Athlete Preferences for Nutrition Education: Development of and Findings from a Quantitative Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Development of Athlete Nutrition Education Preferences Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Pedagogy

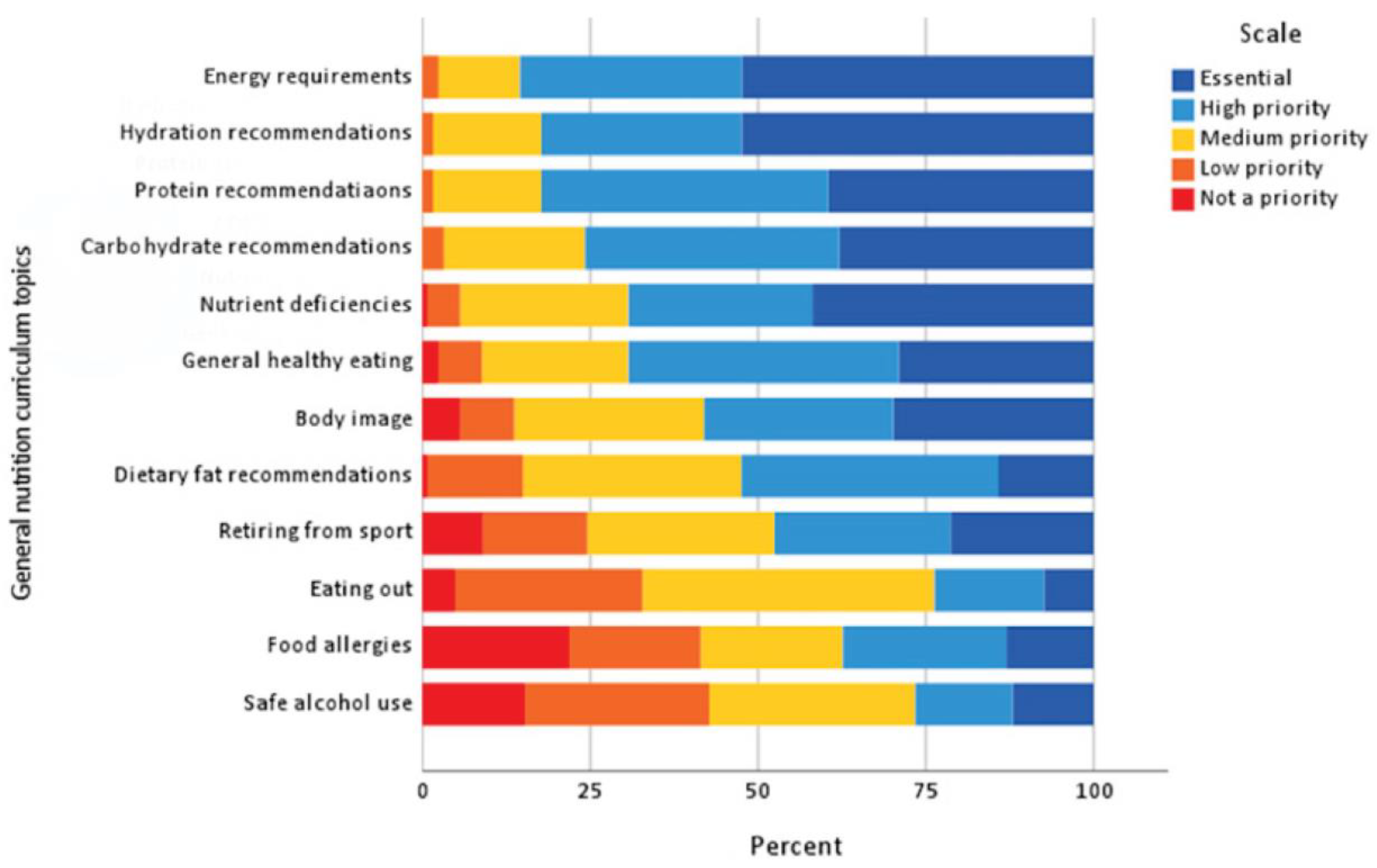

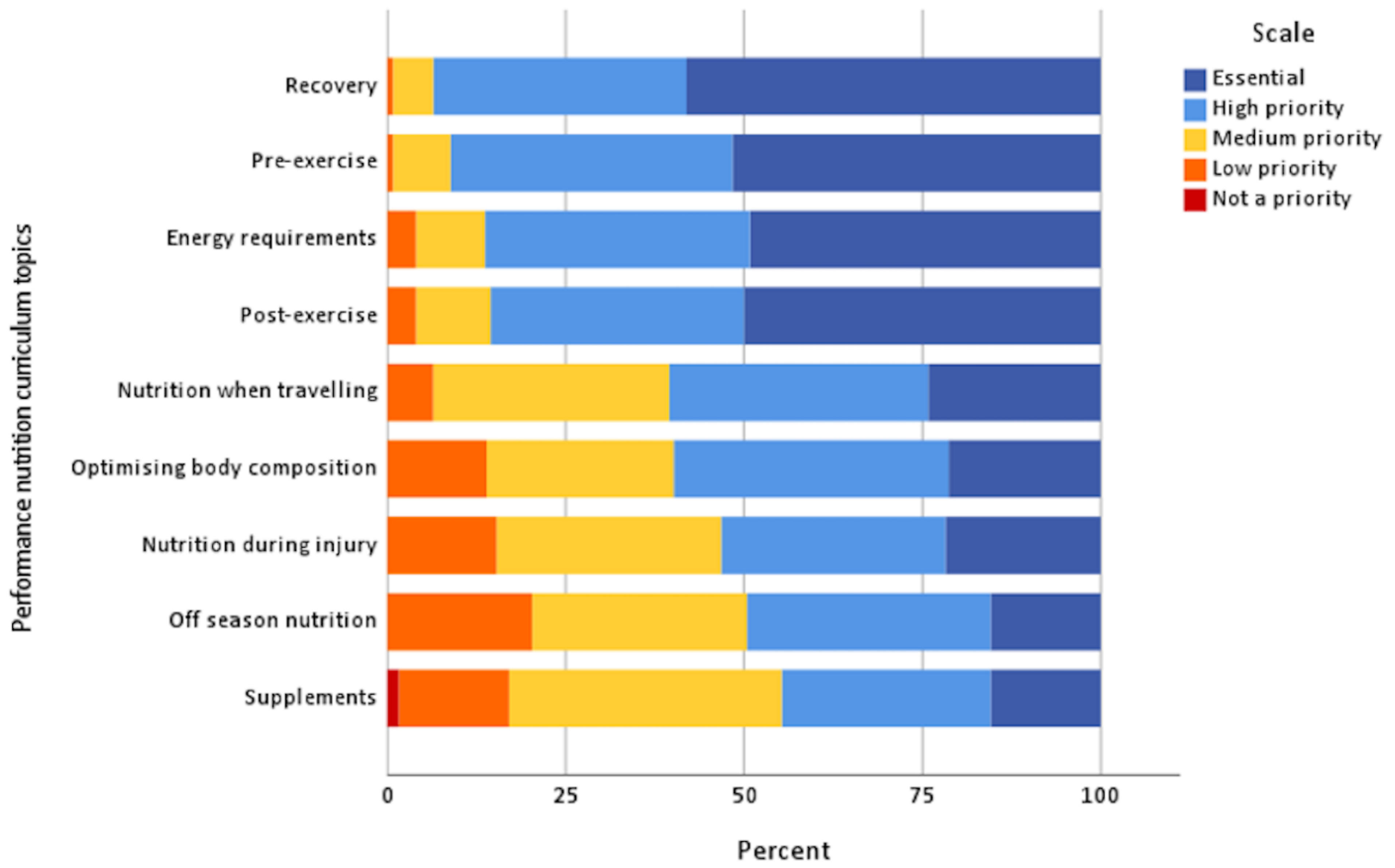

3.3. Content

3.4. Format

3.5. Facilitator

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Findings

4.2. Pedagogy Preferences

4.3. Content Preferences

4.4. Format and Facilitator Preferences

4.5. Implications of Findings

4.6. Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American College of Sports Medicine, Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada. Joint Position Statement: Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2016, 48, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Heaney, S.E.; Prvan, T.; O’Connor, H.T. Relationship between general nutrition knowledge and dietary quality in elite athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2015, 25, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhart, S.J.; Pelly, F.E. Dietary intake of athletes seeking nutrition advice at a major international competition. Nutrients 2016, 8, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; Jones, B.; Sutton, L.; King, R.F.G.J.; Duckworth, L.C. Dietary intakes of elite 14- to 19-year-old English academy rugby players during a pre-season training period. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2016, 26, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerenhouts, D.; Hebbelinck, M.; Poortmans, J.R.; Clarys, P. Nutritional habits of Flemish adolescent sprint athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2008, 18, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelly, F.E.; Thurecht, R.L.; Slater, G. Determinants of food choice in athletes: A systematic scoping review. Sport. Med.-Open 2022, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenhead, K.L.; Slater, G. A review of factors influencing athletes’ food choices. Sport. Med. 2015, 45, 1511–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurecht, R.; Pelly, F. Key factors influencing the food choices of athletes at two distinct major international competitions. Nutrients 2020, 12, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, S.; O’Connor, H.; Michael, S.; Gifford, J.; Naughton, G. Nutrition knowledge in athletes: A systematic review. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2011, 21, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, R.; Beck, K.L.; Manore, M.M.; Gifford, J.; Flood, V.M.; O’Connor, H. Effectiveness of education interventions designed to improve nutrition knowledge in athletes: A systematic review. Sport. Med. 2019, 49, 1769–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boidin, A.; Tam, R.; Mitchell, L.; Cox, G.R.; O’Connor, H. The effectiveness of nutrition education programmes on improving dietary intake in athletes: A systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 1359–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Díaz, S.; Yanci, J.; Castillo, D.; Scanlan, A.T.; Raya-González, J. Effects of nutrition education interventions in team sport players. A systematic review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, M.R.N.; Mitchell, N.; Sutton, L.; Backhouse, S.H. Sports nutritionists’ perspectives on enablers and barriers to nutritional adherence in high performance sport: A qualitative analysis informed by the COM-B model and theoretical domains framework. J. Sport. Sci. 2019, 37, 2075–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strawser, M. Training and development: Communication and the multigenerational workplace. J. Commun. Pedagog. 2021, 4, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risa, B. Creative communication strateges for multigenerational students. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2019, 17, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, B.E.P.; Baker, D.F.; Braakhuis, A.J. Social media as a nutrition resource for athletes: A cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, D.M.; Lefevre, C.; Cunniffe, B.; Tod, D.; Close, G.L.; Morton, J.P.; Murphy, R. Performance Nutrition in the digital era—An exploratory study into the use of social media by sports nutritionists. J. Sport. Sci. 2019, 37, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashton, L.M.; Morgan, P.J.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Collins, C.E. Young men’s preferences for design and delivery of physical activity and nutrition interventions: A mixed-methods study. Am. J. Men’s Health 2017, 11, 1588–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, A.; Porteous, H.E.; Palmer, M.A. Investigating antenatal nutrition education preferences in South-East Queensland, including Maori and Pasifika women. Women Birth 2018, 31, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, K.; Erdman, K.A.; Stadnyk, M.; Parnell, J.A. Dietary supplement usage, motivation, and education in young Canadian athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2014, 24, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, S.; Belski, R.; Devlin, B.; Coutts, A.; Kempton, T.; Forsyth, A. A qualitative investigation of factors influencing the dietary intakes of professional australian football players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, M. What Are Athletes’ Preferences Regarding Nutrition Education Programmes? Master’s Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, A.K.A.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining training and performance caliber: A participant classification framework. Int. J. Sport. Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, J.; Czaja, R.F.; Blair, E.A. Designing Surveys: A Guide to Decisions and Procedures, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Couper, M.P. Designing Effective Web Surveys; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J.L.; Fleming, N. The VARK Questionnaire—For Athletes: VARK Questionnaire Version 8.01. 2013. Available online: https://vark-learn.com/the-vark-questionnaire/the-vark-questionnaire-for-athletes/ (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Braakhuis, A.; Williams, T.; Fusco, E.; Hueglin, S.; Popple, A. A comparison between learning style preferences, gender, sport and achievement in elite team sport athletes. Sports 2015, 3, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroshus, E.; Baugh, C.M. Concussion education in U.S. collegiate sport: What is happening and what do athletes want? Health Educ. Behav. 2016, 43, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beakey, M.; Keenan, B.; Tiernan, S.; Collins, K. Is it time to give athletes a voice in the dissemination strategies of concussion-related information? Exploratory examination of 2444 adolescent athletes. Clin. J. Sport Med. Off. J. Can. Acad. Sport Med. 2020, 30, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.J.; Young, M.D.; Smith, J.J.; Lubans, D.R. Targeted health behavior interventions promoting physical activity: A conceptual model. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2016, 44, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I.B.; Adachi, J.D.; Beattie, K.A.; MacDermid, J.C. Development and validation of a new tool to measure the facilitators, barriers and preferences to exercise in people with osteoporosis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, R.B.; Helwig, D.; Dettmann, J.; Taggart, T.; Woodruff, B.; Horsfall, K.; Brooks, M.A. Developing a performance nutrition curriculum for collegiate athletes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthe, I.; Raastad, T.; Refsnes, P.; Sundgot-Borgen, J. Effect of nutritional intervention on body composition and performance in elite athletes. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 13, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Brown, K.; Ramsay, S.; Falk, J. Changes in student-athletes’ self-efficacy for making healthful food choices and food preparation following a cooking education intervention. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 1056–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippou, E.; Middleton, N.; Pistos, C.; Andreou, E.; Petrou, M. The impact of nutrition education on nutrition knowledge and adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in adolescent competitive swimmers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Elias, S.S.; Abu Saad, H.; Taib, M.N.M.; Jamil, Z. Effects of sports nutrition education intervention on sports nutrition knowledge, attitude and practice, and dietary intake of Malaysian team sports athletes. Malays. J. Nutr. 2018, 24, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Patton-Lopez, M.M.; Manore, M.M.; Branscum, A.; Meng, Y.; Wong, S.S. Changes in sport nutrition knowledge, attitudes/beliefs and behaviors following a two-year sport nutrition education and life-skills intervention among high school soccer players. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, M.R.N.; Patterson, L.B.; Mitchell, N.; Backhouse, S.H. Athlete perspectives on the enablers and barriers to nutritional adherence in high-performance sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 52, 101831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abood, D.A.; Black, D.R.; Birnbaum, R.D. Nutrition education intervention for college female athletes. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2004, 36, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurecht, R.L.; Pelly, F.E. The Athlete Food Choice Questionnaire (AFCQ): Validity and reliability in a sample of international high-performance athletes. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2021, 53, 1537–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capling, L.; Tam, R.; Beck, K.L.; Slater, G.J.; Flood, V.M.; O’Connor, H.T.; Gifford, J.A. Diet quality of elite Australian athletes evaluated using the Athlete Diet Index. Nutrients 2021, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, R.; Flood, V.M.; Beck, K.L.; O’Connor, H.T.; Gifford, J.A. Measuring the sports nutrition knowledge of elite Australian athletes using the Platform to Evaluate Athlete Knowledge of Sports Nutrition Questionnaire. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 78, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, E.; Leszczyńska, T.; Kopeć, A.; Hojka, D. Nutritional behavior of Polish canoeist’s athletes: The interest of nutritional education. Sci. Sport 2016, 31, e79–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Melin, A.K.; Garthe, I.; Hollekim-Strand, S.M.; Ivarsson, A.; Koehler, K.; Logue, D.; Lundström, P.; Madigan, S.; Wasserfurth, P.; et al. Effects of a 16 week digital intervention on sports nutrition knowledge and behavior in female endurance athletes with Risk of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). Nutrients 2023, 15, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C.; Turner, K.D. The effects of educational delivery methods on knowledge retention. J. Educ. Bus. 2017, 92, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, L.; Anderson, T.; Garrison, D.R.; Archer, W. Assessing social presence in asynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Int. J. E-Learn. Distance Educ. 2007, 14, 50–71. [Google Scholar]

- Murimi, M.W.; Kanyi, M.; Mupfudze, T.; Amin, M.R.; Mbogori, T.; Aldubayan, K. Factors influencing efficacy of nutrition education interventions: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, L. The implementation and evaluation of a nutrition education programme for university elite athletes. Prog. Nutr. 2013, 15, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shifflett, B.; Timm, C.; Kahanov, L. Understanding of athletes’ nutritional needs among athletes, coaches, and athletic trainers. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2002, 73, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinn, C.; Schofield, G.; Wall, C. Evaluation of sports nutrition knowledge of New Zealand premier club rugby coaches. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2006, 16, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-McGehee, T.M.; Pritchett, K.L.; Zippel, D.; Minton, D.M.; Cellamere, A.; Sibilia, M. Sports nutrition knowledge among collegiate athletes, coaches, athletic trainers, and strength and conditioning specialists. J. Athl. Train. 2012, 47, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, S.; O’Connor, H.; Naughton, G.; Gifford, J. Towards an understanding of the barriers to good nutrition for athletes. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Coach. 2008, 3, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather, A.K.; Thorpe, H.; Ogilvie, M.; Sims, S.T.; Beable, S.; Milsom, S.; Schofield, K.L.; Coleman, L.; Hamilton, B. Biological and socio-cultural factors have the potential to influence the health and performance of elite female athletes: A cross sectional survey of 219 elite female athletes in Aotearoa New Zealand. Front. Sport. Act. Living 2021, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.; Schiavon, L.M.; Bellotto, M.L. Knowledge, nutrition and coaching pedagogy: A perspective from female Brazilian Olympic gymnasts. Sport Educ. Soc. 2017, 22, 511–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. Australian team sports athletes prefer dietitians, the internet and nutritionists for sports nutrition information. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L.; McKean, M.; O’Connor, H.; Prvan, T.; Slater, G. Client experiences and confidence in nutrition advice delivered by registered exercise professionals. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2021, 24, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veni Nella, S.; Endah Anisa, R.; Rusma, S.; Sari, D.; Firman, P. Online learning drawbacks during the COVID-19 pandemic: A psychological perspective. EnJourMe (Engl. J. Medeka) Cult. Lang. Teach. Engl. 2020, 5, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Participants, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| Median (25th, 75th percentile) | 22.0 (18, 27) | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 68 (54.8) | |

| Male | 50 (40.3) | |

| Not answered | 6 (4.8) | |

| Highest education level a | ||

| School ≤ year 11 | 4 (3.2) | |

| School year 12 or 13 | 40 (32.3) | |

| Polytechnic or apprenticeship | 4 (3.2) | |

| University | 69 (55.6) | |

| Not answered | 7 (5.6) | |

| Current living situation | ||

| With family | 48 (38.7) | |

| With partner/spouse | 31 (25.0) | |

| With housemates | 29 (23.4) | |

| Alone | 6 (4.8) | |

| Boarding school/hostel | 4 (3.2) | |

| Not answered | 6 (4.8) | |

| Food purchasing responsibility | ||

| Self | 51 (41.1) | |

| Another household member | 29 (23.4) | |

| Shared responsibility | 34 (27.4) | |

| Food service organization b | 4 (3.2) | |

| Not answered | 6 (4.8) | |

| Food preparation/cooking responsibility | ||

| Self | 47 (37.9) | |

| Another household member | 14 (11.3) | |

| Shared responsibility | 54 (43.5) | |

| Food service organization | 3 (2.4) | |

| Not answered | 6 (4.8) | |

| Special dietary requirements c | ||

| Yes | 24 (19.4) | |

| No | 94 (75.8) | |

| Not answered | 6 (4.8) | |

| Sport d | ||

| Rowing | 33 (26.6) | |

| Athletics | 11 (8.9) | |

| Cycling | 11 (8.9) | |

| Triathlon | 9 (7.3) | |

| Kayaking/canoeing | 8 (6.5) | |

| Skating | 8 (6.5) | |

| Rugby | 7 (5.6) | |

| Auto racing | 6 (4.8) | |

| Swimming | 6 (4.8) | |

| Sailing | 4 (3.2) | |

| Hockey | 3 (2.4) | |

| Table tennis | 3 (2.4) | |

| Basketball | 2 (1.6) | |

| Para-equestrian | 2 (1.6) | |

| Other | 3 (2.4) | |

| Not answered | 6 (4.8) | |

| Highest level of participation | ||

| National | 44 (35.5) | |

| International—age group | 35 (28.2) | |

| International—open | 37 (29.8) | |

| Not answered | 8 (6.5) | |

| Years competing at Tier 3 or Tier 4 e | ||

| 1 to 3 | 41 (33.1) | |

| 3 to 5 | 37 (29.8) | |

| 5 to 10 | 24 (19.4) | |

| 10 plus | 14 (11.3) | |

| Not answered | 8 (6.5) | |

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Athletes of the same sporting calibre | 76 (61.3) |

| Athletes of similar age | 65 (52.4) |

| Teammates | 64 (51.6) |

| Coaches | 64 (51.6) |

| Any athlete interested in performance nutrition | 50 (40.3) |

| Athletes of the same gender | 41 (33.1) |

| Athletes competing in the same sport | 40 (32.3) |

| Any person interested in performance nutrition | 30 (24.2) |

| Personal support members (e.g., partner, family, parents) | 29 (23.4) |

| Other b | 1 (0.8) |

| Session Variable | In Person Group Session, n (%) | Online Session, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| People in session a | |||

| 1–5 | 39 (31.5) | 21 (16.9) | |

| 6–10 | 55 (44.4) | 39 (31.5) | |

| 11–20 | 26 (21.0) | 38 (30.6) | |

| 21–30 | 4 (3.2) | 13 (10.5) | |

| 31–40 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.4) | |

| 41–50 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| >50 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.6) | |

| Session duration | |||

| <15 min | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.6) | |

| 15–30 min | 20 (16.1) | 38 (30.6) | |

| 31–60 min | 79 (63.7) | 73 (58.9) | |

| 61–90 min | 22 (17.7) | 10 (8.1) | |

| 91 min–½ day | 2 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Full day | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Session frequency | |||

| <1 every 2 months | 15 (12.1) | 20 (16.1) | |

| 1 every 2 months | 39 (31.5) | 33 (26.6) | |

| 1 per month | 45 (36.3) | 48 (38.7) | |

| 2 per month | 19 (15.3) | 15 (12.1) | |

| 1 per week | 6 (4.8) | 8 (6.5) | |

| 2 per week | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total sessions a | |||

| 1–5 | 47 (37.9) | 44 (35.5) | |

| 6–10 | 47 (37.9) | 47 (37.9) | |

| 11–20 | 21 (16.9) | 24 (19.4) | |

| 21–30 | 5 (4.0) | 6 (4.8) | |

| 31–40 | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.8) | |

| 41–50 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | |

| >50 | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Personality traits | ||

| Credible | 91 (73.4) | |

| Relatable | 83 (66.9) | |

| Likeable | 83 (66.9) | |

| Non-judgmental | 82 (66.1) | |

| Organised | 79 (63.7) | |

| Friendly | 71 (57.3) | |

| Trustworthy | 71 (57.3) | |

| Motivated | 66 (53.2) | |

| Creative | 51 (41.1) | |

| Empathetic | 46 (37.1) | |

| Other b | 3 (2.4) | |

| Relatability | ||

| Knowledge of the sport | 106 (85.5) | |

| Willing to learn more about the sport | 88 (71.0) | |

| Prior experience as an athlete | 72 (58.1) | |

| Previous experience as an athlete in the sport | 27 (21.8) | |

| Athletic physical appearance | 16 (12.9) | |

| Same gender | 11 (8.9) | |

| Similar in age | 6 (4.8) | |

| Does not need to be relatable | 3 (2.4) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | |

| Credibility | ||

| Experience in sports nutrition | 95 (76.6) | |

| Registered nutrition professional | 84 (67.7) | |

| Experience in nutrition with athletes of similar calibre | 73 (58.9) | |

| Experience in nutrition with similar sports | 57 (46.0) | |

| Bachelor’s degree in nutrition | 56 (45.2) | |

| Experience in nutrition with the sport | 44 (35.5) | |

| Experience in general nutrition | 37 (29.8) | |

| Does not need to be credible | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Solly, H.; Badenhorst, C.E.; McCauley, M.; Slater, G.J.; Gifford, J.A.; Erueti, B.; Beck, K.L. Athlete Preferences for Nutrition Education: Development of and Findings from a Quantitative Survey. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112519

Solly H, Badenhorst CE, McCauley M, Slater GJ, Gifford JA, Erueti B, Beck KL. Athlete Preferences for Nutrition Education: Development of and Findings from a Quantitative Survey. Nutrients. 2023; 15(11):2519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112519

Chicago/Turabian StyleSolly, Hayley, Claire E. Badenhorst, Matson McCauley, Gary J. Slater, Janelle A. Gifford, Bevan Erueti, and Kathryn L. Beck. 2023. "Athlete Preferences for Nutrition Education: Development of and Findings from a Quantitative Survey" Nutrients 15, no. 11: 2519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112519

APA StyleSolly, H., Badenhorst, C. E., McCauley, M., Slater, G. J., Gifford, J. A., Erueti, B., & Beck, K. L. (2023). Athlete Preferences for Nutrition Education: Development of and Findings from a Quantitative Survey. Nutrients, 15(11), 2519. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15112519