The Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions and Changes to Takeaway Regulations in England on Consumers’ Intake and Methods of Accessing Out-of-Home Foods: A Longitudinal, Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- To determine the frequency of intake from fast food and full-service retailers.

- To determine the association of intake from fast food and full-service retailers with sociodemographic characteristics to understand the variations across the socioeconomic spectrum.

- To determine how food from fast food and full-service retailers was accessed and why.

- To explore consumers’ experiences and perspectives of using OOH food retailers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Paradigm and Study Design

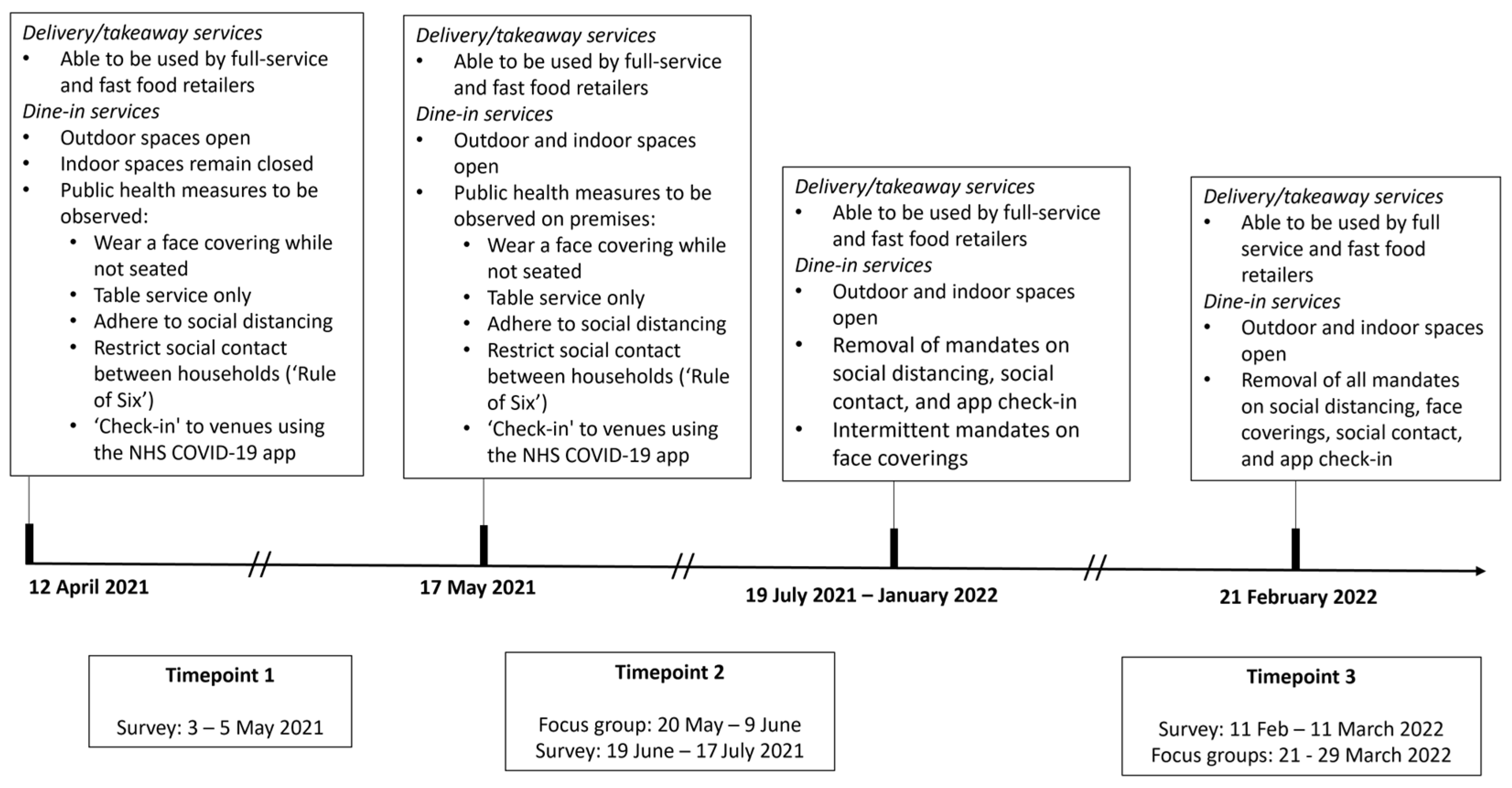

2.2. Study Context

2.3. Surveys

2.3.1. Procedure for Survey

2.3.2. Participant Recruitment and Sampling for Survey

2.3.3. Measures

2.3.4. Data Analysis for Survey

2.4. Focus Groups

2.4.1. Procedure for Focus Groups

2.4.2. Participant Recruitment and Sampling for Focus Groups

2.4.3. Data Analysis for Focus Groups

2.5. Data Integration

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.1.1. Survey

3.1.2. Focus Groups

3.2. Intake Frequency of OOH Foods

3.3. Intake of OOH Foods across Sociodemographic Groups

“I’m so busy doing everything else, it tends to be now we will just go to McDonald’s on the way home and and then just grab something quick and easy in our house usually means something that’s like full of calories and fat just because it’s, it’s just easy to grab”. (Female; 40–49 years; Focus Group at T3).

“Yeah, so tired on a Friday to think about looking nice for a meal or booking something. You’re just like no it’s just that easy… you don’t even have to get out of your car, just drive by you’ve got your meal in 10 min”. (Female; 40–49 years; Focus Group at T3).

“Yeah, I think that the what’s more noticeable for us is how much more expensive things were than before COVID. So actually, the price plays more into our decision about whether we go out or have takeaway than the COVID restrictions and and sort of like living with COVID does it’s more about the price now… I can’t justify that on a very small household budget, so we will probably get more takeaways now as a treat.”. (Female; 40–49 years; Focus Group at T3).

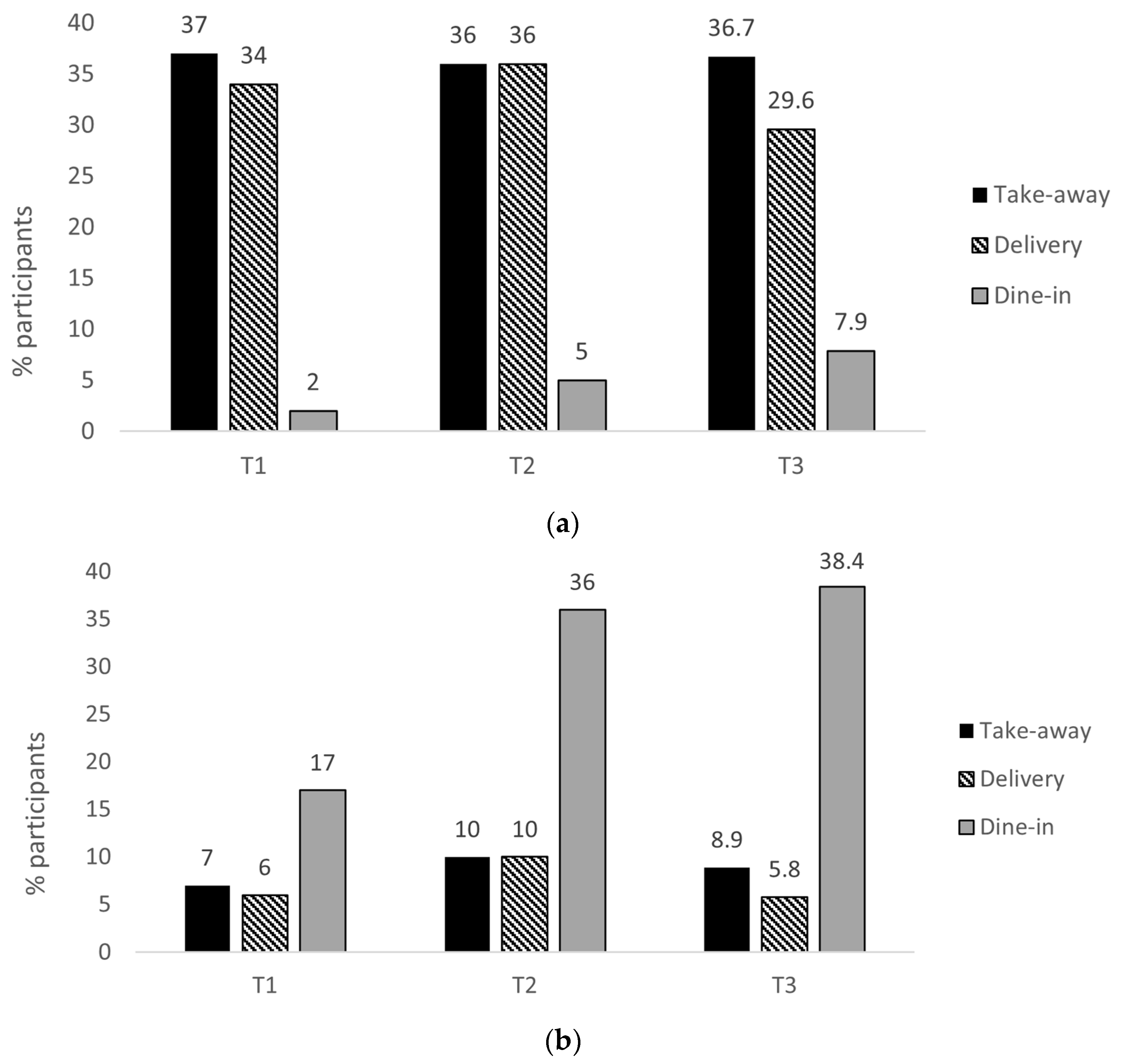

3.4. Methods of Accessing OOH Foods

“I mean it’s just a little bit like obviously, living in a house where I live with a friend, it’s just nice to get out of the house and just be together for a little bit. I would say it is just getting out of the house with us being in the house most of the time”. (Male; 20–29 years; Focus Group at T2).

“I ordered a McDonalds breakfast the other day because I had no coffee and I wanted a coffee [laughs] honestly, I thought I will get a McDonalds breakfast because you can get them delivered now with Just Eat or whoever, Deliveroo. I got two breakfasts and it came to like £12.00 and I thought, ‘What am I doing?’ I only wanted a coffee….And £12.00 so, I was thinking, how dan-gerous is it now though? Just to be able to just, I know you can always get takeaway food but there is so much more option now like McDonalds, I don’t know if that was during lockdown or whatever, but it seems like every food outlet now will have Deliveroo or Just Eat or whatever… people are going to want to go to the big boys rather than the little fellas mostly and it’s going to just take money out of their pocket but yeah, I think it’s quite dangerous the amount of availability that there is now.”. (Male; 40–49 years; Focus Group at T3).

“I used to use Deliveroo sometimes. Uhm, I used it a couple of times because I think we got a leaflet through the door where you got 50% off or something. Umm which was really good. And Uber eats as well.”. (Female; 50–59 years; Focus Group at T3).

“I think it’s about family and friendships and eating out is usually around an occasion to be fair…We like to get dressed up and just make a real night of it…it’s about, for us it’s about massively the social side of it.” (Female; 20–29 years; Focus Group at T2).

“…eating out was always about being with other people, like not just going out to get some food. It’s more about the experience of being around the people you like spending time with...” (Male; 20–29 years; Focus Group at T2).

“When you go into a retailer, you’re fulfilling a social need. When you have a takeaway, you’re having food”. (Male; 20–29 years; Focus Group at T2).

3.5. Experiences of Dining in at Full Service Retailers

“Yeah, even sitting outside, I’m just not comfortable because you don’t know people’s hygiene. You just don’t know what the cleaning regime is. You don’t know if that person sitting next to you has got COVID19 and yeah, had one vaccine, but you don’t know. You mightn’t have antibodies. You don’t know”. (Female; 50–59 years; Focus Group at T2).

“[Facilitator]…how do you feel about eating out at the moment?

[Participant] Absolutely fine…Yeah, I I don’t. I I don’t even feel like there’s any restrictions. I mean, you go into some places, there doesn’t seem to be anything sort of in place anymore, which I quite like to be honest with you.” (Female; 60–69 years; Focus Group at T3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Policy and Practice Considerations, and Future Research

- Delivery services are a growing part of the food environment and are commonly used to access fast food. This needs to be considered when developing local and national planning policies for obesity prevention.

- Research is needed to understand how delivery services influence the impact of planning policies that restrict the proliferation of fast food outlets.

- Regarding future crisis planning, if dine-in operations for full-service retailers were restricted in future, reinstating takeaway/delivery services could be considered. They would help preserve business and allow those considered vulnerable to enjoy these retailers.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UK Government. Prime Minister’s Statement on Coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Institute for Government. Timeline of UK Government Coronavirus Lockdowns and Restrictions. 2022. Available online: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/charts/uk-government-coronavirus-lockdowns (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- UK Government. COVID-19 Response: Living with COVID-19. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-response-living-with-covid-19 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- UK Government. The Town and Country Planning (Use Classes) (Amendment) (England) Regulations 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2020/757/made (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- UK Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Government to Grant Permission for Pubs and Retailers to Operate as Takeaways as Part of Coronavirus Response [Press Release]. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-to-grant-permission-for-pubs-and-restaurants-to-operate-as-takeaways-as-part-of-coronavirus-response#:~:text=out%20this%20change-,Planning%20rules%20will%20be%20relaxed%20so%20pubs%20and%20restaurants%20can,to%20a%20hot%20food%20takeaway (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Moore, H.J.; Lake, A.A.; O’Malley, C.L.; Bradford, C.; Gray, N.; Chang, M.; Mathews, C.; Townshend, T.G. The impact of COVID-19 on the hot food takeaway planning regulatory environment: Perspectives of local authority professionals in the North East of England. Perspect. Public Health 2022, 175791392211063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.B.; Das, S.K.; Suen, V.M.M.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Kuriyan, R.; Steiner-Asiedu, M.; Taetzsch, A.; Anderson, A.K.; Silver, R.E.; Barger, K.; et al. Measured energy content of frequently purchased retailer meals: Multi-country cross sectional study. BMJ 2018, 363, k4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworowska, A.; MBlackham, T.; Long, R.; Taylor, C.; Ashton, M.; Stevenson, L.; Glynn Davies, I. Nutritional composition of takeaway food in the UK. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 44, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischhacker, S.E.; Evenson, K.R.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Ammerman, A.S. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e460–e471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgoine, T.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Associations between exposure to takeaway food outlets, takeaway food consumption, and body weight in Cambridgeshire, UK: Population based, cross sectional study. BMJ 2014, 348, g1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. Tackling Obesity: The Role of the NSH in a Whole-System Approach; The King’s Fund: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/tackling-obesity-nhs (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Public Health England. Obesity and the Environment: Density of Fast Food Outlets at 31/12/2017. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/fast-food-outlets-density-by-local-authority-in-england (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Dicken, S.J.; Mitchell, J.J.; Le Vay, J.N.; Beard, E.; Kale, D.; Herbec, A.; Shahab, L. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Weight and BMI among UK Adults: A Longitudinal Analysis of Data from the HEBECO Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundijo, D.A.; Tas, A.A.; Onarinde, B.A. Exploring the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Eating and Purchasing Behaviours of People Living in England. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, C.; Costanzo, S.; Ghulam, A.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Bonaccio, M. Impact of Nationwide Lockdowns Resulting from the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Intake, Eating Behaviors, and Diet Quality: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2022, 13, 388–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Jeyakumar, D.T.; Jayawardena, R.; Chourdakis, M. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on snacking habits, fast-food and alcohol consumption: A systematic review of the evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 3038–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acton, R.B.; Vanderlee, L.; Cameron, A.J.; Goodman, S.; Jáuregui, A.; Sacks, G.; White, C.M.; White, M.; Hammond, D. Self-Reported Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Diet-Related Behaviors and Food Security in 5 Countries: Results from the International Food Policy Study 2020. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 35S–46S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albalawi, A.; Hambly, C.; Speakman, J.R. The usage of different types of food outlets was not significantly associated with body mass index during the third COVID-19 national lockdown in the United Kingdom. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2022, 8, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V.; Vi, L.H.; Beer, S.; Ermolaev, V.A. The COVID-19 pandemic and food consumption at home and away: An exploratory Study of English households. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, D.L. Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: A Pragmatic Approach; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/integrating-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods-a-pragmatic-approach (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Creswell, J.; Clarke, V.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publishing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prolific Research. 2022. Available online: https://www.prolific.co/ (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- UK Government. Income and Tax by County and Region. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/income-and-tax-by-county-and-region-2010-to-2011 (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Bujang, M.A.; Sa’at, N.; Sidik, T.M.I.T.A.B.; Joo, L.C. Sample Size Guidelines for Logistic Regression from Observational Studies with Large Population: Emphasis on the Accuracy Between Statistics and Parameters Based on Real Life Clinical Data. Malays. J. Med Sci. 2018, 25, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Agriculture (USDA). U.S Household Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design with Screeners. In Economic Research Service; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cleghorn, C.L.; Harrison, R.A.; Ransley, J.K.; Wilkinson, S.; Thomas, J.; Cade, J.E. Can a dietary quality score derived from a short-form FFQ assess dietary quality in UK adult population surveys? Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bush, K.; Kivlahan, D.R.; McDonell, M.B.; Fihn, S.D.; Bradley, K.A. The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C). An Effective Brief Screening Test for Problem Drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998, 158, 1789–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.L.F.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Given, L. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Available online: https://methods.sagepub.com/reference/sage-encyc-qualitative-research-methods (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.M.; Ormston, R. (Eds.) Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grossoehme, D.; Lipstein, E. Analyzing longitudinal qualitative data: The application of trajectory and recurrent cross-sectional approaches. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistica. Median Annual Earnings for Full-Time Employees in the United Kingdom in 2021, by Region (in GBP). 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/416139/full-time-annual-salary-in-the-uk-by-region/ (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- KPMG. Food for Thought: What the Takeaway and Delivery Boom Means for Retailer Operators. 2021. Available online: https://kpmg.com/uk/en/home/insights/2021/07/how-restaurant-operators-can-take-advantage-of-the-takeaway-boom.html#:~:text=Strategic%20crossroads,stand%20out%20from%20the%20crowd. (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Keeble, M.; Adams, J.; Burgoine, T. Investigating experiences of frequent online food delivery service use: A qualitative study in UK adults. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.; Goffe, L.; Brown, T.; A Lake, A.; Summerbell, C.; White, M.; Wrieden, W.; Adamson, A.J. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008–12). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Agency. Exploring Food Attitudes and Behaviours in the UK: Findings from the Food and You Survey 2010. 2010. Available online: https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-and-you-2010-main-report.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- Lumina Intelligence. UK Foodservice Delivery Market Report 2021. Available online: https://store.lumina-intelligence.com/product/uk-foodservice-delivery-market-report-2021/ (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Ambrose, J. Deliveroo Orders Double as Appetite for Takeaways Grows; The Guardian: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Keeble, M.; Burgoine, T.; White, M.; Summerbell, C.; Cummins, S.; Adams, J. How does local government use the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets? A census of current practice in England using document review. Heal. Place 2019, 57, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Nago, E.; Verstraeten, R.; Roberfroid, D.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stok, F.M.; de Vet, E.; de Wit, J.B.; Luszczynska, A.; Safron, M.; de Ridder, D.T. The proof is in the eating: Subjective peer norms are associated with adolescents’ eating behaviour. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nago, E.S.; Lachat, C.K.; Dossa, R.A.M.; Kolsteren, P.W. Association of Out-of-Home Eating with Anthropometric Changes: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, I.N.; Curioni, C.; Sichieri, R. Association between eating out of home and body weight. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Jones, A.; Whitelock, V.; Mead, B.R.; Haynes, A. (Over)eating out at major UK retailer chains: Observational study of energy content of main meals. BMJ 2018, 363, k4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miura, K.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G. Socioeconomic differences in takeaway food consumption and their contribution to inequalities in dietary intakes. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 820–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astbury, C.C.; Foley, L.; Penney, T.L.; Adams, J. How Does Time Use Differ between Individuals Who Do More versus Less Foodwork? A Compositional Data Analysis of Time Use in the United Kingdom Time Use Survey 2014–2015. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. Inflation and Price Indices [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Eskandari, F.; Lake, A.A.; Rose, K.; Butler, M.; O’Malley, C. A mixed-method systematic review and meta-analysis of the influences of food environments and food insecurity on obesity in high-income countries. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3689–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, G.S.; Christiansen, P.; Hardman, C.A. Household Food Insecurity, Diet Quality, and Obesity: An Explanatory Model. Obesity 2020, 29, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Government. Available online: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/explainers/cost-living-crisis (accessed on 2 October 2022).

| Title 1 | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | X | ||

| Fruit and vegetable intake in the preceding 7 days (SFFFQ) | X | ||

| Pre-pandemic frequency of eating from different retailers | X | ||

| Usual alcohol intake (AUDIT-C) | X | ||

| Alcohol intake in the preceding 7 days (modified AUDIT-C) | X | X | X |

| Physical activity in the preceding 7 days (IPAQ short) | X | X | X |

| Frequency of eating from fast food and full-service retailers in the preceding 7 days | X | X | X |

| Use of dine-in, delivery, or takeaway services in the preceding 7 days | X | X | X |

| T1 n = 701 | T2 n = 615 | T3 n = 490 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (%) | 49.9 | 49.8 | 47.4 |

| Age (years (SD)) | 36.0 (14.2) | 36.5 (14.3) | 38.7 (14.6) |

| Age groups | |||

| 18–24 years (%) | 29.2 | 27.4 | 21.8 |

| 25–49 years (%) | 50.8 | 52.0 | 52.5 |

| 50 years and over (%) | 20.0 | 20.6 | 25.7 |

| Region | |||

| North East, England | 70.3 | 70.0 | 73.1 |

| North West, England | 29.7 | 30.0 | 26.9 |

| White ethnic background (%) | 90.6 | 90.5 | 92.7 |

| Employment status | |||

| Full-time employed (%) | 45.5 | 44.9 | 45.3 |

| Part-time employed (%) | 19.1 | 20.2 | 21.0 |

| Unemployed (%) | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.0 |

| Full-time student (%) | 16.0 | 15.8 | 11.8 |

| Part-time Student (%) | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.4 |

| Carer and other (%) | 6.4 | 5.9 | 9.5 |

| A-level or lower (%) | 35.8 | 35.2 | 35.3 |

| Issues with access to food | |||

| Definition 1 (%) a | 14.7 | 14.3 | 13.3 |

| Definition 2 (%) b | 8.6 | 8.3 | 7.9 |

| Annual household income | |||

| Less than GBP 16,000 (%) | 21.4 | 20.4 | 21.0 |

| GBP 16,000–29,999 (%) | 29.7 | 30.3 | 30.2 |

| GBP 30,000–49,999 (%) | 26.5 | 26.8 | 23.3 |

| GBP 50,000 and over (%) | 22.4 | 22.5 | 25.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2 (SD)) c | 26.9 (sd = 6.6) | 26.9 (sd = 6.6) | 27.1 (sd = 6.6) |

| Obesity (%) | 26.8 | 26.8 | 29.0 |

| Meeting five-a-day fruit and vegetable serving guideline (%) | 30.2 | 32.0 | 31.7 |

| MET hours per week of physical activity d | 48.3 (sd = 45.5) | 46.5 (sd = 41.3) | 48.3 (sd = 45.5) |

| Able to have food delivered by delivery service e.g., Just Eat (%) | 96.0 | 96.0 | 95.6 |

| T2 n = 22 | T3 n = 12 | |

|---|---|---|

| Women (n; %) | 12; 55 | 6; 50 |

| Age group (n; %) | ||

| <30 years | 9; 41 | 3; 25 |

| 30–39 years | 2; 9 | 0; 0 |

| 40–49 years | 3; 14 | 3; 25 |

| 50–59 years | 4; 18 | 4; 33 |

| ≥60 years | 4; 18 | 2; 17 |

| Annual household income (n; %) | ||

| <GBP 10,000 | 2; 9 | 0; 0 |

| GBP 10,000–19,999 | 4; 18 | 2; 17 |

| GBP 20,000–29,999 | 4; 18 | 1; 8 |

| GBP 30,000–39,999 | 3; 14 | 1; 8 |

| GBP 40,000–49,999 | 2; 9 | 3; 25 |

| GBP 50,000–99,999 | 5; 23 | 5; 42 |

| ≥GBP 100,000 | 2; 9 | 0; 0 |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 years old | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25–49 years old | 0.486 *** | 0.478 *** | 0.522 ** |

| (0.111) | (0.121) | (0.158) | |

| 50 and older | 0.177 *** | 0.164 *** | 0.225 *** |

| (0.0510) | (0.0509) | (0.0791) | |

| North East | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| North West | 0.767 | 1.211 | 1.386 |

| (0.154) | (0.259) | (0.334) | |

| Degree or higher | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| A-level or lower | 1.040 | 1.390 * | 0.946 |

| (0.172) | (0.246) | (0.184) | |

| Healthy BMI | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight BMI | 1.193 | 1.186 | 1.176 |

| (0.229) | (0.239) | (0.271) | |

| Obese BMI | 1.607 ** | 2.212 *** | 1.846 *** |

| (0.310) | (0.460) | (0.420) | |

| Household income < GBP 16K | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GBP 16–29K | 1.044 | 1.431 | 1.188 |

| (0.255) | (0.376) | (0.345) | |

| GBP 30–49K | 1.383 | 1.521 | 1.317 |

| (0.352) | (0.418) | (0.396) | |

| GBP 50K or greater | 1.651* | 1.558 | 1.097 |

| (0.444) | (0.453) | (0.353) | |

| No food access issues | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Food access | 1.652 ** | 2.597 *** | 2.107 ** |

| (0.400) | (0.661) | (0.619) | |

| Not in employment/Other | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Full-time employed | 1.516 * | 1.385 | 1.605 |

| (0.369) | (0.353) | (0.466) | |

| Part-time employed | 1.242 | 0.990 | 1.224 |

| (0.312) | (0.257) | (0.352) | |

| Student | 1.199 | 0.881 | 1.243 |

| (0.324) | (0.251) | (0.471) | |

| Carer | 3.510 *** | 1.094 | 1.936 |

| (1.318) | (0.422) | (0.856) | |

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 0.967 | 1.153 | 0.896 |

| (0.163) | (0.208) | (0.180) | |

| /cut1 | 0.469 | 0.683 | 0.784 |

| (0.259) | (0.441) | (0.543) | |

| /cut2 | 3.076 ** | 4.123 ** | 4.004 ** |

| (1.701) | (2.670) | (2.789) | |

| /cut3 | 12.02 *** | 13.93 *** | 12.60 *** |

| (6.812) | (9.132) | (8.921) | |

| Observations | 599 | 550 | 427 |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 years old | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 25–49 years old | 0.574 ** | 0.449 *** | 0.553 * |

| (0.149) | (0.119) | (0.175) | |

| 50 and older | 0.336 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.399 *** |

| (0.116) | (0.118) | (0.141) | |

| North East | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| North West | 0.683 | 1.289 | 0.914 |

| (0.167) | (0.293) | (0.233) | |

| Degree or higher | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| A-level or lower | 0.636 ** | 0.951 | 0.818 |

| (0.133) | (0.175) | (0.167) | |

| Healthy BMI | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Overweight BMI | 1.070 | 0.913 | 1.140 |

| (0.243) | (0.190) | (0.268) | |

| Obese BMI | 0.840 | 0.905 | 1.271 |

| (0.203) | (0.195) | (0.298) | |

| Household income < GBP 16K | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| GBP 16–29K | 1.334 | 1.637 * | 1.036 |

| (0.402) | (0.445) | (0.313) | |

| GBP 30–49K | 1.305 | 1.796 ** | 1.288 |

| (0.406) | (0.524) | (0.402) | |

| GBP 50K or greater | 1.320 | 2.406 *** | 1.925 * |

| (0.427) | (0.731) | (0.646) | |

| No food access issues | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Food access | 1.077 | 1.609 * | 1.245 |

| (0.318) | (0.433) | (0.384) | |

| Not in employment/Other | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Full-time employed | 1.175 | 1.329 | 1.340 |

| (0.344) | (0.348) | (0.392) | |

| Part-time employed | 1.024 | 1.546 | 1.035 |

| (0.312) | (0.416) | (0.307) | |

| Student | 1.095 | 1.499 | 1.498 |

| (0.346) | (0.454) | (0.571) | |

| Carer | 0.207 ** | 0.849 | 1.035 |

| (0.158) | (0.361) | (0.436) | |

| Male | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.241 | 1.300 | 1.130 |

| (0.247) | (0.248) | (0.234) | |

| /cut1 | 1.610 | 2.303 | 1.059 |

| (1.032) | (1.480) | (0.759) | |

| /cut2 | 7.042 *** | 16.41 *** | 5.653 ** |

| (4.583) | (10.75) | (4.082) | |

| /cut3 | 22.68 *** | 53.15 *** | 21.48 *** |

| (15.49) | (35.92) | (16.04) | |

| Observations | 599 | 524 | 427 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fong, M.; Scott, S.; Albani, V.; Brown, H. The Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions and Changes to Takeaway Regulations in England on Consumers’ Intake and Methods of Accessing Out-of-Home Foods: A Longitudinal, Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163636

Fong M, Scott S, Albani V, Brown H. The Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions and Changes to Takeaway Regulations in England on Consumers’ Intake and Methods of Accessing Out-of-Home Foods: A Longitudinal, Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(16):3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163636

Chicago/Turabian StyleFong, Mackenzie, Steph Scott, Viviana Albani, and Heather Brown. 2023. "The Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions and Changes to Takeaway Regulations in England on Consumers’ Intake and Methods of Accessing Out-of-Home Foods: A Longitudinal, Mixed-Methods Study" Nutrients 15, no. 16: 3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163636

APA StyleFong, M., Scott, S., Albani, V., & Brown, H. (2023). The Impact of COVID-19 Restrictions and Changes to Takeaway Regulations in England on Consumers’ Intake and Methods of Accessing Out-of-Home Foods: A Longitudinal, Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients, 15(16), 3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163636