Virtual Pedagogy and Care: Systematic Review on Educational Innovation with Mobile Applications for the Development of Healthy Habits in the Adolescent Population

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction

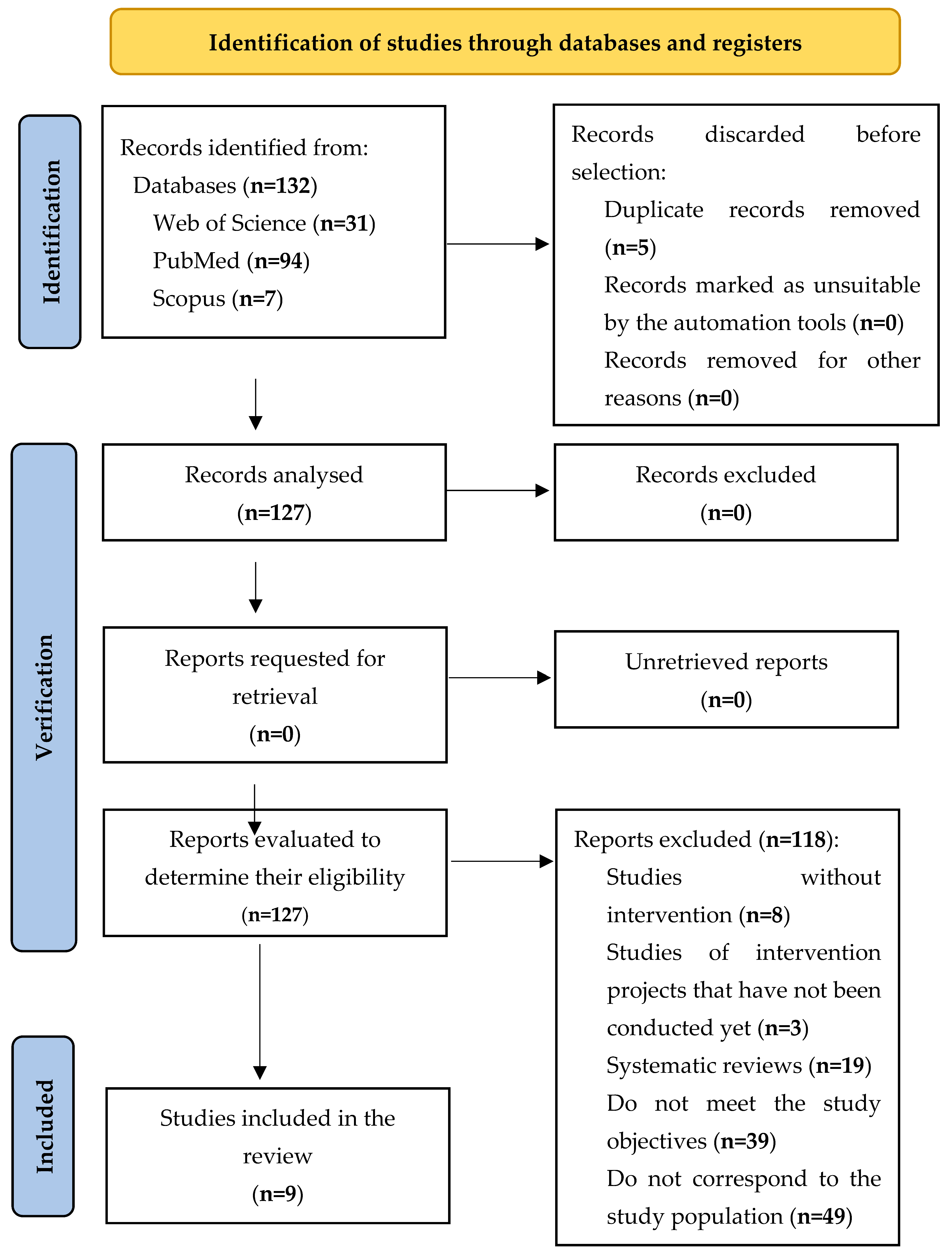

2.5. Presentation of the Results: Adherence to Quality Initiatives (PRISMA)

2.6. Quality Evaluation

| Articles | Components | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Global Score | |

| Steinberg et al. [18] | S | W | W | W | S | S | W |

| Hogsdal et al. [19] | M | W | S | W | S | S | W |

| Nagamitsu et al. [14] | M | S | S | W | S | S | M |

| Villasana et al. [20] | W | W | M | W | M | W | W |

| Caón et al. [15] | S | S | M | W | S | M | M |

| Thornton et al. [21] | S | W | M | W | M | M | W |

| Müssener et al. [22] | W | W | W | W | M | S | W |

| Lei et al. [16] | S | M | M | W | M | S | M |

| Vidmar et al. [17] | M | S | M | W | S | S | M |

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Studies and Data Extraction Process

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies: Results Synthesis

3.3. Association between the Different Mobile Applications with Didactic Strategies for the Promotion of Healthy Habits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gore, F.M.; Bloem, P.J.; Patton, G.C.; Ferguson, J.; Joseph, V.; Coffey, C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Mathers, C.D. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalonde, M. New perspective on the health of Canadians: 28 years later. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2002, 12, 149–152. Available online: https://www.scielosp.org/article/rpsp/2002.v12n3/149-152/ (accessed on 12 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Guilar, M.E. Las ideas de Bruner: De la revolución cognitiva a la revolución cultural. Educere 2009, 13, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Carta de Ottawa para la Promoción de la Salud. Primera Conferencia Internacional Sobre la Promoción de la Salud: Hacia un Nuevo Concepto de la Salud Pública. Ottawa: Salud y Bienestar Social de Canadá, Asociación Canadiense de Salud Pública. 1986. Available online: https://isg.org.ar/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Carta-Ottawa.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Simmonds, M.; Llewellyn, A.; Owen, C.G.; Woolacott, N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.D.; Patton, G.; Stockings, E.; Weier, M.; Lynskey, M.; Morley, K.I.; Degenhardt, L. Why young people’s substance use matters for global health. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockings, E.; Hall, W.D.; Lynskey, M.; Morley, K.I.; Reavley, N.; Strang, J.; Patton, G.; Degenhardt, L. Prevention, early intervention, harm reduction, and treatment of substance use in young people. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, G.C.; Coffey, C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Viner, R.M.; Haller, D.; Bose, K.; Vos, T.; Ferguson, J.; Mathers, C.D. Global patterns of mortality in young people: A systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009, 374, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.F.; Fagan, A.A.; Gavin, L.E.; Greenberg, M.T.; Irwin, C.E.; Ross, D.A.; Shek, D.T. Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. Lancet 2012, 379, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, D.; Koketsu, J.S. Activities of daily living. Pedrettis Occup. Ther. Pract. Ski. Phys. Dysfunct. 2013, 7, 157–232. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Elementos de informe preferidos para los protocolos de revisión sistemática y metanálisis (PRISMA-P) Declaración de 2015. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. Available online: https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1/ (accessed on 27 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomás, B.H.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. Un proceso para revisar sistemáticamente la literatura: Proporcionar evidencia de investigación para intervenciones de enfermería en salud pública. Cosmovisiones Evid. Enfermería Basada 2004, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nagamitsu, S.; Kanie, A.; Sakashita, K.; Sakuta, R.; Okada, A.; Matsuura, K.; Ito, M.; Katayanagi, A.; Katayama, T.; Otani, R.; et al. Intervenciones de promoción de la salud de los adolescentes mediante visitas de bienestar y una aplicación de terapia conductual cognitiva para teléfonos inteligentes: Ensayo controlado aleatorizado. JMIR Health Uhealth 2022, 10, e34154. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35604760/ (accessed on 23 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Caon, M.; Prinelli, F.; Angelini, L.; Carrino, S.; Mugellini, E.; Orte, S.; Serrano, J.C.E.; Atkinson, S.; Martin, A.; Adorni, F. PEGASO e-Diary: Compromiso del usuario y cambio de comportamiento dietético de un registro móvil de alimentos para adolescentes. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 727480. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35369096/ (accessed on 27 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Kumar, S.; Lee, A.T.; Scott, C.G.; Lerman, A.; Lerman, L.O.; Senecal, C.G.; Lin, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Efectividad de un Programa de Adelgazamiento con Salud Digital en Adolescentes y Preadolescentes. Child Obes. 2021, 17, 311–321. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33826417/ (accessed on 26 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Vidmar, A.P.; Pretlow, R.; Borzutzky, C.; Wee, C.P.; Fox, D.S.; Fink, C.; Mittelman, S.D. Una intervención de pérdida de peso de salud móvil basada en un modelo de adicción en adolescentes con obesidad. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 14, e12464. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30117309/ (accessed on 18 January 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, A.; Griffin-Tomas, M.; Abu-Odeh, D.; Whitten, A. Evaluación de una aplicación de teléfono móvil para brindar información sobre salud sexual y reproductiva a los adolescentes, ciudad de Nueva York, 2013–2016. Public Health Rep. 2018, 133, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogsdal, H.; Káiser, S.; Kyrrestad, H. Evaluación de los adolescentes de dos aplicaciones móviles que promueven la salud mental: Resultados de dos encuestas de usuarios. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e40773. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36607734/ (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Villasana, M.V.; Pires, I.M.; Sá, J.; Garcia, N.M.; Teixeira, M.C.; Zdravevski, E.; Chorbev, I.; Lameski, P. Promoción de estilos de vida saludables para adolescentes con dispositivos móviles: Un estudio de caso en Portugal. Healthcare 2020, 8, 315. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32887251/ (accessed on 13 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Thornton, L.; Gardner, L.A.; Osman, B.; Green, O.; Champion, K.E.; Bryant, Z.; Teesson, M.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Chapman, C. Una aplicación móvil de autocontrol y cambio de comportamiento de salud múltiple para adolescentes: Estudio de desarrollo y usabilidad de la aplicación Health4Life. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e25513. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33843590/ (accessed on 29 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Müssener, U.; Thomas, K.; Linderoth, C.; Löf, M.; Åsberg, K.; Henriksson, P.; Bendtsen, M. Desarrollo de una intervención dirigida a múltiples comportamientos de salud entre estudiantes de secundaria: Estudio de diseño participativo utilizando evaluación heurística y pruebas de usabilidad. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e17999. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33118942/ (accessed on 25 January 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Rincón, E.H.; Barbosa, S.D.; Valdivieso, A.; Cruz, P.A.; Forero, J.L. Aplicaciones móviles para la prevención del suicidio en adolescentes y adultos jóvenes. Rev. Cuba. Inf. Cienc. Salud ACIMED 2020, 31, 1–20. Available online: https://www.medigraphic.com/cgi-bin/new/resumen.cgi?IDARTICULO=101296 (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Pérez Márquez, Y.; Casillas, L.M.; Juárez, A.; González-forteza, C.; Garbus, P. Propuesta de diseño de una aplicación móvil psicoeducativa de Salud Mental para adolescentes. XIII Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología. XXVIII Jornadas de Investigación. XVII Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. III Encuentro de Investigación de Terapia Ocupacional. III Encuentro de Musicoterapia. Facultad de Psicología—Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. 2021. Available online: https://www.aacademica.org/000-012/958 (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Anthes, E. Salud mental: Hay una aplicación para eso. Nature 2016, 532, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, T.; Barker, M.; Jacob, C.; Morrison, L.; Lawrence, W.; Strömmer, S.; Vogel, C.; WoodsTownsend, K.; Farrell, D.; Inskip, H.; et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviours of adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 61, 669–677. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/28822682 (accessed on 5 January 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, C.L. Enfermería: Profesión llamada a mantener y promover la salud mental desde el primer nivel de atención. Rev. Cúpula 2019, 33, 26–32. Available online: https://www.binasss.sa.cr/bibliotecas/bhp/cupula/v33n1/art02.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Roldán, V.P.; Pérez Guzmán, K.G.; Rodríguez Morales, B.S.; Merchán, M.F.; Acero, J.D.; Carvajal, J.A. Diseño e implementación de una aplicación web para el apoyo a clases de educación sexual en colegios. [Proyecto de diseño] Departamento de Ingeniería Biomédica de la Universidad de los Andes. 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.uniandes.edu.co/handle/1992/58342 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Rodrigo-Sanjoaquín, J.; Sevil-Serrano, J.; Julián Clemente, J.A.; Generelo, E.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Implementación de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación en la Promoción de Hábitos Saludables; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Zaragoza: Zaragoza, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/79600 (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Durán Vinagre, M.A.; Leador, V.M.; Sánchez Herrera, S.; Feu, S. Motivación y TIC como reguladores de la actividad física en adolescentes: Una revisión sistemática. Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Física Deporte Recreación 2021, 42, 785–797. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7986377 (accessed on 24 January 2023).

- Ramírez-Vélez, R.; Triana-Reina, H.R.; Carrillo, H.A.; Ramos-Sepúlveda, J.A. Percepción de barreras para la práctica de la actividad física y obesidad abdominal en universitarios de Colombia. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 1317–1323. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?pid=S0212-16112016000600010&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en (accessed on 28 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- Serna, S.; Pardo, C. Diseño de interfaces en aplicaciones móviles. Grupo Editorial RA-MA. 2016. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=SI-fDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Dise%C3%B1o+de+interfaces+en+aplicaciones+m%C3%B3viles.+Grupo+Editorial+RA-MA&ots=bKh1NSq7qu&sig=1dw912fa6C3UzzLSn1I62iEqFZM#v=onepage&q=Dise%C3%B1o%20de%20interfaces%20en%20aplicaciones%20m%C3%B3viles.%20Grupo%20Editorial%20RA-MA&f=false (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- San Mauro, I.; González Fernández, M.; Collado, L. Aplicaciones móviles en nutrición, dietética y hábitos saludables: Análisis y consecuencia de una tendencia a la alza. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 30, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chóliz, M.; Villanueva, V.; Chóliz, M.C. Ellas, ellos y su móvil: Uso, abuso (¿y dependencia?) del teléfono móvil en la adolescencia. Rev. Española Drogodepend. 2009, 34, 74–78. Available online: https://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/22402 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

| Author (Year) Country [Reference] | Study Design | Comparisons | Study Objectives | Participants | Measurement Variables (Scale Used) | Interventions | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steinberg et al. (2018) USA [18] | Analytical, observational study | A single study group (the entire adolescent population of NYC that voluntarily downloaded the Teens app in NYC) | To promote sex and reproductive health among adolescents aged 12–19 years in New York | n = 22.137 | Sex health services (birth control or gynaecological services, STD tests and treatment, pregnancy tests, abortion services, HIV tests, golden star service, mental health counselling and lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender/queer (LGBTQ)–specific service), and different birth-control methods (condom, oral contraceptive pill, emergency contraceptives, injectable contraceptives, women’s condom, hormonal intrauterine device, copper intrauterine device, contraceptive implant, vaginal ring and birth-control patch) | This application has 3 main sections: Where to go, what to obtain and what to expect. Through different means, the application was disseminated among the study population, and the number of downloads was analysed, as well as the different sections used. | The results obtained in this study indicate that the application helped the adolescents to discover and access a wide range of sex health services, including the least used contraceptives. Therefore, the evaluation of the Teens mobile application in NYC suggests that mobile applications with search functionality are an effective way of providing information about sex health services to adolescents. |

| Hogsdal et al. (2023) Norway [19] | Cross-sectional study | Two groups: —One group of adolescents tried the Opp application (n = 27) —Another group of adolescents tried the NettOpp application (n = 15) | To investigate how adolescents evaluate the usability, quality and potential attainment of goals of Opp and NettOpp. | n = 42 | Usability of the application (SUS scale), quality of the applications and attainment of the goals (knowledge, attitudes and intention to change the behaviour of the adolescents) (MARS scale). | The participants used the applications for a period of 3 weeks, and then they completed 2 cross-sectional questionnaires for users. The adolescents who tried Opp completed an online questionnaire, whereas those who tried NettOpp completed a paper questionnaire. | This study indicates that Opp and NettOpp have good usability and that the adolescents were satisfied with both applications. Most of the participants who evaluated Opp considered that the application would increase the user’s knowledge about mental health and help young people to cope with stress and difficult emotions and situations. Most of the participants who evaluated NettOpp stated that the application would raise awareness and knowledge about cyberbullying, change the attitudes toward cyberbullying and motivate them to address cyberbullying. |

| Nagamitsu et al. (2022) Japan [14] | Controlled, randomised, multi-institutional, prospective trial | -Two intervention groups: 1. WCV group (n = 66) 2. WCV + CBT application group (n = 66) -One control group without intervention (n = 70) | To test the efficacy of two interventions of health promotion in adolescents: a well-care visit (WCV) with an interview for risk evaluation, counselling and self-control, with a behavioural cognitive therapy (BCT) application for smart phones with the CBT application. | n = 202 | Depression (DSRS-C scale), adolescent health promotion behaviours (AHP-SF scale), positive and negative global attitudes toward oneself (RSES scale), health-related quality of life (PedsQL scale), suicidal ideation (PHQ-9 scale), emotional intelligence traits—Short form for adolescents (TEIQue-ASF scale). | The participants of all groups were asked to complete a questionnaire that included several outcome measures in four time points: at the beginning and 1, 2 and 4 months after the beginning. For the group that only received the intervention with WCV, clinical data were gathered, and a physical examination was conducted in the first visit, and they received educational leaflets about health promotion aspects. In the next visits to the research centre, they completed an interview, and training sessions were also carried out. For the group that received the intervention with CBT, a programme was applied with a session of psychoeducation and another session of self-control. In this group, the participants had 10 different scenarios in the mobile application that taught different aspect about how feelings are associated with thoughts and actions. | There was significantly less suicidal ideation in the intervention groups. There was also a significant increase in the scores of the health promotion scale at 4 months of follow up among the secondary education students in the WCV group. Moreover, the CBT application was significantly effective in terms of obtaining self-control skills and reducing depression. |

| Villasana et al. (2020) Portugal [20] | Longitudinal, quasi-experimental design | The intervention was conducted in an experimental group, without a control group. | This study analysed the evolution of physical activity and nutrition habits of the adolescents involved in the study with a mobile application. | n = 7 | Habits related to physical activity, food consumption and level of physical activity throughout the intervention (information gathering through questionnaires developed by the author). | The participants used the mobile application for five weeks, during which they were given 18 curiosities and 10 suggestions about nutrition and physical activity, as well as six challenges about the number of steps they had to take and calories that they had to burn. The mobile application was also used to administer four questionnaires related to the available advice and curiosities. During the study, the participants responded to four weekly questionnaires about the advice and curiosities that are provided by the mobile application. | The study demonstrated that a mobile application could be a complement for the promotion of healthy lifestyles, fostering the adoption of a healthy diet, as well as good physical activity habits. |

| Caón et al. (2022) England (UK), Scotland (UK), Lombardía (Italy) and Catalonia (Spain) [15] | Cross-sectional, analytical study | —One intervention group (n = 357) —One control group (n = 193) | To describe the methodology to implement the mobile register of foods of e-Diary Pegaso, evaluate its capacity to promote healthy eating habits, and assess the factors associated with its use and commitment. | n = 550 | Evaluation based on diet and 6 target eating behaviours (DTB) related to the consumption of: fruit; vegetables; breakfast; sugary drinks; fast food; and sandwiches, continuous frequency of use in weeks (KIDMED), BMI, self-perceived health state (SPHS), socioeconomic level (FAS) and motivation to use the application (PCS). | The study scenarios selected were 12 secondary schools of four European places. A mobile phone was given with an application to provide proactive health promotion to all participants. For 6 months, the electronic diary followed-up on the eating habits of the users. | It was observed that, in those participants who were strongly committed to the e-Diary Pegaso application, there was an association with better eating behaviours: greater consumption of fruits and vegetables and lower breakfast skipping. |

| Thornton et al. (2021) Australia [21] | Controlled, randomised trial | A single group | To describe the development, usability and acceptability of the Health4Life application, which is an application of self-control for smart phones aimed at adolescents. | n = 232 | Demographic characteristics (age, sex and post code) and 6 main lifestyle behaviours (bad diet, physical inactivity, smoking, alcohol consumption, sedentary recreational screen time, and lack of or excess sleep) | The participants were granted access to the Health4Life application, in which they had to record their health behaviours. Additionally, they had to complete an online questionnaire that evaluated the application, in order to generate information about its usability and acceptability. | In general, the students gave a favourable score to the Health4Life application. They considered it to be highly acceptable and usable, and they believed that it had the potential to efficiently and effectively modify important risk factors for chronic diseases among young people. |

| Müssener et al. (2020) Sweden [22] | Cross-sectional study | A single intervention group | To investigate the usability of an intervention of mHealth (LIFE4YOUth). | n = 5 | Heuristic evaluation (visibility of the system’s state; similarities between the system and the real world; control and freedom of the user; consistency and standards; prevention of errors; identification instead of recovery; flexibility and efficiency of use; aesthetic minimalist design; helping the users to recognise, diagnose and recover from mistakes; help and documentation). Usability tests (see home page and explain what you think about the design; Where can you find support to drink less alcohol?; Record how much you drink; How to search for information about physical exercise activities; How to find a physical exercise activity and its participation level?; Describe how to set a goal for eating habits; What information can you find in the “Risks” section within the Diet module? Is it adequately visible in general?; Give us your opinion on the information provided in the first page of the Smoking module; How can you know more about the benefits of quitting smoking?). | All participants were invited to a brief training session (approximately 45 min), which was conducted by a research assistant (CL), in order to be briefed on the fundamental principles of heuristic evaluation and learn to use heuristics to evaluate the intervention. The participants were sent a link to a high-fidelity prototype of the intervention, included in the home page of the real software, the menu page and the 4 intervention modules (alcohol consumption, smoking, physical activity and diet). Each participant was asked to identify usability problems independently in a certain protocol. The participants were asked to identify a problem, describe it, identify the relevant heuristics for the problem and give it a severity score. | The usability tests showed that the design (aesthetics and clarity) and content (quality and quantity) enabled the usability of the application. However, the deficient functionality was considered an important barrier. One of the five participants gave a low score to the LIFE4YOUth intervention, two of them gave it an average score, and the other two evaluated it as good, according to the System Usability Scale. The mHealth intervention did not offer optimal functions, thus it entails the risk that students may stop using it. To sum up, it is fundamental to optimise the usability of the mobile health interventions of this application, in order to be applied with more satisfactory results. |

| Lei et al. (2021) Continental China [16] | Observational, retrospective analysis | A single group | To evaluate the efficacy of a digital health platform for weight loss using a mobile application (MetaWell), a wireless scale and calorie restriction with nutritional supplements in adolescents. | n = 2825 | Age, sex, weight, percentile and BMI | The participants used a remote weight-loss programme that combined the use of a mobile application “MetaWell”, frequent self-weighing and calorie restriction with meal replacements. The changes in body weight were evaluated at 42, 60, 90 and 120 days using different metrics, including absolute body weight, BMI and Z score of BMI. | This study shows that the digital, remote weight-loss programme is effective at facilitating weight loss in overweight and obese adolescents in the short and medium term, since the participants achieved a clinically significant weight loss through this programme. Moreover, greater weight loss was observed in the older participants, in those who weighed themselves more frequently, and in those who had high baseline BMI percentiles. |

| Vidmar et al. (2018) USA [17] | Controlled, randomised trial | Two groups: One experimental group, who received intervention with App (W8Loss2Go©)[17] (n = 18). One control group, who received intervention in a clinic with conventional treatments (n = 17) | To evaluate whether an intervention with a mobile application of healthy habits could be a feasible and effective approach for adolescent patients with problems related to bad eating habits. | n = 35 | Sociodemographic variables (sex, age, race, ethnicity); addictive behaviour (YFAS-c); abstinence from “problematic foods”; removal of elaborate meals; reduction in the amount of food in the meals; height; weight; addictive eating habits | The control group had a multidisciplinary intervention with conventional treatments. The interventions were carried out in monthly visits to the clinic for a period of 6 months. The individualised objectives of behavioural change were aimed at healthy eating, physical activity, emotional well-being and family support, which were followed up in the subsequent monthly visits. Another experimental group received an intervention with the W8Loss2Go© application. The intervention included two visits to the clinic at 3 and 6 months (45 min per visit), text messages 5 days per week, and phone sessions every week (15 min × 24 sessions = 360 min). The intervention was focused on three characteristics of the addictive eating behaviour: (i) gradual removal of problematic foods identified by the participant; (ii) staggered removal of sandwiches between meals; and (iii) abstinence from excessive amounts of foods in the meals. | The group that received the intervention with the mHealth App “W8Loss2Go” [17] obtained better results in the improvement of BMI and in the effective completion of the therapeutic treatment, compared to the group that received the intervention in the clinic with conventional treatments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arana-Álvarez, C.; Gómez-Asencio, D.; Gago-Valiente, F.-J.; Cabrera-Arana, Y.; Merino-Godoy, M.-d.-l.-Á.; Moreno-Sánchez, E. Virtual Pedagogy and Care: Systematic Review on Educational Innovation with Mobile Applications for the Development of Healthy Habits in the Adolescent Population. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183966

Arana-Álvarez C, Gómez-Asencio D, Gago-Valiente F-J, Cabrera-Arana Y, Merino-Godoy M-d-l-Á, Moreno-Sánchez E. Virtual Pedagogy and Care: Systematic Review on Educational Innovation with Mobile Applications for the Development of Healthy Habits in the Adolescent Population. Nutrients. 2023; 15(18):3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183966

Chicago/Turabian StyleArana-Álvarez, Cristina, David Gómez-Asencio, Francisco-Javier Gago-Valiente, Yeray Cabrera-Arana, María-de-los-Ángeles Merino-Godoy, and Emilia Moreno-Sánchez. 2023. "Virtual Pedagogy and Care: Systematic Review on Educational Innovation with Mobile Applications for the Development of Healthy Habits in the Adolescent Population" Nutrients 15, no. 18: 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183966

APA StyleArana-Álvarez, C., Gómez-Asencio, D., Gago-Valiente, F.-J., Cabrera-Arana, Y., Merino-Godoy, M.-d.-l.-Á., & Moreno-Sánchez, E. (2023). Virtual Pedagogy and Care: Systematic Review on Educational Innovation with Mobile Applications for the Development of Healthy Habits in the Adolescent Population. Nutrients, 15(18), 3966. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183966