Using Community-Based Participatory Research Methods to Inform the Development of Medically Tailored Food Kits for Hispanic/Latine Adults with Hypertension: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Questionnaires

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

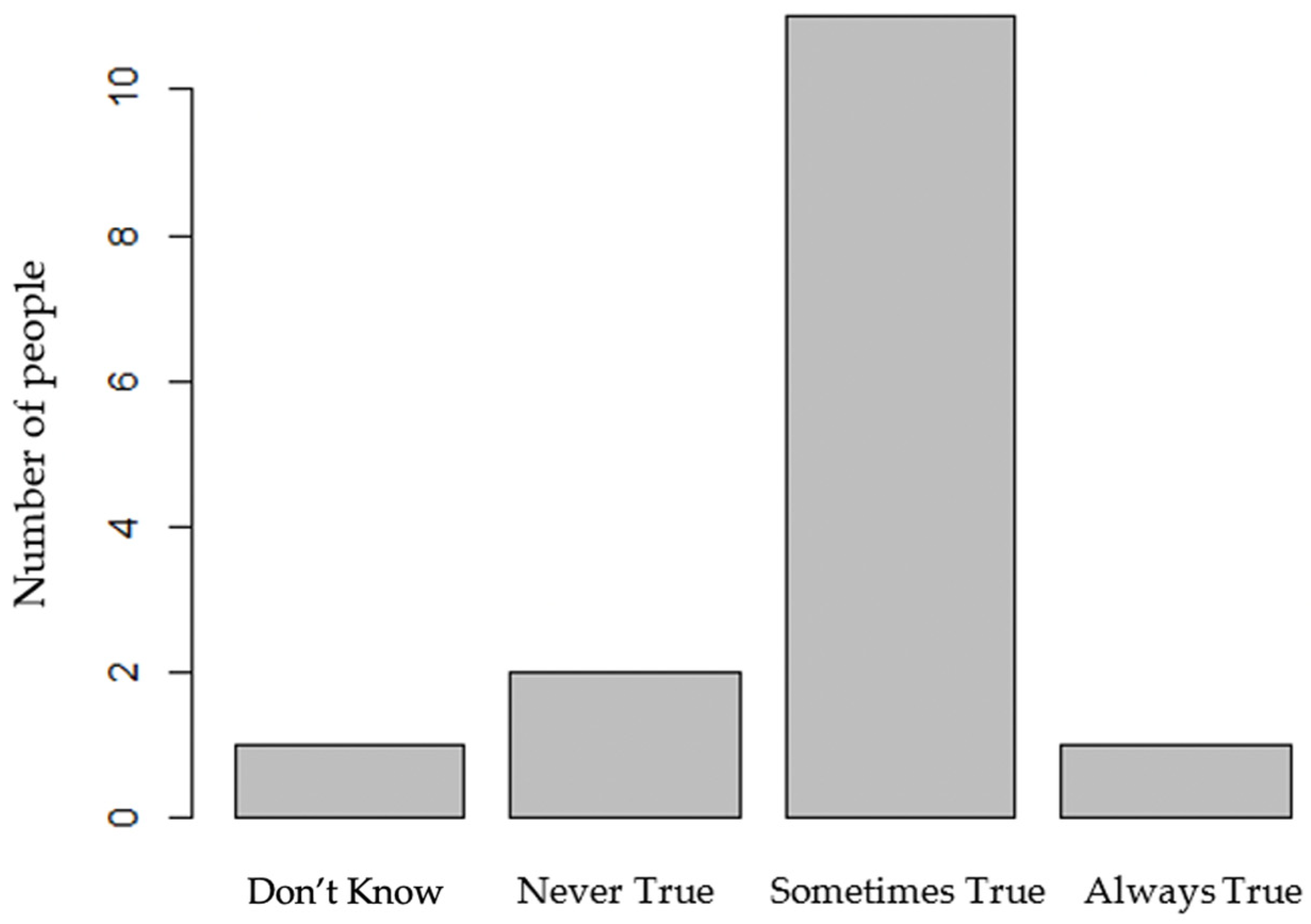

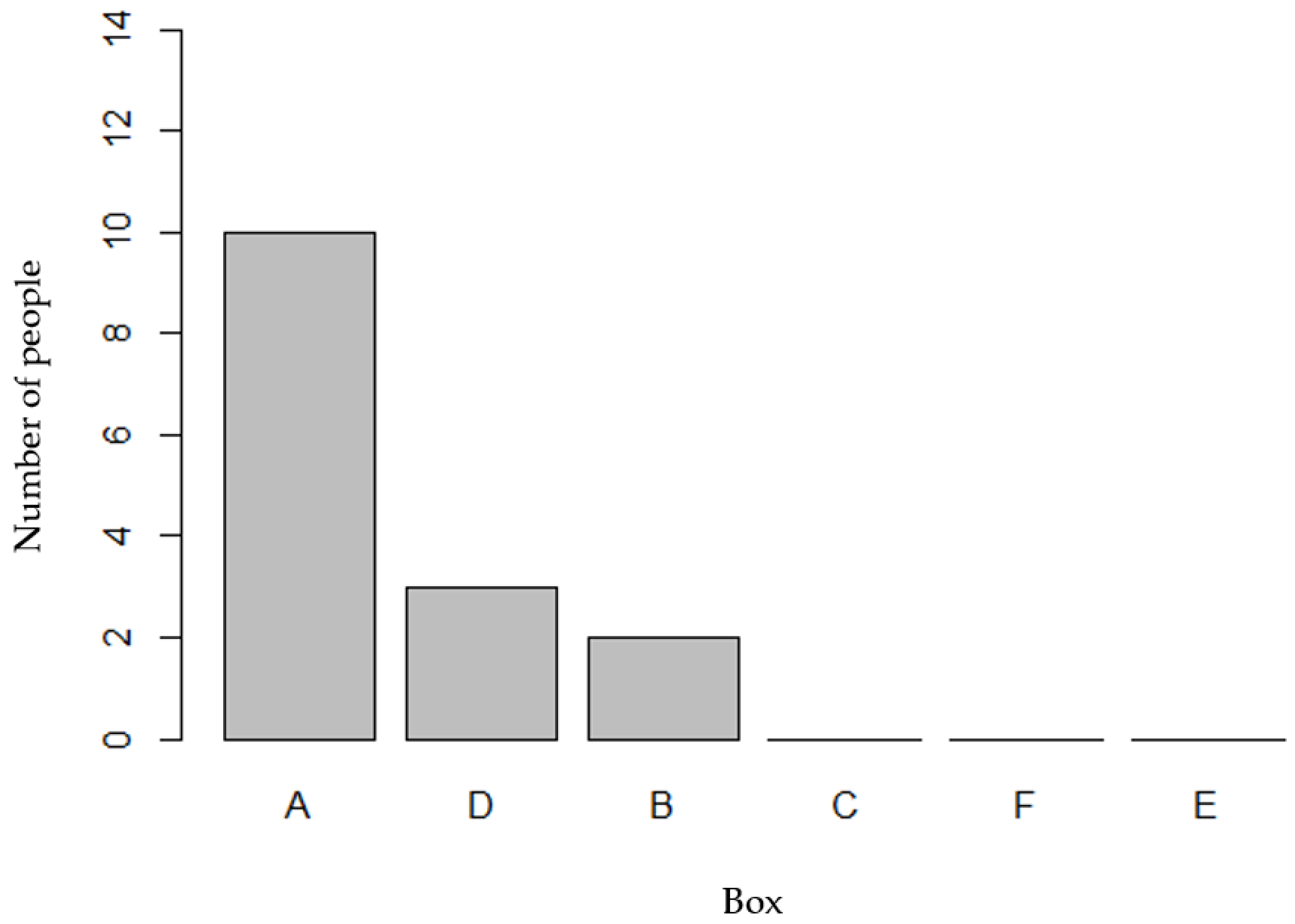

3.2. Box Preference and Cultural Appropriateness

3.3. Themes Identified

3.3.1. Theme 1: Preference for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables

“The best option is the most natural, because of the chemicals that the canned goods have. But in reality, all the boxes had something good, because tomatoes, apples, bananas, carrots, kale, spinach, broccoli, all of those are good things.”

“I know that a lot of people in the United States use a lot of canned foods. They use it because it’s more convenient and fast, and we don’t, we usually grow it and like it more natural [in Mexico].”

3.3.2. Theme 2: Time, Money, and Transportation Are Barriers to Obtaining Fruits and Vegetables

“Because of the economy I don’t buy much for vegetables. There are times when I don’t but I should because I like the vegetables more than the meat. I really like to combine meat with vegetables, but at times I don’t have enough money to buy everything I would want to.”

3.3.3. Theme 3: Staple Items Are Used to Compliment Fruit and Vegetable Intake

“...I feel like the onion, for me it’s important, the onion. It gives more flavor to the foods. I don’t know. We come from Latin America to here, and we lost a few items. Those flavors are different, and our diet changed, you know, until we adapt here to a different diet.”

3.3.4. Theme 4: Variable Degrees of Health Literacy Are Present

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kershaw, K.N.; Giacinto, R.E.; Gonzalez, F.; Isasi, C.R.; Salgado, H.; Stamler, J.; Talavera, G.A.; Tarraf, W.; Van Horn, L.; Wu, D.; et al. Relationships of nativity and length of residence in the U.S. with favorable cardiovascular health among Hispanics/Latinos: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, N.; Murray-Kolb, L.E.; Mitchell, D.C.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Na, M. Food Insecurity and Mental Well-Being in Immigrants: A Global Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 63, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibe, L.W.; Bazargan, M. Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Older African American and Hispanic Adults with Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2022, 8, 23337214211057730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Know Your Risk for Heart Disease. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/risk_factors.htm (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Overweight & Obesity Statistics. Available online: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity#:~:text=More%20than%201%20in%203,who%20are%20overweight%20(27.5%25) (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- Micha, R.; Peñalvo, J.L.; Cudhea, F.; Imamura, F.; Rehm, C.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017, 317, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahat, S.; Moffat, T.; Newbold, K.B. Understanding the Healthy Immigrant Effect in the Context of Mental Health Challenges: A Systematic Critical Review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 1564–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, A.H.; Appel, L.J.; Vadiveloo, M.; Hu, F.B.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Rebholz, C.M.; Sacks, F.M.; Thorndike, A.N.; Van Horn, L.; Wylie-Rosett, J. 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 144, e472–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, B.T.; Wu, D.; Hou, L.; Dai, Q.; Castaneda, S.F.; Callo, L.C.; Talavera, G.A.; Sotres-Alvarez, D.; Van Horn, L.; Beasley, J.M.; et al. DASH diet and prevalent metabolic syndrome in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Prev. Med. Rep. 2019, 15, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. DASH Eating Plan. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/dash-eating-plan (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Chiavaroli, L.; Viguiliouk, E.; Nishi, S.K.; Mejia, S.B.; Rahelić, D.; Kahleová, H.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Kendal, C.W.C.; Sievenpiper, J.L. DASH dietary pattern and cardiometabolic outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, D.W.K.; Sutanto, C.N.; Loh, W.W.; Lee, W.W.; Yao, Y.; Ong, C.N.; Kim, J.E. Skin carotenoids status as a potential surrogate marker for cardiovascular disease risk determination in middle-aged and older adults. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, R.; Yi, S.S.; Nonas, C. Increasing access to fruits and vegetables: Perspectives from the New York City experience. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e29–e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Love, P.; Mathers, J.C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Olstad, D.L. Cultural adaptations and tailoring of public health nutrition interventions in Indigenous peoples and ethnic minority groups: Opportunities for personalised and precision nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2023, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rising, K.L.; Kemp, M.; Davidson, P.; Hollander, J.E.; Jabbour, S.; Jutkowitz, E.; Leiby, B.E.; Marco, C.; McElwee, I.; Mills, G.; et al. Assessing the impact of medically tailored meals and medical nutrition therapy on type 2 diabetes: Protocol for Project MiNT. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2021, 108, 106511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Delahanty, L.M.; Terranova, J.; Steiner, B.; Ruazol, M.P.; Singh, R.; Shahid, N.N.; Wexler, D.J. Medically Tailored Meal Delivery for Diabetes Patients with Food Insecurity: A Randomized Cross-over Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belak, L.; Owens, C.; Smith, M.; Calloway, E.; Samnadda, L.; Egwuogu, H.; Schmidt, S. The impact of medically tailored meals and nutrition therapy on biometric and dietary outcomes among food-insecure patients with congestive heart failure: A matched cohort study. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Randall, L.; Cranston, K.; Waters, D.B.; Hsu, J. Association Between Receipt of a Medically Tailored Meal Program and Health Care Use. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, C.M.; Strader, L.C.; Pratt, J.G.; Maiese, D.; Hendershot, T.; Kwok, R.K.; Hammond, J.A.; Huggins, W.; Jackman, D.; Pan, H.; et al. The PhenX Toolkit: Get the most from your measures. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROMIS Scale v1.2-Global Health. 2023. Available online: https://www.healthmeasures.net/index.php?option=com_instruments&view=measure&id=778&Itemid=992 (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form [Survey]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute. Dietary Screener Questionnaire (DSQ) in the NHANES 2009-10: Dietary Factors, Food Items Asked, and Testing Status for DSQ. Division of Cancer Control and Population Science. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/evaluation.html#pub (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Schnefke, C.H.; Tumilowicz, A.; Pelto, G.H.; Gebreyesus, S.H.; Gonzalez, W.; Hrabar, M.; Mahmood, S.; Pedro, C.; Picolo, M.; Possolo, E.; et al. Designing an ethnographic interview for evaluation of micronutrient powder trial: Challenges and opportunities for implementation science. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Definitions of Food Security. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/definitions-of-food-security/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Data Processing & Scoring Procedures Using Current Methods (Recommended). Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/nhanes/dietscreen/scoring/current/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Byker Shanks, C.; Parks, C.A.; Izumi, B.; Andress, L.; Yaroch, A.L. The Need to Incorporate Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: Reflections from a National Initiative Measuring Fruit and Vegetable Intake. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 1241–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citations. Available online: https://projectredcap.org/resources/citations/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Sweeney, L.H.; Carman, K.; Varela, E.G.; House, L.A.; Shelnutt, K.P. Cooking, Shopping, and Eating Behaviors of African American and Hispanic Families: Implications for a Culturally Appropriate Meal Kit Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Security in the U.S. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/#foodsecure (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Tucker, K.L. Dietary Patterns in Latinx Groups. J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 2505–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overcash, F.; Reicks, M. Diet Quality and Eating Practices among Hispanic/Latino Men and Women: NHANES 2011-2016. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, L.A.; Amezquita, A.; Hooker, S.P.; Garcia, D.O. Mexican-origin male perspectives of diet-related behaviors associated with weight management. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 1824–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsivais, P.; Rehm, C.D.; Drewnowski, A. The DASH diet and diet costs among ethnic and racial groups in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1846, Erratum in JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1922–1924. [Google Scholar]

- Summary Findings: Food Price Outlook 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-price-outlook/summary-findings/ (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- What Is Health Literacy? Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Wilson, M.D.; Ramírez, A.S.; Arsenault, J.E.; Miller, L.M.S. Nutrition Label Use and Its Association with Dietary Quality Among Latinos: The Roles of Poverty and Acculturation. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldheer, S.; Scartozzi, C.; Knehans, A.; Oser, T.; Sood, N.; George, D.R.; Smith, A.; Cohen, A.; Winkels, R.M. A Systematic Scoping Review of How Healthcare Organizations Are Facilitating Access to Fruits and Vegetables in Their Patient Populations. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2859–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Box Label (Total Servings) | Fruits, Modality Provided (Servings) | Vegetables, Modality Provided (Servings) |

|---|---|---|

| Box A (47) | 1 mango, fresh (2) 1 avocado, fresh (2) 3 bananas, fresh (3) 1 pound of grapes, fresh (8) 3 large apples, fresh (6) | 3 tomatoes, fresh (3) 2 cucumbers, fresh (4) 2 chayote squash, fresh (2) Broccoli, fresh (4) Spinach, fresh (3) 1 head of lettuce, fresh (2) 8-10 carrots, fresh (8) |

| Box B (56) | Mangoes, frozen (6) Strawberries, frozen (4) 1 avocado, fresh (2) 3 bananas, fresh (3) 1 small watermelon, fresh (10) | 3 tomatoes, fresh (3) 2 cucumbers, fresh (4) 8-10 carrots, fresh (8) Broccoli, frozen (8) Asparagus, frozen (8) |

| Box C (52) | Mangoes, frozen (6) 1 avocado, fresh (2) 3 bananas, fresh (3) 1 pound of grapes, fresh (8) 6 single servings of applesauce, canned (6) | Diced tomatoes, canned (3) 2 cucumbers, fresh (4) 8-10 carrots, fresh (8) Broccoli, frozen (8) Corn, canned (4) |

| Box D (50) | 1 mango, fresh (2) 1 avocado, fresh (2) 3 oranges, fresh (3) 1 cantaloupe, fresh (8) 5 peaches, fresh (5) | 3 tomatoes, fresh (3) 2 bell peppers (red/green), fresh (4) 1 butternut squash, fresh (8) Broccoli, fresh (4) Spinach, fresh (3) Kale, fresh (2) 6-8 carrots, fresh (6) |

| Box E (49) | Mangoes, frozen (6) Peaches, frozen (4) 1 avocado, fresh (2) 3 oranges, fresh (3) Strawberries, frozen (4) | 3 tomatoes, fresh (3) 2 bell peppers (red/green), fresh (4) 4 sweet potatoes (4) Broccoli, frozen (8) Spinach, frozen (3) Kale, fresh (2) 6-8 carrots, fresh (6) |

| Box F (49) | Mangoes, frozen (6) Papaya, fresh (4) 1 avocado, fresh (2) 3 oranges, fresh (3) Pineapple, canned (2) Mixed fruit (peaches, mango, pineapple, and strawberries), frozen (2) | Diced tomatoes, canned (3) 2 bell peppers (red/green), fresh (4) 2 sweet potatoes, fresh (4) Broccoli, frozen (8) Spinach, frozen (3) Kale, fresh (2) 2 pumpkins, canned (6) |

| Variable (n = 15) | n per Category (Percent Sample) | Mean Servings of Total F/V per Day (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 12 (80) | 2.7 (1.4) |

| Male | 3 (20) | 2.2 (1.4) |

| Education | ||

| Some High School | 6 (40.1) | 3.3 (1.6) |

| High School Graduate | 2 (13.3) | 1.6 (0.3) |

| Some College, No Degree | 2 (13.3) | 1.3 (0.4) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 2 (13.3) | 2.7 (1.4) |

| Professional Degree | 1 (6.7) | 1.8 (0.0) |

| Not Reported | 2 (13.3) | 3.3 (0.6) |

| Employment | ||

| Housekeeping | 2 (13.3) | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Looking for Work | 4 (26.7) | 2.1 (1.3) |

| Working Now | 6 (40) | 2.6 (1.4) |

| Retired | 1 (6.7) | 3.8 (0.0) |

| Temporarily Laid Off | 1 (6.7) | 5.2 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (6.7) | 1.8 (0.0) |

| Chronic Disease Diagnosis * | ||

| Hypertension | 10 (66.7) | 2.3 (1.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 5 (33.3) | 2.5 (1.2) |

| Pre-Diabetes | 3 (20.0) | 2.0 (0.9) |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus | 6 (40.0) | 3.7 (1.2) |

| >1 Chronic Disease | 7(46.7) | 2.7 (1.2) |

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh foods and vegetables are top food preference, followed by frozen fruits and vegetables. | Frozen food is recognized as “natural” and can be preserved longer than fresh F/V. Canned foods are reserved as a last resort and can be perceived to have chemicals and/or be high in sodium and sugar. Certain cultural canned foods like corn and beans are accepted. | Participant (P)7: “...the best option is the most natural because of the chemicals that the canned goods have.” |

| P5: “Personally, when I just arrived to the United States, we didn’t consume much of the canned products. Each time someone would go to the store close to home, there would be fruits, elote, or fresh tomatoes; it was natural not canned. It was hard for me to cook with the canned food because it has another type of flavor.” | ||

| Individuals have a like or dislike for fresh fruits and vegetables based on personal food preferences and/or cultural upbringing. | P14: “...For example, I would like to exchange [the kale] because why bring it if I’m not going to eat it, or maybe end up throwing it in the trash.” | |

| P2: “I know the [chayote] in the corner, it might not have a lot of nutrition, but you can’t really find it here. It’s appropriate for my culture. I know everything, I use everything, mostly daily.” | ||

| F/V commonly used in shakes, smoothies, or soups. | P3: “I like to make the shakes with spinach or fruits.” | |

| P7: “...The carrot, and the spinach and even kale or oranges– I have made shakes or juices, and I put cucumbers [too].” | ||

| Barriers to access F/V in order include time, money, transportation, and living alone. | Time: Participants spend 20 min and up to 1 h preparing food. | P7: “I have medical appointments. Sometimes I come back home tired and I lay down. Sometimes I eat something. There have been occasions where I rest, and then I go pick my daughter up. I leave early to work, really tired, and I eat at 9 pm. It depends on my routine. When I have appointments, it’s hard with time and the location. The appointments are lengthy. I don’t have a specific time to eat.” |

| P6: “I don’t have too much time, I use the microwave as much as possible, I try to do it 15, 20 min and that’s it or less, I’m always in a rush.” | ||

| Money: Groceries are expensive, particularly F/V. | P10: “Since I’m looking for a job, I try to keep calm, but I don’t think too much. I won’t die of hunger, there’s a lot of water, with water one can maintain.” | |

| P5: “If there was a better price, I could buy them more because sometimes income is a little bit limited. Sometimes at home there isn’t much to eat but vegetables and a little bit of meat or a small piece of chorizo or an egg and [the kids] whine. So, I try to buy a piece of [meat] and either rice or beans and a little bit of lettuce salad with slices of tomato, and onions, which would be the most common. I try to make all of that but I can’t buy all the fruit or the vegetables.” | ||

| P2: “What would help me eat more fruits and vegetables? Money.” | ||

| Transportation: A lack of access to transportation is a barrier to obtaining F/V. | P1: “My children are the ones that take me and bring me to doctor appointments. They work, and I work on the weekdays.” | |

| Living alone is a potential risk factor of cooking less. | P11: “I don’t make a lot of elaborate food, only when my kids come over, I make them something special. For me I try to make my foods practical, not really elaborate, but simple so that it’s good.” | |

| P1: “I live alone and I battle a lot to bring the things.” | ||

| Staple food items identified as central. | Onions, garlic, rice, beans, and cilantro are important staples. | P12: “Onions—because it isn’t typical to cook the other foods in the boxes without onions. You need onions.” |

| P6: “We use onions, that’s missing there” | ||

| P4: “The rice—I use it daily; my kids eat rice every day. Beans—well every week, or all the items every week.” | ||

| Canned items are not a top preference, except for beans, which have a mixed preference in terms of dried versus canned beans. | P5: “Because we consume tortillas, for the beans we consume them as canned and also cook them. The rice is also a base food because you accompany it with meats, sometimes with beans or eggs. So as much as the beans, for us, it’s a compliment that doesn’t miss, it’s to eat every day.” | |

| P6: “I don’t cook much of the beans, if I eat it, I eat it from the cans.” | ||

| P11: “Yes, I like the beans in the bag, so I can cook them here at home.” | ||

| Variable degrees of health literacy are present. | Cooking literacy among the population is high. | P11: “I like to cook a lot, and I know how to do a lot of things with the vegetables.” |

| Awareness of how to manage chronic diseases and how certain foods, including cultural dishes or sugar, may impact disease management. | P9: “...I buy them usually—vegetables and the fruits for the kids, and the vegetables so I can eat them for my diabetes. Now I’m doing that because before I didn’t use to eat them.” | |

| P10: “Look tortillas, rice and beans would be good, because there is a mix, a lot of tortillas I haven’t eaten since I joined [the clinic]. What I thought was good for me was not, now I eat a little bit of tortillas, rice and beans are good.” | ||

| P10: “I eat green beans as well, and mushrooms as well. That’s why my levels went down, I used to be very bad, and now not as bad.” | ||

| P5: “Piloncillo [Panela, whole cane sugar] but since I’m diabetic and I can’t eat it I prepare it in the oven, or boiled, and I put some sugar or milk, Nestle, and a bit of cheese and we eat it as if it was bread.” | ||

| Individuals are resourceful. | P12: “For me the food would not get spoiled. We would eat it, you know. I know how important it is. And I use so many of these to blend or juice. So, nothing would get spoiled—it has to get into my system.” | |

| P7: “Sometimes I make juices in the blender, using sweet potatoes, and honey they’re good, better than the carrot ones. If I don’t have, and I only have carrot, then I make it with carrots, if I have celery then I only use celery.” | ||

| P13: “...Everything that’s in there I would eat because I won’t waste food.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crusan, A.; Roozen, K.; Godoy-Henderson, C.; Zamarripa, K.; Remache, A. Using Community-Based Participatory Research Methods to Inform the Development of Medically Tailored Food Kits for Hispanic/Latine Adults with Hypertension: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163600

Crusan A, Roozen K, Godoy-Henderson C, Zamarripa K, Remache A. Using Community-Based Participatory Research Methods to Inform the Development of Medically Tailored Food Kits for Hispanic/Latine Adults with Hypertension: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(16):3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163600

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrusan, Ambria, Kerrie Roozen, Clara Godoy-Henderson, Kathy Zamarripa, and Anayeli Remache. 2023. "Using Community-Based Participatory Research Methods to Inform the Development of Medically Tailored Food Kits for Hispanic/Latine Adults with Hypertension: A Qualitative Study" Nutrients 15, no. 16: 3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163600

APA StyleCrusan, A., Roozen, K., Godoy-Henderson, C., Zamarripa, K., & Remache, A. (2023). Using Community-Based Participatory Research Methods to Inform the Development of Medically Tailored Food Kits for Hispanic/Latine Adults with Hypertension: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients, 15(16), 3600. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15163600