design of the review; M.M.H. and H.Z.H. contributed to the data extraction, writing, and critical review of the manuscript and data interpretation; H.Z.H. and K.B. provided revisions to the scientific content and significantly contributed to drafting the paper; A.R.A. contributed to the quality assessment of the included records; All authors contributed to critical revision and final approval of the manuscript and agreed to take responsibility for the manuscript’s content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study will be available upon request from (Mohammed M. Hassanein, email: s2163718@siswa.um.edu.my). Data will be available for 1 year from the date the study has ended by email.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

References

- Holick, M.F.; Chen, T.C. Vitamin D deficiency: A worldwide problem with health consequences. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1080S–1086S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Baena, M.T.; Perez-Roncero, G.; Perez-Lopez, F.; Mezones-Holguin, E.; Chedraui, P. Vitamin D, menopause, and aging: Quo vadis? Climacteric 2020, 23, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delle Monache, S.; Di Fulvio, P.; Iannetti, E.; Valerii, L.; Capone, L.; Nespoli, M.; Bologna, M.; Angelucci, A. Body mass index represents a good predictor of vitamin D status in women independently from age. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feghaly, J.; Johnson, P.; Kalhan, A. Vitamin D and obesity in adults: A pathophysiological and clinical update. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2020, 81, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslanca, T.; Korkmaz, H.; Arslanca, S.; Pehlivanoglu, B.; Celikel, O. The Relationship between Vitamin D and Vasomotor Symptoms During the Postmenopausal Period. Clin. Lab. 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riazi, H.; Ghazanfarpour, M.; Taebi, M.; Abdolahian, S. Effect of Vitamin D on the Vaginal Health of Menopausal Women: A Systematic Review. J. Menopausal Med. 2019, 25, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rad, P.; Tadayon, M.; Abbaspour, M.; Latifi, S.; Rashidi, I.; Delaviz, H. The effect of vitamin D on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Donders, G.G.G.; Ruban, K.; Bellen, G.; Grinceviciene, S. Pharmacotherapy for the treatment of vaginal atrophy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2019, 20, 821–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali-Chimeh, F.; Gholamrezaei, A.; Vafa, M.; Nasiri, M.; Abiri, B.; Darooneh, T.; Ozgoli, G. Effect of Vitamin D Therapy on Sexual Function in Women with Sexual Dysfunction and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Kuang, X.; Li, K.; Guo, X.; Deng, Q.; Li, D. Effects of combined calcium and vitamin D supplementation on osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10817–10827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D status: Measurement, interpretation, and clinical application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Scientific Group on the Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis. Prevention and Management of Osteoporosis: Report of a WHO Scientific Group; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, A.C.; Manson, J.; Abrams, S.; Aloia, J.; Brannon, P.; Clinton, S.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Gallagher, J.; Gallo, R.; Jones, G.; et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: What clinicians need to know. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Gordon, C.; Hanley, D.; Heaney, R.; Murad, M.; Weaver, C.; Endocrine, S. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, P.M.; Petak, S.; Binkley, N.; Clarke, B.; Harris, S.; Hurley, D.; Kleerekoper, M.; Lewiecki, E.; Miller, P.; Narula, H.; et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Postmenopausal Osteoporosis—2016. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22 (Suppl. 4), 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips, P.; van Schoor, N.; de Jongh, R. Diet, sun, and lifestyle as determinants of vitamin D status. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1317, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollid, S.T.; Hutchinson, M.; Fuskevag, O.; Joakimsen, R.; Jorde, R. Large Individual Differences in Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Response to Vitamin D Supplementation: Effects of Genetic Factors, Body Mass Index, and Baseline Concentration. Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Horm. Metab. Res. 2016, 48, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, S.J.; Bonjour, J.; Payen, F.; Rousseau, B. Moderate amounts of vitamin D3 in supplements are effective in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D from low baseline levels in adults: A systematic review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2311–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Yalamanchili, V.; Smith, L. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on serum 25(OH)D in thin and obese women. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 136, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P.; Davies, K.; Chen, T.; Holick, M.; Barger-Lux, M. Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, A.K.; Singh, R.; Noymer, A. Vitamin D (25OHD) Serum Seasonality in the United States. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, J.R.; Mott, L.; Barry, E.; Baron, J.; Bostick, R.; Figueiredo, J.; Bresalier, R.; Robertson, D.; Peacock, J. Lifestyle and Other Factors Explain One-Half of the Variability in the Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Response to Cholecalciferol Supplementation in Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2312–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didriksen, A.; Grimnes, G.; Hutchinson, M.; Kjaergaard, M.; Svartberg, J.; Joakimsen, R.; Jorde, R. The serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D response to vitamin D supplementation is related to genetic factors, BMI, and baseline levels. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 169, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Yun, F.; Oczak, M.; Wong, B.; Vieth, R.; Cole, D. Common genetic variants of the vitamin D binding protein (DBP) predict differences in response of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] to vitamin D supplementation. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 42, 1174–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimitphong, H.; Saetung, S.; Chanprasertyotin, S.; Chailurkit, L.; Ongphiphadhanakul, B. Changes in circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D according to vitamin D binding protein genotypes after vitamin D(3) or D(2)supplementation. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, M.; Tran, B.; Armstrong, B.; Baxter, C.; Ebeling, P.; English, D.; Gebski, V.; Hill, C.; Kimlin, M.; Lucas, R.; et al. Environmental, personal, and genetic determinants of response to vitamin D supplementation in older adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E1332–E1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looker, A.C.; Pfeiffer, C.; Lacher, D.; Schleicher, R.; Picciano, M.; Yetley, E. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988–1994 compared with 2000–2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Chandler, T.J.; Cumpston, J.; Li, M.; Page, T.; Welch, M.J.; Cochrane, V.A. Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.3; Cochrane: London, UK, 2022; p. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aloia, J.F.; Talwar, S.; Pollack, S.; Yeh, J. A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in African American women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1618–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, M.; Can, A.; Kizilgul, M.; Beysel, S.; Kan, S.; Caliskan, M.; Demirci, T.; Ozcelik, O.; Ozbek, M.; Cakal, E. The effects of single high-dose or daily low-dosage oral colecalciferol treatment on vitamin D levels and muscle strength in postmenopausal women. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2018, 18, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Stöcklin, E.; Sidelnikov, E.; Willett, W.; Edel, J.; Stähelin, H.; Wolfram, S.; Jetter, A.; Schwager, J.; et al. Oral supplementation with 25(OH)D3 versus vitamin D3: Effects on 25(OH)D levels, lower extremity function, blood pressure, and markers of innate immunity. J. Bone. Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonjour, J.P.; Dontot-Payen, F.; Rouy, E.; Walrand, S.; Rousseau, B. Evolution of Serum 25OHD in Response to Vitamin D(3)-Fortified Yogurts Consumed by Healthy Menopausal Women: A 6-Month Randomized Controlled Trial Assessing the Interactions between Doses, Baseline Vitamin D Status, and Seasonality. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2018, 37, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.C.; Sai, A.; Templin, T., 2nd; Smith, L. Dose response to vitamin D supplementation in postmenopausal women: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 156, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, M.C.; Chan, Y.; Lau, L.; Lau, C.; Chin, Y.; Kuhn-Sherlock, B.; Todd, J.; Schollum, L. Calcium and vitamin D fortified milk reduces bone turnover and improves bone density in postmenopausal women over 1 year. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2785–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.C.; Ha, P.; Todd, J.; Kuhn-Sherlock, B.; Schollum, L.; Ma, J.; Qin, G.; Lau, E. High-calcium, vitamin D fortified milk is effective in improving bone turnover markers and vitamin D status in healthy postmenopausal Chinese women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.C.; Schollum, L.; Kuhn-Sherlock, B.; Hestiantoro, A.; Wijanto, P.; Li-Yu, J.; Agdeppa, I.; Todd, J.; Eastell, R. The effect of a fortified milk drink on vitamin D status and bone turnover in post-menopausal women from South East Asia. Bone 2010, 46, 759–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manios, Y.; Moschonis, G.; Mavrogianni, C.; Heuvel, E.; Singh-Povel, C.; Kiely, M.; Cashman, K. Reduced-fat Gouda-type cheese enriched with vitamin D effectively prevents vitamin D deficiency during winter months in postmenopausal women in Greece. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2367–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastaglia, S.R.; Mautalen, C.; Parisi, M.; Oliveri, B. Vitamin D2 dose required to rapidly increase 25OHD levels in osteoporotic women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minisola, S.; Cianferotti, L.; Biondi, P.; Cipriani, C.; Fossi, C.; Franceschelli, F.; Giusti, F.; Leoncini, G.; Pepe, J.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; et al. Correction of vitamin D status by calcidiol: Pharmacokinetic profile, safety, and biochemical effects on bone and mineral metabolism of daily and weekly dosage regimens. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 3239–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueangpaisarn, P.; Chaiamnuay, S. A randomized double-blinded placebo controlled trial of ergocalciferol 40,000 versus 100,000 IU per week for vitamin D inadequacy in institutionalized postmenopausal women. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Castrillón, J.L.; Dueñas-Laita, A.; Brandi, M.; Jódar, E.; Del Pino-Montes, J.; Quesada-Gómez, J.; Castro, F.C.; Gómez-Alonso, C.; López, L.G.; Martínez, J.O.; et al. Calcifediol is superior to cholecalciferol in improving vitamin D status in postmenopausal women: A randomized trial. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignotti, G.A.P.; Genaro, P.S.; Pinheiro, M.M.; Szejnfeld, V.L.; Martini, L.A. Is a lower dose of vitamin D supplementation enough to increase 25(OH)D status in a sunny country? Eur. J. Nutr. 2010, 49, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Garcia, R.; Mendoza, N.; Palacios, S.; Salas, N.; Quesada-Charneco, M.; Garcia-Martin, A.; Fonolla, J.; Lara-Villoslada, F.; Muñoz-Torres, M. Effects of Daily Intake of Calcium and Vitamin D-Enriched Milk in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind Nutritional Study. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwar, S.A.; Aloia, J.; Pollack, S.; Yeh, J. Dose response to vitamin D supplementation among postmenopausal African American women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, Y.; Hatta, S.; Musa, N.; Rahman, S.; Ratnasingam, J.; Paramasivam, S.; Lim, L.; Ibrahim, L.; Choong, K.; Tan, A.; et al. Maintenance vitamin D3 dosage requirements in Chinese women with post menopausal osteoporosis living in the tropics. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 26, 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Watcharanon, W.; Kaewrudee, S.; Soontrapa, S.; Somboonporn, W.; Srisaenpang, P.; Panpanit, L.; Pongchaiyakul, C. Effects of sunlight exposure and vitamin D supplementation on vitamin D levels in postmenopausal women in rural Thailand: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 40, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Badr, R.; Watson, P.; Ye, A.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, J.; Deng, H.; Recker, R.; et al. SNP rs11185644 of RXRA gene is identified for dose-response variability to vitamin D3 supplementation: A randomized clinical trial. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, M.D.; Binongo, J.; Watson, D.; Alvarez, J.; Lodin, D.; Ziegler, T.; Tangpricha, V. The effect of a single, large bolus of vitamin D in healthy adults over the winter and following year: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjellesen, L.; Hummer, L.; Christiansen, C.; Rodbro, P. Serum concentration of vitamin D metabolites during treatment with vitamin D2 and D3 in normal premenopausal women. Bone Miner 1986, 1, 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, H.M.; Cole, D.; Rubin, L.; Pierratos, A.; Siu, S.; Vieth, R. Evidence that vitamin D3 increases serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D more efficiently than does vitamin D2. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas, L.A.; Hollis, B.; Heaney, R. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5387–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripkovic, L.; Lambert, H.; Hart, K.; Smith, C.; Bucca, G.; Penson, S.; Chope, G.; Hypponen, E.; Berry, J.; Vieth, R.; et al. Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, L.A.; Vieth, R. The case against ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) as a vitamin supplement. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 694–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis, B.W. Comparison of equilibrium and disequilibrium assay conditions for ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol and their major metabolites. J. Steroid. Biochem. 1984, 21, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmberg, I.; Berlin, T.; Ewerth, S.; Bjorkhem, I. 25-Hydroxylase activity in subcellular fractions from human liver. Evidence for different rates of mitochondrial hydroxylation of vitamin D2 and D3. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1986, 46, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamp, T.C. Intestinal absorption of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol. Lancet 1974, 2, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.G., Jr.; Rojanasathit, S. Acute administration of 25-hydroxycholecalciferol in man. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1976, 42, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barger-Lux, M.J.; Heaney, R.; Dowell, S.; Chen, T.; Holick, M. Vitamin D and its major metabolites: Serum levels after graded oral dosing in healthy men. Osteoporos. Int. 1998, 8, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.M.; Peacock, M.; Storer, J.; Davies, A.; Brown, W.; Nordin, B. Calcium malabsorption in the elderly: The effect of treatment with oral 25-hydroxyvitamin D3. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1983, 13, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.J.; Halstead, L.; Teitelbaum, S.; Hahn, B. Altered mineral metabolism in glucocorticoid-induced osteopenia. Effect of 25-hydroxyvitamin D administration. J. Clin. Investig. 1979, 64, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, M.; Liu, G.; Carey, M.; McClintock, R.; Ambrosius, W.; Hui, S.; Johnston, C. Effect of calcium or 25OH vitamin D3 dietary supplementation on bone loss at the hip in men and women over the age of 60. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 3011–3019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sosa, M.; Lainez, P.; Arbelo, A.; Navarro, M. The effect of 25-dihydroxyvitamin D on the bone mineral metabolism of elderly women with hip fracture. Rheumatology 2000, 39, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, T.C.; Haddad, J.G.; Twigg, C.A. Comparison of oral 25-hydroxycholecalciferol, vitamin D, and ultraviolet light as determinants of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Lancet 1977, 1, 1341–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broe, K.E.; Chen, T.; Weinberg, J.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Holick, M.; Kiel, D. A higher dose of vitamin d reduces the risk of falls in nursing home residents: A randomized, multiple-dose study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2007, 55, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljakainen, H.T.; Palssa, A.; Karkkainen, M.; Jakobsen, J.; Lamberg-Allardt, C. How much vitamin D3 do the elderly need? J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2006, 25, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, L.J.; Seamans, K.; Cashman, K.; Kiely, M. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of vitamin D food fortification. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.C.Y.; Nicholls, H.; Piec, I.; Washbourne, C.; Dutton, J.; Jackson, S.; Greeves, J.; Fraser, W. Reference intervals for serum 24,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and the ratio with 25-hydroxyvitamin D established using a newly developed LC-MS/MS method. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 46, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Chun, R.; Lisse, T.; Garcia, A.; Xu, J.; Adams, J.; Hewison, M. Vitamin D and alternative splicing of RNA. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 148, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicherts, I.S.; Boeke, A.; van der Meer, I.; van Schoor, N.; Knol, D.; Lips, P. Sunlight exposure or vitamin D supplementation for vitamin D-deficient non-western immigrants: A randomized clinical trial. Osteoporos. Int. 2011, 22, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Daghri, N.M.; Abd-Alrahman, S.; Panigrahy, A.; Al-Saleh, Y.; Aljohani, N.; Al-Attas, O.; Khattak, M.; Alokail, M. Efficacy of Vitamin D interventional strategies in saudi children and adults. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 180, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, S.; Shahdadian, F.; Mohammadi, H.; Rouhani, M. A comparison of the effect of supplementation and sunlight exposure on serum vitamin D and parathyroid hormone: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chel, V.G.; Ooms, M.; Popp-Snijders, C.; Pavel, S.; Schothorst, A.; Meulemans, C.; Lips, P. Ultraviolet irradiation corrects vitamin D deficiency and suppresses secondary hyperparathyroidism in the elderly. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1998, 13, 1238–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieth, R.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.; Boucher, B.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Garland, C.; Heaney, R.; Holick, M.; Hollis, B.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; McGrath, J.; et al. The urgent need to recommend an intake of vitamin D that is effective. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, D.P.; Doll, R.; Khaw, K. Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: Randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ 2003, 326, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapuy, M.C.; Pamphile, R.; Paris, E.; Kempf, C.; Schlichting, M.; Arnaud, S.; Garnero, P.; Meunier, P. Combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in elderly women: Confirmation of reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hip fracture risk: The Decalyos II study. Osteoporos. Int. 2002, 13, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Chen, T.; Lu, Z.; Sauter, E. Vitamin D and skin physiology: A D-lightful story. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007, 22 (Suppl. 2), V28–V33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, J.; Rapp, K.; Denkinger, M.; Nagel, G.; Nikolaus, T.; Peter, R.; Koenig, W.; Bohm, B.; Rothenbacher, D. Seasonality of vitamin D status in older people in Southern Germany: Implications for assessment. Age Ageing 2013, 42, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, H.M. Contributions of sunlight and diet to vitamin D status. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 92, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, C.; Xiao, L.; Imayama, I.; Duggan, C.; Bain, C.; Foster-Schubert, K.; Kong, A.; Campbell, K.; Wang, C.; Neuhouser, M.; et al. Effects of weight loss on serum vitamin D in postmenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L.; Mistry, V.; Vukovich, M.; Hogie-Lorenzen, T.; Hollis, B.; Specker, B. Bioavailability of vitamin D from fortified process cheese and effects on vitamin D status in the elderly. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2295–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).