Economic Evaluation of Individualized Nutritional Support for Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Heart Failure

Abstract

:1. Highlights

2. Introduction

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Health Economic Terms Used

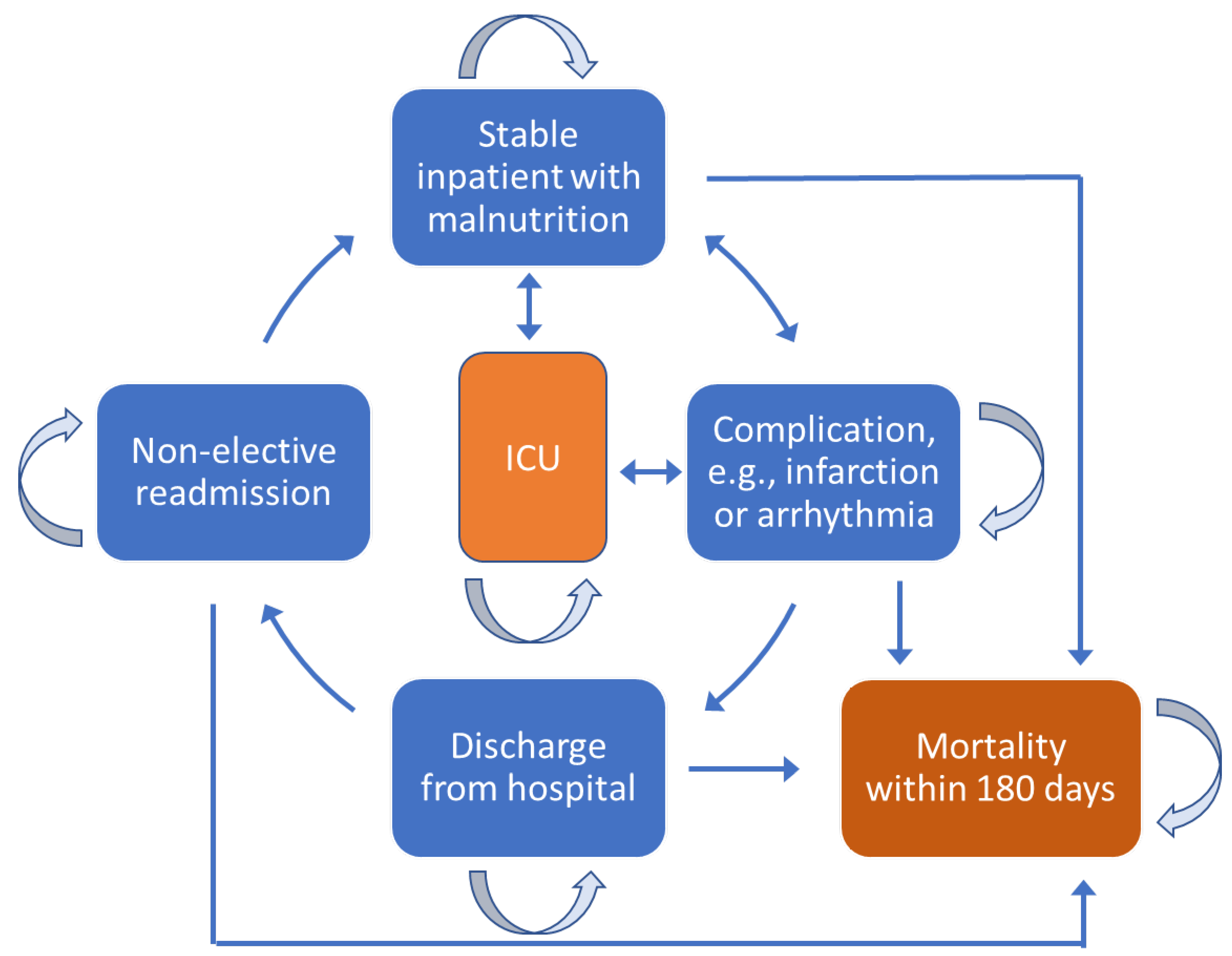

3.3. Description of Markov Simulation Model

3.4. Patient Population

3.5. Costs and Utilities

3.6. Base-Case and Cost-Effectiveness Analyses

3.7. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Results

4.1. Patient Outcomes

4.2. Base-Case Analyses of Cost-Effectiveness

4.3. Sensitivity Analyses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Clinical Perspective

6.2. Translational Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Trial registration

Appendix A

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Markov model | A Markov model is used to analyze systems that change on a random basis. Applied to healthcare, a Markov model assumes that a patient moves from one discrete health state to another, e.g., inpatient with malnutrition, inpatient with infectious complication, patient discharged from hospital, and patient readmitted to hospital non-electively. In modeling, the patient transitions from one state to another, with death as an irreversible state. |

| Base-case analysis | A base case analysis refers to the results obtained from running an economic model with the most likely or preferred set of assumptions and input values. |

| Cost-effectiveness | Cost-effectiveness analysis is a way to examine both the costs and health outcomes of an intervention. It compares an intervention with another intervention (or the status quo) by estimating how much it costs to gain a unit of a health outcome, such as a life-year gained or a death prevented. In healthcare, the goal is to maximize the benefit of treatment for a patient population while using resources efficiently, i.e., obtaining value for the cost. |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) | ICER is used to compare two different interventions in terms of the cost of gained effectiveness. ICER is computed by dividing the difference in cost of two interventions by the difference of their effectiveness, e.g., if treatment A costs 100 per patient and provides 1 quality-adjusted life day (QALD), and treatment B costs 1000 Swiss francs (SF) but provides 4 QALDs, the ICER of treatment B is 100–10 SF/4-1 = 30 SF per QALD. ICER is also called a cost-utility analysis. |

| Sensitivity analysis (SA) | SA is based on what happens to the dependent variable when other parameters change. It is considered a “what if” evaluation, which is used to determine the robustness of an assessment by examining the extent to which variables are affected by changes in assumptions or methods. |

| Transition Probability Per Day * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Phases | Individualized Nutritional Support | Distribution | SD | No Nutritional Support | Distribution | SD |

| Stable→stable | 0.00418 | Beta | 0.00258 | 0.00270 | Beta | 0.00206 |

| Stable→AE | 0.00106 | Beta | 0.00099 | 0.00174 | Beta | 0.00150 |

| Stable→ICU | 0.00018 | Beta | 0.00019 | 0.00017 | Beta | 0.00019 |

| Stable→Death | 0.00171 | Beta | 0.00148 | 0.00210 | Beta | 0.00173 |

| AE→Stable | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 |

| AE→AE | 0.00293 | Beta | 0.00222 | 0.00206 | Beta | 0.00174 |

| AE→ICU | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 | 0.00013 | Beta | 0.00016 |

| AE→Death | 0.00493 | Beta | 0.00278 | 0.00608 | Beta | 0.00285 |

| ICU→Stable | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 |

| ICU→AE | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | Beta | 0.00000 |

| ICU→ICU | 0.00508 | Beta | 0.00270 | 0.00608 | Beta | 0.00282 |

| ICU→Death | 0.00283 | Beta | 0.00209 | 0.00225 | Beta | 0.00184 |

| Stable→Release | 0.00171 | Beta | 0.00274 | 0.00210 | Beta | 0.00279 |

| Release→Stable | 0.00233 | Beta | 0.00187 | 0.00229 | Beta | 0.00185 |

| Release→Release | 0.00592 | Beta | 0.00280 | 0.00601 | Beta | 0.00280 |

| Parameters | Control Group (N = 324) | Intervention Group (N = 321) | p-Value | Regression Analysis (Adjusted) (95% CI and p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ||||

| All-cause mortality within 30 days | 48 (14.8%) | 27 (8.4%) | 0.013 | 0.44 (0.26 to 0.75) p = 0.002 |

| All-cause mortality within 180 days | 102 (31.5%) | 85 (26.5%) | 0.19 | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.996) p = 0.047 |

| MACE within 30 days | 87 (26.9%) | 56 (17.4%) | 0.005 | 0.50 (0.34 to 0.75) p = 0.001 |

| Admission to the intensive care unit within 30 days | 10 (3.1%) | 10 (3.1%) | 0.96 | 0.97 (0.39 to 2.40) p = 0.943 |

| Non-elective hospital readmission within 180 days | 84 (25.9%) | 92 (28.7%) | 0.38 | 1.23 (0.86 to 1.76) p = 0.245 |

| Non-elective hospital readmission within 30 days | 27 (8.3%) | 29 (9.0%) | 0.72 | 1.11 (0.64 to 1.94) p = 0.699 |

| Mean length of stay (days) | 9.8 (6.2) | 10.4 (7.1) | 0.24 | 0.53 (−0.46 to 1.57) p = 0.284 |

| 20% of Outpatients | 50% of Outpatients | 100% of Outpatients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Input for Outpatient Nutritional Support in Swiss Francs (SF) | |||

| 5 SF | 2131 SF | 2135 SF | 2142 SF |

| 100 SF | 3290 SF | 3376 SF | 3519 SF |

| 1000 SF | 14,269 SF | 15,131 SF | 16,566 SF |

| Maximum input to remain below SF 100,000/cost-effectiveness threshold | 8027 SF | 7497 SF | 6755 SF |

References

- Lippi, G.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Global epidemiology and future trends of heart failure. AME Med. J. 2020, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Muntner, P.; Alonso, A.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Das, S.R.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e56–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbich, M.; Globe, G.; Pantiri, K.; Heisen, M.; Bennison, C.; Wirtz, H.S.; Tanna, G.L.D. A systematic review of medical costs associated with heart failure in the USA (2014–2020). Pharmacoeconomics 2020, 38, 1219–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreae, C.; Stromberg, A.; Arestedt, K. Prevalence and associated factors for decreased appetite among patients with stable heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1703–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rogler, G.; Rosano, G. The heart and the gut. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, H.; Qian, H. Relationship between enteral nutrition and serum levels of inflammatory factors and cardiac function in elderly patients with heart failure. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure. Heart 2007, 93, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lena, A.; Coats, A.J.S.; Anker, M.S. Metabolic disorders in heart failure and cancer. ESC Heart Fail. 2018, 5, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Billingsley, H.E.; Hummel, S.L.; Carbone, S. The role of diet and nutrition in heart failure: A state-of-the-art narrative review. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 63, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Sattler, E.L.P. Nutrition as treatment modality in heart failure. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moick, S.; Simon, J.; Hiesmayr, M. Nutrition care quality indicators in hospitals and nursing homes: A systematic literature review and critical appraisal of current evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, A.; Loose, C.; Bell, J.; Partridge, J.; Nelson, J.; Goates, S. Health system quality improvement: Impact of prompt nutrition care on patient outcomes and health care costs. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2016, 31, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, A.; Partridge, J.; Jonnalagadda, S.S. Clinical and economic value of nutrition in healthcare: A nurse’s perspective. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2019, 34, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sriram, K.; Sulo, S.; VanDerBosch, G.; Partridge, J.; Feldstein, J.; Hegazi, R.A.; Summerfelt, W.T. A comprehensive nutrition-focused Quality Improvement Program reduces 30-day readmissions and length of stay in hospitalized patients. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2017, 41, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, K.; Sulo, S.; Dabbous, F.; Partridge, J.; Kozmic, S.; Landow, W.; VanDerBosch, G.; Falson, M.K.; Sriram, S. Reducing hospitalizations and costs: A home health nutrition-focused Quality Improvement Program. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tappenden, K.A.; Quatrara, B.; Parkhurst, M.L.; Malone, A.M.; Fanjiang, G.; Ziegler, T.R. Critical role of nutrition in improving quality of care: An interdisciplinary call to action to address adult hospital malnutrition. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.; Baumgartner, A.; Bounoure, L.; Bally, M.; Deutz, N.E.; Greenwald, J.L.; Stanga, Z.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P. Association of nutritional support with clinical outcomes among medical inpatients who are malnourished or at nutritional risk: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1915138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deutz, N.E.; Matheson, E.M.; Matarese, L.E.; Luo, M.; Baggs, G.E.; Nelson, J.L.; Hegazi, R.A.; Tappenden, K.A.; Ziegler, T.R.; NOURISH Study Group. Readmission and mortality in malnourished, older; hospitalized adults treated with a specialized oral nutritional supplement: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuetz, P.; Sulo, S.; Walzer, S.; Vollmer, L.; Brunton, C.; Kaegi-Braun, N.; Stanga, Z.; Mueller, B.; Gomes, F. Cost savings associated with nutritional support in medical inpatients: An economic model based on data from a systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e046402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulo, S.; Feldstein, J.; Partridge, J.; Schwander, B.; Sriram, K.; Summerfelt, W.T. Budget impact of a comprehensive nutrition-focused Quality Improvement Program for malnourished hospitalized patients. Am. Health Drug Benefits 2017, 10, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sulo, S.; Vargas, J.; Gomez, G.; Misas, J.D.; Serralde-Zuniga, A.E.; Correia, M. Hospital nutrition care informs potential cost-savings for healthcare: A budget impact analysis. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 42, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuetz, P.; Fehr, R.; Baechli, V.; Geiser, M.; Deiss, M.; Gomes, F.; Kutz, A.; Tribolet, P.; Bregenzer, T.; Braun, N.; et al. Individualised nutritional support in medical inpatients at nutritional risk: A randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2312–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersberger, L.; Dietz, A.; Burgler, H.; Bargetzi, A.; Bargetzi, L.; Kägi-Braun, N.; Tribolet, P.; Gomes, F.; Hoess, C.; Pavlicek, V.; et al. Individualized nutritional support for hospitalized patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 2307–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Fehr, R.; Baechli, V.; Geiser, M.; Gomes, F.; Kutz, A.; Tribolet, P.; Bregenzer, T.; Hoess, C.; Pavlicek, V.; et al. Design and rationale of the effect of early nutritional therapy on frailty, functional outcomes and recovery of malnourished medical inpatients trial (EFFORT): A pragmatic, multicenter, randomized-controlled trial. Int. J. Clin. Trials 2018, 5, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuetz, P.; Sulo, S.; Walzer, S.; Vollmer, Z.; Stanga, Z.; Gomes, F.; Rueda, R.; Mueller, B.; Partridge, J.; EFFORT trial collaborators. Economic evaluation of individualized nutritional support in medical inpatients: Secondary analysis of the EFFORT trial. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3361–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, A.; Sculpher, M. An introduction to Markov modelling for economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics 1998, 13, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, M.; Raffa, J. Markov models and cost effectiveness analysis: Applications in medical research. In MIT Critical Data, Editor Secondary Analysis of Electronic Health Records; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; Falk, V.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Harjola, V.-P.; Jankowska, E.A.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 891–975. [Google Scholar]

- ZRMB MARKETPLACE AG. Zur Rose Online-Apotheke [Online]. 2021. Available online: https://www.zurrose-shop.ch/de/lp/about-us? (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- SWISS DRG. SwissDRG-Version 10.0 SwissDRG-Version 10.0. Abrechnungsversion (2021/2021). Stand: 09.12.2020 [Online]. 2020. Available online: https://www.swissdrg.org/de/akutsomatik/swissdrg-system-1002021/fallpauschalenkatalog (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Bundesamt für Statistik (BFS). BFS Krankenhäuser 2019 [Online]. 2020. Available online: Extension://bfdogplmndidlpjfhoijckpakkdjkkil/pdf/viewer.html?file=https%3A%2F%2Fspitalstatistik.bagapps.ch%2Fdata%2Fdownload%2Fkzp19_publication.pdf%3Fv%3D1616491353 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Caro, J.J.; Briggs, A.H.; Siebert, U.; Kuntz, K.M.; ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force. Modeling good research practices—Overview: A report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force-1. Med. Decis. Mak. 2012, 32, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, R.; Fisman, D.; Zaric, G.S.; Postma, M.; Kretzschmar, M.; Edmunds, J.; Brisson, M.; ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force. Dynamic transmission modeling: A report of the ISPOR-SMDM Modeling Good Research Practices Task Force Working Group-5. Med. Decis. Mak. 2012, 32, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husereau, D.; Drummond, M.; Petrou, S.; Carswell, C.; Moher, D.; Greenberg, D.; Augustovski, F.; Briggs, A.H.; Mauskopf, J.; Loder, E.; et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2013, 14, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elia, M.; Normand, C.; Norman, K.; Laviano, A. A systematic review of the cost and cost effectiveness of using standard oral nutritional supplements in the hospital setting. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stratton, R.J.; Hebuterne, X.; Elia, M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of oral nutritional supplements on hospital readmissions. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 884–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulo, S.; Gramlich, L.; Benjamin, J.; McCauley, S.; Powers, J.; Sriram, K.; Mitchell, K. Nutrition interventions deliver value in healthcare: Real-world evidence. Nutr. Diet. Suppl. 2020, 12, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galekop, M.M.J.; Uyl-de Groot, C.A.; Ken Redekop, W. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies of interventions with a personalized nutrition component in adults. Value Health 2021, 24, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtold, M.L.; Regunath, H.; Tyler, R.; Guenter, P.; Barrocas, A.; Collins, N.A. Impact of a nutrition support therapy on hospital-acquired infections: A value analysis. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2021, 36, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, R.; Barrocas, A.; Guenter, P.; Torres, K.A.; Bechtold, M.L.; Chan, L.-N.; Collier, B.; Collins, N.A.; Evans, D.C.; Godamunne, K.; et al. Value of nutrition support therapy: Impact on clinical and economic outcomes in the United States. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Cohen, J.T.; Goates, S.; Luo, M.; Nelson, J.; Neumann, P.J. The cost-effectiveness of oral nutrition supplementation for malnourished older hospital patients. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2017, 15, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reisman, A.; Farrell, K.; Leitman, I. Value analysis of the costliest elective lifesaving procedures at an academic medical center. J. Sci. Innov. Med. 2018, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vest, A.R.; Chan, M.; Deswal, A.; Givertz, M.M.; Lekavich, C.; Lennie, T.; Litwin, S.E.; Parsly, L.; Rodgers, J.E.; Rich, M.W.; et al. Nutrition, obesity, and cachexia in patients with heart failure: A consensus statement from the Heart Failure Society of America Scientific Statements Committee. J. Card. Fail. 2019, 25, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cost Item | Cost Input, Swiss Francs (SF) | For Probabilistic Analysis | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution | SD, (SF) | |||

| Nutritional support inpatient | 5 | Gamma | 1 | ZRMB [30] |

| Nutritional support outpatient | 5 | Gamma | 1 | ZRMB [30] |

| Cost per day in normal ward | 1650 | Gamma | 1485 | BFS 2020 [32] |

| Cost per day in ICU | 4654 | Gamma | 3900 | DRG [31] |

| Average cost per complication (per day) | 1513 | Gamma | 1477 | DRG [31] |

| Life Days | Utilities | Cost (Swiss Francs, CHF) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Item | Individualized Nutritional Support | No Nutritional Support | Individualized Nutritional Support | No Nutritional Support | Individualized Nutritional Support | No Nutritional Support |

| Nutrition (support) | 679 | -- | ||||

| Days in normal ward | 123.84 | 111.24 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 204,342 | 183,544 |

| Days in ICU | 1.88 | 1.90 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8733 | 8857 |

| Complications | 10.09 | 14.20 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 15,263 | 21,477 |

| Post-hospital discharge life days | 18.77 | 21.47 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 19 | 0 |

| Total | 154.58 | 148.81 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 229,036 | 213,878 |

| Difference | 5.77 | 0.02 | 15,159 SF | |||

| Incremental Changes for Nutritional Support vs. No Nutritional Support | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Item | Cost, Swiss Francs (SF) | Life Days | ICER LD, SF |

| Day in normal ward | 20,798 | 12.60 | 1650 |

| Day in ICU | −123 | −0.03 | 4109 |

| Complication (AE) | −6214 | −4.11 | 1513 |

| Post-hospital stay, life days | 19 | −2.70 | −7 |

| Total | 15,159 | 5.77 | 2625 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schuetz, P.; Sulo, S.; Walzer, S.; Krenberger, S.; Stagna, Z.; Gomes, F.; Mueller, B.; Brunton, C. Economic Evaluation of Individualized Nutritional Support for Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091703

Schuetz P, Sulo S, Walzer S, Krenberger S, Stagna Z, Gomes F, Mueller B, Brunton C. Economic Evaluation of Individualized Nutritional Support for Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Nutrients. 2022; 14(9):1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091703

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchuetz, Philipp, Suela Sulo, Stefan Walzer, Sebastian Krenberger, Zeno Stagna, Filomena Gomes, Beat Mueller, and Cory Brunton. 2022. "Economic Evaluation of Individualized Nutritional Support for Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Heart Failure" Nutrients 14, no. 9: 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091703

APA StyleSchuetz, P., Sulo, S., Walzer, S., Krenberger, S., Stagna, Z., Gomes, F., Mueller, B., & Brunton, C. (2022). Economic Evaluation of Individualized Nutritional Support for Hospitalized Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Nutrients, 14(9), 1703. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091703