Assessment of Nutritional Quality of Products Sold in University Vending Machines According to the Front-of-Pack (FoP) Guide

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Variables

2.2. Grouping of Food and Beverage Items

2.3. Nutritional Profiling

2.4. Statistical Analysis

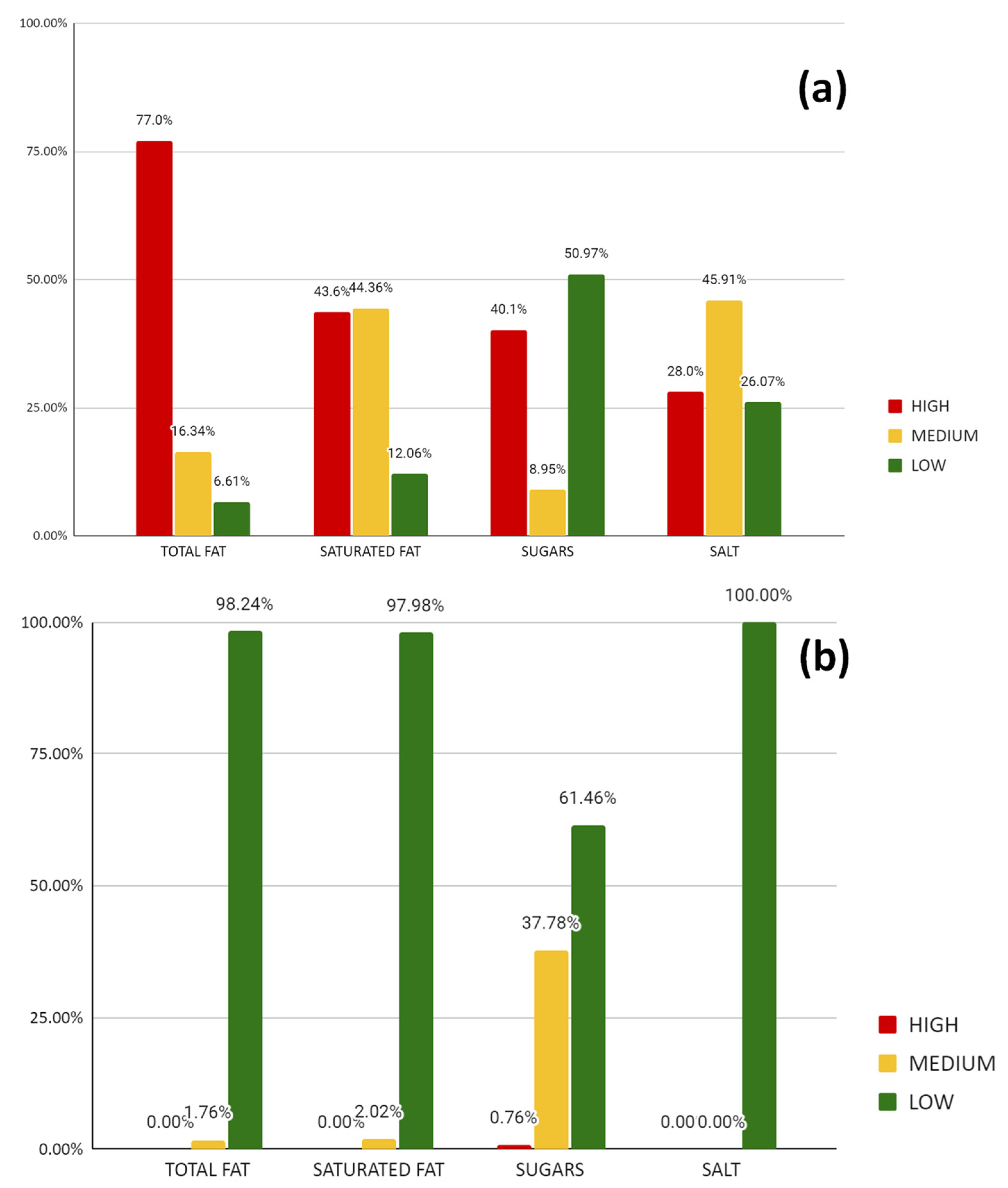

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bryce-Moncloa, A.; Alegría-Valdivia, E.; San Martin-San Martin, M.G. Obesidad y riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular. An. Fac. Med. 2017, 78, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cuixart, C.B.; Bejarano, J.M.L. Nuevas guías europeas de prevención cardiovascula y su adaptación española. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Informe Anual del Sistema Nacional de Salud (SNS). Resumen Ejecutivo. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. 2018. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/sisInfSanSNS/tablasEstadisticas/InfAnualSNS2018/ResumenEjecutivo2018.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Pasch, K.E.; Lytle, L.A.; Samuelson, A.C.; Farbakhsh, K.; Kubik, M.Y.; Patnode, C.D. Are school vending machines loaded with calories and fat: An assessment of 106 middle and high schools. J. Sch. Health 2011, 81, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Papadaki, A. Nutritional value of foods sold in vending machines in a UK University: Formative, cross-sectional research to inform an environmental intervention. Appetite 2016, 96, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.; Sánchez, C.; Suarez, M.; García, R.; Blanco, M.; Álvarez, F. Composición nutricional de los alimentos de las vending de edificios públicos y hospitalarios de Asturias. Aten. Prim. 2018, 52, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raposo, A.; Carrascosa, C.; Pérez, E.; Tavares, A.; Sanjuán, E.; Saavedra, P.; Millán, R. Vending machine foods: Evaluation of nutritional composition. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2016, 28, 448–463. [Google Scholar]

- Grech, A.; Hebden, L.; Roy, R.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Are products sold in university vending machines nutritionally poor? A food environment audit. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asociación Nacional Española de Distribuidores Automáticos. Informe 2018. El Usuario de Máquinas Vending. Aneda Vending Website. Available online: https://aneda.org/estudio-de-mercado (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Department of Health, Food Standards Agency, and Devolved Administrations in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales. Guide to Creating a Front of Pack (FoP) Nutrition Label for Pre-Packed Products Sold through Retail Outlets. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/566251/FoP_Nutrition_labelling_UK_guidance.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Kelly, B.; Flood, V.M.; Bicego, C.; Yeatman, H. Derailing healthy choices: An audit of vending machines at train stations in NSW. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2012, 23, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Johnson, M.; Quick, V.M.; Walsh, J.; Greene, G.W.; Hoerr, S.; Colby, S.M.; Kattelmann, K.K.; Phillips, B.W.; Kidd, T.; et al. Sweet and salty. An assessment of the snacks and beverages sold in vending machines on US post-secondary institution campuses. Appetite 2012, 58, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Boyle, M.; Craypo, L.; Samuels, S. The food and beverage vending environment in health care facilities participating in the healthy eating, active communities program. Pediatrics 2009, 123 (Suppl. S5), S287–S292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spronk, I.; Kullen, C.; Burdon, C.; O’Connor, H. Relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E.T.; Zoellner, J.M. Nutrition and health literacy: A systematic review to inform nutrition research and practice. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.W.; Sangster, J.; Priestly, J. Assessing the availability, price, nutritional value and consumer views about foods and beverages from vending machines across university campuses in regional New South Wales, Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.I.; Jarrar, A.H.; Abo-El-Enen, M.; Al Shamsi, M.; Al Ashqar, H. Students’ perspectives on promoting healthful food choices from campus vending machines: A qualitative interview study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, R.; Yassa, B.; Parker, H.; O’Connor, H.; Allman-Farinelli, M. University students’ on-campus food purchasing behaviors, preferences, and opinions on food availability. Nutrition 2017, 37, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Soo, D.; Conroy, D.; Wall, C.R.; Swinburn, B. Exploring University Food Environment and On-Campus Food Purchasing Behaviors, Preferences, and Opinions. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Genova, L.; Cerquiglini, L.; Penta, L.; Biscarini, A.; Esposito, S. Pediatric Age Palm Oil Consumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.R.; Maarof, S.K.; Ali, S.S.; Ali, A. Systematic review of palm oil consumption and the risk of cardiovascular disease. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl, B.; Sanders, D.S.; Green, P.H.R. Coeliac disease. Lancet 2018, 391, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epuru, S.; Al Shammary, M. Nutrition knowledge and its impact on food choices among students of Saudi Arabia. IOSR-JDMS 2014, 12, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines: Providing the scientific evidence for healthier Australian diets. National Health and Medical Research Council website. Available online: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/adg (accessed on 28 October 2022).

- Robles, B.; Wood, M.; Kimmons, J.; Kuo, T. Comparison of nutrition standards and other recommended procurement practices for improving institutional food offerings in Los Angeles County, 2010–2012. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocken, P.L.; van Kesteren, N.M.; Buijs, G.; Snel, J.; Dusseldorp, E. Students’ beliefs and behaviour regarding low-calorie beverages, sweets or snacks: Are they affected by lessons on healthy food and by changes to school vending machines? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1545–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gorton, D.; Carter, J.; Cvjetan, B.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Healthier vending machines in workplaces: Both possible and effective. N. Z. Med. J. 2010, 123, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Nutrition Service, USDA. National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: Nutrition standards for all foods sold in school as required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. Interim final rule. Fed. Regist. 2013, 78, 39067–39120. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Perez, N.; Arroyo-Izaga, M. Availability, Nutritional Profile and Processing Level of Food Products Sold in Vending Machines in a Spanish Public University. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharis, M.L.; Colby, L.; Wagner, A.; Mallya, G. Sales of healthy snacks and beverages following the implementation of healthy vending standards in City of Philadelphia vending machines. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grech, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. A systematic literature review of nutrition interventions in vending machines that encourage consumers to make healthier choices. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 1030–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.M.; Moltó, J.C.; Mañes, J. Dietary intake and food pattern among university students. Nutr. Res. 2000, 20, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reus Project: Program for the Promotion of Health in University Environments. Available online: https://www.restauracioncolectiva.com/n/proyecto-reus-un-programa-por-la-promocion-de-la-salud-en-los-entornos-universitarios (accessed on 28 October 2022).

| Text | Low | Medium | High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour Code | Green | Amber | Red | |

| For food | ||||

| >25% of RIs | >30% of RIs | |||

| Fat | ≤3.0 g/100 g | >3.0 g to ≤17.5 g/100 g | >17.5 g/100 g | >21 g/portion 1 |

| Saturates | ≤1.5 g/100 g | >1.5 g to ≤5.0 g/100 g | >5.0 g/100 g | >6.0 g/portion 1 |

| (Total) Sugars | ≤5.0 g/100 g | >5.0 g to ≤22.5 g/100 g | >22.5 g/100 g | >27 g/portion 1 |

| Salt | ≤0.3 g/100 g | >0.3 g to ≤1.5 g/100 g | >1.5 g/100 g | >1.8 g/portion 1 |

| For drinks | ||||

| >12.5% of RIs | >15% of RIs | |||

| Fat | ≤1.5 g/100 mL | >1.5 g to ≤8.75 g/100 mL | >8.75 g/100 mL | >10.5 g/portion 2 |

| Saturates | ≤0.75 g/100 mL | >0.75 g to ≤2.5 g/100 mL | >2.5 g/100 mL | >3 g/portion 2 |

| (Total) Sugars | ≤2.5 g/100 mL | >2.5 g to ≤11.25 g/100 mL | >11.25 g/100 mL | >13.5 g/portion 2 |

| Salt | ≤0.3 g/100 mL | >0.3 g to ≤0.75 g/100 mL | >0.75 g/100 mL | >0.9 g/portion 2 |

| Humanities | Health Sciences | Campus Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biscuits | 4.3% | 2.4% | 3,1% | 0.158 |

| Breadsticks | 8.3% | 8.5% | 8.4% | 0.919 |

| Candies and sweets | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.9% | 0.105 |

| Chewing gums | 2.2% | 1.7% | 1.8% | 0.634 |

| Chocolates and bars | 12.6% | 9.4% | 10.6% | 0.207 |

| Energy drinks | 4.3% | 0.9% | 2.1% | 0.004 * |

| Fruit | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 1 |

| Juices | 3.9% | 5.0% | 4.6% | 0.544 |

| Milkshakes | 3.0% | 2.8% | 2.9% | 0.877 |

| Nuts | 3.0% | 2.1% | 2.4% | 0.467 |

| Pastries | 2.6% | 3.5% | 3.2% | 0.520 |

| Potato chips | 2.2% | 1.9% | 2.0% | 0.802 |

| Sandwich | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.9% | 0.070 |

| Snacks | 5.7% | 6.1% | 6.0% | 0.805 |

| Soft drinks | 16.1% | 27.4% | 23.4% | 0.001 * |

| Water | 30.0% | 26.4% | 27.7% | 0.328 |

| Energy (Kcal) | Fats (g/100 g/mL) | SFA (g/100 g/mL) | CH (g/100 g/mL) | Sugars (g/100 g/mL) | Fibra (g/100 g/mL) | Protein (g/100 g/mL) | Salt (g/100 g/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biscuits | 471.7 ± 45.4 | 22.0 ± 4.6 | 8.5 ± 6.6 | 62.5 ± 3.2 | 23.2 ± 19.7 | 5.3 ± 3.3 | 7.7 ± 1.4 | 1.4 ± 1.6 |

| Breadsticks | 500.9 ± 17.4 | 25.5 ± 4.3 | 3.5 ± 2.1 | 56.6 ± 5.7 | 2.5 ± 2.8 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

| Candies and sweets | 368.0 ± 24.0 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 86.7 ± 6.4 | 56.7 ± 20.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| Chewing gum | 155.0 ± 9.1 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 64.1 ± 2.8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Chocolates and bars | 515.2 ± 50.6 | 28.1 ± 9.5 | 16.3 ± 5.9 | 57.5 ± 10.9 | 42.8 ± 9.9 | 2.7 ± 3.3 | 7.0 ± 1.3 | 0.7 ± 1.3 |

| Nuts | 566.2 ± 59.1 | 43.1 ± 12.3 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 21.9 ± 19.9 | 7.4 ± 6.8 | 7.0 ± 3.6 | 20.1 ± 6.8 | 0.9 ± 0.8 |

| Pastries | 454.5 ± 45.2 | 23.8 ± 5.2 | 14.8 ± 4.4 | 54.7 ± 3.1 | 30.6 ± 6.6 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Potato chips | 540.8 ± 16.2 | 34.2 ± 3.3 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 49.9 ± 4.4 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 0.6 |

| Sandwich | 256.0 ± 18.7 | 12.5 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 1.4 | 26.5 ± 3.4 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | 1.6 ± 0.3 |

| Snacks | 484.7 ± 29.2 | 21.7 ± 4.5 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 64.5 ± 3.9 | 3.2 ± 2.1 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.6 |

| Energy drinks | 42.0 ± 13.8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 10.1 ± 3.3 | 9.8 ± 3.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| Juices | 21.3 ± 15.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 4.6 ± 3.7 | 4.2 ± 3.2 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Milkshakes | 62.8 ± 15.6 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 8.8 ± 3.0 | 8.5 ± 2.9 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| Soft drinks | 19.1 ± 14.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 4.6 ± 3.7 | 4.6 ± 3.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Water | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.00 ± 0.0 |

| Key Recommendations to Reduce Risk of Chronic Disease (NAIRCD) | |

|---|---|

| Fat and saturated fat | Reduce food categories high in fat and saturated fat such as chocolates, pastries, snacks and potato chips. Consider reducing breadsticks and biscuits if their profile is not improved. |

| Promote food groups that are low in fat and especially low in saturated fat such as fruits, salads and sandwiches. Consider the promotion of natural nuts as a source of healthy fats. | |

| Sugars | Reduce sugar-rich food items such as chocolates, pastries and sweets. |

| Promote food categories with moderate to low sugar content such as nuts, sandwiches and breadsticks if their profile is improved. | |

| Promote water and beverages with “low sugar” and “0% added sugar” claims. | |

| Salt | Reduce categories with high or moderate salt that would be mainly: breadsticks, biscuits, snacks and sandwiches, given their profile was not improved. |

| Promotion of the food categories with low salt content: nuts (without added salt) and fresh fruit. | |

| Food items | Reduce fried salty nuts and introduce natural or roasted nuts without added salt. Some nuts with this profile are already present in the VMs. |

| Substitute chocolates and bars for whole grain bars with seeds or dried fruits, preferably low low-moderate in saturated fat. | |

| Reduce potato chips preferably. Preference for chips fried in olive oil since it contains healthy monounsaturated fats. | |

| Promote snacks moderate in fat (mainly with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats), moderate–low in saturated fat, low in sugar and preferably moderate–low in salt. No snacks were currently offered with this nutritional profile. | |

| Introduce fresh fruits: they have high nutritional value due to their contribution of vitamins and minerals. Some high in fiber also provide satiety, which makes them an ideal snack. | |

| Although biscuits are not advisable, it is preferable to select wholegrain biscuits with moderate-low content of saturated fat, sugar and salt. | |

| Introduce wholegrain sandwiches and breadsticks moderate-low in salt, preferably with high proportions of nuts and seeds. | |

| Beverages | Promote water over all other beverages. At least 60% of the drinks should be water. |

| Reduce soft drinks. Choose sugar-free or low in sugar options. | |

| Promote milkshakes and juices with a higher percentage of milk, fruits and vegetables in their ingredients. | |

| Reduce energy drinks and choose those low in sugar. | |

| Introduce categories such as milk or yogurts with fruits and without added sugars. | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lasala, C.; Durán, A.; Lledó, D.; Soriano, J.M. Assessment of Nutritional Quality of Products Sold in University Vending Machines According to the Front-of-Pack (FoP) Guide. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5010. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235010

Lasala C, Durán A, Lledó D, Soriano JM. Assessment of Nutritional Quality of Products Sold in University Vending Machines According to the Front-of-Pack (FoP) Guide. Nutrients. 2022; 14(23):5010. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235010

Chicago/Turabian StyleLasala, Carmen, Antonio Durán, Daniel Lledó, and Jose M. Soriano. 2022. "Assessment of Nutritional Quality of Products Sold in University Vending Machines According to the Front-of-Pack (FoP) Guide" Nutrients 14, no. 23: 5010. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235010

APA StyleLasala, C., Durán, A., Lledó, D., & Soriano, J. M. (2022). Assessment of Nutritional Quality of Products Sold in University Vending Machines According to the Front-of-Pack (FoP) Guide. Nutrients, 14(23), 5010. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235010