Mental and Behavioural Responses to Bahá’í Fasting: Looking behind the Scenes of a Religiously Motivated Intermittent Fast Using a Mixed Methods Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

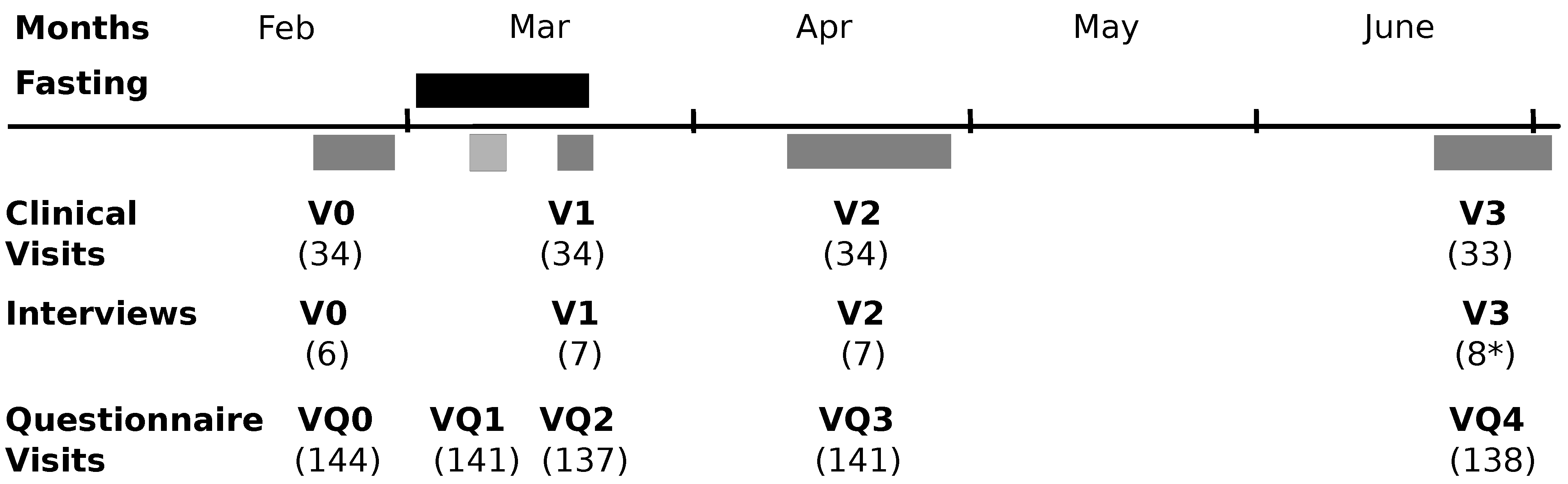

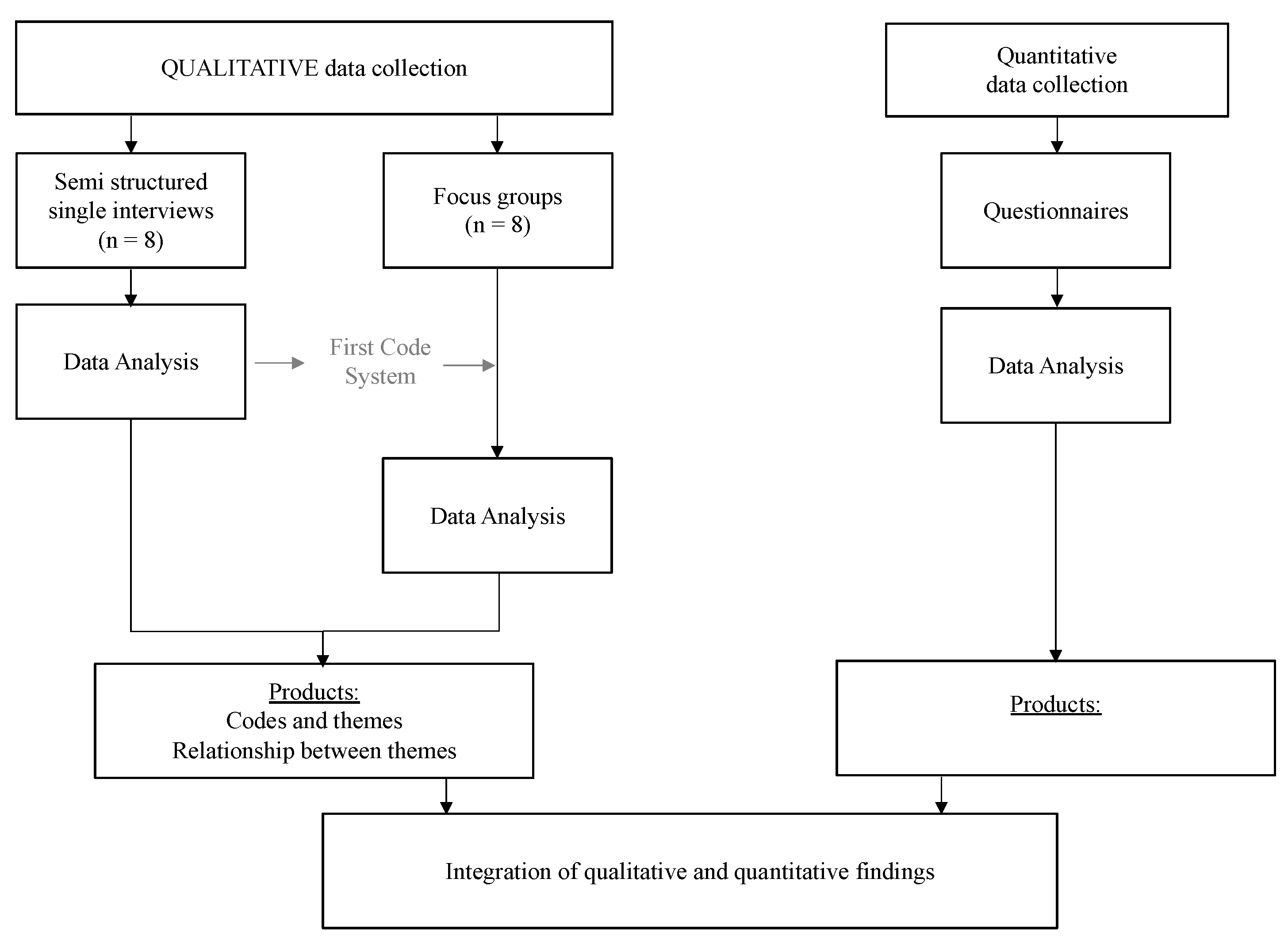

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Qualitative Design

2.4.1. Semi-Structured Individual Interviews

2.4.2. Focus Groups

2.5. Quantitative Design

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Qualitative Data Analysis

2.6.2. Quantitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Interview Findings

- (I).

- Individual interviews

- (A).

- Grounded in religion

“I think too little about my religion during the year and during these 19 days, I think about it more. (...) I read more of the texts and can tell that it does me good…Like a homecoming.”(P2, I2, section 80)

- (B).

- Elements of Fasting

- Motivation

- Changed daily structure

- Sense of community

- Opportunity to spend time alone

- (C).

- Impacts of Fasting

- -

- Experiencing physical consequences of behavioural changes during fasting

- -

- Improved well-being

- -

- Mindfulness

- -

- Discipline and freedom

- -

- Changes in daily habits

- (II).

- Focus groups

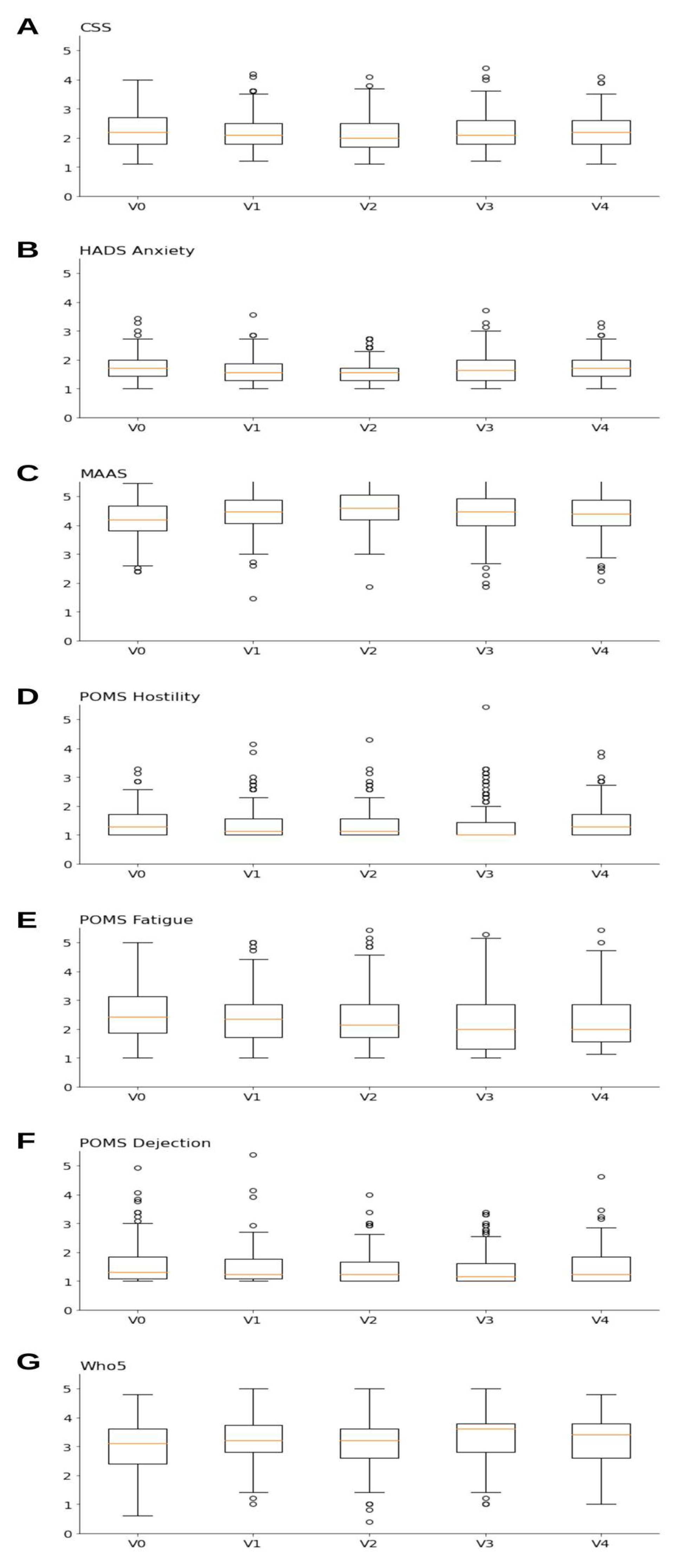

3.2. Quantitative Findings

3.3. Integration of Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions, Generalisability, and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BF | Bahá’í Fasting |

| IM | Department of Integrative Medicine at the Institute of Social Medicine, Epidemiology and Health Economics |

References

- Gabel, K.; Cienfuegos, S.; Kalam, F.; Ezpeleta, M.; Varady, K.A. Time-Restricted Eating to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Curr. Atheroscler Rep. 2021, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cienfuegos, S.; McStay, M.; Gabel, K.; Varady, K.A. Time restricted eating for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. J. Physiol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.M. Intermittent Fasting Induces Weight Loss, but the Effects on Cardiometabolic Health are Modulated by Energy Balance. Obesity 2019, 27, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gaeini, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Bahadoran, Z. Effects of Ramadan intermittent fasting on leptin and adiponectin: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hormones 2021, 20, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Bloomer, R.J. The impact of religious fasting on human health. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Persynaki, A.; Karras, S.; Pichard, C. Unraveling the metabolic health benefits of fasting related to religious beliefs: A narrative review. Nutrition 2017, 35, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebscher, D. Auswirkungen Religiösen Fastens auf Anthropometrische Parameter, Blutfettwerte und Hämodynamik Normalgewichtiger Gesunder Probanden [Effects of Religious Fasting on Anthropometric Parameters, Blood Lipid Levels and Hemodynamics of Normal Weight Healthy Subjects]. Available online: https://tud.qucosa.de/landing-page/https%3A%2F%2Ftud.qucosa.de%2Fapi%2Fqucosa%253A25118%2Fmets%2F/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Venegas-Borsellino, C.; Sonikpreet; Martindale, R.G. From Religion to Secularism: The Benefits of Fasting. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrzycki, A.; Cierpka-Kmiec, K.; Kmiec, Z.; Wronska, A. The role of low-calorie diets and intermittent fasting in the treatment of obesity and type-2 diabetes. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 69, 663–683. [Google Scholar]

- Templeman, I.; Gonzalez, J.T.; Thompson, D.; Betts, J.A. The role of intermittent fasting and meal timing in weight management and metabolic health. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2019, 79, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berthelot, E.; Etchecopar-Etchart, D.; Thellier, D.; Lancon, C.; Boyer, L.; Fond, G. Fasting Interventions for Stress, Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Wu, Q.; Saeed, M.; Sun, C. Gut microbiota-a positive contributor in the process of intermittent fasting-mediated obesity control. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- bahai.org. Divine Law. Available online: https://www.bahai.org/beliefs/life-spirit/character-conduct/divine-law/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- bahai.org. Institutional Capacity. Available online: https://www.bahai.org/action/institutional-capacity/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- WorldData.info. Available online: https://www.worlddata.info/religions/bahaism.php (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- bahai.org. A Global Community. Available online: https://www.bahai.org/national-communities/ (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- bahai.org. Science and Religion. Available online: https://www.bahai.org/beliefs/god-his-creation/ever-advancing-civilization/science-religion/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Yapici, A.; Bilican, F.I. Depression Severity and Hopelessness among Turkish University Students According to Various Aspects of Religiosity. Arch. Psychol. Relig. 2014, 36, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koushali, A.N.; Hajiamini, Z.; Ebadi, A.; Bayat, N.; Khamseh, F. Effect of Ramadan fasting on emotional reactions in nurses. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2013, 18, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- BaHammam, A.S.; Almeneessier, A.S. Recent Evidence on the Impact of Ramadan Diurnal Intermittent Fasting, Mealtime, and Circadian Rhythm on Cardiometabolic Risk: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, S.H.; Chowdhury, T.A.; Hussain, S.; Syed, A.; Karamat, A.; Helmy, A.; Waqar, S.; Ali, S.; Dabhad, A.; Seal, S.T.; et al. Ramadan and Diabetes: A Narrative Review and Practice Update. Diabetes Ther. 2020, 11, 2477–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.A.; Jahrami, H.; BaHammam, A.; Kalaji, Z.; Madkour, M.; Hassanein, M. A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of the impact of diurnal intermittent fasting during Ramadan on glucometabolic markers in healthy subjects. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 165, 108226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karras, S.N.; Koufakis, T.; Petroczi, A.; Folkerts, D.; Kypraiou, M.; Mulrooney, H.; Naughton, D.P.; Persynaki, A.; Zebekakis, P.; Skoutas, D.; et al. Christian Orthodox fasting in practice: A comparative evaluation between Greek Orthodox general population fasters and Athonian monks. Nutrition 2019, 59, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karras, S.N.; Persynaki, A.; Petroczi, A.; Barkans, E.; Mulrooney, H.; Kypraiou, M.; Tzotzas, T.; Tziomalos, K.; Kotsa, K.; Tsioudas, A.A.; et al. Health benefits and consequences of the Eastern Orthodox fasting in monks of Mount Athos: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Canale, R.E.; Marshall, K.E.; Kabir, M.M.; Bloomer, R.J. Impact of caloric and dietary restriction regimens on markers of health and longevity in humans and animals: A summary of available findings. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Counihan, C.M. An anthropological view of western women’s prodigious fasting: A review essay. Food Foodways 1989, 3, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeley-Harnik, G. Religion and Food: An Anthropological Perspective. J. Am. Acad. Relig. 1995, 63, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietler, M. Feasting and Fasting. In Oxford Handbook on the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; Available online: https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199232444.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199232444-e-14 (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Heiser, P. Fasten: Zur Popularität einer (religiösen) Praktik. Z. Für Relig. Ges. Und Polit. 2021, 5, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamney, J.B. Fasting and Modernization. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1980, 19, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, T. Historical continuities and discontinuities between religious and medical interpretations of extreme fasting. The background to Giovanni Brugnoli’s description of two cases of anorexia nervosa in 1875. Hist. Psychiatry 1992, 3, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppold-Liebscher, D.A.; Klatte, C.; Demmrich, S.; Schwarz, J.; Kandil, F.I.; Steckhan, N.; Ring, R.; Kessler, C.S.; Jeitler, M.; Koller, B.; et al. Effects of Daytime Dry Fasting on Hydration, Glucose Metabolism and Circadian Phase: A Prospective Exploratory Cohort Study in Baha’i Volunteers. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 662310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmrich, S.K.-L.; Koppold-Liebscher, D.; Klatte, C.; Steckhan, N.; Ring, R.M. Effects of religious intermittent dry fasting on religious experience and mindfulness: A longitudinal study among Baha’is. Am. Psychol. Assoc. Psychol. Relig. Spiritual. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mähler, A.; Jahn, C.; Klug, L.; Klatte, C.; Michalsen, A.; Koppold-Liebscher, D.; Boschmann, M. Metabolic Response to Daytime Dry Fasting in Bahá’í Volunteers. Accept. Publ. Nutr. 2021, 14, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2016, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tariq, S.; Woodman, J. Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Rep. 2013, 4, 2042533313479197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.P.; Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, J.M. Determining Sample Size. Qual. Health Res. 2000, 10, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. The Significance of Saturation. Qual. Health Res. 1995, 5, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinnbauer, B.J.; Pargament, K.I. Religiousness and Spirituality. In Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality; Paloutzian, R.F., Park, C.L., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, C.; Klein, C.; Swhajor-Biesemann, A.; Drexelius, U.; Keller, B.; Streib, H. Dimensions of “Spirituality”: The Semantics of Subjective Definitions. In Semantics and Psychology of Spirituality: A Cross-Cultural Analysis; Streib, H., Hood, J.R.W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 125–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A. The Grounded Theory Method. In Reviewing Qualitative Research in the Social Sciences; Trainor, A.A., Elizabeth, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.L. Grundlagen Qualitativer Sozialforschung. Datenanalyse und Theoriebildung in der Empirischen Soziologischen Forschung; Wilhelm Fink Verlag: Munich, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Witzel, A. Das problemzentrierte Interview. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2000, 1. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0001228 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Flick, U. Qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Einführung; Rowohlts Taschenbuchberlag: Reinbeck bei Hamburg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tausch, A.M.; Natalja, M. Fokusgruppen in der Gesundheitsforschung. GESIS Pap. 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joseph, S.; Linley, P.A.; Harwood, J.; Lewis, C.A.; McCollam, P. Rapid assessment of well-being: The Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS). Psychol. Psychother. 2004, 77, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Herrmann-Lingen, C.; Buss, U.; Snaith, R. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale—Deutsche Version (HADS-D) (3. Aktualisierte und neu Normierte Auflage); Hans Huber: Bern, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Michalak, J.; Heidenreich, T.; Ströhle, G.; Nachtigall, C. Die deutsche Version der Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale (MAAS) Psychometrische Befunde zu einem Achtsamkeitsfragebogen. Z. Für Klin. Psychol. Psychotherapie 2008, 37, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, C.; Blaser, G.; Geyer, M.; Schmutzer, G.; Brähler, E.; Bailer, H.; Grulke, N. The German short version of “Profile of Mood States” (POMS): Psychometric evaluation in a representative sample. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2005, 55, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allgaier, A.K.; Liwowsky, I.; Kramer, D.; Mergl, R.; Fejtkova, S.; Hegerl, U. Screening for depression in nursing homes: Validity of the WHO (Five) Well-Being Index. Neuropsychiatry 2011, 25, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierlein, C.; Kemper, C.J.; Kovaleva, A.; Rammstedt, B. Short scale for measuring general self-efficacy beliefs (ASKU). Methods Data Anal. 2013, 7, 251–278. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J.; Massion, A.O.; Kristeller, J.; Peterson, L.G.; Fletcher, K.E.; Pbert, L.; Lenderking, W.R.; Santorelli, S.F. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 1992, 149, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Langer, E.; Moldoveanu, M. The Construct of Mindfulness. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalsen, A. Wertvoller Verzicht: Fasten als Impul der Selbstheilung. In Heilen mit der Kraft der Natur, 2nd ed; Insel Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 88–237. [Google Scholar]

- Huether, G.S.; Rüther, E. Essen, Serotonin und Psyche: Die unbewußte nutritive Manipulation von Stimmungen und Gefühlen. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt 1998, 95, 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, R.; Reber, E.; Aeberhard, C.; Bally, L.; Schutz, P.; Stanga, Z. Fasting—Effects on the Human Body and Psyche. Praxis 2019, 108, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, C.M.; Almgren-Dore, I.; Dandeneau, S. “Letting Go” (Implicitly): Priming Mindfulness Mitigates the Effects of a Moderate Social Stressor. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foureur, M.; Besley, K.; Burton, G.; Yu, N.; Crisp, J. Enhancing the resilience of nurses and midwives: Pilot of a mindfulness-based program for increased health, sense of coherence and decreased depression, anxiety and stress. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 45, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenne Sarenmalm, E.; Martensson, L.B.; Andersson, B.A.; Karlsson, P.; Bergh, I. Mindfulness and its efficacy for psychological and biological responses in women with breast cancer. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 1108–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F. Spiritual well-being in the 21st century: It is time to review the current WHO’s health definition. J. Health Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, J.S. The World Health Organization’s definition of health: Social versus spiritual health. Soc. Indic. Res. 1996, 38, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, S.; Huppert, F.A.; Abbott, R.; Croudace, T.; Ploubidis, G.; Wadsworth, M.; Richards, M.; Kuh, D. A Life Course Approach to Well-Being. In Well-Being; Haworth, J., Hart, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fledderus, M.; Bohlmeijer, E.T.; Smit, F.; Westerhof, G.J. Mental health promotion as a new goal in public mental health care: A randomized controlled trial of an intervention enhancing psychological flexibility. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. Social relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, S.; Kumari, S. Religious Beliefs and Mental Health: An Empirical Review. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar]

- Faller, H.L.; Lang, H. Medizinische Psychologie und Soziologie, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Luszczynska, A.; Gutiérrez-Doña, B.; Schwarzer, R. General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. Int. J. Psychol. 2005, 40, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniaci, G.; La Cascia, C.; Giammanco, A.; Ferraro, L.; Chianetta, R.; Di Peri, R.; Sardella, Z.; Citarrella, R.; Mannella, Y.; Larcan, S.; et al. Efficacy of a fasting-mimicking diet in functional therapy for depression: A randomised controlled pilot trial. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 76, 1807–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.L.; Richard, S. Coping as a Mediator of Emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Taylor, C.B.; Williams, S.L.; Mefford, I.N.; Barchas, J.D. Catecholamin secretion as a function of perceived copinf self-efficacy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1985, 53, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonfeld, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Bieda, A.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. The effects of daily stress on positive and negative mental health: Mediation through self-efficacy. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, C.; Wu, R.; Wu, M.; Liu, W.; Dai, Z.; Li, Y. How Experiences Affect Psychological Responses During Supervised Fasting: A Preliminary Study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 651760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampling, D. Ascetic ideals and anorexia nervosa. J. Psychiatry Res. 1985, 19, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmi de Toledo, F.; Grundler, F.; Bergouignan, A.; Drinda, S.; Michalsen, A. Safety, health improvement and well-being during a 4 to 21-day fasting period in an observational study including 1422 subjects. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0209353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finnell, J.S.; Saul, B.C.; Goldhamer, A.C.; Myers, T.R. Is fasting safe? A chart review of adverse events during medically supervised, water-only fasting. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, S.K.; Conchin, S.; Bloomfield-Stone, S. A qualitative study into the impact of fasting within a large tertiary hospital in Australia--the patients’ perspective. J. Clin. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1946–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sipila, P.; Harrasova, G.; Mustelin, L.; Rose, R.J.; Kaprio, J.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. “Holy anorexia”-relevant or relic? Religiosity and anorexia nervosa among Finnish women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; O’Hara, L.; Tahboub-Schulte, S.; Grey, I.; Chowdhury, N. Holy anorexia: Eating disorders symptomatology and religiosity among Muslim women in the United Arab Emirates. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 260, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, K.A.; Terrell, D.J.; Sisemore, T.A.; Hecht, J.E. Religious coping style as a predictor of the severity of anorectic symptomology. Eat. Disord. 2014, 22, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 146 Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years (mean (SD)) | 45.19 (13.85) |

| Sex = male (%) | 65 (45.1) |

| Education (%) | |

| Still at school | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary/secondary school graduate | 4 (2.8) |

| Polytechnical secondary school graduate | 1 (0.7) |

| Higher qualification secondary school graduate (Realschule) | 4 (2.8) |

| High school graduate | 34 (23.6) |

| Technical college or University graduate | 95 (66.0) |

| Other | 6 (4.2) |

| Gross wage/year (%) | |

| <20,000 Euro | 60 (41.7) |

| 20,000–40,000 Euros | 30 (20.8) |

| 40,000–60,000 Euros | 19 (13.2) |

| 60,000–80,000 Euros | 14 (9.7) |

| >80,000 Euros | 21 (14.6) |

| Fasting experience in the past (%) | |

| Yes, once | 1 (0.7) |

| Yes, more than once | 142 (98.6) |

| None | 1 (0.7) |

| Kind of fasting experienced in the past (%) | |

| Prolonged therapeutic fasting | 2 (1.4) |

| Religious fasting | 138 (95.2) |

| Intermittent fasting | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 2 (1.4) |

| Not specified | 2 (1.4) |

| Duration of fasting experienced in the past (mean in days (SD)) | 18.64 (3.65) |

| Frequency of fasting in the past (%) | |

| Less than once a year | 9 (6.3) |

| 1–2 times per year | 128 (90.1) |

| 3–5 times per year | 2 (1.4) |

| 6–9 times per year | 1 (0.7) |

| More than 10 times per year | 2 (1.4) |

| Anticipated difficulties with fasting (%) | |

| Very easy | 12 (8.3) |

| Easy | 96 (66.7) |

| Difficult | 34 (23.6) |

| Very difficult | 2 (1.4) |

| Category | Code | Included in Code | Mentioned by Interviewee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust in God | Hand over responsibility to God | Feeling of the need to negotiate with God, only; justify actions towards God, find approvement in Gods’ word. | P7, P6, P5 |

| Submit to God | Submission to religious laws, importance of Gods’ word, obey to God, acceptance of limits due to religious laws. | P3, P6, P2 | |

| Trust in God’s word | Certainty that everything will be all right, trust in God and religious acts, trust in religious laws and their benefit for oneself, God like a parent who explains and shows the world to his believers. | P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7 | |

| To find security in religion | Religious places as source of trust and security. | P1 | |

| Meaning of religiosity in life of fasting persons | Religious laws | Importance of religious laws, importance of a sense of duty by existence of religious laws, religious laws as challenge and gift, as a chance to experience something new, to learn, religious laws build identity and close up to the group to the outside. | P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6, P7 |

| Fasting means to align oneself with God | Heart is aligned to God, to come closer to God by the act of fasting, fasting is a religious act, a blessing, fasting is done for God. | P3, P1, P7, P5, P2 | |

| Fasting is a central part of a religious life | Fasting is an element of religion, a fixed component, routine of Bahai life, fasting is spiritual. | P1, P7, P5 | |

| To be Bahai means to aim for progress | Process of progress, maturity process, self-development. | P1, P7, P4, P2 | |

| To do something good for the society | Support Gods’ project of development of the human being, change the society, being a critical mass, impulse for improvement of the world, to do good for society, positive influence on non-Bahaians. | P1, P7, P2 | |

| To eat mindfully | To take time for eating, to eat and drink with more awareness, to be aware of the act of eating. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| Category | Code | Included in Code | Mentioned by Interviewee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivation | Motivation | Earlier experiences that motivate to fast again, wish to return to God, to return to the core, wish to follow religious laws, wish to treat oneself by renunciation. | P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| Expectations | Description of concrete expectations from the fasting period. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P5 | |

| Changed daily structure | Structuring the day | Comparison of daily structure during fasting and daily life without fasting, descriptions of more or different structures, time efficiency, description of a fasting routine, flexibility of daily structure. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| Traditions | Traditions, taken over from parents and self-made traditions. | P1, P7, P6, P2 | |

| Intensify religious practices | Deepening of religious acts, spending more time with religious texts, meditation, and prayers. | P3, P1, P7, P6, P2, P5 | |

| Sense of community | Religious meetings are a source of well-being | Positive descriptions of religious get-togethers, community life during fasting, support by religious meetings. | P3, P1, P5 |

| Social support | Meaning of social support in general, support by family, friends, religious community, different importance of social groups. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| Influence of community life on lent | Benefits and disadvantages of community life during lent. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| Exchange with others influences the faster | Description of influences of conversations and interactions with people during lent. | P7, P4, P6, P5 | |

| Opportunity to spend time alone | To have time on my own | Descriptions of moments alone, values and importance of that time. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| To eat mindfully | To take time for eating, to eat and drink with more awareness, to be aware of the act of eating. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| Category | Code | Included in Code | Mentioned by Interviewee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiencing physical consequences of behavioural changes | To get to know myself better | Impact of actions and experiences on oneself. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5 |

| To experience what is good for my body | Concrete actions that impact the body. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| Improved well-being | To influence well-being | Descriptions of joy, peace, mental and inner strengthening, pleasure, less concerns, feeling better, more balanced, contentment. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5 |

| Doing good to myself | Descriptions of concrete acts, where interviewees want to do something good to themselves, fasting as anti-depressive, fasting as treat. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| To value fasting as positive | Positive descriptions of the value of fasting, gratitude for the ability to fast, fasting as inspiration. | P1, P7, P5, P2 | |

| Energy | Higher levels of energy during the fast. | P1, P7, P6 | |

| Lightness | Feeling of physical lightness, lightness as a new sense of vitality during fasting. | P1, P7, P4, P6 | |

| Cleanse | Feeling of physical and mental cleanse. | P3, P1 | |

| Mindfulness | Feeling of integration into the world | A feeling of order, classified as a feeling of being part of the world, recalibration. | P4, P7 |

| Mindfulness | Letting go, not reacting, distancing oneself, seeing clearly, reported mindfulness, meditative actions, special sensations (feeling grounded, feeling of lightness). | P1, P4, P6, P5 | |

| Higher awareness | Awareness, consciously doing something, feeling more conscious. | P3, P1, P4 | |

| Focus changes | Focus and concentration on myself, focus on the central in life. | P1, P7, P4, P6, P5 | |

| Being more sensitive and empathetic | Being more sensitive, empathetic, forgiving, friendly, loving, open to others. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5 | |

| Reflecting over myself and life | Reflections about life, small things, feelings, self-reflection. | P3, P1, P5 | |

| Overcoming the mundane | Body submits to mind, decisions free of physical needs, of constraints of nature, of the mundane, a state of dreaming while awake. | P3, P7, P5, P2 | |

| Connectedness | Connectedness with God, with others, with oneself, with nature. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5 | |

| Discipline and freedom | Freedom | Feeling free, gaining freedom. | P7, P4, P5 |

| Challenges | Challenges experienced during fasting. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| Discipline | Discipline. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| Development | Development. | P3, P1, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| Changes in individual behaviour | Assistive preparations for fasting | Description of concrete preparations for the fasting period, acts, and mental preparations. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| To create new habits | Descriptions of habits that are special during fasting and habits, which last after the fast. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 | |

| To eat mindfully | To take time for eating, to eat and drink with more awareness, to be aware of the act of eating. | P3, P1, P7, P4, P6, P5, P2 |

| Friedman Test | V0–V1 | V0–V2 | V0–V3 | V0–V4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | F | p | W | p | W | p | W | p | W | p |

| ASKU | 0.0091 | 0.2569 | 1976.5 | 0.6452 | 1479.0 | 0.0101 | 1767.5 | 0.1473 | 2157.0 | 0.4289 |

| CSS | 0.0305 | 0.0014 | 3227.5 | 0.0058 | 2482.5 | <0.0001 | 3812.0 | 0.066 | 4157.5 | 0.5039 |

| HADS Anxiety | 0.0873 | <0.0001 | 1456.5 | <0.0001 | 1096.5 | <0.0001 | 2451.5 | 0.003 | 2793.0 | 0.0537 |

| HADS Depression | 0.0104 | 0.195 | 2656.0 | 0.4687 | 1877.5 | 0.0055 | 3180.0 | 0.3745 | 2625.0 | 0.8626 |

| MAAS | 0.0951 | <0.0001 | 2862.5 | <0.0001 | 1927.0 | <0.0001 | 3065.0 | 0.0002 | 3297.0 | 0.0015 |

| POMS Hostility | 0.0288 | 0.0021 | 2287.0 | 0.1504 | 2293.0 | 0.087 | 2116.5 | 0.0232 | 3487.5 | 0.9517 |

| POMS Fatigue | 0.047 | <0.0001 | 3818.0 | 0.0278 | 3727.0 | 0.0432 | 2604.0 | <0.0001 | 3593.5 | 0.015 |

| POMS Dejection | 0.0415 | <0.0001 | 2378.0 | 0.0076 | 1964.5 | 0.0002 | 2236.5 | 0.0006 | 3440.0 | 0.4263 |

| POMS Vigour | 0.004 | 0.6783 | 4743.5 | 0.5903 | 4692.0 | 0.7167 | 4294.5 | 0.2873 | 4438.5 | 0.7401 |

| SDHS | 0.0098 | 0.2211 | 2774.0 | 0.1538 | 1855.5 | 0.003 | 2675.0 | 0.0473 | 3087.0 | 0.2549 |

| Who5 | 0.035 | 0.0004 | 3384.5 | 0.0081 | 3400.0 | 0.1099 | 2286.0 | <0.0001 | 3339.5 | 0.0328 |

| Questionnaire | Visit | M | SD | Med | Min | Q25% | Q75% | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASKU | VO | 4.02 | 0.67 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 4.33 | 5.00 |

| V1 | 4.03 | 0.72 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 3.67 | 4.67 | 5.00 | |

| V2 | 4.13 | 0.68 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 3.67 | 4.67 | 5.00 | |

| V3 | 4.08 | 0.66 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 4.33 | 5.00 | |

| V4 | 4.04 | 0.67 | 4.00 | 1.67 | 3.67 | 4.67 | 5.00 | |

| CSS | VO | 2.32 | 0.62 | 2.20 | 1.10 | 1.80 | 2.70 | 4.00 |

| V1 | 2.20 | 0.61 | 2.10 | 1.20 | 1.80 | 2.50 | 4.20 | |

| V2 | 2.14 | 0.63 | 2.00 | 1.10 | 1.70 | 2.50 | 4.10 | |

| V3 | 2.24 | 0.63 | 2.10 | 1.20 | 1.80 | 2.60 | 4.40 | |

| V4 | 2.27 | 0.63 | 2.20 | 1.10 | 1.80 | 2.60 | 4.10 | |

| HADS Anxiety | VO | 1.80 | 0.46 | 1.71 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 2.00 | 3.43 |

| V1 | 1.63 | 0.44 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 1.29 | 1.86 | 3.57 | |

| V2 | 1.59 | 0.40 | 1.57 | 1.00 | 1.29 | 1.71 | 2.71 | |

| V3 | 1.72 | 0.52 | 1.64 | 1.00 | 1.29 | 2.00 | 3.71 | |

| V4 | 1.74 | 0.47 | 1.71 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 2.00 | 3.29 | |

| HADS Depression | VO | 1.53 | 0.41 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 1.71 | 3.29 |

| V1 | 1.50 | 0.37 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 1.71 | 2.86 | |

| V2 | 1.47 | 0.37 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 1.71 | 2.57 | |

| V3 | 1.48 | 0.39 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 1.71 | 2.57 | |

| V4 | 1.51 | 0.39 | 1.43 | 1.00 | 1.14 | 1.71 | 3.00 | |

| MAAS | VO | 4.23 | 0.66 | 4.20 | 2.40 | 3.82 | 4.67 | 5.47 |

| V1 | 4.42 | 0.67 | 4.47 | 1.47 | 4.07 | 4.87 | 6.00 | |

| V2 | 4.57 | 0.68 | 4.60 | 1.87 | 4.20 | 5.05 | 5.93 | |

| V3 | 4.42 | 0.75 | 4.47 | 1.87 | 4.00 | 4.93 | 6.00 | |

| V4 | 4.39 | 0.73 | 4.40 | 2.07 | 4.00 | 4.87 | 6.00 | |

| POMS Hostility | VO | 1.45 | 0.52 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.71 | 3.29 |

| V1 | 1.39 | 0.56 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.57 | 4.14 | |

| V2 | 1.37 | 0.55 | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.57 | 4.29 | |

| V3 | 1.38 | 0.66 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 5.43 | |

| V4 | 1.45 | 0.59 | 1.29 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.71 | 3.86 | |

| POMS Fatigue | VO | 2.53 | 0.91 | 2.43 | 1.00 | 1.86 | 3.14 | 5.00 |

| V1 | 2.38 | 0.88 | 2.36 | 1.00 | 1.71 | 2.86 | 5.00 | |

| V2 | 2.36 | 0.92 | 2.14 | 1.00 | 1.71 | 2.86 | 5.43 | |

| V3 | 2.17 | 0.92 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.32 | 2.86 | 5.29 | |

| V4 | 2.32 | 0.96 | 2.00 | 1.14 | 1.57 | 2.86 | 5.43 | |

| POMS Dejection | VO | 1.59 | 0.73 | 1.31 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.85 | 4.92 |

| V1 | 1.48 | 0.66 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.08 | 1.77 | 5.38 | |

| V2 | 1.41 | 0.55 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.67 | 4.00 | |

| V3 | 1.42 | 0.57 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.62 | 3.38 | |

| V4 | 1.54 | 0.65 | 1.23 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.85 | 4.62 | |

| POMS Vigour | VO | 3.31 | 0.91 | 3.29 | 1.57 | 2.57 | 3.86 | 6.00 |

| V1 | 3.28 | 0.93 | 3.14 | 1.29 | 2.57 | 4.00 | 5.86 | |

| V2 | 3.35 | 0.98 | 3.14 | 1.57 | 2.71 | 4.00 | 6.00 | |

| V3 | 3.40 | 0.97 | 3.29 | 1.14 | 2.71 | 4.11 | 5.57 | |

| V4 | 3.35 | 0.98 | 3.29 | 1.00 | 2.57 | 4.00 | 5.57 | |

| SDHS | VO | 2.34 | 0.50 | 2.50 | 0.50 | 2.00 | 2.67 | 3.00 |

| V1 | 2.39 | 0.50 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 2.17 | 2.83 | 3.00 | |

| V2 | 2.44 | 0.48 | 2.50 | 0.50 | 2.17 | 2.83 | 3.00 | |

| V3 | 2.43 | 0.47 | 2.50 | 1.00 | 2.04 | 2.83 | 3.00 | |

| V4 | 2.40 | 0.53 | 2.50 | 0.67 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 3.00 | |

| Who5 | VO | 2.98 | 0.84 | 3.10 | 0.60 | 2.40 | 3.60 | 4.80 |

| V1 | 3.20 | 0.76 | 3.20 | 1.00 | 2.80 | 3.75 | 5.00 | |

| V2 | 3.09 | 0.85 | 3.20 | 0.40 | 2.60 | 3.60 | 5.00 | |

| V3 | 3.29 | 0.81 | 3.60 | 1.00 | 2.80 | 3.80 | 5.00 | |

| V4 | 3.18 | 0.83 | 3.40 | 1.00 | 2.60 | 3.80 | 4.80 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ring, R.M.; Eisenmann, C.; Kandil, F.I.; Steckhan, N.; Demmrich, S.; Klatte, C.; Kessler, C.S.; Jeitler, M.; Boschmann, M.; Michalsen, A.; et al. Mental and Behavioural Responses to Bahá’í Fasting: Looking behind the Scenes of a Religiously Motivated Intermittent Fast Using a Mixed Methods Approach. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051038

Ring RM, Eisenmann C, Kandil FI, Steckhan N, Demmrich S, Klatte C, Kessler CS, Jeitler M, Boschmann M, Michalsen A, et al. Mental and Behavioural Responses to Bahá’í Fasting: Looking behind the Scenes of a Religiously Motivated Intermittent Fast Using a Mixed Methods Approach. Nutrients. 2022; 14(5):1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051038

Chicago/Turabian StyleRing, Raphaela M., Clemens Eisenmann, Farid I. Kandil, Nico Steckhan, Sarah Demmrich, Caroline Klatte, Christian S. Kessler, Michael Jeitler, Michael Boschmann, Andreas Michalsen, and et al. 2022. "Mental and Behavioural Responses to Bahá’í Fasting: Looking behind the Scenes of a Religiously Motivated Intermittent Fast Using a Mixed Methods Approach" Nutrients 14, no. 5: 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051038

APA StyleRing, R. M., Eisenmann, C., Kandil, F. I., Steckhan, N., Demmrich, S., Klatte, C., Kessler, C. S., Jeitler, M., Boschmann, M., Michalsen, A., Blakeslee, S. B., Stöckigt, B., Stritter, W., & Koppold-Liebscher, D. A. (2022). Mental and Behavioural Responses to Bahá’í Fasting: Looking behind the Scenes of a Religiously Motivated Intermittent Fast Using a Mixed Methods Approach. Nutrients, 14(5), 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14051038