Variability in Sleep Timing and Dietary Intake: A Scoping Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Literature Search

2.3. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.4. Data Charting Process, and Data Items

2.5. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.6. Synthesis of the Results

3. Results

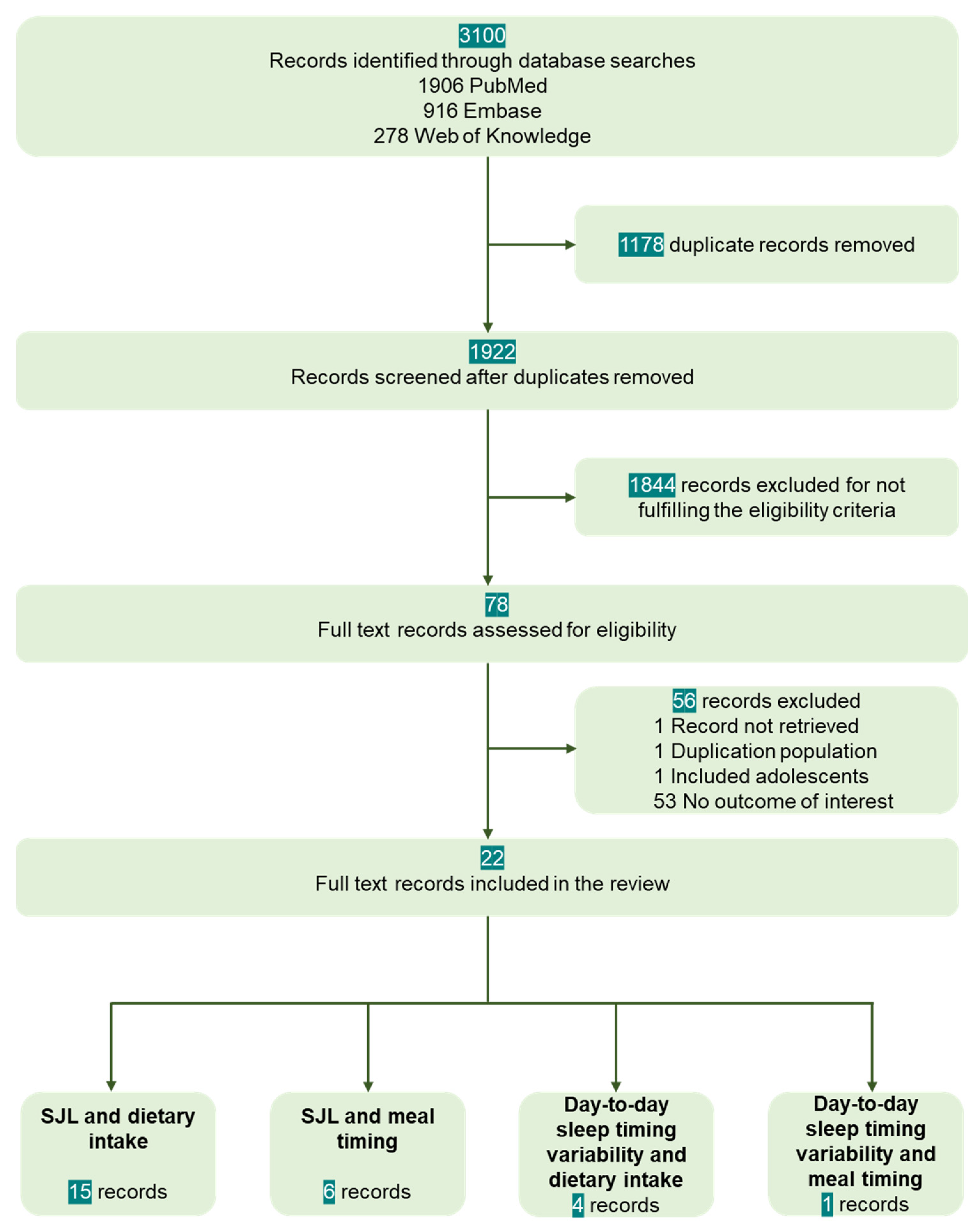

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Assessment of Sleep Timing Variability and Dietary Intake

3.4. SJL and Dietary Intake

3.5. SJL and Meal Timing

3.6. Day-to-Day Variability in Sleep Timing, Dietary Intake, and Meal Timing

3.7. Critical Appraisal of the Individual Sources of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings Related to Research Question and Discussion of Specific Findings

4.2. Gaps Identified in the Sources Included, Implications for Future Studies

4.3. Limitations of the Scoping Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. PubMed

- -

- (“eating”[MeSH Terms] OR “eating”[All Fields] OR (“food”[All Fields] AND “intake”[All Fields]) OR “food intake”[All Fields]) AND ((“social behavior”[MeSH Terms] OR (“social”[All Fields] AND “behavior”[All Fields]) OR “social behavior”[All Fields] OR “sociality”[All Fields] OR “social”[All Fields] OR “socialisation”[All Fields] OR “socialization”[MeSH Terms] OR “socialization”[All Fields] OR “socialise”[All Fields] OR “socialised”[All Fields] OR “socialising”[All Fields] OR “socialities”[All Fields] OR “socializations”[All Fields] OR “socialize”[All Fields] OR “socialized”[All Fields] OR “socializers”[All Fields] OR “socializes”[All Fields] OR “socializing”[All Fields] OR “socially”[All Fields] OR “socials”[All Fields]) AND (“jet lag syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“jet”[All Fields] AND “lag”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “jet lag syndrome”[All Fields] OR “jetlag”[All Fields]))

- -

- (“eating”[MeSH Terms] OR “eating”[All Fields] OR (“dietary”[All Fields] AND “intake”[All Fields]) OR “dietary intake”[All Fields]) AND ((“social behavior”[MeSH Terms] OR (“social”[All Fields] AND “behavior”[All Fields]) OR “social behavior”[All Fields] OR “sociality”[All Fields] OR “social”[All Fields] OR “socialisation”[All Fields] OR “socialization”[MeSH Terms] OR “socialization”[All Fields] OR “socialise”[All Fields] OR “socialised”[All Fields] OR “socialising”[All Fields] OR “socialities”[All Fields] OR “socializations”[All Fields] OR “socialize”[All Fields] OR “socialized”[All Fields] OR “socializers”[All Fields] OR “socializes”[All Fields] OR “socializing”[All Fields] OR “socially”[All Fields] OR “socials”[All Fields]) AND (“jet lag syndrome”[MeSH Terms] OR (“jet”[All Fields] AND “lag”[All Fields] AND “syndrome”[All Fields]) OR “jet lag syndrome”[All Fields] OR “jetlag”[All Fields]))

- -

- (“sleep”[MeSH Terms] OR “sleep”[All Fields] OR “sleeping”[All Fields] OR “sleeps”[All Fields] OR “sleep s”[All Fields]) AND (“variabilities”[All Fields] OR “variability”[All Fields] OR “variable”[All Fields] OR “variable s”[All Fields] OR “variables”[All Fields] OR “variably”[All Fields]) AND (“eating”[MeSH Terms] OR “eating”[All Fields] OR (“dietary”[All Fields] AND “intake”[All Fields]) OR “dietary intake”[All Fields])

- -

- (“sleep”[MeSH Terms] OR “sleep”[All Fields] OR “sleeping”[All Fields] OR “sleeps”[All Fields] OR “sleep s”[All Fields]) AND (“variabilities”[All Fields] OR “variability”[All Fields] OR “variable”[All Fields] OR “variable s”[All Fields] OR “variables”[All Fields] OR “variably”[All Fields]) AND (“eating”[MeSH Terms] OR “eating”[All Fields] OR (“food”[All Fields] AND “intake”[All Fields]) OR “food intake”[All Fields])

- -

- (“eating”[MeSH Terms] OR “eating”[All Fields] OR (“dietary”[All Fields] AND “intake”[All Fields]) OR “dietary intake”[All Fields]) AND ((“regular”[All Fields] OR “regularities”[All Fields] OR “regularity”[All Fields] OR “regularization”[All Fields] OR “regularizations”[All Fields] OR “regularize”[All Fields] OR “regularized”[All Fields] OR “regularizer”[All Fields] OR “regularizers”[All Fields] OR “regularizes”[All Fields] OR “regularizing”[All Fields] OR “regulars”[All Fields]) AND (“sleep”[MeSH Terms] OR “sleep”[All Fields] OR “sleeping”[All Fields] OR “sleeps”[All Fields] OR “sleep s”[All Fields]))

- -

- ((“eating”[MeSH Terms] OR “eating”[All Fields] OR (“food”[All Fields] AND “intake”[All Fields]) OR “food intake”[All Fields]) AND ((“regular”[All Fields] OR “regularities”[All Fields] OR “regularity”[All Fields] OR “regularization”[All Fields] OR “regularizations”[All Fields] OR “regularize”[All Fields] OR “regularized”[All Fields] OR “regularizer”[All Fields] OR “regularizers”[All Fields] OR “regularizes”[All Fields] OR “regularizing”[All Fields] OR “regulars”[All Fields]) AND (“sleep”[MeSH Terms] OR “sleep”[All Fields] OR “sleeping”[All Fields] OR “sleeps”[All Fields] OR “sleep s”[All Fields])))

Appendix A.2. Embase

- -

- (‘social jetlag’/exp OR ‘social jetlag’) AND (‘food intake’/exp OR ‘food intake’) AND [<1966–2021]/py

- -

- (‘social jetlag’/exp OR ‘social jetlag’) AND (‘dietary intake’/exp OR ‘dietary intake’) AND [<1966–2021]/py

- -

- (‘sleep’/exp OR sleep) AND (‘variability’/exp OR variability) AND (‘food intake’/exp OR ‘food intake’) AND [<1966–2021]/py

- -

- (‘sleep’/exp OR sleep) AND (‘variability’/exp OR variability) AND (‘dietary intake’/exp OR ‘dietary intake’) AND [<1966–2021]/py

- -

- (‘sleep’/exp OR ‘sleep’) AND ‘regularity’ AND (‘food intake’/exp OR ‘food intake’) AND [<1966–2021]/py

- -

- (‘sleep’/exp OR ‘sleep’) AND ‘regularity’ AND (‘dietary intake’/exp OR ‘dietary intake’) AND [<1966–2021]/py

Appendix A.3. Clarivate Analytics Web of Science

- -

- social jetlag (All Fields) AND food intake (All Fields)

- -

- social jetlag (All Fields) AND dietary intake (All Fields)

- -

- sleep (All Fields) AND variability (All Fields) AND food intake (All Fields)

- -

- sleep (All Fields) AND variability (All Fields) AND dietary intake (All Fields)

- -

- sleep (All Fields) and regularity (All Fields) and food intake (All Fields)

- -

- sleep (All Fields) and regularity (All Fields) and dietary intake (All Fields)

References

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Allen, N.B.; Anderson, C.; Black, T.; Brewer, L.C.; Foraker, R.E.; Grandner, M.A.; Lavretsky, H.; Perak, A.M.; Sharma, G.; et al. Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146, e18–e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J. Sleep health: Can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep 2014, 37, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.S.; Kontopantelis, E.; Kuligowski, G.; Gray, M.; Muhyaldeen, A.; Gale, C.P.; Peat, G.M.; Cleator, J.; Chew-Graham, C.; Loke, Y.K.; et al. Self-Reported Sleep Duration and Quality and Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacaro, V.; Ballesio, A.; Cerolini, S.; Vacca, M.; Poggiogalle, E.; Donini, L.M.; Lucidi, F.; Lombardo, C. Sleep duration and obesity in adulthood: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wittmann, M.; Dinich, J.; Merrow, M.; Roenneberg, T. Social jetlag: Misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol. Int. 2006, 23, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Allebrandt, K.V.; Merrow, M.; Vetter, C. Social jetlag and obesity. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliandro, R.; Streng, A.A.; van Kerkhof, L.W.M.; van der Horst, G.T.J.; Chaves, I. Social Jetlag and Related Risks for Human Health: A Timely Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bei, B.; Wiley, J.F.; Trinder, J.; Manber, R. Beyond the mean: A systematic review on the correlates of daily intraindividual variability of sleep/wake patterns. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 28, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavish, D.C.; Taylor, D.J.; Lichstein, K.L. Intraindividual variability in sleep and comorbid medical and mental health conditions. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, D.; Klerman, E.B.; Phillips, A.J. Measuring sleep regularity: Theoretical properties and practical usage of existing metrics. Sleep 2021, 44, zsab103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuraikat, F.M.; Makarem, N.; Redline, S.; Aggarwal, B.; Jelic, S.; St-Onge, M.P. Sleep Regularity and Cardiometabolic Heath: Is Variability in Sleep Patterns a Risk Factor for Excess Adiposity and Glycemic Dysregulation? Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2020, 20, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.P.; McHill, A.W.; Cox, R.C.; Broussard, J.L.; Dutil, C.; da Costa, B.G.G.; Sampasa-Kanyinga, H.; Wright, K.P., Jr. The role of insufficient sleep and circadian misalignment in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, W.L. The emerging importance of tackling sleep-diet interactions in lifestyle interventions for weight management. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Miami, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Kawasaki, Y.; Akamatsu, R.; Fujiwara, Y.; Omori, M.; Sugawara, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; Iwakabe, S.; Kobayashi, T. Later chronotype is associated with unhealthful plant-based diet quality in young Japanese women. Appetite 2021, 166, 105468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, S.A.; Oswald, L.B.; Reid, K.J.; Baron, K.G. Do Physical Activity, Caloric Intake, and Sleep Vary Together Day to Day? Exploration of Intraindividual Variability in 3 Key Health Behaviors. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J.; Kline, C.E.; Rebar, A.L.; Vandelanotte, C.; Short, C.E. Greater bed- and wake-time variability is associated with less healthy lifestyle behaviors: A cross-sectional study. J. Public Health 2016, 24, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, M.; Baspinar, B.; Özçelik, A. A cross-sectional evaluation of the relationship between social jetlag and diet quality. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anothaisintawee, T.; Lertrattananon, D.; Thamakaison, S.; Thakkinstian, A.; Reutrakul, S. The Relationship Among Morningness-Eveningness, Sleep Duration, Social Jetlag, and Body Mass Index in Asian Patients with Prediabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Liu, D.Y.; Sheng, L.L.; Xiao, H.; Chao, Y.M.; Zhao, Y. Chronotype and sleep duration are associated with stimulant consumption and BMI among Chinese undergraduates. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2018, 16, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, G.; Cade, J.; Hardie, L. Sleeping and eating timing in UK adults: Associations with metabolic health and physical activity. Sleep Med. 2017, 40, e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polugrudov, A.; Popov, S.; Smirnov, V.; Panev, A.; Ascheulova, E.; Kuznetsova, E.; Tserne, T.; Borisenkov, M. Association of social jetlag experienced by young northerners with their appetite after having breakfast. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2017, 48, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanes, M.; Jones, K.; Rebellon, C.; Zaman, A.; Thomas, E.; Rynders, C. Associations among dietary quality, meal timing, and sleep in adults with overweight and obesity. Obesity 2020, 28, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R.M.; Finn, J.; Healy, U.; Gallen, D.; Sreenan, S.; McDermott, J.H.; Coogan, A.N. Greater social jetlag associates with higher HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes: A cross sectional study. Sleep Med. 2020, 66, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota, M.C.; Silva, C.M.; Balieiro, L.C.T.; Gonçalves, B.F.; Fahmy, W.M.; Crispim, C.A. Association between social jetlag food consumption and meal times in patients with obesity-related chronic diseases. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, A.; Ciobanu, D.; Vonica, C.L.; Bala, C.; Mocan, A.; Sima, D.; Inceu, G.; Craciun, A.; Pop, R.M.; Craciun, C.; et al. Chronic disruption of circadian rhythm with mistimed sleep and appetite—An exploratory research. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.M.; Mota, M.C.; Miranda, M.T.; Paim, S.L.; Waterhouse, J.; Crispim, C.A. Chronotype, social jetlag and sleep debt are associated with dietary intake among Brazilian undergraduate students. Chronobiol. Int. 2016, 33, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suikki, T.; Maukonen, M.; Partonen, T.; Jousilahti, P.; Kanerva, N.; Männistö, S. Association between social jet lag, quality of diet and obesity by diurnal preference in Finnish adult population. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizaki, T.; Togo, F. Objectively measured chronotype and social jetlag are associated with habitual dietary intake in undergraduate students. Nutr. Res. 2021, 90, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerón-Rugerio, M.F.; Cambras, T.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Social Jet Lag Associates Negatively with the Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Body Mass Index among Young Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerón-Rugerio, M.F.; Hernáez, Á.; Porras-Loaiza, A.P.; Cambras, T.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Eating Jet Lag: A Marker of the Variability in Meal Timing and Its Association with Body Mass Index. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.S. Daily associations between objective sleep and consumption of highly palatable food in free-living conditions. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2018, 4, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almoosawi, S.; Palla, L.; Walshe, I.; Vingeliene, S.; Ellis, J.G. Long Sleep Duration and Social Jetlag Are Associated Inversely with a Healthy Dietary Pattern in Adults: Results from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme Y1–4. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, M.; Uemura, H.; Katsuura-Kamano, S.; Nakamoto, M.; Hiyoshi, M.; Takami, H.; Sawachika, F.; Juta, T.; Arisawa, K. Relationship of dietary factors and habits with sleep-wake regularity. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 22, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnaranta, O.; Bourguignon, C.; Crescenzi, O.; Sibthorpe, D.; Buyukkurt, A.; Steiger, H.; Storch, K.F. Late and Instable Sleep Phasing is Associated with Irregular Eating Patterns in Eating Disorders. Ann. Behav. Med. 2020, 54, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.C.; Mota, M.C.; Marot, L.P.; Mattar, L.A.; de Sousa, J.A.G.; Araújo, A.C.T.; da Costa Assis, C.T.; Crispim, C.A. Circadian Misalignment Is Negatively Associated with the Anthropometric, Metabolic and Food Intake Outcomes of Bariatric Patients 6 Months After Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Morris, C.J.; Caputo, R.; Wang, W.; Garaulet, M.; Scheer, F.A.J.L. Sex differences in the circadian misalignment effects on energy regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23806–23812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.C.; Centofanti, S.; Dorrian, J.; Coates, A.M.; Stepien, J.M.; Kennaway, D.; Wittert, G.; Heilbronn, L.; Catcheside, P.; Noakes, M.; et al. Subjective Hunger, Gastric Upset, and Sleepiness in Response to Altered Meal Timing during Simulated Shiftwork. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHill, A.W.; Hull, J.T.; Klerman, E.B. Chronic Circadian Disruption and Sleep Restriction Influence Subjective Hunger, Appetite, and Food Preference. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechifor, R.E.; Ciobanu, D.; Vonica, C.L.; Popita, C.; Roman, G.; Bala, C.; Mocan, A.; Inceu, G.; Craciun, A.; Rusu, A. Social jetlag and sleep deprivation are associated with altered activity in the reward-related brain areas: An exploratory resting-state fMRI study. Sleep Med. 2020, 72, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, A.E.; Baldo, B.A.; Pratt, W.E.; Will, M.J. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: Integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 86, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, G.J.; Meek, T.H.; Schwartz, M.W. Neurobiology of food intake in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nectow, A.R.; Schneeberger, M.; Zhang, H.; Field, B.C.; Renier, N.; Azevedo, E.; Patel, B.; Liang, Y.; Mitra, S.; Tessier-Lavigne, M.; et al. Identification of a Brainstem Circuit Controlling Feeding. Cell 2017, 170, 429–442.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, D.C.; Cole, S.L.; Berridge, K.C. Lateral hypothalamus, nucleus accumbens, and ventral pallidum roles in eating and hunger: Interactions between homeostatic and reward circuitry. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkow, N.D.; Wise, R.A.; Baler, R. The dopamine motive system: Implications for drug and food addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittendrigh, C.S. Temporal organization: Reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1993, 55, 16–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J. Food intake and addictive-like eating behaviors: Time to think about the circadian clock(s). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 106, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainier, C.; Mateo, M.; Felder-Schmittbuhl, M.P.; Mendoza, J. Circadian rhythms of hedonic drinking behavior in mice. Neuroscience 2017, 349, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tõnissaar, M.; Herm, L.; Rinken, A.; Harro, J. Individual differences in sucrose intake and preference in the rat: Circadian variation and association with dopamine D2 receptor function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 403, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeman, I.; Smith, H.A.; Walhin, J.P.; Middleton, B.; Gonzalez, J.T.; Karagounis, L.G.; Johnston, J.D.; Betts, J.A. Unacylated ghrelin, leptin, and appetite display diurnal rhythmicity in lean adults. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 1534–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.Y. Organization of the mammalian circadian system. Ciba Found. Symp. 1995, 183, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vujovic, N.; Gooley, J.J.; Jhou, T.C.; Saper, C.B. Projections from the subparaventricular zone define four channels of output from the circadian timing system. J. Comp. Neurol. 2015, 523, 2714–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellinger, L.L.; Bernardis, L.L. The dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus and its role in ingestive behavior and body weight regulation: Lessons learned from lesioning studies. Physiol. Behav. 2002, 76, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, C.C.; Coates, A.M.; Dorrian, J.; Banks, S. The factors influencing the eating behaviour of shiftworkers: What, when, where and why. Ind. Health 2019, 57, 419–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHill, A.W.; Melanson, E.L.; Higgins, J.; Connick, E.; Moehlman, T.M.; Stothard, E.R.; Wright, K.P., Jr. Impact of circadian misalignment on energy metabolism during simulated nightshift work. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17302–17307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arble, D.M.; Bass, J.; Laposky, A.D.; Vitaterna, M.H.; Turek, F.W. Circadian timing of food intake contributes to weight gain. Obesity 2009, 17, 2100–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonken, L.K.; Workman, J.L.; Walton, J.C.; Weil, Z.M.; Morris, J.S.; Haim, A.; Nelson, R.J. Light at night increases body mass by shifting the time of food intake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18664–18669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romon, M.; Edme, J.L.; Boulenguez, C.; Lescroart, J.L.; Frimat, P. Circadian variation of diet-induced thermogenesis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993, 57, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, K.G.; Reid, K.J.; Kern, A.S.; Zee, P.C. Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity 2011, 19, 1374–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Panda, S. A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans that Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, K.S. Social jet lag: Sleep-corrected formula. Chronobiol. Int. 2017, 34, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Pilz, L.K.; Zerbini, G.; Winnebeck, E.C. Chronotype and Social Jetlag: A (Self-) Critical Review. Biology 2019, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, M.; Tahara, Y.; Tsubosaka, M.; Fukazawa, M.; Ozaki, M.; Iwakami, T.; Nakaoka, T.; Shibata, S. Chronotype and social jetlag influence human circadian clock gene expression. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roenneberg, T.; Kuehnle, T.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Ricken, J.; Havel, M.; Guth, A.; Merrow, M. A marker for the end of adolescence. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R1038–R1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facer-Childs, E.R.; Middleton, B.; Skene, D.J.; Bagshaw, A.P. Resetting the late timing of “night owls” has a positive impact on mental health and performance. Sleep Med. 2019, 60, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schantz, M.; Taporoski, T.P.; Horimoto, A.R.V.R.; Duarte, N.E.; Vallada, H.; Krieger, J.E.; Pedrazzoli, M.; Negrão, A.B.; Pereira, A.C. Distribution and heritability of diurnal preference (chronotype) in a rural Brazilian family-based cohort, the Baependi study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors, Year | Country | Study Design | Population Sample | Population Type, Gender | Age, Years | SJL Calculation | SJL Assessment Method | Dietary Intake Assessment Method | Main Study Objective | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodur et al., 2021 [20] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 710 | General population, M/F | 19.0–24.0 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire for the previous night | 24 h food recall | Energy, macronutrient intake and diet qualities in persons with and without SJL during working vs. non-working days. | Participants with SJL reported during free days vs. workdays: higher energy intake (1531.4 ± 491.3 kcal/day vs. 1443.5 ± 470.6 kcal/day, p < 0.001) higher amount of total fat (69.22 ± 27.43 g/day vs. 62.5 ± 26.1 g/day, p < 0.001), higher amount of saturated fat (27.6 ± 12.8 g/day vs. 24.0 ± 11.5 g/day, p < 0.001) lower intake of fiber (13.7 ± 6.6 g/day vs. 14.9 ± 7.3 g/day, p = 0.001) higher MUFA intake (24.1 ± 10.3 g/day vs. 21.9 ± 9.8 g/day, p < 0.001) no change in diet quality (HEI 2015 total score 53.06 ± 12.6 vs. 52.6 ± 10.88, p = 0.548) Participants without SJL reported during free days vs. workdays no significant change in energy and macronutrients intake (p > 0.05) and an increase in diet quality (53.15 ± 10.03 vs. 59.30 ± 10.78, p < 0.001) Participants without SJL had significantly higher diet quality (p < 0.001) and higher consumption of fruit (p = 0.010), whole fruit (p = 0.005), whole grain (p = 0.008), and milk (p = 0.043). | Dietary intake assessed for the 24 h before the study visits. Sleep mid-point assessed only for the night before interview. No power calculation. |

| Rusu et al., 2021 [28] | Romania | Cross-sectional | 80 | Healthy normal weight young participants, M/F | 31.7 ± 6.7 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire for the previous month | 24 h food recall VAS for food preferences | Effect of SJL on perceived appetite, hunger, and ghrelin in healthy subjects in free-living conditions. | No difference was observed between participants with/without SJL for caloric intake (1732.3 ± 642.1 kcal/day vs. 1867.1 ± 752.8 kcal/day) calories from, carbohydrates 51.3 (41.9; 57.7)% vs. 50.7 (42.0; 55.5)% of calories from proteins 15.2 (12.1; 18.7)% vs. 17.0 (13.0; 19.9)% calories from fats 37.2 (30.0; 43.6)% vs. 38.3 (31.6; 41.0)% Participants with SJL reported a higher perceived appetite for vegetables, pork, poultry, fish, eggs, milk, and dairy products than those without SJL. | Dietary intake assessed only for the previous 24 h. No power calculation. Small sample. Statistical significance of differences between groups not tested. Young, healthy, highly educated and normal-weight participants. |

| Kawasaki et al., 2021 [17] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 218 | General population, F | 19.9 ± 1.6 20.2 ± 1.9 | MSF-MSW | MCTQ | 54 items FFQ | The association of chronotype with healthful and unhealthful plant-based diet quality | No association of SJL with healthful plant-based diet quality (β = 0.024, p = 0.509) nor with unhealthy plant-based diet quality (β = 0.100, p = 0.141). | Sample size calculation was performed, but not for SJL. Association of SJL with dietary intake not listed among the study objectives. Only young women enrolled. |

| Suikki et al., 2021 [30] | Finland | Cross-sectional | 6779 | General population (FINRISK 2012 and DILGOM 2014), M/F | 25–74 | Time in bed in weekends—time in bed during weekdays | Questionnaire | 131-item FFQ | The association of SJL with diurnal preference, and whether the association of SJL with the quality of the diet and obesity was influenced by diurnal preference. | Participants with a morning chronotype and a SJLsc ≥ 2 h had lower adherence to a healthy Nordic diet than those with a SJLsc < 1 h (BSD scale for adherence 10.5 points vs. 11.8 points, p = 0.006), independent of age, sex, educational years, smoking, leisure-time physical activity, and energy intake. Participants with a morning chronotype and a SJLsc ≥ 2 h consumed less fruits, berries, and cereals, but more alcohol, than those with a SJLsc < 1 h (p < 0.05) independent of age, sex, educational years, smoking, leisure-time physical activity, and energy intake. Total energy intake did not differ between SJLsc groups according to diurnal preference (p = 1.00). | No power calculation. |

| Yoshizaki et al., 2021 [31] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 82 | Young adults | 19–29 | MSF-MSW | 7-day wrist actigraphy | 135-item FFQ | The associations of chronotype and SJL with the quantity and over- all quality of habitual food consumption | A larger SJL was associated with lower total energy intake (β = −0.094, p = 0.013), lower grains consumption (β = −0.143, p < 0.001) and greater consumption of sugar and confectioneries (β = 0.231, p = 0.010) independent of age, sex, BMI, residential status, and WD and WE total sleep duration. | Young, healthy and highly educated participants. |

| Carvalho et al., 2020 [38] | Brazil | Prospective, observational | 122 | Patients with obesity after bariatric surgery, M/F | 33.0 (28.0–41.7) | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire SJL evaluated at 3 visits (3 months interval) and a median exposure to SJL calculated | 24 h food recall at each visit for workdays and free days | The influence of SJL on anthropometric, metabolic and food intake 6 months after the surgical intervention | Participants with larger SJL exposure vs. small SJL exposure had higher intakes of calories (baseline 2565.6 ± 130.0 kcal/day, 3 months 889.7 ± 34.2 kcal/day, 6 months 1091.9 ± 39.0 kcal/day vs. baseline 2185.0 ± 95.5 kcal/day, 3 months 823.8 ± 32.0 kcal/day, 6 months 937.7 ± 30.6 kcal/day; p = 0.001) carbohydrate (baseline 261.4 ± 13.7 g/day, 3 months 70.7 ± 3.7 g/day, 6 months 77.7 ± 3.8 g/day vs. baseline 229.0 ± 9.4 g/day, 3 months 61.0 ± 3.1 g/day, 6 months 68.8 ± 3.5 g/day, p = 0.005) and total fat (baseline 116.5 ± 7.4 g/day, 3 months 33.2 ± 1.9 g/day, 6 months 49.5 ± 2.4 g/day vs. baseline 97.3 ± 5.6 g/day, 3 months 32.2 ± 1.7 g/day, 6 months 40.2 ± 1.7 g/day, p = 0.007) polyunsaturated fat (baseline 15.9 ± 1.2 g/day, 3 months 5.0 ± 0.3 g/day, 6 months 7.8 ± 0.5 g/day vs. baseline 12.9 ± 0.9 g/day, 3 months 4.5 ± 0.2 g/day, 6 months 5.9 ± 0.3 g/day, p < 0.001) and monounsaturated fat (baseline 34.5 ± 1.9 g/day, 3 months 10.2 ± 0.6 g/day, 6 months 15.6 ± 0.9 g/day vs. baseline 30.1 ± 1.9 g/day, 3 months 10.0 ± 0.6 g/day, 6 months 12.8 ± 0.5 g/day, p = 0.035) | Dietary intake assessed only for the previous 24 h. Sample selected from a private clinic and included only those with gastric sleeve or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. |

| Kelly et al., 2020 [26] | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 252 | Type 2 diabetes, M/F | 61.9 ± 10.5 | MSF-MSW | MCTQ | 24h food recall | The association of chronotype and/or SJL with glycemic control. | No difference was observed between SJL groups in: daily caloric intake (SJL < 30 min: 1360.19 ± 284.55 kcal, SJL 30–90 min: 1410.52 ± 470.32 kcal, SJL 90 min: 1273.89 ± 395.82 kcal, p = 0.516), breakfast calories (SJL 30 min: 355.52 ± 123.63 kcal, SJL 30–90 min: 322.87 ± 155.14 kcal, SJL > 90 min: 326.06 ± 186.27 kcal, p = 0.848) lunch calories (SJL < 30 min: 321.00 ± 178.13 kcal, SJL 30–90 min: 397.39 ± 243.41 kcal, SJL > 90 min: 270.44 ± 150.22, p = 0.140) dinner calories (SJL < 30 min: 455.33 ± 191.91 kcal, SJL 30–90 min: 493.83 ± 224.96 kcal, SJL > 90 min: 476.94 ± 234.08, p = 0.913) | Sample size calculation was performed, but not for SJL. Association of SJL with dietary intake not listed as study objective. Dietary intake assessed only for the previous 24 h. |

| Lanes et al., 2020 [25] | US | Cross-sectional | 79 (23 for energy intake) | Patients with overweight and obesity, M/F | 39 ± 8 | Undisclosed | 7 day sleep log | Time-stamped photographic food records for 3 days | The relationships among dietary quality, timing of energy intake, and sleep. | SJL was associated with a higher percentage of fat in the diet (r = 0.55, p = 0.007). No significant associations were found between the diet quality and timing variables. | Very small sample in the analysis on energy intake. No power calculation. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were not available |

| Mota et al., 2019 [27] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 792 | Obesity-related chronic diseases, M/F | 55.9 ± 12.4 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire | 24 h food recall | The association of SJL with food consumption. | After adjustments for, patients with SJL vs. without SJL consumed more: total calories (1621.6 ± 38.1 vs. 1508.3 ± 20.2, p < 0.001) protein (85.1 ± 2.7 g vs. 76.5 ± 1.4 g, p < 0.001) total fat (59.9 ± 2.1 g vs. 52.6 ± 1.0 g, p = 0.002) saturated fat (19.4 ± 0.8 g vs. 17.3 ± 0.4 g, p = 0.01) cholesterol (315.9 ± 14.1 g vs. 246.2 ± 6.3 g, p < 0.001) servings per day of meat and eggs (2.5 ± 0.10 vs. 2.2 ± 0.05, p = 0.002) servings per day of sweets (1.7 ± 0.12 vs. 1.4 ± 0.06, p = 0.04) In the logistic regression SJL was associated with a higher risk of consumption above recommendations for total fat (OR = 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1–1.9; p = 0.03), saturated fat (OR = 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1–2.0; p = 0.01) and cholesterol (OR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.3–2.6; p < 0.001), independent of age, sex, BMI, minutes of physical activity per week, mean sleeping duration and time since diagnosis of T2 D. | No power calculation. Dietary intake assessed only for the previous 24 h. |

| Zeron-Rugerio et al., 2019 [32] | Spain | Cross-sectional | 534 | Healthy young adults, M/F | 18–25 | Time in bed in weekends—time in bed during weekdays | Questionnaire | Mediterranean Diet Quality Index for children and adolescents (KIDMED) | Association of SJL with the adherence to the Mediterranean diet. | Subjects with higher SJL had a lower adherence to Mediterranean diet (β = −0.305, 95% CI: −0.503–−0.107, p = 0.003) independent of age, gender, physical activity, and sleep duration. SJL was associated with a lower intake of fresh or cooked vegetables (less than once a day, p < 0.05) and skipping breakfast (p < 0.05) independent of age, gender, and physical activity. | Young, healthy, and highly educated participants. No power calculation. |

| Almoosawi et al., 2018 [35] | UK | Cross-sectional | 2433 | General population, M/F | 19–64 | Difference in sleep duration between weekends and weekdays | Questionnaire for the past 7 days | Food diary | Association of sleep duration and SJL with dietary patterns. | An inversed u-shaped nonlinear association between SJL and the healthy dietary pattern was observed. Scores for healthy dietary pattern increased up to a SJL duration of 1 h 45 min. Beyond this point the scores declined, showing an inverse association of SJL duration with healthy dietary pattern. This association was independent of potential covariates, including BMI (β for quadratic term = −0.03, 95% CI: −0.04, −0.01, p = 0.006). | No power calculation for the objective of the analysis. |

| Zhang et al., 2018 [22] | China | Cross-sectional | 977 | Young adults, M/F | <19 to >21 | MSF-MSW | MCTQ | Questionnaire on the frequency of stimulant drink consumption | The association between SJL, sleep duration, chronotype and stimulant consumption. | No association of SJL with a higher likelihood of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption was observed in the model adjusted for age, sex, race, grade, the type of university, mother’s education, father’s education, outdoor activities on workdays or free days and average sleep duration (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.72–1.20). | Young, and highly educated participants. No sample size/power calculation. |

| Polugrudov et al., 2017 [24] | Russia | Cross-sectional, experimental | 66 | Healthy normal weight young participants, M/F | 23.2 ± 3.4 | MSF-MSW | MCTQ | VAS for appetite | The impact of SJL on appetite in response to a meal. | Similar caloric intake at test meal in SJL groups (SJL < 1 h: 923.1 ± 77.3 kcal; SJL 1–2 h: 1144.6 ± 79.3 kcal; SJL > 2 h: 1122.1 ± 82.7 kcal). Despite similar caloric intake participants with SJL had higher ratings of hunger and prospective food intake after meal than in the SJL ≤ 1 h group. Post meal mean SQ (mean value of the SQs for hunger, prospective food intake, satiety, and fullness) was significantly lower in participants in the 1 < SJL ≤ 2 h and SJL > 2 h groups (1.3 and 1.7 times, respectively) compared to those in the SJL ≤ 1 h group (p < 0.010). No association of SJL with the desire to eat sweets, salty, fatty, or savoury foods was observed. | No power calculation. Small sample. Young, healthy, highly educated, and normal weight participants. |

| Potter et al., 2017 [23] | UK | Cross-sectional | 72 | General population, M/F | 43.5 ± 16.6 | Undisclosed | MCTQ | 24 h food recall | Association of chronotype and SJL with diet composition, metabolic outcomes, and physical activity. | 1 h increase in SJL was associated with 20 g lower consumption of sugar (95% CI −33 to −6 g, p = 0.004) after adjustment for age, chronotype, ethnicity, and sex. | No power calculation. Small sample. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were not available. |

| Silva et al., 2016 [29] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 204 | Healthy young participants, M/F | 18–39 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire | 70-item FFQ | The relationship between chronotype, SJL, perceived sleep debt and dietary intake. | SJL was negatively associated with servings per day of beans (β = −0.16; p = 0.02), independent of age, BMI, and sex. | No power calculation. Young, healthy, and highly educated participants. |

| Authors, Year | Country | Study Design | Population Sample | Population Type, Gender | Age, Years | SJL Calculation | SJL Assessment Method | Meal Timing Assessment Method | Main Study Objective | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bodur et al., 2021 [19] | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 710 | General population, M/F | 19.0–24.0 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire for the previous night | 24 h food recall | Energy, macronutrient intake and diet qualities in persons with and without SJL during working vs. non-working days. | Delayed meal timing in free days compared to workdays irrespective of SJL presence. Significant difference in the change of breakfast time in those with SJL compared to those without SJL (02:19 vs. 01:29, p < 0.001). A similar eating window was observed in both groups during free and workdays. It decreased significantly during free days in participants with SJL (−01:47 vs. −01:45, p < 0.001) resulting in a shorter eating window in free days in those with SJL as compared to those without SJL Shorter eating window in free days in those with SJL as compared to those without SJL (8:42 vs. 9:07). | Dietary intake assessed for the 24 h prior to the study visits. Sleep mid-point assessed only for the night before interview. No power calculation. |

| Rusu et al., 2021 [28] | Romania | Cross-sectional | 80 | Healthy normal weight young participants, M/F | 31.7 ± 6.7 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire for the previous month | 24 h food recall VAS for food preferences | Effect of SJL on perceived appetite, hunger, and ghrelin in healthy subjects in free-living conditions. | A later lunch and dinner time in group with SJL as compared to group without SJL (14:03 h vs. 13:46 h and 20:00 h vs. 19:38 h, respectively). A higher frequency of snacking after dinner (35.0% vs. 30.0%) and a later time of this snack was observed in participants with SJL than in those without SJL. | Dietary intake assessed only for the previous 24 h. No power calculation. Small sample. Statistical significance of differences between groups not tested. Young, healthy, highly educated, and normal weight participants. |

| Mota et al., 2019 [27] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 792 | Obesity-related chronic diseases, M/F | 55.9 ± 12.4 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire | 24 h food recall | The association of SJL with food consumption. | Patients with SJL had breakfast (7:44 ± 0:04 vs. 7:20 ± 0:02, p = 0.02), early afternoon snack (15:54 ± 0:05 vs. 15:36 ± 0:02, p < 0.001) and dinner time (20:12 ± 0:11 vs. 19:42 ± 0:06, p = 0.01) later than those without SJL. Patients with SJL reported a longer eating window (13:09 ± 0:10 vs. 12:45 ± 0:06, p = 0.03), higher calorie intake after 9 p.m. (188.4 ± 26.9 vs. 105.1 ± 10.2, p < 0.001), and a higher proportion of calories consumed after 9 p.m. (10.5 ± 0.9% vs. 6.2 ± 0.5%, p < 0.001) than those without SJL. | No power calculation. Dietary intake assessed only for the previous 24 h. |

| Zeron Rugerio et al., 2019 [33] | Spain Mexico | Cross-sectional | 1106 | Healthy young participants, M/F | 18–25 | MSF-MSW | MCTQ | Questionnaire | The association of eating jet lag with BMI. | SJL was associated with variability in meal timing (breakfast jetlag β = 0.720, 95% CI: 0.640–0.800, p < 0.00001; lunch jetlag β = 0.049, 95% CI: 0.002–0.096, p = 0.042; dinner jetlag β = 0.072, 95% CI: 0.038–0.110, p < 0.001), and eating jet lag (β = 0.270, 95% CI: 0.210–0.330, p < 0.001) independent of age, gender, nationality, diet quality, sleep duration, and physical activity. | No power calculation. Young healthy and highly educated participants. |

| Anothaisintawee et al., 2018 [21] | Thailand | Cross-sectional | 2133 | Patients with prediabetes, M/F | 32–92 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire | 24 h food recall | The contribution of chronotype to body mass index | A higher SJL was associated with later dinner time. | Association of SJL with meal timing was an incidental finding. No power calculation. |

| Silva et al., 2016 [29] | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 204 | Healthy young participants, M/F | 18–39 | MSF-MSW | Questionnaire | 70-item FFQ | The relationship between chronotype, SJL, perceived sleep debt and dietary intake. | A weak negative correlation between SJL and breakfast time (r = −0.23, p < 0.01) was observed, and this correlation was independent of age. | No power calculation. Young, healthy, and highly educated participants. |

| Authors, Year | Country | Study Design | Population Sample | Population Type, Gender | Age, Years | Metric Used for Sleep Timing Variability | Day-to-Day Sleep Timing Variability Assessment Method | Dietary Intake Assessment Method | Main Study Objective | Main Findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association of Day-to-Day Variability in Sleep Timing with Dietary Intake | |||||||||||

| Hooker et al., 2020 [18] | US | Cross-sectional | 103 | General population, M/F | 18–50 | StDev | 7 days of sleep actigraphy Sleep diaries | 7 days of food diaries | To evaluate the characteristics of health behavior variabilities for 3 key health behaviours: physical activity, caloric intake, and sleep (duration and timing). | No significant correlation of variability in sleep timing with average caloric intake (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.14, p > 0.05) or variability in caloric intake (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.10, p > 0.05) was found. | No power calculation. Young, healthy, highly educated, and highly active participants. |

| Duncan et al., 2016 [19] | Australia | Cross-sectional | 1317 | General population, M/F | 57 (46, 66) | Weighted average | Sleep Timing Questionnaire | 13-item Diet Quality Tool | To examine the relationship of bedtime, rise-time, and variation in these with dietary behaviours, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and partial sleep deprivation. | Bed-time variability was negatively associated with dietary quality (β = 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93–0.99, p = 0.002), independent of waking time variability, usual bedtime and waking time, age, gender, smoking status, number of health conditions, work schedule, BMI, and days of insufficient sleep. | No power calculation. Median age was 57 and thus participants may have a regular sleep pattern. |

| Chan, 2018 [34] | US | Cross-sectional | 78 | Healthy young adults, M/F | 18–30 | Not disclosed | 7 days of sleep actigraphy | 7 days of food diaries | To evaluate the associations of actigraphy-assessed sleep with high palatable food consumption in free-living conditions. | Bedtime variability > 90 min was associated with less frequently high palatable food consumption at breakfast than in those with bedtime variability < 90 min (OR 2.31 vs. 3.78, p = 0.004). There was no difference at lunch and dinner. | No power calculation. Young, healthy participants. |

| Yamaguchi, 2013 [36] | Japan | Cross-sectional | 1368 | General population, M/F | 35–69 | Good/poor based on answers | Questions on sleep onset/offset regularity for the previous year | 47-item FFQ | To evaluate the associations between dietary factors and sleep–wake regularity. | Lowest quartile of protein intake (<10.8% energy) was associated with poor sleep-wake regularity (OR = 2.1; 95% CI: 1.3–3.3). The highest quartile of carbohydrate intake (≥70.7% energy) was associated with poor sleep-wake regularity (OR = 2.1; 95% CI: 1.3–3.5). The lowest intake of the staple foods at breakfast and the highest intake at lunch and dinner were associated with poor sleep-wake regularity (OR = 2.5, 95% CI: 1.7–3.5 for breakfast, OR = 3.2, 95% CI: 1.4–7.2 and 2.5, 95% CI: 1.3–4.9 for lunch and dinner, respectively). | No power calculation. Sleep–wake regularity self-reported for the past year. |

| Association of day-to-day variability in sleep timing with meal timing | |||||||||||

| Linnaranta, 2020 [37] | Canada | Cross-sectional | 29 | Patients with eating disorders, F | 26 (9.75) | StDev of centre of daily inactivity | 14 days of actigraphy | 14 days of food diaries | To correlate eating patterns with sleep. | Variability in sleep timing was associated with meal timing variability (rho = 0.47, p = 0.010). | No power calculation. Patients with eating disorders. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rusu, A.; Ciobanu, D.M.; Inceu, G.; Craciun, A.-E.; Fodor, A.; Roman, G.; Bala, C.G. Variability in Sleep Timing and Dietary Intake: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5248. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245248

Rusu A, Ciobanu DM, Inceu G, Craciun A-E, Fodor A, Roman G, Bala CG. Variability in Sleep Timing and Dietary Intake: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Nutrients. 2022; 14(24):5248. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245248

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusu, Adriana, Dana Mihaela Ciobanu, Georgeta Inceu, Anca-Elena Craciun, Adriana Fodor, Gabriela Roman, and Cornelia Gabriela Bala. 2022. "Variability in Sleep Timing and Dietary Intake: A Scoping Review of the Literature" Nutrients 14, no. 24: 5248. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245248

APA StyleRusu, A., Ciobanu, D. M., Inceu, G., Craciun, A.-E., Fodor, A., Roman, G., & Bala, C. G. (2022). Variability in Sleep Timing and Dietary Intake: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Nutrients, 14(24), 5248. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245248