In Which Situations Do We Eat? A Diary Study on Eating Situations and Situational Stability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

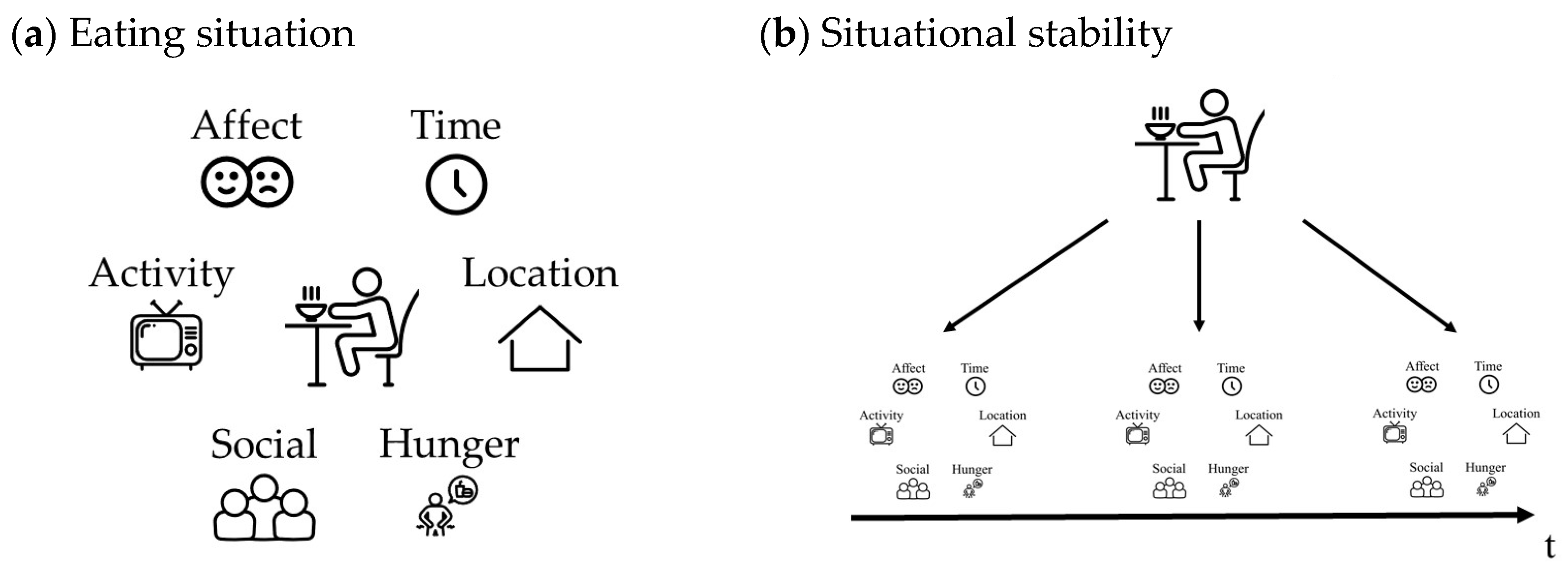

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. RO1: Eating Situations for Breakfast, Lunch, and Dinner

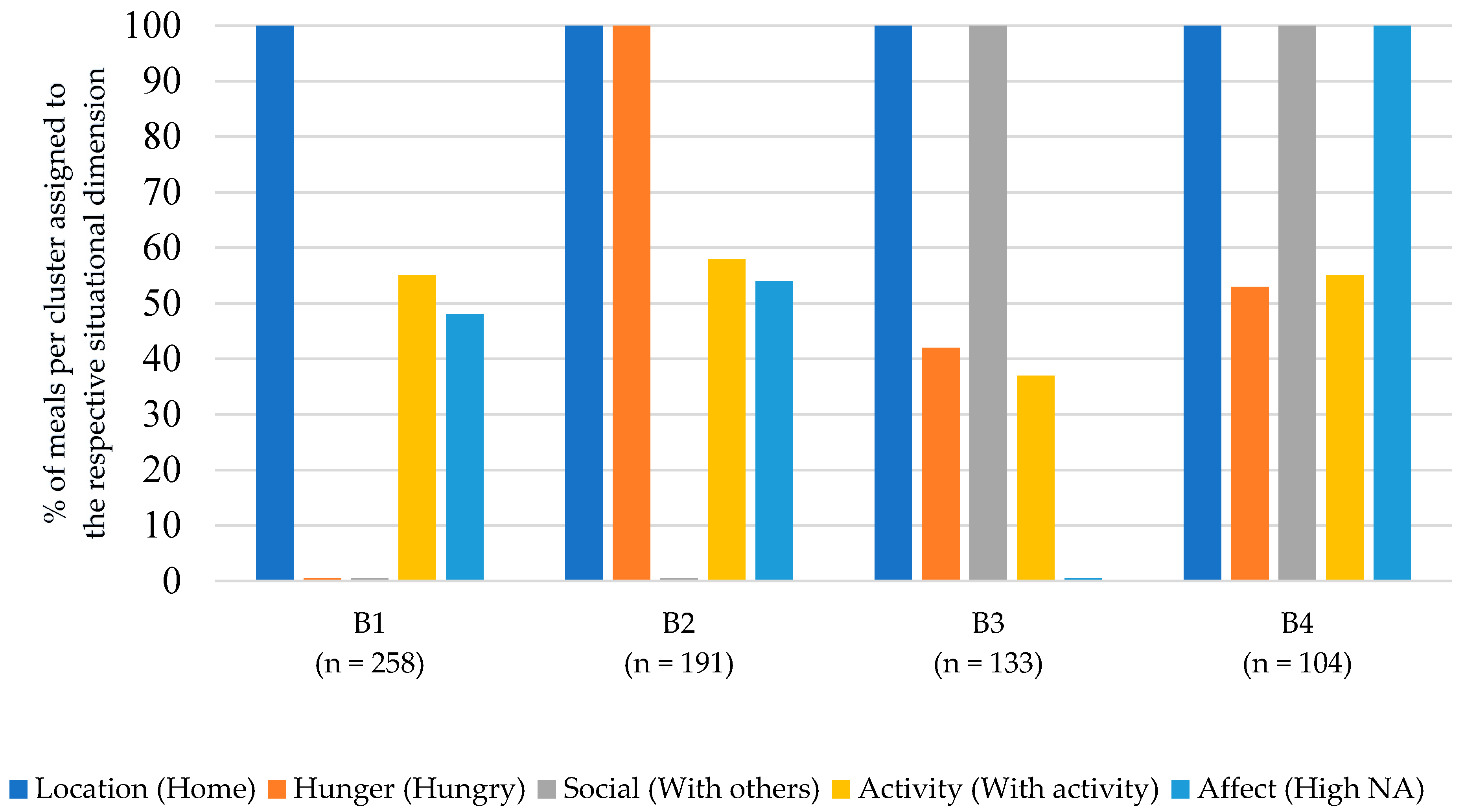

3.1.1. Breakfast

3.1.2. Lunch

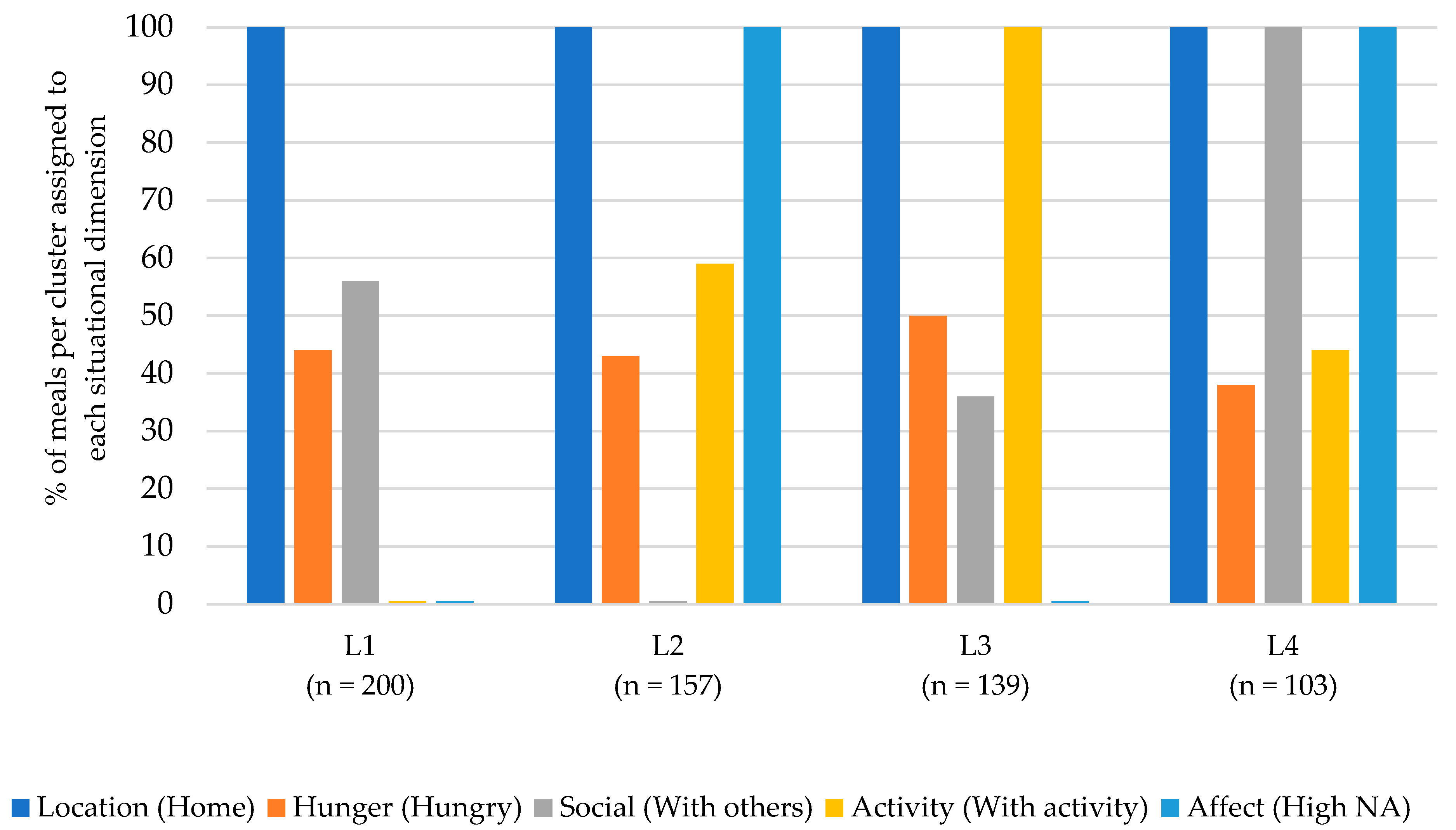

3.1.3. Dinner

3.2. RO2: Situational Stability and Its Association with Socio-Demographic Characteristics

4. Discussion

4.1. Eating Situations as Combinations of Situational Dimensions

4.1.1. Breakfast

4.1.2. Lunch

4.1.3. Dinner

4.1.4. Summary

4.2. Stability of Eating Situations within and between Individuals

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogni, C.A.; Falk, L.W.; Madore, E.; Blake, C.E.; Jastran, M.; Sobal, J.; Devine, C.M. Dimensions of everyday eating and drinking episodes. Appetite 2007, 48, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastran, M.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J.; Blake, C.; Devine, C.M. Eating routines. Embedded, value based, modifiable, and reflective. Appetite 2009, 52, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wansink, B.; Painter, J.E.; North, J. Bottomless bowls: Why visual cues of portion size may influence intake. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diliberti, N.; Bordi, P.L.; Conklin, M.T.; Roe, L.S.; Rolls, B.J. Increased portion size leads to increased energy intake in a restaurant meal. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Duffey, K.J. Does hungesr and satiety drive eating anymore? Increasing eating occasions and decreasing time between eating occasions in the United States. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffey, K.J.; Popkin, B.M. Energy density, portion size, and eating occasions: Contributions to increased energy intake in the United States, 1977–2006. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, e1001050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosburger, R.; Barbosa, C.L.; Haftenberger, M.; Brettschneider, A.-K.; Lehmann, F.; Kroke, A.; Mensink, G.B.M. Fast food consumption among 12- to 17-year-olds in Germany—Results of EsKiMo II. J. Health Monit. 2020, 5, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, F.; Dello Russo, M.; Formisano, A.; de Henauw, S.; Hebestreit, A.; Hunsberger, M.; Krogh, V.; Intemann, T.; Lissner, L.; Molnar, D.; et al. Ultra-processed foods consumption and diet quality of European children, adolescents and adults: Results from the I.Family study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3031–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevijvere, S.; de Ridder, K.; Fiolet, T.; Bel, S.; Tafforeau, J. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and diet quality among children, adolescents and adults in Belgium. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 3267–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauber, F.; Da Costa Louzada, M.L.; Steele, E.M.; Millett, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases-Related Dietary Nutrient Profile in the UK (2008–2014). Nutrients 2018, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verger, E.O.; Le Port, A.; Borderon, A.; Bourbon, G.; Moursi, M.; Savy, M.; Mariotti, F.; Martin-Prevel, Y. Dietary Diversity Indicators and Their Associations with Dietary Adequacy and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Scoping Review. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, M.M.; Davis, J.A.; Beattie, S.; Gómez-Donoso, C.; Loughman, A.; O’Neil, A.; Jacka, F.; Berk, M.; Page, R.; Marx, W.; et al. Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlatevska, N.; Dubelaar, C.; Holden, S.S. Sizing up the Effect of Portion Size on Consumption: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacremont, C.; Sester, C. Context in food behavior and product experience—A review. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2019, 27, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, W. Breaking bad habits: A dynamical perspective on habit formation and change. In Human Decision Making and Environmental Perception: Understanding and Assisting Human Decision Making in Real-Life Settings: Liber Amicorum for Charles Vlek; Hendrickx, L., Jager, W., Steg, L., Eds.; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2003; ISBN 9789036718998. [Google Scholar]

- Laffan, K. Counting Contexts that Count: An Exploration of the Contextual Correlates of Meat Consumption in Three Western European Countries; [discussion paper]; 2021; Available online: https://www.ucd.ie/geary/static/publications/workingpapers/gearywp202113.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Onita, B.M.; Azeredo, C.M.; Jaime, P.C.; Levy, R.B.; Rauber, F. Eating context and its association with ultra-processed food consumption by British children. Appetite 2021, 157, 105007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van’t Riet, J.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Dagevos, H.; de Bruijn, G.-J. The importance of habits in eating behaviour. An overview and recommendations for future research. Appetite 2011, 57, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, L.W.; Bisogni, C.A.; Sobal, J. Personal, Social, and Situational Influences Associated with Dietary Experiences of Participants in an Intensive Heart Program. J. Nutr. Educ. 2000, 32, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiselman, H.L.; Johnson, J.L.; Reeve, W.; Crouch, J.E. Demonstrations of the influence of the eating environment on food acceptance. Appetite 2000, 35, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, D.R.; Villinger, K.; Blumenschein, M.; König, L.M.; Ziesemer, K.; Sproesser, G.; Schupp, H.T.; Renner, B. Why We Eat What We Eat: Assessing Dispositional and In-the-Moment Eating Motives by Using Ecological Momentary Assessment. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e13191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Blissett, J.; Higgs, S. Social influences on eating: Implications for nutritional interventions. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2013, 26, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliston, K.G.; Ferguson, S.G.; Schüz, N.; Schüz, B. Situational cues and momentary food environment predict everyday eating behavior in adults with overweight and obesity. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Laska, M.N.; Story, M. Young adults and eating away from home: Associations with dietary intake patterns and weight status differ by choice of restaurant. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvo, P.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Matacena, R. Eating at Work: The Role of the Lunch-Break and Canteens for Wellbeing at Work in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 1043–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, A.J.; Sheeran, P.; Wood, W. Reflective and automatic processes in the initiation and maintenance of dietary change. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 38 (Suppl. 1), S4–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, U.N.; Aarts, H.; de Vries, N.K. Habit vs. intention in the prediction of future behaviour: The role of frequency, context stability and mental accessibility of past behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 47, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Rebar, A.L. Habits. In The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology; Sweeny, K., Robbins, M.L., Cohen, L.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Newark, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 177–182. ISBN 9781119057840. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, K.; Johnson, B.T. Habits, Quick and Easy: Perceived Complexity Moderates the Associations of Contextual Stability and Rewards With Behavioral Automaticity. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F. Sustaining Health-Protective Behaviors Such as Physical Activity and Healthy Eating. JAMA 2018, 320, 639–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevance, G.; Perski, O.; Hekler, E.B. Innovative methods for observing and changing complex health behaviors: Four propositions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekler, E.B.; Tiro, J.A.; Hunter, C.M.; Nebeker, C. Precision Health: The Role of the Social and Behavioral Sciences in Advancing the Vision. Ann. Behav. Med. 2020, 54, 805–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, E.P.; Kramer, F.M.; Cardello, A.; Schutz, H. A comparison of satiety measures. Appetite 2002, 39, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breyer, B.; Bluemke, M. Deutsche Version der Positive and Negative Affect Schedule PANAS (GESIS Panel); GESIS—Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften: Mannheim, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardi, V.; Leppanen, J.; Treasure, J. The effects of negative and positive mood induction on eating behaviour: A meta-analysis of laboratory studies in the healthy population and eating and weight disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 57, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.; Dingemans, A.; Junghans, A.F.; Boevé, A. Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 92, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wouters, S.; Jacobs, N.; Duif, M.; Lechner, L.; Thewissen, V. Negative affective stress reactivity: The dampening effect of snacking. Stress Health 2018, 34, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gower, J.C. A General Coefficient of Similarity and Some of Its Properties. Biometrics 1971, 27, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordani, P.; Ferraro, M.B.; Martella, F. An Introduction to Clustering with R; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-13-0552-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, T.; Kralle, N. Food Consumption 2020: An Welchem der Folgenden Orte Nehmen Sie Ihr Frühstück Mindestens Einmal pro Woche Ein? Graph. Statista, 2019. Available online: https://de-statista-com.ezproxy.uni-giessen.de/statistik/daten/studie/1126812/umfrage/bevorzugte-fruehstuecksorte-in-der-schweiz/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- POSpulse. Frühstück 2019: Wo Frühstückst du für Gewöhnlich? Graph. Statista, 2019. Available online: https://de-statista-com.ezproxy.uni-giessen.de/statistik/daten/studie/1093063/umfrage/umfrage-zu-haeufig-genutzten-orten-zum-fruehstuecken-in-deutschland/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Nestlé Deutschland AG. So Geteilt is(s)t Deutschland; 2019. Available online: https://www.nestle.de/medien/medieninformationen/nestl%c3%a9-studie-2019 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Bocksch, R. Frühstück—Die Wichtigste Mahlzeit am Tag? Statista, 2022. Available online: https://de-statista-com.ezproxy.uni-giessen.de/infografik/26740/anteil-der-befragten-fuer-die-fruehstueck-die-wichtigste-mahlzeit-ist/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Statista Consumer Insights. Essen und Ernährung in Deutschland 2021: Consumer Insights Datentabelle. Statista, 2022. Available online: https://de-statista-com.ezproxy.uni-giessen.de/statistik/studie/id/108720/dokument/essen-und-ernaehrung-in-deutschland/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Techniker Krankenkasse. Iss Was, Deutschland. TK-Studie zur Ernährung; 2017. Available online: https://www.tk.de/resource/blob/2033596/02bb1389edf281fbcc4ace59ea886a80/iss-was-deutschland-data.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Rauber, F.; Martins, C.A.; Azeredo, C.M.; Leffa, P.S.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Levy, R.B. Eating context and ultraprocessed food consumption among UK adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Wichmann, M. Kaum Jemand Verzichtet auf die Mittagspause. Available online: https://yougov.de/topics/travel/articles-reports/2016/09/05/kaum-jemand-verzichtet-auf-die-mittagspause (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Bouisson, J. Routinization preferences, anxiety, and depression in an elderly French sample. J. Aging Stud. 2002, 16, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.; van den Puttelaar, J.; Zandstra, E.H.; Lion, R.; de Vogel-van den Bosch, J.; Hoonhout, H.; Onwezen, M.C. Variability of Food Choice Motives: Two Dutch studies showing variation across meal moment, location and social context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 98, 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergast, F.J.; Livingstone, K.M.; Worsley, A.; McNaughton, S.A. Correlates of meal skipping in young adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.J.; Medaglia, J.D.; Jeronimus, B.F. Lack of group-to-individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6106–E6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducrot, P.; Méjean, C.; Allès, B.; Fassier, P.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. Motives for dish choices during home meal preparation: Results from a large sample of the NutriNet-Santé study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Béjar, L.M. Weekend-Weekday Differences in Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet among Spanish University Students. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racette, S.B.; Weiss, E.P.; Schechtman, K.B.; Steger-May, K.; Villareal, D.T.; Obert, K.A.; Holloszy, J.O. Influence of weekend lifestyle patterns on body weight. Obesity 2008, 16, 1826–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelmach-Mardas, M.; Kleiser, C.; Uzhova, I.; Peñalvo, J.L.; La Torre, G.; Palys, W.; Lojko, D.; Nimptsch, K.; Suwalska, A.; Linseisen, J.; et al. Seasonality of food groups and total energy intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahns, L.; Conrad, Z.; Johnson, L.K.; Scheett, A.J.; Stote, K.S.; Raatz, S.K. Diet Quality Is Lower and Energy Intake Is Higher on Weekends Compared with Weekdays in Midlife Women: A 1-Year Cohort Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1080–1086.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, S. Weekly patterns, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 134, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagni, G.; Cornwell, B. Patterns of everyday activities across social contexts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6183–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Mean/N | (SD/%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.70 | 17.25 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 135 | 58.70% |

| Female | 95 | 41.30% |

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 102 | 44.35% |

| Part-time | 36 | 15.65% |

| In education | 24 | 10.43% |

| Non-working | 67 | 29.13% |

| Missing | 1 | 0.43% |

| Household composition | ||

| Other adults in the household | ||

| No | 37 | 16.09% |

| Yes | 177 | 76.96% |

| Missing | 16 | 6.96% |

| Children in the household | ||

| No | 147 | 63.91% |

| Yes | 47 | 20.43% |

| Missing | 36 | 15.65% |

| Monthly household net-income | ||

| ≤EUR 450 | 5 | 2.17% |

| EUR 450–<1500 | 42 | 18.26% |

| EUR 1500–<2500 | 64 | 27.83% |

| EUR 2500–<4000 | 71 | 30.87% |

| ≥EUR 4000 | 44 | 19.13% |

| Missing | 4 | 1.74% |

| Situational Stability Index | Nmeals1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | etc. | ||

| Nsituations2 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.92 | … |

| 2 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.75 | … | ||

| 3 | 0.16 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.58 | … | |||

| 4 | 0.13 | 0.30 | 0.42 | … | ||||

| 5 | 0.10 | 0.25 | … | |||||

| 6 | 0.08 | … | ||||||

| etc. | … | |||||||

| Mean | Median | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 10.74 | 11 | 3.56 | 1–22 |

| Breakfast | 3.35 | 4 | 2.10 | 0–11 |

| Lunch | 3.45 | 4 | 1.88 | 0–7 |

| Dinner | 3.9 | 5 | 1.72 | 0–8 |

| N (%) | Meal Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | ||

| Total number of meals | 2461 (100%) | 770 (31.29%) | 794 (32.26%) | 897 (36.45%) | |

| Situational Dimensions | Location Home (vs. elsewhere) | 2115 (85.94%) | 686 (89.09%) | 599 (75.44%) | 830 (92.53%) |

| Hunger 1 Hungry (vs. satiated) | 1220 (49.57%) | 349 (45.32%) | 375 (47.23%) | 444 (49.50%) | |

| Social With others (vs. alone) | 1128 (45.84%) | 274 (35.58%) | 364 (45.84%) | 490 (54.63%) | |

| Activity With (vs. without activity) | 1237 (50.26%) | 403 (52.34%) | 344 (43.32%) | 490 (54.63%) | |

| Affect 1 High (vs. low negative affect) | 1142 (46.40%) | 337 (48.96%) | 364 (45.84%) | 401 (44.70%) | |

| Meal Type | Nparticipants 1 | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | 191 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.13–0.90 |

| Lunch | 200 | 0.62 | 0.20 | 0.13–0.90 |

| Dinner | 210 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.10–0.93 |

| Socio-Demographic Characteristics | Meal Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | Lunch | Dinner | |

| Test Statistic 1 N, Mean (SD) | Test Statistic 1 N, Mean (SD) | Test Statistic 1 N, Mean (SD) | |

| Age | r(189) = 0.35 *** | r(198) = 0.14 * | r(208) = 0.20 ** |

| Sex | U = 4735.5 | U = 4709.5 | U = 5544.5 |

| Male | 112, 0.66 (0.19) | 122, 0.62 (0.21) | 120, 0.68 (0.20) |

| Female | 79, 0.68 (0.18) | 78, 0.63 (0.18) | 90, 0.69 (0.19) |

| Employment status | H(3) = 20.28 *** | H(3) = 8.83 * | H(3) = 7.59 |

| Full-time | 83, 0.67 (0.19) | 91, 0.60 (0.19) | 95, 0.66 (0.19) |

| Part-time | 28, 0.64 (0.18) | 30, 0.59 (0.21) | 31, 0.74 (0.17) |

| In education | 22, 0.54 (0.17) | 22, 0.63 (0.20) | 23, 0.62 (0.24) |

| Non-working | 57, 0.74 (0.13) | 56, 0.69 (0.19) | 60, 0.72 (0.17) |

| Missing 2 | 1, 0.42 (-) | 1, 0.63 (-) | 1, 0.50 (-) |

| Household composition Other adults in the household | H(2) = 6.63 * | H(2) = 0.28 | H(2) = 0.35 |

| No | 29, 0.74 (0.16) | 33, 0.64 (0.21) | 33, 0.69 (0.22) |

| Yes | 149, 0.66 (0.19) | 152, 0.62 (0.19) | 162, 0.68 (0.19) |

| Missing | 13, 0.63 (0.12) | 15, 0.61 (0.21) | 15, 0.70 (0.19) |

| Children in the household | H(2) = 10.41 ** | H(2) = 2.65 | H(2) = 2.98 |

| No | 119, 0.70 (0.17) | 128, 0.64 (0.20) | 134, 0.70 (0.21) |

| Yes | 42, 0.61 (0.21) | 38, 0.59 (0.19) | 43, 0.66 (0.17) |

| Missing | 30, 0.62 (0.17) | 34, 0.60 (0.21) | 33, 0.68 (0.17) |

| Monthly household net-income | H(5) = 11.04 | H(5) = 3.86 | H(5) = 5.27 |

| ≤EUR 450 | 5, 0.77 (0.13) | 5, 0.71 (0.25) | 4, 0.72 (0.20) |

| EUR 450–<1500 | 37, 0.68 (0.17) | 39, 0.62 (0.18) | 40, 0.71 (0.20) |

| EUR 1500–<2500 | 48, 0.72 (0.17) | 57, 0.65 (0.20) | 56, 0.71 (0.18) |

| EUR 2500–<4000 | 61, 0.66 (0.17) | 60, 0.61 (0.21) | 67, 0.68 (0.21) |

| ≥EUR 4000 | 36, 0.59 (0.20) | 35, 0.61 (0.18) | 40, 0.64 (0.18) |

| Missing | 4, 0.65 (0.32) | 4, 0.55 (0.23) | 3, 0.70 (0.20) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wowra, P.; Joanes, T.; Gwozdz, W. In Which Situations Do We Eat? A Diary Study on Eating Situations and Situational Stability. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183967

Wowra P, Joanes T, Gwozdz W. In Which Situations Do We Eat? A Diary Study on Eating Situations and Situational Stability. Nutrients. 2023; 15(18):3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183967

Chicago/Turabian StyleWowra, Patricia, Tina Joanes, and Wencke Gwozdz. 2023. "In Which Situations Do We Eat? A Diary Study on Eating Situations and Situational Stability" Nutrients 15, no. 18: 3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183967

APA StyleWowra, P., Joanes, T., & Gwozdz, W. (2023). In Which Situations Do We Eat? A Diary Study on Eating Situations and Situational Stability. Nutrients, 15(18), 3967. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183967