Animal- and Plant-Based Protein Sources: A Scoping Review of Human Health Outcomes and Environmental Impact

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Dietary Protein Quality

3.1. Traditional Approach to Protein Quality Evaluation

- the specific amino acid composition (the intrinsic quality of proteins);

- digestibility (the extrinsic quality of proteins) [13].

- the digestion of proteins and the absorption of the constituent amino acids (so-called digestibility) [9]. «Digestibility is defined as the difference between the amount of N ingested and excreted, expressed as a proportion of N ingested». Due to the processes of protein metabolization of the intestinal microbiota, it is more appropriate to consider ileal digestibility than the fecal digestibility [15]. More precisely, it is necessary to measure the true ileal digestibility (TID), which also takes into account the endogenous protein losses (both basal and specific ones) [15].

- The utilization of the absorbed amino acids to support whole-body protein synthesis (so-called availability).

3.2. Recent Approaches to Protein Quality Evaluation

4. Dietary Patterns and Protein Intake

4.1. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns

4.1.1. Health Outcomes

- “semi-vegetarian diet” or “low-occasional meat-eaters” (flexitarian);

- “pesco-vegetarian diet” or “fish-eaters” (pescatarian);

- “lacto-ovo vegetarian diet” or more generically “vegetarians”;

- “vegan diet” or “vegans”.

Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases

Cancers

4.1.2. Environmental Impact

4.2. Mediterranean Diet

4.2.1. Health Outcomes

4.2.2. Environmental Impact

5. Health Outcomes and Environmental Impact of Protein Sources

5.1. Animal Protein Sources

5.1.1. Meat

5.1.2. Fish

5.1.3. Eggs

5.1.4. Dairy Products

5.2. Plant-Based Protein Sources

5.2.1. Legumes

5.2.2. Nuts and Seeds

5.2.3. Cereal Grains

5.3. Protein Sources Comparison

5.3.1. Health Outcomes

Mortality

Incidence

5.3.2. Environmental Impact

| Environmental Footprints | Units of Measurement | Red Meat | Poultry | FISH | EGGS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon footprint | kg CO2-eq/kg (food) | 25.58/26.61 [212] a 5.77 [212] b | 3.65 [212] | 3.49 [212] | 3.46 [212] | |

| Water footprint (total) | m3/ton (food) | 8761/15415 [213] a 5988 [213] b | 4325 [213] | 1974 [214] | 3265 [213] | |

| Land footprint | m2/kg (food) | 308.58/542.82 [215] a 19.53 [215] b | 19.22 [215] | 0–10 [216] | 17.83 [215] | |

| CED e | MJ/kg (food) | 37–82 [217] a 25–31 [217] b | 18–33 [217] | No data | 12–17 [217] | |

| Use of chemicals | Fertilizers (N footprint and P footprint) | 10 g N/serving | 30.01/30.27 [6] a 56.68 [6] b | 55.22 [6] | 18.46 [6] | 25.61 [6] |

| 10 g P/serving | 5.43/5.89 [6] a 9.75 [6] b | 9.92 [6] | 3.98 [6] | 4.40 [6] | ||

| Pesticides | / | No data | No data | No data | No data | |

| Biodiversity footprint | / f | VERY HIGH [218] | VERY HIGH [218] | VERY HIGH [110] | HIGH [110] | |

| Environmental footprints | Units of measurement | Dairy products | Legumes | Nuts | Cereal grains | |

| Carbon footprint | kg CO2-eq/kg (food) | 8.55/9.25 [212] c. 1.29 [212] d/2.59 [219] d | 1.20 [212] | 0.51 [212] | 0.50 [212] | |

| Water footprint (total) | m3/ton (food) | 5553/6760 [213] c 1020 [213] d/1485 [219] d | 9063 [213] | 4055 [213] | 1644 [213] | |

| Land footprint | m2/kg (food) | 60.27/65.20 [215] c 9.09 [215] d/12 [219] d | 6.96 [215] | 11.19 [215] | 2.81 [215] | |

| CED e | MJ/kg (food) | 38 [217] c 3.0–3.1 [217] d | 2.9–7.4 [217] | No data | 1.7–9.6 [217] | |

| Use of chemicals | Fertilizers (N footprint and P footprint) | 10 g N/serving | 15.18 [6] | 0 [6] | 4.28 [6] | No data |

| 10 g P/serving | 3.79 [6] | 0 [6] | 0.63 [6] | No data | ||

| Pesticides | / | No data | No data | No data | No data | |

| Biodiversity footprint | / f | high [110] | low [110] | high [110] | intermediate [220] g | |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moughan, P.J. Dietary Protein for Human Health. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan-Mihan, A.; Luhovyy, B.L.; El Khoury, D.; Anderson, G.H. Dietary Proteins as Determinants of Metabolic and Physiologic Functions of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Nutrients 2011, 3, 574–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.M.; Chevalier, S.; Leidy, H.J. Protein “Requirements” beyond the RDA: Implications for Optimizing Health. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlüter, O.; Rumpold, B.; Holzhauser, T.; Roth, A.; Vogel, R.F.; Quasigroch, W.; Vogel, S.; Heinz, V.; Jäger, H.; Bandick, N.; et al. Safety Aspects of the Production of Foods and Food Ingredients from Insects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CREA Italia. Tabelle Di Composizione Degli Alimenti—Ricerca per Nutriente (% Proteine per 100g Di Prodotto). Available online: https://www.alimentinutrizione.it/tabelle-nutrizionali/ricerca-per-nutriente (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Dias, B.F.S.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROCODE 2 Food Coding System—Main Food Groups: Classification, Categories and Policies, Version 99/2. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20200116170731/http://www.ianunwin.demon.co.uk/eurocode/docmn/ec99/ecmgintr.htm#MGList (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Kashyap, S.; Calvez, J.; Devi, S.; Azzout-Marniche, D.; Tomé, D.; Kurpad, A.V.; Gaudichon, C. Evaluation of Protein Quality in Humans and Insights on Stable Isotope Approaches to Measure Digestibility—A Review. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.L.; Doughty, K.N.; Geagan, K.; Jenkins, D.A.; Gardner, C.D. Perspective: The Public Health Case for Modernizing the Definition of Protein Quality. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint WHO/FAO/UNU Expert Consultation. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; pp. 1–265. [Google Scholar]

- Millward, D.J.; Layman, D.K.; Tomé, D.; Schaafsma, G. Protein Quality Assessment: Impact of Expanding Understanding of Protein and Amino Acid Needs for Optimal Health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1576S–1581S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids, 2nd ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780309085250. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, S.; Schop, M.; de Boer, I.J.M.; Huppertz, T. Protein Quality in Perspective: A Review of Protein Quality Metrics and Their Applications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, A.J.; Hodgkinson, S.M. Quantifying the Digestibility of Dietary Protein. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1850S–1856S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO/WHO. Protein Quality Evaluation: Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation, Bethesda, MD, USA, 4–8 December 1989; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1991; ISBN 9789251030974. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, R.R.; Rutherfurd, S.M.; Kim, I.-Y.; Moughan, P.J. Protein Quality as Determined by the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score: Evaluation of Factors Underlying the Calculation. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 584–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. Dietary Protein Quality Evaluation in Human Nutrition: Report of an FAO Expert Consultation, Auckland, New Zealand, 31 March–2 April 2011; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 9789251074176. [Google Scholar]

- Uauy, R. Keynote: Rethinking Protein. Food Nutr. Bull. 2013, 34, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinangeli, C.P.F.; House, J.D. Potential Impact of the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score as a Measure of Protein Quality on Dietary Regulations and Health. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewy, M.W.; Patel, A.; Abdelmagid, M.G.; Mohamed Elfadil, O.; Bonnes, S.L.; Salonen, B.R.; Hurt, R.T.; Mundi, M.S. Plant-Based Diet: Is It as Good as an Animal-Based Diet When It Comes to Protein? Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Dietary Supplements (NIH). Nutrient Recommendations and Databases. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/Dietary_Reference_Intakes.aspx (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Vanham, D.; Leip, A.; Galli, A.; Kastner, T.; Bruckner, M.; Uwizeye, A.; van Dijk, K.; Ercin, E.; Dalin, C.; Brandão, M.; et al. Environmental Footprint Family to Address Local to Planetary Sustainability and Deliver on the SDGs. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessari, P.; Lante, A.; Mosca, G. Essential Amino Acids: Master Regulators of Nutrition and Environmental Footprint? Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardy, A.; Johnston, C.S.; Plukis, A.; Vizcaino, M.; Wharton, C. Integrating Protein Quality and Quantity with Environmental Impacts in Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO/TC 207/SC 5) ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. Available online: https://www.iso.org/cms/render/live/en/sites/isoorg/contents/data/standard/03/74/37456.html (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Notarnicola, B.; Sala, S.; Anton, A.; McLaren, S.J.; Saouter, E.; Sonesson, U. The Role of Life Cycle Assessment in Supporting Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: A Review of the Challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedy, J.; Wirfält, E.; Flood, A.; Mitrou, P.N.; Krebs-Smith, S.M.; Kipnis, V.; Midthune, D.; Leitzmann, M.; Hollenbeck, A.; Schatzkin, A.; et al. Comparing 3 Dietary Pattern Methods—Cluster Analysis, Factor Analysis, and Index Analysis—With Colorectal Cancer Risk. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 171, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnoli, C.; Baroni, L.; Bertini, I.; Ciappellano, S.; Fabbri, A.; Papa, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Sbarbati, R.; Scarino, M.L.; Siani, V.; et al. Position Paper on Vegetarian Diets from the Working Group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlich, M.J.; Singh, P.N.; Sabaté, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Knutsen, S.; Beeson, W.L.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns and Mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Nutrient Profiles of Vegetarian and Non-Vegetarian Dietary Patterns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlich, M.J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabaté, J.; Fan, J.; Singh, P.N.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of Food Consumption among Vegetarians and Non-Vegetarians. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papier, K.; Tong, T.Y.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Fensom, G.K.; Knuppel, A.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Comparison of Major Protein-Source Foods and Other Food Groups in Meat-Eaters and Non-Meat-Eaters in the EPIC-Oxford Cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.A. A Vegetarian-Style Dietary Pattern Is Associated with Lower Energy, Saturated Fat, and Sodium Intakes; and Higher Whole Grains, Legumes, Nuts, and Soy Intakes by Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2013–2016. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visioli, F.; Borsani, L.; Galli, C. Diet and Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease: The Potential Role of Phytochemicals. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 47, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, J. Opening Statement for Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids 1st Ed. 2002. Available online: http://www8.nationalacademies.org/onpinews/newsitem.aspx?RecordID=s10490 (accessed on 7 May 2022).

- Mariotti, F.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, P.N.; Key, T.J. The Long-Term Health of Vegetarians and Vegans. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Vegetarian, Vegan Diets and Multiple Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3640–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Yang, B.; Zheng, J.; Li, G.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Li, D. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality and Cancer Incidence in Vegetarians: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 60, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Park, K. Adherence to a Vegetarian Diet and Diabetes Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oussalah, A.; Levy, J.; Berthezène, C.; Alpers, D.H.; Guéant, J.-L. Health Outcomes Associated with Vegetarian Diets: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 3283–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zheng, J.; Yang, B.; Jiang, J.; Fu, Y.; Li, D. Effects of Vegetarian Diets on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. Cardiovasc. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2015, 4, e002408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Nishimura, K.; Barnard, N.D.; Takegami, M.; Watanabe, M.; Sekikawa, A.; Okamura, T.; Miyamoto, Y. Vegetarian Diets and Blood Pressure: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Levin, S.M.; Barnard, N.D. Association between Plant-Based Diets and Plasma Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. Scientific Report of the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Tantamango-Bartley, Y.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fan, J.; Fraser, G. Vegetarian Diets and the Incidence of Cancer in a Low-Risk Population. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2013, 22, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlich, M.J.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Diets in the Adventist Health Study 2: A Review of Initial Published Findings1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 353S–358S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, B.J.; Anousheh, R.; Fan, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Diets and Blood Pressure among White Subjects: Results from the Adventist Health Study-2 (AHS-2). Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1909–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, G.; Katuli, S.; Anousheh, R.; Knutsen, S.; Herring, P.; Fan, J. Vegetarian Diets and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Black Members of the Adventist Health Study-2. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonstad, S.; Butler, T.; Yan, R.; Fraser, G.E. Type of Vegetarian Diet, Body Weight, and Prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonstad, S.; Stewart, K.; Oda, K.; Batech, M.; Herring, R.P.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Diets and Incidence of Diabetes in the Adventist Health Study-2. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Sabaté, J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Fraser, G.E. Vegetarian Dietary Patterns Are Associated with a Lower Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: The Adventist Health Study 2. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia-Siapco, G.; Sabaté, J. Health and Sustainability Outcomes of Vegetarian Dietary Patterns: A Revisit of the EPIC-Oxford and the Adventist Health Study-2 Cohorts. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 72, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Spencer, E.A.; Travis, R.C.; Roddam, A.W.; Allen, N.E. Mortality in British Vegetarians: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1613S–1619S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Spencer, E.A.; Travis, R.C.; Roddam, A.W.; Allen, N.E. Cancer Incidence in Vegetarians: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1620S–1626S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, F.L.; Appleby, P.N.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Risk of Hospitalization or Death from Ischemic Heart Disease among British Vegetarians and Nonvegetarians: Results from the EPIC-Oxford Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobiecki, J.G.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Key, T.J. High Compliance with Dietary Recommendations in a Cohort of Meat Eaters, Fish Eaters, Vegetarians, and Vegans: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition–Oxford Study. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, K.E.; Crowe, F.L.; Appleby, P.N.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Serum Concentrations of Cholesterol, Apolipoprotein A-I and Apolipoprotein B in a Total of 1694 Meat-Eaters, Fish-Eaters, Vegetarians and Vegans. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, E.A.; Appleby, P.N.; Davey, G.K.; Key, T.J. Diet and Body Mass Index in 38 000 EPIC-Oxford Meat-Eaters, Fish-Eaters, Vegetarians and Vegans. Int. J. Obes. 2003, 27, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Crowe, F.L.; Bradbury, K.E.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C. Cancer in British Vegetarians: Updated Analyses of 4998 Incident Cancers in a Cohort of 32,491 Meat Eaters, 8612 Fish Eaters, 18,298 Vegetarians, and 2246 Vegans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 378S–385S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key, T.J.; Fraser, G.E.; Thorogood, M.; Appleby, P.N.; Beral, V.; Reeves, G.; Burr, M.L.; Chang-Claude, J.; Frentzel-Beyme, R.; Kuzma, J.W.; et al. Mortality in Vegetarians and Nonvegetarians: Detailed Findings from a Collaborative Analysis of 5 Prospective Studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 516s–524s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleby, P.N.; Crowe, F.L.; Bradbury, K.E.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Mortality in Vegetarians and Comparable Nonvegetarians in the United Kingdom. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, P.; Tucker, K.L.; Wolk, A. Risk of Overweight and Obesity among Semivegetarian, Lactovegetarian, and Vegan Women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Rebholz, C.M. Healthy Plant-Based Diets Are Associated with Lower Risk of All-Cause Mortality in US Adults. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, L.E.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Steffen, L.M.; Coresh, J.; Rebholz, C.M. Plant-Based Diets Are Associated with a Lower Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality in a General Population of Middle-Aged Adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e012865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Anderson, R.M. Nutrition, Longevity and Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Interventions. Cell 2022, 185, 1455–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global Diets Link Environmental Sustainability and Human Health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. The Diet, Health, and Environment Trilemma. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change and Land—An IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems; Shukla, P.R., Skea, J., Calvo Buendia, E., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Zhai, P., Slade, R., Connors, S., van Diemen, R., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McMichael, A.J.; Powles, J.W.; Butler, C.D.; Uauy, R. Food, Livestock Production, Energy, Climate Change, and Health. Lancet 2007, 370, 1253–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinfeld, H.; Gerber, P.; Wassenaar, T.; Castel, V.; Rosales, M.; de Haan, C. Livestock’s Long Shadow; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; ISBN 9789251055717. [Google Scholar]

- Springmann, M.; Clark, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Wiebe, K.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Lassaletta, L.; de Vries, W.; Vermeulen, S.J.; Herrero, M.; Carlson, K.M.; et al. Options for Keeping the Food System within Environmental Limits. Nature 2018, 562, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T.B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and Nutritional Aspects of Sustainable Diet Strategies and Their Association with Environmental Impacts: A Global Modelling Analysis with Country-Level Detail. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroni, L.; Cenci, L.; Tettamanti, M.; Berati, M. Evaluating the Environmental Impact of Various Dietary Patterns Combined with Different Food Production Systems. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresán, U.; Sabaté, J. Vegetarian Diets: Planetary Health and Its Alignment with Human Health. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S380–S388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soret, S.; Mejia, A.; Batech, M.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Harwatt, H.; Sabaté, J. Climate Change Mitigation and Health Effects of Varied Dietary Patterns in Real-Life Settings throughout North America. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 490S–495S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, P.; Appleby, P.N.; Mizdrak, A.; Briggs, A.D.M.; Travis, R.C.; Bradbury, K.E.; Key, T.J. Dietary Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Meat-Eaters, Fish-Eaters, Vegetarians and Vegans in the UK. Clim. Change 2014, 125, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, J.; Soret, S. Sustainability of Plant-Based Diets: Back to the Future. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 476S–482S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, A.; Mena, P.; Pellegrini, N.; Turroni, S.; Neviani, E.; Ferrocino, I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ruini, L.; Ciati, R.; Angelino, D.; et al. Environmental Impact of Omnivorous, Ovo-Lacto-Vegetarian, and Vegan Diet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Macchi, C.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Mediterranean Diet and Health Status: An Updated Meta-Analysis and a Proposal for a Literature-Based Adherence Score. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2769–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S.; Jayedi, A.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Becerra-Tomás, N.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Relation to All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 1029–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Blanco Mejía, S.; Viguiliouk, E.; Khan, T.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Kahleova, H.; Rahelić, D.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Mediterranean Diet, Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies and Randomized Clinical Trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 1207–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jannasch, F.; Kröger, J.; Schulze, M.B. Dietary Patterns and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Zappalà, G.; Bernardini, S.; Giambini, I.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Inversely Associated with Metabolic Syndrome Occurrence: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 68, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean Diet and Health: A Comprehensive Overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, F.; Abbate, R.; Gensini, G.F.; Casini, A. Accruing Evidence on Benefits of Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet on Health: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morze, J.; Danielewicz, A.; Przybyłowicz, K.; Zeng, H.; Hoffmann, G.; Schwingshackl, L. An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Cancer. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1561–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, A.; Costacou, T.; Bamia, C.; Trichopoulos, D. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet and Survival in a Greek Population. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2599–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.E.; Hamm, M.W.; Hu, F.B.; Abrams, S.A.; Griffin, T.S. Alignment of Healthy Dietary Patterns and Environmental Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1005–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 26th FAO Regional Conference for Europe; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S. Sustainable Diets: The Mediterranean Diet as an Example. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2285–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carni Sostenibili. Clessidra Ambientale. Available online: https://www.carnisostenibili.it/clessidra-ambientale/ (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Coop Italia. La Sostenibilità delle Carni Bovine a Marchio Coop—Gli impatti Economici, Sociali ed Ambientali della Filiera delle Carni; Carni Sostenibili: Coop, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CREA-NUT (ex INRAN). Linee Guida per una sana Alimentazione. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/web/alimenti-e-nutrizione/-/linee-guida-1 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Ulaszewska, M.M.; Luzzani, G.; Pignatelli, S.; Capri, E. Assessment of Diet-Related GHG Emissions Using the Environmental Hourglass Approach for the Mediterranean and New Nordic Diets. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Bodereau, V.; van der Kamp, M.; Clegg, M.; Guo, J.; del Castillo, M.D.; Gilcrease, W.; Hollywood, A.; Iriondo-DeHond, A.; Mills, C.; et al. Educating Health Care Professionals on the Importance of Proper Diets. An Online Course on Nutrition, Health, and Sustainability. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fresán, U.; Martínez-Gonzalez, M.-A.; Sabaté, J.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. The Mediterranean Diet, an Environmentally Friendly Option: Evidence from the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) Cohort. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

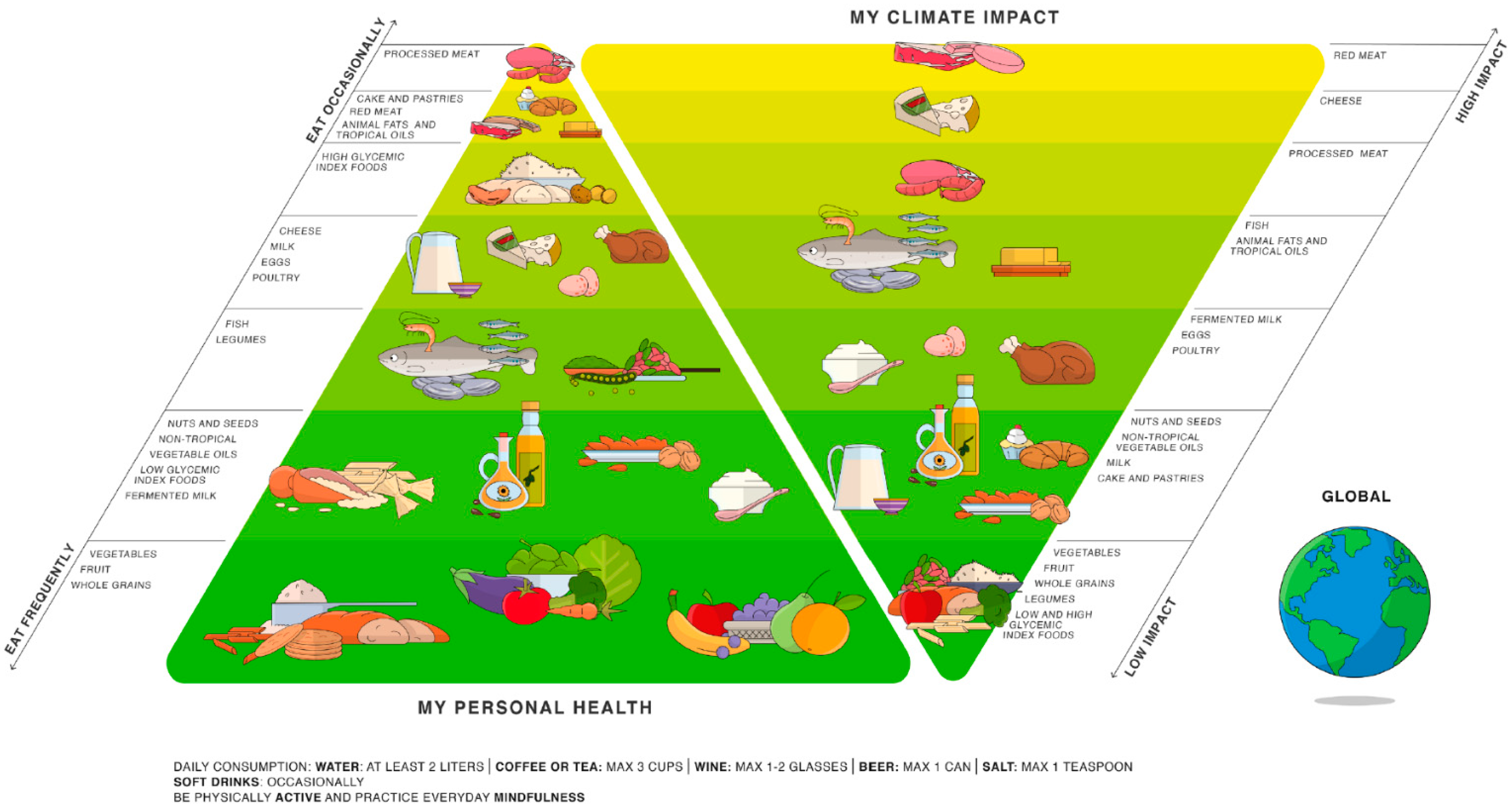

- Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition (BCFN) Foundation. Doppia Piramide Alimentare. Available online: https://www.fondazionebarilla.com/doppia-piramide/ (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Burlingame, B.; Dernini, S.; FAO; Nutrition and Consumer Protection Division. Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity—Directions and Solutions for Policy, Research and Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 280–293. ISBN 9789251072882. [Google Scholar]

- Ruini, L.; Ciati, R.; Pratesi, C.A.; Marino, M.; Principato, L.; Vannuzzi, E. Working toward Healthy and Sustainable Diets: The “Double Pyramid Model” Developed by the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition to Raise Awareness about the Environmental and Nutritional Impact of Foods. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.R.; Tapsell, L.C. Food, Not Nutrients, Is the Fundamental Unit in Nutrition. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsell, L.C.; Neale, E.P.; Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Foods, Nutrients, and Dietary Patterns: Interconnections and Implications for Dietary Guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M. Global Nutrition Dynamics: The World Is Shifting Rapidly toward a Diet Linked with Noncommunicable Diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, V. An Analysis of the Relationship between Income and Proteins Consumption. Master’s degree, University of Turin, Torino, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Krams, I.; Luoto, S.; Rubika, A.; Krama, T.; Elferts, D.; Krams, R.; Kecko, S.; Skrinda, I.; Moore, F.R.; Rantala, M.J. A Head Start for Life History Development? Family Income Mediates Associations between Height and Immune Response in Men. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2019, 168, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD. 2017 Diet Collaborators, Health Effects of Dietary Risks in 195 Countries, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Care Without Harm. Redefining Protein: Adjusting Diets to Protect Public Health and Conserve Resources; Health Care Without Harm: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe, G.A.; Takahashi, T.; Lee, M.R.F. Applications of Nutritional Functional Units in Commodity-Level Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Agri-Food Systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Vogelstein, B. Stem Cell Divisions, Somatic Mutations, Cancer Etiology, and Cancer Prevention. Science 2017, 355, 1330–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Ouyang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Pan, A.; Hu, F.B. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Mortality: Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Lampousi, A.-M.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food Groups and Risk of All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.; Springmann, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. Multiple Health and Environmental Impacts of Foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23357–23362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeraatkar, D.; Han, M.A.; Guyatt, G.H.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; El Dib, R.; Cheung, K.; Milio, K.; Zworth, M.; Bartoszko, J.J.; Valli, C.; et al. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk for All-Cause Mortality and Cardiometabolic Outcomes. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abete, I.; Romaguera, D.; Vieira, A.R.; de Munain, A.L.; Norat, T. Association between Total, Processed, Red and White Meat Consumption and All-Cause, CVD and IHD Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechthold, A.; Boeing, H.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; De Henauw, S.; Michels, N.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Schlesinger, S.; et al. Food Groups and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke and Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1071–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Hyeon, J.; Lee, S.A.; Kwon, S.O.; Lee, H.; Keum, N.; Lee, J.-K.; Park, S.M. Role of Total, Red, Processed, and White Meat Consumption in Stroke Incidence and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Andriolo, V.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food Groups and Risk of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, R.; Han, T.; Sun, C.; Na, L. Dietary Protein Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuenschwander, M.; Ballon, A.; Weber, K.S.; Norat, T.; Aune, D.; Schwingshackl, L.; Schlesinger, S. Role of Diet in Type 2 Diabetes Incidence: Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses of Prospective Observational Studies. BMJ 2019, 366, l2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlesinger, S.; Neuenschwander, M.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Bechthold, A.; Boeing, H.; Schwingshackl, L. Food Groups and Risk of Overweight, Obesity, and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Laure Preterre, A.; Iqbal, K.; Bechthold, A.; De Henauw, S.; Michels, N.; Devleesschauwer, B.; et al. Food Groups and Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, A.R.; Abar, L.; Chan, D.S.M.; Vingeliene, S.; Polemiti, E.; Stevens, C.; Greenwood, D.; Norat, T. Foods and Beverages and Colorectal Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies, an Update of the Evidence of the WCRF-AICR Continuous Update Project. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1788–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farvid, M.S.; Stern, M.C.; Norat, T.; Sasazuki, S.; Vineis, P.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Wolk, A.; Wu, K.; Stewart, B.W.; Cho, E. Consumption of Red and Processed Meat and Breast Cancer Incidence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2787–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, R.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Ho, J.C.-M.; Zheng, Y. Dietary Protein Sources and Incidence of Breast Cancer: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2016, 8, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Wei, J.; He, X.; An, P.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Shao, D.; Liang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; et al. Landscape of Dietary Factors Associated with Risk of Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 2820–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.R.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.A.; Kwon, S.O.; Lee, J.-K.; Keum, N.; Park, S.M. Effect of Red, Processed, and White Meat Consumption on the Risk of Gastric Cancer: An Overall and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Appel, L.J.; Van Horn, L. Components of a Cardioprotective Diet. Circulation 2011, 123, 2870–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mente, A.; de Koning, L.; Shannon, H.S.; Anand, S.S. A Systematic Review of the Evidence Supporting a Causal Link Between Dietary Factors and Coronary Heart Disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAfee, A.J.; McSorley, E.M.; Cuskelly, G.J.; Moss, B.W.; Wallace, J.M.W.; Bonham, M.P.; Fearon, A.M. Red Meat Consumption: An Overview of the Risks and Benefits. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; La Vignera, S.; Condorelli, R.A.; Godos, J.; Marventano, S.; Tieri, M.; Ghelfi, F.; Titta, L.; Lafranconi, A.; Gambera, A.; et al. Total, Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Human Health: An Umbrella Review of Observational Studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Ursin, G.; Veierød, M.B. Meat Consumption and the Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feskens, E.J.M.; Sluik, D.; van Woudenbergh, G.J. Meat Consumption, Diabetes, and Its Complications. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2013, 13, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micha, R.; Wallace, S.K.; Mozaffarian, D. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2010, 121, 2271–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, A.; Sun, Q.; Bernstein, A.M.; Schulze, M.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Red Meat Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: 3 Cohorts of US Adults and an Updated Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Keogh, J.; Clifton, P. A Review of Potential Metabolic Etiologies of the Observed Association between Red Meat Consumption and Development of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Metabolism 2015, 64, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellou, V.; Belbasis, L.; Tzoulaki, I.; Evangelou, E. Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Exposure-Wide Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.-G.; Sun, J.-W.; Yang, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Xiang, Y.-B. Fish Consumption and All-Cause Mortality: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xiong, K.; Cai, J.; Ma, A. Fish Consumption and Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Tang, H.; Yang, X.; Luo, X.; Wang, X.; Shao, C.; He, J. Fish Consumption and Stroke Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Orsini, N. Fish Consumption and the Risk of Stroke. Stroke 2011, 42, 3621–3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, G.; Heidari, Z.; Firouzi, S.; Haghighatdoost, F. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Fish Consumption and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Feng, B.; Li, K.; Zhu, X.; Liang, S.; Liu, X.; Han, S.; Wang, B.; Wu, K.; Miao, D.; et al. Fish Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Med. 2012, 125, 551–559.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-S.; Hu, X.-J.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Yang, J.; Li, D. Intake of Fish and Marine N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Risk of Breast Cancer: Meta-Analysis of Data from 21 Independent Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ 2013, 346, f3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.-Z.; Xu, J.-Y.; Chen, G.-C.; Ma, Y.-X.; Qin, L.-Q. Effects of Fatty and Lean Fish Intake on Stroke Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Poli, A. Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Risk. Evidence, Lack of Evidence, and Diligence. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visioli, F.; Agostoni, C. Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Health: The Little We Know after All These Years. Nutrients 2022, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adkins, Y.; Kelley, D.S. Mechanisms Underlying the Cardioprotective Effects of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2010, 21, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wu, J.H.Y. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2047–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micallef, M.; Munro, I.; Phang, M.; Garg, M. Plasma N-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Are Negatively Associated with Obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 1370–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, N.; Portmann, M.; Heg, Z.; Hofmann, K.; Zwahlen, M.; Egger, M. Fish or N3-PUFA Intake and Body Composition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 657–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaset, B.; Øyen, J.; Jacques, H.; Kristiansen, K.; Madsen, L. Seafood Intake and the Development of Obesity, Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2019, 32, 146–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Rimm, E.B. Fish Intake, Contaminants, and Human HealthEvaluating the Risks and the Benefits. JAMA 2006, 296, 1885–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpala, C.O.R.; Sardo, G.; Vitale, S.; Bono, G.; Arukwe, A. Hazardous Properties and Toxicological Update of Mercury: From Fish Food to Human Health Safety Perspective. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1986–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de las Hazas, M.-C.; Boughanem, H.; Dávalos, A. Untoward Effects of Micro- and Nanoplastics: An Expert Review of Their Biological Impact and Epigenetic Effects. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.C.; O’Neill, B.; Sigge, G.O.; Kerwath, S.E.; Hoffman, L.C. Heavy Metals in Marine Fish Meat and Consumer Health: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Lavie, C.J.; Harris, W.S. Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Cardiovascular Benefits, Sources and Sustainability. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2009, 6, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavina, M.; Battino, M.; Gaddi, A.V.; Savo, M.T.; Visioli, F. Supplementation with Alpha-Linolenic Acid and Inflammation: A Feasibility Trial. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M.; Galli, C.; Visioli, F.; Renaud, S.; Simopoulos, A.P.; Spector, A.A. Role of Plant-Derived Omega–3 Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2000, 44, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro, I.; Lupon, J.; Cediel, G.; Codina, P.; Fito, M.; Domingo, M.; Santiago-Vacas, E.; Zamora, E.; Sala-Vila, A.; Bayes-Genís, A. Relationship of Circulating Vegetable Omega-3 to Prognosis in Patients with Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Micek, A.; Brzostek, T.; Toledo, E.; Iacoviello, L.; Astrup, A.; Franco, O.H.; Galvano, F.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Grosso, G. Egg Consumption and Cardiovascular Risk: A Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1833–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhu, T.; Song, Y.; Yu, M.; Shan, Z.; Sands, A.; Hu, F.B.; Liu, L. Egg Consumption and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ 2013, 346, e8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G.; Lampousi, A.-M.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Schwedhelm, C.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food Groups and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, S.; Raman, G.; Vishwanathan, R.; Jacques, P.F.; Johnson, E.J. Dietary Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, J. Dairy Food Consumption Is Associated with a Lower Risk of the Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghshi, S.; Sadeghi, O.; Larijani, B.; Esmaillzadeh, A. High vs. Low-Fat Dairy and Milk Differently Affects the Risk of All-Cause, CVD, and Cancer Death: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3598–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Shen, M.; Du, S.; Chen, T.; Zou, S. The Association between Dairy Intake and Breast Cancer in Western and Asian Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Breast Cancer 2015, 18, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sun, D. Consumption of Yogurt and the Incident Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Nine Cohort Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI): The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; Otten, J.J., Hellwig, J.P., Meyers, L.D., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780309157421. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, S.A. Defining the Process of Dietary Reference Intakes: Framework for the United States and Canada. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 94, 655S–657S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshavarz, R.; Didinger, C.; Duncan, A.; Thompson, H. Pulse Crops and Their Key Role as Staple Foods in Healthful Eating Patterns; Crop Series Production; Colorado State University: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer, C.H.; Lam, H.-M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Varshney, R.K.; Colmer, T.D.; Cowling, W.; Bramley, H.; Mori, T.A.; Hodgson, J.M.; et al. Neglecting Legumes Has Compromised Human Health and Sustainable Food Production. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerra-Tomás, N.; Papandreou, C.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Legume Consumption and Cardiometabolic Health. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S437–S450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshin, A.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Mozaffarian, D. Consumption of Nuts and Legumes and Risk of Incident Ischemic Heart Disease, Stroke, and Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis1234. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Jiao, S.; Dong, W. Association between Consumption of Soy and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Jiang, H.; Shi, J.; Shi, X.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J.; Kong, L.; Zhang, W.; et al. Intake of Soy, Soy Isoflavones and Soy Protein and Risk of Cancer Incidence and Mortality. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 847421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-Y.; Qin, L.-Q. Soy Isoflavones Consumption and Risk of Breast Cancer Incidence or Recurrence: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 125, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryj, A.N.; Yu, N.; Aukema, H.M. Nutritional and Health Benefits of Pulses. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. Physiol. Appl. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 39, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W.; Major, A.W. Pulses and Lipaemia, Short- and Long-Term Effect: Potential in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Br. J. Nutr. 2002, 88, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguiliouk, E.; Glenn, A.J.; Nishi, S.K.; Chiavaroli, L.; Seider, M.; Khan, T.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Mejia, S.B.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; et al. Associations between Dietary Pulses Alone or with Other Legumes and Cardiometabolic Disease Outcomes: An Umbrella Review and Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, S308–S319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viguiliouk, E.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Can Pulses Play a Role in Improving Cardiometabolic Health? Evidence from Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, H.; Vasconcelos, M.; Gil, A.M.; Pinto, E. Benefits of Pulse Consumption on Metabolism and Health: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharrey, M.; Mariotti, F.; Mashchak, A.; Barbillon, P.; Delattre, M.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of Plant and Animal Protein Intake Are Strongly Associated with Cardiovascular Mortality: The Adventist Health Study-2 Cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 47, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosso, G.; Godos, J.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.; Ray, S.; Micek, A.; Pajak, A.; Sciacca, S.; D’Orazio, N.; Del Rio, D.; Galvano, F. A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis on Dietary Flavonoid and Lignan Intake and Cancer Risk: Level of Evidence and Limitations. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, G.; Fritz, H.; Balneaves, L.G.; Verma, S.; Skidmore, B.; Fernandes, R.; Kennedy, D.; Cooley, K.; Wong, R.; Sagar, S.; et al. Flax and Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, K.; Zaineddin, A.K.; Vrieling, A.; Linseisen, J.; Chang-Claude, J. Meta-Analyses of Lignans and Enterolignans in Relation to Breast Cancer Risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, S.K.; Viguiliouk, E.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Bazinet, R.P.; Hanley, A.J.; Comelli, E.M.; Salas Salvadó, J.; Jenkins, D.J.A.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Are Fatty Nuts a Weighty Concern? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis and Dose–Response Meta-Regression of Prospective Cohorts and Randomized Controlled Trials. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Ros, E. Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Insights from the PREDIMED Study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 58, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Sabaté, J.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Alonso, A.; Martínez, J.A.; Martínez-González, M.A. Nut Consumption and Weight Gain in a Mediterranean Cohort: The SUN Study. Obesity 2007, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mateo, G.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Basora, J.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Nut Intake and Adiposity: Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of Dietary Supplements (NIH). Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Omega3FattyAcids-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Scrinis, G. On the Ideology of Nutritionism. Gastronomica 2008, 8, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Chan, D.S.M.; Lau, R.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Dietary Fibre, Whole Grains, and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. BMJ 2011, 343, d6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant Proteins: Assessing Their Nutritional Quality and Effects on Health and Physical Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, W.W. Animal-Based and Plant-Based Protein-Rich Foods and Cardiovascular Health: A Complex Conundrum. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Fung, T.T.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Longo, V.D.; Chan, A.T.; Giovannucci, E.L. Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake with All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghshi, S.; Sadeghi, O.; Willett, W.C.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Dietary Intake of Total, Animal, and Plant Proteins and Risk of All Cause, Cardiovascular, and Cancer Mortality: Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ 2020, 370, m2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Li, Y.; Tobias, D.K.; Pan, A.; Hu, F.B. Dietary Protein Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.; Jayedi, A.; Jalilpiran, Y.; Hajishafiee, M.; Aminianfar, A.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Dietary Intake of Total, Animal and Plant Proteins and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease and Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, L.E.; Kushi, L.H.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Cerhan, J.R. Associations of Dietary Protein with Disease and Mortality in a Prospective Study of Postmenopausal Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Tangney, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Sacks, F.M.; Bennett, D.A.; Aggarwal, N.T. MIND Diet Associated with Reduced Incidence of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015, 11, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talegawkar, S.A.; Jin, Y.; Simonsick, E.M.; Tucker, K.L.; Ferrucci, L.; Tanaka, T. The Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) Diet Is Associated with Physical Function and Grip Strength in Older Men and Women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberger-Gateau, P.; Letenneur, L.; Deschamps, V.; Pérès, K.; Dartigues, J.-F.; Renaud, S. Fish, Meat, and Risk of Dementia: Cohort Study. BMJ 2002, 325, 932–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarmeas, N.; Anastasiou, C.A.; Yannakoulia, M. Nutrition and Prevention of Cognitive Impairment. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.; Springmann, M.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D.; Macdiarmid, J.I.; Fanzo, J.; Bandy, L.; Harrington, R.A. Estimating the Environmental Impacts of 57,000 Food Products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120584119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture 2021—Systems at Breaking Point: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022; ISBN 9789251361276. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, C.J. Plant-Based Animal Product Alternatives Are Healthier and More Environmentally Sustainable than Animal Products. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minotti, B.; Antonelli, M.; Dembska, K.; Marino, D.; Riccardi, G.; Vitale, M.; Calabrese, I.; Recanati, F.; Giosuè, A. True Cost Accounting of a Healthy and Sustainable Diet in Italy. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clune, S.; Crossin, E.; Verghese, K. Systematic Review of Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Different Fresh Food Categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. A Global Assessment of the Water Footprint of Farm Animal Products. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlow, M.; van Oel, P.R.; Mekonnen, M.M.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Increasing Pressure on Freshwater Resources Due to Terrestrial Feed Ingredients for Aquaculture Production. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 536, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.F.; Gephart, J.A.; Emery, K.A.; Leach, A.M.; Galloway, J.N.; D’Odorico, P. Meeting Future Food Demand with Current Agricultural Resources. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 39, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C.A.; Newton, R.; Bostock, J.; Prescott, S.; Honey, D.J.; Telfer, T.; Walmsley, S.F.; Little, D.C.; Hull, S.C. A Risk Benefit Analysis of Mariculture as a Means to Reduce the Impacts of Terrestrial Production of Food and Energy; Scottish Aquaculture Research Forum: Pitlochry, Scotland, 2015; ISBN 9781907266720. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.D.; Frostell, B.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A. Protein Efficiency per Unit Energy and per Unit Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Potential Contribution of Diet Choices to Climate Change Mitigation. Food Policy 2011, 36, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machovina, B.; Feeley, K.J.; Ripple, W.J. Biodiversity Conservation: The Key Is Reducing Meat Consumption. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 536, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition (BCFN) Foundation. Doppia Piramide 2016—Un Futuro più Sostenibile Dipende da noi. Available online: https://www.fondazionebarilla.com/publications/doppia-piramide-2016-un-futuro-piu-sostenibile-dipende-da-noi/ (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- WWF. Living Planet Report 2020—Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Petersen, T., Eds.; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 9782940529995. [Google Scholar]

- Westhoek, H.; Lesschen, J.P.; Rood, T.; Wagner, S.; De Marco, A.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Leip, A.; van Grinsven, H.; Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O. Food Choices, Health and Environment: Effects of Cutting Europe’s Meat and Dairy Intake. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Environmental Impacts of Food Consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, J.; Sranacharoenpong, K.; Harwatt, H.; Wien, M.; Soret, S. The Environmental Cost of Protein Food Choices. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2067–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable Deaths and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years Caused by Infections with Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A Population-Level Modelling Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Year | Vegetarian Dietary Patterns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetarian (Total) | Flexitarian | Pescatarian | Lacto-Ovo Vegetarian | Vegan | ||

| [64] | 1999 | 0.95 (0.82–1.11) | 0.84 (0.77–0.90) | 0.82 (0.77–0.96) | 0.84 (0.74–0.96) | 1.00 (0.70–1.44) |

| [57] | 2009 | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | No data | 0.89 (0.75–1.05) | 1.03 (0.90–1.16) | |

| [42] | 2012 | 0.91 (0.66–1.16) | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| [32,50] | 2013/2014 | 0.88 (0.80–0.97) | 0.92 (0.75–1.13) | 0.81 (0.69–0.94) | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | 0.85 (0.73–1.01) |

| Health Outcomes | Unit of Intake | RR (95% C.I.) | N° of Prospective Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.92 (0.91–0.93) | 7 | [83] | |

| 0.90 (0.89–0.91) | 28 | [84] | ||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) | 21 | [85] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.91 (0.87–0.96) | 26 | ||

| Total CVDs incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 8 | |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.90 (0.87–0.92) a | 8 | [83] | |

| 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 12 | [85] | ||

| CHD mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.73 (0.59–0.89) | 6 | |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.94 (0.91–0.96) | 6 | ||

| CHD incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.73 (0.62–0.86) | 7 | |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) | 8 | ||

| Stroke mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.87 (0.80–0.96) | 4 | |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | / | 6 | ||

| Stroke incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.80 (0.71–0.90) | 5 | |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 10 | ||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.87 (0.82–0.93) | 6 | [86] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.73 (0.54–0.98) | 4 | [87] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| NDDs | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.74 (0.65–0.84) b | 12 | [88] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.87 (0.81–0.94) | 4 | [89] | |

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.87 (0.82–0.92) | 18 | [90] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| 2-Point Increase MDS | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) a | 8 | [83] | |

| CRC c | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.92 (0.87–0.99) | 10 | [90] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| Breast cancer c | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 12 | [90] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| Gastric cancer c | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.77 (0.64–0.92) d | 4 | [90] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| Respiratory tract cancers c | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.84 (0.76–0.94) d | 5 | [90] |

| 2-Point Increase MDS | No data | |||

| Health Outcomes | Unit of Intake | RR (95% C.I.) | N° of Prospective Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Meat | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 2 | [113] |

| 1.10 (1.00–1.22) | 12 | [114] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.10 (1.04–1.18) | 10 | ||

| 1.12 (1.05–1.21) | / | [115] | ||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.88 (0.77–1.01) a | 8 | [116] |

| 1.16 (1.03–1.32) | 5 | [117] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.15 (1.05–1.26) | 3 | ||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | / | [115] |

| 1.16 (1.08–1.24) | 3 | [118] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | 3 | ||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.16 (1.08–1.25) | 7 | |

| 1.11 (1.03–1.20) | 3 | [119] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.12 (1.06–1.17) | 7 / | [118] [115] | |

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.15 (1.02–1.28) | 7 | [120] |

| Dose-Response | 1.14 (1.02–1.28) | 7 | ||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | 5 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 4 | ||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.22 (1.10–1.36) | 13 | [121] |

| Dose-Response | 1.17 (1.08–1.26) | 14 | [122] | |

| 1.13 (1.03–1.23) | / | [115] | ||

| Overweight/obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.23 (1.07–1.41) | 1 | [123] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 2 | [113] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.12 (1.06–1.18) | 25 | [124] |

| Dose-Response | 1.12 (1.06–1.19) | 18 / | [124] [115] | |

| 1.12 (1.00–1.25) | 8 | [125] | ||

| BREAST CANCER | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.09 (0.99–1.21) | 7 | [126] |

| / | 8 | [127] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 6 | ||

| GASTRIC CANCER | Highest vs. Lowest | / / | 13 6 | [128] [129] |

| Dose-Response | / | 4 | [129] | |

| Processed Meat | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.21 (1.16–1.26) | 7 | [114] |

| Dose-Response | 1.23 (1.12–1.36) | 7 | ||

| 1.41 (1.21–1.67) | / | [115] | ||

| Total CVD mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.81 (0.75–0.87) | / | [116] |

| 1.18 (1.05–1.32) | 7 | [117] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.24 (1.09–1.40) | 6 | ||

| 1.15 (1.07–1.24) | 6 | [113] | ||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.15 (0.99–1.33) | 5 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | 1.27 (1.09–1.49) | 3 / | [118] [115] | |

| 1.42 (1.07–1.89) | 6 | [130] | ||

| STROKE | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.16 (1.07–1.26) | 6 | [118] |

| 1.17 (1.08–1.25) | 4 | [119] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.17 (1.02–1.34) | 6 / | [118] [115] | |

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 5 | [120] |

| Dose-Response | 1.12 (1.00–1.26) | 4 | ||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.27 (1.14–1.41) | 3 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | 1.12 (1.05–1.19) | 2 | ||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.39 (1.29–1.49) | 11 | [121] |

| Dose-Response | 1.32 (1.19–1.48) | / | [115] | |

| 1.37 (1.22–1.54) | 14 | [122] | ||

| 1.57 (1.28–1.93) | 8 | [130] | ||

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.08 (1.06–1.11) | 5 | [113] | |

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.14 (1.06–1.21) | 21 | [124] |

| Dose-Response | 1.17 (1.10–1.23) | 16 / | [124] [115] | |

| 1.18 (1.10–1.28) | 10 | [125] | ||

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | 15 | [126] |

| 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 14 | [127] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | 12 | ||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.15 (1.03–1.29) | 8 | [128] |

| 1.24 (1.04–1.47) | 10 | [129] | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.21 (1.04–1.41) | 7 | ||

| Total Meat | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 6 | [117] |

| Dose-Response | / | 6 | ||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.23 (0.98–1.49) | 7 | [131] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.18 (1.09–1.28) | 4 | [119] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 1.12 (1.01–1.24) | 8 | [122] | |

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | / | / | [90] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 13 | [128] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Poultry | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | / b | / | [115] | |

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 6 | [117] |

| Dose-Response | / | 5 | ||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | / b | / | [115] | |

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.87 (0.78–0.96) | 2 | [119] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | / b / | / 3 | [115] [122] | |

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.78 (0.62–0.94) b | / | [115] | |

| / | 6 | [125] | ||

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 11 | [127] |

| Dose-Response | / | 10 | ||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / / | 7 5 | [128] [129] |

| Dose-Response | / | 4 | [129] | |

| Health Outcomes | Unit of Intake | RR (95% C.I.) | N° of Prospective Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Fish | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.95 (0.92–0.98) | 38 | [114] |

| 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 12 | [140] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 19 / | [114] [115] | |

| 0.88 (0.83–0.93) | 5 | [140] | ||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.94 (0.88–1.02) | 22 | [118] |

| 0.81 (0.70–0.92) | 29 | [131] | ||

| 0.91 (0.84–0.97) | 22 | [141] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.88 (0.79–0.99) | 15 / | [118] [115] | |

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.95 (0.89–1.01) | 20 | [118] |

| 0.90 (0.85–0.96) | 31 | [142] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | 15 / | [118] [115] | |

| 0.94 (0.89–0.99) a | 11 | [143] | ||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 8 | [120] |

| Dose-Response | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 7 | ||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 8 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | 0.80 (0.67–0.95) | 7 | ||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | / / | 9 7 | [121] [122] |

| Dose-Response | / | / | [115] | |

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 1 | [123] |

| Dose-Response | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 1 | ||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.80 (0.66–0.96) b | 6 | [144] | |

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | / | [90] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 21 | [124] |

| 0.93 (0.86–1.01) | 22 | [145] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.93 (0.85–1.01) | 16 / | [124] [115] | |

| 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 11 | [125] | ||

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / / | 11 18 | [146] [127] |

| Dose-Response | / | 13 | [127] | |

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 10 | [128] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Oily Fish (Fat) | ||||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 5 | [147] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.89 (0.82–0.96) | 4 | [122] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Lean Fish | ||||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.81 (0.67–0.99) | 4 | [147] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 4 | [122] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Health Outcomes | Unit of Intake | RR (95% C.I.) | N° of Prospective Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Eggs | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.06 (1.00–1.12) | 8 | [114] |

| Dose-Response | 1.15 (0.99–1.34) | 5 / | [114] [115] | |

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) | 8 | [164] | |

| Total CVDs incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.94 (0.89–0.99) | 9 | [164] | |

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | / / | 6 11 | [131] [118] |

| Dose-Response | / / / / | 6 9 / 12 | [165] [118] [115] [164] | |

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 10 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | / | 10 / | [118] [115] | |

| 0.97 (0.93–1.02) | 6 | [164] | ||

| 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 6 | [165] | ||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.54 (0.32–0.91) | 1 | [120] |

| Dose-Response | 0.25 (0.08–0.74) | 1 | ||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.25 (1.12–1.39) | 4 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 4 | ||

| 1.11 (0.99–1.25) | 4 | [164] | ||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 5 | [121] |

| Dose-Response | / / | / 13 | [115] [122] | |

| 1.16 (1.09–1.23) | 13 | [166] | ||

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.35 (1.11–1.36) | 4 | [124] |

| Dose-Response | / / | 3 / | [124] [115] | |

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 9 | [127] |

| Dose-Response | / | 8 | ||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 9 | [128] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Health Outcomes | Unit of Intake | RR (95% C.I.) | N° of Prospective Studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Dairy Products | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 27 | [114] |

| / | 33 | [169] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 16 / | [114] [115] | |

| 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 20 | [169] | ||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 16 | [169] |

| Dose-Response | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 13 | ||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.91 (0.82–1.00) | 11 | [130] |

| / | 13 | [118] | ||

| Dose-Response | / | 10 / | [118] [115] | |

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.79 (0.75–0.82) | 7 | [130] |

| 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 12 | [118] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 11 / | [118] [115] | |

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.89 (0.86–0.93) | 9 | [120] |

| Dose-Response | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | 9 | ||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 3 | [118] |

| Dose-Response | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 1 | ||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.89 (0.84–0.89) | 11 | [121] |

| 0.92 (0.86–0.97) | 4 | [130] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | / 21 | [115] [122] | |

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 6 | [123] |

| Dose-Response | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 5 | ||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.75 (0.66–0.84) | 12 | [168] |

| Dose-Response | 0.91 (0.85–0.96) | 9 | ||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 19 | [169] |

| Dose-Response | / | 9 | ||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | / | [90] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.83 (0.76–0.89) | 18 | [124] |

| Dose-Response | 0.93 (0.91–0.94) | 15 / | [124] [115] | |

| 0.87 (0.83–0.90) | 10 | [125] | ||

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 16 | [170] |

| Dose-Response | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) a | / | ||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 3 | [128] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total Milk | ||||

| All-cause Mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 27 | [169] |

| Dose-Response | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 16 | ||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 15 | [169] |

| Dose-Response | / | 9 | ||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | / | 10 | [122] | |

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.78 (0.69–0.87) | 7 | [168] |

| Dose-Response | 0.87 (0.79–0.95) | 6 | ||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 13 | [169] |

| Dose-Response | 1.03 (0.99–1.06) | 8 | ||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | 9 | [125] | |

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | / | [170] |

| 0.92 (0.84–1.02) | 18 | [127] | ||

| Dose-Response | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 11 | ||

| / | / | [170] | ||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Whole milk (w) and skim milk (s) | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.15 (1.09–1.20) (W) | 9 | [169] |

| /(S) | 8 | |||

| Dose-Response | 1.10 (1.00–1.21) (W) | 6 | ||

| /(S) | 6 | |||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.09 (1.02–1.16) (W) | 5 | [169] |

| /(S) | 4 | |||

| Dose-Response | /(W) | 4 | ||

| /(S) | 4 | |||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.87 (0.78–0.96) (W) | 7 | [121] |

| No data (S) | ||||

| Dose-Response | /(W) /(S) | 9 7 | [122] | |

| Overweight/Obesity | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| MetS | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total cancer mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | 1.17 (1.08–1.28) (W) | 7 | [169] |

| /(S) | 7 | |||

| Dose-Response | 1.13 (1.01–1.28) (W) | 6 | ||

| /(S) | 6 | |||

| Total cancer incidence | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CRC | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Breast cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | /(W) | 7 9 | [170] [127] |

| 0.93 (0.84–1.02) (S) | 6 | [170] | ||

| 0.93 (0.85–1.00) (S) | 8 | [127] | ||

| Dose-Response | /(W) | 5 | ||

| 0.96 (0.92–1.00) (S) | 5 | |||

| Gastric cancer | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Yogurt | ||||

| All-cause mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Total CVDs mortality | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHD | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 5 | [171] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| Stroke | Highest vs. Lowest | / | 5 | [171] |

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| HBP | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| CHF | Highest vs. Lowest | No data | ||

| Dose-Response | No data | |||

| T2D | Highest vs. Lowest | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 7 | [121] |