Pharmacokinetic Outcomes of the Interactions of Antiretroviral Agents with Food and Supplements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Highlights

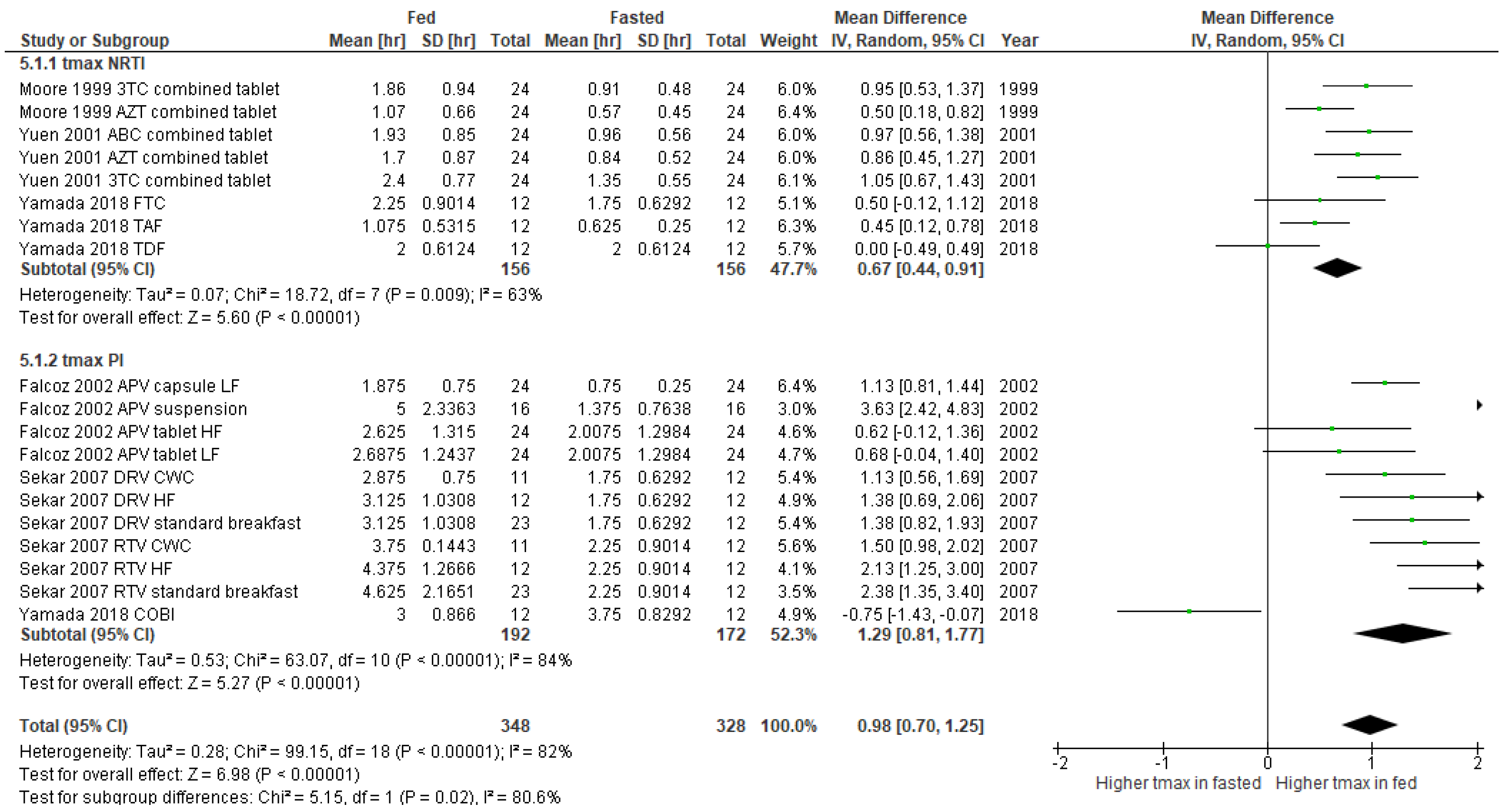

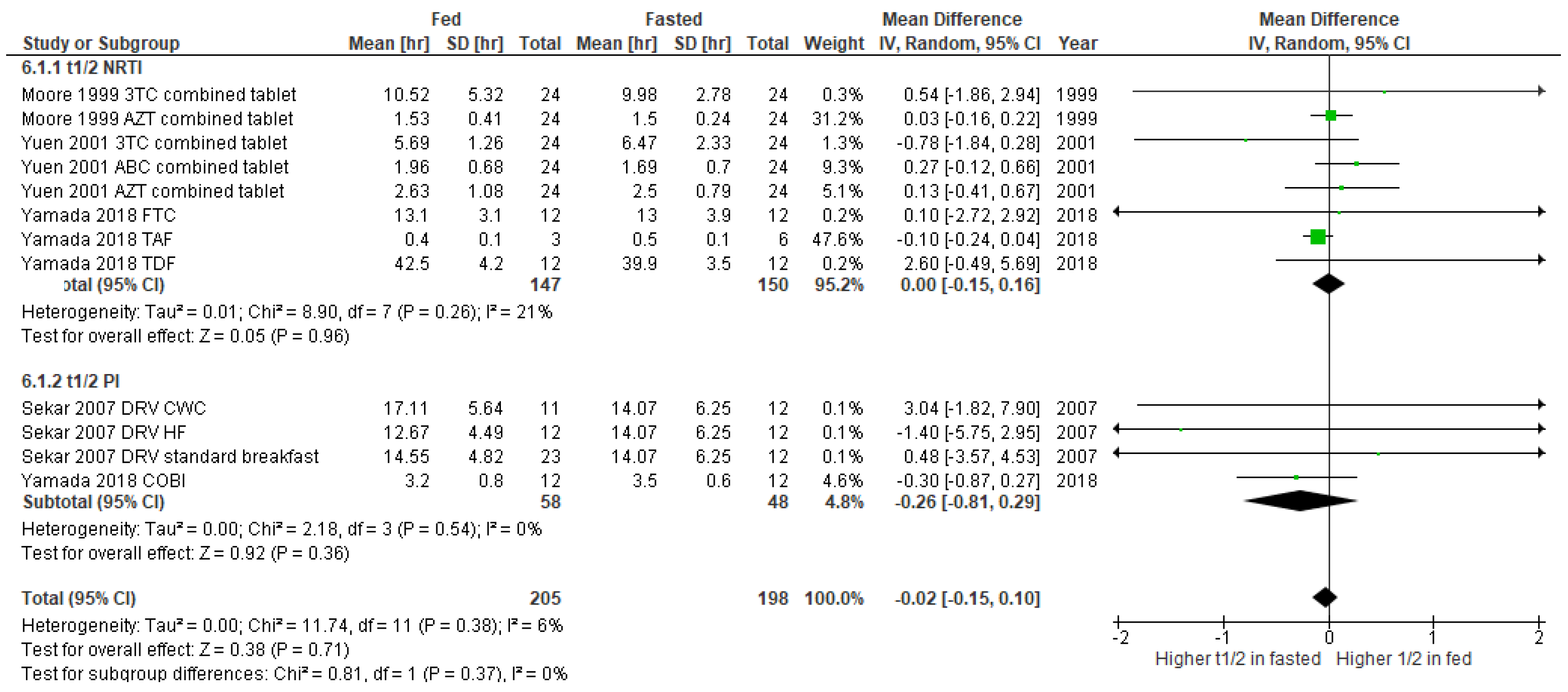

- High-fat meals delay the absorption (tmax) of ARVs like abacavir and lamivudine but increase the plasma concentrations of protease inhibitors (PIs) such as darunavir and ritonavir;

- Supplements like calcium and vitamin C can reduce ARV effectiveness, while others, such as quercetin and Ginkgo biloba, show no significant effects.

- Meal timing and content can influence ARV absorption; for instance, PIs benefit from food, while others may experience delays.

- Patients should be informed about the ways in which supplements can affect ARVs, and regular monitoring is key to preventing treatment failure.

Abstract

1. Introduction

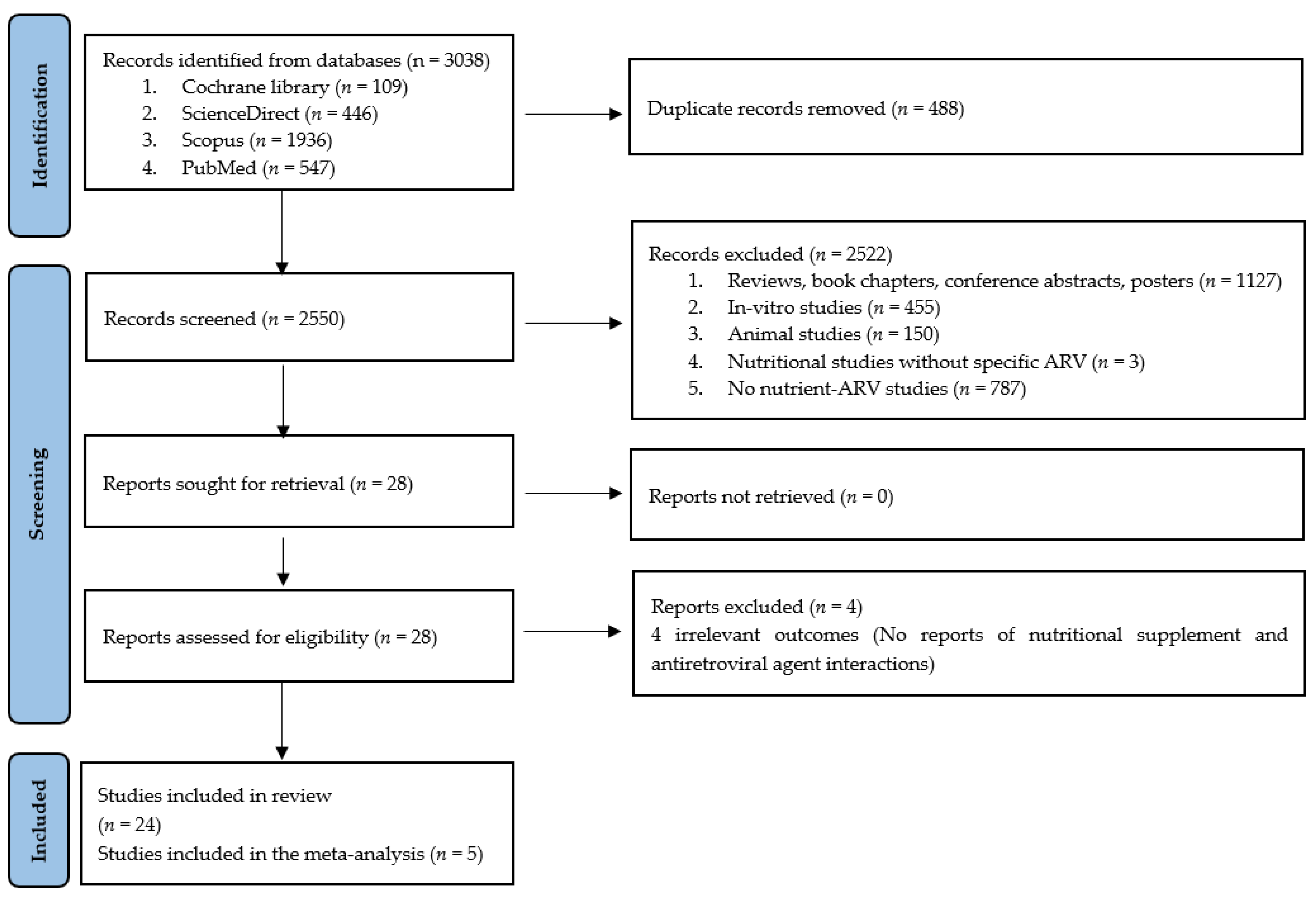

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Studies Included in the Qualitative Analysis

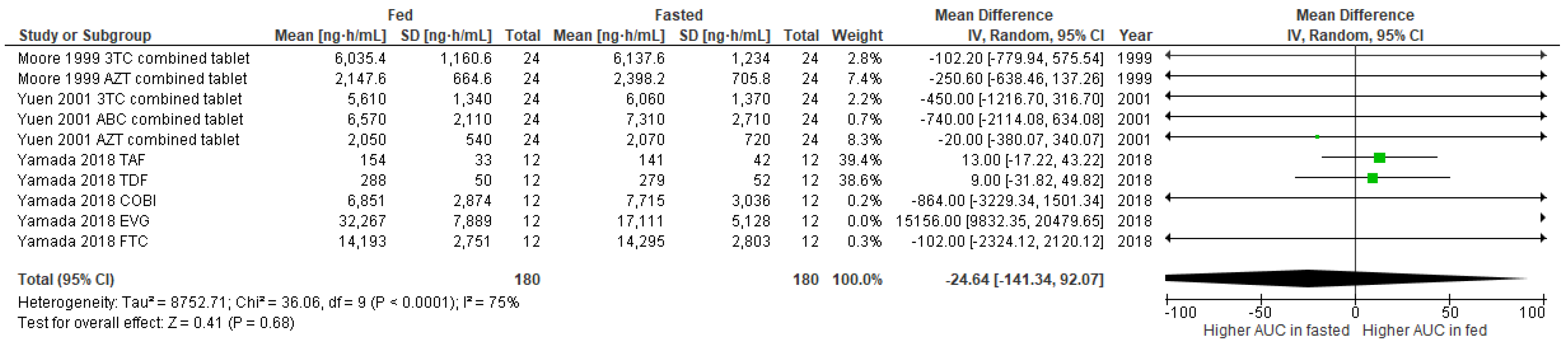

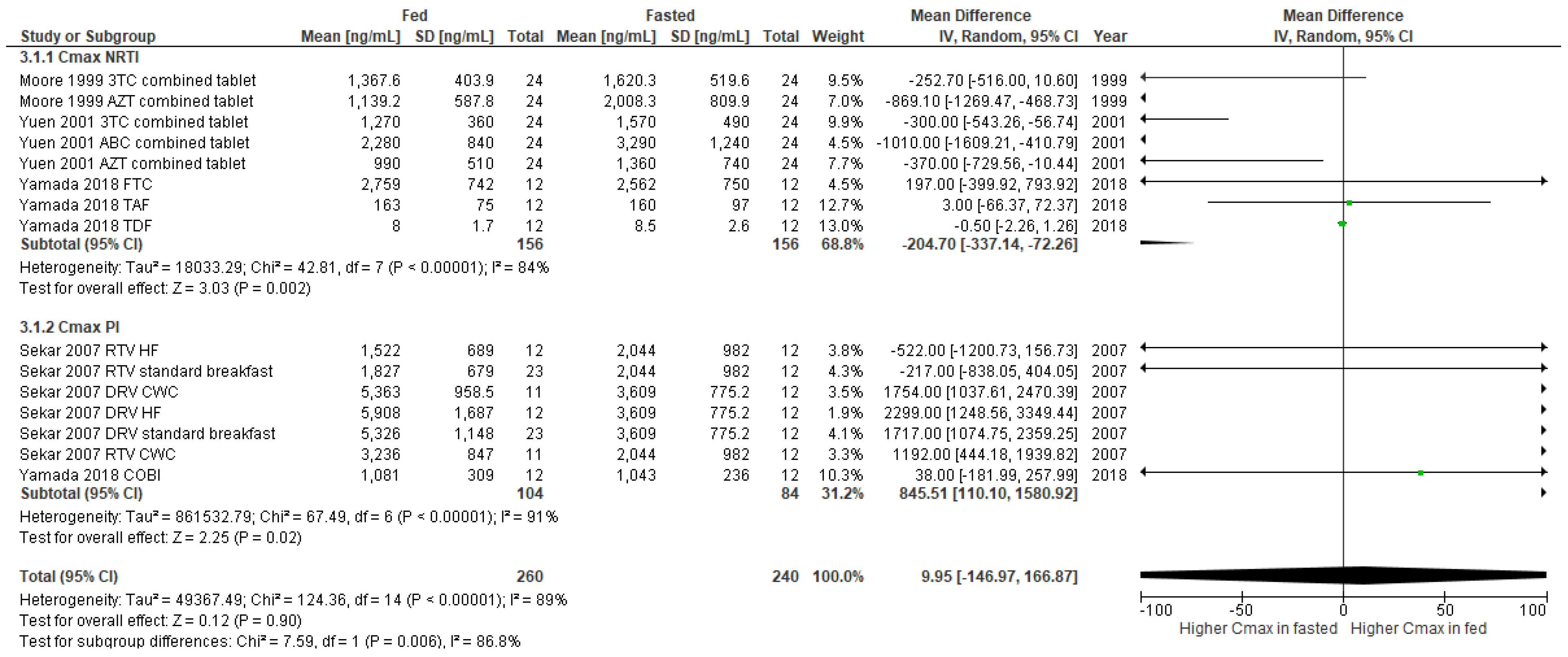

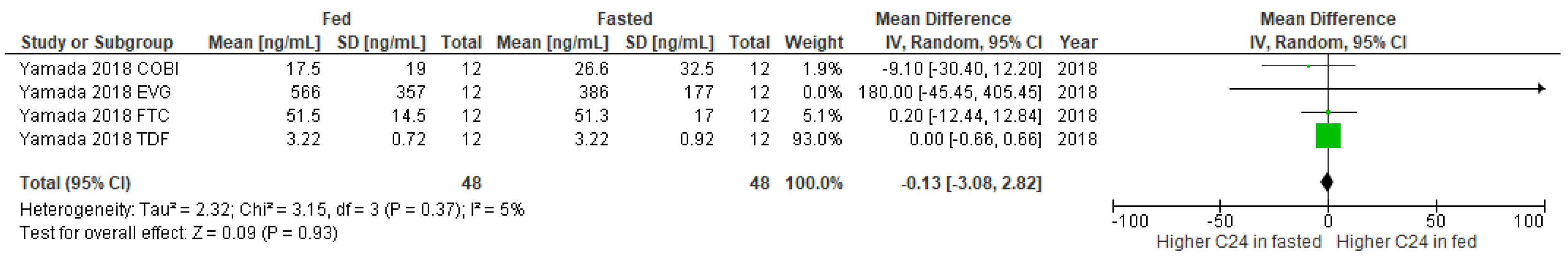

3.2. Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

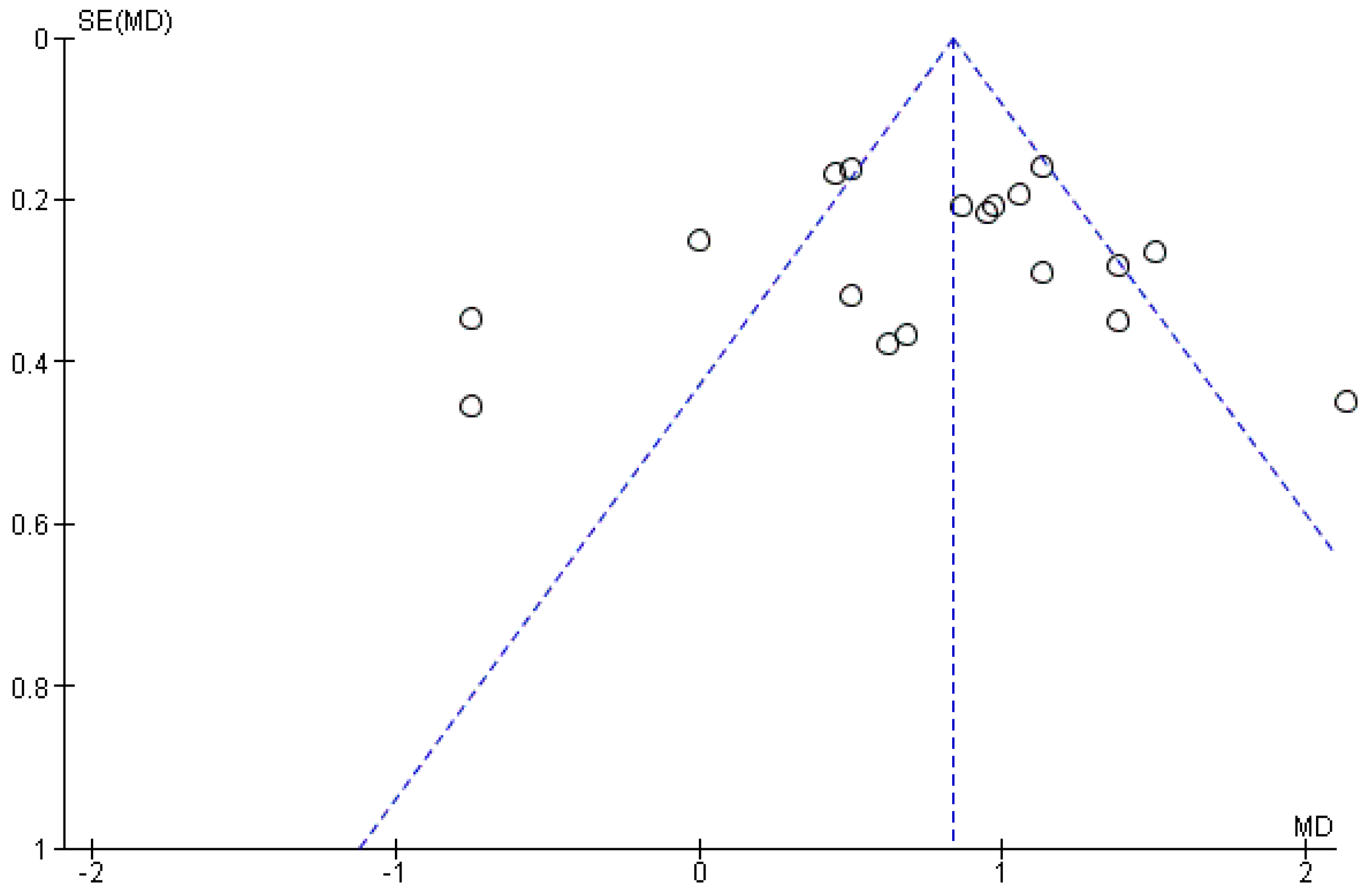

3.3. Publication Bias

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. International Statistics. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- HIV.gov. Global Statistics. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/global-statistics (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Prevention, Testing, Treatment, Service Delivery and Monitoring: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- European Food Safety Authority. Food Supplements. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/food-supplements (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Castleman, T.; Seumo-Fosso, E.; Cogill, B. Food and Nutrition Implications of Antiretroviral Therapy in Resource Limited Settings; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tonui, K.K.; Njogu, E.; Onyango, A.C. Dietary intake of HIV-seropositive clients attending Longisa County Hospital Comprehensive Care Clinic, Bomet County, Kenya. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 33, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, N.; Austin, J. A Clinical Review of Micronutrients in HIV Infection. J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care 2002, 1, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koethe, J.R.; Chi, B.H.; Megazzini, K.M.; Heimburger, D.C.; Stringer, J.S.A. Macronutrient supplementation for malnourished HIV-infected adults: A review of the evidence in resource-adequate and resource-constrained settings. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lorenc, A.; Robinson, N. A review of the use of complementary and alternative medicine and HIV: Issues for patient care. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2013, 27, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, L.E.; Dalhoff, K. Food-drug interactions. Drugs 2002, 62, 1481–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteves, F.; Rueff, J.; Kranendonk, M. The central role of cytochrome P450 in xenobiotic metabolism—A brief review on a fascinating enzyme family. J. Xenobiotics 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, P.L.; Fleisher, D.; Zhou, S.Y.; Kaul, D.; Kazanjian, P.; Li, C. Meal Composition effects on the oral bioavailability of indinavir in HIV-infected patients. Pharm. Res. 1999, 16, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Z.; Fan, C.H.; Kwan, H.S.; Wong, C.H.; Shek, K.Y.; Zuo, Z.; Lam, T.N. A review of food–drug interactions on oral drug absorption. Drugs 2017, 77, 1833–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.H.P.; Shaw, S.; Laurent, A.L.; Lloyd, P.; Duncan, B.; Morris, D.M.; O’Mara, M.J.; Pakes, G.E. Lamivudine/zidovudine as a combined formulation tablet: Bioequivalence compared with lamivudine and zidovudine administered concurrently and the effect of food on absorption. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1999, 39, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.L.; Kiser, J.J.; Hindman, J.T.; Meditz, A.L. Virologic failure with a raltegravir-containing antiretroviral regimen and concomitant calcium administration. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2011, 31, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koziolek, M.; Alcaro, S.; Augustijns, P.; Basit, A.W.; Grimm, M.; Hens, B.; Hoad, C.L.; Jedamzik, P.; Madla, C.M.; Maliepaard, M.; et al. The mechanisms of pharmacokinetic food-drug interactions–A perspective from the UNGAP group. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 134, 31–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.-L.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Yang, Z.-H.; Huang, D.; Weng, H.; Zeng, X.-T. Methodological quality (risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, R.; Álvarez-Pasquin, M.J.; Díaz, C.; del Barrio, J.L.; Estrada, J.M.; Gil, Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Sultan, S.; Haffar, S.; Bazerbachi, F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018, 23, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Hu, G.L.; Zheng, X.Y.; Chen, Q.; Threapleton, D.E.; Zhou, Z.H. The method quality of cross-over studies involved in Cochrane Systematic Reviews. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferschmidt, H.H.T.; Fattinger, K.E.; Ha, H.R.; Follath, F.; Krähenbühl, S. Grapefruit juice enhances the bioavailability of the HIV protease inhibitor saquinavir in man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1998, 45, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, G.J.; Lou, Y.; Thompson, N.F.; Otto, V.R.; Allsup, T.L.; Mahony, W.B.; Hutman, H.W. Abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine as a combined formulation tablet: Bioequivalence compared with each component administered concurrently and the effect of food on absorption. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 41, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzak, S.R.; Acosta, E.P.; Turner, M.; Edwards, D.J.; Hon, Y.Y.; Desai, H.D.; Jann, M.W. Effect of Seville orange juice and grapefruit juice on indinavir pharmacokinetics. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcoz, C.; Jenkins, J.M.; Bye, C.; Hardman, T.C.; Kenney, K.B.; Studenberg, S.; Fuder, H.; Prince, W.T. Pharmacokinetics of GW433908, a prodrug of amprenavir, in healthy male volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piscitelli, S.C.; Burstein, A.H.; Welden, N.; Gallicano, K.D.; Falloon, J. The effect of garlic supplements on the pharmacokinetics of saquinavir. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slain, D.; Amsden, J.R.; Khakoo, R.A.; Fisher, M.A.; Lalka, D.; Hobbs, G.R. Effect of high-dose vitamin C on the steady-state pharmacokinetics of the protease inhibitor indinavir in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy 2005, 25, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouly, S.J.; Matheny, C.; Paine, M.F.; Smith, G.; Lamba, J.; Lamba, V.; Pusek, S.N.; Schuetz, E.G.; Stewart, P.W.; Watkins, P.B. Variation in oral clearance of saquinavir is predicted by CYP3A5*1 genotype but not by enterocyte content of cytochrome P450 3A5. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 78, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCenzo, R.; Frerichs, V.; Larppanichpoonphol, P.; Predko, L.; Chen, A.; Reichman, R.; Morris, M. Effect of quercetin on the plasma and intracellular concentrations of saquinavir in healthy adults. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2006, 26, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.; Kestens, D.; Spinosa-Guzman, S.; de Pauw, M.; de Paepe, E.; Vangeneugden, T.; Lefebvre, E.; Hoetelmans, R.M.W. The effect of different meal types on the pharmacokinetics of darunavir (TMC114)/ritonavir in HIV-negative healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 47, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.M.; Davey, R.T.; Voell, J.; Formentini, E.; Alfaro, R.M.; Penzak, S.R. Effect of Ginkgo biloba extract on lopinavir, midazolam and fexofenadine pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2008, 24, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Song, I.; Borland, J.; Patel, A.; Lou, Y.; Chen, S.; Wajima, T.; Peppercorn, A.; Min, S.S.; Piscitelli, S.C. Pharmacokinetics of the HIV integrase inhibitor S/GSK1349572 co-administered with acid-reducing agents and multivitamins in healthy volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, M.M.; Chairez, C.L.; Gordon, L.A.; Alfaro, R.M.; Kovacs, J.A.; Penzak, S.R. Influence of Panax ginseng on the steady state pharmacokinetic profile of lopinavir-ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2014, 34, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Borland, J.; Arya, N.; Wynne, B.; Piscitelli, S. Pharmacokinetics of dolutegravir when administered with mineral supplements in healthy adult subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 55, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, A.M.; Holton, M.; Conn, I.; Davies, M.; Choukour, M.; Wynne, B.R. Relative bioavailability of a dolutegravir dispersible tablet and the effects of low- and high-mineral-content water on the tablet in healthy adults. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2017, 6, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, H.; Ikushima, I.; Nemoto, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Ninomiya, N.; Irie, S. Effects of a nutritional protein-rich drink on the pharmacokinetics of elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine, tenofovir alafenamide, and tenofovir compared with a standard meal in healthy Japanese male subjects. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2017, 7, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonemura, T.; Okada, N.; Sagane, K.; Okamiya, K.; Ozaki, H.; Iida, T.; Yamada, H.; Yagura, H. Effects of milk or apple juice ingestion on the pharmacokinetics of elvitegravir and cobicistat in healthy Japanese male volunteers: A randomized, single-dose, three-way crossover study. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2018, 7, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Fangel, S.; Justesen, U.S.; Black, F.T.; Pedersen, C.; Obel, N. The use of calcium carbonate in nelfinavir-associated diarrhoea in HIV-1-infected patients. HIV Med. 2003, 4, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, N.L.; van Heeswijk, R.P.G.; Foster, B.C.; Akhtar, H.; Singhal, N.; Seguin, I.; DelBalso, L.; Bourbeau, M.; Chauhan, B.M.; Boulassel, M.-R.; et al. The Effect of β-carotene supplementation on the pharmacokinetics of nelfinavir and its active metabolite M8 in HIV-1-infected patients. Molecules 2012, 17, 688–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdissa, A.; Olsen, M.F.; Yilma, D.; Tesfaye, M.; Girma, T.; Christiansen, M.; Hagen, C.; Wiesner, L.; Castel, S.; Aseffa, A.; et al. Lipid-based nutrient supplements do not affect efavirenz but lower plasma nevirapine concentrations in Ethiopian adult HIV patients. HIV Med. 2015, 16, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkombwe, D.; Muungo, T.L.; Michelo, C.; Kelly, P.; Chirwa, S.; Filteau, S. Lipid-based nutrient supplements containing vitamins and minerals attenuate renal electrolyte loss in HIV/AIDS patients starting antiretroviral therapy: A randomized controlled trial in Zambia. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2016, 13, e8–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskapan, A.; Dijkema, D.; de Weerd, D.A.; Bierman, W.F.W.; Kosterink, J.G.W.; van der Werf, T.S.; Alffenaar, J.-W.C.; Stienstra, Y. Food intake and darunavir plasma concentrations in people living with HIV in an outpatient setting. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 2325–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Recommendations on Testing for Funnel Plot Asymmetry. Available online: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_10/10_4_3_1_recommendations_on_testing_for_funnel_plot_asymmetry.htm (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Barry, M.; Gibbons, S.; Back, D.; Mulcahy, F. Protease inhibitors in patients with HIV disease. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1997, 32, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, J.; Imam, S.Z. Medicinal importance of grapefruit juice and its interaction with various drugs. Nutr. J. 2007, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boffito, M.; Acosta, E.; Burger, D.; Fletcher, C.V.; Flexner, C.; Garaffo, R.; Gatti, G.; Kurowski, M.; Perno, C.F.; Peytavin, G.; et al. Part 1 Current status and future prospects of therapeutic drug monitoring and applied clinical pharmacology in antiretroviral therapy. Antivir. Ther. 2005, 10, 375–392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Usach, I.; Melis, V.; Peris, J.-E. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors: A review on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety and tolerability. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SUSTIVA®. (Efavirenz) Capsules and Tablets. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/020972s030,021360s019lbl.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Holec, A.D.; Mandal, S.; Prathipati, P.K.; Destache, C.J. Nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors: A thorough review, present status and future perspective as HIV therapeutics. Curr. HIV Res. 2017, 15, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annex, I. Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/descovy-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Highlights of Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/204790lbl.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Starup-Linde, J.; Rosendahl, S.B.; Storgaard, M.; Langdahl, B. Management of osteoporosis in patients living with HIV—A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 83, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Itoh, S.; Ohgiya, S.; Ishizaki, K.; Kamataki, T. Regulation of CYP1A and CYP3A mRNAs by ascorbic acid in guinea pigs. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1997, 348, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannoni, V.G.; Flynn, E.J.; Lynch, M. Ascorbic acid and drug metabolism. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1972, 21, 1377–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, P.H.; Zannoni, V.G. Stimulation of drug metabolism by ascorbic acid in weanling guinea pigs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974, 23, 3121–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikans, L.E.; Smith, C.R.; Zannoni, V.G. Ascorbic acid and cytochrome P-450. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1978, 204, 702–713. [Google Scholar]

- Netke, S.P.; Roomi, M.W.; Tsao, C.; Niedzwiecki, A. Ascorbic acid protects guinea pigs from acute aflatoxin toxicity. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1997, 143, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heeswijk, R.P.G.; Cooper, C.L.; Foster, B.C.; Chauhan, B.M.; Shirazi, F.; Seguin, I.; Phillips, E.J.; Mills, E. Effect of high-dose vitamin C on hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 activity. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2005, 25, 1725–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, B.C.; Foster, M.S.; VandenHoek, S.; Krantis, A.; Budzinski, J.W.; Arnason, J.T.; Gallicano, K.D.; Choudri, S. An in vitro evaluation of human cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein inhibition by garlic. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2001, 4, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ho, B.E.; Shen, D.D.; McCune, J.S.; Bui, T.; Risler, L.; Yang, Z.; Ho, R.J.Y. Effects of garlic on cytochromes P450 2C9- and 3A4-mediated drug metabolism in human hepatocytes. Sci. Pharm. 2010, 78, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacek, H.; Rentsch, K.M.; Steinert, H.C.; Pauli-Magnus, C.; Meier, P.J.; Fattinger, K. No effect of garlic extract on saquinavir kinetics and hepatic CYP3A4 function measured by the erythromycin breath test. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 75, P80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obach, R.S. Inhibition of human cytochrome P450 enzymes by constituents of St. John’s Wort, an herbal preparation used in the treatment of depression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 294, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Limtrakul, P.; Khantamat, O.; Pintha, K. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein function and expression by kaempferol and quercetin. J. Chemother. 2005, 17, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinozuka, K.; Umegaki, K.; Kubota, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Mizuno, H.; Yamauchi, J.; Nakamura, K.; Kunitomo, M. Feeding of Ginkgo biloba extract (GBE) enhances gene expression of hepatic cytochrome P-450 and attenuates the hypotensive effect of nicardipine in rats. Life Sci. 2002, 70, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Tanaka, N.; Nakamura, K.; Kunitomo, M.; Umegaki, K.; Shinozuka, K. Interaction of Ginkgo biloba extract (GBE) with hypotensive agent, nicardipine, in rats. In Vivo 2003, 17, 409–412. [Google Scholar]

- Malati, C.Y.; Robertson, S.M.; Hunt, J.D.; Chairez, C.; Alfaro, R.M.; Kovacs, J.A.; Penzak, S.R. Influence of Panax ginseng on cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) activity in healthy participants. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 52, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, B.; Francovic, A.; Drouin, C.; Akhtar, H.; Cameron, W. Trans-b-carotene and retinoids can effect human cytochrome p450 3a4-mediated metabolism (Abstract tupeb4564). In Proceedings of the XIV International AIDS Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 7–12 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sczech, R.; Landes, N.; Pfluger, P.; Kluth, D.; Schweigert, F.J. Carotenoids and their metabolites are naturally occurring activators of gene expression via the pregnane X receptor. Eur. J. Nutr. 2004, 43, 336–343. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Year of Publication | Study Setting | Study Design | Study Participants | Food or Dietary Supplements | Antiretroviral Drugs | Major Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kupferschmidt et al., 1998 [24] | Switzerland | Open crossover study | 8 healthy male subjects, mean age 26 ± 2 years | 400 mL grapefruit juice (Hitchcock, freshly prepared), taken 45 min and 15 min before intravenous or oral saquinavir | 12 mg intravenous saquinavir or 600 mg oral saquinavir |

|

| Moore et al., 1999 [14] | United States of America | Single-center, open-label, randomized, three-way crossover study | 24 healthy subjects, mean age 26 ± 4.4 years | The standardized high-fat breakfast: 2 slices of toasted white bread with butter, 2 eggs fried in butter, 2 slices of bacon, 2 ounces of hash-browned potatoes, and 8 ounces of whole milk | 150 mg lamivudine, 300 mg zidovudine, taken within 5 min after breakfast |

|

| Yuen et al., 2001 [25] | United States of America | Single-center, open-label, randomized, three-way crossover study | 24 healthy subjects, mean age 37.6 ± 9.6 years | The standardized high-fat breakfast: 2 slices of toasted white bread with butter, 2 eggs fried in butter, 2 slices of bacon, 2 ounces of hash-browned potatoes, and 8 ounces of whole milk | 300 mg abacavir, 150 mg lamivudine, 300 mg zidovudine, taken within 5 min after breakfast |

|

| Penzak et al., 2002 [26] | United States of America | Open-label, randomized, crossover study | 13 healthy subjects, mean age 24 ± 1.9 years | 8 ounces of Seville® orange juice (prepared by squeezing fresh fruit) or grapefruit juice (prepared from frozen concentrate), taken together with indinavir | 800 mg indinavir |

|

| Falcoz et al., 2002 [27] | Germany | Study A: Single-center, open-label, single-dose, randomized, five-way crossover study | 16 healthy male subjects, age range 24–50 years | The standardized high-fat breakfast: 2 slices of toasted white bread with butter, 2 eggs fried in butter, 2 slices of bacon, 2 ounces of hash-browned potatoes, and a glass of whole milk | 1656 mg GW433908A, 1728 mg GW433908G (taken within 5 min after breakfast), 2592 mg GW433908G, 1200 mg amprenavir |

|

| Study B: Open-label, single-dose, randomized, six-way crossover bioequivalence study | 24 healthy male subjects, age range 19–48 years |

| 1728 mg GW433908G (taken after low- or high-fat meal), 1200 mg amprenavir (taken after low-fat meal) | |||

| Piscitelli et al., 2002 [28] | United States of America | Two-treatment, 3-period, single-sequence, longitudinal study | 9 healthy subjects, mean age 38 ± 7.8 years | Garlic caplet | 1200 mg saquinavir, taken together with garlic | In the presence of garlic, the mean saquinavir AUC0–8, Ctrough, and Cmax were decreased. |

| Slain et al., 2005 [29] | United States of America | Prospective, open-label, longitudinal, two-period time series | 7 healthy subjects, mean age 23.4 ± 1.6 years | 1000 mg vitamin C | 800 mg indinavir, taken at least 3 h separately from vitamin C | High doses of vitamin C can significantly reduce steady-state indinavir plasma concentrations by 20%. |

| Mouly et al., 2005 [30] | United States of America | Randomized, 2-phase, crossover study | 20 healthy subjects, mean age 28 ± 9 years | Seville® orange juice (prepared by squeezing fruit) | 600 mg saquinavir | Seville® orange juice delayed absorption of saquinavir (prolonged tmax). |

| DiCenzo et al., 2006 [31] | New York, United States of America | Prospective pharmacokinetic analysis | 10 healthy subjects, mean age 30.7 ± 9.4 years | 500 mg quercetin with food (standardized light breakfast of 40 g of Cheerios® cereal, 350 g of 2% milk, 43 g of toasted white bread, 9 g of margarine, and 4 g of sugar.) | 1200 mg saquinavir, taken together with quercetin | Administration of quercetin did not influence plasma saquinavir concentration. |

| Sekar et al., 2007 [32] | Belgium | Open-label, 2-panel, randomized, 3-way crossover study | 22 healthy subjects, median age 32 (2–50) years males, 49 (34–55) years females |

| 100 mg ritonavir bd on days 1 to 5, with a single 400 mg darunavir given on day 3 (darunavir/ritonavir), taken immediately after meal | Administration of darunavir/ritonavir in a fasting state resulted in a decrease in darunavir Cmax and AUClast of approximately 30% compared with administration after a standard meal. |

| Robertson et al., 2008 [33] | United States of America | Single-center, open-label | 14 healthy subjects, mean age 29.5 (23–48) years | 120 mg Ginkgo biloba | 400 mg lopinavir/100 mg ritonavir, taken together with Ginkgo biloba extract | Neither lopinavir nor ritonavir pharmacokinetic parameters were significantly changed by 2 weeks of Ginkgo biloba extract coadministration. |

| Patel et al., 2011 [34] | - | Open-label, randomized, crossover study | 16 healthy subjects, mean age 30.8 years | Multivitamin tablet (162 mg of elemental calcium and 100 mg of magnesium per tablet, in addition to iron, zinc, and copper) | 50 mg S/GSK1349572, taken together with multivitamin tablet | Multivitamins did not significantly affect S/GSK1349572 pharmacokinetics. Therefore, they may be co-administered. |

| Calderõn et al., 2014 [35] | United States of America | Single sequence, open-label, single-center pharmacokinetic investigation | 12 healthy subjects, median age 32 (23–42) years | 500 mg Panax ginseng | 400 mg lopinavir/100 mg ritonavir, taken together with Panax ginseng | Neither lopinavir nor ritonavir pharmacokinetic parameters were changed by two weeks of Panax ginseng administration. |

| Song et al., 2015 [36] | United States of America | Open-label, randomized, 2-cohort, 4-period crossover study | 21 healthy subjects, mean age 33.2 years | 1200 mg Calcium carbonate/324 mg Ferrous fumarate | 50 mg dolutegravir, taken together with Calcium or iron supplements |

|

| Buchanan et al., 2017 [37] | United States of America | Phase 1, single-center, randomized, open-label, 5-period crossover study | 15 healthy subjects, mean age 39.8 ± 12.5 years | High-mineral content water (Contrex®: calcium 468 mg/L, magnesium 74.5 mg/L), Low-mineral content water (5% Contrex® in purified water) | 20 mg dolutegravir (dispersed in 12.5 mL of high- or low-mineral water | Dolutegravir pharmacokinetic parameters were unaffected by mineral contents in water. |

| Yamada et al., 2018 [38] | Japan | Open-label, randomized, single-dose, 3-treatment, 3-period, 3-sequence crossover study | 12 healthy male subjects, mean age 32 ± 6.8 years |

| 150 mg elvitegravir, 150 mg cobicistat, 200 mg emtricitabine, 10 mg tenofovir alafenamide, taken within 5 min after breakfast | Food or a nutritional protein-rich drink did not affect the bioavailability of study drugs. |

| Yonemura et al., 2018 [39] | Japan | Open-label, randomized, single-dose, 3-treatment, 3-period, 3-sequence crossover study | 12 healthy male subjects, mean age 30.7 ± 6.4 years |

| Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, taken within 5 min after supplements |

|

| Carver et al., 1999 [12] | United States of America | Four-way crossover study | 7 male PLWH, mean age 41 ± 18 years | Protein, carbohydrate, fat, HPMC separately provided in the form of low viscosity liquid meals, administered 15 min before indinavir | 200 mg indinavir |

|

| Jensen-Fangel et al., 2003 [40] | Denmark | Open-label prospective randomized trial pilot study | 15 PLWH on nelfinavir and reported chronic diarrhea, median age 51 (32–66) years | 1350 mg calcium carbonate or calcium gluconate 1950/calcium carbonate 300 mg | 1250 mg nelfinavir | There were no significant changes in plasma concentration (C0h and C3h) of nelfinavir and its active metabolite M8. |

| Roberts et al., 2011 [15] | United States of America | Case report | An HIV-infected man | Calcium carbonate 1 g vitamin D3 400 IU (cholecalciferol) | 400 mg raltegravir/200 mg emtricitabine + 300 mg tenofovir disoproxil fumarate |

|

| Sheehan et al., 2012 [41] | Canada | Multi-center, open-label, non-randomized steady-state pharmacokinetic study | 11 PLWH receiving nelfinavir 1250 mg twice daily with at least two NRTIs for at least two weeks, mean age 45.5 ± 9.4 years | β-carotene 25,000 IU, taken together with nelfinavir | 1250 mg nelfinavir |

|

| Abdissa et al., 2015 [42] | Ethiopia | Double-blinded, randomized trial | 282 ART-naïve PLWH, mean age 32.2 ± 8.0 years (LNS/w), 34.5 ± 10.3 years (LNS/s), 31.7±8.5 years (no LNS) | Lipid-based nutrient supplement containing whey (LNS/w) Lipid-based nutrient supplement containing soy (LNS/s) | 600 mg efavirenz/200 mg nevirapine |

|

| Munkombwe et al., 2016 [43] | Zambia | Randomized controlled trial | 130 ART-naïve malnourished PLWH (BMI < 18kg/m2), mean age 35 ± 8 years (LNS), 38 ± 9 years (LNS-VM) | Lipid-based nutrient supplements (LNS) or LNS with vitamins and minerals (LNS-VM) | 300 mg tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/200 mg emtricitabine/600 mg efavirenz | The LNS-VM regimen appeared to offer protection against phosphate and potassium loss during HIV/AIDS treatment. |

| Daskapan et al., 2017 [44] | The Netherlands | Cross-sectional study (short report) | 60 PLWH receiving darunavir/ritonavir 800/100 mg od, median age 45 (20–66) years | Main meal/between-meal snack | 800 mg darunavir/100 mg ritonavir | Concurrent food intake did not affect darunavir trough concentrations. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siritientong, T.; Thet, D.; Methaneethorn, J.; Leelakanok, N. Pharmacokinetic Outcomes of the Interactions of Antiretroviral Agents with Food and Supplements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030520

Siritientong T, Thet D, Methaneethorn J, Leelakanok N. Pharmacokinetic Outcomes of the Interactions of Antiretroviral Agents with Food and Supplements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(3):520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030520

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiritientong, Tippawan, Daylia Thet, Janthima Methaneethorn, and Nattawut Leelakanok. 2022. "Pharmacokinetic Outcomes of the Interactions of Antiretroviral Agents with Food and Supplements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 14, no. 3: 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030520

APA StyleSiritientong, T., Thet, D., Methaneethorn, J., & Leelakanok, N. (2022). Pharmacokinetic Outcomes of the Interactions of Antiretroviral Agents with Food and Supplements: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(3), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030520