Does Pizza Consumption Favor an Improved Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Selection of Participants and Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population Characteristics: Most Females in Remission or with Low Disease Activity

3.2. Summary Statistics of Consumption Frequencies of Pizza and Related Food Items/Group: Low Percentages of Non-Consumers, Differences in Summary Statistics between Overall Sample and Strata for All Investigated Variables, Except for Refined Grains

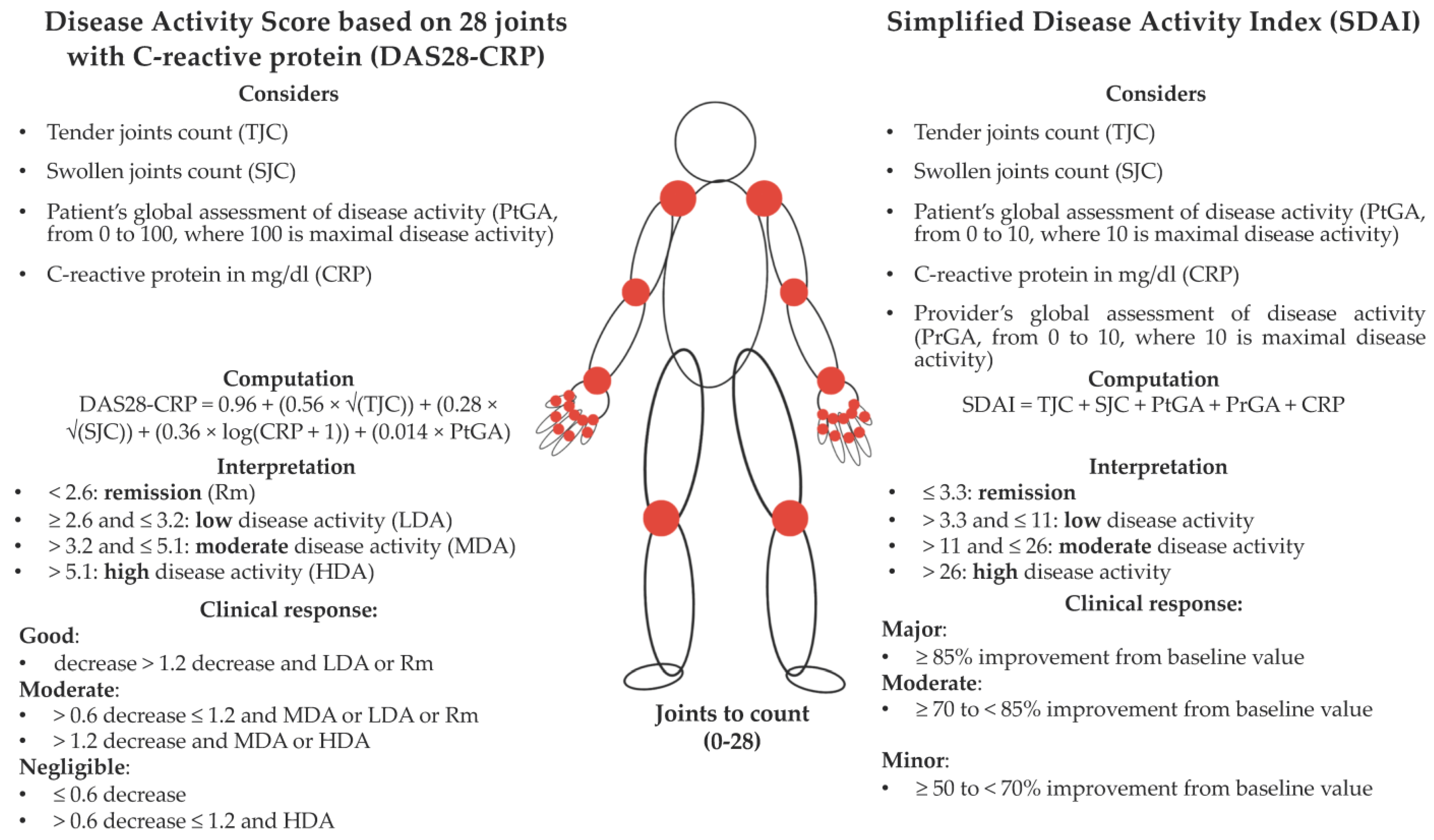

3.3. Beneficial Effect (the DAS28-CRP and SDAI), Mostly Significant, in the Highest Tertile Category of Pizza Consumption

3.4. Strata by Disease Severity: Stronger Beneficial Effect (the DAS28-CRP and SDAI), Mostly Significant, in the Highest Tertile Category of Pizza Consumption, for the More Severe Stratum, Mirrored in Part by Mozzarella Cheese and Olive Oil

3.5. Strata by Disease Duration: Beneficial Effect (DAS28-CRP and SDAI) in the Highest-Tertile Category of Consumption of Pizza and Mozzarella Cheese, for the Longer-Duration Stratum, within a General Framework of Non-Significant Findings

4. Discussion

- (1)

- Pizza is generally intended as a stand-alone single-item meal in Italy, where typically no small, medium, or large size variants of pizza are served; RA patients can buy one pizza and, in this way, easily solve lunch/dinner cooking issues.

- (2)

- Despite their high-quality ingredients, 96% of Italian takeout or restaurant pizzas currently cost between 5 and 10 euros [74]; eating a pizza once a week is therefore widely affordable, especially when compared to other foods, such as oily fish, walnuts, and seeds, or dietary supplements, such as omega-3 fatty acids, which are typically suggested to integrate the diet of RA patients [20].

- (1)

- Italian pizza’s composition generally balances carbohydrates, proteins, and fats well [39]. Should further evidence support our claim of improved RA activity with increased pizza consumption, nutritionists may suggest that RA patients eat pizza as a stand-alone meal more than once a week, while taking care not to exceed the suggested dietary target for sodium intake [69], which is easily reached through pizza consumption [39,76].

- (2)

- (3)

- In Italian pizza, not only does the emulsion of oil with tomato sauce before the cooking phase contribute to the uniform cooking of the ingredients [28], but it generally enhances the pizza’s antioxidant potential, including the content of phenolic compounds and lycopene, the Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity, and the bio-accessibility of phenolic compounds and lycopene [77]. Concerning oil, the higher-quality oil (e.g., olive oil or even extra-virgin olive oil), which is mandatory in Neapolitan Pizza TSG [28,29], provides greater resistance to heating-related lipid oxidation due to the higher presence of bioactive compounds such as polyphenols [80,81,82,83,84]. Concerning tomato sauce, which is mandatory in Neapolitan Pizza TSG [28,29], the formation of micelles with oil lipids facilitates lycopene release, following the initial heating-related partial breaking of the cell-wall membrane [77,85], thus increasing lycopene bio-accessibility. Finally, extra-virgin olive oil offers a suitable environment for the isomerization of lycopene, with the formed Z-isomers outperforming E-isomers in absorption, transport flexibility, and antioxidant capacity [77,86].

- (4)

- Jointly with its antioxidant potential [77], the anti-inflammatory potential of Italian pizza may be another important mechanism of action. An increasing amount of evidence points to a beneficial effect, if any, of dairy products and dairy proteins on the biomarkers of inflammation [87,88], meaning that mozzarella cheese may exert intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity. In addition, cheese may counteract the glycemic response from the dough-related carbohydrate load [89], thanks to the presence of high-biological-value dairy proteins [69]. As an example, the Neapolitan pizza TSG requires 80 to 100 g of mozzarella on each pizza base, which corresponds to ~15–19 g of high-biological-value dairy proteins per pizza [28,29,39]. This may be particularly important when mozzarella on pizza is preferred to pro-inflammatory protein sources, such as processed meat [90], thus also exerting its anti-inflammatory effect through substitution.

- (5)

- Finally, pizza might be thought a general indicator of a healthy, varied Italian diet, a variant of the Mediterranean diet that includes a higher consumption of pasta compared to other countries on the Mediterranean basin [34]. Although pizza itself does not, each of the single food items/groups investigated belongs to the definition of the Mediterranean diet [34]. The well-known anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of which have the potential to modulate inflammatory pathways in RA, and to benefit the gut microbiota [91,92,93]. These properties may be one of the reasons why, among European countries, Italy is in the top ten in terms of life expectancy at birth in 2021 (82.7 years) [94]. However, when adherence to the Mediterranean diet itself [95] was considered in relation to the DAS28-CRP or SDAI in a subset of the current sample, the results were materially null [58]. This similarly happened in two other observational studies from Greece [96] and Japan [97], assessing a potential association between dietary habits and disease activity although, in the latter [97], single components of the Mediterranean diet exerted some beneficial effect. Whether this was due to the difficulty in capturing the expected small effects of dietary habits in observational studies on RA activity, methodological issues in the study design/implementation, or other reasons, is still a matter of debate [20]. However, while we are observing a shift toward more motivated patients, engaged in the self-management of their disease, large and well-conducted cohort studies that consider reproducible and valid tools for diet assessment, internationally recognized measures of RA activity, and an appropriately wide set of confounding factors are urgently needed to draw firm conclusions on the role of diet in RA management [20]. This evidence will be integrated with that from dietary intervention trials in RA (see Philippou et al., 2021 [98], for an updated systematic review on the topic), where larger and longer-duration intervention studies are still needed, although the evidence of a beneficial effect of an anti-inflammatory Mediterranean diet in RA management seems stronger [20].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Testa, D.; Calvacchi, S.; Petrelli, F.; Giannini, D.; Bilia, S.; Alunno, A.; Puxeddu, I. One year in review 2021: Pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutairi, K.B.; Nossent, J.C.; Preen, D.B.; Keen, H.I.; Inderjeeth, C.A. The Prevalence of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review of Population-based Studies. J. Rheumatol. 2021, 48, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, M.; Rossi, E.; Bernardi, D.; Viapiana, O.; Gatti, D.; Idolazzi, L.; Caimmi, C.; Derosa, M.; Adami, S. Prevalence and incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. Rheumatol. Int. 2014, 34, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, M.A.; Parisi, M.; Moggiana, G.; Mela, G.S.; Accardo, S. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Italy: The Chiavari Study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1998, 57, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, G.; Jing, Z.; Lv, L.; Nan, K.; Dang, X. The Burden of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Findings from the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases Study and Forecasts for 2030 by Bayesian Age-Period-Cohort Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, K.; Bergman, S.; Andersson, M.L.; Bremander, A.; Larsson, I. Quality of life in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis: A phenomenographic study. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5, 2050312117713647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, A.F.; Bungau, S.G. Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Overview. Cells 2021, 10, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, A. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Common Questions About Diagnosis and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2018, 97, 455–462. [Google Scholar]

- Smolen, J.S.; Breedveld, F.C.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.; Dougados, M.; Emery, P.; Kvien, T.K.; Navarro-Compan, M.V.; Oliver, S.; Schoels, M.; et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewe, R.B.M.; Bergstra, S.A.; Kerschbaumer, A.; Sepriano, A.; Aletaha, D.; Caporali, R.; Edwards, C.J.; Hyrich, K.L.; Pope, J.E.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2023, 82, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.; Roodenrijs, N.M.T.; Welsing, P.M.; Kedves, M.; Hamar, A.; van der Goes, M.C.; Kent, A.; Bakkers, M.; Blaas, E.; Senolt, L.; et al. EULAR definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewe, R.B.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Kerschbaumer, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Sepriano, A.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; de Wit, M.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewe, R.; Breedveld, F.C.; Buch, M.; Burmester, G.; Dougados, M.; Emery, P.; Gaujoux-Viala, C.; Gossec, L.; Nam, J.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 492–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, J.; Upchurch, K.S. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology 2012, 51 (Suppl. S6), vi5–vi9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgers, L.E.; Raza, K.; van der Helm-van Mil, A.H. Window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis-definitions and supporting evidence: From old to new perspectives. RMD Open 2019, 5, e000870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingegnoli, F.; Schioppo, T.; Ubiali, T.; Bollati, V.; Ostuzzi, S.; Buoli, M.; Caporali, R. Relevant non-pharmacologic topics for clinical research in rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases: The patient perspective. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 1305–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, G.; Viapiana, O.; Rossini, M.; Orsolini, G.; Bertoldo, E.; Giollo, A.; Gatti, D.; Fassio, A. Association between environmental air pollution and rheumatoid arthritis flares. Rheumatology 2021, 60, 4591–4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelman, L.; Egea Rodrigues, C.; Aleksandrova, K. Effects of Dietary Patterns on Biomarkers of Inflammation and Immune Responses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, C.; Keysser, G. Lifestyle Factors and Their Influence on Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 7179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikiphorou, E.; Philippou, E. Nutrition and its role in prevention and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edefonti, V.; Parpinel, M.; Ferraroni, M.; Boracchi, P.; Schioppo, T.; Scotti, I.; Ubiali, T.; Currenti, W.; De Lucia, O.; Cutolo, M.; et al. A Posteriori Dietary Patterns and Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity: A Beneficial Role of Vegetable and Animal Unsaturated Fatty Acids. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkiouras, K.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Myrogiannis, I.; Papamitsou, T.; Rigopoulou, E.I.; Sakkas, L.I.; Bogdanos, D.P. Efficacy of n-3 fatty acid supplementation on rheumatoid arthritis’ disease activity indicators: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raad, T.; Griffin, A.; George, E.S.; Larkin, L.; Fraser, A.; Kennedy, N.; Tierney, A.C. Dietary Interventions with or without Omega-3 Supplementation for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, S.; Jaiswal, K.S.; Gupta, B. Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis with Dietary Interventions. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, S.K.; Bathon, J.M.; Giles, J.T.; Lin, T.C.; Yoshida, K.; Solomon, D.H. Relationship Between Fish Consumption and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoldstam, L.; Hagfors, L.; Johansson, G. An experimental study of a Mediterranean diet intervention for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003, 62, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vito, R.; Fiori, F.; Ferraroni, M.; Cavalli, S.; Caporali, R.; Ingegnoli, F.; Parpinel, M.; Edefonti, V. Olive Oil and Nuts in Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity. Nutrients 2023, 15, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana (AVPN) International Regulation-Regulations for Obtaining Use of the Collective Trade Mark “Verace Pizza Napoletana” (Vera Pizza Napoletana). Available online: https://www.pizzanapoletana.org/public/pdf/Disciplinare_AVPN_2022_en.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Official Journal of the European Union-COMMISSION REGULATION (EU) No 97/2010 of 4 February 2010 Entering a Name in the Register of Traditional Specialities Guaranteed [Pizza Napoletana (TSG)]. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2010/97/oj (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Coldiretti-Pizza Day: È fai da te per 4 Italiani su 10. Available online: https://www.coldiretti.it/consumi/pizza-day-e-fai-da-te-per-4-italiani-su-10 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Gallus, S.; Bosetti, C.; Negri, E.; Talamini, R.; Montella, M.; Conti, E.; Franceschi, S.; La Vecchia, C. Does pizza protect against cancer? Int. J. Cancer 2003, 107, 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallus, S.; Talamini, R.; Bosetti, C.; Negri, E.; Montella, M.; Franceschi, S.; Giacosa, A.; La Vecchia, C. Pizza consumption and the risk of breast, ovarian and prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2006, 15, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallus, S.; Tavani, A.; La Vecchia, C. Pizza and risk of acute myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallus, S.; Bosetti, C.; La Vecchia, C. Mediterranean diet and cancer risk. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2004, 13, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centonze, S.; Boeing, H.; Leoci, C.; Guerra, V.; Misciagna, G. Dietary habits and colorectal cancer in a low-risk area. Results from a population-based case-control study in southern Italy. Nutr. Cancer 1994, 21, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, H.D.; Liu, S.; Gaziano, J.M.; Buring, J.E. Dietary lycopene, tomato-based food products and cardiovascular disease in women. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 2336–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sesso, H.D.; Wang, L.; Ridker, P.M.; Buring, J.E. Tomato-based food products are related to clinically modest improvements in selected coronary biomarkers in women. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannucci, E.; Ascherio, A.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Willett, W.C. Intake of carotenoids and retinol in relation to risk of prostate cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995, 87, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnagnarella, P.; Parpinel, M.; Salvini, S. Banca Dati di Composizione degli Alimenti per Studi Epidemiologici in Italia; libreriauniversitaria.it Edizioni: Padova, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ANSA-Crisi: Pizza e Birra, ‘rito’ Resiste ma 58% Ordina a Casa. Available online: https://www.ansa.it/terraegusto/notizie/rubriche/prodtipici/2014/11/06/crisi-pizza-e-birrarito-resiste-ma-58-ordina-a-casa_d4f2f4dd-10e5-4660-ac7a-b0a6fc4c7e2c.html (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Confederazione Nazionale dell’Artigianato e della Piccola e Media Impresa (CNA)-Dati Pizza di Sintesi 2021. Available online: https://www.cna.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Pizza-2021-Dati-sintesi-e-confronto.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Varraso, R.; Kauffmann, F.; Leynaert, B.; Le Moual, N.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Romieu, I. Dietary patterns and asthma in the E3N study. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggio, R.; Elorriaga, N.; Gutierrez, L.; Irazola, V.; Rubinstein, A.; Danaei, G. Associations between dietary patterns and serum lipids, apo and C-reactive protein in an adult population: Evidence from a multi-city cohort in South America. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ollberding, N.J.; Aschebrook-Kilfoy, B.; Caces, D.B.; Smith, S.M.; Weisenburger, D.D.; Chiu, B.C. Dietary patterns and the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, S.E.; Gutierrez, O.M.; Newby, P.K.; Howard, G.; Howard, V.J.; Locher, J.L.; Kissela, B.M.; Shikany, J.M. Dietary patterns are associated with incident stroke and contribute to excess risk of stroke in black Americans. Stroke 2013, 44, 3305–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaillzadeh, A.; Kimiagar, M.; Mehrabi, Y.; Azadbakht, L.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Dietary patterns and markers of systemic inflammation among Iranian women. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Bonanni, A.E.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; De Lucia, F.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Moli-sani Project, I. Low income is associated with poor adherence to a Mediterranean diet and a higher prevalence of obesity: Cross-sectional results from the Moli-sani study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e001685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Bonanni, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Lucia, F.; Pounis, G.; Zito, F.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with a better health-related quality of life: A possible role of high dietary antioxidant content. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Lucia, F.; Olivieri, M.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Bonanni, A. Mass media information and adherence to Mediterranean diet: Results from the Moli-sani study. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; De Lucia, F.; Olivieri, M.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; Bonanni, A.; Moli-sani Project, I. Nutrition knowledge is associated with higher adherence to Mediterranean diet and lower prevalence of obesity. Results from the Moli-sani study. Appetite 2013, 68, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Persichillo, M.; De Curtis, A.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L.; On Behalf of The MOLI-SANI Study Investigators. Adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet and mortality in subjects with diabetes. Prospective results from the MOLI-SANI study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Pounis, G.; Persichillo, M.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Mediterranean-type diet is associated with higher psychological resilience in a general adult population: Findings from the Moli-sani study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanni, A.E.; Bonaccio, M.; di Castelnuovo, A.; de Lucia, F.; Costanzo, S.; Persichillo, M.; Zito, F.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Food labels use is associated with higher adherence to Mediterranean diet: Results from the Moli-sani study. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4364–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centritto, F.; Iacoviello, L.; di Giuseppe, R.; De Curtis, A.; Costanzo, S.; Zito, F.; Grioni, S.; Sieri, S.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; et al. Dietary patterns, cardiovascular risk factors and C-reactive protein in a healthy Italian population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 19, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maugeri, A.; Barchitta, M.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Agodi, A. Maternal Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Pre-Pregnancy Body Mass Index and Gestational Weight Gain: Results from the “Mamma & Bambino” Cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchitta, M.; Maugeri, A.; Magnano San Lio, R.; Favara, G.; La Rosa, M.C.; La Mastra, C.; Quattrocchi, A.; Agodi, A. Dietary Patterns are Associated with Leukocyte LINE-1 Methylation in Women: A Cross-Sectional Study in Southern Italy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitnux-The Most Surprising Pizza Consumption Statistics and Trends in 2023. Available online: https://blog.gitnux.com/pizza-consumption-statistics/ (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Ingegnoli, F.; Schioppo, T.; Scotti, I.; Ubiali, T.; De Lucia, O.; Murgo, A.; Marano, G.; Boracchi, P.; Caporali, R. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and patient perception of rheumatoid arthritis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 52, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, F.C.; Edworthy, S.M.; Bloch, D.A.; McShane, D.J.; Fries, J.F.; Cooper, N.S.; Healey, L.A.; Kaplan, S.R.; Liang, M.H.; Luthra, H.S.; et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletaha, D.; Neogi, T.; Silman, A.J.; Funovits, J.; Felson, D.T.; Bingham, C.O., 3rd; Birnbaum, N.S.; Burmester, G.R.; Bykerk, V.P.; Cohen, M.D.; et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marventano, S.; Mistretta, A.; Platania, A.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Reliability and relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire for Italian adults living in Sicily, Southern Italy. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 67, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consiglio per la Ricerca in Agricoltura e l’Analisi dell’Economia Agraria (CREA)-Tabelle di Composizione degli Alimenti. Formerly. Available online: http://nut.entecra.it/646/tabelle_di_composizione_degli_alimenti.html (accessed on 30 June 2015).

- Haytowitz, D.; Ahuja, J.; Wu, X.; Khan, M.; Somanchi, M.; Nickle, M.; Nguyen, Q.; Roseland, J.; Williams, J.; Patterson, K. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Legacy; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Willett, W. Nutritional Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fransen, J.; van Riel, P.L. The Disease Activity Score and the EULAR response criteria. Rheum. Dis. Clin. 2009, 35, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, J.; Creemers, M.C.; Van Riel, P.L. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: Agreement of the disease activity score (DAS28) with the ARA preliminary remission criteria. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 1252–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D. Scores for all seasons: SDAI and CDAI. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2014, 32, S75–S79. [Google Scholar]

- Yohai, V.J. High breakdown-point and high efficiency robust estimates for regression. Ann. Stat. 1987, 15, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SINU. Livelli di Assunzione di Riferimento di Nutrienti ed Energia per la Popolazione Italiana (LARN)—IV Revisione; SICS: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: http://www.R-project.org (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Ripley, B.; Venables, B.; Bates, D.; Hornik, K.; Gebhardt, A.; Firth, D.; Ripley, M. Package ‘mass’. CRAN R 2013, 538, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mächler, M.; Ruckstuhl, A. Robust Statistics Collaborative Package Development: ‘Robustbase’. Book of Abstracts. 2006. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/nosvn/conferences/useR-2006/Slides/Maechler+Ruckstuhl.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Dragulescu, A.; Arendt, C. xlsx: Read, Write, Format Excel 2007 and Excel 97/2000/XP/2003 Files. R package version 0.6.5. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=xlsx (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- WineNews-Tutti i Numeri della Pizza, Settore da 15 Miliardi di Fatturato: Se ne Sfornano 8 Milioni al Giorno. Available online: https://winenews.it/it/tutti-i-numeri-della-pizza-settore-da-15-miliardi-di-fatturato-se-ne-sfornano-8-milioni-al-giorno_463801/ (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Combet, E.; Jarlot, A.; Aidoo, K.E.; Lean, M.E. Development of a nutritionally balanced pizza as a functional meal designed to meet published dietary guidelines. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2577–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassy, M.; Rytz, A.; Drewnowski, A.; Lecat, A.; Jacquier, E.F.; Charles, V.R. Monitoring improvements in the nutritional quality of new packaged foods launched between 2016 and 2020. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 983940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, I.; Izzo, L.; Graziani, G.; Ritieni, A. The Nutraceutical Properties of “Pizza Napoletana Marinara TSG” a Traditional Food Rich in Bioaccessible Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscopo, A.; Zappia, A.; Mincione, A.; Silletti, R.; Summo, C.; Pasqualone, A. Effect of Oil Type Used in Neapolitan Pizza TSG Topping on Its Physical, Chemical, and Sensory Properties. Foods 2022, 12, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongpiya, J.; Charoenngam, N.; Ponvilawan, B.; Yingchoncharoen, P.; Jaroenlapnopparat, A.; Ungprasert, P. Increased Prevalence of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Among Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obied, H.K. Biography of biophenols: Past, present and future. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2013, 3, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, M.C.; Tome-Carneiro, J.; Davalos, A.; Visioli, F. Pharma-Nutritional Properties of Olive Oil Phenols. Transfer of New Findings to Human Nutrition. Foods 2018, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrouk, A.; Martine, L.; Gregoire, S.; Nury, T.; Meddeb, W.; Camus, E.; Badreddine, A.; Durand, P.; Namsi, A.; Yammine, A.; et al. Profile of Fatty Acids, Tocopherols, Phytosterols and Polyphenols in Mediterranean Oils (Argan Oils, Olive Oils, Milk Thistle Seed Oils and Nigella Seed Oil) and Evaluation of their Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Activities. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1791–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Alzaa, F.; Guillaume, C.; Ravetti, L. Evaluation of chemical and physical changes in different commercial oils during heating. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2018, 2, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Saleh, A.S.; Chen, J.; Shen, Q. Chemical alterations taken place during deep-fat frying based on certain reaction products: A review. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2012, 165, 662–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.E.; Buchowski, M.S.; Liu, J.; Schlundt, D.G.; Ukoli, F.A.; Blot, W.J.; Hargreaves, M.K. Plasma Lycopene Is Associated with Pizza and Pasta Consumption in Middle-Aged and Older African American and White Adults in the Southeastern USA in a Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Gleize, B.; Zhang, L.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Renard, C. A D-optimal mixture design of tomato-based sauce formulations: Effects of onion and EVOO on lycopene isomerization and bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3589–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, K.M.; Anderson, B.D.; Cifelli, C.J. The Effects of Dairy Product and Dairy Protein Intake on Inflammation: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2021, 40, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Laudisio, D.; Frias-Toral, E.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. Anti-Inflammatory Nutrients and Obesity-Associated Metabolic-Inflammation: State of the Art and Future Direction. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, B.; Anderson, G.H.; Pare, S.; Tucker, A.J.; Vien, S.; Wright, A.J.; Goff, H.D. Effect of milk protein intake and casein-to-whey ratio in breakfast meals on postprandial glucose, satiety ratings, and subsequent meal intake. J. Dairy. Sci. 2018, 101, 8688–8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiraseb, F.; Hosseininasab, D.; Mirzababaei, A.; Bagheri, R.; Wong, A.; Suzuki, K.; Mirzaei, K. Red, white, and processed meat consumption related to inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers among overweight and obese women. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1015566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, C.; Lucchino, B.; Tarsitano, M.G.; Iannuccelli, C.; Di Franco, M. Dietary Habits and Nutrition in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Can Diet Influence Disease Development and Clinical Manifestations? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourado, E.; Ferro, M.; Sousa Guerreiro, C.; Fonseca, J.E. Diet as a Modulator of Intestinal Microbiota in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badsha, H. Role of Diet in Influencing Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity. Open. Rheumatol. J. 2018, 12, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat-Life Expectancy at Birth by Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TPS00205/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Pitsavos, C.; Stefanadis, C. Dietary patterns: A Mediterranean diet score and its relation to clinical and biological markers of cardiovascular disease risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2006, 16, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linos, A.; Kaklamanis, E.; Kontomerkos, A.; Koumantaki, Y.; Gazi, S.; Vaiopoulos, G.; Tsokos, G.C.; Kaklamanis, P. The effect of olive oil and fish consumption on rheumatoid arthritis—A case control study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1991, 20, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Sugioka, Y.; Tada, M.; Okano, T.; Mamoto, K.; Inui, K.; Habu, D.; Koike, T. Monounsaturated fatty acids might be key factors in the Mediterranean diet that suppress rheumatoid arthritis disease activity: The TOMORROW study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 675–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippou, E.; Petersson, S.D.; Rodomar, C.; Nikiphorou, E. Rheumatoid arthritis and dietary interventions: Systematic review of clinical trials. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analyses | Total | Pizza | Refined Grains | Mozzarella Cheese | Olive Oil | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | n = 365 | n (%) non-consumers | 37 (10.14%) | 5 (1.37%) | 43 (11.78%) | 17 (4.66%) | |

| median (I–III quartile) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 1.785 (1.142–2.785) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 1.000 (1.000–3.000) | |||

| mean (SD) | 0.107 (0.110) | 2.030 (1.273) | 0.159 (0.179) | 1.868 (1.111) | |||

| Severity | RF- and/or ACPA-positive | n = 223 | n (%) non-consumers | 23 (10.31%) | 1 (0.45%) | 26 (11.66%) | 11 (4.93%) |

| median (I–III quartile) | 0.065 (0.032–0.142) | 1.785 (1.158–2.749) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 1.000 (1.000–3.000) | |||

| mean (SD) | 0.103 (0.105) | 1.954 (1.061) | 0.160 (0.191) | 1.791 (1.118) | |||

| RF- and ACPA-negative | n = 142 | n (%) non-consumers | 14 (9.86%) | 4 (2.82%) | 17 (11.97%) | 6 (4.23%) | |

| median (I–III quartile) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 1.798 (1.141–3.000) | 0.142 (0.065–0.142) | 3.000 (1.000–3.000) | |||

| mean (SD) | 0.115 (0.117) | 2.149 (1.546) | 0.157 (0.161) | 1.989 (1.094) | |||

| Duration | Disease duration > 15 years | n = 154 | n (%) non-consumers | 16 (10.39%) | 3 (1.95%) | 21 (13.64%) | 5 (3.25%) |

| median (I–III quartile) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 1.714 (1.137–2.808) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 3.000 (1.000–3.000) | |||

| mean (SD) | 0.111 (0.133) | 2.001 (1.288) | 0.152 (0.171) | 1.977 (1.100) | |||

| Disease duration ≤ 15 years | n = 211 | n (%) non-consumers | 21 (9.95%) | 2 (0.95%) | 22 (10.43%) | 12 (5.69%) | |

| median (I–III quartile) | 0.142 (0.032–0.142) | 1.915 (1.190–2.714) | 0.142 (0.065–0.142) | 1.000 (1.000–3.000) | |||

| mean (SD) | 0.105 (0.089) | 2.051 (1.265) | 0.164 (0.185) | 1.789 (1.116) |

| Overall Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | |||||

| Food Items/Group | Tertile Categories | Number of Subjects in Remission/Active RA | OR | 95% CI | |

| DAS28-CRP | |||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 101/59 | 0.821 | 0.484 | 1.391 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 14/3 | 0.252 | 0.062 | 1.028 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 66/47 | 1.900 | 1.002 | 3.602 |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 76/42 | 1.135 | 0.550 | 2.344 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 93/58 | 0.852 | 0.496 | 1.465 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 46/18 | 0.490 | 0.236 | 1.018 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 112/60 | 0.729 | 0.443 | 1.201 |

| SDAI | |||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 52/108 | 0.484 | 0.269 | 0.870 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 7/10 | 0.274 | 0.079 | 0.952 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 32/81 | 0.641 | 0.313 | 1.315 |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 39/79 | 0.489 | 0.224 | 1.068 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 40/111 | 0.788 | 0.423 | 1.466 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 27/37 | 0.321 | 0.151 | 0.683 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 49/123 | 0.993 | 0.575 | 1.715 |

| Robust linear regression | |||||

| Food items/group | Tertile categories | Number of subjects | Beta | SE | p-value |

| DAS28-CRP | |||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 116 | −0.356 | 0.157 | 0.024 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 12 | −0.730 | 0.350 | 0.044 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 80 | 0.168 | 0.145 | 0.251 |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 73 | −0.051 | 0.162 | 0.754 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 102 | −0.045 | 0.159 | 0.782 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 38 | −0.362 | 0.213 | 0.087 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 118 | −0.201 | 0.146 | 0.171 |

| SDAI | |||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 160 | −1.302 | 0.683 | 0.056 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 17 | −3.587 | 1.537 | 0.021 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 113 | 0.541 | 0.838 | 0.525 |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 118 | −0.469 | 0.935 | 0.617 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 151 | 0.294 | 0.723 | 0.688 |

| III (0.142; 1] | 64 | −1.372 | 0.919 | 0.135 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 172 | −0.865 | 0.654 | 0.190 |

| RF- and/or ACPA-Positive | RF- and ACPA-Negative | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | ||||||||||

| Food Items/Groups | Tertile Categories | Number of Subjects in Remission/ Active RA | OR | 95% CI | Number of Subjects in Remission/ Active RA | OR | 95% CI | phetero 3 | ||

| DAS28-CRP | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 58/28 | 0.435 | 0.211 | 0.897 | 43/31 | 2.397 | 0.854 | 6.733 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 9/3 | 0.195 | 0.039 | 0.969 | 5/0 | NE | NE | NE | 0.001 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 45/30 | 1.741 | 0.757 | 4.006 | 21/17 | 1.767 | 0.543 | 5.745 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 42/26 | 1.115 | 0.437 | 2.846 | 34/16 | 1.319 | 0.360 | 4.829 | 0.788 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 57/33 | 0.682 | 0.328 | 1.420 | 36/25 | 2.018 | 0.729 | 5.581 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 25/12 | 0.369 | 0.141 | 0.968 | 21/6 | 0.931 | 0.241 | 3.603 | 0.234 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 67/32 | 0.537 | 0.269 | 1.071 | 45/28 | 1.216 | 0.449 | 3.288 | 0.114 |

| SDAI | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 33/53 | 0.204 | 0.087 | 0.478 | 19/55 | 1.808 | 0.579 | 5.645 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 4/8 | 0.161 | 0.032 | 0.825 | 3/2 | 0.333 | 0.021 | 5.228 | 0.020 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 21/54 | 0.814 | 0.326 | 2.033 | 11/27 | 0.479 | 0.117 | 1.965 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 21/47 | 0.546 | 0.200 | 1.492 | 18/32 | 0.350 | 0.076 | 1.616 | 0.838 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 27/63 | 0.576 | 0.242 | 1.370 | 13/48 | 1.968 | 0.643 | 6.026 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 15/22 | 0.200 | 0.068 | 0.586 | 12/15 | 0.645 | 0.168 | 2.470 | 0.283 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 33/66 | 0.567 | 0.267 | 1.202 | 16/57 | 4.075 | 1.263 | 13.147 | 0.008 |

| Robust linear regression | ||||||||||

| Food items/groups | Tertile categories | Number of subjects | Beta | SE | p-value | Number of subjects | Beta | SE | p-value | phetero 3 |

| DAS28-CRP | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 86 | −0.584 | 0.163 | <0.001 | 74 | 0.196 | 0.178 | 0.271 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 12 | −0.675 | 0.341 | 0.052 | 5 | −0.379 | 0.424 | 0.358 | 0.001 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 75 | 0.349 | 0.200 | 0.086 | 38 | −0.117 | 0.211 | 0.580 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 68 | 0.017 | 0.223 | 0.941 | 50 | −0.159 | 0.233 | 0.499 | 0.970 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 90 | −0.261 | 0.181 | 0.154 | 61 | 0.235 | 0.179 | 0.192 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 37 | −0.573 | 0.230 | 0.013 | 27 | 0.020 | 0.229 | 0.931 | 0.164 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 99 | −0.371 | 0.161 | 0.023 | 73 | 0.114 | 0.181 | 0.527 | 0.126 |

| SDAI | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 86 | −3.232 | 0.980 | 0.001 | 74 | 1.243 | 1.130 | 0.271 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 12 | −5.279 | 2.053 | 0.012 | 5 | −1.877 | 2.688 | 0.471 | <0.001 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 75 | 1.342 | 1.118 | 0.240 | 38 | −0.733 | 1.324 | 0.584 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 68 | 0.184 | 1.246 | 0.883 | 50 | −1.970 | 1.465 | 0.185 | 0.941 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 90 | −0.475 | 1.041 | 0.657 | 61 | 1.762 | 1.133 | 0.122 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 37 | −2.439 | 1.320 | 0.063 | 27 | 0.704 | 1.444 | 0.628 | <0.001 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 99 | −2.094 | 0.962 | 0.034 | 73 | −0.267 | 1.146 | 0.817 | <0.001 |

| Disease Duration >15 years | Disease Duration ≤15 years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | ||||||||||

| Food Items/Groups | Tertile Categories | Number of Subjects in Remission/ Active RA | OR | 95%CI | Number of Subjects in Remission/ Active RA | OR | 95%CI | phetero 3 | ||

| DAS28-CRP | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 39/25 | 0.55 | 0.236 | 1.28 | 62/34 | 0.971 | 0.454 | 2.081 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 8/0 | NE | NE | NE | 6/3 | 1.057 | 0.186 | 5.995 | 0.026 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 28/20 | 0.880 | 0.337 | 2.294 | 38/27 | 5.994 | 2.130 | 16.866 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 27/20 | 0.791 | 0.271 | 2.308 | 49/22 | 1.718 | 0.532 | 5.550 | 0.064 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 38/26 | 0.310 | 0.124 | 0.779 | 55/32 | 1.707 | 0.757 | 3.852 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 19/7 | 0.178 | 0.049 | 0.650 | 27/11 | 1.109 | 0.388 | 3.171 | 0.011 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 47/31 | 0.481 | 0.210 | 1.104 | 65/29 | 0.794 | 0.376 | 1.678 | 0.394 |

| SDAI | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 20/44 | 0.389 | 0.138 | 1.092 | 32/64 | 0.563 | 0.261 | 1.215 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 3/5 | 0.190 | 0.020 | 1.830 | 4/5 | 0.378 | 0.060 | 2.373 | 0.835 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 15/33 | 0.308 | 0.091 | 1.036 | 17/48 | 1.091 | 0.415 | 2.867 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 10/37 | 0.591 | 0.151 | 2.320 | 29/42 | 0.540 | 0.195 | 1.498 | 0.055 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 15/49 | 0.513 | 0.169 | 1.563 | 25/62 | 0.990 | 0.441 | 2.222 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 9/17 | 0.299 | 0.074 | 1.207 | 18/20 | 0.406 | 0.153 | 1.080 | 0.733 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 20/58 | 0.615 | 0.231 | 1.634 | 29/65 | 1.155 | 0.559 | 2.387 | 0.457 |

| Robust linear regression | ||||||||||

| Food items/groups | Tertile categories | Number of subjects | Beta | SE | p-value | Number of subjects | Beta | SE | p-value | phetero3 |

| DAS28-CRP | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 64 | −0.517 | 0.209 | 0.015 | 96 | −0.174 | 0.142 | 0.221 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 8 | −1.120 | 0.479 | 0.018 | 9 | −0.062 | 0.323 | 0.855 | 0.016 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 48 | 0.179 | 0.247 | 0.474 | 65 | 0.349 | 0.177 | 0.053 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 47 | −0.041 | 0.278 | 0.884 | 71 | 0.081 | 0.198 | 0.685 | 0.822 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 64 | −0.402 | 0.218 | 0.074 | 87 | 0.134 | 0.144 | 0.353 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 26 | −0.651 | 0.285 | 0.023 | 38 | −0.094 | 0.184 | 0.606 | 0.038 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 78 | −0.384 | 0.201 | 0.059 | 94 | −0.094 | 0.136 | 0.494 | 0.585 |

| SDAI | ||||||||||

| Pizza | II (0.065; 0.142] | 64 | −2.760 | 1.291 | 0.035 | 96 | −1.167 | 0.814 | 0.152 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 8 | −5.174 | 2.963 | 0.073 | 9 | −2.356 | 1.855 | 0.235 | <0.001 | |

| Refined grains (without pizza) | II (0.142; 2.357] | 48 | −0.251 | 1.434 | 0.864 | 65 | 2.043 | 1.056 | 0.058 | |

| III (2.357; 9.675] | 47 | −0.575 | 1.614 | 0.723 | 71 | 0.282 | 1.178 | 0.813 | <0.001 | |

| Mozzarella cheese | II (0.065; 0.142] | 64 | −1.611 | 1.296 | 0.226 | 87 | 1.243 | 0.851 | 0.148 | |

| III (0.142; 1] | 26 | −2.699 | 1.695 | 0.110 | 38 | −0.471 | 1.088 | 0.667 | <0.001 | |

| Olive oil 2 | II (1; 3] | 78 | −2.193 | 1.202 | 0.073 | 94 | −0.196 | 0.781 | 0.806 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Vito, R.; Parpinel, M.; Speciani, M.C.; Fiori, F.; Bianco, R.; Caporali, R.; Ingegnoli, F.; Scotti, I.; Schioppo, T.; Ubiali, T.; et al. Does Pizza Consumption Favor an Improved Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis? Nutrients 2023, 15, 3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153449

De Vito R, Parpinel M, Speciani MC, Fiori F, Bianco R, Caporali R, Ingegnoli F, Scotti I, Schioppo T, Ubiali T, et al. Does Pizza Consumption Favor an Improved Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis? Nutrients. 2023; 15(15):3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153449

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Vito, Roberta, Maria Parpinel, Michela Carola Speciani, Federica Fiori, Rachele Bianco, Roberto Caporali, Francesca Ingegnoli, Isabella Scotti, Tommaso Schioppo, Tania Ubiali, and et al. 2023. "Does Pizza Consumption Favor an Improved Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis?" Nutrients 15, no. 15: 3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153449

APA StyleDe Vito, R., Parpinel, M., Speciani, M. C., Fiori, F., Bianco, R., Caporali, R., Ingegnoli, F., Scotti, I., Schioppo, T., Ubiali, T., Cutolo, M., Grosso, G., Ferraroni, M., & Edefonti, V. (2023). Does Pizza Consumption Favor an Improved Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis? Nutrients, 15(15), 3449. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15153449