Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Methods

2.2. Qualitative Methods

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkinson, M.A.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Michels, A.W. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2014, 383, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.A. Etiology of type 1 diabetes. Immunity 2010, 32, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health (UK). Diabetes (Type 1 and Type 2) in Children and Young People: Diagnosis and Management; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK): London, UK, 2015. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK315806/ (accessed on 11 December 2020).

- American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, S98–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, J.; Cunningham-Tisdall, C.; Griffin, C.; Scott, R.; Darlow, B.A.; Owens, N.; Ferguson, J.; Mackenzie, K.; Williman, J.; de Bock, M. Type 1 diabetes diagnosed before age 15 years in Canterbury, New Zealand: A 50 year record of increasing incidence. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Borriello, A.; Casaburo, F.; Del Giudice, E.M.; Iafusco, D. Body Image Problems and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Italian Adolescents With and Without Type 1 Diabetes: An Examination With a Gender-Specific Body Image Measure. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 556520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchôa, F.N.M.; Uchôa, N.M.; Daniele, T.M.d.C.; Lustosa, R.P.; Garrido, N.D.; Deana, N.F.; Aranha, Á.C.M.; Alves, N. Influence of the Mass Media and Body Dissatisfaction on the Risk in Adolescents of Developing Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, D.C.; White, E.K.; Srinivasan, V.J. A meta-analysis of the relationships between body checking, body image avoidance, body image dissatisfaction, mood, and disordered eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 745–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajadinejad, M.S.; Asgari, K.; Molavi, H.; Kalantari, M.; Adibi, P. Psychological issues in inflammatory bowel disease: An overview. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beese, S.E.; Harris, I.M.; Dretzke, J.; Moore, D. Body image dissatisfaction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019, 6, e000255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobair, P.; Stewart, S.L.; Chang, S.; D’Onofrio, C.; Banks, P.J.; Bloom, J.R. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R.V.; Hersher, B. Body Image Changes in Teen-Age Diabetics. Pediatrics 1971, 48, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, J.M.; Lloyd, G.G.; Young, R.J.; MacIntyre, C.C. Changes in eating attitudes during the first year of treatment for diabetes. J. Psychosom. Res. 1990, 34, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erkolahti, R.K.; Ilonen, T.; Saarijärvi, S. Self-image of adolescents with diabetes mellitus type-I and rheumatoid arthritis. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2003, 57, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackard, D.M.; Vik, N.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Schmitz, K.H.; Hannan, P.; Jacobs, D.R. Disordered eating and body dissatisfaction in adolescents with type 1 diabetes and a population-based comparison sample: Comparative prevalence and clinical implications. Pediatr. Diabetes 2008, 9, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, L.A.; Dewey, D. Psychological correlates of eating disorder symptoms and body image in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2013, 37, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminsky, L.A.; Dewey, D. The association between body mass index and physical activity, and body image, self esteem and social support in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2014, 38, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Prisco, F.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Zanfardino, A.; Iafusco, D. The evaluation of body image in children with type 1 diabetes: A case-control study. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcão, M.A.; Francisco, R. Diabetes, eating disorders and body image in young adults: An exploratory study about “diabulimia”. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017, 22, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, M.P.; Colton, P.A.; Daneman, D.; Rydall, A.C.; Rodin, G.M. Prediction of the Onset of Disturbed Eating Behavior in Adolescent Girls With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 1978–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.M.; Young-Hyman, D.; Fischer, S.; Markowitz, J.T.; Muir, A.B.; Laffel, L.M. Examination of Psychosocial and Physiological Risk for Bulimic Symptoms in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes Transitioning to an Insulin Pump: A Pilot Study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 43, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, A.; Cascella, C.; Chianese, A.; Galiero, I.; Zanfardino, A.; Confetto, S.; Perrone, L.; Iafusco, D. Changes in body image and onset of disordered eating behaviors in youth with type 1 diabetes over a five-year longitudinal follow-up. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 109, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, H. Women and diabetes. Diabet. Med. 1996, 13, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surgenor, L.J.; Horn, J.; Hudson, S.M. Links between psychological sense of control and disturbed eating behavior in women with diabetes mellitus. Implications for predictors of metabolic control. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiggemann, M.; McCourt, A. Body appreciation in adult women: Relationships with age and body satisfaction. Body Image 2013, 10, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sabbah, H.; Vereecken, C.A.; Elgar, F.J.; Nansel, T.; Aasvee, K.; Abdeen, Z.; Ojala, K.; Ahluwalia, N.; Maes, L. Body weight dissatisfaction and communication with parents among adolescents in 24 countries: International cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damiano, S.R.; Gregg, K.J.; Spiel, E.C.; McLean, S.A.; Wertheim, E.H.; Paxton, S.J. Relationships between body size attitudes and body image of 4-year-old boys and girls, and attitudes of their fathers and mothers. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, T.F.; Phillips, K.A.; Santos, M.T.; Hrabosky, J.I. Measuring “negative body image”: Validation of the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire in a nonclinical population. Body Image 2004, 1, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med. Care 1992, 30, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F.; Grasso, K. The norms and stability of new measures of the multidimensional body image construct. Body Image 2005, 2, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss Anselm, B.G. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, E.; Mullen, G.; Moloney, J.; Keegan, D.; Byrne, K.; Doherty, G.A.; Cullen, G.; Malone, K.; Mulcahy, H.E. Body image dissatisfaction: Clinical features, and psychosocial disability in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2015, 21, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codella, R.; Terruzzi, I.; Luzi, L. Why should people with type 1 diabetes exercise regularly? Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, L.; Harding, J.L.; Peeters, A.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. Life expectancy of type 1 diabetic patients during 1997–2010: A national Australian registry-based cohort study. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, D.; Ferriani, L.; Viana, M.C. Depression, anthropometric parameters, and body image in adults: A systematic review. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2019, 65, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J.; McClure, Z.; Tylka, T.L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Body appreciation and its psychological correlates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Body Image 2022, 42, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winters, Z.E.; Afzal, M.; Balta, V.; Freeman, J.; Llewellyn-Bennett, R.; Rayter, Z.; Cook, J.; Greenwood, R.; King, M.T. Prospective Trial Management Group Patient-reported outcomes and their predictors at 2- and 3-year follow-up after immediate latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction and adjuvant treatment. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 524–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartley, E.; Hill, B.; McPhie, S.; Skouteris, H. The associations between depressive and anxiety symptoms, body image, and weight in the first year postpartum: A rapid systematic review. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2018, 36, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.; Sim-Sim, M.M.F.; Sousa, L.; Faria-Schützer, D.B.; Surita, F.G. Self-concept and body image of people living with lupus: A systematic review. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 24, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Černelič-Bizjak, M.; Jenko-Pražnikar, Z. Body dissatisfaction predicts inflammatory status in asymptomatic healthy individuals. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, M.L.; Blackman, L.R.; Avellone, M.E. The relationship between body image discrepancy and body mass index across ethnic groups. Obes. Res. 2000, 8, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.L.; Lillis, J.; Panza, E.; Wing, R.R.; Quinn, D.M.; Puhl, R.R. Body shape concerns across racial and ethnic groups among adults in the United States: More similarities than differences. Body Image 2020, 35, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Iannotti, R.J.; Farhat, T.; Thomas, V. Ethnic differences in perceptions of body satisfaction and body appearance among U.S. Schoolchildren: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollei, I.; Lukas, C.A.; Loeber, S.; Berking, M. An app-based blended intervention to reduce body dissatisfaction: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuvia, I.; Jans, L.; Schleider, J. Secondary effects of body dissatisfaction interventions on adolescent depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diabetes | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age years (s.d.) | 37.1 (13.7) | 37.7 (13) | p = 0.84 |

| Gender (F:M) | 20:15 | 20:15 | |

| Mean BMI kg/m2 (s.d.) | 27.4 (4.5) * | 25.3 (3.8) | p = 0.05 |

| Smoking Status | p = 0.11 | ||

| Nonsmoker | 35 | 31 | |

| Current smoker | 0 | 4 | |

| Relationship status | p = 0.57 | ||

| De facto/Married | 24 | 21 | |

| Single | 9 | 13 | |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | p < 001 | ||

| NZ European | 32 | 12 | |

| Māori | 1 | 3 | |

| Pacific Peoples | 1 | 1 | |

| Asian | 1 | 17 | |

| Other Ethnicity | 0 | 2 |

| Diabetes | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BIDQ overall | 1.74 | 1.49 | 0.1 |

| BIDQ males | 1.36 | 1.28 | 0.29 |

| BIDQ females | 2.02 | 1.65 | 0.08 |

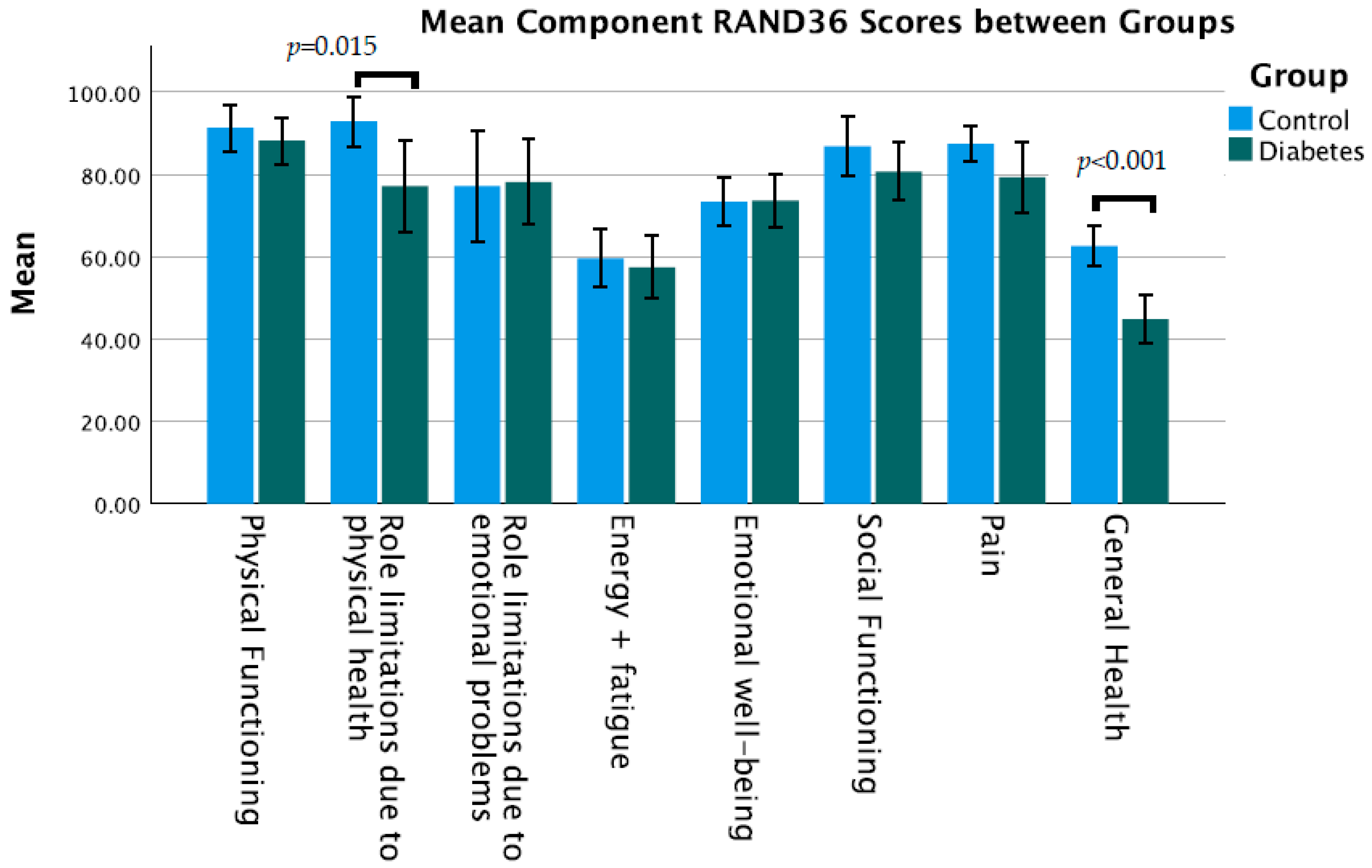

| Physical functioning | 88.1 | 91.3 | 0.43 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 77.1 | 92.9 | 0.015 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 78.1 | 77.1 | 0.91 |

| Energy + fatigue | 57.4 | 59.6 | 0.68 |

| Emotional well-being | 73.6 | 73.4 | 0.96 |

| Social functioning | 80.7 | 86.8 | 0.23 |

| Pain | 79.3 | 87.4 | 0.09 |

| General health | 44.7 | 62.6 | <0.001 |

| HADS anxiety | 4.06 | 4.54 | 0.53 |

| HADS depression | 6.45 | 3.51 | 0.002 |

| Code | Response Category | Diabetes Group No. Responses | Control Group No. Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 1a. | Concern about excess weight | 11 | 7 |

| 1b. | Concern about adipose tissue in one area | 11 | 14 |

| 1c. | Concern about low weight | 3 | 0 |

| 1d. | Effect on clothing | 15 | 15 |

| 1e. | Other physical concern | 10 | 14 |

| |||

| 2a. | Concern regarding swimming pool and beach | 9 | 15 |

| 2b. | Concern regarding exercising | 6 | 3 |

| |||

| 3a. | Fear/anxiety of public places generally | 9 | 7 |

| 3b. | Concern about being different | 3 | 1 |

| 3c. | Effect on self-esteem/confidence | 1 | 8 |

| 3d. | Effect on mood | 3 | 0 |

| 3e. | Concern regarding what others think | 1 | 1 |

| 3f. | Effect on interpersonal relationships | 0 | 1 |

| 3g. | Effect on performance/work/study | 5 | 2 |

| Diabetes Group | Control Group |

|---|---|

| Are you concerned about the appearance of some part(s) of your body, which you consider especially unattractive? What are these concerns? What specifically bothers you about the appearance of these body parts? | |

| “Recently [I] have gained weight which bothers me” (20, F, NZ European; code 1a) “I dislike how skinny my abdomen is” (18, F, Samoan; code 1c) “Weight around where I inject insulin” (31, F, NZ European; code 1a, 1b) | “[My] stomach and thighs and buttocks appear to have increased in size in the last 5 years” (57, F, NZ European; code 1b) “Scarring on the face/uneven skin tone” (23, F, Indian; code 1e) |

| What effect has your preoccupation with your appearance had on your life? | |

| “Starting to think more about food and exercise” (20, F, NZ European, code 2b) “I get quite anxious with what I wear” (18, F, Samoan, code 1d) “Sometimes feel sad/upset that I’m not small” (24, F, NZ European; code 3d) | “Change in type of clothing—not so many close fitting” (57, F, NZ European; code 1d) “Feel self-conscious” (54, F, Māori; code 3c) |

| Has your physical “defect” significantly interfered with your social life? If so, how? | |

| “Especially summer in swimsuits and less clothing” (35, F, NZ European; code 2a, 1d) “Affecting general confidence in new situations” (31, M, NZ European; code 3a) | “Not comfortable swimming” (57, F, NZ European; code 2a) “Too embarrassed to attend gatherings” (51, F, NZ European; code 3a) |

| Has your physical “defect” significantly interfered with your schoolwork, your job, or your ability to function in your role? If so, how? | |

| “Low blood sugars, need to stop what I’m doing” (57, F, NZ European; code 3g) “Felt down and unable to concentrate” (22, F, NZ European; code 3g) | “Not focusing on course work” (21, F, Other Ethnicity; code 3g) |

| Do you ever avoid things because of your physical “defect”? If so, what do you avoid? | |

| “Going to the beach/pools” (35, F, NZ European; code 2a) “Avoid exercising in public if at all” (22, F, NZ European; code 2b) “Certain clothes I would like to wear” (57, F, NZ European; code 1d) | “Swimming mainly” (57, F, NZ European; code 2a) “[I] give up on exercise sometimes” (30, F, Asian; code 2b) “Wearing dresses and shorts” (24, F, Samoan; code 1d) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inns, S.J.; Chen, A.; Myint, H.; Lilic, P.; Ovenden, C.; Su, H.Y.; Hall, R.M. Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3938. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183938

Inns SJ, Chen A, Myint H, Lilic P, Ovenden C, Su HY, Hall RM. Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(18):3938. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183938

Chicago/Turabian StyleInns, Stephen J., Amanda Chen, Helen Myint, Priyanka Lilic, Crispin Ovenden, Heidi Y. Su, and Rosemary M. Hall. 2023. "Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study" Nutrients 15, no. 18: 3938. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183938

APA StyleInns, S. J., Chen, A., Myint, H., Lilic, P., Ovenden, C., Su, H. Y., & Hall, R. M. (2023). Comparative Analysis of Body Image Dissatisfaction, Depression, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: A Case-Control Study. Nutrients, 15(18), 3938. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183938